Latest reviews

Cardinal Cross is a choice-driven visual novel about a space-traveling scavenger named Lana Brice, who unexpectedly finds herself caught up in a galactic conflict of an astrological nature. The game was written by Roman Alkan and published through her small indie studio LarkyLabs under its ImpQueen brand.

In this universe, predictions derived from the movement and position of celestial objects are as fictionally real as the Force in Stars Wars, or as the fungal excretions of sandworm larvae that make interstellar travel possible in Dune. In most other ways, Cardinal Cross employs familiar sci-fi tropes: cybernetic implants, space rebels, robots and AI, the works.

Lana Brice (left) is a space scavenger with strained family ties. (Credit: LarkyLabs. Fair use.)

Meet the factions

Lana Brice and her friend Wiz, the Mechanic, are part of group of planets known as the Raiders. These folks have gotten the short end of the stick in a conflict with another group known as the Morai System, and they’re generally treated like colonies.

In a black market transaction, Lana and Wiz come in contact with a rogue intelligence agent of the Morai, who is trying to purchase an artifact from them. Most people have cybernetic implants, but this guy is enhanced to the point of almost losing his humanity. He is dangerous, and so are his former employers.

Soon enough, Lana is caught up in a web of conspiracies and plots involving multiple factions. At its center is an astrological supercomputer which the Morai elite use to maintain power and control. Its predictions are not perfect: so-called “howlers”—some humans, objects, planets—elude it completely. (I’m guessing the term is a reference to errors and aberrations rather than monkeys.)

As you might expect from its astrological theme, much of the story revolves around whether our fates are our own to write if the stars seem to already foretell what they are. Thankfully, the story never gets bogged down in sophomoric arguments about free will—it plays out more viscerally through Lana’s choices. That is to say, your choices.

One way or another, Lana’s fate is in the stars. (Credit: LarkyLabs. Fair use.)

Choices and characters

Throughout the story, you get to make more than 100 decisions, typically about things to say, sometimes about things to do. A lot of them have a negligible effect, but you can romance three different characters, influence Lana’s personality, and achieve multiple endings.

The game signals the most important choices with a sound effect, and it makes it clear when you have the option to embark on a romantic adventure. It also displays the effect you have on others (“[name] is annoyed”, “[name] is amused”). These messages are sometimes off-point and immersion-breaking, but you can disable them entirely.

Cardinal Cross is not voice-acted, but it is exceptionally well-illustrated. Not only does it have beautiful character art, it has a ton of it.

There are 50+ side characters, and most of them are visually well-differentiated. It includes 70+ full-screen graphics during special events (“CGs” in visual novel lingo). In case you’re wondering: the graphics for the romantic outcomes are about as tame as what you’d find in a PG-rated movie.

The game has a soundtrack by Jeaniro, which creates suitable ambience without distracting from your reading experience. During the story’s most dramatic moments, the music becomes boisterous or tense, generally fitting the text well.

The story is substantive, but it doesn’t overstay its welcome. I reached an ending which suited my choices well in about 6 hours. After I checked out one other ending with the help of a guide, my total playtime added up to 8 hours.

A good yarn with a few flaws

Roman Alkan’s world-building helps to set the stage effectively, even if the introduction of the in-universe terminology is a bit tedious at first. I had three main issues with the writing:

-

It would have benefited from more editing (there’s some dialogue that’s a bit awkward; there are a few spelling/grammar issues throughout).

-

There are too many characters to keep track of, and the story shifts too quickly between them.

-

Relatedly, the story doesn’t give enough space to some key dramatic moments for us to really grapple with what just happened.

Know that it’s a violent game. Both Lana and the other characters may hurt—and kill—people they come across. Cardinal Cross does not explore its darker themes with the same sensitivity some visual novel writers (like Christine Love) bring to their work; here, transgressions don’t always have the reverberations you would expect.

All in all, though, it’s a good yarn. It riffs on the astrology theme in a way that I’ve personally not encountered in sci-fi (astrology is still annoying, don’t @ me!). It’s a great example of the art form, bringing graphics, music and writing together into a coherent whole. I would enjoy reading about the further adventures of Lana Brice, and will definitely pay attention to ImpQueen’s future works.

Liberapay allows to make recurrent donations to projects and people working on libre projects. It’s non-profit so the only cuts taken are the actual payment fees. You can support Liberapay itself by donating to it’s team within the service.

The site is easy to use and well made. There are good tools for managing your donations. It’s also easy to discover new interesting projects on the platform. I bet you will find there software you’re already using!

The Great Ace Attorney Adventures is the first game in a spin-off series from the modern classic Ace Attorney series of games built around criminal cases and court drama.

