Latest reviews

In the United States, the term “liberal” has become associated with the soup of center-left to center-right ideas promoted by the US Democratic Party, and it would be overly generous to ascribe to those ideas any coherent ideological foundation. Historically, liberalism (or “classical liberalism”) has a more specific meaning and is linked to the writings of figures like John Locke, Adam Smith, John Stuart Mill and Alexis de Tocqueville.

The importance of understanding what these individuals truly said and did has been elevated by what The Baffler called the “Classical Liberal Pivot”, the attempt by reactionaries ranging from outgoing GOP Speaker of the House Paul Ryan to InfoWars alumnus Paul Joseph Watson to frame their ideas through reference to a past most people only have a patchwork knowledge of.

Liberalism: A Counter-History by Domenico Losurdo (d. 2018) was published in 2011 and limits itself largely to the analysis of liberal thought up to the 20th century, with occasional reference to 20th century writers like Friedrich Hayek and Ludwig von Mises. As a counter-history, it intends to focus on the less well-known aspects of liberal ideology.

In particular, the book is concerned with how liberal ideology frequently defined civilization and humanity precisely in such a way as to support the goals of regional power elites at the time: to maintain and extend the system of slavery in the American South, to displace or exterminate Native Americans, to commit atrocities in French Algeria, Ireland or the British colonies, to coerce the poor into labor or military service, and so on.

To support this thesis, Losurdo primarily cites the writings of liberals themselves. Let’s work backwards: von Mises, a hero to free market libertarians, wrote in Liberalism, published in 1927:

It cannot be denied that Fascism and similar movements aimed at the establishment of dictatorships are full of the best intentions and that their intervention has for the moment saved European civilization. The merit that Fascism has thereby won for itself will live on eternally in history.

The Mises Institute complains bitterly that this quote is taken out of its context (in context, von Mises views Fascism as an “emergency makeshift”), but it’s hard to say how any celebration of Fascism’s eternally won merit can be rescued by context. This quote may be surprising, but it is mild stuff compared to the ideas of de Tocqueville, who celebrated the Opium War (a war waged by Britain to force China to buy opium!) with these words (emphasis mine):

I can only rejoice in the thought of the invasion of the Celestial Empire by a European army. So at last the mobility of Europe has come to grips with Chinese immobility! It is a great event, especially if one thinks that it is only the continuation, the last in a multitude of events of the same nature all of which are pushing the European race out of its home and are successively submitting all the other races to its empire or its influence. Something more vast, more extraordinary than the establishment of the Roman Empire is growing out of our times, without anyone noticing it; it is the enslavement of four parts of the world by the fifth. Therefore, let us not slander our century and ourselves too much; the men are small, but the events are great.

First Opium War display in the Shenzhen Museum. Alexis de Tocqueville celebrated the war as part of “the enslavement of four parts of the world by the fifth”. (Credit: Huangdan2060. Public domain.)

How can such ideas be reconciled with any concept of “liberty”? Losurdo unpacks this contradiction masterfully. Liberalism has consistently resolved the contradiction by defining the world into a “sacred” and a “profane” space. The “sacred” space is the one where liberty has to to be defended against despots; the “profane” space is that occupied by people who are inferior, less than human, “wild beasts”, rightly conquered, justly enslaved.

This profane space was reserved for women, the native populations of countries subjected to settler-colonialism, the Africans abducted in murderous journeys to serve as slaves in the colonies, people convicted of crimes (however immoral the basis of the conviction), the poor, the disabled, and so on, and so forth.

And it is with this distinction in mind we can understand that John Locke, “the father of liberalism”,

regarded slavery in the colonies as self-evident and indisputable, and personally contributed to the legal formalization of the institution in Carolina. He took a hand in drafting the constitutional provision according to which ‘every man of Carolina shall have absolute power and authority over his Negro slaves, of what opinion or religion soever.’ Locke was ‘the last major philosopher to seek a justification for absolute and perpetual slavery’. However, this did not prevent him from inveighing against the political ‘slavery’ that absolute monarchy sought to impose. [p. 3]

Perhaps nowhere was the contrast between rhetoric and reality more stark than in the American Revolution—a revolution in significant part undertaken to continue America’s genocidal expansion westward (which the British sought to limit), while perpetuating a horrific regime of hereditary chattel slavery. It is for these reasons that Losurdo refers to the new American nation as a “master-race democracy” and calls racial chattel slavery and liberalism a “twin birth”.

