Reviews by Eloquence

Vampire Survivors by indie developer Luca “poncle” Galante was released in December 2021. It only costs $3 and is still in early access, but has already racked up tens of thousands of “overwhelmingly positive” reviews on Steam.

The game’s formula is simple but brilliantly executed, once you look past its rudimentary 16-bit style pixel graphics. Your goal is to survive for 30 minutes against ever-growing mobs of monsters. You start with a single weapon, but as you defeat monsters, you level up quickly. So far, that sounds like many twin-stick shooters.

The game-changing part of the Vampire Survivors formula is this: There’s no need for button-mashing, as your character auto-fires all weapons at their maximum firing rate.

As someone who quickly gets controller fatigue from many action games, I found it surprisingly chill to play, in spite of the amount of stuff happening on the screen. You avoid enemies, destroy them with an ever-growing arsenal of weapons, collect experience gems, and level up.

Power-ups from hell

Level up enough, and the game’s promise that “you are the bullet hell” becomes fulfilled. It’s hard to convey just how insane things can get. Consider that this shows only a mid-level build:

Character “Krochi” facing an onslaught of monsters in the first stage. (Credit: Luca Galante. Fair use.)

To make it through 30 minutes, you need to continually improve your build, and combine items into ultra-powerful “evolved” weapons. You can also use collected coins from a run to buy persistent power-ups that will help you with all future runs.

It won’t take you more than a few hours to master the first stage, but Vampire Survivors has lots more to offer. You can unlock many different characters (who may have their own unique weapons), additional stages, and additional difficulty levels.

While the maps are generally super-simple, there are a few surprises. For example, the “Dairy Plant” map features new mechanics, such as little carts you can push in the direction of oncoming enemies, and special floor tiles that trigger enemy waves to spawn.

Challenging but not limitless

Even though it is still in early access, Vampire Survivors easily offers 10-20 hours of frantic play as of this writing; content updates have been forthcoming at a rapid clip. If you like action games and don’t find the visual intensity offputting (or worse), you’ll definitely want to check it out.

Unlike roguelikes that offer nearly endless challenges, most players will eventually hit a ceiling as they accumulate persistent power-ups and develop ever-more successful builds. But for $3, that’s still a hell of a lot of entertainment (no pun intended), and anyone trying the game now should revisit it again in a few months as it continues to be expanded and balanced.

I played Vampire Survivors on Linux using Proton without issues (I did have to set the launch options to PROTON_LOG=1 %command% as recommended on ProtonDB).

Additional reading

-

In February, NME published a nice interview with developer Luca Galante.

-

As usual, a Fandom wiki has quickly popped up; if you don’t want to discover every combo for yourself, the weapons evolution guide in particular is indispensable.

What if you took some of the best ideas from the roguelike deck-building genre, but instead of being dealt cards, you rolled dice on each turn? That’s the premise of a ridiculous, addictive, and sometimes frustrating game called Dicey Dungeons.

Developer Terry Cavanagh has published indie games since at least 2008, but his breakthrough titles were the puzzle platformer VVVVVV (2010) and the brilliant twitch game Super Hexagon (2012).

When I first looked at Dicey Dungeons, I was not especially enamored. Anthropomorphized dice, really? The moment you start actually playing it, the game’s self-aware sense of humor makes it all work.

You play as the contestant in a gameshow whose host, Lady Luck, promises to fulfill your innermost desires if you win. The catch? You’re transformed into a dice and are doomed to compete in Lady Lucks’s dungeons forever, with the game clearly rigged against you.

Revenge of the bloodsucking vacuum cleaners

The maps are the least interesting part of the game, but they do show you all the enemies you can fight in a given level. In this case, you can go up against a marshmallow, a coin-stealing kid, and a sickly hedgehog. (Credit: Terry Cavanagh. Fair use.)

The enemies you encounter are not the standard fantasy fare. Instead, your next opponent could be a bloodsucking vacuum cleaner, a snowball-throwing yeti, a poisonous ice cream cone, or a guy whose entire head is a home stereo system.

