Reviews by Eloquence

In Arrival of the Fittest (review), biologist Andreas Wagner made the compelling argument that life “finds its way” to solutions by way of neutral mutations. Through incremental changes, proteins can change shape gradually without losing their original function. As a population diversifies, natural selection can then identify those protein variants that have acquired entirely new, useful functions.

The book challenged a naive view of evolution, in which the vast majority of genetic mutations cause harm, and a small percentage of them confer an immediate survival benefit. The truth is that life needs to “play around” with neutral mutations to navigate the landscape of possible changes that may make a species more or less suited for survival.

In Life Finds a Way, Wagner applies this “landscape thinking” to all types of creative problem-solving. The first half of the book focuses on the concept of fitness landscapes, a limited but useful visual metaphor for how well-adapted specific genes (and the creatures they inhabit) are to their environment. The peaks in a three-dimensional landscape represent high levels of successful adaptation to the environment:

Visualization of a population of individuals evolving to become better suited for survival, i.e. “climbing a peak” in the fitness landscape. (Credit: Randy Olson and Bjørn Østman. License: CC-BY-SA.)

Natural selection marches steadily uphill. What prevents a population from being trapped on a small hill that represents an evolutionary dead end, an adaptation of limited usefulness that can’t be improved? Wagner breaks down how genetic drift (changes in frequency of specific gene variants), genetic recombination through sexual reproduction, and horizontal gene transfer in bacteria help individuals in a population slide or jump across the fitness landscape.

Wagner shows how potential energy landscapes in physics can similarly be used to map the possible configurations of molecules or crystals, and how gravity, thermodynamics and other physical forces push nonliving matter into stable (and often beautiful) configurations that represent valleys in the landscape.

Of mountains and molehills

In the second half of the book, Wagner applies landscape thinking to human creativity. He encourages us to visualize the map of creative solutions to a given problem (even if that “problem” is the composition of beautiful music) as a landscape with peaks and valleys. What does it take for a creative mind to climb mountains and avoid getting stuck on molehills of mediocrity?

The author enumerates many tools creative minds can use to traverse the landscape of ideas without getting stuck, including:

-

dreams

-

play

-

travel and exposure to other cultures

-

work with people from other disciplines

-

drugs.

As a positive model for cross-disciplinary work, Wagner cites the Santa Fe Institute, a renowned cross-disciplinary think tank where Wagner is an External Professor. (One way I hope they won’t be a model: even though the institute was only founded in 1984, its seven founders were all men, something Wagner does not remark upon.)

Into the badlands

Wagner harshly criticizes the obsession with standardized testing in the United States, and the rigid education approaches of South Korea and China. In his critique, he revisits familiar generalizations about “Western” and “Eastern” cultures, and seems to see “Eastern” cultures trapped in rigid uniformity, while situating the pinnacle of individual freedom in the United States.

Nations that want to nurture creative minds, Wagner argues, should reduce the negative consequences of failure—whether it’s for scientists applying for a research grant, or for entrepreneurs starting a business. Creative societies should be accessible to immigrants with diverse backgrounds, and recognize the benefits of diversity and individual freedom.

While Wagner pays lip service to the dangers of inequality, his analysis is stuck in a neoliberal frame of reference. Much more could be written about how an effective welfare state, a vibrant democracy, and alternatives to exploitative capitalism and intellectual monopoly rights (copyright, patents, etc.) are necessary to reap the benefits of human creativity for all people.

Instead, Wagner repeatedly cites Silicon Valley as an example for innovation, with the implicit assumption that the way to make a better world is to create more corporations like Facebook, Apple, and Tesla.

It’s worth remarking that Life Finds a Way was written before the COVID-19 crisis laid bare the utter incompetence of many “Western” governments, including the United States, in managing a pandemic. The landscape of ideas about COVID-19 is dotted with the creative edifices built by anti-vaxxers and ideologues, and landscape thinking alone seems like a very limited tool for getting humanity out of the badlands.

Thankfully, Wagner’s flurry of societal prescriptions is as brief as it is unimaginative. What we’re left with, then, is his argument to apply landscape thinking beyond physics and biology, providing an intellectual foundation for the value of letting our minds roam. That’s all it is—a foundation, one which I do hope other writers will build on.

Damn the Vek! Too stupid to communicate with, but smart enough to seek out human civilization wherever it is. In every timeline, the plague of giant insect monsters is close to wiping out what’s left of humanity. They breed underground and tunnel their way to the surface, only to bring death and devastation.