Losurdo quotes Theodore Roosevelt, who called “the inability of the motherland country to understand that the freemen who went forth to conquer a continent should be encouraged in that work” the “chief factor in producing the Revolution”; Roosevelt complained that Britain wanted to “[preserve] the mighty and beautiful valley of the Ohio as a hunting-ground for savages”. [p. 303]

Yet, it was the rhetoric of the American Revolution that inspired the French Revolution, which in turn inspired the Haitian Revolution by self-liberated slaves. Fearful that such an authentic struggle for liberty might lead to slave rebellions in the United States, Thomas Jefferson assured a French diplomat that “nothing would be easier than to furnish your army and fleet with everything, and to reduce Toussaint to starvation”. When the revolution ultimately succeeded, Jefferson imposed a crippling embargo that would last nearly 60 years.

Losurdo contrasts liberalism with the “radicalism” of the Haitian and French revolutions. It was precisely people in the liberal tradition who often argued and fought against broad liberation, whether it’s the abolition of slavery or the expansion of suffrage, limits on working hours and child labor, the recognition of trade unions, and so on. As new rights were won, the line between “sacred” and “profane” spaces shifted.

The author acknowledges that liberalism is, above all, an ideology adaptable to its time and place. Few “neoliberals” would argue for the re-introduction of child labor in wealthy countries, but many would describe horrific labor conditions in the rest of the world as a necessary evil (or even positive good) that’s part of economic development. Here we see a similar division of the world into “sacred” and “profane” spaces, but under greatly altered parameters.

The Verdict

Like many other academic writers, Losurdo is inclined to repetition, though to his credit, he often reinforces earlier arguments with new material. References to writers, historical figures and events are introduced rapidly, and I found myself looking them up on Wikipedia more than once to get my bearings.

A more serious criticism of the book is its uncritical use of derogatory terms like “redskins” throughout, and its relative silence on the role of women (and the patriarchal aspects of liberal ideology). Moreover, Losurdo makes no serious effort to draw the connections and parallels between “classical liberalism” and modern liberal or libertarian thought.

Nonetheless, if we want to recognize the patterns of history in the present day, we have to first know what these patterns are. Liberalism: A Counter-History is an important contribution to recognizing the rhetoric of liberation that may overshadow, or even enable, the oppression of those not included in its “sacred space”.

Among the 50 U.S. states, Mississippi has the lowest per-capita GDP and the highest poverty rate when not adjusted for cost-of-living. The state capital, Jackson, is about 80% Black or African-American; the city was named after slave-owner president Andrew Jackson who once placed an ad for the capture of a runaway slave promising “ten dollars extra, for every hundred lashes any person will give him, up to the amount of three hundred”.

Given the present and historical context, the election of Chokwe Lumumba as Jackson’s mayor, followed soon after his death in 2014 by that of his son Chokwe Antar Lumumba, upon a radical platform of political and economic liberation may defy stereotypes about the Deep South. But it is from the history of enslavement, terror and oppression that liberation movements emerged.

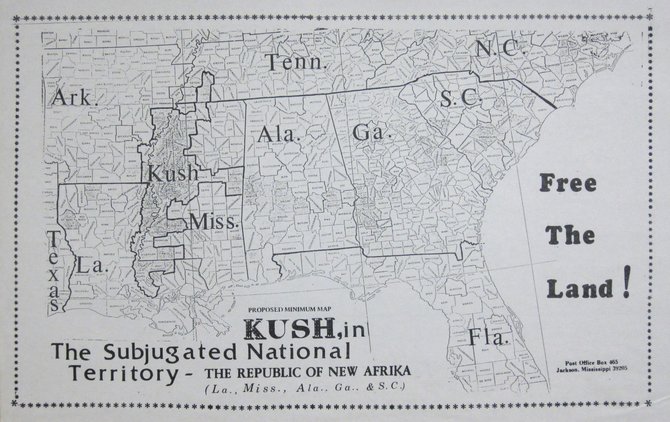

Cooperation Jackson is the movement that helped elect the Lumumbas, and which is seeking to build a bottom-up, co-operative economy not just in Jackson, but in the entire black-majority cross-state area referred to as the Kush (after an ancient African kingdom). Beyond its co-op elements, the movement seeks to mobilize the local community through assemblies to enact changes on the ground and to push for social and economic liberation.

In the early 1970s, the Provisional Government of the Republic of New Afrika planned for the Kush District to serve as power center for a new black-led nation in the South. (Credit: Republic of New Africa. Fair use.)

In practice, this vast ambition translates into much more tangible projects—urban farming and efforts to co-operatively run restaurants, grocery stores, and a fabrication center, for example.

