Latest reviews

The Princess Bride was only a moderate success at the box office, but since its release in 1987, it has become a cult classic. Its lovable characters left an indelible impression on many, and the film has bestowed us several pop culture quotes and assorted GIFs, e.g.:

-

“Inconceivable!” — “You keep using that word. I do not think it means what you think it means.“

-

“Hello, my name is Inigo Montoya. You killed my father. Prepare to die.“

-

“You seem a decent fellow… I hate to kill you. “ — “You seem a decent fellow… I hate to die. “

This one’s a classic, too:

The movie is based on a book, and if William Goldman is to believed, that book was written by a Florinese author named S. Morgenstern a long time ago, re-released in translated and abridged form by Goldman in 1973. Of course, he is most definitely not to be believed—but the fake origin story adds a charming narrative layer to Goldman’s novel.

At its heart, The Princess Bride is a comedic story of true love between Buttercup, a farmer’s daughter, and Westley, a farmhand. Their love is imperiled by the machinations of one Prince Humperdinck and his sadistic right-hand man, Count Rugen. Along the way, Buttercup and Westley cross paths with Inigo Montoya (a Spanish master swordsman), Fezzik (a Turkish giant), and Vizzini (a Sicilian criminal genius)

Compared with the movie, the book gives Inigo a proper backstory, helping lend emotional weight to the final confrontation between Inigo and the six-fingered man who killed his father. We also learn more about Fezzik the giant, although it’s a fairly worn out tale (the sweet, gentle giant who reluctantly learns how to use his strength).

But what of Buttercup? While she gets to boss Westley around for a bit in the beginning, she is quickly reduced to the traditional traits of princesses: beauty and devotion. One can argue that the book takes its stereotypes to such ridiculousness that they lose normative power, but that argument only goes so far.

Still, what saves The Princess Bride from becoming conventional and boring is its sense of humor. From the Rodents of Unusual Size (R.O.U.S.) to the Zoo of Death, from Miracle Max and his questionable cures to Goldman’s tall tales about S. Morgenstern, the book is an entertaining page-turner.

Modern editions include the first chapter of Buttercup’s Baby, a sequel to The Princess Bride that was unfortunately never completed (Goldman died in 2018). It gives us a small glimpse of further adventures that could have been.

Not everyone will adore The Princess Bride as much as its many devoted fans do, but if you are a lover of adventure and comedy, it may well earn a special place on your bookshelf and in your heart, or the heart of a smaller human you read it to.

After a long, bloody history of colonial rule, Britain finally abandoned in the Indian subcontinent in 1947. Against significant opposition, the Brits negotiated the partition of India into India and Pakistan. This led to a refugee crisis, mass violence, and the deaths of between 200,000 and 2 million human beings. The resulting so-called “Muslim homeland” of Pakistan was not the nation we know today, but a country divided into West Pakistan and East Pakistan, with a whole lot of India between them:

Partition resulted in a bizarre post-colonial map, with a divided “Muslim homeland” (home to millions of non-Muslims) bordering India. Credit: BBC. Fair use.

Less than 30 years later, the fiction of East Pakistan collapsed in genocide and war. After an election that would have shifted the balance of power to the Awami League, which sought independence for the East, Pakistan responded by abandoning its brief experiment with democracy and sent in its troops from the West. They unleashed atrocities that killed between 300,000 and 3 million people (often with weapons Pakistan had bought from the US). Hindus were singled out for extermination and expulsion, making this a genocide by every definition.

This spurred a refugee crisis that overwhelmed neighboring India, giving it cause and pretext to arm its Bengali neighbors and, ultimately, help them fight the Bangladesh Liberation War. The country of Bangladesh was born from the blood and the ashes. Brutal revenge killings against anyone who was seen as a collaborator with the Pakistani military followed.

The Blood Telegram by Gary J. Bass tells this story with special focus on the actions of US foreign policy decision-makers, chiefly Richard Nixon and Henry Kissinger. Nixon had developed a personal friendship with Pakistan’s dictator, Yahya Khan, and sought to preserve a strategic alliance with Pakistan, in part in order to use Yahya as a secret diplomatic channel in the planned opening of relations with the People’s Republic of China.