Insecticide won’t kill these bugs dead, but a squad of piloted battle mechs might. Or might not. Fortunately for the multiverse, humanity has learned how to travel between parallel universes, to attempt to rescue as many timelines as possible from the Vek.

Once more Into the Breach then, with another squad! Released in 2018, the second title by Subset Games after FTL cemented the tiny indie studio’s reputation for excellence. It takes plenty of inspiration from legendary turn-based strategy games (Advance Wars especially comes to mind), but still feels fresh and unique.

Much of this is due to the tightness of gameplay and mechanics. Assemble your team. Click. Pick a scenario. Click click. And: you’re in the fight. The map fits on one screen. You place your units. The enemy moves. The enemy starts to attack—and now it’s your turn.

A member of the Zenith Guard, a charge mech, finds its target. (Credit: Subset Games. Fair use.)

Depending on your squad and each mech’s buildout, you can destroy units, push and pull them, create hazards, create shields, and more. The array of skills turns every round into a small puzzle. How will you prevent the enemy from damaging your units, or killing civilians in a building, or destroying strategic targets?

Miscalculate, and the Vek might end up taking down the energy grid—game over. It’s permadeath, sort of: you can take one of your pilots to the next timeline. Too bad for this one.

An Honest Roguelike

From a limited number of ingredients, the game cooks up a fresh set of scenarios for you on each run. Some maps are especially difficult to beat without taking some hits to buildings; any damage you take to the energy grid carries over to the next map. You have to make some strategic choices between battles—which battles to fight, which upgrades to install—but most of the game is tactics, tactics, tactics.

The difficulty level is not quite as punishing as that of FTL or other roguelikes that celebrate starting over as part of the fun. At normal difficulty, you may notch your first game victory after a few runs, perhaps even on the first try. The Vek are as stupid as they are relentless. But the game will produce enough brain twisters to keep you coming back.

When you manage to shove a nasty Vek into the sea, or cause a chain reaction of monsters killing each other, it’s quite the payoff. If that isn’t enough, the game rewards you with unlockable squads, experience points, upgrades, and ambient dialogue that never gets in the way.

Mission briefings are terse, but there’s a large enough variety of objectives to keep things interesting. (Credit: Subset Games. Fair use.)

The Verdict

While it’s a very different game than FTL, it’s clearly built with the same design philosophy. The pixel art is more beautiful than FTL’s, but never extravagant; the UI provides help when it needs to and otherwise gets out of the way; moving your units feels as straightforward as moving the pieces on a chessboard.

In spite of the absurd premise and cartoonish physics (units can be encased in ice and unfrozen without damage), the game’s tone is mostly somber; even victory is just a brief reprieve in an endless war played out across universes. The fun is in solving the puzzles the random number generator throws at you and kicking some serious Vek butt. If that kind of turn-based strategy sounds like your cup of tea, you can’t go wrong heading Into the Breach.

Cursed Sight is a visual novel developed by Marcus “InvertMouse” Lam, an Australia-based indie developer. We meet the protagonist, Gai, at the age of 10 when he is sold by his parents to work as a servant for the king of East Taria, a fictional Asian kingdom. Gai becomes responsible for helping to protect the kingdom’s “treasure”—a young girl named Miyon born with dangerous abilities that King Lok is exploiting.

As the story progresses, Gai develops a friendship with Miyon and her caretaker, a young woman named Sasa. As Gai and Miyon grow older, they consider what kind of life may be possible beyond the captivity of the temple. Their decisions could cost them their lives, and they will certainly shape the future of the kingdom.

This is a mostly kinetic visual novel, meaning that you read it by clicking through it. There are 4 different endings, which you access through a couple of branch-points in the story where you do get to make choices.

Miyon is a young girl who is held captive to exploit the mysterious power of her cursed sight. Beautiful screens like this one are used as segways between different chapters of the story. (Credit: InvertMouse. Fair use.)

The art is lovely, and the music, while repetitive, fits the setting. The story is not voiced. The writing is decidedly mixed. Gai never quite acts his age (his 10-year-old version is too adult, his adult version is too childish); some paragraphs really needed an editor; anachronistic references and expressions distract from the setting. The most cringeworthy example is this one:

Miyon had opened up so much that I worried the other servants, or even guards, might become interested in her. I would fight them all in a cage at the same time if they dared touch her. Well, maybe after I attached a chainsaw to my left arm.

