Reviews by Team: Nonprofit Media

We look for quality sources of news and analysis in the public interest

Jacobin is a New York based socialist quarterly magazine founded by Bhaskar Sunkara when he was 21 years old. It was started online in 2010 and is now also in print, with some content only available to subscribers of either edition. The website features news and analysis on an ongoing basis.

Sunkara is also a vice-chair of the Democratic Socialists of America, and he takes the “democratic” part seriously (“Any socialism we build will need to have a free, open civil society and multiparty democracy”, he recently tweeted). At the same time, you will find in Jacobin a perspective that is deeply critical of US mainline politics. On Bernie Sanders’ run, Sunkara predicted that Sanders would lose in the primaries, but that his run could be “an opportunity for movement building”.

In an interview with New Left Review, Sunkara articulated this focus on movement-building as core to his political philosophy: “What’s needed is to build movements until we reach a point where electoral options are actually viable.”

The organization behind Jacobin is a non-profit with about $300K in revenue in 2014. There is no Annual Report, which is not surprising for a tiny organization. In the aforementioned interview, Sunkara stated that most of this revenue is from subscriptions, with donations accounting for about 20% of the budget. In spite of its political radicalism, Jacobin is under conventional copyright terms (including back issues), and offers no discussion forums or other interactive components.

The print issue of Jacobin contains in-depth articles alongside beautiful graphic design (example issue). Unlike quite a few leftist magazines, Jacobin doesn’t engage in a lot of postmodernist piffle; its articles are often supported by charts and data, and tend to share a focus on issues that have real world relevance, including occasional departures into sci/tech themes like 3D printing or Silicon Valley politics.

So what can we find here that’s not reported elsewhere? Here are a few examples:

- an in-depth analysis of the prospects of the Kurds in Turkey, written by Djene Bajalan, an assistant professor with focus on Middle Eastern affairs

- a reasonable critique of Chuck Schumer, the prospective Democratic minority leader in the US Senate

- an analysis of the US media industry and the impact of the profit motive by Annenberg media studies scholar Victor Pickard.

One might wonder how a socialist magazine treats left-wing authoritarians. Will it applaud or rationalize as they restrict speech and political freedom, or will it criticize? The coverage of Cuban dictator Fidel Castro and Venezuela’s elected authoritarian Nicolás Maduro give us some idea. The Jacobin Castro obituary is in fact one of the better ones I’ve read, and is unambiguous in its criticism, for example:

“It was relatively simple to dismiss the calls for democracy from internal critics as imperialist propaganda, rather than a legitimate claim by working people that a socialism worthy of its name should transform them into the subjects of their own history. Public information was available only in the impenetrable form of the state newspaper Granma, and state institutions at every level were little more than channels for the communication of the leadership’s decisions.”

“An opaque bureaucracy, accountable to itself alone, with privileged access to goods and services, became increasingly corrupt in the context of an economy reduced to its minimal provisions. Castro’s occasional calls for ‘rectification’ removed some problem individuals but left the system intact.”

It concludes that “any socialism worth its name needs a deep and radical democracy.”

Jacobin’s coverage of Venezuela’s dysfunctional, corrupt and increasingly authoritarian government has been less robust and more likely to look for justifications primarily in the behavior of the right-wing opposition, though the article “Why ‘Twenty-First-Century Socialism’ Failed” by Venezuela-born socialist Eva María offers a more critical perspective which echoes the commitment to worker-focused democracy that defines Jacobin’s politics:

“The party, however, did not rely on its members’ active participation no matter how much Chávez liked to say it did. Instead, a bureaucratic structure, where criticism, open debates, and rank-and-file power were more often the exception than the rule, took over. The party formalized the bureaucratic layer of nominal Chavistas who were put in charge of different state sectors. In no time, this new caste engaged in corrupt behavior while continuing to deploy socialist rhetoric. The government’s ideas of funding and supporting popular power didn’t work in practice.”

The Verdict

Operating on a tiny budget, Jacobin offers a much-needed, intellectually coherent journalistic challenge to the prevailing social and economic order. The pitfalls of its political position are easy to pinpoint: the history of socialism and communism is riddled with failed economies, brutal autocrats and centralized bureaucracies, which calls into question whether its aspirations can ever be achieved in practice.

To build a mass movement for democratic socialism in the United States may seem like the remotest of possibilities, but the political successes of Bernie Sanders and the failure of the Democratic party to protect the progressive gains it has made under the Obama administration will lead many young people to search for alternatives.

Whether Jacobin can be a leading voice of that search for alternatives (within the two-party system, or outside mainline politics) will largely depend on whether it can maintain its commitment to a vision of radical democracy, consistently oppose political violence, and overcome any impulse to jump to the defense of authoritarian leaders who share some political objectives. The left is not immune to group polarization, and unreconstructed old-school socialists who habitually defend the indefensible are the political anchor around its neck.

I recommend Jacobin with reservations: read critically, it offers a useful complement to anyone’s diet of news and analysis. It is also aesthetically pleasing and edited with care, and their Twitter account is a good way to follow their work. 3.5 out of 5 stars, rounded up.

Founded in 2005 as a simple multi-author blog (Wayback Machine copy), ThinkProgress has grown into one of the more popular progressive news sites, with an estimated reach of 1.8M monthly uniques per Quantcast. Behind it is a powerful NGO with strong ties to some prominent players in US politics.

Organizational Structure, Funding

You may have never heard of the Center for American Progress, but it’s one of the most well-funded political nonprofits in the US, with over $45M in revenue in 2014. It was founded by none other than John Podesta, chair of Hillary Clinton’s 2016 presidential campaign and victim of a phishing attack of likely Russian origin on his email account.

CAP’s funding comes from foundations, corporations, individual major donors, and small donations. Its “Supporters” page provides a breakdown, and says that “corporate funding comprises less than 6 percent of the budget, and foreign government funding comprises only 2 percent.” Big foundation funders include the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the Ford Foundation, the Sandler Foundation, and George Soros’ Open Society Foundations.

CAP has a sister organization, the Action Fund. Unlike CAP, it is organized under the 501c4 section of the US tax code which permits political lobbying, but means that donations are not tax-deductible. It is a smaller organization, with about $8.5M revenue in 2015, the single largest chunk of which comes from CAP itself. The organizations also share the same CEO, Neera Tanden.

The Action Fund is the organization behind ThinkProgress, which is said to be fully editorially independent. Founder and editor Judd Legum left ThinkProgress in 2007 to join Hillary Clinton’s presidential bid as research director and then returned to his role, which is an example of the revolving door from CAP to the US Democratic establishment.

In 2015, Legum received total compensation of $199K from the organization, which is comparable to other nonprofit publications like Mother Jones.

Transparency

The ThinkProgress website is one of the worst we have reviewed in terms of disclosing organizational internals. The About page mentions its parent organization without even linking to it. There, with some luck, you may find the list of supporters; beyond that, the only reporting I was able to find on the organization’s work was a 10th Anniversary Report (and only with Google).

Considering the combined revenue of the two organizations, this is a remarkably poor level of transparency; much smaller organizations like Truthout manage to report regularly about their own work (reports) and make these reports easy to find.

Positioning, Bias

ThinkProgress describes itself as dedicated to “providing our readers with rigorous reporting and analysis from a progressive perspective”. Beyond that positioning statement, does it have bias toward specific politicians or policies?

