Reviews by Eloquence

Paradigm is an indie point-and-click adventure game developed by Jacob Janerka and available for Linux, Mac, and Windows. The premise is pretty straightforward: You’re a mutant with a tumor head and a moribund electronic music career, living in an abandoned town in a post-apocalyptic Neo-Soviet Eastern European country; you gradually discover that you are at the center of a conspiracy orchestrated by an anthropomorphic sloth genetically engineered to vomit candy. Okay, maybe not that straightforward.

In spite of the Eastern European-ish setting, most of the game’s cultural influences are Western: classic movies like Star Wars and Rocky, the LucasArts adventure games, Futurama, YouTube series, Australian shows and bands, and so on. The game’s developer, artist and designer, Jacob Janerka, is Australian of Polish origins, and the game is very much a reflection of what’s in his head.

Above all else, Paradigm is a classic adventure game made by someone who clearly loves and respects the genre. The game largely avoids the pitfalls that can make adventure games frustrating: illogical puzzles, deaths, dead ends, or pointless walking around.

When you’re stuck, you can even ask your own tumor for tips. You’re unlikely to need to: The game follows a fairly linear progression with mostly item or dialog-based puzzles. If you feel like it, you can take detours to discover mini-games and various hidden objects.

Mini-games, you say? Yes, but they’re not the usual tic-tac-toe level bullshit. Instead, it’s stuff like:

-

a post-apocalyptic dating simulator;

-

the game of Boosting Thugs, styled like a 16-bit beat ‘em up, but instead of fighting your enemies, you give them compliments;

-

audio cassettes spread throughout the game, containing choice content like a live belly-slapping performance.

In a half-serious adventure game like Broken Age, almost all content you find throughout the game is part of a puzzle. But in Paradigm, much of it is just there for the hell of it—you can ignore it, or have fun with it, making the attention to detail here all the more remarkable.

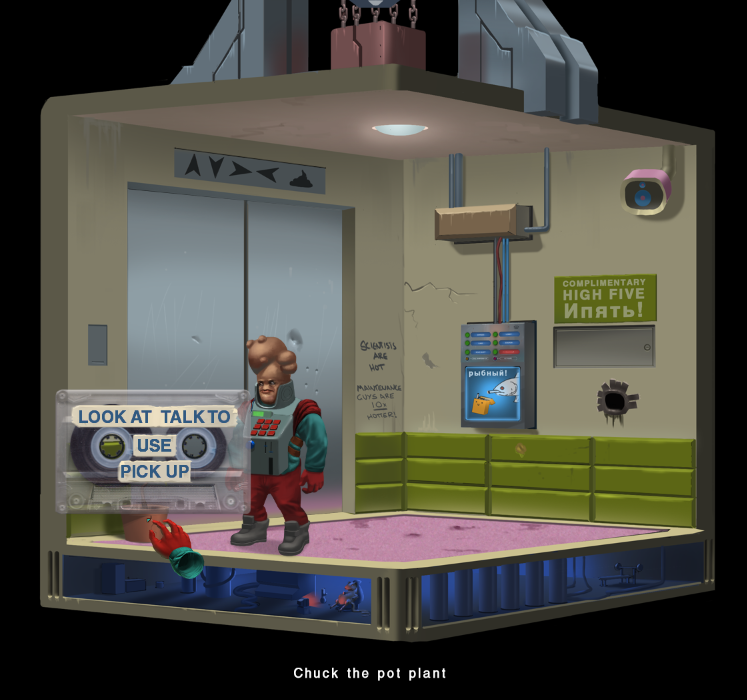

Paradigm, the main character, spends a fair bit of time in this elevator. Note the rat watching TV and the tiny rat gym, and the reference to Chuck the Plant from Maniac Mansion. (Credit: Jacob Janerka. Fair use.)

The game’s controls are reminiscent of later LucasArts titles like Full Throttle and Grim Fandango: you have a few interaction verbs that you can access through a pop up menu, giving maximum screen real estate to the game’s graphics. At different points in the game, you get access to a map for quick navigation.

Janerka did the much of the work on the title as a one person studio (the music was composed by Jonas Kjellberg) and funded the project’s completion via Kickstarter. Of course, parts of the game lack polish, and a lot of the humor is at the dad joke level and can be a bit cringe-inducing. That said, I laughed out loud a few times, so the batting average isn’t all that bad.

I played Paradigm for a total of about 8 hours, during which I looked at the walkthrough a couple of times. I paid about $5 (discounted price on GOG, currently it’s back up to $15). Even at $15 you’re likely to get good value for your dollar; if you see it at a lower price and enjoy point and click games, I would definitely recommend it.

Lutris is an all-in-one game management tool for Linux. It lets you organize your installed Linux-native games from sources like GOG or Steam, but also integrates various console emulators (from ZX Spectrum to PlayStation 3) and optimized configurations for running various Windows-only title under Linux using Wine.

Lutris is fully open source, community-maintained, and funded via Patreon (as of this writing, about $600 a month—hopefully more by the time you read this). The graphical client integrates nicely with its own game database on the web.

After you install Lutris, you can choose which “runners” you want to enable—e.g., you can choose to turn on the PlayStation 3 “runner”, after which Lutris downloads and installs the required emulator automatically (Lutris maintains its own build infrastructure to create builds of the latest releases). If a game is not in the Lutris database, you can still add it to your collection through the UI.

Through this functionality, Lutris fills an important gap in the Linux gaming ecosystem. To understand why, it’s important to look at the story of Linux gaming so far.

A brief history of Linux gaming

Early efforts to port games to Linux (Loki Entertainment, 1998-2001) or to run Windows games on Linux directly (Cedega, 2004-2009) failed commercially. For a while, it looked like Linux gaming would remain the domain of die hards who are happy with open source games like Battle for Wesnoth, emulators, and the occasional Linux port.

But today, Linux gaming is not just back, it’s thriving. There are several reasons for that:

-

Cross-platform development is the norm for popular titles, not the exception (porting to/from mobile, to/from consoles, etc.), and common game engines like Unity and Unreal support Linux.