(Yes, that’s a reference to a chainsaw in a game that is meant to be set in the distant past.)

The game is at its strongest when it conveys emotions and builds its characters. I certainly became invested enough to finish the story and to get to all four endings, and the story moved me to tears a couple of times. While the game is only of average quality overall, there’s the kernel of something lovely here, and I look forward to playing more of InvertMouse’s games in the future.

Bad writing grasps at your attention like a man grasping at straws; great writing seizes your attention and doesn’t let go. Eliza is a computer game, and its writing is firmly in the latter category; it has a story to tell, and the moment it begins telling it, you want to know how it ends.

This is a visual novel, a genre in which you typically click your way through an illustrated story and make a few choices along the way. You play as a young woman named Evelyn who, after a period of depression and burnout, starts a job working for an AI-based counseling service called Eliza (in homage to the 1966 chatbot of the same name).

Evelyn works as a proxy, a human face for the AI. Proxies are required to faithfully read their lines to customers—”don’t deviate from the script!” Some of the people Evelyn meets as a proxy are looking for treatment, some just want a person (or a machine, as the case may be) to talk to. The game uses this conceit to explore deeper questions about the role of technology in a capitalist society.

As an undercurrent, Eliza explores the culture of the tech industry. There’s the startup founder with the grand vision of “ending human suffering”, who seems to harass every female staff member he hires. There’s the idealistic young engineering manager who is starting to raise questions about the privacy practices of his employer. And there’s Evelyn’s friend Nora, a former programmer who is now freelancing and making electronic music.

Evelyn (right) meets her colleague Rae for a cookie-baking session. (Credit: Zachtronics. Fair use.)

The game offers small choices throughout, but their effect tends to be very limited. In fact, when you act as the AI’s proxy during counseling sessions, the game deliberately takes away your choice to say anything other than the dialogue generated by the AI, occasionally forcing you to say “I’m sorry, I don’t understand the question” as if you yourself were an algorithmically constrained chatbot. It’s player frustration in service of the story.

At the end of the game, Evelyn must make a defining choice, which leads to one of several endings. The game does not punish or reward you for your choice with a “good” or “bad” ending; instead it concludes the story in a manner that suits the character you’ve chosen to become.

Eliza took me about 6 hours to complete, and that includes exploring the different endings. The dialogue is fully voiced by a cast of experienced voice actors. Backgrounds and character sprites are visually pleasing, but the graphics are completely static—facial expressions or poses don’t change, even when the dialogue suggests that they should.

The Verdict

Eliza falls a bit short on the “visual” side of being a visual novel due to its use of static images; as a game, some players will find its linearity and long sequences without significant player choices overly limiting. But as a story about the role of AI in society, it is gripping and timely. If the theme interests you, I recommend the game without reservations.

Every once in a while, I’m drawn to the tower defense genre, where you must dispatch with waves of enemies by building stationary defenses that fire on anything that moves in their proximity. It’s real-time-strategy reduced to the barest explodey foundations, with all action often taking place on a single screen. Unsurprisingly, the genre thrives on tablets and other mobile devices.

Cursed Treasure 2 differs from the stock formula mainly in two ways: You play as an evil overlord, and your enemies are trying to steal your stuff (gems in this case). If they steal all of it, you lose the level. That gives the player a more active role in the proceedings—you have to always keep one eye on those gemstones to prevent your enemies from absconding with them. If you have enough mana, you can summon a meteor to smush your opponents, or you can strike terror into their hearts to deter them.

After winning a level, you can play it in “night mode”, which restricts your placement options for towers to add a bit of difficulty; between levels, you can spend experience on assorted power-ups. All in all, the game offers enough variety to keep things interesting for a while—I put about a dozen hours into it.

Fighting one of the bosses in the last level. (Credit: Armor Games Studios / IriySoft. Fair use.)

The downsides:

-

There’s no story to speak of, and some of the English text on the screen would have benefited from copyediting by a native-level English speaker.

-

The game crashed once on me, and it forget its savegames a couple of times (restarting the game again made them re-appear).

-

By the time you’re really comfortable with all the mechanics, the game is over; unless you’re a dedicated completionist, night mode just doesn’t offer enough to pull you back in.

Still, you can often pick this up for a dollar, and it’s a solid game with a decent Linux port. Recommended if you’re like me and occasionally just want to fill your screen with things that go boom.