Battles are turn-based. On each turn, you roll a number of dice, which you then drag and drop to a compatible item in your inventory. You may not have one! For example, all your items might require even numbers, and you might roll a bunch of threes.

It’s a simple enough concept, but with a large variety of enemies and items, it adds up to a rich gameplay experience. By itself, that could make for a 5-10 hour game. What makes Dicey Dungeons a 30-60 hour game is its willingness to throw its own rules by the wayside.

Rules, schmules

As you play the game, you unlock new characters with their own sets of items, and with completely different play styles. For example:

-

a character that casts spells from a spellbook with a fixed number of slots, of which up to four can be active at any given time.

-

a character that, instead of rolling dice, generates random numbers towards a fixed target value. If you hit that target value exactly, you get a jackpot reward.

-

a character that is dealt a set of cards in random order, combining true deckbuilding mechanics with dice.

Moreover, each character advances through six episodes that play with rules in interesting ways. The most interesting of these are the “parallel universe” episodes (in which items and status effects work completely differently) and the bonus episodes (in which you gradually accumulate randomized rules like “after 4 turns, all enemies transform into bears”).

It all culminates in a final confrontation which, again, does something completely new and interesting with the game mechanics. I won’t spoil it for you; suffice it to say that there’s a lot to keep the player engaged. And when you’re done with that, there are some (fairly easy) Halloween bonus episodes as well.

As with Super Hexagon, Cavanagh again collaborated with Chipzel on the music. Unlike the high octane chiptune sound of Super Hexagon, Dicey Dungeons’ soundtrack blends in jazzy flavors, which give the game a unique feel.

The game’s wit and humor come through in many places, such as when visiting shops. Sometimes the shopkeepers will even remark on specific enemies in the level you’re in. (Credit: Terry Cavanagh. Fair use.)

Dice with rough edges

The game is not perfect. My criticisms of it can be summed up in three categories:

-

Pointless maps: The game features suitably atmospheric levels such as “the libary” or “the dark forest”. But the actual dungeon maps are extremely linear and basic. The most complex choices you’ll make navigating the dungeon are branching questions: This enemy first, or that one?

-

Luck over strategy: Being at its heart a dice game, Dicey Dungeons can be incredibly unfair. An enemy can roll two sixes twice in a row, hitting you with maximum damage and status effects, while you are barely able to make a dent due to a poor roll.

In theory, you can sometimes flee a battle. But that action is almost useless. You’ll still have all your damage, and in many cases you won’t progress unless you defeat the enemy. So, go against the same enemy again with three hit points left, while they’re back at full strength? Good luck! -

Inconsistent execution quality. The spellbook user experience, for example, is very clunky—the drag and drop mechanics are poorly explained and not intuitive. Even though the mechanic had promise, I had the least fun playing that character, just due to the interface feeling so unpolished.

Each character’s list of episodes includes an “elimination round” which, as the name suggests, exists to prevent straightforward progression. It achieves this by making the enemies’ items a lot more powerful. Unfortunately, this can lead to a high number of unwinnable encounters.

The Verdict

Those criticisms shouldn’t distract from the fact that Dicey Dungeons, overall, is a hell of a lot of fun to play. There’s a lot of love in the details, from the silly unlockable enemy biographies, to the clever dialogue during encounters or shopkeeper visits.

I would give the game 4.5 stars, rounded up because of the sheer amount of gameplay variety and content. If you enjoy the deckbuilding formula, and are looking for something similar that may keep you entertained for a few weekends, go and roll those dice—you might get lucky!

The explosion of indie gaming in the 2010s has blessed players with the triumphant return of genres largely written off by major publishers, from 16-bit-style “metroidvanias” to point-and-click adventures. The flip side of this blessing is the problem of discovering the indie gems you truly want to play. That’s where Hardcore Gaming 101’s Guide to Retro Indie Games comes in.

On 152 richly illustrated pages, the first volume presents detailed overviews of many games which, while mostly released in the 2010s, seemed “retro-styled” to the editors. It is, as they acknowledge, a squishy definition:

It’s primarily to refer to games that would be inviting to fans of classic video games, rather than a specific style. For example, even though Night in the Woods doesn’t have a pixel look, it’s still recommended for adventure game aficionados.

