Latest reviews

Der Laden

Im Bull’s Kitchen ist vieles wie in den anderen Burgerläden dieser Zeit. Es wird am Tresen bestellt, man bekommt ein Ufo zur Benachrichtigung und die Einrichtung ist modern und ein bisschen auf Fabrikhalle getrimmt. Oder zumindest so wie sich viele das Industriehallendesign vorstellen. Mir hat es gefallen. Kostenloses WLAN inklusive. Aber man ist ja nicht zum Surfen hier. ;)

Logo des Bull’s Kitchen in Hannover

Die Burger

Die Speisekarte ist übersichtlich klein - ein Umstand den ich sehr begrüße und daher nicht in die Verlegenheit komme etwas auszusuchen was wohl nur angeboten wird weil es ein Must-Have ist. Die Wahl fiel auf den Cheese Burner und den Tam Çoban. Beim ersten Burger spricht der Name für sich. Ein sehr gut gewürzter Cheeseburger. Beim Zweiten müsste man schon erweiterte Fremdsprachenkenntnisse haben. Aber ein Blick auf die Karte hilft: Lamm, Weichkäse und karamellisierte Zwiebeln in einem Vollkornbrötchen. Dazu kamen Süßkartoffelpommes und die obligatorische Fritz-Kola im Menü. Das Fleisch kann man Medium oder durchgebraten bestellen. So bekommt jeder das Fleisch so, wie er es mag. Und das Fleisch ist im Bull’s Kitchen sehr gut. Ebenso wie der Rest zwischen den Brötchenhälften. Diese werden innen kurz angeröstet und mit Öl beträufelt damit es nicht so labberig durch die Soße wird. Und auch die anderen Zutaten sind erstklassig.

Tam Çoban Burger im Bull’s Kitchen in Hannover

Fazit: 4 von 5 Sternen

Aber warum keine 5 Sterne? Die sehr reservierte Bedienung an der Kasse inklusive Empfang und Ansprache kann man verbessern denn dann klappt es auch mit der Bestnote.

In contrast with time travel adventures, the genre of alternate history tells stories set in timelines that have already been altered. So, someone or something prevented Adolf Hitler from being born—now what? The most well-written alternative histories can deepen our understanding of real history, by re-examining the causes and effects that made our world what it is.

The Way It Wasn’t is a 1996 anthology edited by Martin Greenberg that assembles thirteen short stories of varying quality. There are only three that stood out to me as good or excellent:

-

Robert Silverberg’s “Lion Time in Timbuctoo”, an adventure set in a world where the Black Death was far deadlier than in ours, and different empires are struggling for power. Silverberg previously invented this alternative timeline in a novel called The Gate of Worlds, and Lion Time itself is short on worldbuilding and history, but it’s still a fun tale once it gets going.

-

Pamela Sargent’s “The Sleeping Serpent”, which describes an encounter between Mongols and Iroquois, in a timeline in which the Mongols are controlling continental Europe. Sargent has written a 700-page tome novel about Genghis Khan (Ruler of the Sky), and the quality of this story reflects her scholarship.

-

Kim Stanley Robinson’s “Lucky Strike”, which is about the morality of the use of nuclear weapons—and whether the decisions of individuals can make a difference.

Three stories are about US presidents—”Ike at the Mike”, which imagines a music career for Dwight Eisenhower; “Over There”, in which Theodore Roosevelt gets his wish for a final World War I adventure with the “Rough Riders”; “The Winterberry”, in which JFK is not dead, but no longer the man he was. These stories are more about presidents as celebrities and myths than about their real lives or the consequences of their actions, and I found them wholly unnecessary (“Ike at the Mike” was execrable).

If you find this book in the bargain bin, you’re likely to enjoy some of the stories, but given the hit-or-miss quality of the selection, I would suggest seeking out the highlights above instead of buying the anthology.

A 576-page novel about a fictional British rock band trying to make its way to international stardom in the late 1960s? That really doesn’t sound like my cup of tea—but this one was written by one of my favorite authors, David Mitchell (Cloud Atlas, The Bone Clocks), so it was an instant purchase for me.

Utopia Avenue tells the story of the eponymous band from the perspective of its members—Dean Moss, Elf Holloway, Jasper de Zoet, Peter “Griff” Griffin—and their manager, Levon Frankland. Each chapter is named for one of the band’s songs and focuses on one of the main characters. (To promote the book, Penguin created a PDF with complete lyrics written by Mitchell for several of the songs, attributed to Utopia Avenue’s songwriters. Actually singing them might prove challenging!)

