Latest reviews

As of this writing, James C. Scott is 81 years old. Best known for Seeing Like a State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed (reviews), he is an accomplished scholar of non-state societies. Near the end of his career, Scott is not pulling any punches. Against the Grain seeks to dismantle the standard civilizational narrative — that early state-based agricultural societies were part of a linear progression towards civilization as we understand it today.

Scott demonstrates that the hunter-gatherer lifestyle that preceded sedentary agriculture was egalitarian, relatively peaceful, and allowed for significant leisure time, and that early human cultures combined a variety of approaches to survive. Beyond hunting and gathering, these included shifting agriculture, pastoralism (raising livestock and moving the herd in search of new pastures), and even sedentary agriculture, well before the emergence of states.

Our ancestors were opportunistic and looked for the quickest way to make a living. Agriculture wasn’t necessarily a response to population pressure — depending on the environment, it just offered a more reliable return than hunting and gathering.

In Scott’s narrative, the creation of what he calls “late-Neolithic multi-species resettlement camps” — settlements where humans, livestock, other domesticated animals like dogs, and domesticated plants lived together for extended periods of time — caused never before seen levels of drudgery and misery. The high population concentration led to disease and crop failures, and agricultural cultivation created tedium and reduced cultural complexity.

But it also created opportunities for those who accumulated power to attempt to preserve it. The settlements could be strengthened by abducting and enslaving nomads or members of other communities. By standardizing on cereal grains — “visible, divisible, assessable, storable, transportable, and ‘rationable’” — early states were able to sustain their bureaucracies (and increase elite wealth) through taxation.

A polemic against civilization

War and slavery were not inventions of the state, Scott acknowledges, but it is only through the concentrated power of early states that they could they be brought to a previously unseen scale. When state societies collapsed, many of the enslaved or coerced members (if they survived—a big “if” Scott glosses over a bit too readily) were better off. And state collapse occurred frequently, due to disease, war, starvation, rebellion, and other causes.

Meanwhile, the “barbarians” who did not join state-based societies (and who could not easily be captured because of where they lived) became more sophisticated, extracting tribute from the state — but also selling each other out to serve as mercenaries for hire.

Where Scott’s writing turns into polemic is when he dismisses the idea of “dark ages” (such as the Greek Dark Age or, though he barely writes about it, the period following the collapse of the Roman Empire). The fact that we don’t find monumental buildings, wall paintings, or a strong written tradition, he reminds us, doesn’t mean nothing of interest happened — after all (a point Scott repeats), Homer’s great epic was composed during a “dark age” and transmitted orally.

Scott persuasively marshals the evidence that concentration caused many new hardships, and led to societies which were frequently (if not always) deeply unjust. But he does not attempt to examine the arguments against dispersal, or for large numbers of humans living with each other in close proximity, sharing ideas and beliefs at a pace previously unimagined.

He dismisses “elite displays” such as monuments and temples, but does not write about roads, aqueducts, libraries, poverty relief such as the Cura Annonae, or any legitimate effort to better the life of a community’s members, if such life was organized partially through a state.

Indeed, the word “science” does not appear in the book’s index. Human progression that is the result of better understanding our world and applying that knowledge is too readily dismissed in an effort to keep the book true to its title.

Here, Scott’s book — so critical of ideological views of “civilization” — is itself ideologically committed to rejecting an evidence-based view. “But what of the slaves?” one can imagine Scott saying. “But what of the elites, enriching themselves?” Yes, but what of Euclid, Democritus, Ovid? What of the Library of Alexandria, or the Antikythera mechanism, or the art of Pompeii? What of the religious extremism that followed Rome’s collapse, and probably followed earlier collapses as well?

The verdict

Scott uses language not to obfuscate, but occasionally in ways I would describe as performative. Against the Grain makes frequent use of technical terms from agriculture and anthropology; the writing is dry (though suffused with a dark academic humor) and sometimes repetitive. What keeps the book interesting is its challenge to orthodoxies and its willingness to put things plainly when required, e.g., when writing about slavery.

Against the Grain does re-cast our understanding of history. Scott is correct to critique those who want to see linear progression in human history; a rise from savagery. Deep history that looks at the distant past of our species is crucial to get a clear picture of how we became who we are. Our hunter-gatherer ancestors were far from stupid, and their minds were far from simplistic compared to our own, nor were their lives especially brutal or difficult.