To be sure, you won’t find on these pages the kinds of indie games that are going head-to-head against big-budget, “triple A” open world RPGs or first-person-shooters. If there is going to be a shooter, it’ll be a “boomer shooter” in the style of the original 1990s trailblazers like Doom or Duke Nukem.

Straight to the point

The guide focuses on gameplay above all else. Don’t look to this volume for information about the developers, how the games were made, or technical details. The tiny infobox about each game contains its title, the year it was published, and the platforms it’s on—that’s it.

The platform list at least is exhaustive, condensed into three letter abbreviations ranging from the obvious (“WIN”, "PS4”) to the obscure (“AFT”, “PAN”). Thankfully, there’s a system key on the first page.

Each article is somewhere between a review and an overview, and seems intended to help the reader answer two questions: How good is it, really? And, is this game for me?

Games are typically described in two pages, and every single page is richly illustrated. (Credit: Hardcode Gaming 101. Fair use.)

On the whole, I found the articles fair and informative, helping me prioritize my backlog and discover some new games. In a couple of cases, the articles went a little too close to spoiler territory for my liking, but that can be hard to avoid when writing about a story-driven game like Lisa or Undertale over multiple pages.

Not a true guide, but still a great introduction

To be truly a guide rather than a collection of articles, the Guide to Retro Indie Games would have benefited from some chapter introductions to the developers or the genres represented here. Nonetheless, if you love indie games and enjoy reading about them in print, I definitely recommend it.

One caveat: the first copy I ordered had severe print quality issues. That kind of thing happens especially with small publications, and Amazon quickly sent a free replacement, so it’s not reflected in the review score. I also bought the second volume, which did not have the issue.

The first printed copy I ordered from Amazon had significant color misalignment issues on every page, rendering the screenshots blurry and almost unreadable. (Credit: Hardcode Gaming 101. Fair use.)

The full list of games in the first volume follows (grouped by publisher):

The Shivah

The Blackwell Series

Gemini Rue

Resonance

Primordia

Technobabylon

Shardlight

Kathy Rain

Thimbleweed Park

Nelly Cootalot

Always Sometimes Monsters

Read Only Memories

Va-11 Halla

Night in the Woods

Pony Island

Mercenary Kings

Flinthook

Odallus

Oniken

Noitu Love

Rogue Legacy

Super Time Force

Volgarr the Viking

Freedom Planet

Westerado

VVVVVV

Shovel Knight

Super Meat Boy

Ultionus

Mystik Belle

Guacamelee!

Axiom Verge

Owlboy

Dust: An Elysian Tail

Hyper Light Drifter

Alwa’s Awakening

Undertale

Lisa

Barkley, Shut Up and Jam: Gaiden

Severed

One Finger Death Punch

Not a Hero

Assault Android Cactus

Hotline Miami

Crimzon Clover

Blue Revolver

Hydorah

l’Abbaye des Morts

Maldita Castilla

The Curse of Issyos

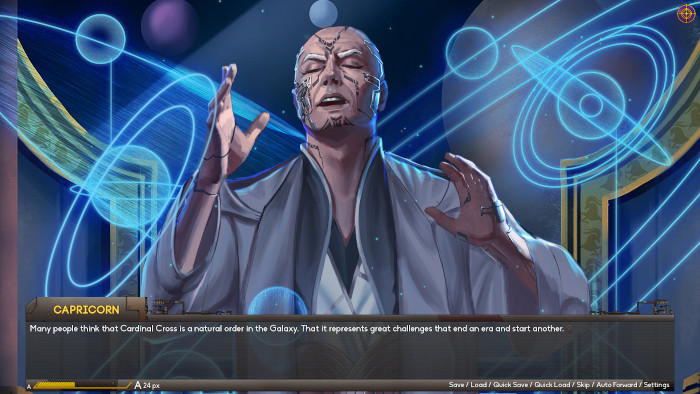

Cardinal Cross is a choice-driven visual novel about a space-traveling scavenger named Lana Brice, who unexpectedly finds herself caught up in a galactic conflict of an astrological nature. The game was written by Roman Alkan and published through her small indie studio LarkyLabs under its ImpQueen brand.