Using the 2016 election as a yardstick, political connections notwithstanding, I did not find evidence of bias in favor of one of the Democratic candidates (Bernie Sanders or Hillary Clinton) in the coverage itself. Privately, the Wikileaks disclosures show that ThinkProgress editor Judd Legum did sometimes casually forward items of interest that could be used against Sanders (emails that include Legum and Sanders).

One exchange in particular caught the attention of right-wing critics. It was a heads-up by Legum that Faiz Shakir, a former ThinkProgress staffer, had started doing some work for the Bernie campaign. CEO Neera Tanden (Legum’s boss) reacted in a manner that can only be described as vitriolic.

It would be unfair to infer too much about ThinkProgress itself from these leaked private exchanges. They only serve to underscore the strong personal connections of some of its key players to the Clinton campaign. Now that the campaign is lost, it remains to be seen how these same players act in the changed political environment.

I would describe ThinkProgress editorially as left-of-center, which in the age of Trumpism makes them a useful source of adversarial journalism. Its content selection reflects a progressive perspective that is relatively free of reflection and squarely directed at the political right. In pursuing this agenda, the site sometimes overstates/sensationalizes slightly, but not as much as clickbait sites like Occupy Democrats do; more on this below.

Stories do appear to go through internal fact-checking (though the editors fell for a fake news site in 2014).

The site also engages in independent fundraising from readers, e.g., for its recently launched Trump Investigative Fund.

Content Examples

Consistent with its origins as a blog, ThinkProgress does not distinguish between news, analysis, or commentary. Some of its reports are in-depth investigative journalism that would be right at home on sites like ProPublica (e.g., its report on the growth of the sanctuary city movement since Trump’s election).

An example article that shows reasonable depth, while also not presenting any perspective that disagrees with its analysis: “Trump poised to violate Constitution his first day in office, George W. Bush’s ethics lawyer says”. See this NYT piece for a somewhat more balanced assessment of the same situation. This is a case where citing only a single perspective serves to slightly sensationalize reporting.

Similarly, when 46 US Attorneys were fired by the Department of Justice, ThinkProgress focused on framing the action as part of a larger purge narrative, not spelling out that Bill Clinton fired all 93 attorneys in 1993 (see the Vox reporting). This is an example of using a fairly ordinary political event as a “hook” to support a larger narrative.

As an example for overstating, one article calls the war in Yemen a “climate-driven war”. While the article itself makes good arguments, that summary overstates the role of climate change (compare this analysis by International Policy Digest).

Sometimes the site does use clickbait tactics. The headline “SCOTUS nominee Neil Gorsuch faces extraordinary sexism allegation from former student” uses ambiguous language which could describe a wide range of behaviors in order to sensationalize Gorsuch’s alleged comments about maternity leave.

Worse, these comments are disputed by several other students (see NPR coverage, or National Review for the right-wing perspective). This isn’t mentioned in the article, and ThinkProgress kept tweeting the piece at least until March 24, when other media had already reported the dispute.

Design, Licensing

ThinkProgress design in 2005, 2011 and 2017 (old screenshots courtesy of archive.org).

The ThinkProgress website is a branded version of Medium, with all the associated advantages and disadvantages (e.g., it works poorly without JavaScript, but looks nice on mobile and has decent built-in social features such as commenting, notifications and following).

Content is under conventional copyright, with permission to re-use granted on a case-by-case basis.

The Verdict

While I would not put it in the same journalistic category as publications like Mother Jones or The Intercept, I do recommend following ThinkProgress on Twitter or by other means as a source of progressive advocacy journalism. At its best, ThinkProgress provides valuable in-depth investigative reporting.

The complex influence web behind CAP and the parent organization of ThinkProgress raises questions about how autonomously it can operate, but one shouldn’t overstate the case. The organization it is not dependent on a single funder and relies on public support, as well. Perhaps ThinkProgress would better served being a truly independent organizational entity, which would also enable tax-deductible donations.

The rating is 3.5 stars, rounded down. Points off for a slight tendency toward sensationalizing (primarily through framing and selective reporting) and a lack of transparency.

(Updated in March 2017 with new information and to be more consistent with our review methodology.)

Democracy Now! is one of the best-known progressive news sources in the United States. It has been around since 1996 and is distributed online as well as through broadcast television and radio. It is identified strongly with co-founder, principal host and executive producer Amy Goodman, an investigative journalist known for courageous confrontations with powerful economic and political forces. Most recently, Amy Goodman was in the news because an arrest warrant was issued against her in connection with her reporting on the Dakota Access Pipeline. The case was quickly dismissed but helped bring further attention to the protests.

The organization running the show is a non-profit, though it does not appear to publish an Annual Report (none is listed on the website, and an email request has so far not been answered). Its revenue for 2014 was $6,674,958, so the lack of transparency about impact, strategy and spending is a bit unusual for an organization of this size. Indeed, Charity Navigator rates it at two stars for accountability and transparency, due to the lack of audited financials or information about its board of directors.

The primary content the organization produces is a Monday-to-Friday one hour broadcast (in English, with some content translated to Spanish) that typically consists of news and interviews. With a progressive lens, the show gives more attention to issues that typically only get second-tier coverage in mainstream media, such as international efforts to combat climate change, or left-wing social movement activism. This is done in a dry and muted “just the facts” tone.

The show is always smart, sometimes tedious (interview guests are hit or miss; breaks with music or monotonic monologue are not for everyone), sometimes engaging (like when it tackles challenging conversations, such as discussions about third party candidates).

An example of clever journalism, even if one disagrees with it: during the 2016 election, Democracy Now! staged a reenactment of one of the US presidential television debates, giving third party candidate Jill Stein (who was not permitted to participate) the opportunity to answer the same questions the main candidates were asked. (The libertarian candidate was also invited, but could not make it.)

The overall curation of topics is quite remarkable, and the emphasis on stories not receiving attention by major media makes Democracy Now! a good addition to any news and information mix, if the video/audio format works for you. There is textual content on the site, but much of it is transcripts or very short blurbs.

Personally, I prefer to read the news, as do young people who have grown up with the web. But the Democracy Now! broadcast reaches audiences who may not be deft navigators of the web, and therefore is an important part of the US political media landscape.

The online version of the show does offer links to different segments and transcripts so you don’t have to watch to or listen to the whole show. But of course content that is native to the web offers many other possibilities that are underutilized in a TV/radio show transported to the web – conversation and participation, interactive data and charts, cross-referencing, embedded videos, tweets and other content, and so forth. This also gives Democracy Now! a disadvantage in social media that rely on content that’s optimized for being shared.

The Verdict

Democracy Now! is a fine example of viewer-supported journalism. It is constrained by its format and perhaps to an extent by its ambition. It is a brainy daily roundup that appeals to people who already self-identify as progressive, but is unlikely to convince people who are not. Many will background the broadcast to other activities rather than intently listening for an hour (a podcast version is available).

The lack of organizational transparency is disappointing for a non-profit, though not surprising for an organization that’s clearly monomaniacally focused on its mission. In spite of those reservations, Democracy Now! deserves four stars for its tireless dedication to quality journalism and to the pursuit of major stories and topics that are neglected elsewhere. Even if you don’t identify with the (by US standards) far left political lens of the broadcast, including frequent spotlighting of third party candidates, it enriches our perspective on the world in ways other sources rarely do.

