Review: Final Fantasy VII Remake

In a dystopian and industrialised world, the Shinra Electric Power Company rules over the city of Midgar in all its facets.

The company exploits a natural resource called Mako for energy generation at great environmental cost.

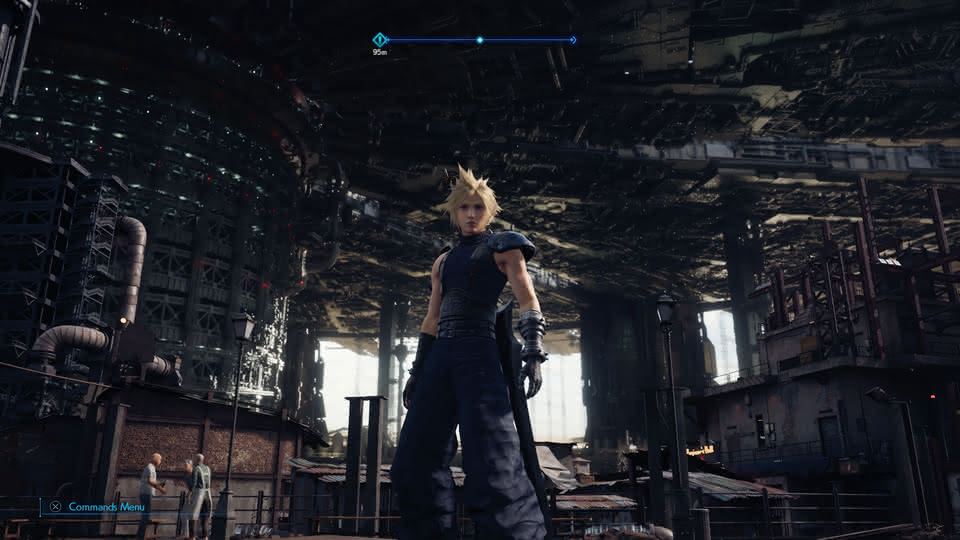

The game starts with you in the shoes of Avalanche, a small group of eco-terrorists on a mission to destroy one of Shinra’s Mako reactors.

Throughout the game, Avalanche’s conflict with Shinra escalates further as they retaliate and the group’s members grow closer together. But something isn’t quite right…

Final Fantasy VII Remake, as the title suggests, is the remake of the 1997 gaming classic Final Fantasy VII by Square.

Remaking a famous game like that comes with a lot of pressure to live up to the beloved original but also creative opportunities.

Firstly, you have an established foundation to build on with decades of hindsight regarding what did and didn’t work at the time.

And secondly, a lot of players will be somewhat familiar with the original.

This familiarity allows for a unique dialogue with the audience—what you decide to keep and what you decide to change.

Within the context of a remake, these aren’t merely choices but active communication. And FFVII Remake, as it turns out, is very talkative.

The nature of the remake

First, to dispel some potential confusion, this is not a complete remake of FFVII as the name might imply. It is, instead, the first entry in a recently announced trilogy. In the original game, eventually, you get to explore the world outside of the city, but that’s all you will see in this remake.

Obviously, stretching FFVII like this is the result of corporate demand. They weren’t just going to remake a cultural titan like Final Fantasy VII and call it a day. And while the profit-driven endeavours of big publishers like Square Enix grow more shameless by the year, I can’t deny that I am fascinated by what developers manage to do creatively with these business-mediated constraints. Suffice it to say, I think they succeeded in creating something quite special here.

In one way, it’s exactly what you would expect from a remake like this, but in another, it completely defies those expectations. Even more impressive is that the game walks this tightrope of seeming contradictions very well.

As far as the gameplay is concerned, FFVII Remake gets the action RPG treatment. These changes bring it in line with other contemporary Final Fantasy releases like FFXV. And when it comes to the adaption of the story for the remake, things are simultaneously similar and different. Certain things and scenes are adapted very faithfully. For example, the famous introduction to the original is adapted beat by beat. But it doesn’t take long for you to notice major structural differences between the two games. In this review I will mainly focus on the differences and how most of them enhance the original.

