Latest reviews

“The Road To Forgiveness” - By: Bill and Cindy Griffiths is a powerful true story of a couple who forgave the woman who hit and killed their daughter and mother / mother-in-law while driving drunk. It’s one of the best books I have ever read. If you are interested in powerful, true stories you should love this book.

What’s not to love? I can’t go wrong with classic hymns and my favorite singer. I absolutely love it! There are a lot of great voices in music, but none of them touch my heart more than Lauren’s voice does. I only wish there were more songs. Lauren explained that she didn’t want to put too many songs on this release because she didn’t want the majority of them to be overlooked. She wanted more attention to be paid to each individual song that’s on the release. I can understand this reasoning but I still wish there were more songs. Only 6 songs here, but a great EP by Lauren Talley.

Gladiabots is a strategy game where you program a team of robots to win battles. There is 3 different game modes, elimination, domination and collection. The single player is lengthy with many levels of increasing difficulty with the layout of the arena and enemy team varying enough to keep it interesting.

The gameplay is half programming, half watching your team do battle. The programming is easy to get started with as every thing is done visually. You layout commands with the leftmost having the most priority. As you try to make your robots behavior more specific, the visual programming becomes a hinderence and anybody whos written code will be yearning to play the game by actually programming. Watching the battles stays fairly entertaining since you can speed up or slow down to only watch the parts that show if your programming is working.

There’s definitely bugs where the game doesn’t execute the programming properly, but they’re rare enough not to impact gameplay. The game also wants you to sign into an account to share your score and will ask you to sign in after EVERY game if you don’t. The game also comes with data collection for the Unreal engine turned on. On Linux, you can see the settings in .config/unity3d/GFX47/Gladiabots/prefs. There was no notice about this either. I only happened to find it while trying to debug a bad build of the game.

<pref name="data.analyticsEnabled" type="int">1</pref>

<pref name="data.deviceStatsEnabled" type="int">1</pref>

<pref name="data.limitUserTracking" type="int">0</pref>

<pref name="data.optOut" type="int">0</pref>

<pref name="data.performanceReportingEnabled" type="int">1</pref>

<pref name="unity.cloud_userid" type="string">ZGVlOTlkNDBhYzc0NzQzNGE5NThiN2JhOThiMGYyZDk=</pref>

<pref name="unity.player_session_count" type="string">MTE=</pref>

<pref name="unity.player_sessionid" type="string">MTYxNTUyNjIwOTAyNzUzOTA3OQ==</pref>

Unplayed: Multiplayer, Collection Mode

Overall, its worth a play.

I lived in the San Francisco Bay Area from 2008 to 2015. One name that you’ll encounter sooner or later in this region of the United States is Junípero Serra: from Junipero Serra Freeway to Junipero Serra Boulevard, from schools to playgrounds, from hiking trails to the highest mountain peak in Monterey County, and of course the statues—so many statues.

Canonized as a saint in 2015, Serra was an 18th century priest and friar who founded the first Spanish missions in California. Pope Francis claimed that Serra “sought to defend the dignity of the native community, to protect it from those who had mistreated and abused it.” The missions Serra started are popular tourist attractions.

In 2004, Elias Castillo (1939-2020), a journalist and three-time Pulitzer Prize nominee, wrote an op-ed titled “The dark, terrible secret of California’s missions” that described Serra’s work in starkly different terms:

[L]ocked within the missions is a terrible truth—that they were little more than concentration camps where California’s Indians were beaten, whipped, maimed, burned, tortured and virtually exterminated by the friars.

The op-ed was well-received by others familiar with this history, and was read into the Congressional Record. This inspired Castillo to write the book A Cross of Thorns: The Enslavement of California’s Indians by the Spanish Missions (2015).

Castillo documents that Serra was a reactionary even by 18th century standards, a man who believed in witches, rejected Copernicus, practiced extreme self-flagellation, and regarded the natives of California as savages who had to be enslaved to be brought to salvation.