Jackson Rising is a collection of essays dating to different points over the last few years, describing practical progress and laying out the movement’s vision for the future. The tension between what the movement seeks to achieve and what it can realistically accomplish with limited resources is palpable, and Cooperation Jackson’s recently published 2018 in Review describes the challenges of maintaining a coherent movement in light of these fundamental obstacles and ideological tensions within the movement.

The book can only be understood at offering snapshot insights into this ongoing experiment. The assortment of essays unfortunately suffers from a fair bit of repetition (the story of the elder Lumumba’s death in office, and the movement’s efforts to pick up from this this setback, is re-told multiple times, for example), and not all essays add much to the reader’s understanding.

One definite highlight of the book is the essay by Jessica Gordon Nembhard about the history of African American co-operative economic efforts, which were often a form of mutual aid in the face of terror, segregation and oppression. In her book Collective Courage, Nembhard offers a more detailed account of this history.

If you don’t end up picking up a copy of Jackson Rising but want to learn more about Cooperation Jackson, I recommend reading the online version of another article that’s included in the book: “The Socialist Experiment” by Katie Gilbert (Oxford American, September 5, 2017). It encapsulates the movement’s work up to the time it was published very well, without glossing over the enormous challenges of transforming a city’s economy from the bottom up.

Intro

Veracity filament from Filastruder that is manufactured by Keene Village Plastics and comes with access to average diameter stats on every roll. As of 12/21/18, $25 per kg for masterpool refill. All rolls came vacuum packed with desiccant and came with large zip ties for storage and an extra sticker to put on the spool to identify the material.

Quality

All 4 rolls I’ve inspected were typically 1.74 or 1.75 average which matched the online data for the roll. Looking up the data online was a pain that required you to create an account with KVP and then enter in several different codes, some off a piece of paper in the box and some off the sticker for each spool. No impurities were seen. Masterspool refills would sometimes feed awkwardly off the roll, but not to the point where it caused issues.

Print Settings

Prusa Generic PETG Settings 230C Extruder/85C Bed 1st layer, 240C/90C Bed after 1st layer

Higher temperatures will give parts glossier look.

Recommended print settings 230-260C Extruder/70-100C Bed

Verdict

My go to PETG.

This is a simple, straightforward game, and a clone of a certain popular Android game. It provides quite a bit of fun and works as a nice break for when you need to keep yourself awake during a boring task, like studying.

The levels are randomly generated so the game always feels fresh. It can be frustratingly hard to get past the initial stages, though.

I just finished episode 1, which went over Emacs and Org-mode, PDAs, and concern over corporate control of Libre Software projects, including, among other things, the recent purchase of Github by Microsoft and how that relates to Microsoft’s history involving the infamous Halloween Memo and the “embrace, extend, extinguish” strategy.

I’ve just started episode 2, and it’s starting off really strong. I think Chris and Serge are still kind of finding a cadence, but their topics are interesting and audio quality is pretty dang decent.

Mostly, I’m just really happy to have found a quality Libre focused tech podcast, as opposed to the myriad “open source” or general Linux and technology podcasts. My podcast roll needs more of this.

In short, it tastes like cat piss.

I suppose, by the very strictest definition, it is coffee. It keeps me from falling asleep at work, which isn’t nothing. But I do find it extremely difficult to finish a cup.

I don’t think the name does the fine city of Seattle any favors.

Like many nerds of my generation, I grew up playing games like Maniac Mansion, Zak McKracken, Monkey Island and (I’ll admit it) Leisure Suit Larry. These point and click adventure games offered immersive stories, atmospheric graphics and music, challenging (and often maddeningly unfair) puzzles, a lot of humor, and memorable characters—from Stan the used boat salesman to Larry Laffer and his laughable attempts to get laid.