The book does not overplay the rags-to-riches angle of a band struggling towards success. Instead, it focuses especially on Dean, Elf, and Jasper, whose different class backgrounds and personal struggles (with sexual identity, with mental health, with discrimination, with estranged family, with grief) elevate the book beyond its colorful setting.

Astute Mitchell readers will recognize Jasper’s last name from The Thousand Autumns of Jacob de Zoet, which is about the adventures of Jasper’s great-great-great grandfather. Jasper’s story intersects with the supernatural elements of the Mitchellverse, but this is only one thread among many, and Utopia Avenue stands entirely on its own.

Nonetheless, it’s par for the course for Mitchell to include plenty of references to prior works, and he does so with gusto, including a significant role for Luisa Rey, the Spyglass writer from Cloud Atlas (unforgettably portrayed by Halle Berry in the 2012 movie).

Cartoon celebrities

What’s more unusual is that Utopia Avenue is chock-full of real-world cameos, from David Bowie to John Lennon, from Jimi Hendrix to Leonard Cohen. Mitchell tries to make these encounters brief and memorable, but some readers will find the portrayal of these (in some cases recently) deceased celebrities jarring and cartoonish.

Mitchell might agree. He loves playing with the contrast between the serious and the farcical, the exaggerated and the real. Compare Cloud Atlas: Is Luisa Rey the character of a mystery novel inside the novel, or a fictionalized Karen Silkwood? The world of Utopia Avenue is the same one in which writer Dermot Hoggins throws book critic Felix Finch off a twelfth floor balcony.

I enjoyed the celebrity cameos without taking them too seriously. I love that some readers have compiled playlists on Spotify and on YouTube of the many works referenced in Utopia Avenue. Clearly, these readers felt transported by the book—not to the historical 1960s, but to an imagined place and time. In Mitchell’s own words, he evokes lacunae, just like when Dean Moss discovers a hidden church while wandering Rome:

In memory and in dream, he’d revisit this lacuna in time and in space. The place was a part of him now. Every lifetime, every spin of the wheel, holds a few such lacunae. A jetty by an estuary, a single bed under a skylight, a bandstand in a twilit park, a hidden church in a hidden square. The candles at the altar did not burn out. (p. 330)

Utopia Avenue is bright and stylish; it plays with plenty of tropes and stereotypes (sometimes to its detriment), but does not neglect the inner lives of its characters. If you’re new to Mitchell and the subject-matter does not appeal to you, you may want to sample his other works first—The Bone Clocks is fantastical and accessible; Cloud Atlas is masterful and deeply moving; Ghostwritten and number9dream are showy and experimental; Slade House is short and creepy; Thousand Autumns is an adventure in a different time; Black Swan Green is evocative and wondrous, a personal favorite.

The Taiping Rebellion raged in China from 1850 to 1864. It was a civil war (overlapping with America’s) in which 20-30 million human beings or more lost their lives. The Taiping sought to overthrow the Qing dynasty and establish a Christian theocracy in its place. Their leader, Hong Xiuquan, proclaimed that he was Jesus Christ’s brother (presumably not that one). Where the Taiping ruled, the temples and “false idols” of Buddhism, Confucianism, Taoism, and other ancient beliefs were often smashed to pieces.

In Autumn in the Heavenly Kingdom (2012), historian Stephen Platt retells the story of the rebellion and Western involvement in the conflict. After setting the stage with several maps, a timeline, and dramatis personae, Platt centers the experiences of memorable and colorful characters like Hong Rengan (the Taiping Prime Minister who envisioned Western-style reforms in China), Zeng Guofan (an imperial scholar-general who employed exceptional brutality to suppress the rebellion), and Frederick Townsend Ward (an American soldier of fortune who helped fight the Taiping).

A dynasty on its knees

After the First Opium War (1839-1842), the ruling Qing dynasty was near collapse. The overtaxed peasantry and gentry flocked to the Taiping in droves. Due to their Christianity-inspired and pro-Western ideology, they also had Western supporters, especially in the missionary community which hoped to help “correct” the group’s more idiosyncratic teachings. But along the way, Britain picked the side of the Qing dynasty, helping bring about the end of the rebellion.

When a Taiping force reached Shanghai (one of the treaty ports opened to foreign trade by force) in 1860, Taiping commander Li Xiucheng sent an advance letter assuring the foreigners in the city that the Taiping wanted positive trade relations, and that no foreigner would come to harm. Britain’s trade representative Frederick Bruce refused to even open the letter. Instead, British and French forces helped repel the Taiping forces from Shanghai—while simultaneously waging a Second Opium War against the Qing dynasty which culminated in the destruction of the Imperial Summer Palace in Beijing.

