Reviews by Eloquence

Some games are pure perfection. Tetris on the original Game Boy comes to mind. Super Hexagon by Terry Cavanagh (a $3 indie title w/ cult status) is another such game. It’s almost a trainer for achieving flow state.

You pivot a triangle between rapidly approaching walls that will immediately crush you upon collision. To survive, you must learn repeating patterns and keep your reaction speed high.

Chances are you’ll crash and burn after a few seconds. And again. And again. The game design is optimized to keep you playing: restarts are instantaneous, and the (excellent) chiptune music shifts a little bit on each restart to keep things interesting. A few seconds may turn into hours before you notice.

This screen, which you will see a lot, shows your current and best score for the level you’re playing. (Credit: Terry Cavanagh. Fair use.)

You are almost certainly going to beat the game’s first couple of levels if you keep trying. When you do, it feels incredibly rewarding. At the same time, while staring at triangles and hexagons for an hour, it can be hard to shake the feeling that you’re in some sci-fi story in which your brain has been hijacked to serve a terrible purpose.

Even if you normally don’t like twitchy games, Super Hexagon may surprise you with its elegant simplicity. Unless you have an aversion to flashing lights and colors, I highly recommend giving it a spin. I come back to it at least once a year.

Karawan is a small, free indie game that came out of this year’s Ludum Dare jam. Turn by turn, you guide a growing caravan through a world that is rapidly falling apart, to a portal that will take you to safety.

To make it, you have to carefully plot your path and pay attention to the resources you can gather along the way. If you don’t, you are likely to run out of food, or you may find yourself on a tile that’s about to disintegrate.

As you traverse the map, you can visit various villages, where you can recruit caravan members with different skills: farmers who will harvest berries, woodcutters who will chop down forests, and miners who will collect gemstones.

The first map, Gaia, is fairly straightforward, but you will likely still take a few tries before you make it to safety. (Credit: bippinbits. Fair use.)

You can also choose to raid villages for resources instead. Some of them are protected by a wizard (called a magus), whom you can recruit. The magus is quite powerful, and can even alter the terrain around you.

The game’s stylish pixel art, sparse but evocative descriptions, and the slow, slightly eerie music all draw you in. Don’t let the game’s chill tone fool you: seeing the world disappear behind you will quickly create a sense of urgency for your journey. Karawan may hook you for at least 30-60 minutes, longer if you want to beat all maps. I recommend downloading the slightly improved PostJam version.

The game was made with the open source Godot Engine, and is available for Windows and Linux.

Gabriel Knight is a lout. He is also the owner of a bookstore in New Orleans’ famous French Quarter, and a struggling novelist researching a spree of apparently voodoo-inspired killings that have gripped the city. Through his friend Frank Mosely, a police detective investigating the killings, he is able to learn more about the case than what’s reported in the papers.

As he travels the city and speaks to people who may be able to shed light on the case, his shop assistant, Grace Nakimura, minds the store, takes messages for Gabriel, and undertakes research on his behalf. Gabriel is a womanizer, and Grace knows him well enough to keep some distance between them.

What could be the setup for a movie or a TV show is in fact the plot of Gabriel Knight: Sins of the Fathers, a 1993 video game designed by Jane Jensen and published by Sierra. The game is fully voice-acted by a cast that includes Tim Curry (Gabriel Knight), Mark Hamill (Frank Mosely), Leah Remini (Grace Nakimura), and Michael Dorn (Dr. John).

You control Gabriel’s actions in typical point and click fashion: click on hotspots on the screen and interact with them using various actions (look, operate, talk to, etc.). As is typical for the genre, you can carry as much stuff with you as you want, and you’ll want to pick up anything you can.