Truthout is a progressive news site that’s been around since 2001 and is run by a non-profit organization. Their most recent tax return shows about $1.4M in revenue. Most of that goes to salaries and most of which comes from small donations. I was impressed with their annual report which highlights some of the stories they’re proudest of – it’s very professionally done, even though the organization is much lavishly funded than, say, ProPublica.

They highlight their climate disruption dispatches, their reports from Ferguson, and their investigation into the anti-trafficking movement (which they call the American Rescue Industry) as examples of their best reporting.

In practice, the Truthout front-page offers original content alongside syndicated pieces from sources like Democracy Now! and FAIR. A significant part of Truthout original content is news analysis and opinions. If that’s your cup of tea, you’ll find some good reads here; personally, I’d prefer a stronger focus on news and investigative pieces.

The perspective here is progressive-left, but it stays away from conspiracy-mongering and clickbait. At a time when sites like “Bipartisan Report” and “US Uncut” offer stories that are often half-true or sensationalized, Truthout offers a rational alternative. That said, the site is simply too small to serve as a primary news source; I do recommend following it as a secondary one.

The Verdict

Let’s compare it with Common Dreams, which is quite similar in its political bias and focus. Common Dreams has a more vibrant discussion community, and it licenses its content Wikipedia-style, free for anyone to build upon (Truthout uses conventional copyright terms). I find Truthout’s content to be higher quality and their organizational transparency to be up to the standards of a well-run non-profit. I gave Common Dreams three stars; I’ll give Truthout 3.5, rounded down for now since there’s still quite a gap to larger non-profit efforts.

Mother Jones (MoJo) is a progressive magazine and website, and yet, when it came to the candidacy of Bernie Sanders in the 2016 US presidential election, they were one of the more consistently critical publications.

They kicked things off in 2015 by digging into Sanders’ 40-year-old writings (when he was in his 20s), highlighting anything that could be scandalized, and wrapped it up by calling him a con man. No, that was not enough, even after Sanders endorsed Hillary Clinton and began campaigning on her behalf, Mother Jones titled: “Don’t Hate Millennials. Save It For Bernie Sanders.”

In fairness, most of those stories were written by one of MoJo’s most prolific commentators, Kevin Drum, who on the other end filed stories like “Hillary Clinton Is Fundamentally Honest and Trustworthy”, “Hillary Clinton Is One of America’s Most Honest Politicians”, and “New Email Dump Reveals That Hillary Clinton Is Honest and Boring”.

I personally don’t see much value in a progressive news source engaging in trivial commentary to elevate an establishment candidate running, literally, a billion-dollar campaign, while belittling and dismissing her progressive opponent. It’s after half a dozen such stories that I stopped paying attention to MoJo for a while.

But one shouldn’t assess a news source based on the work of a single contributor. Other parts of MoJo did break more critical stories, such as “Hillary Clinton and Henry Kissinger: It’s Personal. Very Personal.” and “Hillary Clinton’s Goldman Sachs Problem”, both by David Corn. That’s the same man who broke the story “SECRET VIDEO: Romney Tells Millionaire Donors What He REALLY Thinks of Obama Voters” during the 2012 election, arguably the most influential single story in that campaign.

The currently featured investigations include a four-month undercover report about a private prison that MoJo rightly compares to Nellie Bly’s pioneering work in the 19th century to uncover abuses in New York’s Women’s Lunatic Asylum. This is the kind of journalism that’s incredibly hard to find and deserves kudos.

In other words, while I sometimes would wish for more depth and rigor, and less participation in rationalizing the status quo, it would be unfair to not acknowledge that MoJo is still a pretty remarkable publication that can pack a punch. I’m not a subscriber or donor, but I do read it from time to time.

The Foundation for National Progress is the nonprofit behind Mother Jones magazine, with a pretty diverse funding model that includes grants, subscriptions, donations and advertising. As of 2012, ads made up only 13% of the overall revenue.

ProPublica has become almost synonymous with a new nonprofit approach to investigative journalism. There are three major reasons for this:

- It was born digital in 2007 (unlike veteran organizations like the Center for Investigative Reporting, which has been around since 1977).

- It received $10M of seed funding and continued support from liberal billionaires Herb and Marion Sandler, instantly making it one of the most well-funded journalism nonprofits.

- It was the first online news source to receive the prestigious Pulitzer Prize, and has since received two more Pulitzers, and many other awards.

Positioning

Propublica describes its mission as follows:

To expose abuses of power and betrayals of the public trust by government, business, and other institutions, using the moral force of investigative journalism to spur reform through the sustained spotlighting of wrongdoing.

It claims to take no sides:

We do this in an entirely non-partisan and non-ideological manner, adhering to the strictest standards of journalistic impartiality.

ProPublica’s focus is primarily on the United States. Beyond that single constraint, its mission gives it a very broad mandate.

Financial Origins

As noted above, the project would not exist without the Sandlers. Herb and his late wife Marion made their money with Golden West Financial, which they purchased in 1963 and sold in 2006 to Wachovia, reportedly making $2.4B from the sale. They dedicated $1.3B to the Sandler Foundation, which has so far given $750M to many causes ranging from political (John Podesta’s Center for American Progress) over human rights (Human Rights Watch) and environment (Beyond Coal) to science/medicine (UCSF Sandler Neurosciences Center).

The role of Golden West, which also operated under the name World Savings Bank, in the 2007-2008 financial crisis is a subject of considerable dispute. Unsurprisingly, right-wing critics who seek to discredit ProPublica refer back to this history, such as this detailed, characteristically conspiratorial analysis by Glenn Beck’s The Blaze.

What’s clear is that Golden West was a portfolio lender, meaning it didn’t engage in the selling and re-selling of debt under cryptic names such as “collateralized debt obligations”. Many experts view this “securitization of loans”, and the false positive ratings obtained from rating agencies, as central to the financial crisis (an interpretation popularized by the movie “The Big Short” based on Michael Lewis’ book of the same name).

In the heat of the crisis, the practices of GW/WS did come under intense media scrutiny, especially given the sale of the company to Wachovia – which subsequently underwent a government-forced sale to Wells Fargo in 2008. The article “The Education of Herb And Marion Sandler” by the Columbia Journalism Review is an in-depth summary, which concludes that some of the criticism of the Sandlers was unfair and overwrought (Saturday Night Live revised a skit that called the Sandlers “people who should be shot”). The CJR article also recapitulates evidence that some mortgage brokers employed by GW/WS did employ unethical sales practices.

Nonetheless, the Sandlers were long-time advocates for ethics and integrity within the banking industry, and in fact founded the Center for Responsible Lending in 2002, which has been a strong advocate for regulatory reform, including for the creation of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau.

In short, a review of the evidence suggests that it is unfair to paint the Sandlers as villains of the crisis, or to make any a priori assumptions about bias in ProPublica’s reporting based on their philanthropic support for the project.

Early History and Executive Compenstion

ProPublica is based in New York City. Herb Sandler was the first Chair of the Board (he is now a regular trustee). Its founding editor, Paul Steiger, was previously managing editor of the center-right Wall Street Journal, which was acquired by Rupert Murdoch’s News Corporation after Steiger’s departure. Given the Sandlers’ support for progressive causes, the hire may have been intended to send a strong signal that ProPublica would be impartial and not an activist project.

