Reviews by Eloquence

You don’t know what to expect from the odd-looking wooden box which now holds pride of place in your living room. You turn it on and fumble with the controls for a while. Suddenly, the voice of an opera singer pierces the static.

It’s like magic, coming to you through the air, filling the world with possibility and wonder.

What is it like to witness the birth of an invention set to transform humanity? I was not around when radio was invented, but I did experience BBS culture and the early web of the 1990s. It was a time when millions of people were “coming online” for the very first time, without any idea of what that meant. The Internet, as David Bowie put it in 1999, was “an alien lifeform”.

The past that wasn’t

Hypnospace Outlaw is a 2019 indie game that lets you experience the birth of a surreal alternative reality version of the early web. The year is 1999. You are a community enforcer in hypnospace, a web-like network accessed through special headsets people wear during their sleeptime.

You play the game through a desktop environment that looks a bit like Windows 98, macOS and Microsoft Bob were put through a blender. It comes with a browser, an email-like messaging app, a virtual wallet, and a download manager.

You interact with the world of Hypnospace Outlaw through a desktop environment that combines the best and worst of computing around the turn of the millennium. Fortunately, downloads are a lot faster in this simulated reality. (Credit: Tendershoot. Fair use.)

Unlike the web, hypnospace is controlled by a single corporation, Merchantsoft. Its customers can create pages, which are organized into different communities like “The Cafe” and “Goodtime Valley”. On the surface, it resembles web communities like Geocities or its modern-day nonprofit successor, Neocities.

Yet, as the player, you are keenly aware that this is not the early web but an alternative history. You don’t know the rules of this world, but you are tasked with enforcing them. Soon, you receive your first assignment: to trawl hypnospace for copyright violations. Maybe this alternative reality isn’t so different after all…

Much of the gameplay is exploratory: browsing pages, downloading and trying little apps, getting rid of viruses that came with the apps you just tried, and so on. The assignments you receive guide you through the game’s larger narrative and timeline.

Rhythm of discovery

Music is everywhere in Hypnospace Outlaw. The game world is suffused with fictional bands and their creations, from the optimistic MIDI sound of the Millenium Anthem to hyper-commercial, autotuned “coolpunk”; from “Seepage” tracks that sound like Linkin Park demo tapes to the wonderful ridiculousness that is “The Chowder Man”.

The communities you interact with in the game are haplessly curated by the Merchantsoft corporation, though you’ll soon discover corners of hypnospace that have eluded its control. (Credit: Tendershoot. Fair use.)

It really does feel like you’re back in the late 1990s, building a library of MP3 files from dubious sources and trying to figure out what’s actually worth listening to when you can listen to anything.

Amidst the surrealism of it all, the game does have things to say: about commercial control over online communities, about critical thinking, and about the pure joy of free expression in a nascent medium. As I reached the end of the story, I found myself far more emotionally invested than I expected.

The Verdict

I recommend Hypnospace Outlaw without reservations; it truly is a small masterpiece of immersive storytelling. But I would suggest keeping it in your backlog until you have a few hours at your disposal and are ready to fully engage with its world.

This is not a game to rush through, but an experience to savor. As Fre3zer would put it: you gotta “chill it right”.

Imagine you find an alien spacecraft crashed in your backyard. A door has cracked open. You carefully step inside. You discover a world beyond your comprehension. Objects appear before your eyes, only to disappear into thin air. Lights flash in colors you cannot see. It will take humanity’s brightest minds years—decades—to make sense of it all.

Biology is a science attempting to comprehend something no less strange or bizarre: the evolved nano-machinery that constitutes what we call life. We give our discoveries opaque names. Ribosomes. The Golgi apparatus. Neutrophils. When those get too long, we abbreviate. MHC class I and II. ACE2. CD24.

Here lies a wondrous and endlessly fascinating world. Understanding it better could enrich our lives and help immunize us against dangerous pseudoscience. If only we were better at describing this complex, seemingly impenetrable universe inside our own bodies!

Philipp Dettmer is no stranger to making the complex comprehensible. He founded a YouTube channel called Kurzgesagt (“in a nutshell”), which publishes lovingly crafted videos on subjects like wormholes, geoengineering, and brain-eating amoebas. Thanks to brilliant animation, epic music and a dark sense of humor, every video is a treat.