Bass uses the Nixon White House tapes, interviews, and countless historical documents to reconstruct a detailed picture of how the US government and its foreign policy apparatus responded to the genocide as it unfolded in East Pakistan.

A very clear picture emerges: Nixon and Kissinger did not care about the genocide, declined to put any pressure on Yahya to stop it, and bullied internal dissenters into silence. They refused to stop all pending arms transfers, and when the Bangladesh Liberation War started, they illegally used third countries (Iran, still ruled by the US-backed Shah, and Jordan) to funnel weapons to Pakistan. They tried to draw China more deeply into the conflict, and threatened India with an aircraft carrier.

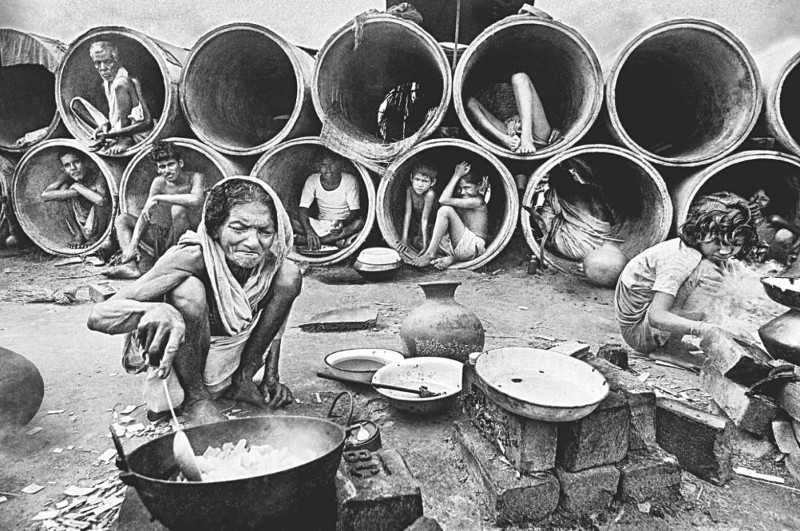

“Salt Lake” refugee camp in Calcutta. Millions of refugees from the genocide overwhelmed India, a country already struggling with extreme poverty. (Credit: Raghu Rai. Fair use.)

“Our government has failed”

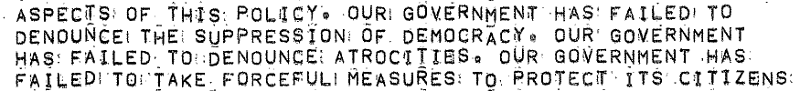

The “Blood Telegram” of the title was sent by Archer Blood, then US Consul General in Dacca soon after the genocide started. The diplomatic staff were witnessing the mass killings firsthand, and after repeatedly warning their superiors about the unfolding crisis, they prepared a confidential dissent statement to express their deep concern with US foreign policy.

Excerpt from the “Blood Telegram” itself, April 6, 1971.

Blood did not sign the statement, but he expressed his agreement with its contents. For his dissent, Nixon and Kissinger recalled him to the State Department’s personnel office back in DC.

Even in isolation, any defense of US foreign policy towards the 1971 genocide does not withstand scrutiny. There was no “pragmatism” here, because the US did not pragmatically push for political stability when it had the opportunity to, nor did it pragmatically choose one of the many alternatives for creating an opening with China.

Bass shows the role of emotion and prejudice in decision-making. Kissinger, who cultivates an image of a wise statesman and master of “realpolitik”, was ranting and raving about the Indians along with Nixon, and the two of them outdid each other with bizarre analogies (Yahya was “Lincoln”, the Indians were “Nazis”, Pakistan was being “raped” by India). The best that can be said about their actions is that they provided (inadequate) humanitarian aid to India in a “too little, too late” attempt to avert or delay war.

One fascinating aspect of this history is the role of the Soviet Union. An authoritarian regime, it allied itself with democratic India and supported the liberation of Bangladesh. In a complete reversal of Cold War stereotypes, here it was the Soviets who defended democracy and human rights, for their own reasons that were far more cool and pragmatic than Nixon’s emotional allegiance to a military dictatorship that pursued a course of self-destruction.