Steiger’s initial compensation by ProPublica was $570K (plus $14K in other compensation such as insurance), as a Reuters blog reported under the sardonic headline “Philanthrocrat of the Day”. Outside public broadcasting, this is easily the highest executive compensation among any of the nonprofit publications we’ve reviewed.

In 2015, the year of the most recent available tax return, Steiger was Executive Chairman (a part-time role) and received $214K. President Richard Tofel received a total of $421K, Editor-in-Chief Stephen Engelberg received $430K, while a senior editor typically received $230K in total comp.

This is still high compensation, especially for the two top jobs. For comparison, in the same year, the CEO of Mother Jones (a San Francisco based journalism nonprofit with comparable revenue) received total comp of $195K, while DC bureau chief David Corn received total comp of $175K.

Why does this matter? Executive compensation ultimately speaks to the organization’s use of donor money (more money for executives means less money for journalists), as well as to the hiring pool it considers for key positions. Above-sector compensation may predispose it to seeking top hires from for-profit media, as opposed to building internal and sector-specific career paths.

It is difficult for organizations to change established compensation practices, but as we will see, ProPublica is relying more and more on public support, so it is reasonable to ask questions about these longstanding practices.

Transparency, Revenue

Compared with many other organizations we have reviewed, ProPublica’s level of transparency is excellent. (There’s no strong relationship to compensation or revenue: We have found very small organizations that are great at this, and very large ones that are terrible.)

ProPublica has published 7 Annual Reports and 14 shorter “Reports to Stakeholders” about its work. Its 2016 report was published in February 2017, which is very timely. The organization also makes its tax returns and financial statements easy to find.

For 2016, ProPublica reported $17.2M in revenue, of which most came from major gifts and grants ($9M/52.5% from major gifts/grants of $50K or more, and an additional $3.7M/21.8% from Board members).

$2.1M/12.5% came from online donations. That seems like a small share, but it’s a massive increase compared to the previous year, when ProPublica reported only $291K in online donations.

This bump in donations is, of course, due to the election of Donald Trump, which led to a surge of donations to many nonprofit media – aided, in ProPublica’s case, by a shoutout on John Oliver’s news/comedy program Last Week Tonight.

Measuring Impact

ProPublica’s reports have always focused on trying to make the connection between its reporting and real-world impact. The impact page captures the highlights from these reports.

On the positive side, it is highly laudable that the organization makes efforts to monitor long term consequences. For example, in its 2016 report, it notes:

A 2010 ProPublica investigation covered two Texas-based home mortgage companies, formerly known as Allied Home Mortgage Capital Corp. and Allied Home Mortgage Corp, that issued improper and risky home loans that later defaulted. Borrowers said they’d been lied to by Allied employees, who in some cases had siphoned loan proceeds for personal gain. In December a federal jury ordered the companies and their chief executive to pay nearly $93 million for defrauding the government through these corrupt practices.

Monitoring what happens after a story is published, following up repeatedly, is a big part of what characterizes excellent investigative journalism.

On the negative side, the impact reports are almost unreadable – they’re long bullet point lists without any meaningful structure or even links to the articles they reference, and without a larger narrative to connect them.

In 2013, ProPublica published a whitepaper called “Issues Around Impact” that describes robust internal tracking processes. For example:

ProPublica makes use of multiple internal and external reports in charting possible impact. The most significant of these is an internal document called the Tracking Report, which is updated daily (through 2012 by the general manager) and circulated (to top management and the Board chairman) monthly.

The whitepaper includes some samples of these tracking spreadsheets, but they are generally not made public. Is that the right call? I don’t know, but I do think that it’s worth thinking about ways to make the overall ongoing impact monitoring more public and more engaging.

Content Example: “Machine Bias”

Machine Bias is a good example for how ProPublica tackles large investigations. Major topics are organized in series, and the Machine Bias series comprises 25 posts ranging from major stories to brief updates. The series examines the increasing role algorithms play in society, from online advertising networks to the criminal justice system.

It’s a complex topic, and the first major article in the series, also titled “Machine Bias” and published in May 2016, is no exception. It focuses on software developed by Northpointe (recently re-branded Equivant) which aids judges in assessing the likelihood that a given criminal offender will commit crimes again when released into the general population.