Reconstruction of the Imperial Summer Palace in Beijing, which was looted and destroyed by Anglo-French forces in the Second Opium War. (Credit: Guo Daiheng / Beijing Re-Yuanmingyuan Company Limited. Fair use.)

Gunboats and mercenaries

Britain continued to strenuously assert its neutrality in China’s civil war, but the intervention in Shanghai marked the beginning of increasingly active efforts to help suppress the Taiping: by imposing conditions on their military movements, by selling arms to the Qing empire (including an aborted attempt to sell China’s rulers a small fleet of gunboats known as the “Vampire Fleet”) , and through support for Frederick Ward’s mercenary force, the “Ever Victorious Army”, which would come to be led by a Brit, Major Charles “Chinese” Gordon.

The Qing dynasty lasted until 1912. Would the empire have defeated the Taiping without Western help? If not, would Hong Rengan’s vision of a peaceful, modern China have prevailed—or would Hong Xiuquan have led an increasingly fanatical theocracy, worse in its oppression than the rulers it sought to displace?

While Platt’s narrative is sympathetic to the Taiping (as is modern China, which has sometimes portrayed them as proto-Communists), he does not attempt to answer those questions. Instead, Autumn in the Heavenly Kingdom, together with its “prequel” about the First Opium War, Imperial Twilight (reviews), helps us understand the wounds of colonialism and the human cost of empire in all its forms. It may also provide clues to modern China’s obsession with totalitarian political control.

The verdict

As in Imperial Twilight, Platt succeeds marvelously in making this history engaging, at the expense of attempting to chart out the larger patterns of the conflict (e.g., the economic impact of the First Opium War on the Qing dynasty, the ideological development of the Taiping, the volume of arms sales). Like Imperial Twilight, I recommend Autumn in the Heavenly Kingdom unreservedly as a starting point to explore the history of China in the 19th century.