History cannot be understood without examining the accumulation of power and resources, all too often including slaves and other coerced labor. If we want to build morally just societies, we must understand how this accumulation of power is at odds with moral progress, even as it has often enabled scientific or technological progress.

But here ends the usefulness of Scott’s book. The fact that his work celebrates the dispersed life beyond the reach of the state is perhaps precisely why his colleagues can celebrate him as an anarchist academic. His writing poses no threat to real systems of power, because it offers no alternative. It is an important read, but only as a starting point for developing a more nuanced understanding of the human story, correcting misconceptions in the common narrative still taught in schools. In the final analysis, Scott is a rebel without a cause.

Slic3r is an open source slicing program with the features you’d expect. The Prusa edition adds in some integration with Prusa printers to make program setup a bit easier.

UI

UI is pretty and works well for common tasks. There are some menus and advanced features that are inscrutable until you go through the documentation. You have to manually keep track of which tab you are in. Parts only show up in 3D and 2D tabs until they have been sliced, then you can see more in preview and layers tabs. Settings are nicely laid out across 3 tabs at the top.

Slicing

Everything works quickly and as expected.

Verdict

Good piece of software made better with printer integration. Easy things are easy and hard things are possible(once you read the docs).

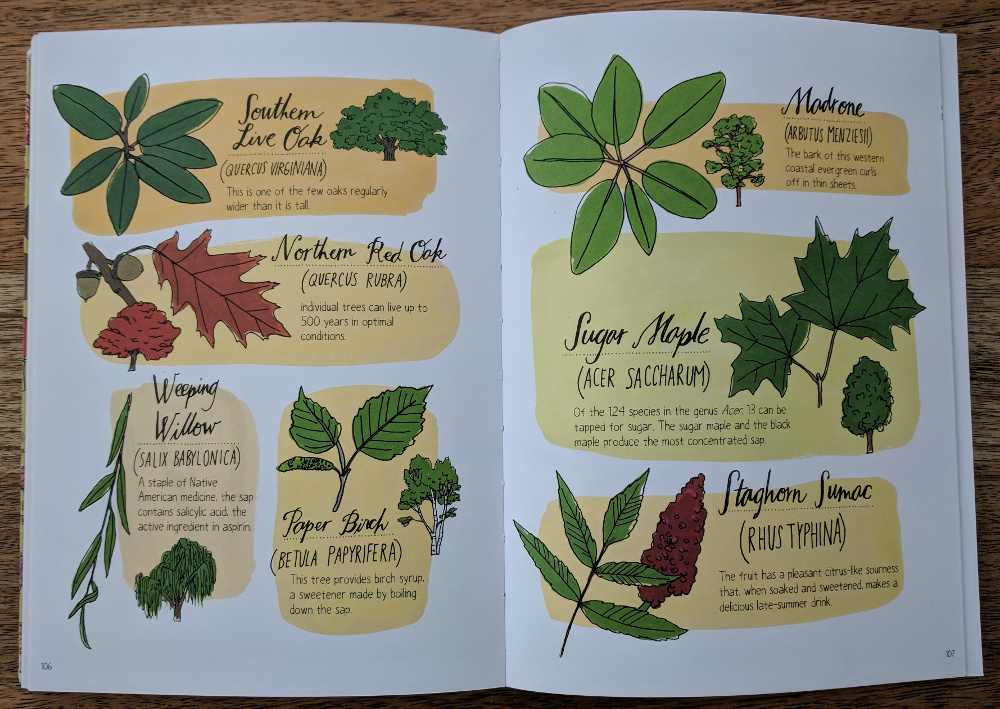

Julia Rothman is an illustrator from New York; in Nature Anatomy: The Curious Parts & Pieces of the Natural World she expresses her love of nature through 223 pages filled with colorful sketches, brief explanations and descriptions.

The art is simple but elegant, conveying the most recognizable characteristics of a leaf, a mushroom or a butterfly in just a few strokes. The organization varies from page to page:

-

annotated illustrations (“anatomy of a flower”) with brief explanations;

-

illustrations without any text or explanation other than a species name;

-

illustrations with brief facts about a species (“Woodchuck: Woodchucks can climb trees if they need to escape”)

-

recipes and other offbeat material, e.g., instructions for printing plant patterns.

This kind of presentation is fairly typical for the book: elegant illustrations accompanied by one or two facts. (Credit: Julia Rothman. Fair use.)

Of course, the book can only sample the natural world (and it does so with a North American bias), but it does attempt to provide some broader explanations as well, e.g., about moon phases or the layers of Earth’s atmosphere.