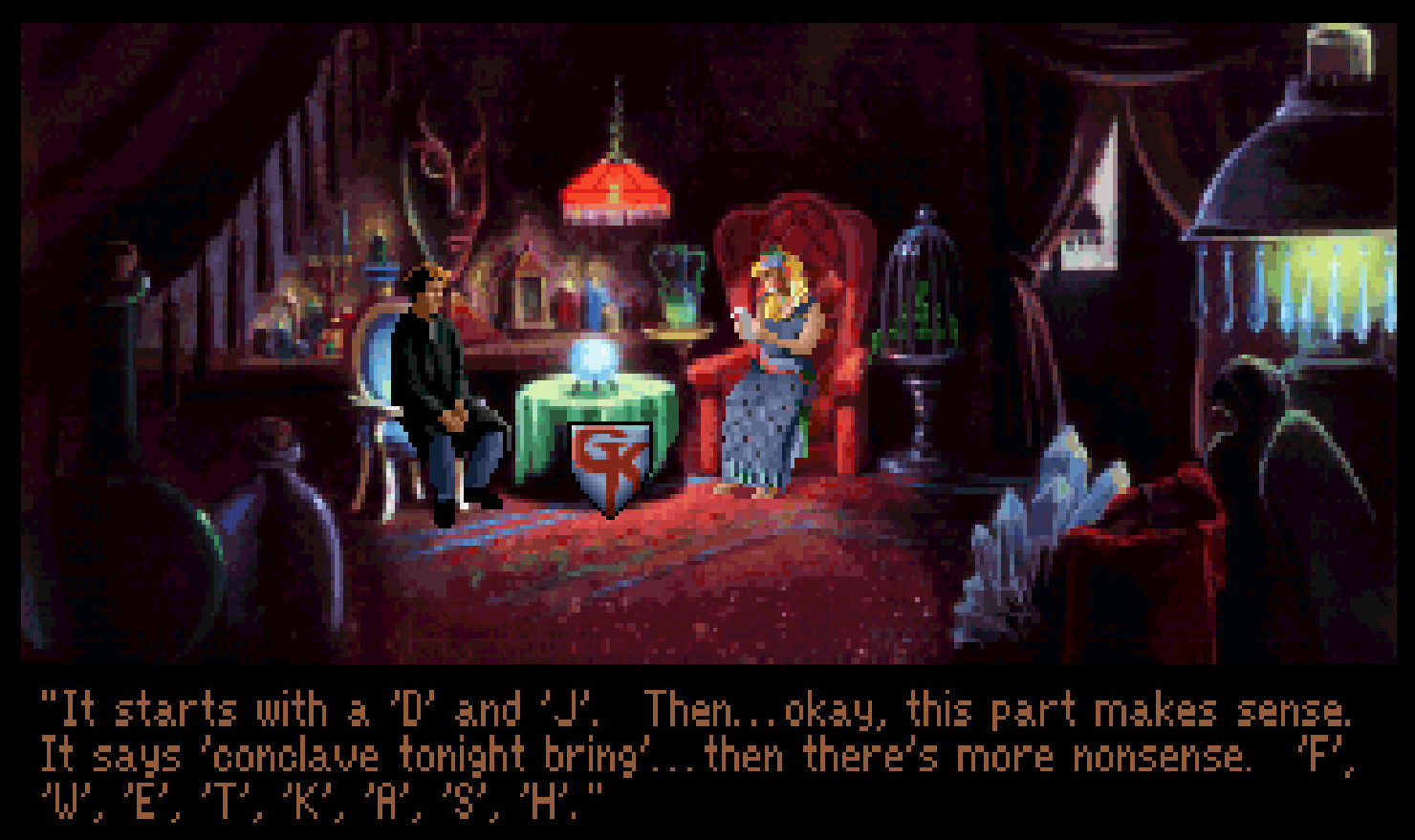

Cut scenes like this one may reveal important clues to the game’s puzzles. (Credit: Sierra On-Line. Fair use.)

Driven by story and dialogue

There are some important ways in which Gabriel Knight sets itself apart from many other games of its era:

-

The game has a narrator, voiced by Virginia Capers with a thick accent, who often inserts her own commentary about Gabriel’s (attempted) actions, and seems to take some delight in his misfortunes.

