Latest reviews

OpenStreetMap, despite having “map” in its name is more than just a map, and certainly more than just a street map. It’s a collaboratively authored and edited geodatabase. You can enter anything that is objectively verifiable “on the ground” into it, and conversely you can find almost everything in it, though without any claim of accuracy, completeness or up-to-date-ness. (Though if you notice anything to be inaccurate, incomplete or out-of-date, you’re free to improve it.) The data for the complete “planet” can be freely downloaded and analyzed, or used to build your own maps, navigation, or what-have-you. There’s a whole ecosystem of third-party services, tools and derived works (such as maps) that has developed around that.

The data model is unlike the others commonly found in the GIS world, which makes analysis of OpenStreetMap data with general-purpose GIS tools cumbersome at times.

Disclosure of conflicts of interest:

I am:

- a user and contributor of OpenStreetMap

- a member of the OpenStreetMap Foundation (OSMF)

- a board member of the Swiss OpenStreetMap Association (SOSM), the Swiss local chapter of the OSMF

Ein nettes, einfach zu bedienendes aber nicht so leicht zu meisterndes Spiel für zwischendurch. Wenn ich es länger spiele, wird mein FairPhone 2 allerdings recht heiß …

As usual, I’m late to the party. Gone Home caused quite a stir when it came out in 2013. Many critics and players loved it; some angry gamers hated it, some of that hatred helped fuel the misogyny horror show known as Gamergate. Today, Gone Home is available for Windows, Linux, Mac, Switch, PS4, Xbox One, iOS, and your toaster. It remains a polarizing game, and it’s not hard to see why. You can finish the game in 2-3 hours; it features no conventional “puzzles” or action, and one of its central themes is a lesbian coming-out story.

Gone Home is a first-person exploratory game. It’s the mid-90s, you’re 21-year-old Katie Greenbriar, home from your big European adventure, only to find that your parents and sister are not there. What happened? While a storm rages outside, you walk from room to room of the “psycho house” your family moved into, trying to find clues to their disappearance. The home is littered with paper—handwritten notes, letters, photographs, receipts, books, post-its, and so on. Some notes lead to audio logs that add to the evolving story.