Some of the text is in cursive, giving the book the feel of an intimate journal. That’s clearly the idea: making the complexity of nature less intimidating by focusing on its beauty and by conveying descriptions and explanations in a casual manner.

At the same time, this approach can no more than whet the appetite for more detailed explanations why nature is the way it is (for which speaking about evolution, which this book hardly does, is essential).

Is this approach suitable for getting young people excited about the natural world? I’m no longer a young reader, but if I was, I bet I would have been in equal parts frustrated and pulled in by this book; pulled in by its art, and frustrated by its failure to go beyond enumerating names and facts. I would give the book 5 stars for art and 3 stars for the text—a good purchase for extending one’s appreciation of the patterns of nature, if not necessarily for understanding them.

With tough, knobbly bark and branches spaced closely but not too closely, this tree invites you to gently ascend to it’s sturdy mid-trunk branches to take in the view and be embraced by lightly-scented twigs.

The Lion’s Song is an episodic cross-platform video game set in and near Vienna shortly before the First World War. The game features pixel art in a six color sepia palette, which gives it a unique look and feel.

While the game mechanics resemble point-and-click adventure games, this is more of an interactive story. There is no inventory; choices and decisions largely take the place of puzzles.

Each of the four episodes only has about 30 minutes of play time, but the game encourages you to revisit past decisions and explore the connections between the lead characters of each episode (all fictional):

-

Wilma Dörfl, a composer of humble origins who is trying to finish a pivotal piece that could make or break her career, while figuring out her relationship with her mentor;

-

Franz Markert, a painter who is making his debut in Gustav Klimt’s art salon, and who can see “layers” in the personalities of the people around him, while being unable to see them in himself;

-

Emma Recniczek, a mathematician who is looking for guidance from Vienna’s “Radius” (a circle of mathematicians who meet regularly in the backroom of a cafe), but who faces rejection because she is a woman;

-

Albert, the son of a baron who wanted to become a journalist, but finds himself forced to start a military career; during a train journey he meets people who are connected to each of the three characters above.

Franz Markert (second from left) in the art salon (Credit: Mipumi Games GmbH. Fair use.)

The second and third episode have the most depth. It’s fun to be Markert and visit Vienna’s street vendors or the art salon, observing little ghost figures (the “layers” he sees in people’s personalities) appear behind other characters as you walk by them. You get to choose which character you want to paint, which contributes a lot to the replay value of this episode.

Playing Emma, you face important choices regarding your identity and how you present yourself to others, as you try to overcome the societal obstacles to your career as a female mathematician developing a new “theory of change”. Along the way, you briefly meet Markert in a cafe, who is always on the lookout for interesting people to paint.

The sounds and music of the game—the storm and rain outside Wilma’s cabin; the sound of horses in the streets of Vienna; the chatter of the salon—give the game an immersive quality that you might not expect from looking at its low-resolution graphics. The composition which gives the game its title—the Lion’s Song which Wilma composes in the first episode—plays a role similar to the Cloud Atlas composition in David Mitchell’s book of the same name, connecting the threads of story through a tapestry of beautiful music.

Some elements of the story are a bit forced (the confrontation between mathematicians in front of a class of unruly students comes to mind), but for the most part, you become invested in the characters and their fates. The decisions you make truly do have ripple effects throughout the episodes, from the exact composition of the music to the paintings that appear on the walls and the epilogue of the game. Even marginal aspects of the game—credits screens, the “connections” section—are lovingly designed interactive rooms.

You’re unlikely to get more than an evening or two of enjoyment out of this brief game, but the gorgeous art and music, the attention to detail, and the fascinating setting and characters make it unlikely that anyone who enjoys interactive stories would regret this purchase (as of this writing, $10 at GOG).