Life is Strange (reviews) established the team at Dontnod Entertainment as talented storytellers and worldbuilders. The game was a joy to explore and offered meaningful player choices that elevated it above the status of mere “walking simulator”. The story it told had a definitive ending; what, then, could a sequel have to offer?

While Life is Strange 2 occupies the same universe and is structured in a similar episodic format, it tells a completely new story, setting the series up as an anthology—think Fargo or True Detective, not Stranger Things.

The second season is about a 16-year-old kid named Sean Diaz and his little brother Daniel. After a traumatic incident, Sean and Daniel find themselves running away from home and wanted by the police.

As the player, you control Sean’s actions and define the kind of relationship you will have with your brother, and with the world you both inhabit. Will you and Daniel steal food to survive, or beg for scraps? Will you attack those who wrong you, or forgive them? Will you trust in the kindness of family and strangers, or face the odds on your own?

The story takes place in America under Donald Trump, but the writers make a point to include moments of love and tenderness alongside the darkness of racism and prejudice that Trump represents.

A story told by Sean to his little brother sums up the events so far at the beginning of each episode. In the story, Sean and Daniel are “wolf brothers”. (Credit: Dontnod Entertainment. Fair use.)

Warning: The text below contains spoilers.

Like the first season, Life is Strange 2 has a supernatural element. Early in the game, it becomes clear that Daniel possesses significant telekinetic powers. As the player, you coach Daniel on when and whether to use his powers, but you do not control them directly, and your choices are not reversible.

Life is Strange 2 improves on the first game’s graphics, which is especially noticeable during the sequences where you explore natural environments like the forests of Washington and Oregon, or a canyon in Arizona. Like the first season, the game is fully voice-acted. Unfortunately, I felt that Gonzalo Martin (Sean Diaz) often overacted his part, which is significant because he’s the main voice you’ll be hearing throughout the game.

Besides making choices and occasionally solving small inventory-based puzzles, you also get to collect souvenirs on the road, which you can inspect in your backpack later. Moreover, Sean Diaz is an aspiring artist, and at various moments you can sit down and draw in your sketchbook. You don’t directly control the pen, but you can choose between different ways Sean sees the world: Is a room you’re trapped in a prison, or can you already see a stairway to freedom?

In the last episode, you and Daniel briefly explore a canyon in Arizona, showcasing the game’s significantly improved graphics. (Credit: Dontnod Entertainment. Fair use.)

The first Life is Strange ultimately presented the player with a choice between two very different endings. Life is Strange 2 builds towards a similar choice, but the endings depend not just on that one decision, but on the cumulative effect of your actions so far. For my playthrough, this worked really well. I felt that the ending corresponded beautifully to how I had chosen to act as Sean. That’s a rare feat for a game.

I enjoyed the game, and recommend it. Like the first title, it depends heavily on the chemistry between two characters—in this case, Sean and Daniel. I did not find those characters quite as compelling as Max and Chloe in the first game, partially due to the voice acting, and partially because playing out an at times strained relationship between two siblings is just more emotionally exhausting.

I would rate the game 4.5 stars, rounded up because the team at Dontnod clearly poured their hearts and souls into this game. If you’re looking for mindless escapism completely detached from reality, this is not the game to pick, but if you invest yourself in its story and characters, the game rewards you with a narrative arc that truly feels like you’ve made it your own.

Small biological miracles occur all around us. Birds, dragonflies, moths, or butterflies you observe during a hiking trip may be in the middle of migrations that require them to navigate distances of hundreds or even thousands of kilometers. A honeybee feeding on the nectar of a sunflower in your backyard may later share its distance and direction with the hive by way of a complicated waggle dance.

In an age where many of us rely on computers and satellites to tell us where to go when we travel off our beaten paths, these feats of animal navigation are all the more impressive. To find their way, animals rely on the sun, the moon, and the stars; on sound, sight and smell; even on superpowers we lack, like the detection of subtle variations in the intensity, inclination, and declination of the Earth’s geomagnetic field.

In Supernavigators, David Barrie reveals the navigational tools and methods utilized by animals ranging from insects to humpback whales. He compares them with navigation strategies employed by humans, from Polynesian voyagers to the Long Range Desert Group, a British reconnaissance and raiding unit in World War II.

Barrie is no stranger to the subject of navigation. His previous book, Sextant, focused on the use of the titular instrument for celestial navigation, and the author is an experienced sailor. Like many popular science books, Supernavigators is not just about what we know, but also how we know it. Barrie visited and interviewed many scientists, and he even accompanied a scientific expedition studying the long-distance seasonal migrations of bogong moths.