Immune: A Journey into the Mysterious System That Keeps You Alive is Dettmer’s first attempt to bring Kurzgesagt’s trademark educational approach into book form. On 341 pages, Immune sheds light on the incredibly complex macromolecular machinery that protects us against bacteria, viruses, and even snake venom and parasitic worms.

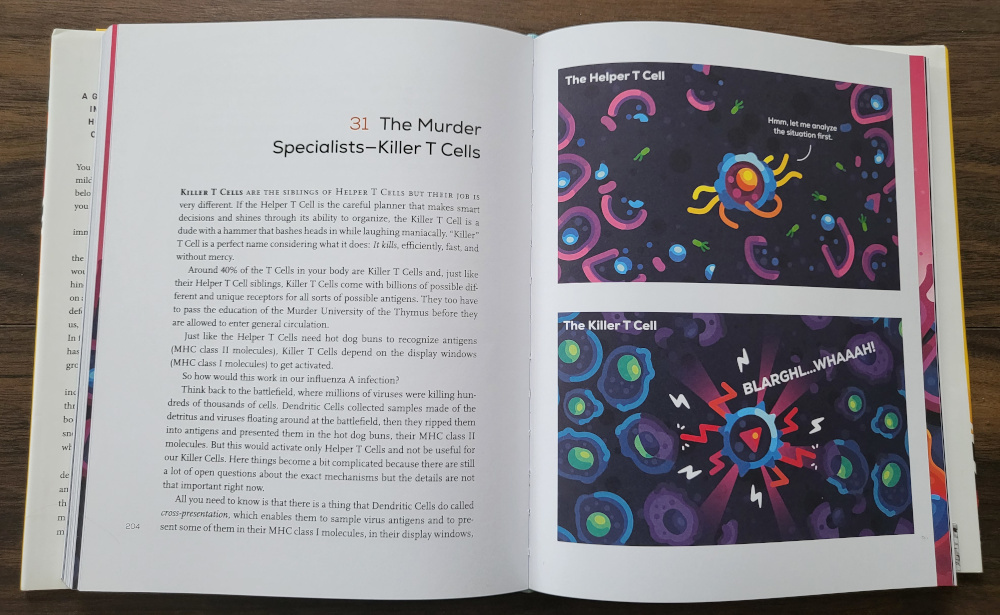

Most illustrations are more understated than the ones shown here, but this is not a book that shies away from depicting a Kiler T Cell saying “BLARGHL”. (Credit: Philipp Dettmer / Random House. Fair use.)

This is not a textbook. Nor is it the kind of pop science writing that tries to make science accessible by giving you lots of biographical detail about scientists. It’s strictly focused on the actual mechanics of the immune system, but written in a style that’s entirely Dettmer’s own. To give a small sample:

The Neutrophil is a bit of a simpler fellow. It exists to fight and to die for the collective. It is the crazy suicidal Spartan warrior of the immune system. Or if you want to stay in the animal kingdom, a chimp on coke with a bad temper and a machine gun. [p. 59]

Of course, Dettmer frequently reminds us that the immune system is not, in fact, sentient or intentional. It’s just that these kinds of analogies are too darn useful to refrain from using them. So, Dettmer talks about hot dog buns, display windows, and desert kingdoms as he helps us navigate the complex nano-scale landscape inside our bodies.

But analogies only go so far, and the book uses biological terms and plenty of straightforward illustrations. At the same time, Dettmer will often (a bit too often) emphasize that he’s still simplifying things greatly. The book is littered with entertaining footnotes that expand on the text.

Cells with two-factor authentication

The immune systems of humans and other animals don’t just have to kill invaders. They have to adapt to viruses they’ve never encountered before, detect cells that have been hijacked, calm down when a threat has been eliminated. To make matters worse, the attackers evolve rapidly!

Immune responses involve the innate immune system, a sort of standing army, and the adaptive immune system, which crafts specialized responses for novel threats. Together, they self-organize into a complex dance. Isolate the threat. Sample data. Ramp up immune responses. Kill or neutralize invaders. Detect cells that behave suspiciously. Mess with virus production.