Extended world and characters

The general throughline with JRPGs hasn’t changed much since 1997. There is a greater focus on action for the gameplay now, but as far as it goes with the story, characters, and world-building, things are virtually the same. We have a linear spectacle-driven narrative with a diverse cast and a greatly fleshed-out world. With this remake taking the first quarter of FFVII and fleshing it out to about 35 hours, it has room to explore these narrative elements in a depth the original never could. Most immediately apparent is this in the characters. Every single one of them has something new going for them. From small things, like Barrett, the charismatic leader of Avalanche being afraid of heights, over Tifa, another Avalanche member, having frequent doubts about the group’s whole terrorism thing, to major character changes. The most prominent example of such character changes is Jessie. In the original, she is a relatively minor character, but now she is treated with the same attention as major playable ones. She gets much more screen time and further an extended backstory into how her father’s work for Shinra radicalised her into joining Avalanche.

I also should not dismiss what modern hardware capabilities brought to the table. In the original, the 3D models for characters were rough approximations of human anatomy, stiffly animated, where individual polygons were visible. Now, three console generations later, we get richly detailed characters, that smoothly move through their scenes and the world. The new voice acting breathes in the final bit of life into these characters. It gives the game a whole new overall feeling.

Not only do the enhanced visuals sell the characters much better, but also the world as a whole. The best example of this is the city itself. The population of Midgar is greatly divided by class, which was already made clear in the original by having two levels to the city The upper level is built on plates arranged in a circular shape, suspended in the air. Here industry and commerce are situated, including the Mako reactors and Shinra’s headquarters. Most Shinra employees appear to be living here.

The lower classes of Midgar society live in slums on the ground below the plates. So the lower classes are constantly reminded of their social standing with this subtle visual metaphor. In the original though, this wasn’t always that apparent with its fixed top-down camera angles. Now, with the third-person camera following your character, you can look up all the time. It might sound small, but this constant reminder about Midgar’s class divide adds so much to the overall experience.

Looking up from the slums (Credit: Square Enix. Fair use.)

But this remake also finds entirely new ways to comment on the hyper-capitalist nature of Midgar. If you are familiar with Final Fantasy, you will know about Potions. They are a family of generic healing items that have been with the series since the beginning. In FFVII Remake, instead, Potions are produced by a huge corporation. And naturally, the game world is littered with advertising and vending machines for Potions. This repurposing of familiar core elements of the series for thematic ends is genius. Again, it might seem small, but it adds so much to the overall character of the world.

(Credit: Square Enix. Fair use.)

Dealing with FFVII’s narrative legacy

The remake largely follows the events of the original. But the way the game does this is anything but typical. If you are familiar with the original story, you will quickly notice small divergences. For example, the remake introduces the primary antagonist Sephiroth right after the beginning, whereas, originally, that would be a few hours away from that point. These small changes in compound foreshadow much more large-scale changes in the story, but when that fork in the road is reached, something strange happens.

There are forces at work to push back from the story changing too much. When a major divergence in the story is about to happen, ghostly figures called Whispers breach onto the scene and prevent the change from happening. They block the hero’s path or remove characters from the scene before some revelatory backstory could be delivered too early. The Whispers forcefully bring this remake’s story into accord with the original.

What exactly the Whispers represent isn’t clear, but they appear to be the writers’ literal manifestation of anxiety over making changes to the story of a game as beloved as Final Fantasy VII. Anxiety over done changes not being as good as they thought, or, sadly more likely, anxiety over backlash from fans for any changes having been made at all. It asks interesting questions about the nature of remakes. Should developers merely modernise the old and keep with the original’s spirit, or are massive changes—a completely different game even—okay?

In the video game space, we have many faithful remakes. And even in this game, it seems like the Whispers are winning with another modernised but structurally untouched game. But at the climax, our protagonists challenge fate itself and come out victorious. As our heroes prepare to leave Midgar, the game breaks the fourth wall letting us know that the story for this remake’s sequel is yet untold. Thus with the end of the game, we reach the long foreshadowed fork in the road, and the game goes full speed into the unexpected. What an incredible statement!