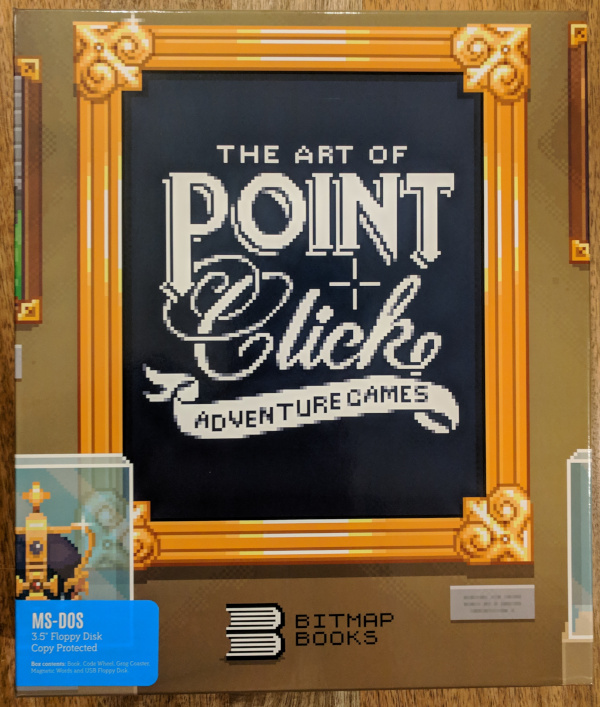

I’m also a big fan of art books—paging through gorgeous photographs or paintings on the couch is just so much more relaxing than staring at a screen. So, when I read that Bitmap Books was making an art book about point and click adventures, I had to pre-order a copy. I couldn’t resist getting the (limited) collector’s edition, which arrived a few months later in a package like a classic PC game:

Art of Point and Click Adventures Collector’s Edition (Credit: Bitmap Books. Fair use.)

Just like old-school games, in addition to the book itself, the box contained several “feelies”:

-

a USB flash drive embedded in a fake miniature floppy disk, containing a PDF of the book, some game demos, and some wallpapers;

-

a “Dial-an-Interview” wheel styled after Monkey Island’s “Dial-a-Pirate” copy protection;

-

a sheet of refrigerator magnets for constructing your own silly adventure game sentences (“Give ID card to rat”);

-

a bunch of game art postcards;

-

a “Tri-Island Brewery” grog coaster (yet another Monkey Island reference).

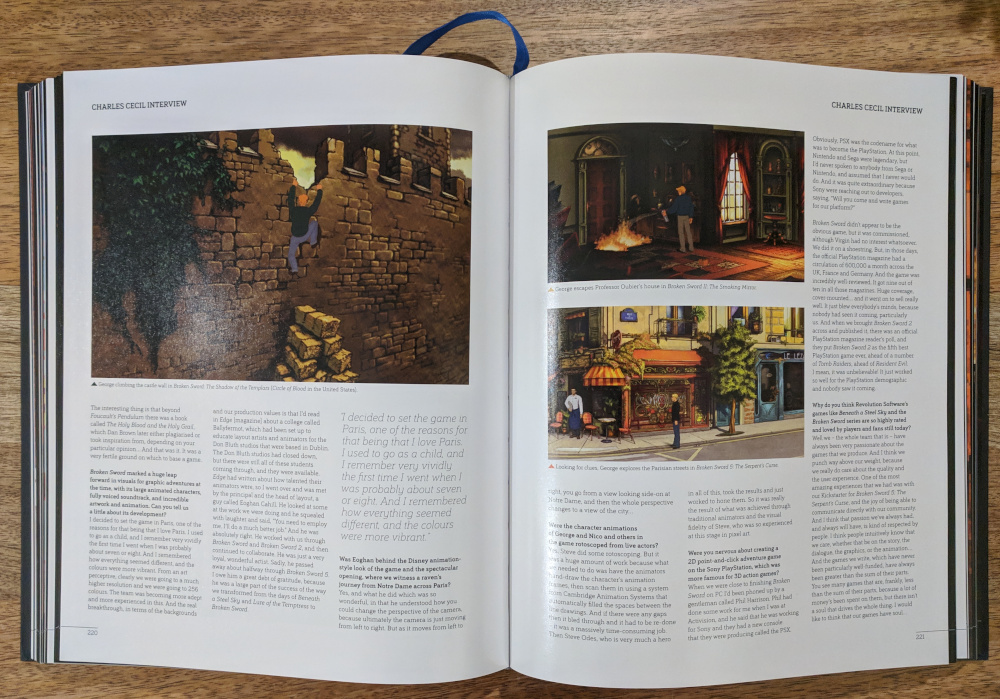

The book without the feelies, which is all you can buy from Bitmap Books at this point, is still an elegant product, with a silver foil blocked cover and a convenient bookmark ribbon. It features art from the 1980s to today, alongside interviews with the humans behind the games: people like Al Lowe (Leisure Suit Larry), Ron Gilbert (Monkey Island), Brian Moriarty (Loom), Charles Cecil (Broken Sword), Tim Schafer (Day of the Tentacle), David Fox (Zak McKracken), and Noah Falstein (Indiana Jones)—to name just a few. Instead of photographs, many of the interviewees get their own pixel art avatars in the book.

Interview with Charles Cecil alongside some art from the Broken Sword series. (Credit: Bitmap Books. Fair use.)

The game art itself is reproduced in different sizes—some screens are blown up to the size of two full pages, which, well, let’s just say that there’s a reason they call it pixel art. In addition to screenshots from the games, the book includes sketches, character art, and backgrounds (some background scenes are multiple screens wide). There is a bit of repetition, but much of it is purposeful—showing how the same scene was created in 16 vs. 256 colors, for example.