-

Online stores like Steam, GOG and itch.io treat Linux almost as a first class citizen and have dramatically lowered the cost of distributing Linux versions (compared with putting boxes on shelves, but also with game developers maintaining their own distribution channels).

-

The stores themselves have a financial interest in seeing games ported to Linux. And while Valve’s Linux-based SteamOS project seems to be going nowhere, the company continues to invest in Linux compatibility through projects like Steam Play.

All of this means, however, that Linux gaming is still heavily dependent on commercial players who tend to favor keeping gamers within their ecosystems, and whose commitment to Linux is either constrained or entirely driven by profit motives.

While Steam is available for Linux, it’s proprietary and employs DRM; GOG’s recently launched “GOG Galaxy” application is also proprietary and, as of this writing, Windows-only. Running emulators for other platforms within the Steam client is possible, but not a first-class feature. And let’s not even talk about the proprietary nature of the metadata and reviews.

A gaming platform fit for Linux

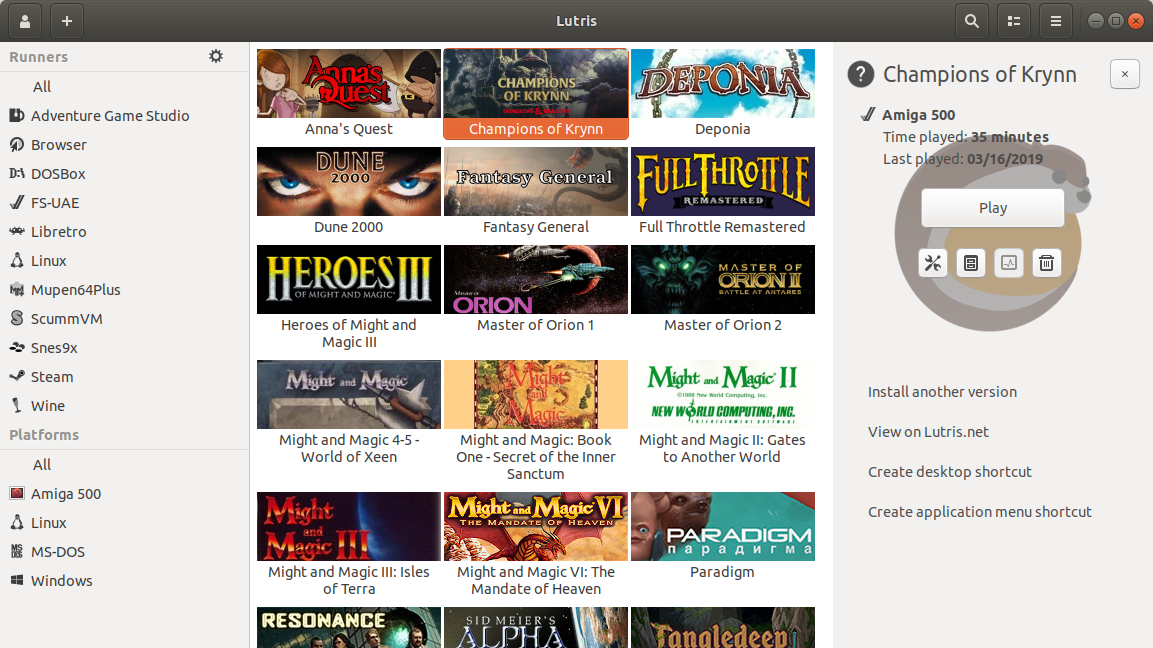

Lutris has the feel of a project that really fits into the Linux ecosystem. Open to all comers, after a few minutes of setup, you may have a gaming library that looks like this, where Linux native games live alongside games run under Wine, DOSBox, or FS-UAE (an Amiga emulator):

The Lutris user interface showing a set of games using different “runners”. (Credit: Lutris developers and various game development studios. Fair use.)

If a game isn’t in the Lutris database and not Linux-native, you may still have to go through a fair bit of trial and error, and it may not work at all. There’s less polish and more of a DIY feel to all of this: Lutris doesn’t protect you from doing things that won’t work, while a platform like Steam does its best to ensure the user always gets what they paid for.

All aspects of Lutris are open to community contributions—you can suggest changes in the game database, submit your own “runners”, or your own install scripts for specific games. And with at least a modest amount of Patreon funding, the project hopefully won’t just disappear (if it does, there’s still Phoenicis, the designated successor to PlayOnLinux).

The verdict

I’ll keep using Lutris to organize my own Linux games, and I’ve joined the project’s Patreon as well because it feels worth supporting. Whether the project is ultimately successful likely depends on whether it can grow a vibrant community of contributors: not just of runners and installers, but also of game metadata and contributions to the client.

I encountered a few rough edges using Lutris (the experience importing games you’ve installed from GOG is still fairly manual; I ran into a few 404s in the game database; the per-game preference dialogs are a bit nightmarish), but overall it’s already saved me a fair bit of time getting some Windows games to run without futzing around too much. And I’m happy to trust the judgment of the Lutris community to find the best emulator for a certain platform or game.

The database of games on Lutris.net is its own ambitious project, and it might benefit from integration with Wikidata and perhaps even use of the Wikibase software instead of its own custom change management tooling; it also currently doesn’t have a clearly stated license.

As a whole, Lutris is currently the most promising effort of its kind. If you’re a Linux gamer, I recommend taking a look at it, along with more narrowly focused projects like Lakka (a Linux distribution just for retrogaming) and the aforementioned Phoenicis.

Imperial Twilight: The Opium War and the End of China’s Last Golden Age is an attempt by American historian Stephen Platt to explain the causes of the First Opium War (1839-1842) between the United Kingdom and China under the Qing dynasty, and to contextualize it in the history of the declining Celestial Empire.