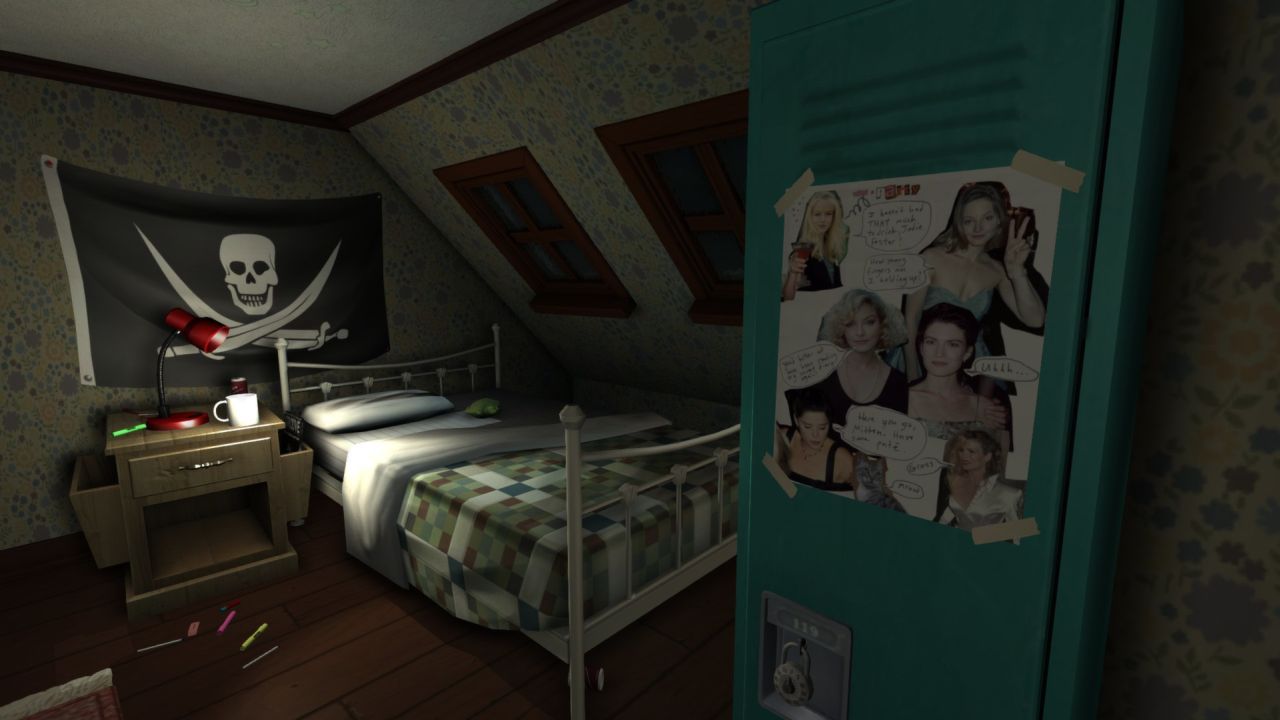

To find out what happened to your sister, you may have to figure out a way into her personal locker. (Credit: Fullbright. Fair use.)

Unlike a point-and-click adventure, where almost every item you encounter has some role to play, here you can interact with countless objects—pens, glasses, knick knacks, etc.—but most of them have no relevance to the plot. You have to sort through the messy home, and the house has a few secrets of its own.

There’s remarkable attention to detail, especially in the riot grrrl aesthetic of your sister’s belongings. In addition to zines and posters, you can even pick up and play cassettes with music featuring bands like Bratmobile and Heavens to Betsy.

Gaming is now a bigger tent than it ever was, and just as writing has room for short stories, gaming has room for experiences like this, where your own interpretation of a story takes precedence over puzzles or action.

My biggest criticism is that the sheer abundance of paper clues made the game a bit less atmospheric, more like an artificial world that an author has littered with stuff I’m supposed to find. Someone needs to teach the Greenbriars about recycling.

The game makes up for flaws like this with a layered story that is moving and well-told. If you’re not looking for a 20 hour diversion or a 200 hour addiction, and if exploring a story on your own terms sounds appealing, then I recommend giving Gone Home a spin. I wouldn’t have bought it at the regular price of $15, but at a discounted $6 price on GOG, it was well worth the money.

Republic wireless is a unqiue cell service provider. They use an always on app to provide service through a combination of cell and VOIP. They only provide service to certain phone models that are listed on their site.

Cost

The prices are good if you use less than 2GBs of data, 2GBs and unlimited talk and text is $25.

Service

Coverage has been fine since they use brand name cell networks to provide coverage. They route all service through WiFi when possible so you always have good service at hotspots.

Gotchas

Republic tries to hide the magic they do behind the scenes to provide low cost service which has led me to run into some weird cases where I had issues.

- Phone numbers are classified as landline

- venmo won’t allow you to register non-mobile number

- calls are routed through underlying numbers that serve multiple endusers

- gotten multiple calls that seem meant for other people, unclear if for my number or the underlying number

- app controls your service

- had the app crash one day(likely my fault) and calls wouldn’t go through even to voicemail and texts that were sent to me never showed up

- weird interactions are possible see https://help.republicwireless.com/hc/en-us/articles/360024889393-Can-Security-Apps-Affect-My-Call-Quality-

- You must be on latest version of Android for your device for activation

- running a version of android that is NEWER than what the manufacturer has released will be rejected, they verify this using build id property

Verdict

Service has worked well the majority of time for low cost. The problem is that other providers have plans for similar cost that don’t require dealing with all the weird gotchas that come with Republic’s service.

From the projects homepage, “A free-as-in-freedom re-implementation of Google’s proprietary Android user space apps and libraries.”

Requirements

You’ll need a ROM with signature spoofing enabled natively or using a patcher like nanodroid-patcher. Magisk is optional but will help pass safetynet. Installation using nanodroid and Magisk is fairly easy.

GMSCore/UnifiedNlp

This is app implements play services and location services. The location services piece allows you to choose your location provider with options to use local or online databases. This saves you from sending your location to google several times a day when NOT using GPS and more when you are. I didn’t run many apps from the google store but in general had few issues even with apps that were supposed to use google services. Although, one app I needed could not get location and the log showed the same error as a bug report from over a year ago.