It differs mainly in that, as opposed to the rest of the series, it isn’t set in contemporary times, but during the late 19th century in Meiji period Japan and the British Empire.

You take on the role of Japanese Student Ryunosuke Naruhodo, who, after successfully battling himself out of the court for a crime he didn’t commit, goes abroad to the British Empire to study the British law and judicial system. Ryunosuke isn’t a law student, so this doubles as his journey of becoming a lawyer.

What the spin-off affords the game

The spin-off affords many exciting opportunities, but, of course, also challenges.

The game essentially being a clean slate allows for a sharp departure from the established series canon. The completely new cast of characters is the most obvious example.

Another such example is the soundtrack. Prior games in the series heavily relied on previously established melodies and themes. Those were usually either reused directly from previous games or arranged for jumping from one console generation to the next. The Great Ace Attorney features a completely original and orchestrated soundtrack. It sounds great, and it fits the period the game is depicting. But in my opinion, much more importantly, it helps the game establish an identity of its own.

The historical setting has also been used in a few compelling ways. So far, the series hadn’t made historical references at all. This was further complicated by the English localisation of the series changing the setting from Japan to the USA. Now, however, the game is brimming with historical references and factoids about late 19th century Japan and England. The game references laws from the time, local buildings in England such as the Old Bailey court, and famous historical figures like the Japanese author Sōseki Natsume.

New faces, old faces

While the game features a compelling original cast of characters, they largely fall into familiar archetypes.

The protagonist, Ryunosuke Naruhodo, comes very naturally after Phoenix Wright from the main series. He is determined and brave but also despairs easily in stressful situations in the courtroom. In Ryunosuke’s case, though, that character flaw is more understandable since he never studied to become a lawyer.

Susato Mikotoba is Ryunosuke’s judicial assistant. She clearly comes after Maya Fey from the main series, though not as playful. The charming, witty and empathetic character will be familiar to anyone who has played the original trilogy. On top of that, she is also quite assertive and forceful at times. I like her a lot, but I cannot help but see the missed opportunity for a female lead character here. The main series attempted to bring a female character to the cast of protagonists, but this was, for the most part, isolated to one case and neglected in the following release.

This game provided a clean slate, so the trouble of having to integrate a new character into a cast of well-known ones would have been avoided. And if you would have me believe that the British state would permit a foreigner with no formal education to work as a lawyer, why not a woman?

Our new pair of protagonists. (Credit: Capcom. Fair use.)

Two characters that defy previous archetypes in the series are Herlock Sholmes (yes, you read that correctly) and Iris Wilson. With a game set in Victorian London, the Sherlock Holmes character is a must, of course. Herlock is the same unstable genius we know from many stories in his young years. However, his deduction skills are not as good as the popular stories usually depict. He frequently gets small details wrong, and you’ll have a fun time correcting those mistakes. This twist is nice and, clearly, Sholmes is supposed to be one of the stars of the game, but I find the character of his assistant, Iris Wilson, much more interesting.

Iris Wilson is far more than just a gender swap for Dr Watson. She is a child prodigy, inventor, and chronicler of Sholmes’ adventures. At just ten years of age, Sholmes acts as her adoptive father of sorts, but she comes across as much more mature than him. She is charming and intelligent, and I’m sad we only see so little of her in this game.

As opposed to Herlock, who is a synthesis of the many different renditions the character has seen in fiction, Iris is almost completely original. Sholmes is what you would expect, but the only thing of Watson that remains in Wilson is that she is the chronicler of his adventures and that they live together.

The final character that sticks out is the series-typical prosecutor: Lord van Zieks. He is pale and dressed like an English aristocrat. This makes him look like a vampire and the game heavily leans into that. He absorbs the entire courtroom with his assertive personality every time it’s his turn to speak. His theme that prominently features a harpsichord and hits you like a brick wall of sound really sells those moments.

Van Zieks is very fun to watch. He often plays around with a wine glass of his: filling it, drinking from it, tossing it, or crushing it—I certainly appreciate the Castlevania references. He makes for a top contender for Top Prosecutor in the series, and that’s a title with tough competition.

Overall I’m happy with these new characters, but also a bit sad that largely the game falls back on established tropes instead of trying new things like with Sholmes and Wilson. This instance of a spin-off would have been the perfect moment to do it.

Old themes extended and revised

The Great Ace Attorney Adventures doesn’t waste this opportunity of a new beginning by just continuing the themes of the series and leaving it at that. Entirely new thematic strands are being explored here.

For one, the series, thus far, explored several issues in the legal system, often in the hyperbolic way. We are to understand that the justice system is not just at all. It is never explained, however, how it came to be that way. That is where this game comes in.