An incomplete portrait

The Blood Telegram is neither a full accounting of the events that led to the creation of Bangladesh, nor a comprehensive view of America’s foreign policy under Richard Nixon and Henry Kissinger. While Bass hints at other evils—the brutal escalation of the Vietnam War, the carpet-bombing of Cambodia, the installation of a murderous dictatorship in Chile—he focuses on his central thesis: different choices could have prevented or slowed the killing in East Pakistan.

Bass makes this case with commendable scholarly rigor, but an obsessive level of detail about the Nixon/Kissinger dynamic takes up space that could have been used to place these events in their larger context. In isolation, America’s complicity in the genocide in East Pakistan may seem like a historical abnormality. In the larger history of US foreign policy, which is littered with millions of avoidable deaths, it’s not the specific behavior of Nixon and Kissinger that was historically abnormal, but the vocal dissent represented by the Blood Telegram.

Homo sapiens spent 99% of its existence on Earth in a hunter-gatherer lifestyle. So it’s perhaps no surprise that the game Don’t Starve, where you gather twigs and berries and set traps for rabbits, has an incredibly addictive quality to it. Released by Canadian indie studio Klei Entertainment in 2013, Don’t Starve has since spawned a multiplayer variant and a fair amount of downloadable content (DLC).

The base game will keep you busy for a while. It combines roguelike elements (procedurally generated worlds) with crafting, farming, a day/night cycle, seasons, and many different ways to die.

For starters, there’s darkness itself: if you spend more than a few seconds in total darkness, you will die from mysterious causes. If you don’t eat, you starve (duh!). If you don’t find ways to preserve your food, it slowly spoils in your inventory. If you don’t sleep, you slowly go insane. Every few nights you get attacked by ever-growing packs of hounds. During winter, you may freeze to death. Or you could get killed by bees, frogs, spiders, giant birds, tentacles, pengulls, beefalo, did I mention tentacles, and myriad other creatures.

A small walled camp with a tamed baby beefalo, farms, and drying racks for meat. (Credit: Klei Entertainment. Fair use.)

Still, after a few early deaths (and maybe after reading a few spoilers online), the game becomes surprisingly chill. Most creatures don’t attack unless provoked or approached, and you can craft yourself a little fortress and prepare a good defense against the regular hound attacks. Just as you’ve gotten the hang of it, Don’t Starve lures you into Adventure Mode, where you get to face off against the game’s antagonist, a pinstripe-wearing half-demon named Maxwell, in extra-hard challenge worlds.

You also quickly unlock most of the game’s playable characters, all with different skills and weaknesses. So far I’ve mostly played as Wilson, but I look forward to playing as creepy-girl-with-the-dead-sister Wendy or as Woodie, a lumberjack with a talking axe.

As you may have guessed by now, the game does not go for realism: its art style is influenced by Tim Burton, and its world is littered with magical items and the means to craft them. You will also encounter sentient pig creatures living in little houses, who can be tamed to do your bidding, or brutally killed and turned into football helmets and meat.

Procedural generation works best if it creates worlds that feel like places worth visiting, not just empty rooms and corridors. Each game world in Don’t Starve is a place to be navigated: where are the rocks to mine, the berries to harvest, the trees to fell? As you survive days and nights, your brain starts to map out these game worlds just like it does any other place.

The Verdict

Don’t Starve is a masterclass in game design, with excellent controls and menus that make the complexity of its mechanics a joy to manage. While I didn’t find the artwork very appealing at first, it quickly grew on me, thanks to lighting and sound effects, cute animations and funny dialogs, and the living rhythm of the game’s plants and creatures.

The game has its dull moments where you just gather resources or wait for night to turn into day. But these quiet minutes also present opportunities to organize your inventory, to craft a needed item, or to plan out the next day.

Don’t Starve is available for virtually every platform now (including Linux, Android, and Nintendo Switch), and you can regularly find the Steam or GOG version on sale for $5 or less. Developer Klei Entertainment also deserves credit for publicly renouncing “crunch time” and pledging not to overwork its developers. I highly recommend the game, and I look forward to checking out Klei’s other titles, nearly all of which have received very favorable reviews.

I’m a big fan of point and click adventures (think The Secret of Monkey Island), a genre that’s frequently been declared dead but that is in fact thriving thanks to crowdfunded major efforts like Broken Age (reviews) and Thimbleweed Park (reviews), smaller studios like Wadjet Eye, and releases by even smaller teams or solo developers. Clam Man is very much the latter, developed by “Team Clam” which appears to comprise three collaborators.