The text could have used a bit more editing here and there, and the interviews often go over the same ground (“What was it like working at LucasArts?”) again and again with different interview subjects. But they do include many interesting tidbits about the artistic process and the personal and professional stories of the genre’s luminaries before and since the games we know them for.

The book is organized chronologically, and it does give some space to recent entrants, from Thimbleweed Park (review) to The Lion’s Song (review). If you think point-and-click adventures are dead, you couldn’t be more wrong—touch devices have brought classic adventure games to millions of new fans; crowdfunding and marketplaces like Steam and Gog help sustain a thriving community of independent game makers.

All in all, if you’re like me in at least two ways—you love the genre, and you appreciate beautifully made physical books—I highly recommend getting a copy of The Art of Point-and-Click Adventure Games, or putting it on your wishlist. This is not a book to turn to for critique; it is unadulterated joy and nostalgia. Beyond that, it’s inspired me to try out a few games I didn’t know about before.

Thanks to projects like ScummVM, commercial re-releases, and abandonware archives, games that were copied on floppies by teenagers decades ago are still eminently playable today. Thanks to publishers like Bitmap Books, they are getting the historical recognition they deserve, not just as entertainment, but also as an art form.

Before Columbus, the Americas were home to tens of millions of people, possibly more than 100 million in total, a population greater than that of Europe at the time. The genocide that followed in the subsequent centuries—a combination of systematic extermination and diseases imported from Europe’s pestilence-ridden cities—is greater than any other known in history.

American Holocaust by David Stannard, Professor of American Studies at the University of Hawaii, was published in 1992—the quincentennial of Columbus’ first voyage. It remains one of the most authoritative works about how and why this genocide occurred.