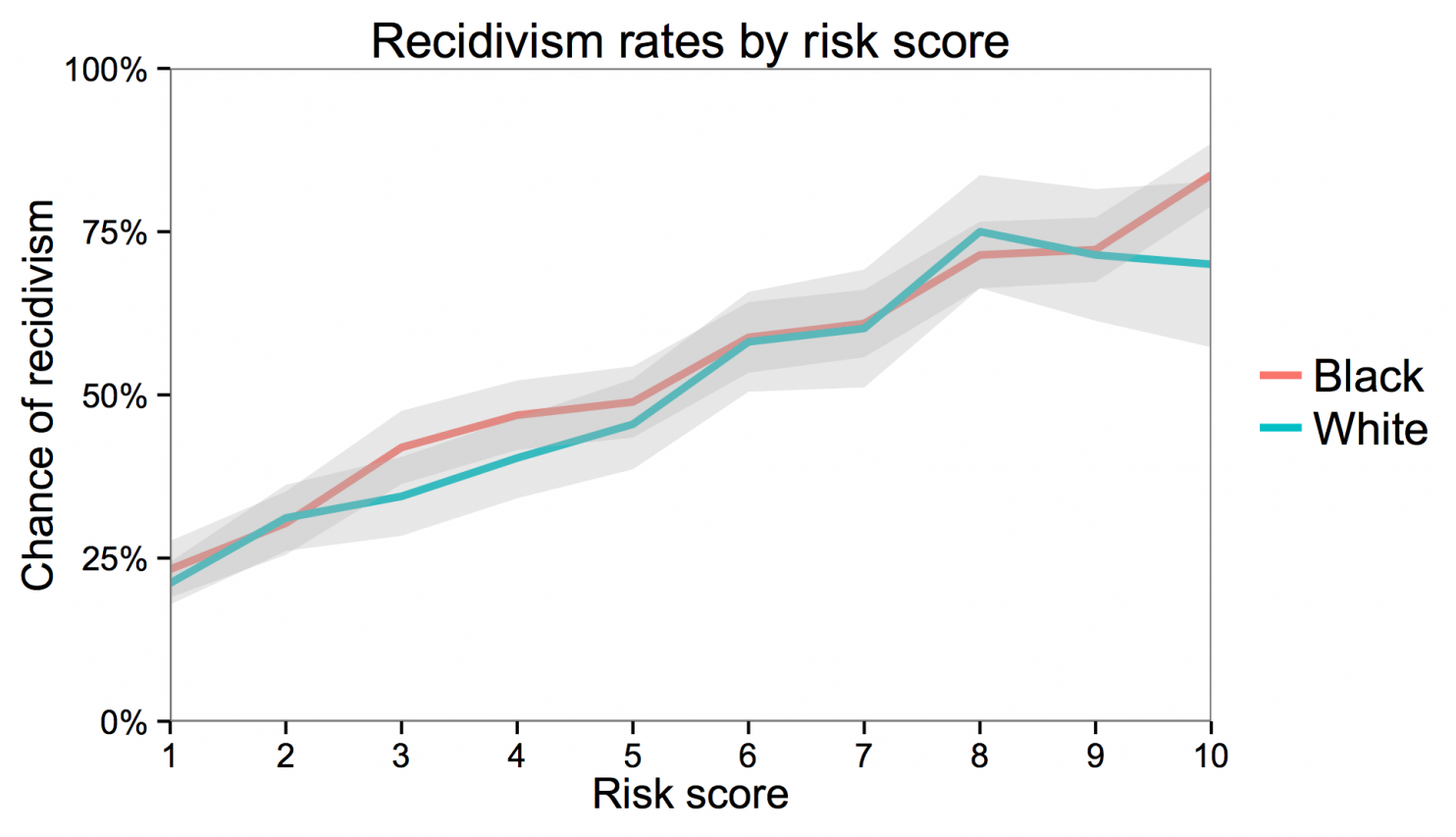

These risk assessments may end up influencing everything from sentencing to parole conditions, even though the system is not meant to be used in sentencing. ProPublica asserts that the system is biased against black defendants. According to its findings, the rate of false positives (% of non-re-offenders who were falsely labeled higher risk) is nearly twice as high for black defendants as for white ones (44.9% for blacks vs. 23.5% for whites), while for white defendants, the rate of false negatives (% of re-offenders who were falsely labeled low risk) is much higher (47.7% for whites vs. 28.0% for blacks).

The company behind the tool strongly disputed the findings. ProPublica published several follow-ups, including a detailed technical response to Northpointe’s criticism. Ultimately, as a Washington Post follow-up blog post by a team of researchers explained well, much of the disagreement boils down to your definition of fairness.

In the study’s sample, African-Americans have a higher recidivism rate (likelihood to commit another crime after being arrested). That means that even if the algorithm is “equally accurate” at predicting recidivism, it will be wrong for a larger absolute number of African-Americans, and therefore for a larger share of the total number of African-American offenders. From an individual African-American’s perspective, you’re more likely to be falsely flagged as high-risk than a white person.

The analysis by a team of independent researchers summarized in a Washington Post blog shows that both Northpointe and ProPublica have a point. A risk assessment can have comparable predictive value between racial groups, but have disparate (unfair) impact on one of them.

Evaluating ProPublica’s article

ProPublica’s article sheds light on a phenomenon known as disparate impact. More black people than white people receive unfair treatment through many systems or policies, such as Northpointe’s risk assessment tools, because of long-standing population-level differences in arrest rates, poverty, economic access, and so on. This feeds a vicious cycle that limits opportunities and exacerbates racial stereotypes.

The Northpointe algorithm is based on a questionnaire that includes questions such as “How many of your friends/acquaintances have ever been arrested?”. Regardless of its predictive value, this is the type of question that contributes to racially disparate impact: According to the Sentencing Project, the likelihood for white men to be imprisoned within their lifetime is 1 in 17, and for black men it is 1 in 3.

It should be noted that ProPublica argues in its analysis that the algorithm’s bias extends beyond the base rate difference. In its technical notes, it states that “even when controlling for prior crimes, future recidivism, age, and gender, black defendants were 77 percent more likely to be assigned higher risk scores [for violent recidivism] than white defendants.” If true, this speaks to persistent bias beyond what would be expected of an “equally accurate” algorithm.

ProPublica does not attempt to compare the accuracy and fairness of Northpointe’s approach with any other risk assessment method, automated or not. Obviously, to judge whether the system should be used and improved or abandoned, that’s a very important question. But ProPublica makes no assertions beyond the system’s disparate impact and does not sensationalize its findings. Northpointe may feel that it is being unfairly singled out, but demonstrating problems by way of specific examples is in the nature of investigations like this one.

The organization of the investigation into a series, with repeated follow-up and reasonable presentation of disagreement, speaks to tenacity and systematic thinking required to achieve meaningful change. The inherent complexity of the subject would pose a challenge to anyone; the original article makes noble efforts to penetrate the numbers with examples and storytelling, but in my opinion falls a little short in that regard.

In spite of these limitations, there is little doubt that the article has stimulated important debate, follow-up research, and even meaningful action. As ProPublica reported, Wisconsin’s Supreme Court ruled, citing ProPublica’s work, that warnings and instructions must be provided to judges looking at risk assessment scores. And a follow-up scientific investigation by Kleinberg, Mullainathan and Raghavan explained the fundamental mathematical tradeoffs in designing systems that are fair to populations with different characteristics.

ProPublica’s article is also a good example of what’s called data journalism. Beyond the ordinary qualifications of journalists, it relies on in-house statisticians and computer scientists to investigate a topic. This is not without its pitfalls, since such work does not pass through traditional scholarly peer review, while mistakes in stories like this one can be highly consequential.

ProPublica consulted with experts on the methodology and code used for its analysis. It made all internals of the analysis available, including through an interactive notebook on GitHub which anyone with statistical knowledge can use to replicate the findings. This shows a great level of care, though the sector as a whole might benefit from a more formalized review process when tackling data analysis of this complexity.

The “Machine Bias” series (which beyond the article reviewed here includes, e.g., an investigation into racial targeting of Facebook ads) received a Scripps Howard award.

Content Example: Investigating Trump, Obama

Since the election of Donald Trump, ProPublica has aligned more of its resources to cover the Trump Administration. In addition to a dedicated section, the writers and editors have prioritized several topic areas of increased public interest. These include hate crimes and extremism, health care, immigration, and influence peddling (per Trump’s campaign promise to “drain the swamp”).

Most of the Trump-related articles are shorter pieces such as “Trump’s Watered-Down Ethics Rules Let a Lobbyist Help Run an Agency He Lobbied”. In some cases, ProPublica calls on the public for help with its investigations. For example, it released a list of 400 Trump administration hires and invited public comment on them.

Given ProPublica’s claim of nonpartisanship, it’s worth asking if the site applied similar scrutiny to the Obama administration and the major policy themes of Obama’s two terms. Early in Obama’s first term, the site launched promise clocks to track Obama’s promises, though it’s unclear if the project was abandoned – for example, the promise clock to repeal the anti-gay “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” policy in the US military is still ticking, even though the policy was in fact repealed.

It investigated the use of stimulus funds in detail through an “Eye on the Stimulus” section, and dedicated a series to Obamacare and You, which tracked, among other subjects, the disastrous initial HealthCare.gov rollout, as well as problems with state-level exchanges. It also pursued in-depth investigations on promises such as Obama’s pledge to fight corporate concentration.

Whatever ProPublica’s blind spots, they don’t appear to be partisan. Its strength tends to be domestic reporting that touches ordinary people’s day-to-day concerns. In contrast, only a handful of articles cover topics such as the US arms industry and weapons sales to authoritarian regimes, or US involvement in Yemen’s bloody war. When major scandals break, such as Edward Snowden’s revelations about the NSA spying program, ProPublica does contribute its own coverage, but national security and foreign policy are clearly not its core expertise.

Newsletter, News Curation

Like most nonprofit media, ProPublica has an email newsletter. It’s pretty conventional and highlights the top stories of the day with brief abstracts. It includes some clearly labeled sponsored content.

A dedicated section called “Muckreads” is meant to highlight investigative stories from around the web. I say “meant to highlight” because it’s not been updated in recent weeks. The format also takes some getting used to: the page is simply a collection of tweets.

To its credit, ProPublica’s work over the years helped cultivate the #MuckReads hashtag on Twitter, but the project could use a kick in the behind or a reboot. Two counterexamples that may offer some inspiration:

- The newsletters of The Marshall Project (which focuses on criminal justice) do an excellent job of combining original and curated content in an engaging format.