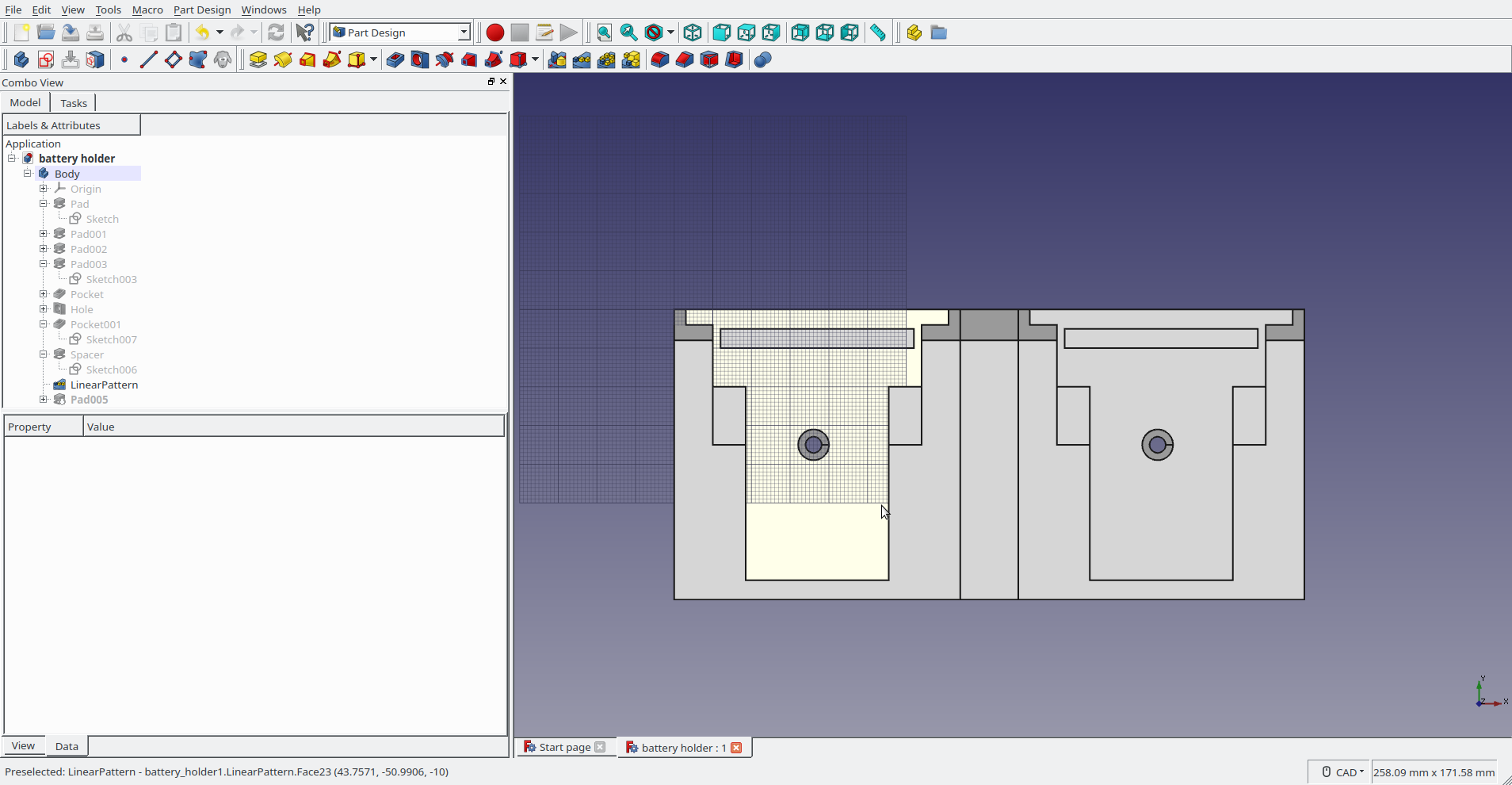

FreeCAD is a FOSS 3D parametric modeler that runs on Linux, Mac and Windows. This is a review of version 0.17.

Features

Parametric modeling

Parametric modeling is the killer feature here. It allows you to link dimensions so they autoupdate when the parent changes. This is early software and it shows. Sketches mapped to faces will map themselves to a different plane when editing a feature above the sketch in the feature tree. You can also link dimensions by naming a dimension and then referencing it by name when creating another constraint: Sketch.constraints.name. This part is well thought out and easy to use. Datum features are new in this version and need work. I’ve spent several hours fighting to get the datum planes defined correctly even when doing simple things like creating a copy of the xy plane but higher on the z axis. That being said, once a part is modeled with datum planes and dimensions are controlled with named constraints, everything works well.

Sketcher

Sketcher is on par with commercial programs for the most part. I’ve had issues with auto constraints not always being applied which will cause issues when you try to base a feature on the sketch. The solver has issues that will lead you to overconstrain sketches if you follow its guidance. Fixes for this are already in the 0.18 branch.