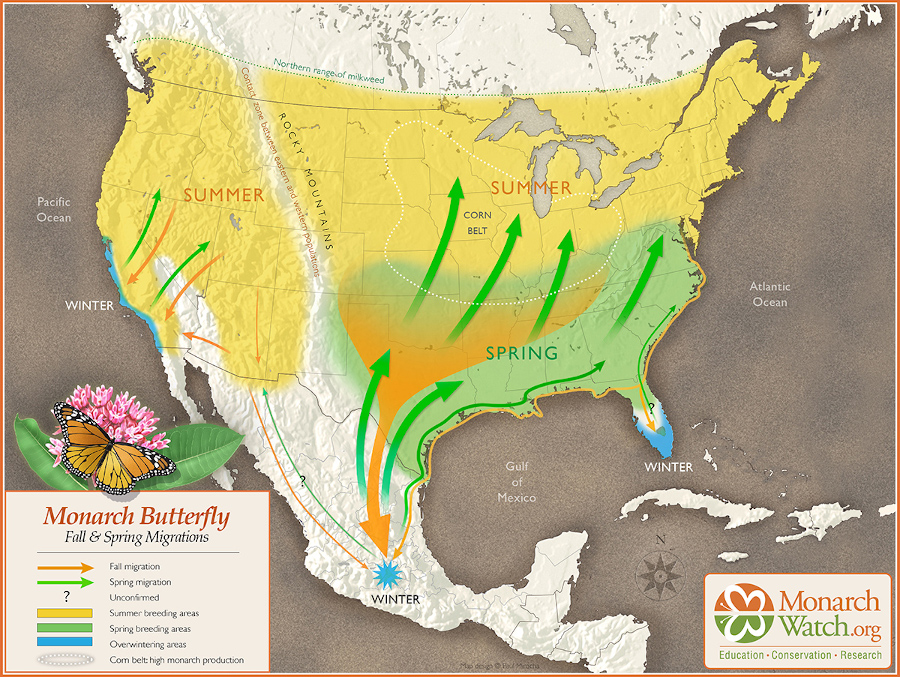

Monarch butterflies travel up to thousands of kilometers as part of their seasonal migrations. To navigate over these large distances, they are aided by a time-compensated sun compass sense. (Credit: Paul Mirocha / MonarchWatch.org. Fair use.)

Journey Into Minds

Knowing how animals find their way across vast distances may seem like a problem of elimination. Given an animal’s ability to see, smell, listen, feel, or sense, which sensory inputs actually matter for a long-distance journey? To test competing hypotheses, animals are deprived of vision or smell, displaced, confused with false sensory inputs, placed in funnels, tagged, tracked, and sometimes even mutilated.

One pattern that emerges from the many experiments described by Barrie is that animal minds—even those of insects—are complex, and animals often make the best use of all navigational information available to them. A subtle change in geomagnetic inclination may be no less important than the smell of coastal vegetation, the direction of the wind, or the movement of stars around the Northern Star.

Towards the end of the book, Barrie briefly criticizes the long history of anthropocentrism in biology, which essentially reduced animals to stimulus-response robots categorically distinct from humans. He reminds us that we are animals, and appeals to us to not let our own navigational skills atrophy. Becoming literate in the “language of the Earth” is a way for us to remain connected to our planet, and to treasure the richness of life on it.

The Verdict

Supernavigators made me say “wow” out loud a few times as I read it; this is testament both to the fascinating subject matter, and Barrie’s ability to convey it. I appreciated the simple sketches that illustrate some navigational concepts, and the brief anecdotes at the end of each chapter that are meant to show how little we still know about animal navigation. While the book would have benefited from some more synthesis and a bit less repetition, if you are interested in the subject, I don’t think you’ll be disappointed. 4.5 stars, rounded up.

You are Maxine “Max” Caulfield. You are 18 years old. You live in Arcadia Bay, a seaside town in the US state of Oregon. You’re a student at a private high school with an arts and science focus. No matter whether you’re at school, at home, or at play, you and your Polaroid camera as inseparable. Perhaps one day your pictures will catch the eye of Mark Jefferson, a famous photographer who teaches at your school?