- Corrupt AF is a recently launched site that curates stories related to (in the maintainer’s estimation) corruption in the Trump administration. It uses a similar “wall” format to Muckreads, but affords considerable space to excerpts and highlights.

Other Projects

ProPublica has a long history of starting projects that go beyond conventional journalism, including interactive databases and trackers. For example, its Surgeon Scorecard reveals complication rates about surgeons (an approach that’s not without its detractors).

It also maintains a database of nonprofit tax returns, and has taken over several projects from Sunlight Labs, after the Labs were shut down by the Sunlight Foundation, a pro-transparency organization. For example, ProPublica is now maintaining Politwoops, a database of deleted tweets by politicians.

The nerd blog logs new releases and updates to existing “news apps”, and code is generally published to ProPublica’s GitHub repositories. Still, with large databases like the Surgeon Scorecard, it would be useful to have clear commitments as to how frequently the data will be updated – or to officially mark them as unmaintained when that’s no longer the case.

ProPublica also asks for public involvement in many of its investigations, often by way of surveys (“Have you been affected by X? Tell us how”). An attempt to use Reddit to let users pitch story ideas has been abandoned.

Design, Licensing

ProPublica in 2008, 2011, and 2017. Its core site design has not changed significantly over the years.

ProPublica is nearly a decade old, and it shows. As I reviewed it, I encountered pages with broken layout, a page that threw an error message, pages that were prominently linked but inactive or abandoned, and old news apps that no longer worked as intended. It’s easy to get lost in the site’s fluctuating taxonomy of projects, tags, series, and investigations. The frontpage is cluttered with various buttons and boxes. The news feed on the front page combines internal blog posts (hiring announcements, awards, etc.) with major investigations.

It’s understandable that the site has shied away from major design reboots. There are a lot of moving pieces, and it would be easy to accidentally break older content. Still, site design and information architecture deserve more attention than they have received.

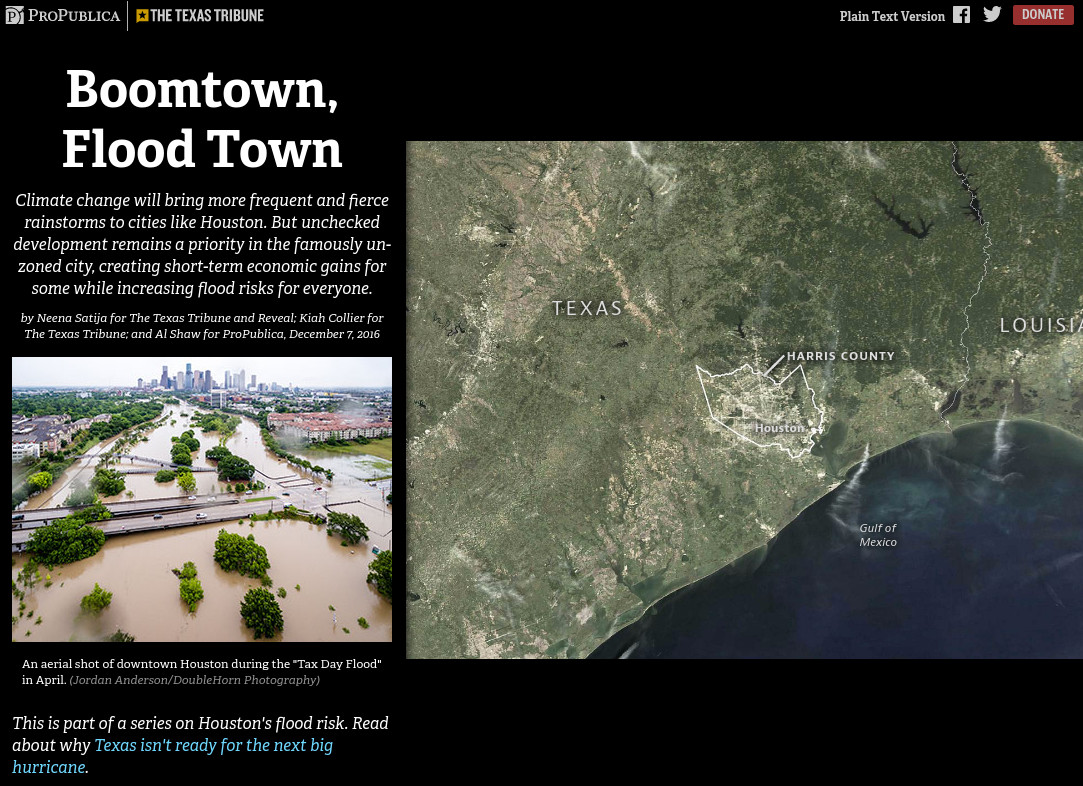

In fairness, individual stories sometimes get a lot of design love. Investigations like Boomtown, Flood Town are little micro-websites that are a joy to use (and that have deservedly won awards). Much of the site works well on mobile devices. In an age of ever-disappearing comment sections, it’s also nice to see that ProPublica hasn’t killed its own, and the signal-to-noise ratio of comments is not terrible.

It’s worth noting that many of ProPublica stories are jointly published in other traditional news media. Its content is also available under the Creative Commons Attribution/Non-Commercial/No-Derivatives license, which allows limited re-use. The consequence is that in spite of ProPublica itself not being to most engaging news destination, the impact of its stories is far greater.

Individual stories, such as “Boomtown, Flood Town”, somtimes have carefully built micro-sites. This one won a design award, as did several others.

The Verdict

Let’s break down the formal rating:

- Journalistic quality: ProPublica does excellent journalistic work and has been deservedly recognized for it. I’ve seen no evidence of manipulative intent; ProPublica may sometimes overstate its case a little bit, but generally follows up on criticism and posts updates and corrections.

- Executive compensation: ProPublica’s executive comp is well above average for the sector. Given its increasing reliance on small donations, it loses 0.5 points here.

- Wastefulness: There’s no significant evidence of waste, but a spring cleaning of abandoned or low-impact projects/services may free up some resources.

- Transparency: ProPublica’s organizational transparency is exemplary. Its approach to tracking and reporting impact is well thought-out, but could be more engaging and accessible.

- Reader engagement: In spite of some stellar story-specific design work, there’s definitely significant room for improvement when it comes to the main site’s design, discoverability of content, usefulness of the email newsletters, and technical maintenance of the site. ProPublica loses 0.5 points here.

Stepping away from the formal rating, ProPublica has published some remarkable investigations over the years which have positively impacted people’s lives. Its investigations have targeted large banks, airlines, state and federal government, hospitals, doctors, schools, nonprofits, and many others. As such it plays a vital watchdog role in US society.

I haven’t seen evidence that its funding sources drive its story selection, but this would be difficult to prove. Increasing the share of small donations is the best way to guarantee ProPublica’s independence, and it will require the aforementioned improvements in reader engagement.

ProPublica’s approach is least suited to addressing system-level failures: economic inequality, corporate tax evasion, climate change, mass incarceration, money in politics, LGBT discrimination, etc. That should not be held against it, as it is a somewhat inherent limitation of its mission. That’s where nonprofit media with a more specialized mission shine: InsideClimate News for climate change, The Marshall Project for mass incarceration, the Center for Public Integrity for money in politics, and so on.