In this universe, predictions derived from the movement and position of celestial objects are as fictionally real as the Force in Stars Wars, or as the fungal excretions of sandworm larvae that make interstellar travel possible in Dune. In most other ways, Cardinal Cross employs familiar sci-fi tropes: cybernetic implants, space rebels, robots and AI, the works.

Lana Brice (left) is a space scavenger with strained family ties. (Credit: LarkyLabs. Fair use.)

Meet the factions

Lana Brice and her friend Wiz, the Mechanic, are part of group of planets known as the Raiders. These folks have gotten the short end of the stick in a conflict with another group known as the Morai System, and they’re generally treated like colonies.

In a black market transaction, Lana and Wiz come in contact with a rogue intelligence agent of the Morai, who is trying to purchase an artifact from them. Most people have cybernetic implants, but this guy is enhanced to the point of almost losing his humanity. He is dangerous, and so are his former employers.

Soon enough, Lana is caught up in a web of conspiracies and plots involving multiple factions. At its center is an astrological supercomputer which the Morai elite use to maintain power and control. Its predictions are not perfect: so-called “howlers”—some humans, objects, planets—elude it completely. (I’m guessing the term is a reference to errors and aberrations rather than monkeys.)

As you might expect from its astrological theme, much of the story revolves around whether our fates are our own to write if the stars seem to already foretell what they are. Thankfully, the story never gets bogged down in sophomoric arguments about free will—it plays out more viscerally through Lana’s choices. That is to say, your choices.

One way or another, Lana’s fate is in the stars. (Credit: LarkyLabs. Fair use.)

Choices and characters

Throughout the story, you get to make more than 100 decisions, typically about things to say, sometimes about things to do. A lot of them have a negligible effect, but you can romance three different characters, influence Lana’s personality, and achieve multiple endings.

The game signals the most important choices with a sound effect, and it makes it clear when you have the option to embark on a romantic adventure. It also displays the effect you have on others (“[name] is annoyed”, “[name] is amused”). These messages are sometimes off-point and immersion-breaking, but you can disable them entirely.

Cardinal Cross is not voice-acted, but it is exceptionally well-illustrated. Not only does it have beautiful character art, it has a ton of it.

There are 50+ side characters, and most of them are visually well-differentiated. It includes 70+ full-screen graphics during special events (“CGs” in visual novel lingo). In case you’re wondering: the graphics for the romantic outcomes are about as tame as what you’d find in a PG-rated movie.

The game has a soundtrack by Jeaniro, which creates suitable ambience without distracting from your reading experience. During the story’s most dramatic moments, the music becomes boisterous or tense, generally fitting the text well.

The story is substantive, but it doesn’t overstay its welcome. I reached an ending which suited my choices well in about 6 hours. After I checked out one other ending with the help of a guide, my total playtime added up to 8 hours.

A good yarn with a few flaws

Roman Alkan’s world-building helps to set the stage effectively, even if the introduction of the in-universe terminology is a bit tedious at first. I had three main issues with the writing:

-

It would have benefited from more editing (there’s some dialogue that’s a bit awkward; there are a few spelling/grammar issues throughout).

-

There are too many characters to keep track of, and the story shifts too quickly between them.

-

Relatedly, the story doesn’t give enough space to some key dramatic moments for us to really grapple with what just happened.

Know that it’s a violent game. Both Lana and the other characters may hurt—and kill—people they come across. Cardinal Cross does not explore its darker themes with the same sensitivity some visual novel writers (like Christine Love) bring to their work; here, transgressions don’t always have the reverberations you would expect.

All in all, though, it’s a good yarn. It riffs on the astrology theme in a way that I’ve personally not encountered in sci-fi (astrology is still annoying, don’t @ me!). It’s a great example of the art form, bringing graphics, music and writing together into a coherent whole. I would enjoy reading about the further adventures of Lana Brice, and will definitely pay attention to ImpQueen’s future works.