Perhaps most fascinating is our bodies’ ability to learn and remember—to acquire immunity. At its heart is what Dettmer calls the largest library in the universe: T-cells. Wikipedia has a more understated but no less awe-inspiring description:

Each mature T cell will ultimately contain a unique T-cell receptor that reacts to a random pattern, allowing the immune system to recognize many different types of pathogens. This process is essential in developing immunity to threats that the immune system has not encountered before, since due to random variation there will always be at least one TCR to match any new pathogen.

It takes time for our adaptive immune system to find the perfect match for any given threat. But once it has done so, it switches into a kind of mass-production mode, to produce vast numbers of antibodies tailored to a specific enemy.

To avoid misfiring, cells perform complex verification dances. T-cells undergo a selection process that weeds out ones that might attack the body. And they must be matched with another cell type (B-cells) that have been activated by the same threat. Dettmer calls it a kind of two-factor authentication.

As someone working a lot with technology, I found these comparisons illuminating. Understanding the sophisticated evolved security responses of our bodies may very well inspire us to develop better ways to deal with novel threats of a more digital variety.

Knowledge as immunity

Our brain, in a way, is part of our immune response. Our decisions on what to eat and drink, what to do with our free time, how to prevent and how to treat illness—they profoundly influence our ability to stay healthy, and to get better. When we believe things that are patently false, it can literally kill us.

Dettmer spends the final sections of his book trying to convey how understanding our immune system can help us make better decisions.

He explains the remarkable accomplishment of vaccination as a way to train the body without hurting it: like a dojo where you learn to fight with weapons made of foam and paper. In contrast, parents who opt their kids out of vaccines are sending them to a “Nature Dojo”:

The philosophy of the head trainer is that kids should train with real weapons, real knives and swords, so they are better prepared for the real dangers of the world. After all, it is more natural and real life just is dangerous. From time to time, a student will get a deep cut and require stitches. And yeah, OK, there may be a lost eye and sometimes a kid may die. But it is the natural way! [p. 240]

He asks us to question dubious claims about “boosting your immunity”—reminding us of the immune system’s mind-boggling complexity and interplay of countless parts, where any actually effective intervention can have disastrous effects. He tells us to exercise (it’s obligatory in any book of this kind), and describes how stress can knock our immune system out of balance.

These final sections of the book sometimes get a bit rambling. The most muddled chapter discusses the popular misconception that hygiene has weakened our immunity against disease. Dettmer argues for preserving good hygiene while also embracing the role of nature and dirt in our lives—a reasonable argument that’s unfortunately not very coherently made.

The Verdict

With Immune, Dettmer has managed something very difficult: to write a long book almost entirely about the mind-boggling macromolecular and cellular machinery inside our bodies, without fluff, that’s entertaining to read. I would love to read similar books about subjects like epigenetics, metabolic pathways, or neurobiology!

Science books often have an incongruous approach to visual explanation. Immune is the rare exception—while it does not have as many illustrations as some readers might expect from the Kurzgesagt founder, what’s here supports the text perfectly in a consistent, pleasing style.

The latter parts of the book would have benefited from a bit more rigorous editing, but I’m glad that Dettmer’s funny and casual voice hasn’t been whittled down to science-journalism-speak.

All in all, I cannot recommend the book highly enough, and would give it a full 5 stars.

I love a good romantic tale, even of the overwrought variety (I am a The Notebook enjoyer). Therefore I was happy to give Big Dipper a try, which is a short, kinetic (choice-free) visual novel about a romantic encounter on New Year’s Eve. In case you’re wondering, it’s all very chaste stuff; the title is no naughty double entendre.

Developed by Team Zimno from Russia [*], the story is told from the perspective of Andrew, a somewhat sullen young man who encounters his manic pixie dream girl when a woman named Julia literally sleepwalks into his life and his cabin.

The game throws in a bit of the supernatural, but it’s over after less than two hours, so it doesn’t really go very far with any of it. That’s a shame, because earnestly incorporating Slavic folk tales could have made things a lot more interesting!

The relationship between Andrew and Julia develops implausibly. They grow closer through sharing stories of loss of alienation with each other, but the romance is otherwise just rushed along a “they dislike each other → they love each other beyond measure” path without ever building genuine momentum.