An Old World

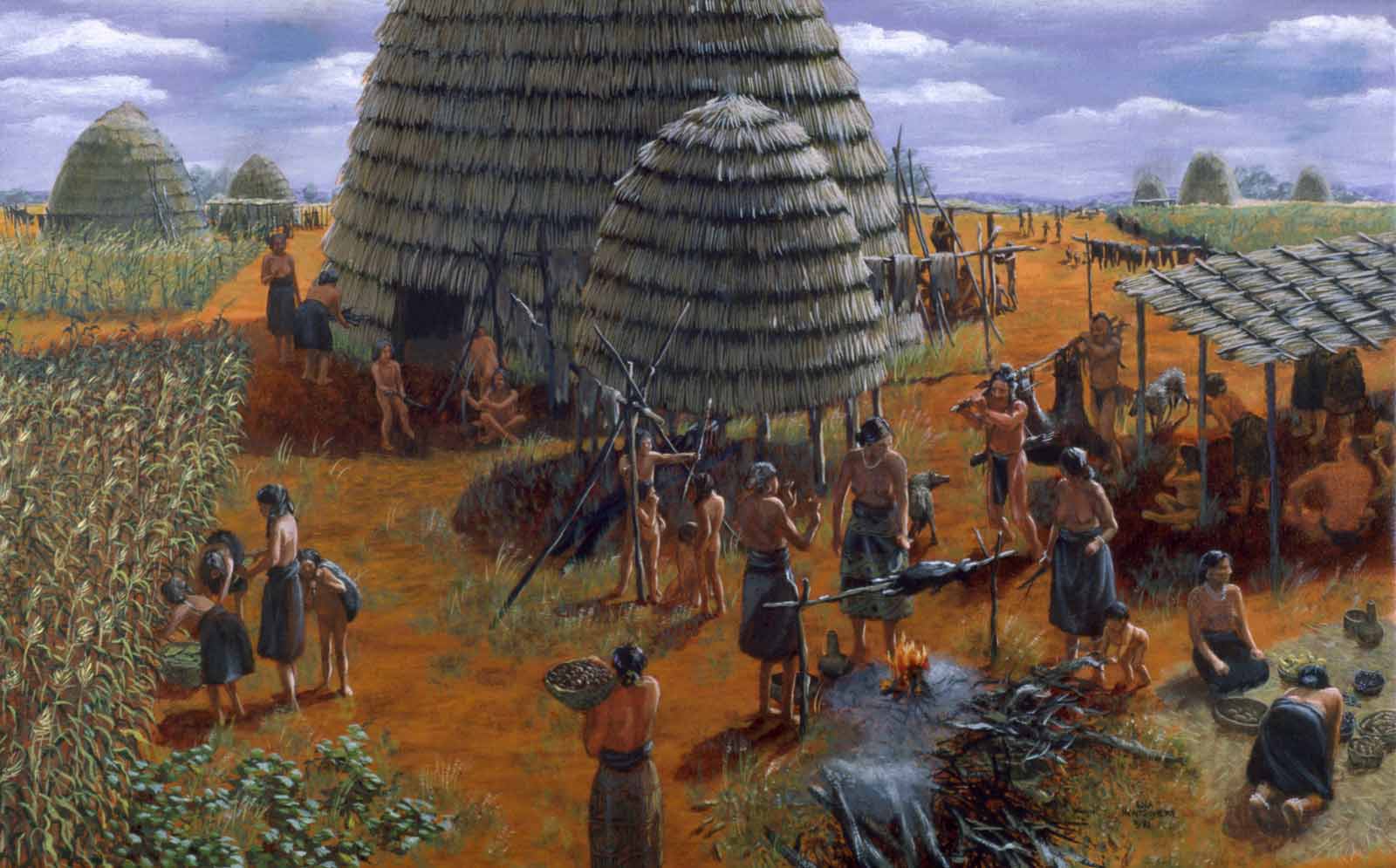

Caddo village, c. 1000 CE. (Credit: Nola Davis, Texas Historical Commission. Fair use.)

Before describing the consequences of European contact, Stannard gives us a window into what pre-Columbian societies in the Americas looked like, describing communities like the Inca, Aztecs and Maya, the Mississippian culture, and the Ancestral Puebloans.

The history of human settlements in the Americas begins at least about 13,500 years ago—and possibly as long as 40,000 years ago. During this time, the uncounted, diverse communities who lived on these vast lands developed vibrant villages and cities, sophisticated farming and irrigation techniques, and large trade networks. They built monuments, watched the stars, created geoglyphs, waged wars, made peace.

But when the threads of American history finally crossed with those of Europe, a new chapter began—and this one was to be written in the blood of multitudes.

Search for Gold

Stannard paints a vivid picture of Spain at the time of Columbus’ first voyage. This was the time of the Spanish Inquisition, of the expulsion of the Jews from Spain, of the conquest of Granada; for many, it was a time of abject poverty and disease which routinely swept through Europe (in the previous century, the Black Death had killed 75 to 200 million people in Eurasia). It was a time of prophecy, of witch-hunts, and fanaticism; Columbus himself would write a Book of Prophecies towards the end of his life.

Above all else, the Spanish sought gold to fund their wars and their fledgling empire, with the “conversion” of natives along the way being at best a secondary motive in practice. When they arrived in “Hispaniola”, they brought with them diseases that Europe’s population had become hardened to, and set to work to enslave the native population to work the mines and fields. Those who weren’t killed by disease and by the terror that the Spanish unleashed on the population, were worked to death—and before long, the natives were replaced by imported African slaves.

Market scene of Tenochtitlan before Spanish conquest by Diego Rivera (d. 1957). Note the human body part being sold on the market, which is suggestive of Aztec cannibalism, the extent of which remains heavily disputed among historians. (Credit: Diego Rivera. Fair use.)

That story would come to be repeated by the Spanish invasions throughout South America. Whether natives were friendly or hostile made no difference: the invaders sought gold, not souls, and were willing to work the population to death to get it. The biggest concern this raised in the motherland was that the conquistadors were running out of slave labor.

There were, of course, some Spaniards who were horrified by this unfolding tragedy. Most notably, Bartolomé de las Casas advocated throughout his life for the welfare of the indigenous people, but he could not halt the genocide, only chronicle it.

Genocide as Policy

In contrast with the Spanish quest for gold, Stannard describes the motives regarding the colonization of North America primarily in terms of expansion, to which the native populations were an impediment. In this settler-colonialism, the expulsion or destruction of native populations was a prerequisite for the success of the new colonies, once again aided by European diseases.

Stannard provides more evidence for this characterization than can be included in a brief review, but as it pertains to modern America, it is worth quoting the section that describes the role of the “founding fathers” of the United States in advocating for and implementing genocide (p. 119-120):

George Washington, in 1779, instructed Major General John Sullivan to attack the Iroquois and “lay waste all the settlements around … that the country may not be merely overrun but destroyed,” urging the general not to "listen to any overture of peace before the total ruin of their settlements is effected. " Sullivan did as instructed, he reported back, “destroy[ing] everything that contributes to their support” and turning “the whole of that beautiful region,” wrote one early account, “from the character of a garden to a scene of drear and sickening desolation.” The Indians, this writer said, “were hunted like wild beasts” in a “war of extermination,” something Washington approved of since, as he was to say in 1783, the Indians, after all, were little different from wolves, “both being beasts of prey, tho’ they differ in shape.”