The Great Ace Attorney Adventures explores how the Japanese legal system was formed during the Meiji period of liberalisation and how it was greatly inspired by the legal system of the British Empire. When Ryunosuke goes abroad to London, we see many of the same issues already present. It’s very interesting to see this unfold, and it gives this game the fresh coating you would expect from a spin-off.

Certain aspects of the British Empire are greatly emphasised, even caricatured at times, to deliver an image of Britain that reflects Japanese views of it at the time. One such heavily emphasised thing is the technological superiority of the British Empire. The Japanese Empire, in its pursuit of liberalisation, sought to partially imitate the British Empire. As such, Japan is seen as technologically unadvanced, and one looks with marvel at the technological achievements of the British.

When our protagonists arrive in London, they speak at lengths about how different and greater everything is. The first interaction with the British legal system leads them to the office of the Lord Chief Justice, where a huge mechanical construct of gears looms in the background. While that is architecturally impractical and would make for a terrible place to do office work in, it drives home the message the game is trying to convey very efficiently.

The game does not solely portray British society as superior it also makes it clear that they see themselves that way. This leads to broaching the issue of the open white supremacy of Europe at the time. There are a lot of instances where racial prejudice is directed at the Japanese characters in this game. While certainly unpleasant, it obviously has its place in a game making historical commentary. But I can’t say that I care much about this aspect. It boils down to the Japanese characters taking the racist abuse and later proving the person making racist remarks wrong. This happens by showing their competency, or that they possess a positive character trait that contradicts the stereotype. I really dislike this because would the racism have been fine if the racist stereotype was confirmed in that instance? It makes for shallow commentary, that’s it.

Beyond that, another interesting component of the game is the jury. A group of six London citizens, chosen at random to decide the verdict. The game portrays these people as impulsive and easily swayed, effectively showing that involvement of the public like this doesn’t make for a better justice system.

This is interesting because in Apollo Justice: Ace Attorney, the “Jurist System” is presented as the solution to the game’s final conflict. This is not necessarily a contradiction, even though it might appear at first that the expressed opinions have changed here. The series often times shows your protagonists subverting, or outright breaking the law to peruse legal justice in this series. Clearly, that wouldn’t make for a great legal system. And yet these actions are shown as essential to deliver justice. The way this looks to me is that the game is saying that no justice system is capable of delivering justice in all cases. It might have previously looked like advocacy for a jury system, but this game clearly rejects that.

The game also continues the theme of belief in the justice system being like a religion. The Old Bailey courtroom looks very similar to the insides of a church with its stained glass windows. That house never had windows like that, but one would be missing the point if one were to criticise the game for not being historically accurate. In Gyakuten Kenji 2, the windows of the high prosecutorial office were styled similarly. Clearly, the game is connecting itself with this broader established theme. Though that connection is much thinner than in previous titles. Gyakuten Kenji 2 features the topic much more prominently, and Ace Attorney: Spirit of Justice, released one year after this one, made it the entire premise of the game, so I am not complaining.

There are other moments in the game that felt like they were commenting on previous titles in the series. Most noticeably, when the game makes you defend a guilty person, similarly to Justice for All. Except here, it isn’t the big revelation at the end of the game, but instead, it is used to build a story of betrayal and trust. The game gives you a case that violates your trust, and in a later case builds that trust back up again.

The big difference between the two clients used to tell the story is wealth. While your wealthy client uses you as a pawn to cheat the system, the other person is poor and has no one to put their faith into. The game’s message is clear: it is the poor people that need your help in this system, not the wealthy. I like this because it is much more in line with the identity the games developed over the years and ask much more interesting moral questions than: “But what if you defend a murderer?”

The gameplay additions

By now it should be clear, how this spin-off does take some new directions, but mostly tries to stay faithful to the core of the series. The gameplay is no different.

Largely the game follows the same gameplay tropes as the rest of the series and the additional court room mechanics from Professor Layton vs. Phoenix Wright: Ace Attorney. This means multiple people can and almost always will testify simultaneously. Along with that, there are “Pursuits”, which are essentially ways of furthering the cross-examination by pressing other witnesses on the bench for their thoughts on the current statement. I’m happy these are back and are allowed to shine in a proper Ace Attorney game and not just a crossover.

A new addition to courtroom sections comes with the jury. When the jury unanimously advocates for a guilty verdict, you get the chance to examine the jury’s grounds for doing so. These jury examinations function similarly to cross-examinations. Each juror presents their reasoning as a statemented. But unlike cross-examinations, your goal isn’t to uncover a lie, but to change the juror’s mind to prolong the trial. You do this by pitting contradictory statements by two jurors against each other.