We’re only in the first scene, and there are already typos like “busrt” instead of “burst”. (Credit: Team Zimno. Fair use.)

Big Dipper certainly gets the aesthetics right. Made with Unity, the game looks better than your average visual novel, with nice animations for the snowfall outside and the cozy fireplace inside. The character art and full-screen graphics also look good, and are enriched with chibi-style pictures during key scenes.

Unfortunately, it’s hard to overlook the shortcomings. Aside from a rushed story that doesn’t withstand the slightest scrutiny, it’s difficult to justify the lack of attention to detail in the writing. You’ll notice the first typos and misspellings just a few paragraphs in, and we’re talking about glaring ones (“busrt” instead of “burst”, “cheked” instead of “checked”) that could have been caught with any spell checking tool.

Big Dipper is only $5, but you’ll find much better romantic visual novels even for free. Unless you’re desperately looking for a winter-themed pick-me-up and are willing to look past its issues, you can safely skip it.

[*] It’s worth noting that the authors have publicly spoken out against Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and against Vladimir Putin.

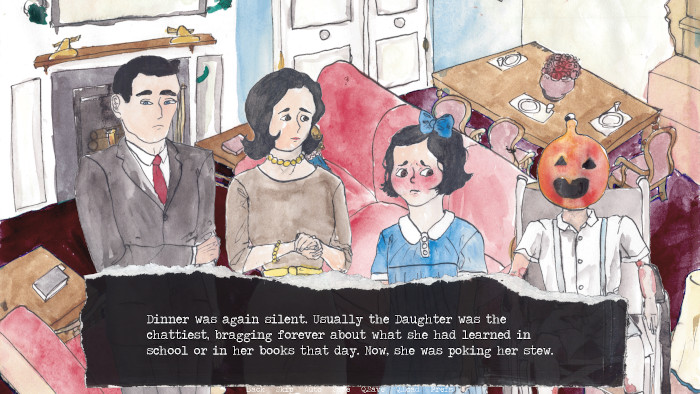

Pumpkin Eater is a kinetic visual novel, which means that it’s a story with art and sound, but with no player choices. The $2 regular sales price suggests a short story, and indeed I finished it in about 30 minutes.

Given how short it is, I don’t want to give too much away. In a nutshell, it’s about a family who loses a child in an accident but cannot let go. What follows is a tale of decay and insanity, told in (the authors assert) a medically accurate manner.

The characters and backgrounds are lovingly painted in watercolor, which creates a contrast with the story’s morbid content. (Credit: thugzilladev. Fair use.)

I appreciate attempts to demystify death, even if it’s done in the form of a horror story. Ultimately, that seems to the point of the game, which comes complete with a glossary.

The story is engaging, and it uses music and sound effects well. It won’t scare your pants off, but it might make you lose your appetite. It is also likely to stay with you. 3.5 stars, rounded up.

When governments, corporations and other organizations act unethically or illegally, only people on the inside may know about it. If they choose to tell someone who might bring about change, they become whistleblowers.

Published in 2001, C. Fred Alford’s Whistleblowers: Broken Lives and Organizational Power examines the personal sacrifice it takes to oppose an organization’s actions. From interviews and a review of prior research, Alford concludes that in spite of many legislative attempts to protect whistleblowers, retaliation is the norm, not the exception.

How organizations fight back

Whistleblowers are often not fired immediately. They are moved to “offices” that previously served as closets; their responsibilities are curtailed; their performance is put under a microscope. Only after sufficient time has passed to create distance to the act of whistleblowing, they are fired, frequently for “poor performance”.

After losing their job, they may find it impossible to work in their chosen sector again, thanks to informal blacklists. Whistleblowers are portrayed as “nuts and sluts”, their sanity and character called into question. As Alford puts it, the process is complete “when a fifty-five-year-old engineer delivers pizza to pay the rent on a two-room walkup.”

Considering this characterization, one might expect Alford to support whistleblower anonymity. Not so—anonymity, he claims, is a road to nowhere (p. 36):

Anonymous whistleblowing happens when ethical discourse becomes impossible, when acting ethically is tantamount to becoming a scapegoat. It is an instrumental solution to a discursive problem, the problem of not being able to talk about what we are doing. Whistleblowing without whistleblowers is not a future we should aspire to, any more than individuality without individuals or citizenship without citizens. If everyone has to hide in order to say anything of ethical consequence (as opposed to “mere” political opinion), then we will all end our days as drivers on a vast freeway: darkened windshields, darkened license plate holders, dark glasses, speeding aggressively to God knows where.