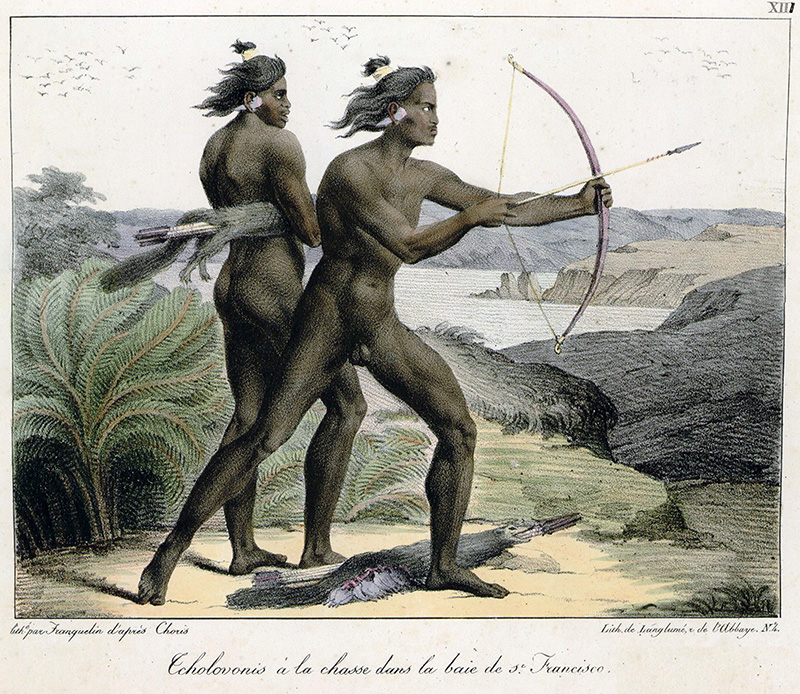

Yokuts hunting near San Francisco Bay as depicted by Russian artist Ludwig Chloris. (Public domain)

Fever dreams of salvation

Natives were herded into the missions and were forcibly returned there if they tried to flee. They lived in conditions of forced labour, and died by the thousands, often from disease which ran rampant due to the high population density. Far from “protecting” the natives, Serra resisted efforts to reduce the rate of death, to provide education or better care.

Instead of education, there was daily mass in Latin, which the natives did not understand. The Church enforced its sexual morality, separated men from women, and punished expressions of intense emotion, including grief. In a 1780 letter to Felipe de Neve, then governor of the Californias, Serra justified the use of flogging:

“That spiritual fathers should punish their sons, the Indians, with blows appears to be as old as the conquest of these kingdoms [the Americas]; so general in fact that the saints do not seem to be any exception to the rule. In the life of Saint Francis Solano … we read that, while he had a special gift from God to soften the ferocity of the most barbarous by the sweetness of his presence and words, nevertheless … when they failed to carry out his orders, he gave directions for his Indians to be whipped.”

Castillo’s book is unsparing but rigorous and well-sourced, often in the words of the people who committed these crimes or witnessed them. The many dedications to Serra in California are honoring a mass murderer. His canonization will forever taint the record of Pope Francis, who is often celebrated as a reformer.

In the wake of calls for racial justice in 2020, this history is becoming more widely known, and the first Serra statues are being removed. The myth of the friendly California missions has no place in the 21st century, and Castillo’s book should help us all to put it to rest.

Additional reading

-

Junípero Serra’s brutal story in spotlight as pope prepares for canonisation

The Guardian, September 23, 2015 -

Junipero Serra was a brutal colonialist. So why did Pope Francis just make him a saint?

Vox, September 24, 2015 -

‘By Their Fruit They Will Be Known’: Junipero Serra as Indian Killer

Indian Country Today, October 14, 2015 -

Sainthood of Junípero Serra Reopens Wounds of Colonialism in California

New York Times, September 29, 2015

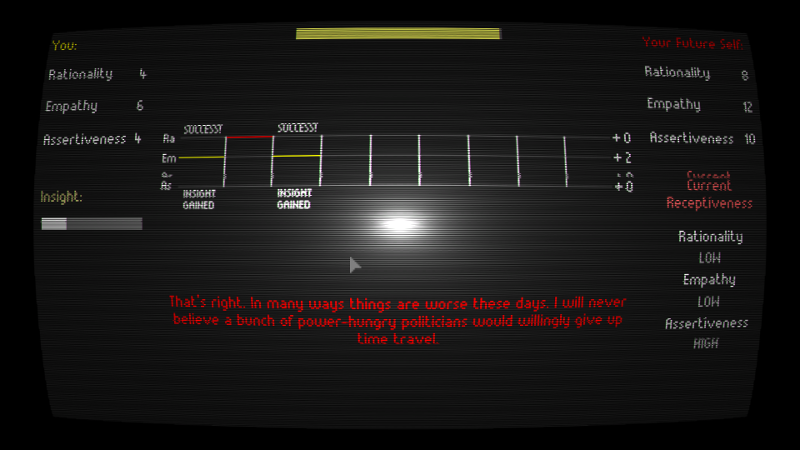

Your Future Self is an interactive story developed by Contortionist Games, which as of this writing is one developer, Andrew Hirst, based in Sheffield, UK. The game presents itself in a CRT aesthetic with many flicker effects, similar to Pony Island.