The final rating is 4 out of 5 stars: recommended. You can follow ProPublica on social media (Twitter, Facebook), or via our Twitter list of quality nonprofit media.

(This review was rewritten in March 2017 to be brought in line with our review criteria. The score did not change.)

Common Dreams has been around since the late 1990s. It’s a non-profit news website that’s featured contributors like Noam Chomsky, Molly Ivins, Robert Reich, Howard Zinn, and other voices of the political left in the United States. It is funded exclusively by small donations from its readers, which means you’ll occasionally see Wikipedia-style fundraising banners among the content. Indeed, Common Dreams uses the Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License, the same license used by Wikipedia.

Typically, you’ll find opinions and analysis that are aligned with the Green Party and the far left in the US. The site’s relatively small budget means that some reader discretion to double-check sources is advised, and the quality of writing and editorial selection varies. At the same time, the site is relatively free of conspiracy theories and is a good source for alternative news especially on environmental issues and civil rights in the US.

The Common Dreams Commons is a surprisingly active forum (running the open source Discourse software), but unfortunately does not set itself apart from the comment sections of other news sites in meaningful ways.

Common Dreams rarely get major scoops, but it’s worth following them on Twitter (and perhaps making a donation once or twice a year) to get an additional perspective that unskews some of the selection biases of larger for-profit media.

The Intercept is a well-funded online news source, part of Pierre Omidyar’s post-eBay adventures. Led by editor-in-chief Betsy Reed, it is co-edited by Glenn Greenwald (who, with Laura Poitras, broke the story about NSA mass surveillance driven by Edward Snowden’s leaks) and Jeremy Scahill (Dirty Wars).

Given Greenwald’s and Scahill’s experience, it is perhaps unsurprising that national security, the intelligence apparatus, and foreign policy are key focus areas for The Intercept, which it tackles with investigative reporting, analysis and commentary. One of its biggest stories was the release of the Drone Papers, which debunked the myth of precision that is associated with drone warfare.

Beyond that, it covers a range of subjects that fit the broad mandate of its staff to “bring transparency and accountability to powerful governmental and corporate institutions.” It provided extensive coverage of the 2016 US presidential election, and it has reported in-depth on criminal justice issues and immigration.

In addition to the English language version that focuses on the United States, there is also a Brazil edition in Portuguese. Greenwald is based in Brazil, and the decision to launch a Brazil edition isn’t part of some strategic master-plan, but came organically out of his reporting.

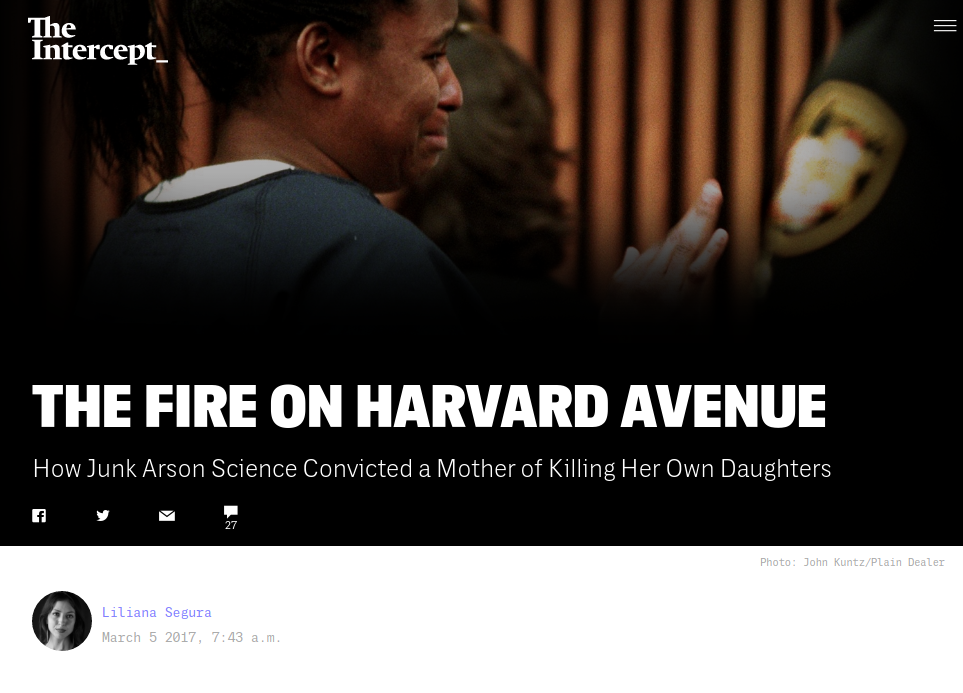

A typical feature story. While many stories are focused on national security, intelligence, and foreign policy, The Intercept covers an assortment of subjects, including in-depth criminal justice investigations like this one.

Organization, Executive Compensation

The Intercept is part of First Look Media, a nonprofit organization founded by billionaire philanthropist Pierre Omidyar, who made a public commitment of $250M to the organization in 2013. Through its 2015 tax returns, First Look Media disclosed $34.6M in total revenue and an allocation of $9.1M of expenses specifically to The Intercept.

First Look also funds the documentary series Field of Vision and co-financed Spotlight, an Oscar-winning 2015 movie about the Boston Globe’s investigation into child abuse by Roman Catholic priests.

The Intercept editor Elizabeth Reed received $300K in total compensation in 2015, which is in the mid-range of similarly well-funded nonprofits. In any event, since The Intercept has so far not asked for donations from the public, executive compensation is a secondary concern.

First Look Media has had its share of growing pains. In 2014, a project to be headed by Matt Taibbi fell apart with his noisy departure; in 2015, staff reporter Ken Silverstein had a very public falling-out with the organization, alleging managerial incompetence; in 2016, writer Juan Thompson was fired for making things up, and in 2017, Thompson was arrested for bomb threats against Jewish Community Centers.

In fairness to the organization, it has consistently and, as far as I can tell, truthfully reported about these internal issues (though an independent ombudsman role might give such reports greater credibility). In contrast, First Look Media does not provide much conventional nonprofit transparency: no Annual Reports or other disclosures beyond the legally required ones; no publicly evident attempt to measure or report its impact. Its approach to accountability is journalistic, not organizational.

Positioning, Bias

The Intercept’s pursuit of what it terms “adversarial journalism” leads it frequently to go after stories other publications are less comfortable with. For example, it recently published an in-depth report from Yemen about a US anti-terror raid which killed up to 25 civilians including nine children under the age of 13. In contrast, most US media tend to focus on US losses in military confrontations.

During the 2016 US presidential campaign, The Intercept writers echoed many pundits by predicting that Hillary Clinton would likely win the election. “Get Ready to Ignore Donald Trump” wrote Zaid Jilani, while Robert Mackey maintained a live blog called “The Trumpdown” with the subtitle “Our Long, National Nightmare Is (Probably) Almost Over” (the subtitle has since been changed to “The Decline of Western Civilization: The Bannon Years”).

The Intercept pursued adversarial stories about both frontrunners (Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton), while many media gradually transitioned into largely getting behind one of the two candidates (newspapers which endorsed a candidate supported Clinton by a 19:1 ratio). Many observers argued that the greater number and severity of scandals associated with Trump (and the greater threat he represented to the country) deserved greater attention than a politician with fairly ordinary flaws like Hillary Clinton.