As if Aidan didn’t already have his hands full! Now his father has gone missing. The single, unemployed dad of a highly energetic little daughter is barely out of bed when he begins to discover the first clues in his father’s workshop as to what may have happened.

What on Earth is “Clonfira”, and what do the strange patterns on the wall mean? Suffice it to say that Aidan’s father has discovered a way to visit another world, and Aidan and his daughter will soon follow in his footsteps.

The Little Acre by Irish indie developer Pewter Games is a point-and-click adventure. The game’s credentials are boosted by Executive Producer Charles Cecil, a grandmaster of the genre (Lure of the Temptress, Broken Sword).

Worlds brought to life

You play as Aidan and as his daughter Lily. The controls are as simple as it gets: you click on hotspots and sometimes combine items in your inventory with what’s currently on the screen. Many puzzles are contained within a single scene, keeping typical point-and-click frustrations (backtracking, a large inventory) to a minimum.

Most puzzles make sense at least in retrospect, even if you sometimes have to behave nonsensically to progress (scare a cat → cat smashes flower pot → smashed flower pot reveals hidden item you need). Built-in hints may help if you do get stuck.

Once Aidan enters the alternative dimension where his father may have gone missing, he transforms into a chibi (small and cute) version of himself. (Credit: Pewter Game Studios. Fair use.)

The game’s worlds are brought to life in excellent art and animation. Whenever you solve a puzzle, you’re likely to see a fully animated little scene. Even when you’re not doing anything, much of the game is visually captivating, and the world feels alive. Some cut scenes are almost of cinematic quality.

The game’s music is catchy and enjoyable, albeit a bit repetitive. The Little Acre is fully voice-acted as well. For some reason, the two main characters narrate their actions in the past tense, which doesn’t always make sense. There are no dialog trees and few interactions between characters.

A rushed adventure

It’s all over very quickly: a full playthrough is likely to take you between 1-2 hours. Some adventure games manage to deliver a powerful experience in a short playtime (think Loom or the more recent What Remains of Edith Finch). The Little Acre unfortunately feels very rushed.

Scenes that should have emotional power aren’t given the room they need. The villain’s motivations are insufficiently explained. A new character is introduced but given very little to do. Switches between Aidan and Lily happen too quickly. The ending is abrupt and delivers limited emotional payoff.

At the same time, the game’s amusing animations, cutely drawn characters, and relative simplicity make it a good family activity, if you don’t mind that it also deals with grief and loss. Kids may be more ready to forgive the game’s weaknesses, and to fill in the blanks with their own imagination.

Overall I would give The Little Acre 3.5 stars, rounded up because Dougal the dog is a very good boy. It’s often on sale for $5 or less, and that’s a good price to pay for it.

Technical notes:

The game has a native Linux version. It crashed for me a couple of times, but auto-saved at the beginning of each scene, so I did not lose any progress.

To the Moon (2011) is one of the most beloved indie narrative adventure games of all time. In it, two scientists travel into a dying man’s memories to fulfill his final wish. Into A Dream (2020), created by solo developer Filipe F. Thomaz, has a similar premise.

You play a man named John Stevens who finds himself in the dream world of another man, Luke Williams. Luke appears to be experiencing a mental health crisis, and you receive a message from the outside world tasking you with investigating its origins.

One of the unfortunate side effects of the dream insertion procedure is that John doesn’t have access to his own memories. So, just like the player, he knows nothing about the people he meets or the specifics of Luke’s life. John meets him and his family at different points in their lives.

Luke, it turns out, is an entrepreneur who is pursuing a vision of ubiquitous renewable energy. Exhausted by work, he reaches his breaking point after the early death of his mother. His wife Rita and his daughter Anne pay the price as Luke grows increasingly distant from them.

Platforms in the way

You view the dream world from its side, and everything is rendered in silhouette, as in a shadow play. As is typical for narrative adventure games, you spend a lot of time talking to characters you meet. The game also has simple platformer sequences (jump & climb), inventory fetch quests, and one puzzle that depends on precise timing.