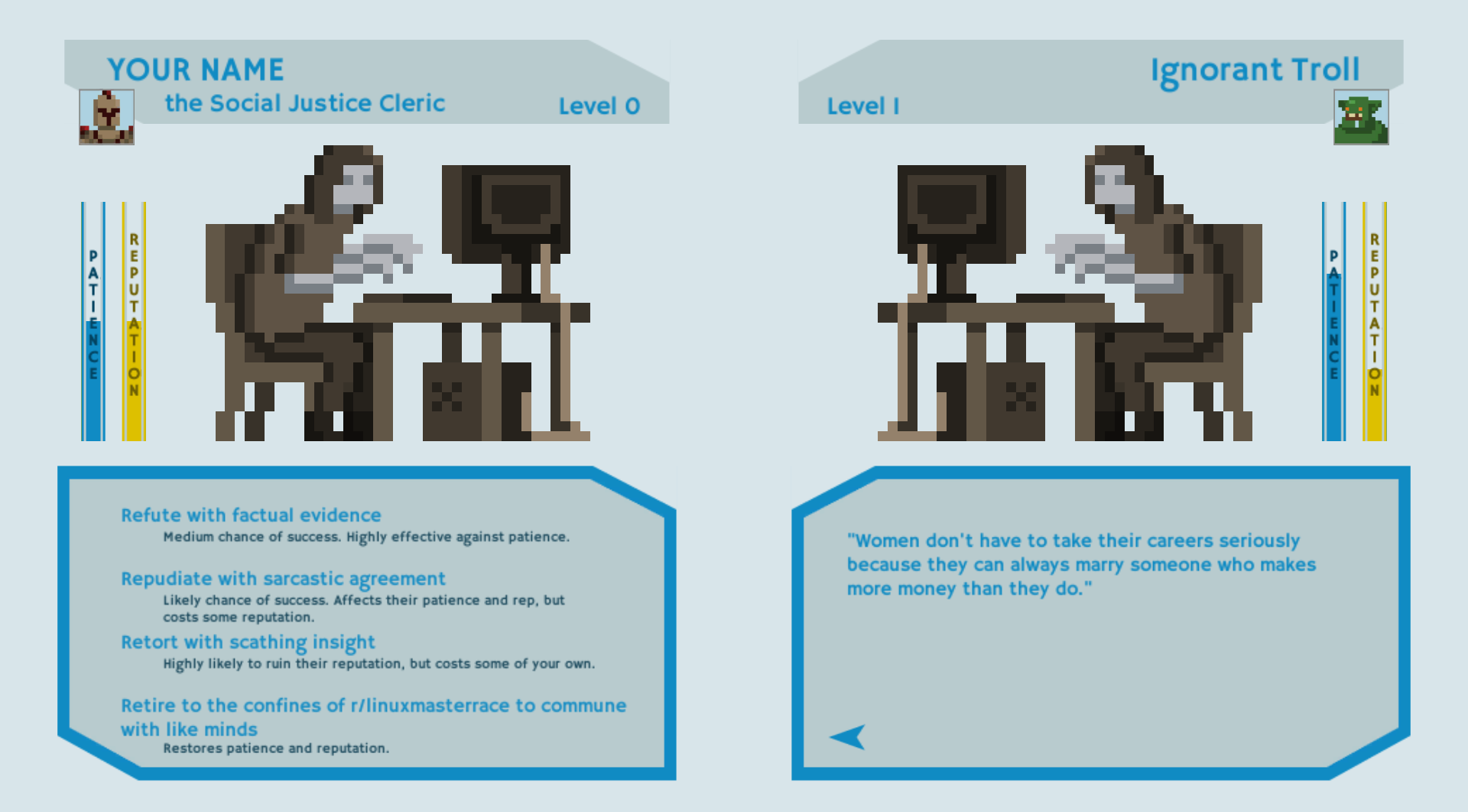

The game makes you a literal Social Justice Warrior fighting trolls on the internet. The art style and music come together nicely to to feel like an 8 bit adventure game.

Social Justice Warriors gameplay (Own work. License: CC-BY-SA.)

Gameplay

The game is fairly simple, you choose 1 of 4 characters with unique attacks to fight trolls. Every time you attack, you’ll see lines from the trolls like “Women don’t have to take their careers seriously because they can always marry someone who makes more money than they do”. You fight trolls until someones reputation or patience reaches 0. The game feels fresh for the first 15 minutes until you’ve seen all the troll lines, stooped to using attacks that hurt your reputation and tried all the characters.

Verdict

Game has a cute theme, but gameplay quickly becomes boring. There’s also nothing notable about the message, fighting trolls on the internet is futile wasn’t even insightful in 2014 when the game was released. This game may have worked well as a short video instead.

Oberberg. Karin Nagelschmidt hat ihren ersten Roman vorgelegt: „Die Erbschaft”, erschienen im Bergischen Verlag. Es ist kein Lokal-Krimi, sondern eine spannende Beziehungsgeschichte. Motor der rätselhaften Handlung ist der kürzlich verstorbene Frank. In seinem Testament hinterlässt er seinen ehemaligen Studienfreunden Orazio, Gregor und Valentin ein Vermögen und eine Villa in Nizza. Einzige Bedingung: Sie müssen das Vermögen in ein humanitäres Projekt in Köln investieren, das sie als Team zu gründen haben, in knapper Frist. Erst dann gehört ihnen die Villa. Dummerweise hat sich das Trio seit 14 Jahren aus den Augen verloren. Ist die Aussicht auf die Villa Grund genug, sich zusammenzuraufen? Schon bald stellt sich heraus, dass die Männer weit davon entfernt sind, ein Team zu sein. Und der Notar Dr. Veith heizt mit Briefen des Verstorbenen die schwelenden Konflikte immer wieder an.

Erzählt wird aus der Sicht des Orazio, Kunsthistoriker mit einem Hang zu hübschen Frauen. Seine Ehe mit der kränkelnden Miriam ist freudlos, trotz der beiden Mädchen, die Orazio über alles liebt. Gregor ist der skeptische Macher, der hinter dem Nachlass üble Tricks vermutet. Valentin ist ein poetischer Träumer. Und Ada ist seine Freundin, die mit hocherotischer Ausstrahlung die Gruppe zu sprengen droht.

Nagelschmidt gelingt eine klare Figurenzeichnung der Protagonisten. Die Frauen bleiben geheimnisvoll bis zum Showdown, der alle mit Schuld und Verstrickung konfrontiert. Geschickt meidet die Autorin hier die Gefahr, ins Allversöhnende abzugleiten. Lokalkolorit ist bei ihr nie heimattümelnder Selbstzweck, sondern dient der Figurendarstellung. So entsteht eine spannende Geschichte über Liebe, Verrat und Verantwortung, Am überraschenden Ende staunt Orazio, „wie viel Einfluss das Ungesagte doch hat”. Und der Leser empfindet mit den Helden schließlich eine Art Einverständnis mit dem Leben.