Platt is a gifted storyteller, and the book puts significant focus on individual actors. It begins with the story of British merchant James Flint’s ill-fated 1759 expedition to change the conditions under which British traders operated; it ends with the protagonists of the First Opium War, such as Foreign Secretary Lord Palmerston, Chinese anti-drug official Lin Zexu, and William Jardine, one of the leading opium smugglers.

Platt also tells us about some of the domestic threats the Chinese empire was facing during this era: on land, the White Lotus Rebellion that combined political grievances with religious fanaticism; at sea, a formidable united pirate fleet known as the “Red Flag Fleet”, commanded by a female leader, Ching Shih. The Qing dynasty’s ineffective response to these threats is symptomatic of the “imperial twilight” of the book’s title.

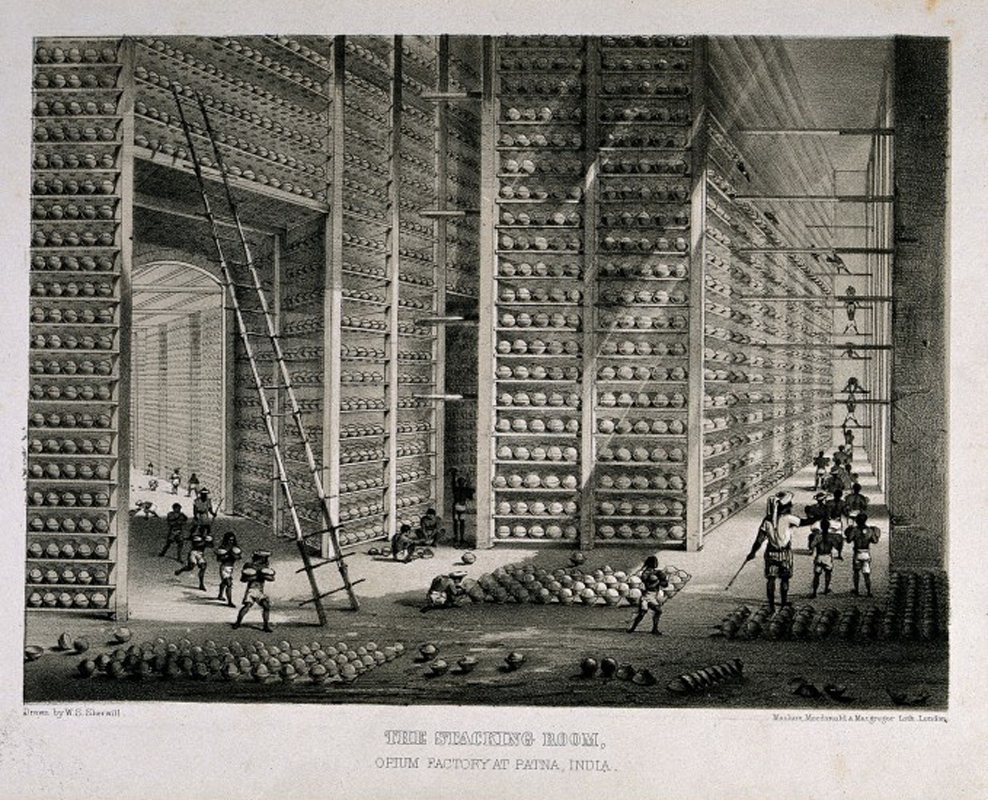

Stacking room at an opium factory in Patna, India (1850). (Credit: W. S. Sherwill. Public domain.)

Wars for drugs

The foreign opium trade itself had its roots mainly in India, where the East India Company controlled much of its production. Platt explains how the explosion of production and trade turned a luxury drug into a major national health problem for China and drained the domestic economy of silver that was used to pay drug dealers.

After largely unsuccessful efforts to police Chinese traders and users (and a tantalizing flirtation with the idea of legalization), the empire appointed an official named Lin Zexu to a position we might today call a drug czar. Lin cracked down on the the foreign traders who brought opium into the country; he blockaded their ships, seized their opium, and ordered the destruction of more than 1,000 tons of it.

Although no British subjects where physically hurt in this confrontation, the destruction of property—even property whose sale was very much illegal in China—provided a casus belli for the First Opium War, leading to the first of the unequal treaties between China and European powers (and soon, to the Second Opium War).

If you ever wondered why Hong Kong was a British colony until 1997: it was one of the spoils of Britain’s drug wars. These wars forced China to accept the opium trade, and cleared the path to respectability for those who sold the drug. Today, Jardine Matheson, which was originally built on the opium trade, is a $39.5B conglomerate.

Agency and empire

Platt’s central thesis is that the war could have been averted if just a small number of individuals had acted differently: there was significant opposition to the opium trade within Britain; many traders were perfectly happy to play by China’s rules; Lin Zexu overplayed his hand against the British; his British complement, trade superintendent Charles Elliot, made an absurd promise to compensate the opium smugglers that forced the hand of the British government.

It’s a fine hypothesis, but I don’t buy it. The British Empire’s political structure was designed to find accommodations between power factions, with 86% of adult men and 100% of adult women disenfranchised. The legal and illegal traders who wanted to force an opening of China (with preferential treatment for Britain) were an increasingly powerful faction. Britain was aware of China’s inability to defend its coastline.

Sooner or later, a similar combination of means, motive and opportunity would have led to a similar criminal undertaking. This is not an argument against culpability or agency of individuals. But I believe Platt’s view of China is a lot more realistic than his view of the politics of the British Empire.

The verdict

Platt’s book spends almost no time writing about the First Opium War itself, which was, after all, a war in which around 20,000 people—mainly Chinese—were killed or wounded. He says the bare minimum about the Second Opium War, about the concessions China was forced to make to Western powers, about the consequences for ordinary Chinese people.

Nonetheless, this is an insightful, well-researched and highly captivating book. I especially appreciated the author’s efforts to convey the frequent cultural misunderstandings between British and Chinese diplomats and politicians, which heavily contributed to the failure to find common ground peacefully. The book also contains many beautiful black-and-white illustrations and helpful maps.