Avalanche’s revolution

Despite Final Fantasy VII Remake refraining from making major structural changes to the original’s story until the finale, the changes up until that point can’t exactly be called minor. The most noticeable changes lie with the overall politics of the game, and thus with the terrorist group at the heart of the narrative: Avalanche.

There are two important differences in how the remake approaches the group. The first is in how the game frames Avalanche’s actions, and the second is in what Avalanche does. The reframing has two goals: making the group’s antagonism against Shinra more realistic and painting the group as more sympathetic.

Firstly, Avalanche is part of a wider resistance network now. In hindsight, it was a bit weird with a mega-corporation sucking the life essence from the planet that only a handful of radicals chose to take action against it in the original. This change makes their struggle much more believable.

Another such change that reframes the actions of the group is the bombing mission in the intro. In the original, blowing up the Mako reactor causes a chain reaction that destroys the reactor and its immediate neighbourhood. Contrast that with the remake, where they only plan for a small and controlled explosion to take out the reactor core. But when Shinra’s president gets wind of the plan, he gives the order to destroy the reactor from the inside, which triggers a chain reaction all the same. The company blames the resulting destruction on Avalanche.

At the end of the mission, the game makes you walk through the destroyed streets of Midgar with injured people and onlookers everywhere. While Jessie theorises about what she might have done wrong to trigger the greater explosion, you the player, know that Shinra is to blame. This reframing makes Avalanche immediately more sympathetic to newcomers. It would be much harder to empathise with them just blowing up a reactor in the knowledge that innocent people would die, regardless of their motivation. It also nicely foreshadows the much worse things Shinra will do later.

But not everyone is willing to go as far as Avalanche or even thinks the status quo is bad. When the team arrives in the slums after the bombing mission, a man is tearing down pro-Avalanche posters. He makes it clear that he thinks what Shinra is doing in Midgar is progress. He looks up at the steel plates and sees progress, not oppression. It makes a lot of sense. Shinra couldn’t do what they do without many willing participants. Does that remind you of something?

It is clear that the much increased awareness of the ensuing climate catastrophe is the reason for this remake’s increased radicalness. Not only has the environmentalist message of the original FFVII not aged a bit, but it was updated to be allegorically about climate change. Because of this, the parallels are so stark. And it also allows FFVIIR to delve into a lot more adjacent topics in a seamless manner. The game explores how corporate media manufactures public opinion that is beneficial to the powerful. It explores how despite Shinra being a gigantic threat to the planet, many people choose to be complicit.

But even more interestingly, the game shows how radical revolutionary groups can structure themselves.

When looking at revolutionary struggle, it is easy to overemphasise the big event. In the case of FFVIIR, that would be destroying Mako reactors. But it is arguably much more important to aid in the creation of a revolutionary society that can facilitate the fought for change. This game makes this clear by focusing on community building between the big story moments. You do this by helping the people in the slums in their daily struggles. And as a bonus, it nicely slots into the familiar side questing structure of most JRPGs.

Later, when Shinra unleashes horrifying death and destruction upon the slums in revenge against Avalanche, you are the one organising an evacuation from there, managing to save a lot of lives.

The general handling of this event is curious in comparison to the original. Not only does no such evacuation take place there, but also later, this event is used as the catalyst for Barret to regret his radical actions. He accepts the responsibility for what happened because Shinra was reacting to Avalanche−violence begets violence, that’s the moral of the story. This remake rejects this both-sidesism, giving us an energetic and angry Barret, who blames Shinra completely for what they have done. This change greatly elevates the story because this acceptance of personal guilt severely undercuts core messages of the original and trades it with an unsatisfactory conclusion.

It might sound somewhat contradictory, but this remake is simultaneously broader and more focused than its predecessor in its political messaging. It’s also a lot more angry and empathetic. I love it.

Action Time Battle

The gameplay is quite similar to the story. In many ways, the remake builds on and pays tribute to the original. This manifests in small parts in the few mini-games across the game, getting a modern do-over and polish, or even introducing new ones. But when it comes to gameplay, most people will think of the combat.