The game is set in a world dominated by anthropomorphic aquatic creatures. You play Clam Man, an ordinary bloke working as a junior sales representative at Snacky Bay Prime Mayonnaise. After Clam Man gets fired for no apparent reason by his crab boss, he begins to uncover a larger mayo-centered conspiracy. Does it go all the way to the top? Mr. Man will try to find out.

Not all is as it seems at Snacky Bay Prime Mayonnaise. (Credit: Team Clam. Fair use.)

It’s all ridiculous, of course, but some of the jokes are quite funny, and the minimalist hand-drawn art is often very charming. This is only a two hour game, the mouse controls are a bit frustrating, and the writing and artwork don’t quite hold up throughout the short playtime, so the current asking price of $10 is a bit high.

If you already own the game from The Mother of All Bundles, or if you can get it for $5 or less, you’re unlikely to regret your visit to Snacky Bay. Team Clam is certainly one indie developer to keep an eye on.

Der Campingplatz lädt durch eine vielzahl positiver Eigenschaften zum längeren Verweilen ein.

Auch der Aufenthalt auf den angenehm gelegenen Übernachtungsstellplätzen ist sicherlich lohnenswert.

Der Aufbau des Platzes ist terassenförmig. Es gibt Komfort(stell)plätze mit ausreichend Platz um nicht mit den Nachbarn Tür an Tür zu sitzen.

Das Restaurant am Platz bietet eine angenehme Auswahl an gut bürgerlichen Gerichten, die gut umgesetzt sind und ebenso schmecken.

Für Kinder gibt es einige Angebote, täglich wechselnd, wie z.b. Ponyreiten oder auch eine kleine “Wanderung” mit Fackeln.

Wir waren mit unserem einjährigen Kind im Wohnmobil an einem Komfortstellplatz.

Zu unserem Bedauern wurde das Plantschbecken entgegen anderer Aussage, nicht in Betrieb genommen. So konnten wir mit unserem Kind nur ins Schwimmbecken was natürlich nicht denselben Spaß bedeutet. Zum Abkühlen hat es gereicht.

Der Kiosk hat zwar feste Öffnungszeiten, diese werden jedoch nicht (immer) eingehalten. An einem heißen Sonntag mussten wir zwei Stunden länger warten um etwas trinkbares zu bekommen.

Gestört haben uns die späten Ruhezeiten, ab 23 Uhr, die das ein oder andere Mal durch Nachbarn genutzt wurden, sowie das ein Dauercamper uns mit seinem tollen Pizzaoffen einen Nachmittag und Abend lang eingeräuchert hat, da dieser mit offenem Feuer betrieben wird. Unser Kind wurde während des Mittags und abendlichen Schlafs entsprechend eingeräuchert, da es zu warm war um die Fenster im Wohmobil geschlossen zu lassen.

Der Platz ist aus unserer Sicht gut geeignet für “Übernachtungsgäste” und Personen mit älteren Kindern oder ohne Kinder, die keine Ruhe brauchen.

Im Jahr 2061 droht die Sonne zu einem roten Riesen zu werden. In 100 Jahren wird es die Erde nicht mehr geben und in 300 Jahren wird das Sonnensystem nicht mehr da sein. Es gibt eine Erdregierung, die beschliesst die Erde mit Raketen in das 4.2 Lichtjahre entferne Alpha Centauri Sternensystem zu bringen.

A depiciton of scenes with minimalist graphics and some objects in places/situations that are out of the ordinary. The only interaction happens at pauses where you are forced to click flashing objects to move to the next segment.

I made it through 3 uninspiring scenes before tapping out. I found the style interesting, but it didn’t go anywhere. The scenes aren’t pretty enough to be appreciated solely for beauty and I found no insight in the places forms were changed from the ordinary.

A Short Hike lets you explore the colorful, pixelated world of Hawk Peak Provincial Park in the role of a vacationing anthropomorphic bird named Claire. Your mission, should you choose to accept it, is to make it to the top of Hawk Peak, ostensibly in search of cell phone reception.