Die Autorin (* 1957 in Köln) ist frisch pensionierte Lehrerin des Kaufmännischen Berufskollegs und lebt seit 30 Jahren in Gummersbach. Ihr Talent hat sie u.a. in der Gummersbacher Schreibwerkstatt entwickelt. Ihr großes Thema sind die Menschen und ihre Milieus, die sie gern und genau beobachtet. „Über mich selbst möchte ich gar nicht schreiben. Da fehlt mir die nötige Distanz.”, sagt sie im Gespräch. Das war auch der Grund, weshalb sie die männliche Perspektive für ihren Roman gewählt hat. „Mich interessiert, was der einzelne unter einem guten Leben versteht.” Und sie fragt nach den Irrtümern, an denen wir oft krampfhaft festhalten – zumindest im Roman kann sie die Menschen davon befreien. Ihr nächstes Buchprojekt wird von Flucht und Verfolgung erzählen: „Jetzt habe ich die Zeit dafür.”

Karin Nagelschmidt: Die Erbschaft – Bergischer Verlag, 317 Seiten, ISBN 978-3-945763-76-6, 13,95 €

19-year-old Gail and Zella Kastner, identical twins born to a Montreal family, were honors students in high school, “popular with the boys and in love with skating and horse-racing” [source]. But one day in 1953, Gail made the fateful decision to seek help for mild depression anxiety at the highly reputable Allan Memorial Institute.

What followed was a journey through hell: electroshock treatments, drugs, and attempts to “de-pattern” her brain—reprogramming her personality in an attempt to cure her.

She emerged in a childlike state: sucking her thumb, talking like a baby, demanding to be fed from a bottle, and urinating on the floor. She also suffered memory loss and couldn’t recognize members of her own family, not even her twin sister, Zella [source]

Gail’s life derailed, and it’s only after long legal battles that she was awarded modest damages in 2004. Many more patients would be subjected to these destructive techniques by the institute’s founding director, Ewen Cameron, a towering figure in international psychiatry at the time. His work on de-patterning and “psychic driving” would become known as the Montreal experiments.

Gail’s story is referenced in a single sentence in Stephen Kinzer’s new book, Poisoner in Chief, a biography of Sidney Gottlieb, the head of the CIA’s notorious MK-Ultra program. As part of the program, the CIA became aware of Cameron’s work, and decided to invest in his research by way of a front group ominously called the “Society for the Investigation of Human Ecology”.

But more than MK-Ultra’s notorious experiments with LSD, which Kinzer describes in detail, the Montreal experiments help us to draw the line between what happened in the 1950s and the “enhanced interrogation techniques” applied at CIA black sites around the world. Sensory deprivation, noise, endlessly repeating recorded messages: these methods have stood the test of time in the psychological torturer’s arsenal.

That’s also the perspective of a new documentary, Eminent Monsters, by Stephen Bennett, which focuses heavily on Cameron’s experiments, on the treatment of the “Hooded Men” in Northern Ireland in 1971, and on torture in the “War on Terror”. (You can watch it in full on Prime Video.)

While Ewen Cameron directed its work, many patients were admitted to the Allan Memorial Institute with mild symptoms and left with lifelong psychological damage. (Credit: The Cosmonaut. License: CC-BY-SA.)

In contrast, Kinzer’s book tells the whole story of Gottlieb’s work, or at least the parts which we have a record of. Gottlieb was involved in many of the CIA’s dirtiest plots—from an assassination plan targeting Patrice Lumumba (who was later killed in a Belgian-backed plot) to CIA-run brothels in the United States where patrons of sex workers were drugged and observed. Other highlights of Gottlieb’s career include:

-

Overseeing work at black sites like the notorious Camp King, where the US collaborated with nazi war criminals like Kurt Blome to conduct experiments on enemy prisoners, often ending in death;

-

Organizing a massive campaign to test LSD on thousands of students by funneling grant money to researchers—a campaign so vast that it unintentionally sparked the prominent role of LSD in student counterculture (John Lennon famously said: “We must always remember to thank the CIA and the Army for LSD”);

-

Drugging Frank Olson, a key figure in these programs, with LSD at a staff retreat. A few days later, Olson plunged to his death from a hotel window.