While other Sierra games have featured narrators, Capers gives the game a unique personality when, for example, she bursts into laughter as you examine an item in Gabriel’s inventory that relates to a near-death experience. -

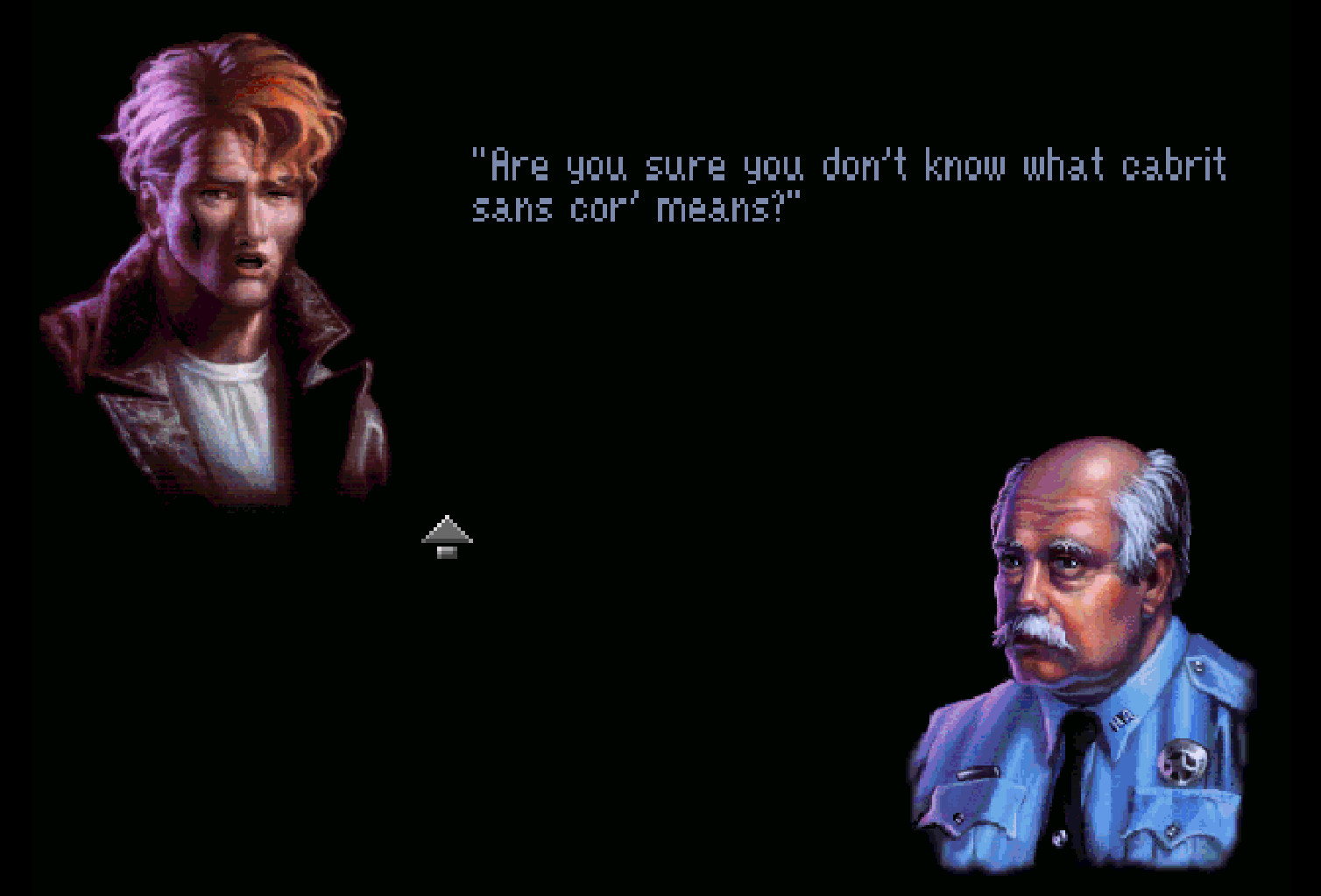

Dialogue is a central part of the gameplay. There are separate “talk” and “ask” actions. When you talk to a character, Gabriel will usually cycle through a few casual remarks; when you ask them questions, the game switches to a focused dialogue interface in which you can choose subjects to discuss.