As you make your way through the park, you meet a diverse cast of animal characters. Some offer you side quests, others are simply pursuing their own adventures in the park. It’s up to you whether you want to accept any of these quests, but if you want to make it to the peak, you’ll need to at least obtain a few golden feathers, which allow you to climb the distance.

The game doesn’t end after you reach the peak. There are treasures to be found, hats to be purchased, fish to be caught, and co-operative games of beachstickball to be played. And it’s fun to explore. In spite of the intentionally low resolution graphics, when you sky-dive from the top of a hill, A Short Hike manages to convey a real sense of velocity and freedom.

You can fly, dive, swim, climb, walk, and run. (Credit: Adam Robinson-Yu. Fair use.)

You can’t die in this world, or screw up in any irreversible way. Nor does the game offer the endless grind of more complex farming, fishing, and crafting games. You can rush through the game, or spend a few hours with it, but after that, you’ll likely be done with it—at least until you feel like paying another visit to the park.

If you’re looking for a game to challenge your reflexes or your logic, this ain’t it. But if you just want to chill in a beautiful setting, it’s a perfect pick-me-up.

Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind tries to present the entire Homo Sapiens existence in a single book, through the analysis of three fundamental revolutions that witnessed humankind as the protagonist: the Cognitive revolution, the Agricultural revolution and the Scientific revolution.

Keeping this simple chronological structure, the author provides challenging ideas and presents historical fact in a way that I haven’t personally seen before.

I found the book well written and thought provoking. Most of the time the author doesn’t provide a single view on a topic but presents different angles and interpretations explaining their pros and cons. This often led me to argue by myself for one or the other view and comparing my observations to the ones provided by the author.

Throughout the book you can hear loud and clear what is probably one of the obsessions of the author. Most of the topics presented are filtered through the question “Did this improve the happiness of humankind? What about the happiness of the individual?”. This, as far as I know, is a reading that is seldom presented in schools or by other historians and gives a whole different perspective on history. You will find yourself challenged by claims that might have never occurred to you and might make you uncomfortable. You will be asked to rethink or solidify your positions on sex and gender, twentieth century ideologies, religion, racism, slavery, equality, animal rights, morals and ethics, individualism, nationalism and consumerism.

The author saves the last couple of chapters for what they probably consider the most important questions to ask ourselves. Are you happy? Are you entitled to decide of your own happiness? What is happiness? Is it equivalent to pleasure? Can we reverse engineer happiness? And again, can we hack evolution and take control of it, decide where to go next? Can we achieve supernatural abilities, enhance ourselves or are we doomed to go the way of Dr. Frankenstein? What are the ethical implications of all this? Can we even imagine a future in which Homo Sapiens is not a “God on earth”, in which it’s not the dominant species?

At times the author makes little effort to hide their personal beliefs. From reading the book I would assume the author is vegan (or at least supports the animal rights movement) and a Buddhist (especially interested in the peculiar Buddhist idea of happiness). This is not necessarily a negative but occasionally alters the impartiality of the author in analyzing a topic.

The last chapter also provides a series of “predictions” about the future of humans and technology. While this is done to lead the reader to more philosophical questions, these are still predictions of a 2014 (non necessarily tech-savvy) person. This felt like reading a novel from the Fifties talking about the technology of the future. A few of them have a sci-fi taste and in other cases are simply outdated (especially when it comes to AI and superintelligence). This is not necessarily the author’s fault and actually confirms the fact that scientific research is advancing faster than the average Homo Sapiens can manage to process.

I would suggest it to anyone who is looking for a non-fiction book than can help you rethink yourself as a person and ourselves as a species.

In Some Assembly Required, biologist Neil Shubin explores a theme he already touched upon in his 2008 book Your Inner Fish and the 2014 PBS documentary of the same name: How do complex bodies, with all their specialized functions, evolve? How does evolution build on that which has come before?

To answer these questions, Shubin revisits the discoveries of biologists and naturalists of the past and introduces some of the most recent findings of molecular biology. This is a popular science book, so scientific facts become stories whose protagonists are brought to life with biographical detail.

