Latest reviews

Is rudimentary consciousness a fundamental property of matter? The idea strikes many people as bizarre, because it evokes notions of self-aware household objects and tomatoes screaming in pain as they make their way into the pasta sauce. But it deserves more precise articulation and a fair hearing.

In “Galileo’s Error”, philosopher Philip Goff makes the case for this idea, known as panpsychism, for a general audience. He begins by outlining the problems with dualist mind/matter explanations (where the mind is a separate “thing” that somehow interacts with matter), and with strictly materialist explanations that neglect to offer any explanation for the quality of conscious experience.

What if those qualities are the intrinsic nature of matter itself? In this view, the human mind is continuous with the universe in which it is embedded. There’s no need to postulate “special mind stuff”, to invent deities, or to wave your hands and say “emergent property”.

Instead, in this view, subatomic particles like electrons experience change, and more complex forms of consciousness can be built up (or indeed arise) from simple ones. The qualities of human experience—the color red, the smell of coffee, a loving touch—must have their foundations in matter itself.

Of course, this is not a new idea, and many philosophies and religions have embraced forms of panpsychism. It is not even new to Western philosophy, and Goff especially cites the debates between Bertrand Russell and Arthur Eddington. This context is where the book offers what I consider to be the most succinct argument in favor of the panpsychist hypothesis (p. 134):

Eddington’s starting point is as follows:

Physical science tells us absolutely nothing about the intrinsic nature of matter.

The only thing we know about the instrinsic nature of matter is that some of it, i.e., the matter inside brains, has an intrinsic nature made up of forms of consciousness.

It is hard to really absorb these two facts, as they are diametrically opposed to the way our culture thinks about science. But if we manage to do so, it becomes apparent that the simplest hypothesis concerning the intrinsic nature of matter outside of brains is that it is continuous with the intrinsic nature of matter inside of brains, in the sense that both inside and outside of brains matter has an intrinsic nature made up of forms of consciousness.

Aurora Borealis, seen from Iceland in February 2014. The complexity of the nonliving world invites the question whether it is fully discontinuous with embodied human experiences. (Credit: Schnuffel2002. License: CC-BY-SA.)

Yet, current scientific attempts to explain consciousness rarely consider it a phenomenon that is even worth studying outside of the context of a brain. And these “explanations” (e.g., efforts to show that certain neural activity is correlated with certain conscious experiences) are at best predictions—they don’t get us much closer to understanding what conscious experience is.

Goff points the finger at Galileo Galilei for setting science on a path that is strictly quantitative, a path where any effort to explain the quality of an experience (the color red, the smell of coffee, a loving touch) is out of bounds, or at least suspect. Goff argues that to disregard these qualities is to disregard fundamental scientific facts. Indeed, no fact is as foundational and undeniable as the reality of our own conscious minds.

Panpsychism is an attractive hypothesis. Like the many-worlds interpretation of quantum mechanics, it elegantly resolves tricky questions at the very “bottom” of existence. It also has similar difficulties of testability, which could put it in the “not even wrong” realm of speculation. Perhaps, as our ability to predict conscious states increases thanks to efforts like integrated information theory, we will predict them in places where we wouldn’t expect them. Then the more difficult claim to defend may be that “mere matter” is not continuous with conscious experience.

The Verdict

Philip Goff presents a cogent and beautiful argument in defense of a thesis many “materialists” will seek to dismiss as New Age woo. But the idea that consciousness needs no rudimentary precursor in nonliving matter may itself turn out to be woo. Goff does not assert that the panpsychist hypothesis is correct—only that it should be considered seriously in our efforts to understand consciousness.

The book is strongest when it presents this core argument. Goff lost me in the last chapter, where he makes what I consider to be a very weak argument for a non-deterministic universe and the existence of free will. He argues that “free will” is the “responsiveness to rational considerations”, but it’s not clear why a deterministic brain cannot be “responsive to rational considerations”, and why determinism must be a constraint to be “freed” from. Perhaps that is a matter for another book; in any event, it seems out of place in this one.

I recommend Galileo’s Error not as any definitive answer to questions about the nature of consciousness, but as a very well-reasoned argument for expanding the Overton window of science, especially when it comes to explaining the very qualities that make life worth living.

Can a game be a place?

As the player of Firewatch, you are a man named Henry who starts a job as a lookout in Shoshone National Forest, in Wyoming. In the preamble, we learn that this is an escape from dealing with your wife’s early-onset dementia.

Your only regular human contact is by radio, with a woman named Delilah who works in another lookout tower. Delilah is your boss, and she soon gives you your first assignment: to investigate some illegal fireworks near a lake.

Your relationship with Delilah is influenced by the dialogue choices you make. Mostly, the game keeps you on rails to uncover a larger mystery. This involves a lot of walking around through beautiful landscapes, using your map and compass to find your way.