Personally, I think an “instrumental solution to a discursive problem” is still a fine solution, especially if it happens to save lives or serve the public interest. Much as Alford agonizes about the sacrifices whistleblowers make, he seems unwilling to imagine a world in which those sacrifices can be lessened.

Psychoanalysis to the rescue

Because many of the people Alford spoke with attended self-help groups (which selects for trauma), and because his book rarely deals in numbers, it’s difficult to say how statistically valid his observations are. Much of the book is focused on psychoanalysis: What causes whistleblowers to act, and how do they process the consequences of their actions?

Alford theorizes that whistleblowers are motivated by what he describes as “narcissism moralized”. To put it another way, whistleblowers can tolerate the alienation from everyone else more than they can tolerate being in conflict with their idealized moral self.

It’s a reasonable argument, considering that whistleblowers often act alone—so their impulse to act is often likely the result of an inner conflict. But when he characterizes whistleblowers’ motives and feelings, Alford readily dismisses evidence that isn’t consistent with his own views.

In describing one case, he writes: “Ted protests too much. For that reason I distrust his account” (p. 39). This kind of reasoning makes me worried that the author may be an unreliable narrator of whistleblower motivations, and I would rather read more quotes and fewer abstract characterizations.

How many whistleblowers discuss their actions with loved ones beforehand? How many are deeply appalled by imagining the consequences of the organization’s actions on the outside world? What Alford offers us are generalizations, made more tedious with frequent repetition and verbosity, for example, when he writes about the state of “thoughtlessness” (p. 121):

Thoughtlessness stems not merely, or even primarily, from fear. Thoughtlessness arises when we are unable to explain our fears—that is, make them meaningful, comprehensible, knowable. This happens when we lack the categories to bring our fears into being. Common narrative is, I’ve argued, of little help in this regard.

Social theory could be more helpful than it is. Liberal democratic theory assumes that politics is where the action is, and so it assumes that individualism is possible. Foucault’s account assumes that individuals don’t exist. Neither approach gets close enough to life in the organization, to say nothing of the lives of those who suffer the organization, to help individuals make sense of the forces arrayed against them.

If you enjoy the kind of analysis that says in 100 words what could be said in 10, you’ll find plenty of it here.

The Verdict

In fairness, Whistleblowers is a short book (170 pages including the index), and it does tell some interesting stories about different types of whistleblowers in different fields, from engineering to accounting.

It offers some metaphors which I’ll almost certainly find myself using again—for example, it describes life after whistleblowing as akin to space-walking, because many whistleblowers have learned the hard way that the world doesn’t work the way they thought it did.

The most useful takeaway from Alford’s book is a deeper understanding of the often very heavy cost of whistleblowing. Alford ultimately characterizes it as a “sacred” act; I would compare it perhaps with blasphemy. To understand the cost of telling the truth should prepare us to lessen it.

Cyberpunk stories often take place on Earth in a dystopian future characterized by a) darkness, rain and neon lights, b) corporations running everything. So, really, mostly a darker, rainier version of the present.

Synergia, a visual novel by indie developer Radi Art, takes place on a desert planet colonized by humans that is home to multiple political factions, including a dominant superpower, the Empire.

In other respects, it follows the cyberpunk template, featuring cityscapes drenched in neon lights; cyborgs, androids, and evil corporations. It also takes itself quite seriously.

This is a mostly kinetic visual novel, meaning that there are only a few choices (three in total) you get to make to influence the course of the 4-5 hour long story.

The story revolves around Escila, or Cila for short, a cop demoted under circumstances that will be revealed later in the story. When looking to replace her household android, she gets more than she bargained for: an outgoing, cheerful and remarkably human-like android named Mara. Cila soon becomes entangled in a web of conspiracy and romance.