Although the dialogue tree grows to a somewhat ridiculous length (you can literally ask anyone you come across what they know about the voodoo murders, or whether they know the meaning of “cabrit sans cor”), the dialogue system is a nice departure from the usually very limiting conversational options of adventure games. -

The plot advances over the course of 10 days, and the locations and possible interactions change over time. As you visit the police station on different days, for example, you will learn about how the case has progressed since you last spoke to detective Mosely.

The game’s sense of time is entirely tied to specific actions of your character. It’s only when you have solved certain puzzles, or asked certain questions, that you can move on to the next day. This can be frustrating, as only the game knows what specific thing you have to do to unblock the flow of time.

Gabriel Knight was one of the first adventure games to utilize higher resolution SVGA graphics, but it did so only in a limited fashion, such as in the dialogue interface. (Credit: Sierra On-Line. Fair use.)

A product of its time

It is a game of its era, something you may be reminded of when you realize that Gabriel can only use landline phones to communicate over long distances. It’s also reflected in the gameplay: To solve many puzzles, it’s advisable to pay careful attention to every line of dialogue.

Adventure games from this time were meant to keep you playing for many, many hours—if you still got stuck, the expensive hint line was waiting to take your call. This being a Sierra game, you can very much die (especially in the second half), so saving the game often is a good idea.

The racial politics of Gabriel Knight are more troubling. While the story incorporates historical facts about Louisiana Voodoo, the increasingly preposterous narrative follows an all too familiar trajectory in which a white hero (Knight) must overcome forces of evil, who happen to be people of color. That it wraps both heroes and villains in a thin veil of moral ambiguity hardly makes this more palatable.

In spite of these flaws, Gabriel Knight deserves recognition as a milestone in video game storytelling techniques, and is still enjoyable to play today. I recommend using the Universal Hint System over a walkthrough, as it will give you more opportunities to discover solutions to puzzles on your own. The soundtrack has held up well, and adds to the game’s atmosphere and character.

A 20th anniversary remake with new graphics—and a wholly different voice cast—was released in 2014. While Gabriel Knight deserves its place in video game history, I’m not sure it needed a remake. There are new stories to tell, and new heroes to play—ones that challenge stereotypes rather than reinforcing them.

“And when they knew the Earth was doomed, they built a ship.” In one opening sentence, John Ayliff’s text-based browser game Seedship evokes stories of the journey to another world, of efforts to settle a new planet while avoiding the mistakes of the past.

1,000 colonists are all that is left of the human race, and they are asleep in hibernation chambers. You control a shipboard Artificial Intelligence that is meant to find a new home for humanity—a mission that will take thousands of years to fulfill.

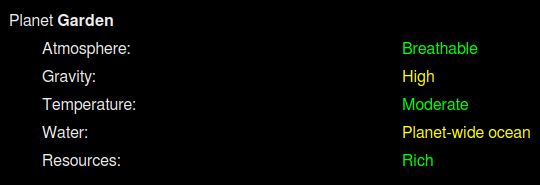

You travel from one planetary system to the next, and you use scanners and surface probes to determine the suitability of candidate planets for human settlement. Does the planet have a breathable atmosphere, Earth-like gravity, tolerable temperatures, sufficient water and other resources?

Planets may hold other surprises for the colonists, from poisonous plants to high-tech ruins of previous civilizations. Based on all available information, you can decide to found a colony, or to keep searching.

Risks and Rewards

Every part of the ship, including the hibernation chambers, may be damaged during interstellar travel. On the other hand, you also have opportunities to upgrade your ship, which may improve your odds of finding a suitable home.

Ultimately, the success of your mission comes down largely to luck. You may find a lush paradise planet early, or encounter one toxic wasteland after another.