The jury examinations introduce a new dynamic into the court room, because the way you would usually progress in such a section is by presenting evidence, but here it exclusively works with the statements themselves. This isn’t entirely new, though. In a previous game, there was an instance of having to press statements during a cross-examination multiple times in a specific order, to uncover the underlying contradiction. This didn’t work well however, because up until that point, you only ever had to press statements once.

Now, this idea was given its own feature and works much better that way. It makes for a welcome change of pace during court sections and you get to see more action from your main character, instead of a constant back-and-forth with the prosecution.

The other big feature that was added to exploration and examination sections are moments of so-called “Joint Reasoning”, where Ryunosuke joins intellectual forces with Sholmes. The detective may be world famous for his deduction skills, but in reality he often times gets crucial details wrong, even though his intuition leads him mostly on the right path. That’s where you as Ryunosuke come in. You get to identify and correct the small details Sholmes got wrong, to produce a properly useful deduction. This, again, is a bit like cross-examinations. You stop at a statement made by Sholmes and then try to figure out what he got wrong and present your own version of his statement. This usually involves looking around the environment for clues or presenting evidence from the court record.

All of this is presented in a very flashy and lively way. It almost feels alien to see characters move around so much on screen. Here the series is truly reaping the benefits transitioning to 3D.

It’s fun to watch, though the setup for it is bit longer than it needs to be in my opinion. But beyond that, it introduces some of the drama of the court room into the more calm exploration sections, which, just like the jury examinations, makes for a nice change of pace.

Sharply uphill, with rough decline

So far, I’ve been almost exclusively positive about this game. I really want to impress on you, how many good things this game has going for it. Other games in the series achieved great things with less. It is then a huge disappointment that a lot of this potential remains unused.

All of the great things I talked about so far get completely overshadows by the game’s poor pacing and structure. I will say, the game has a strong start, arguably the best in the entire series. Ryunosuke having to defend himself as a layperson in a case of high national interest immediately puts the stakes high. In the next case you get some breathing room with a pure investigation case. The game cleverly uses that time to introduce Sholmes and for you to learn about your soon to be judicial assistant, Susato.

It’s also a good setup for the next case which for balance, you’ll be spending entirely in court. Here the game also does a lot. It has to introduce the unique elements of the British justice system and introduce you to several new characters, including the new prosecutor van Zieks. At the same time, it’s the one chance Ryunosuke gets to prove his competency as an untrained lawyer. And further, the game makes you slowly realise that your client is a monster, who has deceived you into helping him in his scheme to cheat the justice system.

This makes for the climax of the game. It feels great up until that point, but after this there are two more cases. The one that follows is a lot slower, so you can recover from what came before. And the final case attempts to be the finale of the game, like is tradition for Ace Attorney. I say “attempt”, because it employs all the usual tropes to signal that the stakes are high, and even hints at the possibility of a conspiracy within the police. But all of this on reveal deflates to nothing. I cannot express just how disappointing that is.

I am not opposed to the third case being the high point of the game. It would be perfectly fine for this game and its sequel The Great Ace Attorney Resolve to play like one big game split into two, with the latter half of the first game properly preparing you for what will come in the second game.

To some extent, the game does do this. For example, it introduces you to Iris Wilson who no doubt, will have a huge role to play in the sequel, but then the game gets trapped in trying to deliver the typical Ace Attorney experience with a huge final case. But what is there just doesn’t live up to it.

In the end, there is a lot of hasty setup for a sequel, which leaves a sour taste in my mouth. It feels like the game saying that in the sequel, maybe, there is going to be an actually satisfying conclusion. All of this could have been avoided by not setting the expectations like that.

I am sure, that in that case, I would have finished this game much more satisfied.

Conclusion

The Great Ace Attorney Adventures has a lot of very interesting aspects to it. But unfortunately a lot of that potential is squandered by the game’s pacing and structure, which is terrible for a game that is part Adventure, part Visual Novel.

The first half of the game remains very good, even after finishing on a sour note. It makes you yearn for this game with the pacing issues absent.

Overall I can’t say this game is all that worth playing on its own. Especially not when there are so many other great games to choose from in this series. I hope that with all the build-up for the sequel, it turns out better than this game.

6/10

Von einem James Bond Film erwarte ich keine überzeugende Handlung oder sonstige cineastische Höhenflüge. Ich möchte gut unterhalten werden, viel Action auf der Leinwand sehen und die üblichen Beigaben, die James Bond Filme seit mehreren Jahrzehnten ausmachen.

Die Action ist gut gelungen, reichlich eingesetzt und passt gut in die jeweilige Lokation. Nicht fehlen darf ein umgebauter Aston Martin, der selbst den schlimmsten Angriffen der fiesesten Bösewichter widerstehen kann und dann mit einem eingebauten Arsenal an Waffen zurückschlägt.