The remake attempts a fusion of the original FFVII’s combat and the combat of the most recent series entry, Final Fantasy XV.

In this fused combat system, you have over-the-shoulder control of a character, triggering combat actions on button presses. However, in contrast to XV, you can switch between characters on the fly. If there are enemies high up in the air, and they become inconvenient to reach with Cloud because he is a sword fighter, you could switch to Barret, who has a rotary cannon for a hand.

Another distinguishing factor from FFXV is the menuing. When you open the menu during combat, time slows down, and you have the space to deliberate your next move in this otherwise quite hectic combat system. From the menu, you can use items, abilities, and magic spells—the expected—but also issue all those same commands to characters you don’t control. And this is where the tactical aspects of FFVII’s combat system come into play. Overall this fusion works very well.

Since you can take active control over characters, the way combat roles work shifted. Instead of characters having somewhat predetermined roles in combat—healer, damage-dealer, and so on—every character is a good base fighter who is fun to control. For example, Aerith, another character that joins your party, got originally funnelled quite heavily to be a healer or a spell caster because her physical capabilities are terrible. In the remake, she is a competent base fighter from the get-go, very useful, as her attacks are ranged and very fun to control.

Characters now entirely specialise through Materia, which go into the designated slots of your character’s equipment. Materia can give a character either passive abilities or spells to cast. This is great because it allows you to pursue your dream party of characters. What is also fantastic about this is that when integral party members are taken away from you for story reasons, with a bit of Materia juggling in the equipment menu, you can restore the missing character’s functionality for your party. However, since that substitute characters likely won’t have the same sum of Materia slots across their equipment, it also encourages experimentation. If you have to make do with less, what do you really need? If you have more, what Materia do you want to try out?

Another novelty that encourages experimentation is the many different weapons the characters can equip. Many of them feel very different, as each one comes with a unique ability. The twist is that each weapon gives you a sort of combat mini-quest to attain mastery over the weapon. Such mastery allows you to keep the ability even when equipped with a different weapon. This has two benefits. For one, the given mini-quest can guide you in using the weapon effectively because the tasks always require you to do the weapon’s unique thing. And secondly—as mentioned before— it encourages experimentation. It is a common problem in RPGs that you effectively get locked into a character build simply because you have used that build for a while, levelled up all your equipment and so on. However, when you eventually find something new that you would like to try, you would have to start from zero all over again. This discourages experimentation over the course of a game because so much about your character is effectively set in stone. The more you go on the less likely you are to switch things up. Final Fantasy VII Remake cleverly avoids this problem.

However, the one major issue I have with this new combat system is that the damage that you receive in battle stays when it is over. Now, this is of course how it was in the original, but since so many things were changed about the combat system for this remake, being conservative here has negative consequences.

Having to heal after many encounters so that you are prepared for the next one slows down the game. While this was passable in the original since the combat system was also passive, in the remake, once the engaging action is over, things grind to a halt as you have to navigate menus to your healing items and spells. And unlike using the menu in combat, the strategic component is absent. It’s just tedious. And it gets more and more tedious as the game goes on because with time your inventory holds many low potency healing items, which are of little use in combat beyond a certain point. So if you want to be efficient, you use these items outside of combat, making the regular healing ritual even slower.

It seems like the developers noticed this as well because, towards the end, you will increasingly see more benches in the areas you explore. These are for fully healing your party for free. It does soften the impact of this issue but much too late and too little. So while the devs took precautions for the healing ritual not to escalate too much, it’s still annoying.

Conclusion

Final Fantasy VII Remake is everything a Remake should be and goes even beyond that. It greatly extends a gaming classic thematically, narratively, politically and gameplay-wise. It is self-aware of the cultural impact of the original game, but it is also not afraid of bold divergences, especially at the end.

The fusion the remake provides of Final Fantasy XV’s combat system and Final Fantasy VII’s traditional Action Time Battle is largely a success. But the unfitting health-management approach does dampen the action quite a bit.

Overall, this is brilliant, and whatever the follow-up to this remake will be, I’ll be eagerly awaiting it.

9/10