Kinzer paints Gottlieb as a troubled figure, a man with humanist sensibilities, who may have been riddled with guilt later in his life. Not a sadist, but someone who was radicalized by America’s anti-communist fanaticism to do whatever it takes in order to counter exaggerated or imagined threats.

There’s some gallows humor in these tales of a CIA so obsessed with LSD that people had to worry about spiked punch at Christmas parties, of experiments so bizarre that only the later Stargate Project (which sought to mobilize psychic “remote viewing” powers for intelligence) could top them.

Kinzer’s book is well-researched and includes some new and little-known material. As a biography, it is ultimately focused on the man Gottlieb, an approach which sometimes gets in the way of illuminating the context and consequences of his work. Bennett’s Eminent Monsters focuses more narrowly on the topic of psychological torture. While it is unlikely to dissuade those who believe that such methods are necessary to fight terror, it does a great job explaining their history and centering the victims.

Poisoner in Chief and Eminent Monsters are important contributions to understanding the intellectual foundations for modern torture programs. They also remind us of the importance of effective oversight of any intelligence agency, and what happens when “patriotic” fervor meets immense power without accountability.

The Princess Bride was only a moderate success at the box office, but since its release in 1987, it has become a cult classic. Its lovable characters left an indelible impression on many, and the film has bestowed us several pop culture quotes and assorted GIFs, e.g.:

-

“Inconceivable!” — “You keep using that word. I do not think it means what you think it means.“

-

“Hello, my name is Inigo Montoya. You killed my father. Prepare to die.“

-

“You seem a decent fellow… I hate to kill you. “ — “You seem a decent fellow… I hate to die. “

This one’s a classic, too:

The movie is based on a book, and if William Goldman is to believed, that book was written by a Florinese author named S. Morgenstern a long time ago, re-released in translated and abridged form by Goldman in 1973. Of course, he is most definitely not to be believed—but the fake origin story adds a charming narrative layer to Goldman’s novel.

At its heart, The Princess Bride is a comedic story of true love between Buttercup, a farmer’s daughter, and Westley, a farmhand. Their love is imperiled by the machinations of one Prince Humperdinck and his sadistic right-hand man, Count Rugen. Along the way, Buttercup and Westley cross paths with Inigo Montoya (a Spanish master swordsman), Fezzik (a Turkish giant), and Vizzini (a Sicilian criminal genius)

Compared with the movie, the book gives Inigo a proper backstory, helping lend emotional weight to the final confrontation between Inigo and the six-fingered man who killed his father. We also learn more about Fezzik the giant, although it’s a fairly worn out tale (the sweet, gentle giant who reluctantly learns how to use his strength).

But what of Buttercup? While she gets to boss Westley around for a bit in the beginning, she is quickly reduced to the traditional traits of princesses: beauty and devotion. One can argue that the book takes its stereotypes to such ridiculousness that they lose normative power, but that argument only goes so far.

Still, what saves The Princess Bride from becoming conventional and boring is its sense of humor. From the Rodents of Unusual Size (R.O.U.S.) to the Zoo of Death, from Miracle Max and his questionable cures to Goldman’s tall tales about S. Morgenstern, the book is an entertaining page-turner.

Modern editions include the first chapter of Buttercup’s Baby, a sequel to The Princess Bride that was unfortunately never completed (Goldman died in 2018). It gives us a small glimpse of further adventures that could have been.

Not everyone will adore The Princess Bride as much as its many devoted fans do, but if you are a lover of adventure and comedy, it may well earn a special place on your bookshelf and in your heart, or the heart of a smaller human you read it to.

After a long, bloody history of colonial rule, Britain finally abandoned in the Indian subcontinent in 1947. Against significant opposition, the Brits negotiated the partition of India into India and Pakistan. This led to a refugee crisis, mass violence, and the deaths of between 200,000 and 2 million human beings. The resulting so-called “Muslim homeland” of Pakistan was not the nation we know today, but a country divided into West Pakistan and East Pakistan, with a whole lot of India between them:

Partition resulted in a bizarre post-colonial map, with a divided “Muslim homeland” (home to millions of non-Muslims) bordering India. Credit: BBC. Fair use.