GsfProxy

This worked well when setup correctly but required that apps be installed after microg or the apps wouldn’t register correctly. GCM still sends data to google as an intermediary, the code running on your device is FOSS to limit your exposure to google. Some apps will probably miss funcationality since all of the messaging apis aren’t implemented. There’s no database telling you what will or won’t work, you have to find out for yourself.

Safetynet

This is a service provided by google to check that your phone has not been modified or applications won’t allow you to use them. Passing safetynet is a constant cat and mouse game with google changing setting so one day you’ll pass and then you won’t. Magisk should help by hiding your modifications but issues still seem to crop up based on the open issues.

Long Term Update

After a year plus of usage, I had a generally positive experience but, had to switch back after needing to use an unsupported app and unifiedNlp stopped working correctly.

Verdict

A much needed app to put google at arms length on your phone. Usage is not for the faint of heart. You’ll want to limit your apps that use google services for the best experience. You’ll also have to be a part time sys admin with backups and updates of the device for when somethings goes wrong.

Ted Chiang’s stories are meticulously crafted thought experiments. Many of them are science fiction; “Story of Your Life“, first published in 1998, became the basis of the 2016 blockbuster movie Arrival. Others defy classification. The 2001 story “Hell Is the Absence of God” imagines a world in which God, angels, heaven and hell are real—and angelic visitations are more like natural disasters, leaving death and destruction in their wake.

Exhalation is the second collection of Chiang stories. It contains nine stories, two of which have never been published before. My favorite one is “Anxiety is the Dizziness of Freedom” (the title references an observation by existentialist philosopher Søren Kierkegaard).

The premise is that the many-worlds interpretation of quantum mechanics is correct. Through laptop-like consumer devices, anyone can create branch universes and communicate with their duplicates—their “paraselves”—in those universes, for a limited time.

The devices are called Prisms, which stands for “Plaga interworld signaling mechanism”. Why “Plaga”? That’s never explained, but some googling reveals a 1995 pre-print by Rainer Plaga titled “Proposal for an experimental test of the many-worlds interpretation of quantum mechanics”; the mechanism described in Chiang’s story matches the description in Plaga’s paper. This gives you an idea of the attention to detail in Chiang’s work.

From this premise, Chiang explores how the knowledge of an infinite number of universes—and the ability to speak with the inhabitants of some of them—would impact crime, grief, love, and loss. Through his characters’ experiences, Chiang makes us imagine that we might live in just such a world one day, while conveying a powerful moral lesson for the one we do live in today.

Other ideas Chiang explores in Exhalation include:

-

What would a world look like in which, instead of discovering ever more irrefutable evidence for the evolution of life on an Earth that’s billions of years old, scientists had discovered irrefutable evidence of a single creation event thousands of years ago? What would the relationship between science and religion be in such a world, and what would shake its faith?

-

What if we could keep life-long recordings of everything we see, hear and say, and search those recordings through the power of thought alone? How would this technologically mediated perfect memory impact our behavior, our relationships, our sense of self?

-

What if raising a healthy, capable artificial intelligence was just as time-consuming and difficult as raising a healthy, capable human child? How would such AI children be treated in a world that regards them as “software objects”?

I found “The Great Silence” (originally written to accompany an art exhibit) and “What’s Expected of Us” (inspired by the neuroscience of free will) to be the least captivating, but both are quite brief, and they are still fine stories. The best stories in Exhalation are so good that the entire volume deserves five stars. It’s been 17 years since Chiang’s first collection, Stories of Your Life and Others, was published, but it was worth the wait.

In Nutshell, Ian McEwan constructed a murder mystery told from the perspective of an unborn protagonist. The narrator of Machines Like Me, McEwan’s latest novel, is not a fetus, but he still somehow comes across as a less developed human being.

Charlie Friend is an aimless drifter who, after many failed schemes, makes just enough to get by through stock market trades. After stumbling upon an inheritance, Friend decides to purchase one of the first androids with human-like intelligence. Of course, this machine being is called Adam.