Stephen Platt’s book is a piece to the puzzle of a history that seems especially important today. China is re-emerging as a superpower—perhaps the superpower—while nationalist rhetoric is back in fashion in Western democracies. If you’re looking for a definitive or systematic history of the Opium Wars, this isn’t it. But if you’re looking for a book that will draw you into the world of the traders and smugglers, scholars and fools in which those wars took place, I recommend Imperial Twilight unreservedly.

Sigmund Freud (1856-1939) is a man often credited with a lot of things: with discovering or “unlocking” the unconscious mind; with exposing a prudish and trepidatious society to the power of sexuality; with boldly and creatively speculating about the meaning of dreams, the neuronal basis of behavior, the origins of religion, the drive towards self-destruction.

That view of Freud is one which is conveniently separated from his life and, more often than not, from his work and writings as well. Biographies of Freud have often been written by adherents of Freud’s psychoanalytic theories, and access to important letters and writings has been tightly controlled by his descendants and followers over many decades.

Frederick Crews, a professor emeritus of English in Berkeley, initially applied Freud’s psychoanalytic theories to literary criticism. Becoming disillusioned with its shaky foundations—and especially with the risks of psychoanalysis as a form of therapy—he then made it his mission to document who exactly Freud was and what he did.

Freud: The Making of an Illusion (2017) is the culmination of this project (some would say obsession) that started in the 1970s. At 746 pages (666 pages before the notes start), this is a hefty tome. It is organized chronologically, but this is not so much a biography but a re-assessment of Freud’s life from his student years to the early years of the psychoanalytic movement.

Past as prologue

Reduced to a few salient points, the book argues that Freud is guilty of harming his patients, of promoting quackery, of completely misrepresenting his case studies and persistently covering up the lack of any actual cures, of producing his wildest theories under the influence of cocaine (and then pretending they were the result of careful observations), of projecting his own sexual fantasies and frustrations upon his patients, of creating a self-serving cult that applied its beliefs in therapeutic practice without adhering to foundational ethical principles like primum non nocere, secundum cavere, tertium sanare (first, do no harm; second, be careful; third, heal).

Some of the most destructive aftershocks of Freudian thinking, Crews argues, could be felt as late as the 1980s, when “therapists” extracted false confessions of satanic ritual abuse from hundreds of children, producing a moral panic that tore apart families and even resulted in prison sentences which had to later be revoked. The underlying idea—that memories of traumatic events are repressed and can only be recovered by a skillful therapist—was one Freud himself believed in (and attempted to apply to patients) early in his career.

From 1912 to 1927, a Secret Committee with Freud at its center was tasked with defending Freud’s beliefs against dissenters and with protecting the central dogmas of psychoanalysis. Its members were gifted signet rings. (Credit: Israel Museum. Fair use.)

In Crews’ retelling, Freud starts his therapeutic career being absolutely convinced of one important truth: cocaine can cure anything. He used it over many years, he advocated for it, he prescribed it. For Freud, cocaine seemed to be the ticket to achieving wealth and fame, a miracle medicine whose countless potential applications had been overlooked.

Freud’s cocaine advocacy is an important example of his frequent total disregard for scientific principles and methods. Crews documents how Freud’s cocaine publications dramatically misrepresented his actual experience with the drug, much of which was the ultimately disastrous attempt to cure his friend Ernst von Fleischl-Marxow of morphine addiction using cocaine.

Blaming the victims

Freud would be an incredulous proponent of pseudoscientific and non-scientific ideas throughout his life. After his death, Freud’s followers carefully curated which letters and unpublished writings were permitted to be seen by researchers who were not part of the inner circle. This was very effective, and the public perception of Freud today is still shaped by the censorship actions taken by Freud’s true believers.

Freud’s correspondence with Wilhelm Fliess was held back into the 1980s due to the potential for embarrassing the master. Fliess, whose pseudoscientific idea of “biorhythms” still has some currency in the present, was also an advocate of nasogenital reflex theory, the idea that sexual problems are linked to the nose. I would say that you can’t make this stuff up, but evidently you can.

Freud blamed Emma Eckstein’s “hysteria” on masturbation. He recommended a quack surgery based on the belief that the nose is linked to the genitals. The botched operation almost killed Eckstein and left her disfigured. (Public domain, circa 1890.)

Freud considered Fliess “the Kepler of biology”. He embraced his friend’s most bizarre numerological speculations; nasogenital reflex theory had the additional benefit of connecting well with Freud’s own speculations about the alleged sexual origins of countless diseases. He referred a female patient, Emma Eckstein, whose “hysteria” he attributed to masturbation, to Fliess for a nasal surgery.

A near-fatal botched operation left Eckstein disfigured and suffering from frequent bleeding. In what was a common pattern, Freud blamed the victim: Eckstein’s bleeding was itself a “hysterical” symptom, a psychosomatic reflection of her inner wishes.

But when it comes to victim-blaming, that case does not hold a candle to Freud’s treatment of “Dora”, a young girl who was repeatedly sexually harassed by a friend of her family, starting at the age of 14. Her family did not take Dora’s word for it, however, and asked Freud to treat Dora’s “hysteria”. Freud happily complied with the parents’ wishes, and repeatedly attempted to pressure Dora into admitting that she secretly wanted the sexual relationship, after all.

Ice water

The reference to masturbation in the Eckstein case was not unusual but typical. As Crews puts it (p. 642f.):

As we have seen, Freud regarded masturbation—either its continuing practice or its abrupt and traumatic abandonment—as the precipitating agent of most neuroses. Through the first decade of the twentieth century, his relentless grilling of patients was chiefly focused on uncovering their histories in that regard. Albert Hirst recalled that when he entered treatment with Freud at age sixteen, the therapist immediately required him to sit “in the position in which I masturbated.” Other patients were enjoined not to masturbate for the duration of their care, lest a “current neurosis” be triggered.