The premise is that you’re stuck in a time looping bubble with your future self and have to convince them not to commit an act that will kill thousands of people, but which your future self clearly considered justifiable. Every dialog choice can succeed or fail. If you ultimately don’t succeed, the loop starts again.

As you pick from different strategies to engage with “yourself”, the story unfolds. You can’t pick the exact words you want to say to yourself—your choices are always to be rational, empathetic, or assertive, and the game decides what that means in a given context.

There’s a light RPG-like mechanic at play here, where your “skill” at being rational, empathetic, or assertive is measured against your future self’s skills and receptivity in those areas. If you turned on “helper mode” on the start screen, the game shows you the likelihood that a given choice will succeed.

The success or failure of your attempts to persuade your future self is visualized, and is subject to a simple RPG-like mechanic. The CRT scanline effect, curved screen, and center glare are in-game visuals. (Credit: Contortionist Games. Fair use.)

There are, of course, additional layers to the story, and the game employs intense visual effects to keep things interesting. It also has an excellent chiptune soundtrack. Check out Rebels to the Rescue and Your Future Self (Remix).

The time loop mechanic can get a bit tedious if you have to click through the same loop a couple of times to find the right answers—in retrospect I think I would have enjoyed the game more if I had enabled “Helper mode”. The story was interesting enough to keep me engaged until the ending (I think I played for about 1-2 hours).

I’d give it 4 stars—the game mechanics and story aren’t perfect, but the excellent soundtrack and atmosphere make up for most of the game’s weaknesses.

The liberal Western narrative of the Cold War is that a flawed but well intentioned democracy (the United States) prevailed against a tyrannical regime that sought to spread its ideology throughout the world (the Soviet Union). The rest of the world is assigned bit parts in tales of proxy wars and covert ops between the superpowers.

In The Jakarta Method, journalist Vincent Bevins reveals a much darker story of the Cold War, one in which Third World nations sought independence from colonial rule and from post-colonial imperial domination by any superpower, and in which the United States and its allies countered such efforts, in part, through an international program of mass murder.

As the book’s title suggests, this history is centered on events in Indonesia, which is the 4th most populous nation on Earth today. After achieving its independence from the Dutch (whose colonial rule had left the country with a literacy rate of less than 10%), the new country’s first president, Sukarno, sought to build alliances with other Third World nations and organized the historic Bandung Conference in 1955.

A template for mass murder

Sukarno was not a communist, but he tolerated the Communist Party as one of multiple constituencies he unified under his increasingly authoritarian rule. The United States grew impatient with Sukarno’s anti-imperialism, and supported staunchly anti-communist military men who could replace him.

Eventually, one such man, Suharto, used the chaos of a failed coup attempt by other members of the military (of which he had foreknowledge) as a pretext to take power. He blamed the communists and implemented a mass murder program that killed a vast number of human beings, with estimates ranging from 500,000 victims on the low end to 2-3 million on the high end.

Alleged young communists detained by Indonesian troops in October 1965. (Credit: Associated Press. Fair use.)

The US did not simply tolerate this campaign; it provided training and support to anti-communists in the Indonesian military, and even supplied kill lists which were used to hunt down and murder thousands, as the Washington Post reported in 1990:

For the first time, the officials are acknowledging that they systematically compiled comprehensive lists of communist operatives, from the top echelons down to village cadres in Indonesia, the world’s fifth most populous nation. As many as 5,000 names were furnished over a period of months to the army there, and the Americans later checked off the names of those who had been killed or captured, according to the former U.S. officials.

Unlike other atrocities of the 20th century, this one remains little-known in the Western world, for obvious reasons: history is written by those who prevailed. As Bevins shows, the slaughter became a template for mass murder programs elsewhere, including in Latin America.

Before those programs began under authoritarian regimes in countries like Chile, Argentina, and Brazil, the word “Jakarta” itself was employed as a threat. Leftists and fanatical anti-communists alike knew all too well what it meant: mass murder at an unimaginable scale. Suharto had made Indonesia’s capital synonymous not with Third World emancipation, but with exterminating the political left.