The book is set in an alternative version of the 1980s in which the technological visions of tomorrow are the reality of yesterday. There’s no subtlety when Friend explains: “The present is the frailest of improbable constructs. It could have been different. Any part of it, or all of it, could be otherwise.“

The compounding differences between this timeline and ours create a path of breadcrumbs through the narrative: America never dropped the nuclear bombs; Alan Turning never committed suicide; JFK was never assassinated, and so on.

The main story revolves around the relationship between Charlie, Adam, and their (mutual) love interest, Charlie’s neighbor Miranda. What could have been a simple love triangle gets a lot more complicated as a secret from Miranda’s past is gradually revealed, and the ethics of both human and AI are put to the test.

Reactions to the book have been mixed. Negative reviews describe McEwan’s alternative history as a gimmick to bring Alan Turing into the narrative. My own impression is that in his later works (inculding Nutshell and The Children Act), McEwan is feeling an increasingly urgent need to voice his political views, and that every part of Machines Like Me serves this larger political purpose

In Nutshell, I found the politics jarring, with the author’s own voice coming through too clearly in the unborn narrator’s observations. In Machines Like Me, the story itself is the instrument of political expression.

In McEwan’s alternative timeline, Britain experiences Brexit-like political polarization and confusion in the 1980s, triggered by an alternative outcome to the Falklands War, and by the unavoidable job losses that come with AI-driven automation. The tribulations of the human protagonists mirror this setting of humanity’s tribalism laid bare. When its political argument turns toward futility, Machines Like Me becomes a lament for humanity.

The Verdict

McEwan is a master storyteller, but while sci-fi is certainly new territory for him, many other talented writers have visited these lands before. In an interview with The Guardian, McEwan gave a save a somewhat disdainful description of sci-fi (“traveling at 10 times the speed of light in anti-gravity boots”), and promised a more nuanced take on the “human dilemmas” that sentient AI would bring with it.

In truth, Machines Like Me is not a groundbreaking book by any stretch. It’s an aging liberal’s personal reflection on the future of the world around him, cast into a re-imagined past. I also found it to be an engaging story, not as powerful as the author’s masterpiece (Atonement), but certainly entertaining and thought-provoking.

Towards the end of Capitalism vs. Freedom: The Toll Road to Serfdom, author Rob Larson recounts the 2013 Savar building collapse in Bangladesh. 1,134 people died in the collapse of the building—a horrifying death toll that was the direct results of workers being ordered back into the building after a temporary evacuation due to the discovery of cracks. Managers threatened to withhold a month’s worth of wages if workers did not return to the death trap.

Imagine for a moment being faced with that choice. You know that there’s a real risk the building will collapse. But you also know that, without your job, you may not be able to feed your family. It’s hard to imagine a less free choice than one which forced workers to return into a doomed building, leading to a death toll that rivals the deadliest terror attacks.

And yet, in the world of free market extremism, this kind of choice is perfectly free. After all, the state did not force workers to enter the factory at gunpoint. And if there’s a problem, the market, over time, will fix it. To regulate the conditions of factories, on the other hand? That’s the road to totalitarianism.

Freedom to suffer

Rob Larson’s 228 page book seeks to debunk this Panglossian view of freedom and power, where everything is fine until the state gets involved. This belief system is exemplified in the writings of prominent free market theorists like Milton Friedman and Friedrich Hayek.

Larson, a professor of economics at Tacoma Community College in Washington State, calls the writings of Friedman, Hayek et al. “weak-sauce ideology” and describes libertarianism as a sham that has only gained any traction at all because it is being relentlessly promoted by people with power.

To make his case, Larson begins by showing how concentration of corporate power is an unavoidable tendency under capitalism, and then maps the effects of that power on various human choices.

Power narrows other people’s choices, that is the whole point, and concentrated corporate power is just as capable of doing so as the state. When Amazon.com creates an AI that automatically fires workers who take too many breaks, when those same workers pee in bottles to avoid getting fired—that’s a narrowing of human freedom, an Amazon-branded boot stamping on a human face, forever.

But corporate power is not limited to abusive working conditions. The scariest word for any libertarian should be externality, a term in economics which can be used to describe harm inflicted on people by economic activity who are not given a say in the matter. The most obvious example is toxic sludge being dumped in a river.