And since the Indians were mere beasts, it followed that there was no cause for moral outrage when it was learned that, among other atrocities the victorious troops had amused themselves by skinning the bodies of some Indians “from the hips downward, to make boot tops or leggings.” For their part, the surviving Indians later referred to Washington by the nickname “Town Destroyer,” for it was under his direct orders that at least 28 out of 30 Seneca towns from Lake Erie to the Mohawk River had been totally obliterated in a period of less than five years, as had all the towns and villages of the Mohawk, the Onondaga, and the Cayuga.

(…)

Or Jefferson, for example, who in 1807 instructed his Secretary of War that any Indians who resisted American expansion into their lands must be met with “the hatchet.” “And … if ever we are constrained to lift the hatchet against any tribe,” he wrote, “we will never lay it down till that tribe is exterminated, or is driven beyond the Mississippi,” continuing: “In war, they will kill some of us; we shall destroy all of them.”

These were not offhand remarks, for five years later, in 1812, Jefferson again concluded that white Americans were “obliged” to drive the “backward” Indians “with the beasts of the forests into the Stony Mountains”; and one year later still, he added that the American government had no other choice before it than “to pursue [the Indians] to extermination, or drive them to new seats beyond our reach.” Indeed, Jefferson’s writings on Indians are filled with the straightforward assertion that the natives are to be given a simple choice-to be “extirpate[d] from the earth” or to remove themselves out of the Americans’ way.

This policy of genocide was continued by future presidents—notably Andrew Jackson, whose “Indian Removal Act” was exactly what it sounds like (a policy of murderous ethnic cleansing). About Jackson’s ascend to the presidency, Stannard writes (p. 121-122):

Then, in 1828 Andrew Jackson was elected President. The same Andrew Jackson who once had written that “the whole Cherokee Nation ought to be scurged.” The same Andrew Jackson who had led troops against peaceful Indian encampments, calling the Indians “savage dogs,” and boasting that “I have on all occasions preserved the scalps of my killed.” The same Andrew Jackson who had supervised the mutilation of 800 or so Creek Indian corpses—the bodies of men, women, and children that he and his men had massacred—cutting off their noses to count and preserve a record of the dead, slicing long strips of flesh from their bodies to tan and turn into bridle reins. The same Andrew Jackson who—after his Presidency was over—still was recommending that American troops specifically seek out and systematically kill Indian women and children who were in hiding, in order to complete their extermination: to do otherwise, he wrote, was equivalent to pursuing “a wolf in the hammocks without knowing first where her den and whelps were.”

Such explicitly genocidal language was used into the 20th century, including by Theodore Roosevelt, who once remarked: “I don’t go so far as to think that the only good Indians are dead Indians, but I believe nine out of ten are, and I shouldn’t like to inquire too closely into the case of the tenth.”

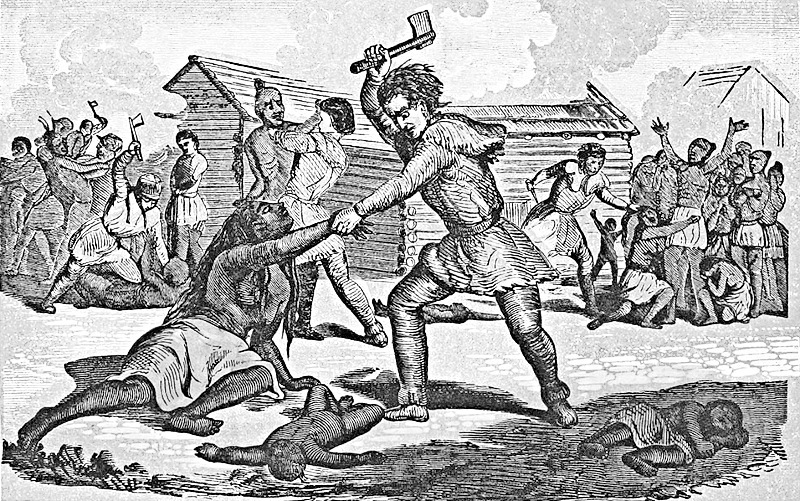

It is rare that the colonists recognized their own actions as “massacres”, but the 1782 mass murder of 96 peaceful Christianized natives in Ohio (in the majority women and children) is an exception; it was embarrassing in a context where usually a pretext was sought for expulsion or mass murder. The event is known as the Gnadenhutten Massacre. Illustration from Henry Howe, The Great West (1852).

Today’s occupant of the White House is a noted admirer of Andrew Jackson; he placed Jackson’s portrait in the Oval Office (where it hung during a ceremony honoring Navajo code talkers) and cited him as a role model on many occasions.