Die Handlungsorte sind, wie fast immer, weltweit zu finden und meist von ausgesuchter Schönheit. Dies gilt auch für die sogenannten Bond-Girls. Wobei diesen schon seit einige Filmen mehr zugedacht ist als nur die Rolle des schmückenden Beiwerks.

Für eine kurzweilige Unterhaltung, wobei davon bei einer Laufzeit von 163 Minuten keine Rede sein kann, ist gesorgt. Der Film bietet perfektes Popcornkino und ist meiner Meinung nach eine würdige Verabschiedung von Daniel Craig als Superagent.

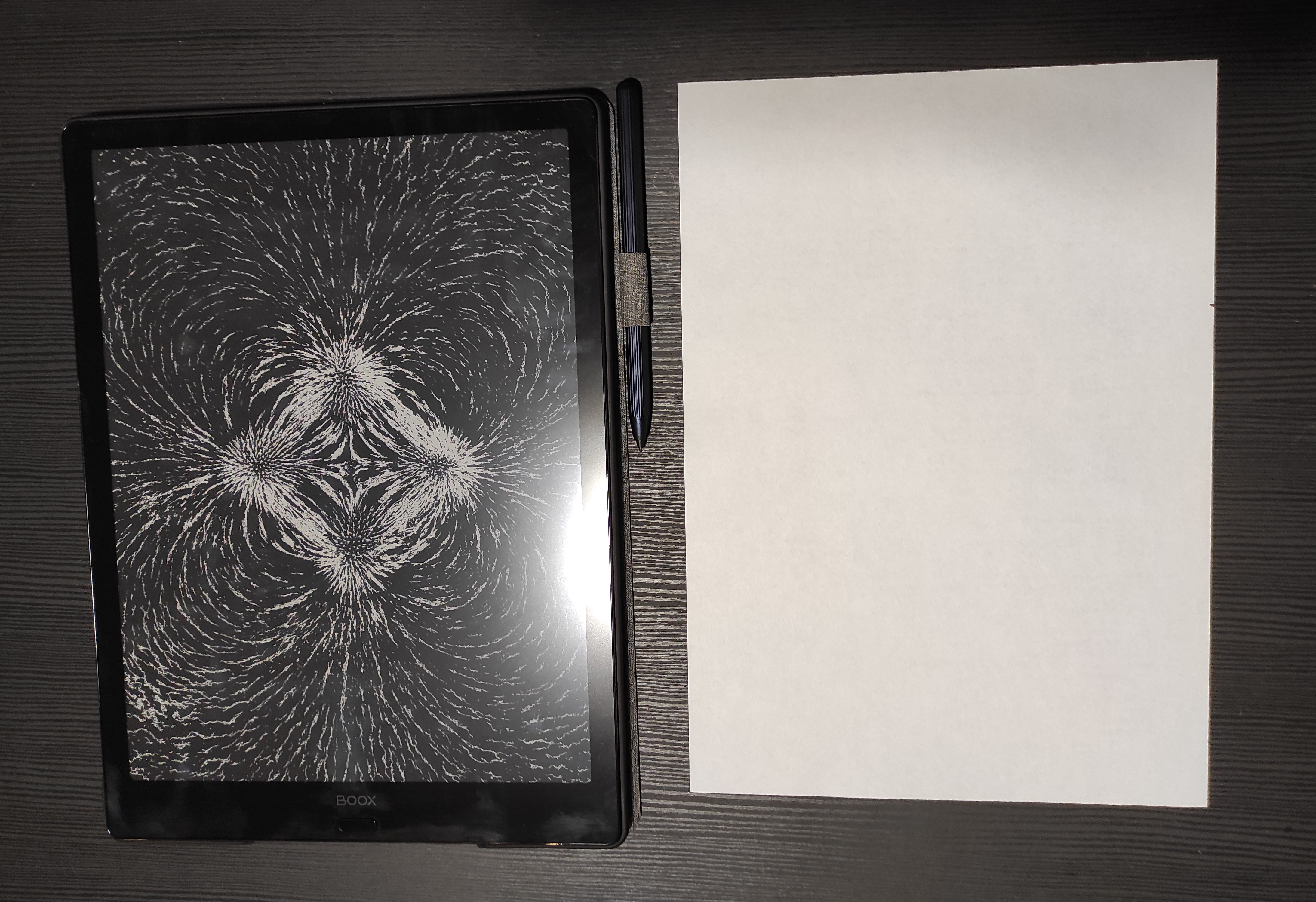

This is a 13,3" e-reader, which puts it almost to the size of an A4 paper. At ~900 USD it’s not a cheap device.

A4 paper for comparison. (Own work. License: CC-BY-SA.)