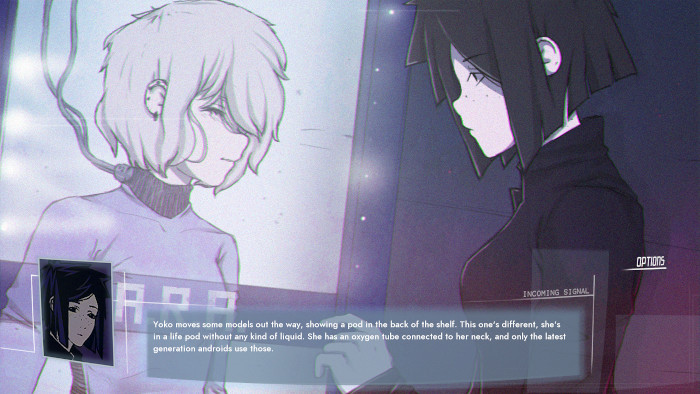

Some of the full-screen art is quite well-done. Here, Cila encounters the android Mara for the first time. (Credit: Radi Art. Fair use.)

Romance without chemistry

Synergia is at its heart about the relationship between Cila and Mara. Unfortunately, as a romance story, Synergia failed to click for me. It reads as a relationship of necessity and convenience—two people drawn together only out of alienation towards the rest of the world, and out of sheer loneliness.

The larger narrative of a conspiracy involving androids, rebels, and corporations is convoluted and unsatisfying. Dialogue doesn’t read like the interaction between different people, but like a single writer cramming exposition into speech bubbles. It doesn’t help that the UI doesn’t always make it obvious who’s talking.

The writing suffers from a few typos and grammar errors. The character art and backgrounds are original and maintain a coherent style. As is typical for low budget visual novels, a few backgrounds are overused. The game’s strongest point is its soundtrack, which never dominates but creates suitable ambience.

I can’t recommend Synergia, but your mileage may vary. If you love the cyberpunk aesthetic and enjoy romance stories that are on the more mechanical side, you may get something out of it.

Slay the Spire is not the first roguelike deck-building game, but its massive success created a recipe many indie developers would soon try to follow.

The game doesn’t owe its popularity to its rich lore. You’re ascending a tower—excuse me, spire—fighting monsters on its many floors, to face a final enemy: a corrupted, beating heart. Random events hint at a larger mythology, but if you’re looking for a narrative adventure, look elsewhere.

The monster bestiary is also not what will keep you playing this game. While the art and animation are always serviceable, the array of cloaked figures, slimes, geometric shapes, and bands of thieves and gremlins gets a bit samey after a while.

What sets Slay the Spire apart is the tightness of the card-based battle mechanics, the unique play styles of the different characters, and the clever combination of cards and relics to make each run feel different.

Chance and strategy

You first play as the “Ironclad”, a powerful masked warrior. You navigate the spire across a path of your choice: you can face challenging encounters with large rewards, pursue random events, or plot the safest course to the level boss.

Monsters on the map indicate turn-based battles against one or multiple opponents. You draw cards from your deck in random order, and expend limited energy to play some of them. (Your opponents don’t have cards.)

The game will usually tell you what the enemy will do next: attack, defend, inflict status effects, and so on. This gives you a chance to prepare: if the enemy is about to do a lot of damage, you better have those defenses ready.

After each battle, you pick up new cards and other loot. As you ascend the spire, you’ll also find treasure chests and shops. Question marks on the map lead to random events. Those may have small negative or positive consequences, or give you dramatic choices: Would you like to play the rest of the game as a vampire?

The Silent, one of the four playable characters, faces a Shelled Parasite. It will take carefully planned moves to penetrate the monster’s plated armor while minimizing inbound damage. (Credit: MegaCrit. Fair use.)

Game-changers

Among the items you can find are relics. These can significantly alter the game mechanics—for example, you might get extra energy every three turns, or boost the effectiveness of certain cards.

More and more content gets unlocked the longer you play—additional characters (four in total), cards, and relics. That means that a relic you unlock after 20 hours of play could be transformative for your next run.

The four characters offer fundamentally different play styles: The Silent is a rogue whose cumulative poison attacks can bring down the most powerful foe. The Defects is a sentient automaton who uses orbiting energy orbs to line up deadly chain reactions. The Watcher is a blind ascetic who uses “stances” to collect her energy and defenses (“calm”), then attack with twice the strength and vulnerability at the right moment (“wrath”).