Making the world safe for capitalism

The narrative of anti-communism is that all movements calling themselves socialist or communist ultimately become tyrannical, justifying the absolutist stance that the United States took in the Cold War. But the US supported murderous regimes like Suharto’s, while forcefully opposing emancipatory politics by Third World countries—no matter how democratic.

By replicating the Jakarta method around the world, the US and its allies destroyed the possibility of a moderate, democratic path to political and economic emancipation for Third World countries. The “friendly dictators” installed to exterminate the left frequently brought ruin for the rest of society, as well. Besides slaughtering hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of his own people, Indonesia’s Suharto embezzled up to $35 billion; in 2004, Transparency International ranked him as the world’s most self-enriching leader of the previous two decades.

The Jakarta Method is not a defense of communism as it existed in the 20th century. Bevins promotes no ideology and refrains from hyperbole or polemic; he simply recounts the facts, supported by the personal stories of survivors from around the world. If anything, given the secrecy of the programs Bevins writes about, many chapters in this dark history likely are yet to be illuminated.

The book reveals that the Cold War cannot be understood without the stories of the millions of people who fought for a better tomorrow, and whose lives were brutally extinguished to bequeath us the world we live in today. Not because of a choice between a greater and a lesser evil, as the liberal Cold War narrative would have us believe, but because of actions which were unspeakably evil in their own right.

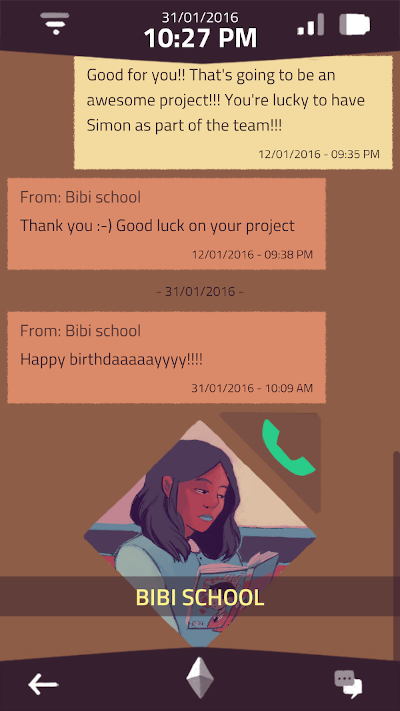

You get to browse websites, read IMs and emails and explore apps, all of which reveal layers of the game’s story. (Credit: Accidental Queens / Dear Villagers. Fair use.) Many games incorporate phones you can interact with into the game; in A Normal Lost Phone, the phone is the game. With little introduction, you get to snoop around the apps and messages stored in a lost phone that supposedly belongs to a kid named Sam who just celebrated their 18th birthday.

You discover who Sam appears to be to their friends and family; as you peel away layers of clues (“which number is the password to this app?”), you also discover new layers to Sam’s story. The story is engaging and handles mature themes of tolerance and identity well, but it is a bit predictable. It’s a short game (1-3 hours, depending on how much time you spend reading every bit of flavor text).

There’s some great artwork to discover, and a nice soundtrack that’s accessible through the phone’s music player.

It’s hard to categorize A Normal Lost Phone, but if you enjoy story-based games like Gone Home that progress quickly with very light puzzles, there’s a good chance you’ll enjoy this one, too. 3.5 stars, rated up because of the high quality art and music and the smooth interface.

Daedalic Entertainment made its name with games like Anna’s Quest and the Deponia series, which are helping to keep the genre of 2D point and click adventures alive. Since then, other developers (e.g., Dontnod with the Life is Strange franchise) have shown that it is possible to translate the exploratory appeal and rich narratives of the genre into beautiful 3D worlds.

State of Mind (2018) is one of Daedalic’s entrants into the 3D adventure genre. Set in the year 2048, it’s primarily told from the perspective of two individuals—Richard Nolan and Adam Newman—who grapple with the trauma of a recent accident, and who find that their lives are deeply connected.

The story that unfolds explores transhumanist themes like strong AI and mind uploading, but it remains grounded in a narrative about Richard Nolan’s relationship with Adam, with his own family, and with a lover.

Protagonist Richard Nolan and his household robot Simon in Richard’s Berlin apartment (Credit: Daedalic Entertainment. Fair use.)

In many parts of the game, the player explores their surroundings (e.g., Richard’s and Adam’s respective futuristic apartments; the gritty Berlin neighborhood where Richard lives, etc.), with limited choices and trivial puzzles. Occasionally, the game throws in a trickier puzzle or a mini-game.