But in most cases willpower alone, Freud believed, was insufficient to keep the hand from straying downward. In two 1910 letters, one to Ludwig Binswanger and the other to the Swiss psychiatrist Alphonse Maeder, he recommended that a masturbation-addicted male patient be subjected to treatment with a “psychrophore”—a catheterlike device for inserting ice water into the urethra. If Freud’s name were to invoke the image of a psychrophore instead of a couch or a cigar, we would be spared much needless discourse about his sponsorship of erotic freedom.

Far from being a trailblazer for future sexual revolutions, Freud held on to his reactionary views, even as scientists started to debunk the 19th century myths of “self-abuse”. Those ideas may seem funny today, but they were used to inflict untold psychological and physical harm in the form of more or less dangerous “cures”.

Powerful stories

It’s a common belief that Freud’s findings about what makes humans tick were real, but were primarily a reflection of a wealthy Viennese clientele who collected neuroses the way other people collect stamps or paintings. While some of Freud’s patients could be described that way, Crews makes it clear that the foundational ideas of psychoanalysis—such as the Oedipus complex—were not derived from real cases, but from Freud’s fondness for uninhibited speculation.

One of the big questions for me about Freud’s ideas has always been why people chose to give them any credence in the first place. Psychoanalysis in particular was never science, and Freud was neither as capable nor as meticulous as many other scientists of his era. Crews offers an answer which I find compelling: Freud was a brilliant storyteller.

Freud’s case stories were written like novels, and the psychoanalyst is the protagonist who cleverly deduces the truth from a few subtle clues. Never mind the fact that some of these stories were so utterly implausible that they are almost certainly complete fabrications—and others were, as we know from other evidence, heavily fictionalized or effectively retconned by Freud to bring them in line with his own frequently revised speculations.

Crews compares Freud to Arthur Conan Doyle, and Freud endowed himself with Holmes-like powers in many of his tales. These stories helped to cultivate the modern image of Sigmund Freud: wry, wise, witty and worldly.

Freud’s speculations about dreams, his invocations of mythological figures, his organizing of our lives into stages and drives, all of this speaks powerfully to our passion for story. Does it matter if much or all of it is bunk? It does to the extent that it hurts people, and to the extent that we want to call any of it science or medicine.

The verdict

Freud: The Making of an Illusion is still a necessary book, because psychoanalysis is still an influential idea, for the same reasons it became influential to begin with. Its defenders have simultaneously attempted to put distance between themselves and Freud, while also falsely crediting him for ideas that did not originate with him (see the Crews/Orbach dialogue in The Guardian, for example).

This is also a flawed book. Crews holds Freud in contempt, and in his effort to recast history, he often strays from facts to speculation. Did Freud have an abusive relationship with a sibling as a child? Did he fancy his own mother? Was he under the influence of cocaine when he wrote some essay or paper?

The book could be 150 pages shorter and more persuasive without the most speculative portions. This is not to say that Crews is sloppy; factual claims are generally very well-supported. Crews also always makes it clear when he’s theorizing. I had the impression that the 86-year-old author wanted to use what may be his last major work to tell us everything there is to know about Freud—including all of Crews’ own speculations and pet theories.

The tendency of the author to take these speculative detours works against the book in another important way: it gives Crews’ detractors plenty of ammunition to paint him as an obsessed curmudgeon with an axe to grind. I give the book 3.5 out of 5 stars mainly for this reason, rounded up to 4 because I’m quite certain that Freud: The Making of an Illusion takes us, at least, in the direction of a more realistic assessment of Sigmund Freud.

Back in 1977, Powers of Ten awed many children and adults alike with a presentation of our scientific understanding of the universe at different orders of magnitude, zooming out from a couple on a picnic blanket to the observable universe, then zooming back in, all the way down to the level of the hypothesized activity inside a single proton. (You can view the 9 minute film on YouTube.)

Astronomer Caleb Scharf’s book The Zoomable Universe updates this approach to our current understanding of the universe, aided by modernized visuals created by illustrator Ron Miller and a graphic design firm.

The book doesn’t start the journey on a picnic blanket, but at an order of magnitude of 10^27 meters—the “diameter of the cosmic horizon”—and ends at 10^-35 meters, the Plack length. At each order of magnitude, Scharf attempts to bring out astonishing facts, while narrating the journey in a conversational style.

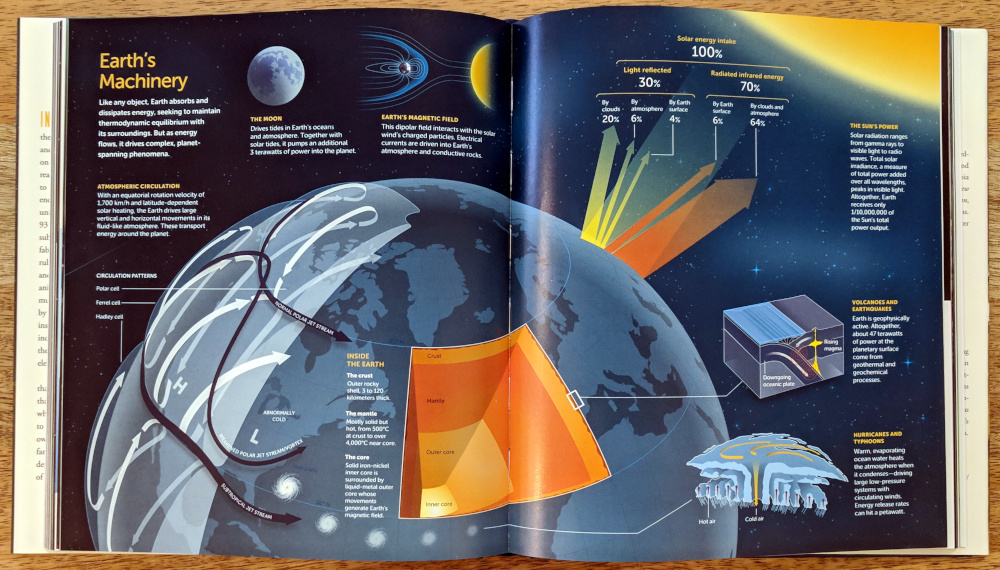

Full-page photographs, computer renderings and information graphics support each section of the book. Their quality and aesthetic style are somewhat inconsistent throughout the book, ranging from pretty basic computer renderings of imaginary planets to detailed and striking illustrations like the one below.