This is the seemingly ordinary setting of Life is Strange, a narrative adventure game developed by Dontnod Entertainment and published episodically through 2015. The game is played in a third-person 3D view, rendered in an artistic style situated firmly between painterly and photorealistic. While not up to today’s technical standards, the game world is still beautiful and immersive.

Your experience as Max starts with a nightmarish vision of destruction. But it was only a daydream; you’re in school, and Mr. Jefferson is asking you about the technical process that gave rise to the first photographic self-portraits. It’s only after a dramatic encounter with a childhood friend, Chloe Price, that things really get strange. And what is the story behind the disappearance of Chloe’s friend, Rachel Amber?

Max in Chloe’s room. The game lets you explore its rich environments at your own pace, taking in every detail if you want to. (Credit: Dontnod Entertainment. Fair use.)

In terms of gameplay, Life is Strange has much in common with classic point-and-click adventure games: You spend a lot of your time exploring, talking to other characters, and solving small puzzles. There’s no unlimited inventory—occasionally a puzzle may involve finding an object and carrying it from one location to another. There is one additional game mechanic (spoilers ahead):

Warning: The text below contains spoilers.

You discover early in the game that you have a limited ability to reverse the flow of time. This often allows you to try different decision paths and compare outcomes. It makes for a world that feels real and responsive (decisions have consequences) without painting you into a corner.

The game is fully voiced, and it’s a joy to poke at objects in the environment and listen to Max reflect on what she sees in the world around her. If you sit down on a bench, you may be rewarded with some additional wide angle camera views and narration. If you prefer to rush through the story, you can do that, too.

Life is Strange is not a perfect game (some scenes overstay their welcome, for example), but I still consider it a masterpiece in interactive storytelling. It’s a joy to explore Arcadia Bay, thanks to the excellent art direction and attention to detail. The wonderful chemistry between Max and Chloe invests the player in both characters.

The first episode of the game is available for free, and you can often pick the whole game up for under $5. Thanks to Feral Interactive, there is an excellent Linux port, as well. If your computer is not a potato and you enjoy narrative adventure games, Life is Strange is one title you won’t want to miss.

FTL: Faster Than Light is now more than 8 years old, but it looked outdated when it was released. Start up the game, and you’re greeted by a low-resolution “LOADING” font, followed by a static title screen featuring a fleet of spaceships parked ominously in front of a planet. The first hint that this game has hidden depths is its memorable title theme, wonderfully evocative of the quietude of space.

The story is told in the simplest terms: You command a lone federation starship that is on the run from the malignant Rebellion (think US Civil War rebels, not Star Wars rebels). Your faster-than-light drive lets you make jumps from one galactic beacon to the next, through several sectors of space that are newly generated on each playthrough. You’re trying to reach the last stronghold of the federation, in order to defeat the Rebel Flagship that’s threatening to destroy it.

Almost every galactic beacon holds a story, or part of one: you run into slavers, traders, pirates, and rebels; you rescue raving madmen and space colonists; you find weaponry and treasure. You often get to make choices, with randomized outcomes. (Stay clear of the Giant Alien Spiders until you know what you’re doing; they are no joke.) At first these scenarios may seem repetitive, but your options will increase depending on your ship and crew.

We’re about to get blown to bits by the rebel flagship. (Credit: Subset Games. Fair use.)

Space War!

Many encounters turn into ship-to-ship battles, and that’s where the game really shows its genius. Combat takes place in a real-time-with-pause system that allows you to plan your every move, or to shoot from the proverbial hip. Planning is often advisable, as you may find yourself at a disadvantage even in early encounters.

Each of your ship systems matters, and so does each of theirs. Do they have teleporters, which they’ll use to board your ship and fight your crew? Are you able to hack into their systems, maybe sabotage their shields or their cloaking device? Do they have a flak weapon that will shower your ship with debris? Can you use that asteroid field in your favor?

Some battles are unwinnable (given enough time, you can try to jump away), others will only seem that way to the new player. But it’s almost always fun to figure out what you can do with the cards you’ve been dealt, and to master the ship you’ve chosen to command. There are 10 ships to unlock, and different layouts for each, demanding very different styles of play.

There’s more that could be said about the game’s systems, from ship upgrades to crew recruitment and experience, from drone warfare to oxygen management. In its totality, the game really makes you feel like you’re commanding the crew of a spaceship, and your imagination fills in what the simple graphics cannot.