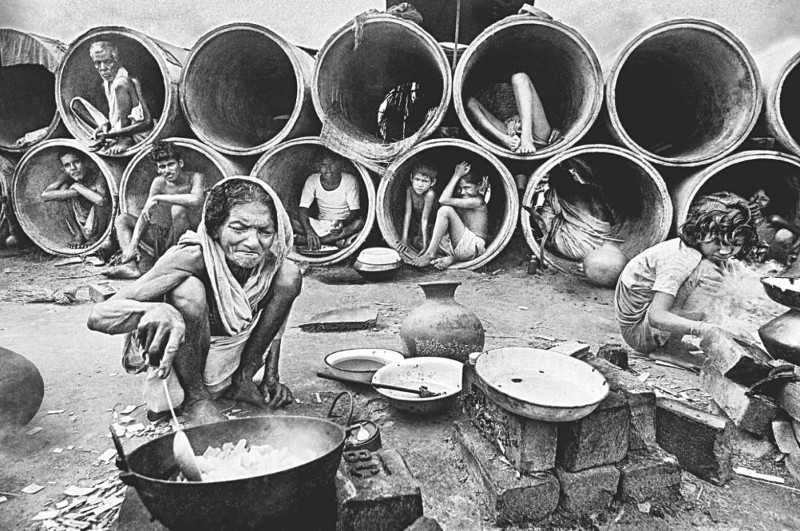

Less than 30 years later, the fiction of East Pakistan collapsed in genocide and war. After an election that would have shifted the balance of power to the Awami League, which sought independence for the East, Pakistan responded by abandoning its brief experiment with democracy and sent in its troops from the West. They unleashed atrocities that killed between 300,000 and 3 million people (often with weapons Pakistan had bought from the US). Hindus were singled out for extermination and expulsion, making this a genocide by every definition.

This spurred a refugee crisis that overwhelmed neighboring India, giving it cause and pretext to arm its Bengali neighbors and, ultimately, help them fight the Bangladesh Liberation War. The country of Bangladesh was born from the blood and the ashes. Brutal revenge killings against anyone who was seen as a collaborator with the Pakistani military followed.

The Blood Telegram by Gary J. Bass tells this story with special focus on the actions of US foreign policy decision-makers, chiefly Richard Nixon and Henry Kissinger. Nixon had developed a personal friendship with Pakistan’s dictator, Yahya Khan, and sought to preserve a strategic alliance with Pakistan, in part in order to use Yahya as a secret diplomatic channel in the planned opening of relations with the People’s Republic of China.

Bass uses the Nixon White House tapes, interviews, and countless historical documents to reconstruct a detailed picture of how the US government and its foreign policy apparatus responded to the genocide as it unfolded in East Pakistan.

A very clear picture emerges: Nixon and Kissinger did not care about the genocide, declined to put any pressure on Yahya to stop it, and bullied internal dissenters into silence. They refused to stop all pending arms transfers, and when the Bangladesh Liberation War started, they illegally used third countries (Iran, still ruled by the US-backed Shah, and Jordan) to funnel weapons to Pakistan. They tried to draw China more deeply into the conflict, and threatened India with an aircraft carrier.

“Salt Lake” refugee camp in Calcutta. Millions of refugees from the genocide overwhelmed India, a country already struggling with extreme poverty. (Credit: Raghu Rai. Fair use.)

“Our government has failed”

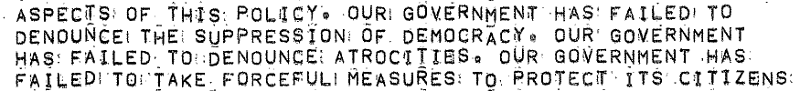

The “Blood Telegram” of the title was sent by Archer Blood, then US Consul General in Dacca soon after the genocide started. The diplomatic staff were witnessing the mass killings firsthand, and after repeatedly warning their superiors about the unfolding crisis, they prepared a confidential dissent statement to express their deep concern with US foreign policy.

Excerpt from the “Blood Telegram” itself, April 6, 1971.

Blood did not sign the statement, but he expressed his agreement with its contents. For his dissent, Nixon and Kissinger recalled him to the State Department’s personnel office back in DC.

Even in isolation, any defense of US foreign policy towards the 1971 genocide does not withstand scrutiny. There was no “pragmatism” here, because the US did not pragmatically push for political stability when it had the opportunity to, nor did it pragmatically choose one of the many alternatives for creating an opening with China.

Bass shows the role of emotion and prejudice in decision-making. Kissinger, who cultivates an image of a wise statesman and master of “realpolitik”, was ranting and raving about the Indians along with Nixon, and the two of them outdid each other with bizarre analogies (Yahya was “Lincoln”, the Indians were “Nazis”, Pakistan was being “raped” by India). The best that can be said about their actions is that they provided (inadequate) humanitarian aid to India in a “too little, too late” attempt to avert or delay war.