Illustration of the different forces at work on planet Earth. (Credit: Caleb Scharf / Ron Miller / SW Infographics. Fair use.)

Scharf’s text is informative, but it’s in the nature of a book like this to provide limited depth on any one topic. The objective here is to create a sense of wonder, and a high level understanding of how the universe operates at different scales. In that sense, the book functions as a kind of paper planetarium.

To Scharf’s credit, he does not shy away from attempting to explain the weird and wonderful world of the subatomic, and the book’s illustration of the famous double-slit experiment and the different interpretations of its results is especially lucid.

The book concludes with a notes section that is very much worth reading, giving additional background on the thinking that went into each section, and pointing to books, papers and websites for further exploration. I give the author high marks for this approach: notes don’t have to be boring!

While I found much of the material in The Zoomable Universe quite familiar, I still appreciated its thoughtful organization and the engaging presentation. I would recommend the book especially for younger readers, or those seeking to re-engage with astronomy, physics and biology (perhaps after a less than stellar experience learning about those subjects in school).

I’ll be honest with you: I rarely enjoy poetry; for the most part, it creates in me only the “feeling that I should be feeling something”. It’s a different story when poetry is set to song or to beautiful illustrations. Perhaps other readers create their own mental melodies when they read mere words; I require the assist.

With The Lost Words, Robert Macfarlane and Jackie Morris have created something even I can appreciate: a book that, through poetry and gorgeous art, invites a profound re-connection with nature.

The premise of the book is that words that refer to the natural world—words like “adder”, “conker”, “otter” and “wren”—are slowly disappearing from the language of children. And surely for many children growing up today, especially in urban environments, this is very true.

To restore these words—and the connection with nature they represent—to our lives, the book invites us to summon nature by reading out acrostic spells. Each poem is set alongside a beautiful full-page illustration showing the subject (e.g., a dandelion plant) in isolation; turn the page, and you’ll discover a two-page watercolor showing the subject again, now within nature. The spell for “bramble” begins as follows:

Bramble is on the march again,

Rolling and arching along the hedges

into parks on the city edges

All streets are suddenly thick with briar:

cars snarled fast, business over.

Moths have come in their millions,

drawn to the thorns. The air flutters.

…

This spell is then followed by an immersive illustration, making the most of the book’s large (27.7 cm x 37.6 cm) format:

Illustration of bramble, from The Lost Words. (Credit: Jackie Morris. Fair use.)

The Lost Words is not a science book; it does not provide explanation or context. In the beauty of its spells and illustrations, it builds something arguably even more important: the emotional foundation for our interest in nature. We will fail to conserve what we do not care about.

There is no doubt that Morris and Macfarlane have created a masterpiece, a timeless work that can be enjoyed by all ages. It is a book of few words, and it invites meditative reflection more than reading. I expect to pick it up again when it’s too cold and rainy outside to take a walk, but I still long to kindle my memory of the beauty of the natural world.

At the end of Adam Rutherford’s A Brief History of Everyone Who Ever Lived, we find an interview with the author. In it, he explains his writing process:

This may sound incredibly pretentious, but I write, and it only becomes clear to me what the point is about three quarters of the way through any particular section. (…) Fiction writers sometimes say that they don’t know what their characters are going to do next, and they are surprised when it happens. I feel like that sometimes in my writing.

It doesn’t sound pretentious to me, it’s just not a coherent way to organize history, especially not a project as ambitious as the one Rutherford is ostensibly attempting (the subtitle promises “The Human Story Retold Through Our Genes”).

What this book delivers is, instead, the following:

-

an overview of how our hard-won ability to sequence the DNA of the living and the long-dead has given us new insights into the history of early humans, including the inter-breeding of Homo sapiens with Neanderthals and of Neanderthals with Denisovans;

-

examples of anthropological and cross-disciplinary research projects utilizing DNA, with a somewhat parochial emphasis on British examples such as the People of the British Isles research project, and the discovery and DNA analysis of Richard III;

-

arguments on the limitations of DNA research, especially at the individual level, and about the pseudoscience of racial divisions;

-

a discussion of historical and ongoing evolution of humans;

-

a fair bit of griping about misrepresentations of science by media, corporations, and assorted charlatans, some sniping at creationists, and a bit more inside knowledge about Adam Rutherford himself than most readers are likely to require.

Rutherford is a geneticist and a presenter of science documentaries; he views himself as a storyteller, and if what you’re looking for is a casual, conversational and occasionally funny read about the (more or less) current state of genetics, as well as some solid debunking of racist nonsense, this is a fine book.

It is not, however, a well-organized history of humankind “retold through our genes”, nor is the writing so consistently good and entertaining to make up for this lack of organization. 3 out of 5 stars—there was enough new science for me to not give up on the book, but I would only recommend it with reservations.

Broken Age is a game that helped define the Kickstarter era by raising a record-breaking $3.45M in independent funding. Much of that support can be attributed to the love many now adult gamers still have for classic point-and-click adventure games that project instigator Tim Schafer worked on in the 1990s (Full Throttle, Day of the Tentacle, and others). Inevitably, a fair amount of Kickstarter drama followed which overshadows many reviews you’ll find online.

This review is written from the perspective of a point and click adventure fan who played the game well after its original release—I bought it for less than $5 during Gog’s winter sale. As of this writing, it’s back at $15, but you can wishlist the game to be alerted when the price comes down. It’s available for many platforms, including Linux and the Nintendo Switch.

Broken Age follows in the tradition of the genre, but unlike other entrants like Thimbleweed Park (review), it eschews pixel art in favor of a more modern look and feel. The world of Broken Age is beautifully drawn and animated, and none other than Elijah Wood (Lord of the Rings) lends his voice to one of the two lead characters, Shay.