Learning by dying

Battles can feel terribly unfair—such is the nature of roguelikes—but there’s enough strategic depth to reward repeated play. You will get better, learn to avoid unnecessary risks, and achieve easy defeats in battles that seemed unwinnable before.

To keep you playing, the game never ceases to throw new challenges your way, and that’s without taking into account lovingly created mods like Downfall, a fan expansion that lets you play as the bosses.

After 40 hours of play, having faced (but not defeated) the game’s ultimate boss and unlocked most cards and items, I’ve decided to put Slay the Spire down again for now. But I know it’s sitting in my library, ready to give that dopamine rush that only a perfectly executed game can.

If you like the genre, I also recommend Krumit’s Tale (review), Iris and the Giant (review), and Dicey Dungeons (review). All were released after Slay the Spire, and each brings something new to the genre.

The main focus of Hardcore Gaming 101’s “Retro Indie Games” book series are games that look, feel and/or play like old-school games from the 1980s and 1990s, but that are much more recent indie titles. (See my review of the first volume.)

The second volume covers both old titles that didn’t make the cut last time (e.g., Papers, Please! and Fez), and very recent games like Helltaker, Paradise Killer and Lair of the Clockwork God.

The format is largely the same as before: each game is richly illustrated and described in detail, with heavy focus on gameplay and story, and little emphasis on any other aspect such as the developers or how the game was made. As before, games are grouped by developer.

With 67 individual games, every reader with any appreciation for indie games is likely to discover at least one or two to add to their backlog. For me, that included Katana Zero (the time manipulation mechanic sounds super-interesting) and The Binding of Isaac (it just seems like a wild ride).

As with the first volume, I still feel the series could do better at being an actual guide to genres and developers. As an effort to catalog and describe some of the greatest retro-styled indie titles of the last decade or so, it is without equal.

The full list of games in the second volume follows (grouped by developer):

Cuphead

Celeste

Panzer Paladin

The Messenger

Cyber Shadow

Gunpoint

Aces Wild

Blazing Chrome

Katana Zero

Minit

Fight ‘n Rage

198X

Cave Story

Kero Blaster

La-Mulana (series)

Xeodrifter

Hollow Knight

Blasphemous

Iconoclasts

Dex

Rabi-Ribi

Pharaoh Rebirth

Touhou Luna Nights

Record of Lodoss War: Deedlit in Wonder Labyrinth

Fez

The Binding of Isaac

Dusk

Project Warlock

AMID EVIL

Cruelty Squad

Saturday Morning RPG

Cosmic Star Heroine

Anodyne

Anodyne 2: Return to Dust

Into the Breach

Chroma Squad

Katawa Shoujo

Digital: A Love Story

Don’t take it personally babe, it’s just not your story

Analogue: A Hate Story/Hate Plus

Ladykiller in a Bind

Broken Reality

Coffee Talk

Unavowed

Lamplight City

The Low Road

Ben There, Dan That!

Time Gentlemen, Please!

Lair of the Clockwork God

Paradise Killer

Return of the Obra Dinn

Umurangi Generation

Hypnospace Outlaw

Oxenfree

Back in 1995

Stories Untold

The Count Lucanor

Yuppie Psycho

Detention

Devotion

Paratopic

Anatomy

Papers, Please

Stardew Valley

Helltaker

As a twelve-year-old, Gwendy Peterson met a stranger who gave her a magical box that can destroy the world. That’s the premise of the Gwendy trilogy by Stephen King and Richard Chizmar.

The first book, Gwendy’s Button Box (review), was a fine story that stood on its own as a morality tale. The titular button box can fulfill wishes and wreak destruction—including at the planetary scale. As child custodian of the box, Gwendy used some of its powers, but was never corrupted by them.

In the mediocre sequel, Gwendy’s Magic Feather (review), Gwendy became a celebrated author and elected Congresswoman, and the box once more played an (ultimately anticlimactic) role in her life.

In Gwendy’s Final Task, the mysterious man or being who originally gave her the box tasks her to get rid of it once and for all. Because it’s a magical box, throwing it into a volcano won’t do. It must be…shot into space!