One fascinating aspect of this history is the role of the Soviet Union. An authoritarian regime, it allied itself with democratic India and supported the liberation of Bangladesh. In a complete reversal of Cold War stereotypes, here it was the Soviets who defended democracy and human rights, for their own reasons that were far more cool and pragmatic than Nixon’s emotional allegiance to a military dictatorship that pursued a course of self-destruction.

An incomplete portrait

The Blood Telegram is neither a full accounting of the events that led to the creation of Bangladesh, nor a comprehensive view of America’s foreign policy under Richard Nixon and Henry Kissinger. While Bass hints at other evils—the brutal escalation of the Vietnam War, the carpet-bombing of Cambodia, the installation of a murderous dictatorship in Chile—he focuses on his central thesis: different choices could have prevented or slowed the killing in East Pakistan.

Bass makes this case with commendable scholarly rigor, but an obsessive level of detail about the Nixon/Kissinger dynamic takes up space that could have been used to place these events in their larger context. In isolation, America’s complicity in the genocide in East Pakistan may seem like a historical abnormality. In the larger history of US foreign policy, which is littered with millions of avoidable deaths, it’s not the specific behavior of Nixon and Kissinger that was historically abnormal, but the vocal dissent represented by the Blood Telegram.

Homo sapiens spent 99% of its existence on Earth in a hunter-gatherer lifestyle. So it’s perhaps no surprise that the game Don’t Starve, where you gather twigs and berries and set traps for rabbits, has an incredibly addictive quality to it. Released by Canadian indie studio Klei Entertainment in 2013, Don’t Starve has since spawned a multiplayer variant and a fair amount of downloadable content (DLC).

The base game will keep you busy for a while. It combines roguelike elements (procedurally generated worlds) with crafting, farming, a day/night cycle, seasons, and many different ways to die.

For starters, there’s darkness itself: if you spend more than a few seconds in total darkness, you will die from mysterious causes. If you don’t eat, you starve (duh!). If you don’t find ways to preserve your food, it slowly spoils in your inventory. If you don’t sleep, you slowly go insane. Every few nights you get attacked by ever-growing packs of hounds. During winter, you may freeze to death. Or you could get killed by bees, frogs, spiders, giant birds, tentacles, pengulls, beefalo, did I mention tentacles, and myriad other creatures.

A small walled camp with a tamed baby beefalo, farms, and drying racks for meat. (Credit: Klei Entertainment. Fair use.)

Still, after a few early deaths (and maybe after reading a few spoilers online), the game becomes surprisingly chill. Most creatures don’t attack unless provoked or approached, and you can craft yourself a little fortress and prepare a good defense against the regular hound attacks. Just as you’ve gotten the hang of it, Don’t Starve lures you into Adventure Mode, where you get to face off against the game’s antagonist, a pinstripe-wearing half-demon named Maxwell, in extra-hard challenge worlds.

You also quickly unlock most of the game’s playable characters, all with different skills and weaknesses. So far I’ve mostly played as Wilson, but I look forward to playing as creepy-girl-with-the-dead-sister Wendy or as Woodie, a lumberjack with a talking axe.

As you may have guessed by now, the game does not go for realism: its art style is influenced by Tim Burton, and its world is littered with magical items and the means to craft them. You will also encounter sentient pig creatures living in little houses, who can be tamed to do your bidding, or brutally killed and turned into football helmets and meat.

Procedural generation works best if it creates worlds that feel like places worth visiting, not just empty rooms and corridors. Each game world in Don’t Starve is a place to be navigated: where are the rocks to mine, the berries to harvest, the trees to fell? As you survive days and nights, your brain starts to map out these game worlds just like it does any other place.

The Verdict

Don’t Starve is a masterclass in game design, with excellent controls and menus that make the complexity of its mechanics a joy to manage. While I didn’t find the artwork very appealing at first, it quickly grew on me, thanks to lighting and sound effects, cute animations and funny dialogs, and the living rhythm of the game’s plants and creatures.

The game has its dull moments where you just gather resources or wait for night to turn into day. But these quiet minutes also present opportunities to organize your inventory, to craft a needed item, or to plan out the next day.

Don’t Starve is available for virtually every platform now (including Linux, Android, and Nintendo Switch), and you can regularly find the Steam or GOG version on sale for $5 or less. Developer Klei Entertainment also deserves credit for publicly renouncing “crunch time” and pledging not to overwork its developers. I highly recommend the game, and I look forward to checking out Klei’s other titles, nearly all of which have received very favorable reviews.