Seedship features no graphics, but its text-based interface, such as the scan results shown here, manages to convey a lot with few words. (Credit: John Ayliff. Fair use.)

What makes the game so enjoyable is the quality of the storytelling. Ayliff has stocked Seedship with many random events, from encounters with alien spaceships to the discovery of a brutal dictator among the sleeping colonists. Your choices (eject the dictator or let him sleep?) almost always have consequences, but those are often unpredictable.

When you decide that you’ve found the perfect (or at least adequate) new home for humanity, Seedship tells you about the fate of the colony. Did humanity maintain its previous level of technological achievement, or regress to a medieval level? Is your new society an enlightened utopia, or a tyrannical police state?

A single run can take only a few minutes, but you may find yourself playing Seedship for well over an hour to discover the different possible futures for humanity. If you enjoy sci-fi stories, I highly recommend giving it a try.

Finches are known for their short lifespans, and so are the Finches, the troubled family whose story is at the heart of What Remains of Edith Finch.

You play as the titular Edith Finch, a young woman visiting the family’s haphazardly built home on Orcas Island, which was abandoned years ago. Each sealed room holds the story of a family member’s demise—and you want to know all the stories.

As you experience these individual vignettes, your perspective often changes to that of the family member in question. Perspective should not be confused with control: the game inexorably pulls you towards each character’s final destination.

Barbara’s room, one of the many you explore as part of experiencing the stories of the Finch family. (Credit: Giant Sparrow. Fair use.)

In its wistful, surreal style, Edith Finch is reminiscent of a Tim Burton movie like Big Fish; in its portrayal of a beautifully dysfunctional family, it calls to mind the works of Wes Anderson. But the game never feels derivative; it feels inspired.

Like a movie, it is very much on rails—you may very occasionally wander around for a few minutes wondering how to advance the story, but you’re unlikely to need a walkthrough, and there are no meaningful choices for you to make. That never feels limiting: like Edith, you just want to find out what happened.

There’s so much more to praise here: art direction that reaches soaring heights during some chapters (Lewis’ stands out); excellent voice acting especially by Valerie Lohman (Edith); music that will give you chills; an ending that holds nothing back.

I played the game on Linux using Proton without issues. Steam claims that I played it for 3 hours. The Finches may be short-lived, but Edith Finch will remain with me for much longer than that.

Nina Guerrera (whose name means “warrior girl”) escaped a serial killer’s clutches when she was a sixteen-year-old girl; now she’s an FBI agent hunting predators. Due to a name change after her emancipation from her abusive foster parents, Nina’s would-be murderer was unable to locate her again. Nina was “the one that got away”.

A viral video that shows Nina fighting off a rapist comes to the killer’s attention, and he sets out to finish what he started. But hunting Nina is not enough. The viral video gave Nina the attention he feels he deserves. Through a series of murders, he provokes the FBI into a public manhunt. Soon, he is “The Cipher”, a murderer who leaves behind cryptograms, much like the infamous Zodiac Killer.

The Cipher is a an FBI procedural by Isabella Maldonado, a retired police captain turned crime writer. To make it a story of our times, Maldonado has her killer use social media to turn his crimes into a spectacle. The FBI and the social media sites collaborate to keep the killer online, in hopes of tracking him down.

What if Zodiac Killer, but on Facebook?

This leads to wildly implausible plot developments, where “The Cipher” maintains a public leaderboard on his Facebook page, ranking the amateur investigators around the country who try to break his (often very simple) codes. Similarly, he is permitted to repeatedly post videos of horrific crimes to an audience of millions.

If you can believe that, you will probably not have an issue with the book’s more conventional tropes, such as the idea that an FBI agent would be allowed to lead an investigation while being very publicly threatened with rape and murder by its target, who previously raped and almost killed her.

Maldonado moves the plot forward at a steady clip, and The Cipher is certainly an easy read—I read most of the book on a transcontinental flight, and downloaded it for free through Amazon’s “First Reads” program. Maldonado deserves credit for writing in a very accessible manner, e.g., about investigatory procedures; she also sometime subtly repeats important plot points to help the reader along.