In one of those mini-games, for example, you must navigate a drone through a building’s maintenance shafts in order to listen in on a conversation that happens in another room, without being detected by other drones. If you fail, you get to retry until you succeed.

While State of Mind offers some choices in dialogs, they are fairly inconsequential until the final stage of the game. Then, the player is given a choice between different endings, but even the impact of those choices on the final scenes of the game is a bit underwhelming.

What makes the game work, in part, is that it’s gorgeous. The low poly design of the game’s characters takes some getting used to, but the world they inhabit is rich in detail and imagination.

In one memorable scene, Adam Newman meets his wife on the location of an Augmented Reality art installation, where the game lets you draw with light and sound in the world around you. This scene is just there, and it’s up to the player whether they choose to explore it for its own sake or not.

The Verdict

The story of State of Mind is engaging but derivative, and the execution quality of the game as a whole is mixed (e.g., limited choices, mini-games that can be a bit tedious). Parts of its world are a joy to explore, and the game offers about 10-20 hours worth of generally rewarding play. The native Linux version worked beautifully for me.

I appreciated the game’s willingness to tackle adult themes, the lack of moral finger-wagging, and the deep flaws of its main characters. I found the voice acting not as stellar as, say, Life is Strange, but Doug Cockle (who voices Geralt von Rivia in the Witcher games) pulls you in as Richard Nolan, even if you end up hating him.

While the game is only 2 years old, you’ll now find it on sale regularly for 5 USD or less. At that price, you won’t have any regrets about paying a visit to its morally ambiguous world and the flawed beings that inhabit it.

If It Bleeds by Stephen King advertises itself as containing “four new novellas”, but I would really characterize it as one novella supported by three stories.

The heart of the book is “If It Bleeds” itself, which stars Holly Gibney, an important character from several of King’s most recent books (Mr. Mercedes, Finders Keepers, End of Watch, and The Outsider). After the events of The Outsider, Holly Gibney faces an evil force of a similar nature—but this time, she tries to go it alone. It’s an engaging tale that never overstays its welcome, but I would recommend reading The Outsider first (reviews).

The other stories in the book would make good Twilight Zone episodes. The first one, “Mr. Harrigan’s Phone”, would fit better in Jordan Peele’s reboot than in Rod Serling’s original. It’s about a boy’s friendship with a wealthy old man, a friendship that ultimately takes on a supernatural character. King uses the story to offer his own social commentary on the effects of smartphones, disguised in the words of a cynical old man. Overall I found it the weakest story in the volume.

The second story, “The Life of Chuck”, is told in three acts (ordered in reverse) and describes the impact of a seemingly ordinary man named Charles Krantz on the world around him—starting at a time when the whole world seems to be ending in a series of apocalyptic catastrophes.

The third story, “Rat”, is about a writer who has been struggling for his whole life to finish a novel. When inspiration strikes, he seeks out the isolation of a “basic no-frills cabin in the Maine woods” he inherited from his father, to focus on the novel without the distractions of family and social demands. Soon the isolation, coupled with an illness, starts to play tricks on his mind—or does it?

King’s constant readers can’t go wrong with If It Bleeds; those new to his work looking for recent horror novellas that pack a punch should consider picking up King’s Full Dark, No Stars (2010) instead.

According to the Oxford dictionary, faith is the “complete trust or confidence in someone or something” or the “strong belief in God or in the doctrines of a religion, based on spiritual apprehension rather than proof.” According to philosopher Martin Hägglund, we should all have it—but we should base it in a belief in this world, not in an afterlife.

The core argument of This Life: Secular Faith and Spiritual Freedom is that eternity is overrated. In fact, Hägglund claims, the religious idea of eternal life is indistinguishable from death. It is only because our lives are finite, because we may suffer horrible losses, that we can set meaningful goals for ourselves in this life.

We are striving creatures that must maintain ourselves, and our lives are only intelligible (to pick one of Hägglund’s favorite terms) with our finitude in mind, not as a limitation, but as a fundamental condition of the things we value:

The possibility of being touched is inseparable from the perils of being wounded, and exposure to loss is part of the experience of rapture. (p. 89-90, emphasis original)

All morality, in Hägglund’s view, must be grounded in our care for one another in this life. When we seek our grounding in religious promises of salvation, we implicitly place this promise above those promises that we make to each other:

If your care for another person is based on religious faith, you will cease to care about her if you lose your religious faith and thereby reveal that you never cared about her as an end in herself. (p. 10)

Hägglund engages with the theology of Augustine of Hippo, especially to bolster the critique of “eternal life” (Augustine’s eternity does indeed sound quite a lot like oblivion). He also comments at length on the biblical Binding of Isaac, and on Søren Kierkegaard’s interpretation of that story. Where Kierkegaard sees exemplary faith, Hägglund sees the dangers of fanaticism. Buddhism is not spared—nirvana is just another word for oblivion.