This is an exploration game—or, as some would say, a walking simulator. The biggest challenges for the player tend to be of the “how do I get from A to B” variety. Nonetheless, Firewatch manages to be immersive and at times even menacing. The game targets an adult audience—as the developers put it, it is a “video game about adults having adult conversations about adult things.”

Firewatch offers many scenic views of its version of Shoshone National Forest. (Credit: Firewatch by Campo Santo. Fair use.)

After you finish the story, you can still continue to explore Shoshone National Forest at your leisure (and collect the game’s soundtrack in a mini-game). The landscapes really are beautiful, whether you’re walking through Thunder Canyon towards the lake, admiring a sunset, or exploring the forest at night with your flashlight on.

It is a very short game, and like life itself, its story is ultimately a bit untidy. You’re unlikely to get more than 4-6 hours of play time out of it. But it is a game that is also a place, and years after playing it, you may be tempted to visit it again.

The current regular sales price for Firewatch is $20. It has repeatedly been on sale for $5, so I recommend wishlisting it and buying it at a lower price.

James Gleick is widely regarded as a masterful science writer, and for good reason. Through the 526 pages of The Information (2011), Gleick spins an accessible tale about Charles Babbages’s difference engine, about Turing machines and Maxwell’s demon, about Gödel’s incompleteness theorems and Shannon-Fano coding and Boolean algebra, all in service of illuminating a concept that may seem ineffable: information itself.

Gleick shows how complex computation and signal processing problems led to the development of information theory, which gave us ways to quantify information and to speak about the entropy of a body of text. This in turn touched countless other disciplines, and made the networked world we find ourselves in today possible. Towards the end of the book, Gleick explores the wonders of this world, including Wikipedia.

The book was written before recent debates about fake news, Twitter bot armies, and similar disinformation campaigns, but Gleick anticipated that the burdens of selecting true from false, and forgetting that which should be forgotten, would only increase.

This is a book that aims for breadth (from talking drums to telegrams, from analog computers to digital ones), not depth. If you’re looking for an introduction to information theory, look elsewhere. As a history of ideas, The Information succeeds brilliantly. Page after page, the book places a question in the reader’s mind, then addresses it; it weaves together anecdotes and facts, never overloading the reader with jargon, but not shying away from complexity.

As Gleick points out, without selecting that which matters, we end up with a Library of Babel, conceived by Argentine author Jorge Luis Borges as a library that contains all possible books of a certain length. In the libraries of the real world, this book has earned its place to give us a shared history and vocabulary for the conversations to come.

Controls are a little hard to figure out

(apologies to Randall Munroe, https://xkcd.com/2192, licensed CC BY-NC 2.5)

Although a minor tragedy in itself, since it represents a noble skill (engraving) being put towards ignoble ends (as evidenced by the intro by Hindenburg, propagandizing the Central Powers’ lost territory in the Great War; this leading to popular appetite for WWII, a much grander tragedy), each image puts one standing instantly in front of the pastoral fields and elegant churches depicted.

In How to Hide an Empire, historian Daniel Immerwahr argues that we know far too little about the history of United States beyond the contiguous states that make up the “logo map”:

As in the example above, representations of the United States often exclude Hawai’i and Alaska, to say nothing of “territories” like Puerto Rico, American Samoa, Guam, the US Virgin Islands, or the Northern Marianas. But the stories of the millions of people who live there deserve to be heard, and Immerwahr does his best to tell them.

To set the stage, Immerwahr describes the expansion of the United States from coast to coast, and the broken promises and systematic removal of native tribes that came with it. Whether tribes sought to assimilate or to fight, their land was taken; projects like the creation of the State of Sequoyah failed. Instead, US states borrowed the names of native tribes whose land was stolen to create them.

The story continues with America’s quest for bird poop—the annexation of island territory to harvest accumulated guano—and culminates in a America’s colonialism binge at the dawn of the 20th century. In the Spanish-American War, America notably “acquired” the Philippines, Guam, and Puerto Rico. The Philippine-American War that followed—a war in which Filipinos fought for liberation from American colonial rule—caused a civilian death toll in the hundreds of thousands.

The Cancer Man

But the Philippines are not the only country that resisted American colonialism. From the beginning, many Puerto Ricans have favored independence, especially in light of the overt racism they encountered in contact with visitors from the US mainland.