Climate change is the Mother of All Externalities, and Larson devotes a whole chapter to how climate change and the ongoing destruction of our home planet restrict the freedom not just of people who are alive today, but of future generations.

Larson’s book concludes with a brief history of socialist thought, and a passionate plea for a libertarian/democractic socialism that opposes extreme concentration of power in any form.

The Verdict

Larson’s writing is unvarnished and direct. This positively sets it apart from impenetrable academic writing, although at times it also comes across as needlessly snarky and flippant.

I agree with much of the author’s analysis. If the battle cry “socialism or barbarism” is to resonate again, socialism must reclaim the mantle of freedom, and refute the idea that “free” markets alone will create a society that lives up to our highest aspirations. Capitalism vs. Freedom is an important contribution towards that goal. 3.5 stars, rounded up.

Paradigm is an indie point-and-click adventure game developed by Jacob Janerka and available for Linux, Mac, and Windows. The premise is pretty straightforward: You’re a mutant with a tumor head and a moribund electronic music career, living in an abandoned town in a post-apocalyptic Neo-Soviet Eastern European country; you gradually discover that you are at the center of a conspiracy orchestrated by an anthropomorphic sloth genetically engineered to vomit candy. Okay, maybe not that straightforward.

In spite of the Eastern European-ish setting, most of the game’s cultural influences are Western: classic movies like Star Wars and Rocky, the LucasArts adventure games, Futurama, YouTube series, Australian shows and bands, and so on. The game’s developer, artist and designer, Jacob Janerka, is Australian of Polish origins, and the game is very much a reflection of what’s in his head.

Above all else, Paradigm is a classic adventure game made by someone who clearly loves and respects the genre. The game largely avoids the pitfalls that can make adventure games frustrating: illogical puzzles, deaths, dead ends, or pointless walking around.

When you’re stuck, you can even ask your own tumor for tips. You’re unlikely to need to: The game follows a fairly linear progression with mostly item or dialog-based puzzles. If you feel like it, you can take detours to discover mini-games and various hidden objects.

Mini-games, you say? Yes, but they’re not the usual tic-tac-toe level bullshit. Instead, it’s stuff like:

-

a post-apocalyptic dating simulator;

-

the game of Boosting Thugs, styled like a 16-bit beat ‘em up, but instead of fighting your enemies, you give them compliments;

-

audio cassettes spread throughout the game, containing choice content like a live belly-slapping performance.

In a half-serious adventure game like Broken Age, almost all content you find throughout the game is part of a puzzle. But in Paradigm, much of it is just there for the hell of it—you can ignore it, or have fun with it, making the attention to detail here all the more remarkable.

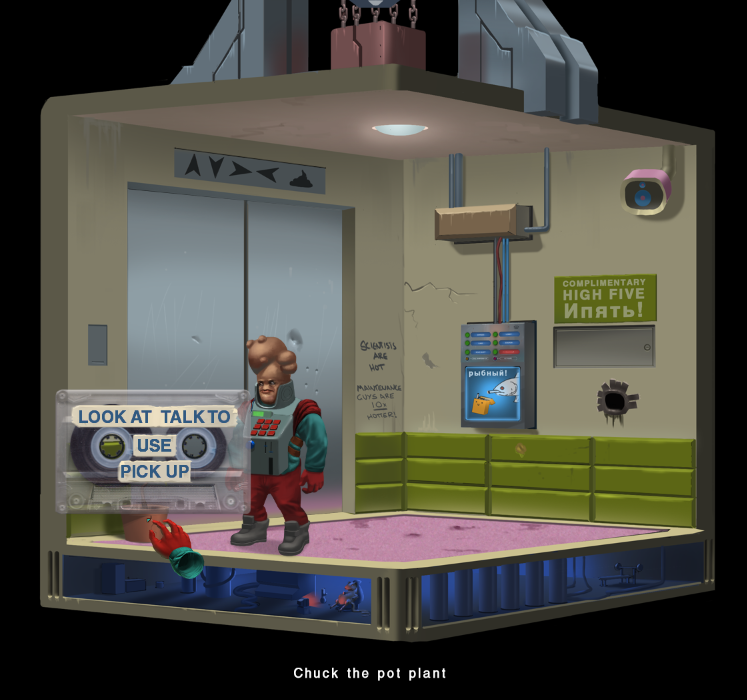

Paradigm, the main character, spends a fair bit of time in this elevator. Note the rat watching TV and the tiny rat gym, and the reference to Chuck the Plant from Maniac Mansion. (Credit: Jacob Janerka. Fair use.)