Hardware

Hardware-wise the device is great. The big e-ink screen is perfect for reading studies etc. pdf-format documents. The slight size deviation from A4 doesn’t matter in practice. You can adjust the backlight brightness and tone to your liking, or just turn it off and read in sunlight. There’s also a stylus which can be used to annotate documents, or you can just take a blanc paper and start drawing. Overall the device feels sturdy.

Software

The software solutions are a bit double edged. On one hand it runs Android, which is obviously better than any custom OS’. However, it’s quite heavily modified version of Android, and some of the choices are rather questionable. But of course Android isn’t going to work nicely on a slow black and white e-ink screen without some modifications, so lets keep that in mind.

The device has it’s own package repository, which contains some basic free apps. It’s possible to access Google Play but it’s not enabled by default, and the process is more complicated than just flipping a switch. Nonetheless it can be done pretty easily and it’s well documented.

The stock reading app is overall good and it sure has a ton of features, like cropping and annotating for example. One complaint is that turning a page requires a really long swipe. It’s like the distance would have been just scaled up with the screen size. (Of course you can turn a page other ways too.) The UI design is also little weird. The numerous features are hidden in different toolbars, in not particularly obvious way. But anyway the app gets the job done and you can download a different one if you don’t like it.

Similar UI oddities can be found elsewhere in the system as well. For example there’s a floating quickball enabled by default. Why on earth would I want some shortcut-smudge floating on the paper I’m reading? Luckily it can be disabled. The UI has an adhoc feeling to it. All in all I think that hiring one more UI designer wouldn’t have hurt. Or alternatively just making minimal modifications to stock Android to begin with.

Now one aspect that really is to my liking. The system exposes a lot of settings for tinkerers like me. Most notably there are a ton of settings about the screen and “colors”. And these settings really come in handy because 3rd party apps are typically designed for quick and colorful LCD displays, and look dark on e-ink. I like the settings, but I understand that they can be overwhelming if you’re the type of person who expects electronics to just work.

But Onyx doesn’t leave you alone with complexity. There is a brilliant documentation available here. IMO these kinds of comprehensive manuals are really underrated. I recommend scrolling through the document if you want to get a better idea of the available features.

To sum up

It’s great for reading PDFs. There are some shortcomings on the software side but it’s less of a problem because you have the freedoms offered by Android. You are given the tools to fix your own problems so to speak. That said, I’d expect a 900$ device to feel more polished.

Image is one of the bigger classic comic publishers. They are probably most know for The Walking Dead, but they publish a really wide range of comics. A lot of indie stuff included. Of course you can get their comics on print, but where they really stand out is the digital realm.

Image is one of the few comic publishers who offer comics without DRM. Though I should note that this does not cover their whole catalogue! (That’s why I dropped the fifth star.) They don’t have a dedicated online store but you can find their comics for example from Comixology. Just make sure to check the DRM-status before hitting buy!

Finally a couple personal recommendations from Image:

-

Lady Mechanika, the best steampunk series there is.

-

Monstress, a magical world shadowed by ancient Lovecraftian horrors.

As if Aidan didn’t already have his hands full! Now his father has gone missing. The single, unemployed dad of a highly energetic little daughter is barely out of bed when he begins to discover the first clues in his father’s workshop as to what may have happened.

What on Earth is “Clonfira”, and what do the strange patterns on the wall mean? Suffice it to say that Aidan’s father has discovered a way to visit another world, and Aidan and his daughter will soon follow in his footsteps.

The Little Acre by Irish indie developer Pewter Games is a point-and-click adventure. The game’s credentials are boosted by Executive Producer Charles Cecil, a grandmaster of the genre (Lure of the Temptress, Broken Sword).

Worlds brought to life

You play as Aidan and as his daughter Lily. The controls are as simple as it gets: you click on hotspots and sometimes combine items in your inventory with what’s currently on the screen. Many puzzles are contained within a single scene, keeping typical point-and-click frustrations (backtracking, a large inventory) to a minimum.

Most puzzles make sense at least in retrospect, even if you sometimes have to behave nonsensically to progress (scare a cat → cat smashes flower pot → smashed flower pot reveals hidden item you need). Built-in hints may help if you do get stuck.

Once Aidan enters the alternative dimension where his father may have gone missing, he transforms into a chibi (small and cute) version of himself. (Credit: Pewter Game Studios. Fair use.)

The game’s worlds are brought to life in excellent art and animation. Whenever you solve a puzzle, you’re likely to see a fully animated little scene. Even when you’re not doing anything, much of the game is visually captivating, and the world feels alive. Some cut scenes are almost of cinematic quality.