The game’s action sequences and puzzles are rarely clever or original—they serve as speedbumps that prevent you from rushing through the story. Into A Dream lacks the qualities that make a great platformer (quick animations, optimized hit zones, responsive controls), so this is the single most frustrating aspect of play. Fortunately, you can’t die permanently, and you can save and resume anywhere.

Into A Dream makes excellent use of changing background colors, lighting, and other effects to convey the sense of an unstable yet beautiful inner world. The game is accompanied by Thomaz’ piano music, which suits the game’s atmosphere well. The presentation falls short in other ways.

When it doesn’t get in its own way, the game depicts a world that is suitably dreamlike, at times serene and beautiful, at times shockingly unstable. (Credit: Filipe F. Thomaz. Fair use.)

Inconsistent execution

Close-up views of objects (such as a children’s doll or a tombstone) look amateurish. Characters you meet are only rendered in one or two poses. For example, you’ll always encounter Luke’s wife sitting cross-legged or talking on the phone.

Animation is in short supply, too. Nobody other than you ever moves around—they just dissolve when a scene ends. The presentation gets in the way of the gameplay when you have to figure out what to do next: Where’s the exit? What’s that black object in the foreground? Can I interact with that door?

The game is fully voice acted by a diverse cast, at varying levels of quality: sometimes energetic, sometimes inaudible, sometimes overwrought or cartoonish. Given the game’s tiny budget (it raised less than $3,000 in an Indiegogo campaign), it would be unkind to be too critical here.

I found the story engaging, and the writing is generally good. There are a few spelling and grammar errors that could have been caught (such as the repeated spelling “murdured” instead of “murdered”), and a simplistic heaven/hell theme in the late game that distracts from the main story.

The Verdict

Into A Dream immerses the player in a world that is at times tantalizingly beautiful, but it frustrates them with clunky platformer sequences and immersion-breaking inconsistencies in its presentation. For a work mainly driven by a single developer, it’s an impressive achievement regardless, and I’ll certainly be interested in Thomaz’ future work.

I wouldn’t recommend Into A Dream at its full price of $15, but discounted below $5 it’s an interesting enough experience over 3 hours or so, if you’re willing to forgive its more frustrating parts. 3.5 stars, rounded down because of one especially annoying stealth sequence in the late game.

Titles like Spiritfarer and Grimm’s Hollow show that imagined afterlives can have immense storytelling power as interactive game experiences. What Comes After by Rolling Glory Jam offers a similar, much shorter fantasy.

You play a young woman named Vivi who falls asleep on the train. When she awakens, she discovers that the train is now filled with spirits destined for “what comes after”. Is she dead? And if not, can the spirits on the train offer her any useful guidance?

The game is structured as a side-scroller, but offers no real choices or challenges. You talk to the beings on the train and move in different directions—that’s it. The whole experience takes about an hour.

Be nice to your houseplants or they’ll lecture you later. (Credit: Rolling Glory Jam / fahmitsu. Fair use.)

That means that the quality of the writing is paramount. Unfortunately, this is where What Comes After falls short. The spirits you talk to share a few sentences about their lives, and may dispense brief platitudes like “Live your life as you see fit and cherish the good people around you.”

Vivi, it is revealed, has struggled with depression and suicidal ideation. These are difficult subjects to tackle, and the game does not do them justice with its fortune cookie wisdom.

What Comes After does offer a couple of sweet moments. You hear the stories of several animals, for example, and encounter a mystical chef who serves very special treats. Some scenes are beautifully illustrated (other scenes are very visually repetitive).

Overall, while it’s clearly a labor of love by a talented team of indie developers, this is one trip to the great beyond you can sit out.

Titles like Slay the Spire (2017), Griftlands (2019) and Inscryption (2021) have defined the genre of roguelike deck-building games where you combat enemies using playing cards. Can small indie studios still bring something new to the crowded genre?

With Meteorfall: Krumit’s Tale, Slothwerks, founded by developer Eric Farraro, is building on the success of its earlier Android/iOS game, Meteorfall: Journeys. Both games feature an art style inspired by Adventure Time and are set in a fantasy world that includes magic, monsters, aliens, and robots.