These are the kinds of writing techniques that make this book a page-turner. The positive reviews the book has received suggest that many readers found it thrilling. Maldonado has already written one additional novel featuring Guerrera, and there are plans for a Netflix adaptation of The Cipher.

For me, the many plausibility issues make it difficult to recommend the book, in spite of a likable heroine.

A spider-like extraterrestrial emerges from a spaceship parked in front of the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto, enters the museum, and requests to speak with a paleontologist. It’s a great opening for Robert J. Sawyer’s Calculating God, a story mostly told in the first person from the point of view of said paleontologist, a man with the ominously biblical name Thomas Jericho.

The alien, who is named Hollus, reveals quickly that their species, the Forhilnor, believes the existence of God to be a scientific fact. Hollus wants to learn more about extinction events in Earth’s history.

Mild spoilers (click to reveal)

The Forhilnor have found evidence that mass extinction events have occurred at approximately the same time on multiple planets now inhabited by intelligent life—apparently including the extinction events in Earth’s history. In addition, they believe that the evidence for a universe fine-tuned to support life cannot be explained except by an intelligent designer.

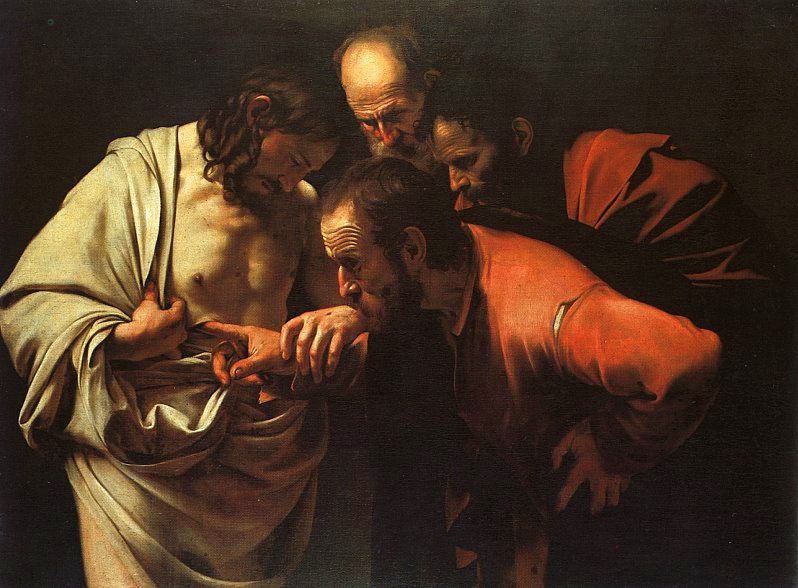

Thomas Jericho is a staunch atheist, but Hollus is not religious in the conventional sense. The two scientists become friends as they study the fossil record of Earth and other planets. Will Doubting Thomas come around to see the evidence of the designer? And what are two American anti-abortion terrorists planning to do in Toronto?

Like Saint Thomas (depicted in this painting by Caravaggio), Tom Jericho demands strong evidence before accepting extraordinary claims.

Intelligence by Design

In exploring the evidence for God, Sawyer stacks the deck in favor of a designed universe. In addition to made-up discoveries by the extraterrestrials, he revisits creationist canards like the idea of irreducible complexity, of “missing links” in the fossil record, and of lack of evidence for speciation.

The book was published in 2000, and as Sawyer has stated, he was influenced by neo-creationist literature such as Michael Behe’s “Darwin’s Black Box”. This was before Kitzmiller v. Dover, a key lawsuit in 2005 which set back the so-called Wedge Strategy to use the pseudoscience of “intelligent design” as a backdoor to introduce creationism into schools.

But even in 2000, plenty of scientists and skeptics had extensively debunked the arguments Sawyer has his characters regurgitate (see, for example, the talk.origins FAQs). It’s one thing to invent evidence for an intelligent designer that serves the story; it’s another to rely on pseudoscience. In Calculating God, Sawyer does both.