UI

Straight forward and relatively easy to use. It’s interface is similar to many other CAD programs with toolbars for commands and a feature tree for the part. The property view panel is a great addition that allows you to see all the properties of feature or sketch and edit them. The UI is confusing when multiple parts are open in seperate tabs because the feature tree keeps both parts in the same pane and doesn’t change focus when you switch tabs. This leads to many unintended edits on the part you can no longer see.

FreeCAD 0.17 (Own work. License: CC-BY-SA.)

Verdict

Software is usable now with quirks that come with early development software. The majority of features of a true 3D parametric modeler seem to be in the program but many need work. Assemblies are not yet implemented… The ongoing development should make this software not only usable but competitive with commercial products in a few years.

Assembly

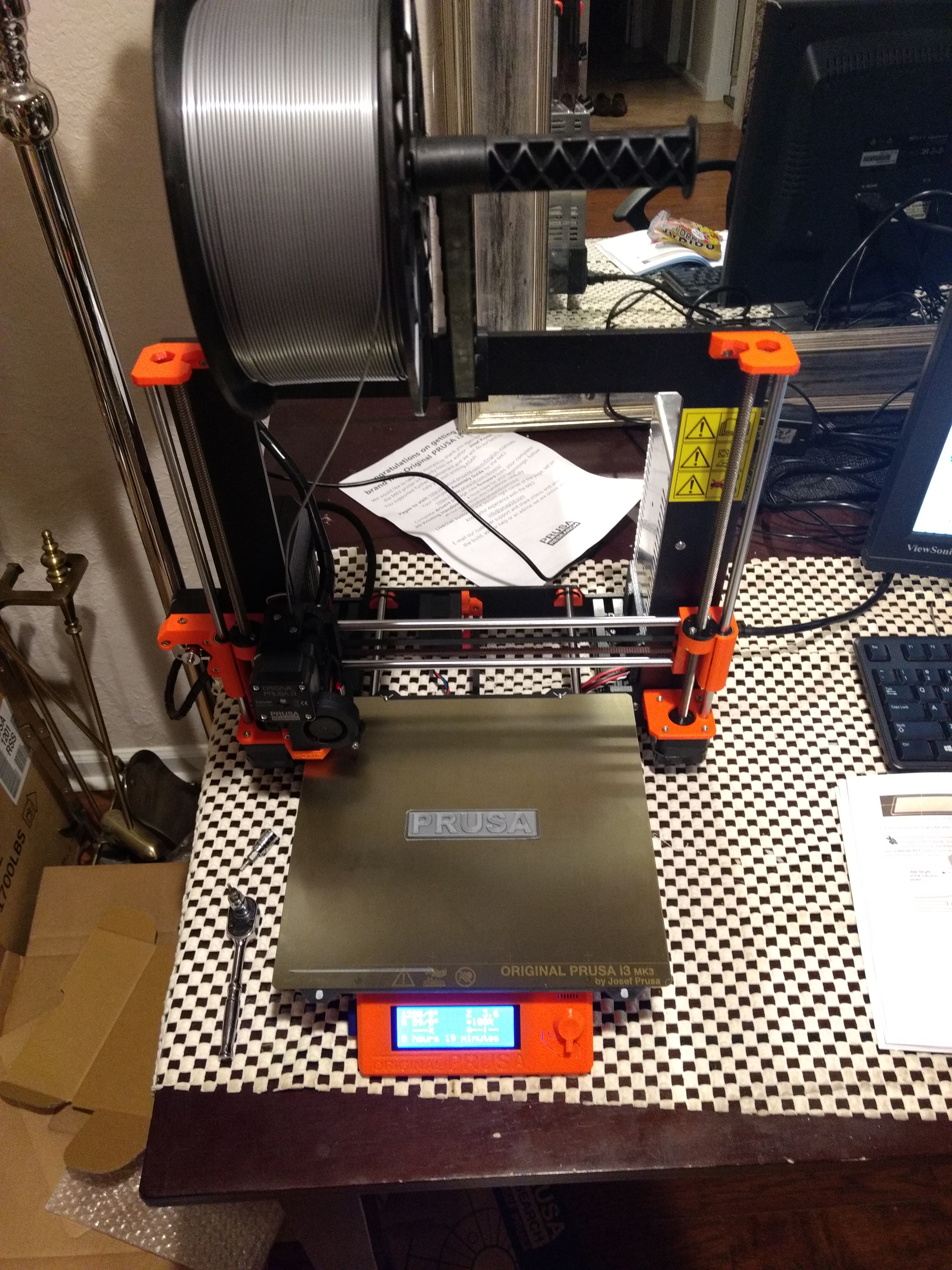

i3 mk3 kit (Own work. License: CC-BY-SA.)