Ideological Foundations

Stannard links the policies of genocide in the Americas to the fanatical religious ideology that the Spanish and the English brought with them: an ideology that often venerated suffering, that was obsessed with sex, that carried within it ideas of “monstrous races” in need of either salvation or destruction.

He connects these ideas to their precursors in antiquity (especially the dehumanization that accompanied the institution of slavery), while noting how the rise of Christianity hardened them into fanaticism, a subject on which Catherine Nixey elaborates in her 2018 work, The Darkening Age.

These beliefs made it all too easy to regard the natives as “savages” and “beasts”, less than human, beyond reason. The fact that many of the societies of the Americas had more permissive attitudes towards sexuality, very different concepts of property, and a large number of beliefs that were totally alien to the invaders—all this removed them further from the prevailing concept of what it means to be human.

Even the Spanish missions, institutions supposedly meant to bring Christianity and “civilization” to the natives were, in reality, little more than concentration camps where natives were worked to death, if not killed by disease (facilitated by the tiny amount of living space allocated to each inhabitant). Stannard cites the example of the missions of California, a topic on which author Elias Castillo recently elaborated in the book A Cross of Thorns: The Enslavement of California’s Indians by the Spanish Missions.

The Verdict

Of course, to this day, there are plenty of people that will dispute the facts recounted by Stannard, or look for ways to equivocate: Surely disease was by far the more deadly force, so this was not genocide! Surely some natives attacked settlers, so the goal was not extermination but self-defense! Surely the claims against the Spanish were exaggerated by other European powers! Surely there were times of peaceful coexistence, so genocide cannot have been the political intent!

None of these defenses withstand even the slightest scrutiny; Stannard anticipates most of them, and cites sources that largely speak for (or against) themselves. Where he makes assumptions that some will criticize (e.g., in arguing for larger population numbers than some scholars accept), he cites credible research and “shows his work”, letting the reader draw their own conclusions. My only significant criticism of the book is that the photographs and illustrations in the paperback edition are of extremely poor reproduction quality—you may have more luck with the hardcover version.

American Holocaust, then, is an essential work to truly understand the origin story of modern “civilization”. For if we are to create a society that is in fact worth being called a civilization, we must be willing to reflect upon the beliefs and values that made the genocide in the Americas possible.

Remnants of these beliefs—including the expansionist, extractive ideology of settler-colonialism—still animate human action as we face the twin challenges of the 21st century: avoiding catastrophic climate change and avoiding nuclear war. To name just two examples, conflicts like the protests by Native-Americans against the Dakota Access Pipeline, or settler violence against Miskito indigenous people in Nicaragua, show that this past isn’t dead—it’s not even past.

Stephen King is known for his prolific output of novels and short stories. Having grown up reading books like Stark, It, The Stand and Needful Things, I find it hard to resist the temptation to pick up anything that has his name on it. Usually that’s been a pretty good bet. Usually.

Elevation comes in at 160 pages in a compact form factor, making this more of a short story than even a novella, certainly not “a novel” as it is billed on the cover. It is the story of Scott Carey, a man who mysteriously loses weight without changing in appearance.

As the process accelerates, he finds his mood “elevated” as well. With newfound energy, he tries to connect with a lesbian couple who recently moved into his conservative town, and who are facing prejudice from the conservative majority of the community.

At the annual “Castle Rock Turkey Trot”, a 12K race, Scott finally manages to bridge the gap with the haughty member of the lesbian couple, Deirdre McComb, whose arrogance is a way to protect herself from bigotry.

It’s a kitschy political allegory not entirely without its moments: King’s depiction of the race is a high point in the short story, and the ending is simple but moving. If it had been part of a short story collection, I would rate it three stars. As a stand-alone entry, currently priced at $8 in the ebook version on Amazon, it doesn’t measure up. (You’ll get the whole Wool Omnibus for less, and trust me, it’s a lot more entertaining.)

Opensource ad blocker for Android that filters all outbound requests for ads and tracking using any combination of premade lists, whitelist and blacklist. You can also switch dns providers by selecting from a list or adding one. UI is simple and effective.

Blokada works by using Android’s vpn feature to route all outbound requests through it. This allows it to filter all requests that come from the device.

Long Term Update

After 6 months of usage, the only issue that came up is occasional issues with program staying alive. The app silently died so I didn’t notice for a while. Turning on the Keep alive option under advanced settings seems to fix the issue. This puts up an always on notification to keep Blokada alive. This means you’ll have 2 notifications up almost all the time for this app.

Verdict

This is a must have app for Android