The Verdict

In spite of this, I found the book more engaging than The Terminal Experiment (review), and less dated. Parts of Calculating God feel like a theater play, a big story told on the small stage of a Canadian museum, with charming characters and a sense of humor and self-awareness.

Hollus, the extraterrestrial visitor, is very memorable: truly alien in appearance but, at the same time, witty and relatable. Their human counterpart, Tom Jericho, comes to life in small details such as his political disagreements with the museum’s administration. The friendship between Jericho and Hollus is believable and carries much of the book forward.

Ultimately, however, Calculating God takes itself too seriously. In the last third of the book, increasingly implausible events lead towards an ending that is only a poor imitation of works that have surely inspired it, such as Carl Sagan’s Contact and Arthur C. Clarke’s 2001: A Space Odyssey.

In his podcast, LeVar Burton (Reading Rainbow, Star Trek: The Next Generation) reads one short story per episode. Burton’s masterful narration is enhanced by music and sound effects. He features stories by well-known writers (e.g., Neil Gaiman, Octavia Butler), but he and his team also seem to be constantly on the lookout for fresh and diverse new voices.

Burton is incredibly talented, and he manages to bring across a sense of excitement and wonder for every story. He invests himself deeply in making the characters come alive, drawing on his decades of acting experience.

While many of the stories could be described as “speculative fiction”, there’s no single unifying theme other than LeVar Burton’s love of story. There are ads at the beginning and in the middle, read by Burton. I typically skip through those, but they are not especially obnoxious. LeVar Burton Reads is one of the shows under the Stitcher umbrella, and you can listen ad-free with a Stitcher subscription.

At the end of each episode, LeVar Burton reflects on the story and relates it to his own life or to what’s going on in the world. Sometimes he’s clearly just riffing, sometimes he has a larger point he wants to make. Either way, it’s often a nice way to close out the episode.

If you like fiction and podcasts, you’ve probably already subscribed to LeVar Burton Reads. If you haven’t, I cannot recommend it highly enough. Some of my favorite stories include:

-

Vaccine Season by Hannu Rajaniemi, about life and death in a world close to the elimination of all illness.

-

The Water Museum by Nisi Shawl, about an assassination plot against the curator of a most unusual museum.

-

Silver Door Diner by Bishop Garrison, about a consequential conversation between a waitress and an alien.

-

Staying Behind by Ken Liu, about a world divided between those who embrace a life beyond the human body, and those who reject it.

-

Room for Rent by Richie Narvaez, about a future in which humanity is widely regarded as an annoying pest by other, more powerful species.

You’re likely to discover your own favorites in the large back catalog of episodes. While the show is still going strong as of this writing, LeVar Burton Reads is also a timeless, wonderful library that you’ll keep coming back to.

Trüberbrook is a 2019 point and click adventure game set in a fictional eponymous small town in late 1960s Germany. You play as Hans Tannhauser, an American quantum physics student with German ancestry, who has won a vacation to Trüberbrook (without entering any contest!).

During the first night in his hostel, Tannhauser’s notes on quantum physics are stolen. As he starts tracking down the thief, the evidence points to an abandoned mine, and he soon pairs up with a visiting paleoanthropologist named Gretchen Lemke who is also seeking to explore it. What is the connection between the mine and Hans’ work in quantum physics?

What stands out the most about Trüberbrook is its unique visual style. All backgrounds are based on digitized miniatures, enhanced by in-game lighting and shadow effects. The 3D character models aren’t photorealistic; they look more like clay figures, which works well enough in this setting.

Trüberbrook’s unique aesthetic is the result of the digitization of painstakingly hand-crafted miniatures (Credit: btf. Fair use.)

The gameplay is classic point-and-click adventure fare (walk around, pick up stuff, talk to other characters, combine items), with a simplified inventory system. For example, if you have a screwdriver in your inventory, and you want to unscrew a TV set, you click on the TV set, and the screwdriver becomes available as a possible interaction.