The game’s music is catchy and enjoyable, albeit a bit repetitive. The Little Acre is fully voice-acted as well. For some reason, the two main characters narrate their actions in the past tense, which doesn’t always make sense. There are no dialog trees and few interactions between characters.

A rushed adventure

It’s all over very quickly: a full playthrough is likely to take you between 1-2 hours. Some adventure games manage to deliver a powerful experience in a short playtime (think Loom or the more recent What Remains of Edith Finch). The Little Acre unfortunately feels very rushed.

Scenes that should have emotional power aren’t given the room they need. The villain’s motivations are insufficiently explained. A new character is introduced but given very little to do. Switches between Aidan and Lily happen too quickly. The ending is abrupt and delivers limited emotional payoff.

At the same time, the game’s amusing animations, cutely drawn characters, and relative simplicity make it a good family activity, if you don’t mind that it also deals with grief and loss. Kids may be more ready to forgive the game’s weaknesses, and to fill in the blanks with their own imagination.

Overall I would give The Little Acre 3.5 stars, rounded up because Dougal the dog is a very good boy. It’s often on sale for $5 or less, and that’s a good price to pay for it.

Technical notes:

The game has a native Linux version. It crashed for me a couple of times, but auto-saved at the beginning of each scene, so I did not lose any progress.

We. The Revolution is a fictionalised historical drama set during the Reign of Terror in revolutionary France. You play as an upstart judge, and with your ruling power, you will decide over life and death. Who is innocent? Who is counter-revolutionary? Who goes free? Who gets sent to the gallows?

During these uncertain times, you want to make it big, but you also have to protect your family, and yourself, of course.

The daily routine

The core gameplay loop revolves around different tasks that you have to do every day. You usually start with judging over a case in court, part-take in the execution (if that was your ruling), and manage relations with your family and friends. This is interspersed with the occasional story event. And over time, the daily routine gets more complicated. After a while, you even command a militia to defend and expand your territory within Paris. You even get the ability to plan conspiracies against your competitors for power over the city.

The court sessions are clearly the main attraction. You are given an investigation report regarding the person on trial. From this report, you can use the contained clues to unlock and extract statements from the defendant or a witness. Interestingly, you can choose which statements to pursue, and different ones will influence the jury’s opinion of the case. Theoretically, you could convince the jury that a totally guilty person is actually innocent just by choosing all the statements that paint them in a positive light.

Different sections of Parisian society will have expectations regarding your rulings. You will have to balance the goodwill of your family, the common people, the revolutionaries, and the aristocracy. If a faction gets too displeased with you, they’ll send an assassin after you—game over.

These groups are almost always at odds. There comes a point in the game where you always calculate the ramifications of your ruling beyond the defendant’s actual guilt. This is one of the very intriguing elements of the game. It shows you how you are just as much politician as other characters in the game, even though you are a judge by profession.

The brief good moments

Warning: The text below contains spoilers.

There are some great moments at the beginning of the game. They come about by the developers cleverly using established mechanics/moments in the game.

During chapter one, every time you let the guillotine blade fall, there is a gruesome scene afterwards, where a blood-soaked blade is strung up again, slowly overlooking a shocked crowd of spectators. Once chapter one ends, that scene is gone. The executions haven’t stopped—they have just become so commonplace they seize to be shocking.

Another such moment is when your son is murdered, you’ll receive a huge stack of condolence letters the day after on your desk during the trial.

Also great is when it is announced that imprisonment is not an option for punishment any more. Your options for rulings at this point are only freedom or the guillotine.

These small moments work well, and it is all the more intriguing to see how you climb the hierarchy of power in the game over time as your rivals get eliminated (often by you)—really showing how the Reign of Terror got its name. However, it is a shame how few of these moments are in the game overall—actually, I pretty much named them all.

Everything else

Huge parts of this game are clearly inspired by Papers, Please, which I remember as a focused and fun exploration of the game’s setting by playing a bureaucratic cog in the machine. We. The Revolution is not that. More and more responsibilities get added over time until the court sections seem like just another side attraction. It’s very unfortunate because while they don’t have much depth, they are the most interesting and deep aspect of the game. But as time goes on, you will spend more of it on positioning your militia on the map, convincing others to aid you in your conspiracies, and so on.

Over the hours of sticking with the game, I gradually lost interest. Once chapter three came about, I quit. The narrative revelation at the end of chapter two was simply not enough to keep me playing.

The only other positive thing that I can say about this game is that its art style is striking and fitting. Pixel art seems to be exhausted in its aesthetic capabilities at this point, so this mosaic art style was genuinely refreshing and looked great. It gives the game a simultaneously sharp but abstract look. Very fitting, I think, and I hope more games will use it in the future.

(Credit: Klabater/Polyslash. Fair use.)