Greenwald defended his approach in an interview:

“I just reject pretty vehemently the premise of the question, which is that paying attention to Hillary Clinton’s most significant question marks somehow undercuts the journalistic attention that has been paid to all of Trump’s question marks. I can pretty much point to every single aspect of Donald Trump’s personal, political, and financial life — it’s been dissected by great length and with great skill by the investigative reporting teams of the Wall Street Journal and the New York Times and Washington Post.”

The Intercept and Wikileaks

Whatever one thinks of the reasoning, there is little doubt that The Intercept’s coverage was heavily influenced by the strategic timing of Wikileaks releases about the Clinton campaign. The Intercept reported about the leaks without hesitation, generally staying away from conspiracy theories and focusing more on Hillary Clinton’s paid Goldman Sachs speeches or the US relationship with Saudi Arabia. In contrast, it largely ignored or downplayed claims of Russian involvement in the hacks which made these disclosures possible.

Unlike other publications like VICE and Ars Technica, it didn’t report about the in-depth public investigations by SecureWorks which showed that the phishing attacks that targeted the Democrats also targeted Russian journalists and other targets of interest to Russian intelligence, and that the attacks could be linked to a group that has been identified with Russian intelligence before. Only after the election, it published a comprehensive summary of the available evidence, calling it “not enough”.

While skepticism about far-reaching claims and theories regarding Russia/Trump collusion was and is certainly appropriate (and The Intercept rightly called out the Washington Post for credulously promoting an amateurish blacklist of “pro-Russian” news sources), the publication may have undermined its own case by overdoing it.

In contrast, The Intercept rarely reported critically about Wikileaks itself. Even when Wikileaks fed the most bizarre conspiracy theories, it was left to the Washington Post to debunk them. Many other falsehoods or mischaracterizations sourced to Wikileaks received little attention from journalists while spreading like wildfire.

Given their combined expertise dealing with sensitive materials, here was an opportunity for Intercept reporters to help readers interested in the leaks by separating nonsense from reality, and to call out Wikileaks’ active participation in the fake news pipeline. It was an opportunity The Intercept did not take.

Greenwald’s “adversarial journalism” appears to translate to an almost singular focus on a narrow set of powerful players, driven by a default set of assumptions about where abuses of power originate.

Content Example: “Agonies of Exile”

The Intercept regularly publishes photojournalism features. Agonies of Exile is one such feature which focuses on deported mothers of children who can stay in the US under the DACA policy, one of the few immigration reforms Barack Obama was able to implement.

The intro is succinct (a bit overly so), and the photographs are moving. While it is a good piece of photojournalism, one look at the comments should quickly destroy any hopes that such storytelling alone will change hearts and minds. But it may help.

Content Example: “The FBI’s Secret Rules”

This series of articles is based on a set of internal FBI documents obtained by The Intercept which detail rules and regulations for FBI operations and investigations. Each article in the series focuses on specific practices, e.g., the payment of informants, and is supported by annotated source documents.

One has to be pretty interested in law enforcement practices to digest the whole lot, much of which quickly devolves into subtle arguments about whether specific loopholes in the rules allow for abuse or not. For example, the article “Hidden Loopholes Allow FBI Agents to Infiltrate Political and Religious Groups” reveals an FBI that is genuinely struggling to strike the right balance between civil liberties and security.

That is not to say the investigation isn’t important – it is, and it’s precisely through this type of public accountability that rules are improved and abuse is constrained. But judging by the single digit number of comments on most of these stories, it’s clear that there’s considerable room for improvement in how the material is organized and presented.

This begins with the landing page itself, which is honestly a bit of a mess. It attempts to use the FBI manuals as a way to section the series, which is neither engaging (who is drawn in by the words “Confidential Human Source Policy Guide”?) nor immediately apparent. As you move your mouse across the page, huge background images from each story strobe into view in a frustrating and disorienting manner.

The landing page of the investigation is a bit of a mess, especially once you start trying to navigate it.

The individual stories range from mundane to significant. The stories about how the FBI works with informants reveal a troubling set of incentives ranging from huge payments – some coming out of seized assets – to deportation threats, and efforts to conceal the reality of what’s going on. This is an example of a story that, with more focused attention, might have been developed into an engaging feature.

In general, fewer stories (there’s a total of eleven) and a more focused approach might have served the topic better. Alternatively, highlighting the major stories of an investigation (as ProPublica does with all its larger series) would make the content easier to navigate and reveal the editors’ own sense of the relative importance of each story.

In spite of these criticisms, the stories tackle an important set of subjects, are diligently researched, well-sourced, and offer multiple perspectives where appropriate, including from the FBI itself.

Design, Licensing

The Intercept has a minimalist design that puts stories and photographs front and center. I wouldn’t exactly call it beautiful (unless monospace terminal aesthetic is your thing) but it is distinct without getting in the way, at least when it comes to individual stories. The site’s top-level story sectioning is essentially useless, providing categories such as “Top Stories”, "Unofficial Sources, “Glenn Greenwald” and “Recently”.

The site employs a navigational paradigm where the web address changes when scrolling down, as different stories (from the main feed or one of the sections) are loaded. This makes it easy to accidentally lose one’s place, though I’ll grant that it aids random, low-effort exploration of the site’s content.

There’s a comment section below each story. It is powered by an odd homegrown commenting system that appears to have received minimal technical attention. It neither requires nor permits any form of authentication to verify one’s identity. Because The Intercept attracts a fair number of cranks, the signal-to-noise ratio is mediocre at best, though comments appear relatively free of spam and abuse.

(Update December 2017: The Intercept switched its discussion system to Coral Talk, bringing with it major changes to functionality and moderation, including a requirement to create a user account. We’ll update this review once the new system has been in use for a while.)

Content is under conventional copyright, with an email address for case-by-case re-use permissions. First Look Media also has a small GitHub presence that is not prominently advertised and mostly used for internal tools.

The Verdict

The Intercept describes our world through a darkened lens. In its editorials, it seeks to frequently assure its readers that the cynical, suspicious view of the world is the only rational one to take. The 2016 election showed the limits of this approach, when the publication’s contrarianism regarding increasingly evident meddling by bad actors – including, most likely, Russian intelligence – through leaks and disinformation was covered by The Intercept in ways that were often less informative than the reporting of mainstream sources.

It is understandable, then, why the site provokes strong reactions, but regardless of these limitations, its in-depth journalistic investigations often shed light on subjects that others ignore, which makes them undeniably valuable. It is obvious that Intercept reporters are given the time, freedom and resources to pursue these challenging stories. As the “FBI manuals” example shows, while The Intercept does not always succeed in making complex topics engaging, it’s clear that the team strives to be thorough and ethical in its reporting.

No other nonprofit journalism source we’ve reviewed is as strongly identified with a single personality – in this case, Glenn Greenwald. The Intercept has not yet developed an institutional voice, style or journalistic approach beyond Greenwald’s, and it feels very much like an extension of his beliefs and values. This, combined with its funding model, may put The Intercept on shaky ground when it comes to its long term future.

In spite of the criticisms above, I give The Intercept high marks for the overall quality and value of its journalism. I subtract a point for the lack of organization-level transparency, and for sometimes going off the contrarian deep end in ways that serve neither truth nor justice. We need The Intercept, but we also need it to be better. 4 out of 5 stars.

(March 2017: Rewritten to provide more detail & color, and to be consistent with our review criteria.)