The story is told from the perspective of Shay and Vella, who live very different lives. Shay lives on a spaceship whose computer coddles and infantilizes him. Meanwhile, Vella is a young girl apparently destined to be sacrificed to a horrific monster in a ceremony called the “Maiden’s Feast”, which is meant to prevent the monster from destroying the whole town.

During dialog sections, the game zooms in on the character who’s speaking. Key characters are voiced by well-known actors like Elijah Wood and Wil Wheaton. (Credit: DoubleFine. Fair use.)

As the player, you can switch between the two characters, and you will eventually learn how Shay’s and Vella’s lives are connected. The story is told with a lot of humor, and the full-screen art and professional voice acting create an immersive feel. The game respects the Fourth Wall and avoids gaming humor, instead inviting you to focus fully on the story.

The controls are simple—you can access your inventory at the bottom of the screen when needed, and click items or characters to interact with them—but that doesn’t mean that the game is too easy. The puzzles get progressively more difficult, and for the most part, they do make sense: pay attention to what characters are saying and what you’re seeing on the screen, and you can figure things out.

This changes towards the end of the game, when some very tricky puzzles depend on illogical knowledge-sharing between the two characters, and the characters’ goals become confused and confusing. In short, the ending of the game feels a bit rushed and underwhelming, which is a shame because the overall story is both clever and interesting.

Regardless, this is a game with a lot of heart that advances the genre rather than just wallowing in nostalgia. It’s great fun to explore its worlds, interact with the quirky characters, and unravel the central mysteries of the story. I reached for a walkthrough during the frustrating parts, and overall got more than 10 hours worth of fun out of my $5 investment.

4.5 out of 5 stars, rounded up because the good parts are really good, and the game represents a step forward for the point-and-click genre, especially in its art direction.

In the United States, the term “liberal” has become associated with the soup of center-left to center-right ideas promoted by the US Democratic Party, and it would be overly generous to ascribe to those ideas any coherent ideological foundation. Historically, liberalism (or “classical liberalism”) has a more specific meaning and is linked to the writings of figures like John Locke, Adam Smith, John Stuart Mill and Alexis de Tocqueville.

The importance of understanding what these individuals truly said and did has been elevated by what The Baffler called the “Classical Liberal Pivot”, the attempt by reactionaries ranging from outgoing GOP Speaker of the House Paul Ryan to InfoWars alumnus Paul Joseph Watson to frame their ideas through reference to a past most people only have a patchwork knowledge of.

Liberalism: A Counter-History by Domenico Losurdo (d. 2018) was published in 2011 and limits itself largely to the analysis of liberal thought up to the 20th century, with occasional reference to 20th century writers like Friedrich Hayek and Ludwig von Mises. As a counter-history, it intends to focus on the less well-known aspects of liberal ideology.

In particular, the book is concerned with how liberal ideology frequently defined civilization and humanity precisely in such a way as to support the goals of regional power elites at the time: to maintain and extend the system of slavery in the American South, to displace or exterminate Native Americans, to commit atrocities in French Algeria, Ireland or the British colonies, to coerce the poor into labor or military service, and so on.

To support this thesis, Losurdo primarily cites the writings of liberals themselves. Let’s work backwards: von Mises, a hero to free market libertarians, wrote in Liberalism, published in 1927:

It cannot be denied that Fascism and similar movements aimed at the establishment of dictatorships are full of the best intentions and that their intervention has for the moment saved European civilization. The merit that Fascism has thereby won for itself will live on eternally in history.

The Mises Institute complains bitterly that this quote is taken out of its context (in context, von Mises views Fascism as an “emergency makeshift”), but it’s hard to say how any celebration of Fascism’s eternally won merit can be rescued by context. This quote may be surprising, but it is mild stuff compared to the ideas of de Tocqueville, who celebrated the Opium War (a war waged by Britain to force China to buy opium!) with these words (emphasis mine):

I can only rejoice in the thought of the invasion of the Celestial Empire by a European army. So at last the mobility of Europe has come to grips with Chinese immobility! It is a great event, especially if one thinks that it is only the continuation, the last in a multitude of events of the same nature all of which are pushing the European race out of its home and are successively submitting all the other races to its empire or its influence. Something more vast, more extraordinary than the establishment of the Roman Empire is growing out of our times, without anyone noticing it; it is the enslavement of four parts of the world by the fifth. Therefore, let us not slander our century and ourselves too much; the men are small, but the events are great.

First Opium War display in the Shenzhen Museum. Alexis de Tocqueville celebrated the war as part of “the enslavement of four parts of the world by the fifth”. (Credit: Huangdan2060. Public domain.)

How can such ideas be reconciled with any concept of “liberty”? Losurdo unpacks this contradiction masterfully. Liberalism has consistently resolved the contradiction by defining the world into a “sacred” and a “profane” space. The “sacred” space is the one where liberty has to to be defended against despots; the “profane” space is that occupied by people who are inferior, less than human, “wild beasts”, rightly conquered, justly enslaved.

This profane space was reserved for women, the native populations of countries subjected to settler-colonialism, the Africans abducted in murderous journeys to serve as slaves in the colonies, people convicted of crimes (however immoral the basis of the conviction), the poor, the disabled, and so on, and so forth.

And it is with this distinction in mind we can understand that John Locke, “the father of liberalism”,

regarded slavery in the colonies as self-evident and indisputable, and personally contributed to the legal formalization of the institution in Carolina. He took a hand in drafting the constitutional provision according to which ‘every man of Carolina shall have absolute power and authority over his Negro slaves, of what opinion or religion soever.’ Locke was ‘the last major philosopher to seek a justification for absolute and perpetual slavery’. However, this did not prevent him from inveighing against the political ‘slavery’ that absolute monarchy sought to impose. [p. 3]

Perhaps nowhere was the contrast between rhetoric and reality more stark than in the American Revolution—a revolution in significant part undertaken to continue America’s genocidal expansion westward (which the British sought to limit), while perpetuating a horrific regime of hereditary chattel slavery. It is for these reasons that Losurdo refers to the new American nation as a “master-race democracy” and calls racial chattel slavery and liberalism a “twin birth”.