Otherwise, the game gets bogged down by many weird technical issues. The game plays like a not so great mobile port. In fact, most moments in the game seem almost designed for a touch screen. I was surprised to find out this game wasn’t released on the iPad or a similar platform.

The game takes quite a bit of time to transition from one part of the daily routine to another, when really, for a 2D game, they should be instantaneous.

The UI has a weird bug where during questioning of a defendant you can’t fully scroll up the list of questions. Generally, the UI design is inconsistent and lacks indicators for navigation. More than once was I stuck in some menu for several minutes figuring out how to make the game do what I wanted it to.

Another thing regarding the UI: the text is really small, and there is no option for increasing the font size. To play this game on the Switch in handheld mode, I had to figure out how to use the Switch’s accessibility zoom feature.

Conclusion

I’m really let down. This should have been exactly my type of game, but its lack of focus and unnecessary technical quirks turn it into a test of patience instead of an exploration of the psychology of the leaders of a revolution during uncertain times. There are hints of a much better and good game present during chapter one, and it is a shame it can’t live up to any of that.

3/10

This is just brilliant offline dictionary app. It uses dictionary files generated from Wiktionary, so the data is top notch. The UI simple and straightforward. No bloat.

PS. If you ever need good dictionary-files, you can download the ones used by this app from here.

To the Moon (2011) is one of the most beloved indie narrative adventure games of all time. In it, two scientists travel into a dying man’s memories to fulfill his final wish. Into A Dream (2020), created by solo developer Filipe F. Thomaz, has a similar premise.

You play a man named John Stevens who finds himself in the dream world of another man, Luke Williams. Luke appears to be experiencing a mental health crisis, and you receive a message from the outside world tasking you with investigating its origins.

One of the unfortunate side effects of the dream insertion procedure is that John doesn’t have access to his own memories. So, just like the player, he knows nothing about the people he meets or the specifics of Luke’s life. John meets him and his family at different points in their lives.

Luke, it turns out, is an entrepreneur who is pursuing a vision of ubiquitous renewable energy. Exhausted by work, he reaches his breaking point after the early death of his mother. His wife Rita and his daughter Anne pay the price as Luke grows increasingly distant from them.

Platforms in the way

You view the dream world from its side, and everything is rendered in silhouette, as in a shadow play. As is typical for narrative adventure games, you spend a lot of time talking to characters you meet. The game also has simple platformer sequences (jump & climb), inventory fetch quests, and one puzzle that depends on precise timing.

The game’s action sequences and puzzles are rarely clever or original—they serve as speedbumps that prevent you from rushing through the story. Into A Dream lacks the qualities that make a great platformer (quick animations, optimized hit zones, responsive controls), so this is the single most frustrating aspect of play. Fortunately, you can’t die permanently, and you can save and resume anywhere.

Into A Dream makes excellent use of changing background colors, lighting, and other effects to convey the sense of an unstable yet beautiful inner world. The game is accompanied by Thomaz’ piano music, which suits the game’s atmosphere well. The presentation falls short in other ways.

When it doesn’t get in its own way, the game depicts a world that is suitably dreamlike, at times serene and beautiful, at times shockingly unstable. (Credit: Filipe F. Thomaz. Fair use.)

Inconsistent execution

Close-up views of objects (such as a children’s doll or a tombstone) look amateurish. Characters you meet are only rendered in one or two poses. For example, you’ll always encounter Luke’s wife sitting cross-legged or talking on the phone.

Animation is in short supply, too. Nobody other than you ever moves around—they just dissolve when a scene ends. The presentation gets in the way of the gameplay when you have to figure out what to do next: Where’s the exit? What’s that black object in the foreground? Can I interact with that door?

The game is fully voice acted by a diverse cast, at varying levels of quality: sometimes energetic, sometimes inaudible, sometimes overwrought or cartoonish. Given the game’s tiny budget (it raised less than $3,000 in an Indiegogo campaign), it would be unkind to be too critical here.

I found the story engaging, and the writing is generally good. There are a few spelling and grammar errors that could have been caught (such as the repeated spelling “murdured” instead of “murdered”), and a simplistic heaven/hell theme in the late game that distracts from the main story.

The Verdict

Into A Dream immerses the player in a world that is at times tantalizingly beautiful, but it frustrates them with clunky platformer sequences and immersion-breaking inconsistencies in its presentation. For a work mainly driven by a single developer, it’s an impressive achievement regardless, and I’ll certainly be interested in Thomaz’ future work.

I wouldn’t recommend Into A Dream at its full price of $15, but discounted below $5 it’s an interesting enough experience over 3 hours or so, if you’re willing to forgive its more frustrating parts. 3.5 stars, rounded down because of one especially annoying stealth sequence in the late game.