Kit arrives in box with several smaller boxes inside for the sub assemblies. Everything is well organized and labeled. The kit comes with tools for assembly, 1 kg of PLA and gummy bears. Assembly of the kit took around 12 hours and can be tedious. Be prepared to spend much more time than that if you aren’t experienced with this kind of work. Assembly instructions were generally good but, use the online version so you can see comments where people had trouble or the instructions were confusing. The tuning once the printer was assembled takes patience and is a bit unsettling. It has you do a pre-programmed print and adjust the z axis down while printing to calibrate extruder to print bed relation.

The belt tightening on the x axis is bad. Pull as hard as you can or you’ll find the belt is too loose even with the tension adjust and have to take the back off the x carriage again. Be careful, the tension adjustment will crack the mount with no notice! Also, high belt numbers mean loose belt, low numbers mean tight belt so if you’re above 280 go back and tighten your belts.

Assembled i3 mk3 (Own work. License: CC-BY-SA.)

Software

I use Slic3r Prusa edition to create gcode for the machine. The integration is very well done with the defaults for the printer being loaded in automatically. Default settings have been turning out quality prints. PrintRun(pronterface) had no issue connecting to the machine and running prints.

Printing

PLA

Printing parts in pla on the default 0.2mm fast profile with 20% to 80% infill. First layer is consistently good without a brim or raft. Some features have had small issues on the first layer where there’s sharp corners or tight radii, but they rarely cause issues with the overall print. Prints pop off the PEI sheet easily and if you have trouble the entire sheet can be removed and bent.

PETG

The first spool of prints went well with default 0.2mm fast profile and 20 to 50% infill. Consistently good first layer without adjusting live z from PLA setting. Bed adhesion is good if bed is clean, dust or oil from your finger will mess up the first layer. Print will pop off with a bend of the sheet when cold. Stringing is there but easily pulled off. The next 2 spools have not printed well, but I narrowed that down to bad material.

Material since then has been printing fairly well assuming live z is set well and nozzle is clean.

Updates

The printed printer parts, software and firmware are all getting continuous updates from Prusa Research. This made me confident the machine will be well supported throughout its useful life. After a few months of ownership, it’s clear that the updates can often be beta quality with new features being disabled in the next up date, then reenabled a few updates later.

Smart Features

The filament sensor has been OK. It came disabled by default which was suprising and caused me to lose a print. It worked fine to autoload filament the few times I used it. Currently, it isn’t being recoginized by firmware. The crash detect feature has been a dissapointment as well. I have never had it recover from a crash without a layer shift of at least 0.6mm. Power panic has been tested once and failed to recover from a ~3 second power loss when the power strip was accidentally switched off. PINDA probe came with temperature compensation switched off. This means mesh bed leveling will not be correct if PINDA is hot(typically 35 C or higher). Go to Settings>Temp Cal to turn on. Then run temp calibration to set the temp compensation. You may want to manually set it using manual temp calibration since the automatic calibration isn’t very good.

Long Term Update

After a couple months with the printer, issues are starting to come up.

Bed

The steel sheet will develop bubbles underneath the PEI from prints. The bubbles have been deemed normal by Prusa Research and tend to come and go. They will not go away if you print the same part in the same spot meaning you can’t print the same parts without moving them around the bed. PEI is likely to get damaged over time if printing PETG. A well adhered print ripped off a piece of PEI after 3ish months.

Bed is now up to .25mm out of level with no mechanical adjustment available.

Power Supply

Power supply died after approximately 3 months with approximately 1 month inside enclosure. This was indicated by the input fuse blowing loudly.

PINDA

The bed leveling/ first layer issues I had were partially created due to faulty PINDA probe(outside of its lack of temperature compensation). After replacing the probe with a BLTOUCH, its clear the probe was defective and part the issues I was having.

Z Axis Sync

After getting my printer working again with the BLTOUCH, the Z axis is losing sync. I tracked the issue to a failed lead screw nut.

Verdict

Decent machine that can produce good prints until the hardware breaks down. This printer packs a lot of features in for the price but the company is not doing a good job of integrating new features and the hardware is unlikely to last. It’s clear Prusa Research relies heavily on feedback from the community to test products so you should avoid buying new models until community has had time to point out flaws and the company has time to reintegrate those changes.