The game’s controls are reminiscent of later LucasArts titles like Full Throttle and Grim Fandango: you have a few interaction verbs that you can access through a pop up menu, giving maximum screen real estate to the game’s graphics. At different points in the game, you get access to a map for quick navigation.

Janerka did the much of the work on the title as a one person studio (the music was composed by Jonas Kjellberg) and funded the project’s completion via Kickstarter. Of course, parts of the game lack polish, and a lot of the humor is at the dad joke level and can be a bit cringe-inducing. That said, I laughed out loud a few times, so the batting average isn’t all that bad.

I played Paradigm for a total of about 8 hours, during which I looked at the walkthrough a couple of times. I paid about $5 (discounted price on GOG, currently it’s back up to $15). Even at $15 you’re likely to get good value for your dollar; if you see it at a lower price and enjoy point and click games, I would definitely recommend it.

Lutris is an all-in-one game management tool for Linux. It lets you organize your installed Linux-native games from sources like GOG or Steam, but also integrates various console emulators (from ZX Spectrum to PlayStation 3) and optimized configurations for running various Windows-only title under Linux using Wine.

Lutris is fully open source, community-maintained, and funded via Patreon (as of this writing, about $600 a month—hopefully more by the time you read this). The graphical client integrates nicely with its own game database on the web.

After you install Lutris, you can choose which “runners” you want to enable—e.g., you can choose to turn on the PlayStation 3 “runner”, after which Lutris downloads and installs the required emulator automatically (Lutris maintains its own build infrastructure to create builds of the latest releases). If a game is not in the Lutris database, you can still add it to your collection through the UI.

Through this functionality, Lutris fills an important gap in the Linux gaming ecosystem. To understand why, it’s important to look at the story of Linux gaming so far.

A brief history of Linux gaming

Early efforts to port games to Linux (Loki Entertainment, 1998-2001) or to run Windows games on Linux directly (Cedega, 2004-2009) failed commercially. For a while, it looked like Linux gaming would remain the domain of die hards who are happy with open source games like Battle for Wesnoth, emulators, and the occasional Linux port.

But today, Linux gaming is not just back, it’s thriving. There are several reasons for that:

-

Cross-platform development is the norm for popular titles, not the exception (porting to/from mobile, to/from consoles, etc.), and common game engines like Unity and Unreal support Linux.

-

Online stores like Steam, GOG and itch.io treat Linux almost as a first class citizen and have dramatically lowered the cost of distributing Linux versions (compared with putting boxes on shelves, but also with game developers maintaining their own distribution channels).

-

The stores themselves have a financial interest in seeing games ported to Linux. And while Valve’s Linux-based SteamOS project seems to be going nowhere, the company continues to invest in Linux compatibility through projects like Steam Play.

All of this means, however, that Linux gaming is still heavily dependent on commercial players who tend to favor keeping gamers within their ecosystems, and whose commitment to Linux is either constrained or entirely driven by profit motives.

While Steam is available for Linux, it’s proprietary and employs DRM; GOG’s recently launched “GOG Galaxy” application is also proprietary and, as of this writing, Windows-only. Running emulators for other platforms within the Steam client is possible, but not a first-class feature. And let’s not even talk about the proprietary nature of the metadata and reviews.