Death Without Friction

From this description and from screenshots, FTL may appear like a dauntingly complicated game, but this is where the game’s second core strength lies: an absolutely delightful user experience. Move your mouse across the screen, and you’ll get helpful explanations; keyboard and mouse shortcuts are readily available for everything you need often.

How do you increase or decrease the power for the shield systems? In many games, you’d have to click a “+” and “-” button, or drag a slider; in FTL, you left-click to increase, right-click to decrease, or use a keyboard shortcut. And so it is with the rest of the UI: easy to learn, quick to repeat.

I’m a big fan of NetHack (one of the early games that gave us the term “roguelike”), and FTL is the closest equivalent with a space opera setting that I have encountered. The low-friction user experience is a huge part of what makes it all work—it allows you to focus on story and strategy, instead of mechanics that get increasingly annoying through repetition.

Every roguelike tends to claim that “losing is part of the fun”, and in the case of FTL, it’s usually true. Except for when you’re getting hammered by pirates while solar flares are lighting every part of your ship on fire, for the 15th time…

The Verdict

5 stars, no contest. I honestly can’t say enough good things about FTL—it’s a masterpiece of indie game development that has made developer Subset Games an industry legend (their second game, Into the Breach, is very different but no less luminous). The native Linux version works beautifully, and the game is available in 10 languages. There are also amazing-looking mods, but I have not tried them yet.

Even at $10 on GOG, the game offers excellent value (as of this writing, I’ve put some 100 hours of play into it) but it regularly goes on sale for far less. Be aware that this isn’t a fair game—as with most roguelikes, the RNG will put you in impossible situations—and if that tends to prevent you from having fun, you may want to avoid it. For everyone else, FTL continues to be a beacon calling us to assist the federation, just one more time.

What’s in a game? Is it that you have to click the right button at the exact right moment? Or that it transports you to another world? Mutazione is firmly in the latter category—a narrative adventure with no action sequences and barely a puzzle in sight, but with a world that comes alive with ambience and the characters that inhabit it.

The world of Mutazione is a joy to explore, even if the overall experience is very linear. (Credit: Die Gute Fabrik. Fair use.)

Mutazione is also the name of the island where most of the game takes place. It’s a place implausibly forgotten by the rest of civilization; an island whose flaura and fauna (including its human inhabitants) have been transformed by a meteor impact many years ago. You play as Kai, a teenage girl who visits her sick grandfather on the island, and in the process becomes immersed in its past, present, and future.

Much of the gameplay consists of Kai walking from place to place (or person to person), occasionally performing simple fetch quests to advance the plot. Dialog (which isn’t voiced) gives you limited choices, such as the option to crack a joke in response to someone else’s remark, or to remain silent.

Gardening With Feeling

Each game day is broken into segments, and you decide when to advance from morning to noon, from afternoon to evening. As the game time advances, so do the game’s little subplots, including a fair bit of soap opera about love relationships that are burgeoning or that seem to be falling apart.

It soon becomes clear, with her grandfather’s help, that Kai has a gift for gardening in Mutazione’s unusual ecology, where music, emotion, and plant growth seem to be inextricably connected. Throughout the game, you will collect seeds and cultivate gardens situated in different microclimates. If you fear or hope that there’s a challenging mini-sim hidden inside the game, it’s not so: the gardening parts of the game are meditative and creative, not difficult.

A “garden mode” is unlocked after you complete the story, which lets you experiment to your heart’s content. Or so I’m told—in the Linux version, the mode never appeared for me after I finished the game.

The Verdict

Mutazione is undeniably gorgeous. The art direction is simply stellar, from beautifully drawn abandoned buildings, to chickens scattering as you approach them, to spear-wielding, sentient dots refusing to let you enter their habitat. The soundtrack is great, too, and when the island band performs a song in the local bar, you can imagine that you’re right there with the mutants.

The plot is largely coherent, but much of the game is about making emotional connections. The characters of Mutazione have their own fears and ambitions; they don’t exist to help the player reach some goal, but they do make Kai feel welcome in this world that is as new to her as it is to us.

I would give the game 4.5 stars, rounded up. If you enjoyed Oxfenfree but found its spooky story a little bit stressful, you’re likely to love Mutazione. The only thing I missed is a sense that I had control over where the story was headed, or at least a final game-defining choice. Narrative designer and writer Hannah Nicklin has described the game as having “multiple middles” instead of multiple endings, and that’s true—there’s enough to uncover, at least, to justify a second playthrough. In any event, the first playthrough is well worth the price of admission.