Losurdo quotes Theodore Roosevelt, who called “the inability of the motherland country to understand that the freemen who went forth to conquer a continent should be encouraged in that work” the “chief factor in producing the Revolution”; Roosevelt complained that Britain wanted to “[preserve] the mighty and beautiful valley of the Ohio as a hunting-ground for savages”. [p. 303]

Yet, it was the rhetoric of the American Revolution that inspired the French Revolution, which in turn inspired the Haitian Revolution by self-liberated slaves. Fearful that such an authentic struggle for liberty might lead to slave rebellions in the United States, Thomas Jefferson assured a French diplomat that “nothing would be easier than to furnish your army and fleet with everything, and to reduce Toussaint to starvation”. When the revolution ultimately succeeded, Jefferson imposed a crippling embargo that would last nearly 60 years.

Losurdo contrasts liberalism with the “radicalism” of the Haitian and French revolutions. It was precisely people in the liberal tradition who often argued and fought against broad liberation, whether it’s the abolition of slavery or the expansion of suffrage, limits on working hours and child labor, the recognition of trade unions, and so on. As new rights were won, the line between “sacred” and “profane” spaces shifted.

The author acknowledges that liberalism is, above all, an ideology adaptable to its time and place. Few “neoliberals” would argue for the re-introduction of child labor in wealthy countries, but many would describe horrific labor conditions in the rest of the world as a necessary evil (or even positive good) that’s part of economic development. Here we see a similar division of the world into “sacred” and “profane” spaces, but under greatly altered parameters.

The Verdict

Like many other academic writers, Losurdo is inclined to repetition, though to his credit, he often reinforces earlier arguments with new material. References to writers, historical figures and events are introduced rapidly, and I found myself looking them up on Wikipedia more than once to get my bearings.

A more serious criticism of the book is its uncritical use of derogatory terms like “redskins” throughout, and its relative silence on the role of women (and the patriarchal aspects of liberal ideology). Moreover, Losurdo makes no serious effort to draw the connections and parallels between “classical liberalism” and modern liberal or libertarian thought.

Nonetheless, if we want to recognize the patterns of history in the present day, we have to first know what these patterns are. Liberalism: A Counter-History is an important contribution to recognizing the rhetoric of liberation that may overshadow, or even enable, the oppression of those not included in its “sacred space”.

Among the 50 U.S. states, Mississippi has the lowest per-capita GDP and the highest poverty rate when not adjusted for cost-of-living. The state capital, Jackson, is about 80% Black or African-American; the city was named after slave-owner president Andrew Jackson who once placed an ad for the capture of a runaway slave promising “ten dollars extra, for every hundred lashes any person will give him, up to the amount of three hundred”.

Given the present and historical context, the election of Chokwe Lumumba as Jackson’s mayor, followed soon after his death in 2014 by that of his son Chokwe Antar Lumumba, upon a radical platform of political and economic liberation may defy stereotypes about the Deep South. But it is from the history of enslavement, terror and oppression that liberation movements emerged.

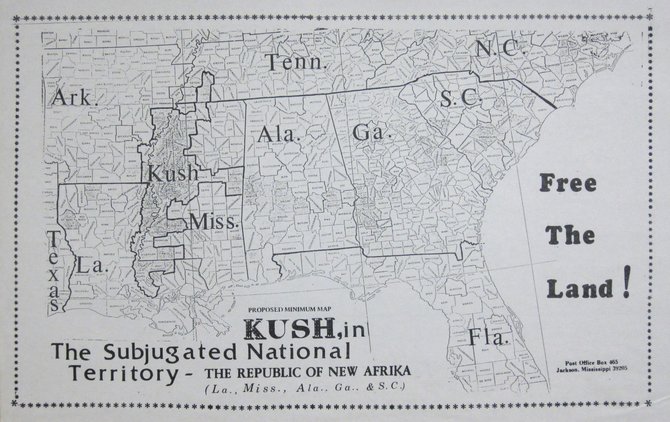

Cooperation Jackson is the movement that helped elect the Lumumbas, and which is seeking to build a bottom-up, co-operative economy not just in Jackson, but in the entire black-majority cross-state area referred to as the Kush (after an ancient African kingdom). Beyond its co-op elements, the movement seeks to mobilize the local community through assemblies to enact changes on the ground and to push for social and economic liberation.

In the early 1970s, the Provisional Government of the Republic of New Afrika planned for the Kush District to serve as power center for a new black-led nation in the South. (Credit: Republic of New Africa. Fair use.)

In practice, this vast ambition translates into much more tangible projects—urban farming and efforts to co-operatively run restaurants, grocery stores, and a fabrication center, for example.

Jackson Rising is a collection of essays dating to different points over the last few years, describing practical progress and laying out the movement’s vision for the future. The tension between what the movement seeks to achieve and what it can realistically accomplish with limited resources is palpable, and Cooperation Jackson’s recently published 2018 in Review describes the challenges of maintaining a coherent movement in light of these fundamental obstacles and ideological tensions within the movement.

The book can only be understood at offering snapshot insights into this ongoing experiment. The assortment of essays unfortunately suffers from a fair bit of repetition (the story of the elder Lumumba’s death in office, and the movement’s efforts to pick up from this this setback, is re-told multiple times, for example), and not all essays add much to the reader’s understanding.

One definite highlight of the book is the essay by Jessica Gordon Nembhard about the history of African American co-operative economic efforts, which were often a form of mutual aid in the face of terror, segregation and oppression. In her book Collective Courage, Nembhard offers a more detailed account of this history.

If you don’t end up picking up a copy of Jackson Rising but want to learn more about Cooperation Jackson, I recommend reading the online version of another article that’s included in the book: “The Socialist Experiment” by Katie Gilbert (Oxford American, September 5, 2017). It encapsulates the movement’s work up to the time it was published very well, without glossing over the enormous challenges of transforming a city’s economy from the bottom up.