Printrun is print control software that allows printer control from a connected computer. I’m reviewing based on my experience on linux.

Installation

The instructions were mediocre and somewhat misleading for Debian stable and Debian Testing. For Debian stable I had to install python3-dev and had to upgrade the wheel package using pip in addition to following the provided instructions. Debian testing instruction were good once I figured out the that proper instruction for testing were 2 sections below the standard installation section.

GUI

The UI shows you everything need but is ugly and a bit awkward to use. The underlying software seems to be solid though as it imported gcode from prusa slic3r that repetier was misinterpreting.

There is the option to setup macros that are mapped to custom buttons along with the ability to work with the console which should give many options for automating tasks.

Untested

-

pronsole(CLI for printrun)

-

printcore(library for controlling all printrun actions using python)

Verdict

Solid software that needs a lot of polishing in the GUI and installation. If you want a pretty GUI there are better options. This will likely become my go to program since it has powerful scripting capability.

Ĵus finiĝis la 74-a Internacia Junulara Kongreso, kaj ŝajnas, ke ĉiuj partoprenantoj bedaŭras, ke ĝi ne pli longe daŭris. Estis bonega etoso kun multaj jamaj kaj novaj amikoj, kaj diversaj tre interesaj programeroj.

Pri la loko:

Badajoz estas iom malfacile atingebla, sed la retpaĝo bone informis pri la vojaĝebloj. Almenaŭ estis proksime bushaltejo kaj granda vendejaro. La kongresejo estis sufiĉe granda por ne senti sin premita, sed ĉiuj ĉiam sin renkonti en la centra lokoj ĉirkaŭ la trinkejo. La ĝardeno kaj la naĝejo estis grandaj plusoj.

Pri la organizado:

La akceptejo bone funkciis, manĝoj okazis ĝustatempe, programeroj ofte iom malfruis, sed ne tro. Mi lasis mian ŝlosilon en la ĉambro unufoje, kaj ne estis problemo akiri helpon de la loka ne-esperantista teamo. Ilia nekono de Esperanto estis nur apenaŭ rimarkebla ĝeno. Mankis klare legebla programtabulo.

Pri la vespera programo:

Estis bonaj koncertoj kaj bona variado. Iom mankis danciga muziko, sed tion kompensis la diskejo. Kiam finfine post kelkaj tagoj funkciis diskejo, ĉiu nokto estis bona nokto. Mi tro malmulte vizitis la gufujon por pritaksi ĝin.

Pri taga programo:

Mi ne multe spertis la tagan programon pro komitatkunsidoj. Mi tamen ne aŭdis multajn plendojn, krom la kutimaj malfruoj, kaj unu seksisma prelego de Granda Filozofo.

Fine mi volas doni specialan laŭdon al la ĉeforganizanto Carlos Pesquera, kiu sole faris amason da laboro kaj inspiradis la reston de la teamo.