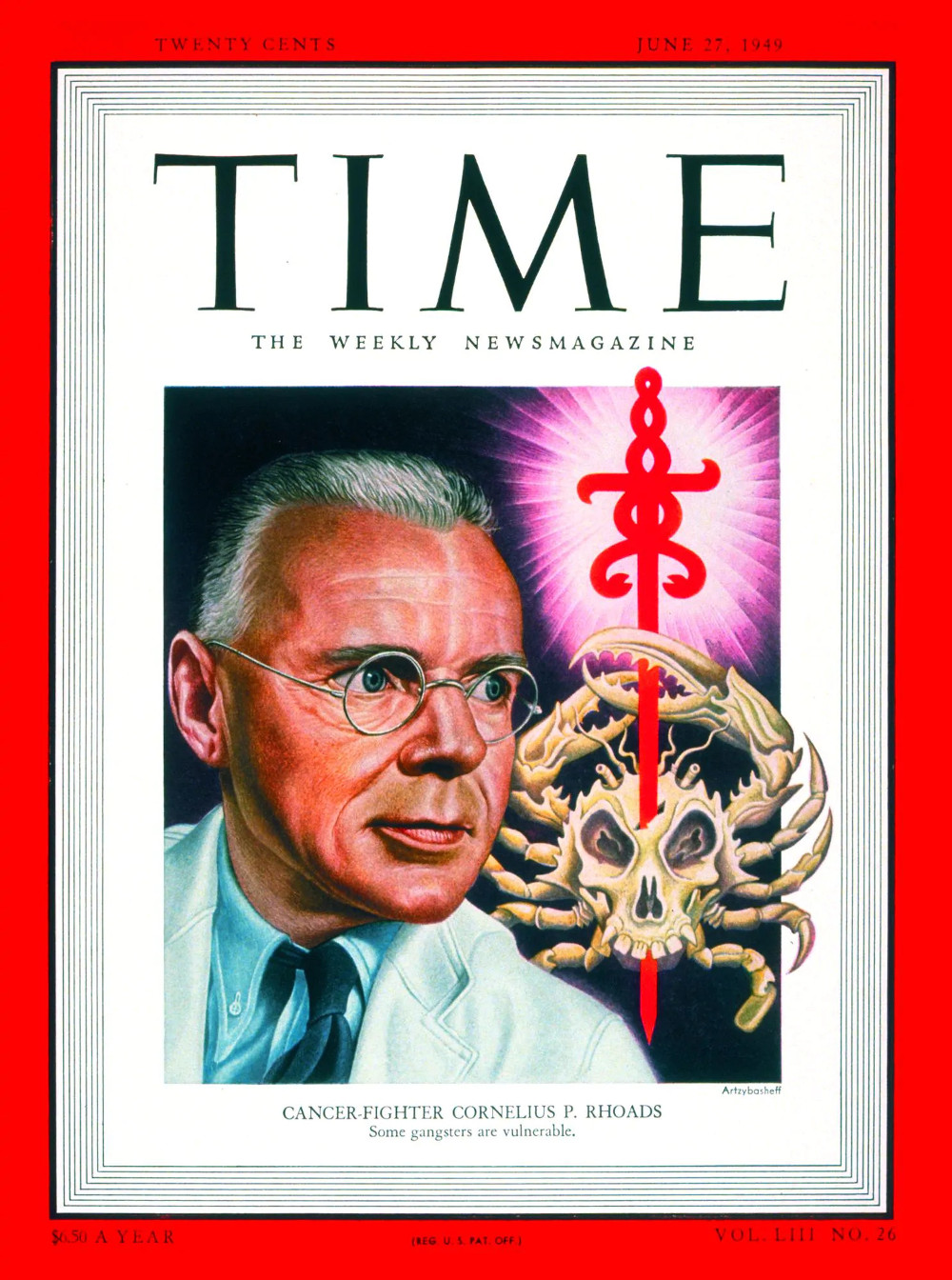

Immerwahr tells the story of Cornelius Rhoads, a US mainland pathologist who visited Puerto Rico as part of an international health effort. Rhoads not only harbored deep racial hatred for the Puerto Ricans, he bragged about murdering them:

They are even lower than Italians. What the island needs is not public health work but a tidal wave or something to totally exterminate the population. It might then be livable. I have done my best to further the process of extermination by killing off 8 and transplanting cancer into several more.

No evidence of these crimes was ever found (which does not mean that they did not take place), and Rhoads called the letter a joke. He faced no significant consequences for it, and became a celebrated cancer researcher (and an expert in chemical and biological weapons, charged with approving tests on human subjects during the war).

Time Magazine cover featuring Cornelius Rhoads, June 27, 1949. (Credit: Time Magazine. Fair use.)

The Rhoads letter was a major scandal in Puerto Rico that drove many to join its burgeoning independence movement. One of them was Oscar Collazo, who joined with another Puerto Rican nationalist in an attempt to assassinate US President Harry Truman in 1950.

Due to the historical amnesia that characterizes America’s relationship with its “territories”, it was only in 2002 that Rhoads’ name was removed from a prestigious award due to the letter in which he bragged about murdering Puerto Ricans. “And that’s how you hide an empire”, Immerwahr observes.