A gaming platform fit for Linux

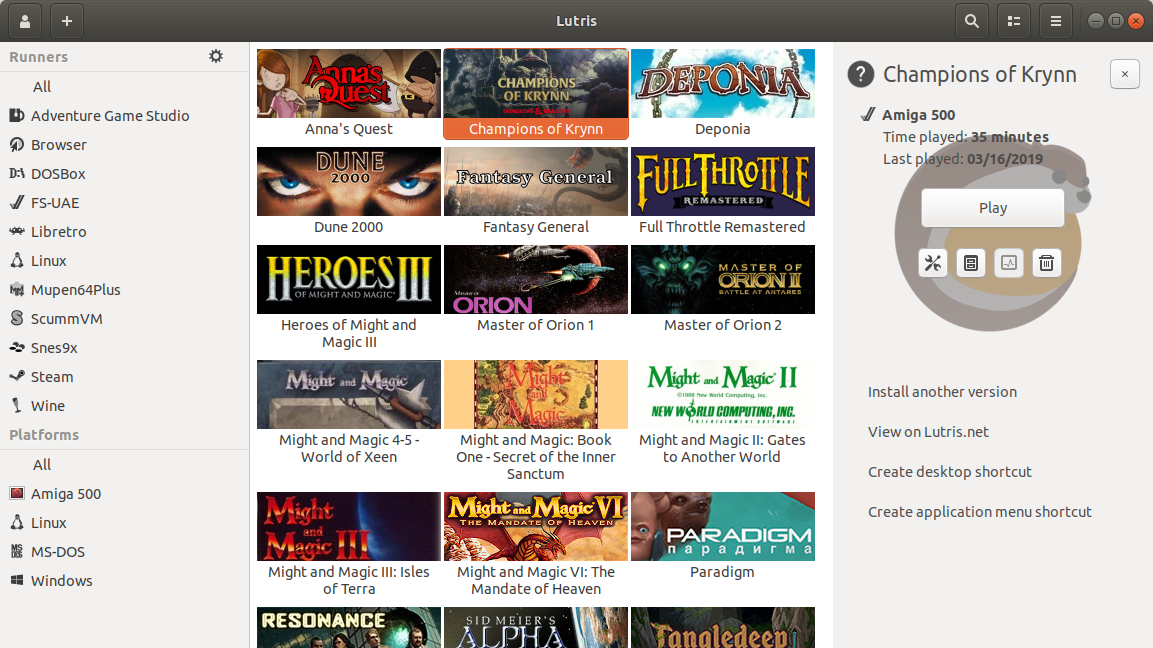

Lutris has the feel of a project that really fits into the Linux ecosystem. Open to all comers, after a few minutes of setup, you may have a gaming library that looks like this, where Linux native games live alongside games run under Wine, DOSBox, or FS-UAE (an Amiga emulator):

The Lutris user interface showing a set of games using different “runners”. (Credit: Lutris developers and various game development studios. Fair use.)

If a game isn’t in the Lutris database and not Linux-native, you may still have to go through a fair bit of trial and error, and it may not work at all. There’s less polish and more of a DIY feel to all of this: Lutris doesn’t protect you from doing things that won’t work, while a platform like Steam does its best to ensure the user always gets what they paid for.

All aspects of Lutris are open to community contributions—you can suggest changes in the game database, submit your own “runners”, or your own install scripts for specific games. And with at least a modest amount of Patreon funding, the project hopefully won’t just disappear (if it does, there’s still Phoenicis, the designated successor to PlayOnLinux).

The verdict

I’ll keep using Lutris to organize my own Linux games, and I’ve joined the project’s Patreon as well because it feels worth supporting. Whether the project is ultimately successful likely depends on whether it can grow a vibrant community of contributors: not just of runners and installers, but also of game metadata and contributions to the client.

I encountered a few rough edges using Lutris (the experience importing games you’ve installed from GOG is still fairly manual; I ran into a few 404s in the game database; the per-game preference dialogs are a bit nightmarish), but overall it’s already saved me a fair bit of time getting some Windows games to run without futzing around too much. And I’m happy to trust the judgment of the Lutris community to find the best emulator for a certain platform or game.

The database of games on Lutris.net is its own ambitious project, and it might benefit from integration with Wikidata and perhaps even use of the Wikibase software instead of its own custom change management tooling; it also currently doesn’t have a clearly stated license.

As a whole, Lutris is currently the most promising effort of its kind. If you’re a Linux gamer, I recommend taking a look at it, along with more narrowly focused projects like Lakka (a Linux distribution just for retrogaming) and the aforementioned Phoenicis.