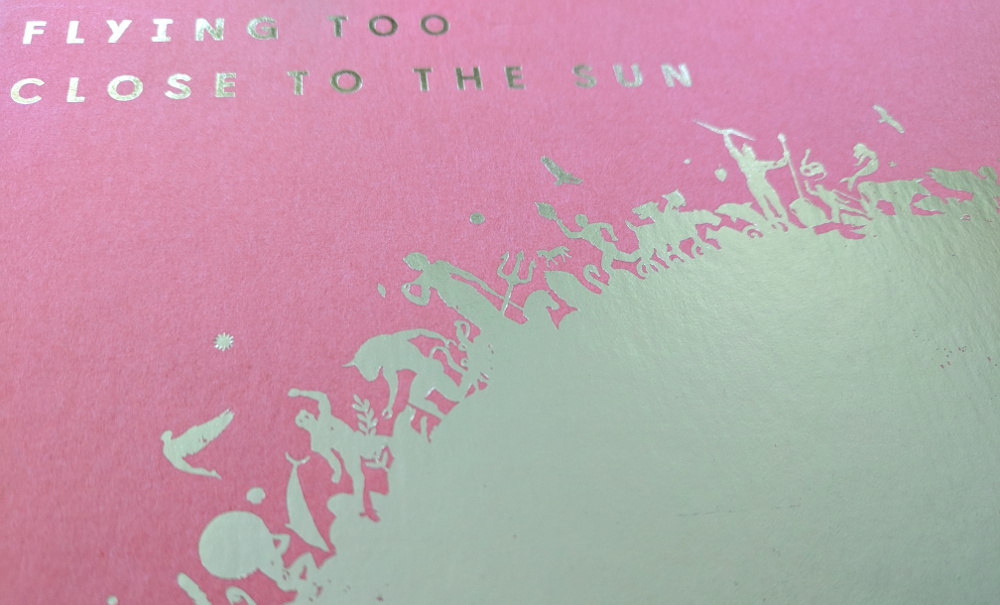

Flying Too Close to the Sun is a large format art-book from Phaidon that examines the influence of classical (Greco-Roman) myths on artistic expression since ancient Greece, for example:

-

the story of Daedalus and Icarus, which inspired the book’s title;

-

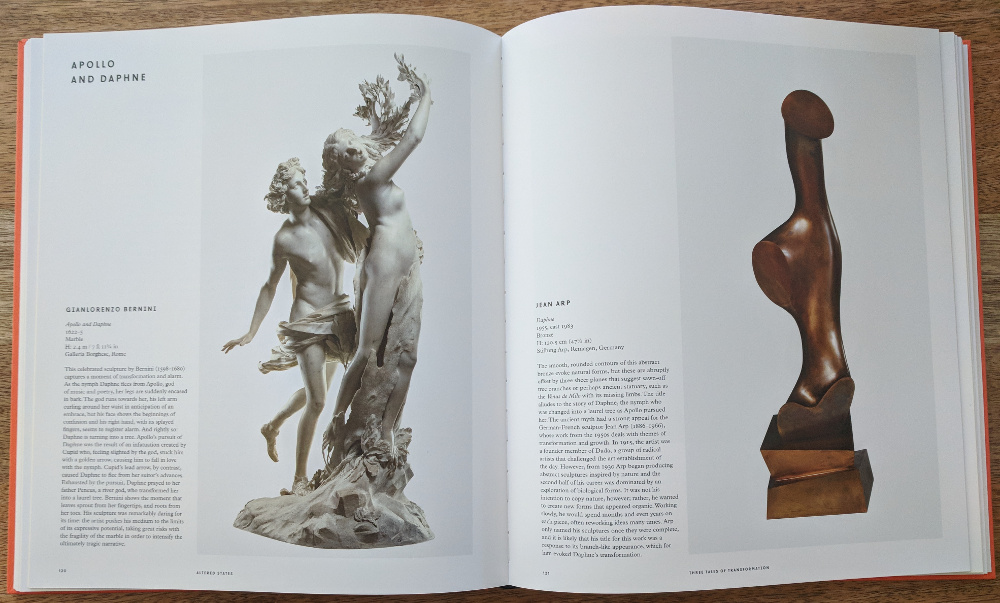

the story of Apollo and Daphne: Daphne escapes the lovestruck Apollo by begging a river god to transform her into a tree;

-

the story of the minotaur and of his slayer, Theseus, the founding hero of Athens.

The book features direct artistic references to these stories, from Greek vases to Renaissance paintings and contemporary sculptures. It also includes some modern art that may or may not intentionally reference classical mythology, but that shows some parallels in theme or expression.

Book cover (partial view). The "flares” of the sun include references to the myths explored in the book. (Credit: Phaidon Press. Fair use.)

At 250 x 290 mm (11 3/8 x 9 7/8 in), the book’s format gives these works of art the space they deserve. The captions are clear and often briefly retell the myth that is being discussed. That makes for some repetition in a single reading, but it also makes it easy to open the book at any page without requiring additional context.

As with any art book like this one, it’s possible to quibble about the works that were chosen or overlooked. For example, it will probably take another generation until editors choose to include art from games like Apotheon, a gorgeous indie platformer that brings the artistic style of ancient Greek pottery to life—to say nothing of the ubiquitous references to mythology in big-budget entertainment like God of War.

Apollo and Daphne (1622-25, Bernini) side-by-side with Jean Arp’s Daphné (1955). (Credit: Phaidon Press. Fair use.)

To me, this speaks to the still austere relationship we have with classical myths. In fact, ancient art was colorful, often lewd, and a form of mass entertainment. It provided common reference points in everyday life, it served propaganda purposes, it blended belief with pure pleasure.

While Flying Too Close to the Sun only hints at this, it is a joy to page through the high quality reproductions and photographs, to explore the content of complex paintings with helpful captions, and to become more familiar with the details of these myths. Recommended.