The Empire of Points

The later part of the book mainly deals with the question why America did not become an empire in the British mold after World War II. Instead, the US relinquished control over one colony (the Philippines, through the Treaty of Manila) and sought to establish no new colonies elsewhere. Military bases around the world—a “pointillist empire”—replaced the conventional model of control over vast swaths of territory.

Immerwahr sees multiple reasons for this change, most notably:

-

the growing rise of independence movements around the world, which made colonies an increasingly costly proposition;

-

America’s leadership in synthetics, logistics, and standardization—achieved in significant part through wartime efforts—which enabled it to project military and economic power throughout the world, without being dependent on territorial control;

-

wartime weariness of US troops, who wanted to go home, not occupy a country like the Philippines they had fought side-by-side with the Filipinos to defend.

Immerwahr concludes by examining the political and cultural impact of US military bases, and the connection between this new form of imperial power and the threat of terrorism organized from many small, well-hidden locations.

The Verdict

Immerwahr is a very talented writer, and How to Hide an Empire is full of facts about the “Greater United States” most readers are unlikely to be familiar with. While this isn’t a funny book, Immerwahr isn’t shy to use humor and the first person intermittently throughout the book, without it seeming out of place.

All of this is a potent combination, and I found the book to be a real page-turner. My only criticism is that the author, in emphasizing the role of territory (from colonies to military bases), ends up spending very little time discussing the many other ways the US has projected imperial power, from overthrowing governments to meddling in elections.

While I don’t believe for a moment that this was the author’s intent, readers unfamiliar with this larger history might come away with the impression that the territorial story is the whole story. A larger analytical frame would have served the book well, but as it is, it remains a very readable and insightful analysis of America’s relations with the people who live in the United States beyond the logo map.

Good 100% vegan place to have a decent meal. The service was very friendly and quick. The food was good.

No alcoholic beverages are available.

The short stories in this 450 page collection by Ken Liu (The Grace of Kings) span historical fiction, fantasy, and science fiction. They include:

-

the story of a woman living in a world in which souls are real, and represented by physical objects we carry around with us (the protagonist’s inconveniently manifests as an ice cube);

-

the story of an American girl in 1960s Taiwan who befriends a Chinese practitioner of the divination practice known as literomancy, and whose friendship gets caught up in the Cold War;

-

the story of a couple of who invent a method of witnessing (but not altering) historical events as they occurred, and who use it to produce modern eyewitness accounts of crimes against humanity committed by the notorious Unit 731 in China during the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937-1945).

Themes that run through many of the stories featured here include the pursuit of personal and historical truth; the balance of self-interest and societal interest; the transmission of culture and tradition through migration and trade.

Liu, who was born in China but whose parents moved the family to the United States when he was 11 years old, has done much to make Chinese speculative fiction available to Western audiences. Most notably, he translated the best-selling The Three-Body Problem into English, and has curated two anthologies of Chinese sci-fi (Invisible Planets and Broken Stars).

Many of his short stories incorporate elements of Chinese history and folklore. This makes them great jumping off points for further exploration. For example, one story about a group of Chinese gold miners coming to a town in 19th century Idaho explores the fascinating mythology surrounding Guan Yu (a general in ancient China).

Above all, I admired Ken Liu’s willingness to confront difficult themes unflinchingly. Many of the stories featured here pack quite an emotional punch, and often expose us to humanity at its worst and and its best in the same story.

While I would rate some individual stories in this volume as low as 3 stars, the best ones (including the title-giving The Paper Menagerie) are so exceptionally good that I would recommend the collection as a whole highly to any fan of speculative fiction.

OpenStreetMap, despite having “map” in its name is more than just a map, and certainly more than just a street map. It’s a collaboratively authored and edited geodatabase. You can enter anything that is objectively verifiable “on the ground” into it, and conversely you can find almost everything in it, though without any claim of accuracy, completeness or up-to-date-ness. (Though if you notice anything to be inaccurate, incomplete or out-of-date, you’re free to improve it.) The data for the complete “planet” can be freely downloaded and analyzed, or used to build your own maps, navigation, or what-have-you. There’s a whole ecosystem of third-party services, tools and derived works (such as maps) that has developed around that.

The data model is unlike the others commonly found in the GIS world, which makes analysis of OpenStreetMap data with general-purpose GIS tools cumbersome at times.

Disclosure of conflicts of interest:

I am:

- a user and contributor of OpenStreetMap

- a member of the OpenStreetMap Foundation (OSMF)

- a board member of the Swiss OpenStreetMap Association (SOSM), the Swiss local chapter of the OSMF

Ein nettes, einfach zu bedienendes aber nicht so leicht zu meisterndes Spiel für zwischendurch. Wenn ich es länger spiele, wird mein FairPhone 2 allerdings recht heiß …