A cross of thorns

-

openlibrary.org/works/OL20005050W

Online stores IndieBound Amazon - Elias Castillo

-

yokut-1592612013327.jpg

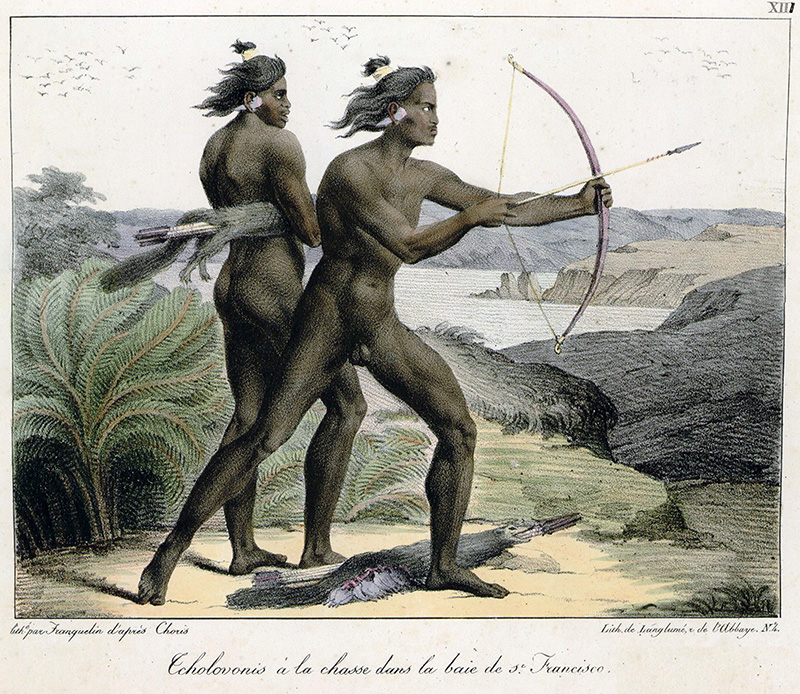

Yokuts hunting near San Francisco Bay as depicted by Russian artist Ludwig Chloris.Credit: Ludwig Chloris. CC-0 or public domain.Source data licensing:

Data from OpenLibrary is in the public domain.

lib.reviews is only a small part of a larger free culture movement. We are deeply grateful to all who contribute to this movement.Reviews

Please sign in or register to add your own review.

Missions of deathI lived in the San Francisco Bay Area from 2008 to 2015. One name that you’ll encounter sooner or later in this region of the United States is Junípero Serra: from Junipero Serra Freeway to Junipero Serra Boulevard, from schools to playgrounds, from hiking trails to the highest mountain peak in Monterey County, and of course the statues—so many statues.

Canonized as a saint in 2015, Serra was an 18th century priest and friar who founded the first Spanish missions in California. Pope Francis claimed that Serra “sought to defend the dignity of the native community, to protect it from those who had mistreated and abused it.” The missions Serra started are popular tourist attractions.

In 2004, Elias Castillo (1939-2020), a journalist and three-time Pulitzer Prize nominee, wrote an op-ed titled “The dark, terrible secret of California’s missions” that described Serra’s work in starkly different terms:

[L]ocked within the missions is a terrible truth—that they were little more than concentration camps where California’s Indians were beaten, whipped, maimed, burned, tortured and virtually exterminated by the friars.

The op-ed was well-received by others familiar with this history, and was read into the Congressional Record. This inspired Castillo to write the book A Cross of Thorns: The Enslavement of California’s Indians by the Spanish Missions (2015).

Castillo documents that Serra was a reactionary even by 18th century standards, a man who believed in witches, rejected Copernicus, practiced extreme self-flagellation, and regarded the natives of California as savages who had to be enslaved to be brought to salvation.

Yokuts hunting near San Francisco Bay as depicted by Russian artist Ludwig Chloris. (Public domain)Fever dreams of salvation

Natives were herded into the missions and were forcibly returned there if they tried to flee. They lived in conditions of forced labour, and died by the thousands, often from disease which ran rampant due to the high population density. Far from “protecting” the natives, Serra resisted efforts to reduce the rate of death, to provide education or better care.

Instead of education, there was daily mass in Latin, which the natives did not understand. The Church enforced its sexual morality, separated men from women, and punished expressions of intense emotion, including grief. In a 1780 letter to Felipe de Neve, then governor of the Californias, Serra justified the use of flogging:

“That spiritual fathers should punish their sons, the Indians, with blows appears to be as old as the conquest of these kingdoms [the Americas]; so general in fact that the saints do not seem to be any exception to the rule. In the life of Saint Francis Solano … we read that, while he had a special gift from God to soften the ferocity of the most barbarous by the sweetness of his presence and words, nevertheless … when they failed to carry out his orders, he gave directions for his Indians to be whipped.”

Castillo’s book is unsparing but rigorous and well-sourced, often in the words of the people who committed these crimes or witnessed them. The many dedications to Serra in California are honoring a mass murderer. His canonization will forever taint the record of Pope Francis, who is often celebrated as a reformer.

In the wake of calls for racial justice in 2020, this history is becoming more widely known, and the first Serra statues are being removed. The myth of the friendly California missions has no place in the 21st century, and Castillo’s book should help us all to put it to rest.

Additional reading

-

Junípero Serra’s brutal story in spotlight as pope prepares for canonisation

The Guardian, September 23, 2015 -

Junipero Serra was a brutal colonialist. So why did Pope Francis just make him a saint?

Vox, September 24, 2015 -

‘By Their Fruit They Will Be Known’: Junipero Serra as Indian Killer

Indian Country Today, October 14, 2015 -

Sainthood of Junípero Serra Reopens Wounds of Colonialism in California

New York Times, September 29, 2015

-