The key concepts Shubin introduces include:

-

how biological traits that have evolved for one function are re-purposed (exapted) for another (e.g., feathers likely evolved first for temperature regulation, then were exapted for flight);

-

how small changes in embryonic development can have dramatic effects on the resulting individual—e.g., the slowing of physiological development known as neoteny, where adults may retain traits otherwise only seen in the young;

-

how gene duplication events (e.g., via self-copying genes known as transposons or “jumping genes”) enable evolution to experiment with myriad small variations of existing genetic recipes, which has led to vast gene and protein families;

-

how plant and animal cells incorporated previously free-living organisms and thereby gained crucial new capabilities, the classic examples being mitochondria (the powerhouses of animal cells) and chloroplasts (the photosynthesis engines of plant cells);

-

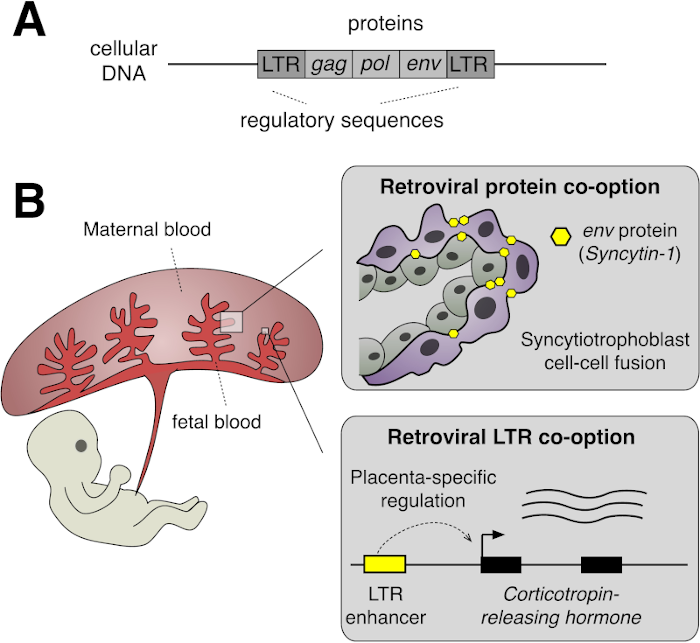

how viral elements have made their way into our DNA and have been co-opted for important biological functions (e.g., to make the protein syncytin, which is a key component of the placental barrier between fetus and mother).

Shubin explains how evolution often arrives at the same solution multiple times, with different genetic origins, and illuminates why some evolutionary pathways are likelier than others.

A retrovirus upon integration in the host genome (A), where its genetic code has been co-opted for building a protein used in placental development (B, top), and for the regulation of birth timing (B, bottom). (Credit: PLOS Biology / Edward B. Chuong. License: CC-BY.)

The book only scratches the surface of these concepts, and much of what it does cover is likely to be well-trodden ground for readers who have picked up a book about evolutionary biology since their school days. At the end of each chapter, I found myself hungry for more detail.

To Shubin’s credit, in the final section of the book, he provides a kind of afterword for each chapter, which includes sources and additional reading recommendations. I found this approach much more useful than a conventional bibliography or a set of disjointed footnotes.

I would give this book 4 stars — it’s a light, quick and engaging read on a fascinating topic. For readers looking for more breadth or more depth, I would recommend the following writers:

-

Richard Dawkins, if you are not put off by his politics, is still one of the best science writers I know. The Greatest Show on Earth: The Evidence for Evolution (2009; reviews) is a passionate, detailed and eloquent introduction to evolutionary biology.

-

Nessa Carey has a remarkable talent for getting as close to the science as possible while still writing for a lay audience. I read The Epigenetics Revolution (2012) and was deeply impressed by her clarity and ability to break down very complex concepts.

-

Andreas Wagner is a biologist bringing his own ideas to a larger audience through popular science writing. If the science behind it withstands scrutiny, Arrival of the Fittest (2014; reviews) could well be turned into a new chapter in the next edition of Some Assembly Required.

In short, Wagner argues that in order to find new functions for old genes, evolution has to take a “genetic walk” from A (old function) to B (new function). He explains the importance of neutral mutations in these genetic walks. His latest book, Life Finds a Way: What Evolution Teaches Us About Creativity, looks similarly fascinating.

If you’re on the fence about Some Assembly Required, consider getting a copy of the PBS documentary Your Inner Fish. It showcases Shubin’s storytelling talent while still packing a good amount of science. If you enjoy it, you’re unlikely to be disappointed by Some Assembly Required.