This reduces the “combine everything with everything” aspect of many adventure games, but it would have been nice to at least be able to explore your inventory (it’s only optionally displayed as an icon bar, without descriptions).

The game’s lovingly created visuals can’t help Trüberbrook to overcome mediocrity in most other areas: storytelling, character development and puzzle design. To name an example in each category:

-

Storytelling: In an early chapter, Hans must escape from a medical facility. But the game never fully resolves why he was kept there in the first place.

-

Character development: While Trüberbrook has its share of quirky characters, the game’s protagonist is almost entirely without personality, and the motivations of its villain are poorly explained.

-

Puzzle design: In one puzzle, you obtain an important item by ordering a beer at the hostel reception. But the option to order a drink only becomes available after you exhaust all other (unrelated) dialog options.

There are exceptions, of course—the game has a few truly delightful, clever and funny moments. With more time spent on everything other than its visuals, it could have been a great game. As it is, if you find the visuals and setting appealing, you may wish to pick it up on sale and keep a walkthrough handy to keep frustrations to a minimum.

I was 16 years old when The Terminal Experiment by Robert Sawyer was published in 1995. This was the time when the Internet was starting to break into the mainstream, and everyone was trying their hands at predicting its impact. In Newsweek that year, Clifford Stoll famously wrote:

The truth in no online database will replace your daily newspaper, no CD-ROM can take the place of a competent teacher and no computer network will change the way government works.

How does a Nebula-winning sci-fi novel from 1995 about mind uploading, artificial intelligence, and morality hold up in 2021? In the case of The Terminal Experiment: not too well.

Sawyer’s vision of the 2000s and 2010s is, unavoidably, a mix of correct predictions (e-readers are commonplace), false extrapolations (CompuServe seems as important as the Internet) and unlucky guesses (instead of buying a newspaper, print it on demand!). But more than its future past, the book’s story will challenge any reader’s suspension of disbelief.

Soul search

The protagonist, Peter Hobson, is a Canadian biomedical engineer who has devised highly sensitive brain scanning equipment (a “superEEG”) to determine the exact moment of a person’s death. But the superEEG picks up something else: a pattern of brain activity—an electrical field—that leaves the human body after its death.

Has Hobson found evidence for life after death, and if so, what’s the nature of this afterlife? If given a choice between physical immortality or the hereafter, which should we prefer? It’s a timely question in Hobson’s world, as a California firm called “Life Unlimited” has begun marketing nanotech life extension techniques that promise practical immortality for all intents and purposes.

Luckily, Hobson’s best friend Sarkar Muhammed is an AI expert who has also tried his hand at mind uploading using Hobson’s brain scanning equipment. It’s still an experimental technique, of course, but Hobson volunteers to have three copies (simulations or “sims”) of his mind created:

-

an unmodified copy (the control);

-

a mind that perceives itself to be immortal but still human;

-

a mind that perceives itself to be a disembodied spirit, with no worldly concerns.

The friends’ scientific inquiry is disrupted when one of the sims appears to commit a grisly murder. Hobson and Muhammed find themselves in a race with the police to find out what happened, and which of the sims (if any) is responsible. Can the two plucky Canadians solve the mystery and prevent further killings?

Philosophy first

I’ll spare you any spoilers, but honestly, it would be hard to spoil the book—the major plot points are fairly predictable, and I say that as someone who is probably more oblivious to such things than the average reader.

The Terminal Experiment puts its philosophical premise above everything else (plot, characters, worldbuilding). Even its protagonist, Peter Hobson, is named for Hobson’s Choice, which relates to the book’s central premise. (In case you didn’t guess that, the book helpfully tells you so, repeatedly.)

The conversations Hobson and Muhammed have with the three copies of Hobson’s mind are the most engaging part of The Terminal Experiment. I found Spirit in particular (the copy that imagines itself to be in a kind of afterlife) to be the book’s most interesting character.

Because it explores some interesting philosophical questions, Sawyer’s book is not without merits, but if you had it in your backlog for a while, I wouldn’t recommend it for anything other than a lazy afternoon or a long plane trip.