In This Life, we still need faith, because we must invest ourselves in people and causes whose outcome is never certain. It is this kind of commitment without certainty that Hägglund describes as secular faith.

If we are committed to this life, Hägglund says we also must commit ourselves to increasing what he calls our spiritual freedom—essentially the time freely available for any self-expression that matters to us, through work, art, or otherwise. No such commitment is valued in a capitalist economy, which places human ingenuity in the service of profit, not in the service of shared human goals. That’s why the robots take our jobs instead of improving our lives.

In his critique of capitalism, Hägglund relies heavily on Karl Marx. While affirming democracy as an essential core of any new political order, Hägglund’s vision of democratic socialism goes well beyond redistribution of wealth—he argues for sharing in the means of production, and remaking our society to maximize our freedom.

Hägglund criticizes any view of individual freedom that treats it as if it could be separated from the society in which we live:

Freedom cannot be reduced to an individual achievement since both how much free time we have and what we are able to do with our free time depends on how we organize our society. (p. 315)

In Hägglund’s view, a true commitment to (and faith in) our life together gives a critique of religion its real potency:

If we merely criticized religious beliefs as Illusions without being committed to overcoming forms of social injustice that motivate these Illusions a critique of religion would be empty and patronizing. (p. 330)

The Verdict

Hägglund’s book left me with three frustrations:

-

While I found the argument persuasive that religious promises of eternity are indistinguishable from oblivion, I also found it repetitive and tedious. Hägglund says the same thing—that our lives can only be understood in light of their finite nature—many times over.

The cosmos is more interesting than Hägglund gives it credit for. How does consciousness arise, and what defines a being—their consciousness or their memory? If an eternal being forgets its experience in whole or in part, is it still eternal? If we live in a multiverse with an infinite number of universes, how can we relate our successes and failures, our victories and losses, to these infinite possibilities? These are the kinds of questions This Life does not grapple with.

As a secular humanist and atheist, I have no faith in any promises of an afterlife, and I appreciate Hägglund’s willingness to engage in a radical critique of such promises. But I also try to retain a sense of wonder about the infinite and the very, very vast. Moreover, I believe such wonder can make us more resilient when we are faced with tragic loss. -

Hägglund’s critique of capitalism feels similarly unimaginative. He primarily re-frames Marx’s 19th century analysis in his own philosophical terms, but other than repeatedly emphasizing the importance of democracy, he does not make a cogent argument how past catastrophic failures of communism can be avoided in future.

Hägglund lays out three principles for democratic socialism, one of which is “that the means of production are collectively owned and cannot be used for the sake of profit.” But what is required in practice to uphold such a principle? What happens to the first person in this democratic society who starts keeping the “means of production” for themselves?

I am more persuaded by the more modern arguments in favor of transforming capitalism towards a solidarity economy, where cooperation is rewarded through structures and incentives. See, for example, the book “Humanizing the Economy”, which examines such examples—you won’t find them in Hägglund’s book.

I agree with Hägglund that redistribution of wealth is not enough. But a democratic socialism fit for the 21st century needs to be a bit more responsive to what we’ve learned since the 19th. -

Finally, I see very little reason for reframing secular humanism in terms of “secular faith” or living a “spiritual life”. These terms may appeal to a certain audience, but for those who have explicitly rejected faith, they hold little value.

When Hägglund talks about “keeping faith” with our commitments (a marriage, a friendship, a purpose), he is using religious language where non-religious language will do just fine. It is true that we face uncertainty in all our life commitments. It is also true that we continuously re-examine those life commitments based on our lived experience.

We abandon projects that are failing. We end marriages that don’t work. We lose friendships because our lives drift apart. When a commitment doesn’t make sense anymore, we should end it—and that kind of responsiveness to evidence is the opposite of faith.

This Life may help broaden the appeal of secular humanism, but it diminishes it by re-framing it in religious terms. It offers a useful critique of capitalism, but it fails to advance the discussion of how to replace it. It is not afraid to challenge ideas of holy oblivion, but it does not recognize the hope and inspiration we can take from the cosmos we find ourselves in.

The journey This Life takes the reader on is an important one. I’m just not sold on the destination.