And so it is that Gwendy, now a Senator, finds herself on the way to a space station, with the button box locked away in a steel box marked “CLASSIFIED MATERIAL”. The spaceflight is organized by a SpaceX-style private company that is hoping to monetize space tourism.

That explains why one of the other passengers on board is an obnoxious billionaire. It doesn’t explain why the man seems to be completely obsessed by what’s in the steel box. Meanwhile, Gwendy is literally losing her mind to early onset Alzheimer’s disease.

The setup is ridiculous, but it mostly works. The enclosed environment, combined with Gwendy’s dwindling mental faculties, builds suspense. King rewards his constant readers with plenty of references to other works, including the Dark Tower series many consider his magnum opus.

The ending leaves no doubt that this truly is the final book in the series. That’s probably for the best. If you’ve made it to the second book, the conclusion is definitely an improvement, and I would recommend picking it up. If you’ve not started the trilogy yet, there are much better works in King’s oeuvre.

In the late 19th century, as the United States fully consolidated itself and its territory (through war and ethnic cleansing), its elites began to realize openly imperial ambitions. These ambitions reached a fever pitch in the Spanish-American War, which led to the US establishing control over Puerto Rico, the Philippines, Guam, and (nominally independent) Cuba.

When Smedley Butler, the son of an influential Pennsylvania family, joined the US Marines in 1898, he was caught up in the war fever of the time. But instead of fighting the Spanish, he soon found himself helping to police America’s empire on behalf of its most powerful economic interests.

Decades later, Butler, now a Major General, started to write his own script. In 1933, he alleged that he was invited to take part in a conspiracy among wealthy businessmen to overthrow U.S. President Roosevelt and install a dictator.

It became known as the Business Plot. A congressional committee concluded that “there is no question that these attempts were discussed, were planned, and might have been placed in execution when and if the financial backers deemed it expedient." Nobody was prosecuted.

In his final years, an increasingly radical Butler gave fiery speeches and penned a short book called War is a Racket. It contains the following passage:

I helped make Mexico, especially Tampico, safe for American oil interests in 1914. I helped make Haiti and Cuba a decent place for the National City Bank boys to collect revenues in. I helped in the raping of half a dozen Central American republics for the benefits of Wall Street.

Late in his life, Butler denounced war and empire, and fought for veterans’ rights. (Credit: Bettman/Getty Images. Fair use.)

Legacies of Empire

For American journalist Jonathan Katz, Butler’s life presents a lens through which to view the history of American imperialism, and its modern legacies. In Gangster of Capitalism, Katz traces Butler’s career in the military and his stint as Philadelphia’s “Director of Public Safety”, a role in which he waged a brutal war on crime in the city.

Katz makes it clear that Butler, in spite of his Quaker upbringing, committed truly horrific and violent actions, and often rationalized them through the pervasive racism of the time. As part of the nearly 20-year-long occupation of Haiti by the United States, Butler instituted de facto slavery to build up the country’s infrastructure.

Unlike the opaque Business Plot, the corporate interests that profited from these endeavors and drove US policies are well-documented, from bankers to landowners to oil companies. Franklin Roosevelt himself pursued personal agriculture investments in Haiti while helping direct its occupation as Assistant Secretary of the Navy.

In each chapter, Katz describes the modern legacy of American imperialism, including by quoting Haitians, Filipinos, Chinese, and others he has met. While Americans have forgotten the little they have ever known of this history, the citizens of these countries have not. Katz’s travelogue enriches the book and makes this history tangible.

Past and Prologue

Gangsters of Capitalism is an accessible, informative and engaging book. At no point does Katz turn from facts to polemic. He gives clear-eyed accounts of the brutal regime of Nicaragua’s leftist autocrat Daniel Ortega, and the imperialist ideology of China under Xi Jinping. The book is a critique of empire, not an anti-American screed.

It is also a timely book, as another imperialist power, Russia, wages a war of aggression against neighboring Ukraine. What role should Western powers play today to counter such naked brutality? Can military alliances like NATO protect the peace in the 21st century? What alternatives are there?

The invasion of Ukraine marks a new chapter in world history, and we all benefit from remembering previous chapters—including America’s own brutal imperial history—to navigate the moral landscape now before us.