The intro screen for Krumit’s Tale depicts the outside of Krumit’s cozy house. After you start the game, the aging dungeon-master—who looks like he is part goblin, part elf—quickly invites you in to choose a character and to begin playing a game of cards.

Dungeons are represented by a 3x3 grid of items, abilities, and enemies, with Krumit commenting on your actions in the background. (Credit: Slothwerks. Fair use.)

Dungeons on rails

You find yourself facing a 3x3 grid of cards, which include items, abilities, and enemies. You can discard cards to recover health and to gain coins. You can then spend coins to purchase items and abilities, which are added to your hand of up to four cards.

After cards are removed from the grid, Krumit deals new ones, until there are none left in the deck. Combat is turn-based and driven by simple stats (attack, defense, health). In most cases, you have the first move.

In spite of the title promising a “tale”, there’s little to no story as you advance from dungeon to dungeon randomly. Krumit himself is quite chatty and comments on many of your actions with one-liners; he also introduces bosses when they appear on the board.

As is typical for the roguelike genre, death is permanent. This makes for very tight “runs” that typically last 20-40 minutes.

One of the weaknesses of the game is that you don’t get to choose where the journey goes: Krumit navigates the map for you. (Credit: Slothwerks. Fair use.)

Deceptive simplicity

The game quickly introduces its core mechanics, while providing concise on-screen explanations for all cards. Each of the five unlockable heroes has access to a different set of abilities and items, forcing completely different play styles.

The wizard can burn enemies from afar, causing them to take damage as they move down the grid. The necromancer turns enemies into tombstone cards, which he can then raise to fight in his stead. The rogue is weak, but gains stealth against enemies with no neighbors on the board.

Enemies are similarly varied, from robots that self-destruct to town guards that prevent you from using melee weapons until you defeat them.

To knock out the most powerful bosses, you need luck on your side, but the game also requires strategy to make the best of the cards you’re dealt. After each victory, the game awards you with gems depending on how well you did. You can use these to purchase higher quality cards for the next dungeon.

The Verdict

I am really enjoying my time with Krumit’s Tale and have added it to my list of evergreens that I’m likely to return to time after time. Overall, I would give the game 4.5 stars, rounded up. Its core strengths are:

-

Excellent game design. There’s very little fat here—no tedious tutorials, no nested menus, no complicated rules. Krumit’s Tale is very easy to pick up but difficult to master; you’ll incorporate many new systems and strategies into your play as you go.

-

Gorgeous art direction. Heroes and enemies are lovingly drawn and animated; items are recognizable and distinct. If you like the Adventure Time art style, you’ll feel right at home—much credit to artist Evgeny Viitman.

Krumit himself (voiced by Adrian Vaughan) adds character and flair as well. After more than 10 hours of play, I’ve still not turned on the user preference to make him less chatty! Only the music, which sets a fitting tone of mystery and adventure, gets a bit repetitive. -

Attention to detail. Dungeons and items are accompanied by short but amusing quotes and descriptions. Little indicators appear in the user interface when you gain health or coins. I’ve encountered virtually no bugs and no crashes. Playing Krumit’s Tale feels smooth in the way only the best games do.

The most noticeable weaknesses are:

-

You have no agency about which dungeons to enter—Krumit makes that choice for you. That means you’ll often be dumped in dungeons that you simply have no chance of winning, even with a good strategy.

-

There’s no overarching motive or story. You’re just some adventurer who likes to defeat monsters and collect loot. The enemies, too, seem to have no articulated intentions other than to kill you.

-

As gorgeous as the artwork is, the game doesn’t attempt any real worldbuilding. There are no character sheets for our heroes or more detailed descriptions of the monsters, for example.

The combination of tight gameplay and shallow story is typical for mobile games. As Slothwerks makes the transition to large screen games, many players will expect a more fleshed out experience. Still, I would highly recommend Krumit’s Tale if you find the art style appealing and enjoy roguelike games that can, at times, be utterly unfair.

While I would love to see a native Linux version, I played Krumit’s Tale on Linux using Steam/Proton without issues.

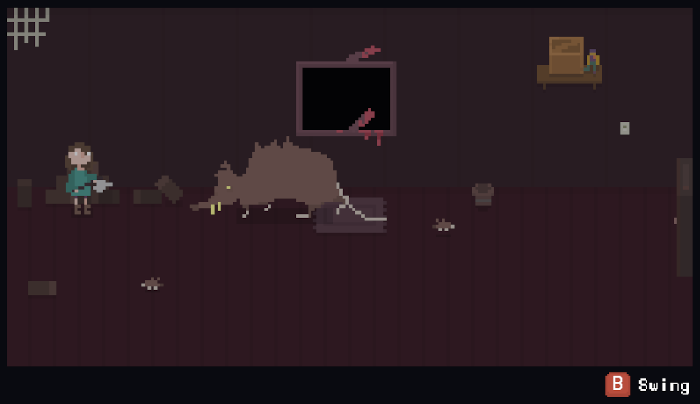

If you’ve ever played one of the classic Sierra point and click adventure games (e.g., Space Quest) and thought “Gee, the one thing this game really needs to be more fun is more random ways to die!”, then House may be your personal game of the year.

You’re a young girl in the eponymous house which is, of course, haunted. Every day you awaken in a home that is newly trying to kill you and your family. Will you save everyone, or will you be the one who does the killing?

The game uses very simple but expressive pixel art, with special attention to death and gore animations. You walk from room to room, pick up items and weapons, and pursue one of the multiple endings. If you die (which you will, many times), you wake up again.

The rodent of unusual size in the basement is the least of your problems. (Credit: Bark Bark Games. Fair use.)

This is an action-adventure—timing and precision do matter. Each run only takes a few minutes, and some aspects of the environment change subtly over time. To survive, you have to make mental (or written) note of what you’ve tried, and where you’ve died.

The game has received many positive reviews on Steam (fluctuating between “Very Positive” and “Overwhelmingly Positive”). I spent about an hour with it before getting frustrated by the repetition and heading to YouTube to watch the endings. Don’t let my experience dissuade you, though. There is a lot to discover in this $5 game, including interesting details about each character—if you don’t mind dying many times in a short loop.

After you die, if your spirit is out of balance, you spend time in limbo as a ghost with too much energy, or as a reaper with too little. Reapers collect the excess energy of ghosts, helping them to pass on—until they have collected enough energy to pass on themselves.

And so is is that a young girl named Lavender finds herself waking up in Grimm’s Hollow as a reaper tasked by the grim reaper (AKA Grimm) with collecting ghosts. Lavender is understandably skeptical of this assignment, but plays along in hopes that she may find her brother Timmy.

Grimm’s Hollow is a freeware indie game by developer ghosthunter, made with the popular RPG Maker software. Much of the game consists of exploring three caves, in which you encounter fellow reapers and fight ghosts in turn-based battles with quick-time events.

The battle-shy baker is tasked by Grimm to accompany Lavender as part of her training as a reaper. (Credit: ghosthunter. Fair use.)

The combat system can be a bit frustrating at first, but once you master it, you’re unlikely to have any issues until the final battle. What makes Grimm’s Hollow a gem of a game is the attention to the story, the worldbuilding, and the characters.

For example, to heal, you collect treats such as “Spooky Cookies” and “Deathlicious Donuts”, all rendered in beautiful pixel art. The baker has made a special deal with Death that he can avoid ghost battles if he just keeps the goods coming.

Grimm’s Hollow features four different endings. If you lose the final battle, make sure to retry until you get at least one of the good endings. The game also offers save slots, but you’re unlikely to need them once you’ve mastered the initial learning curve. All in all, it’s a 3-4 hour experience, and a wonderful treat that should not be missed.

Although this is a Windows game, I played it on Linux using Steam/Proton with only one minor issue: the top GNOME menu bar stayed visible in full-screen mode (without overlapping with the game’s contents).

If you love the game and want to express your appreciation for the developer, you can purchase an art pack on Steam or itch.io.