User: Eloquence

Latest reviews

» View all

Never Flinch once again stars Stephen King’s favorite heroine of the last decade, Holly Gibney.

Holly was first introduced in Mr. Mercedes (2014), where she was a neurotic but capable woman who helped retired detective Bill Hodges to go up against a murderous psychopath named Brady Hartsfield. Since then, King has developed Holly into the leader of a detective agency, who has confronted evil of both the supernatural and the regular human variety.

In Never Flinch, Holly has to juggle two competing priorities. On the one hand, there’s a serial killer on the loose in her hometown, and one of the detectives assigned to the case is asking for her help. On the other hand, she has a new client—a prominent feminist activist who has enlisted her as a bodyguard against anti-abortion fanatics.

The most original idea in the novel is the serial killer’s motive. Without spoiling anything, suffice it to say that he’s very convinced that he’s making an important point by killing random strangers.

The feminist activist who hires Holly, Kate McKay, also keeps the story interesting. In an effort to push for women’s rights, she openly seeks confrontation even in the most conservative US states. As a client, she makes Holly’s work to protect her almost impossible. And someone really is out to get her.

Eventually, and with some suspension of disbelief on the reader’s part, the different threads come together. Holly’s best friends, Jerome and Barbara Robinson, also get pulled into the story, drawn in by a jazz and gospel singer named Sista Bessie.

King capably builds the suspense, and once I was hooked, I found it hard to put the book down. Unfortunately, the payoff isn’t quite commensurate with the build-up. Strands of character development and backstory are left hanging. In their place we get a somewhat conventional villain arc.

Leaving you a bit hungry is not the worst thing you can say about a book, and if Mr. King still has more books to gift his constant readers, I suspect we’ll hear from some of these characters again.

Northway Games is a Canadian indie game development studio based in Vancouver, led by Sarah and Colin Northway. I Was a Teenage Exocolonist, released in 2022, is their most ambitious game to date.

They aptly describe it as a “narrative deckbuilding life sim”; it also incorporates elements of visual novels and dating sims. Playing with the I Was a Teenage Werewolf trope, the title winks at sci-fi pulp, but the story mostly plays it straight.

You are a crèche kid who was born in space during the twenty-year voyage of the Stratospheric to the planet Vertumna. After a preamble during which you can customize your character a bit, the game starts in earnest on the planet. Starting at age 10, you play until your character turns twenty; then you see an epilogue informed by your choices.

Named after the Roman god of seasons, Vertumna undergoes five seasons each year: Quiet, Pollen, Dry, Wet, and Glow. You make choices every month about which stats to raise through activities such as planting crops, learning engineering, or playing sportsball (sic!).

Before choosing your monthly activity, you can walk around the colony a bit. At first, you’re not allowed outside its walls; once you earn permission you can also explore the planet itself, where you advance through a set of events and encounters placed on the map. A stress score keeps you in check and has to be regularly lowered through relaxation.

You explore the planet by walking a path that occasionally branches, progressing from one event to another. (Credit: Northway Games. Fair use.)

Interactive fiction with stats

The narrative plays out mainly in text and occasionally in large, static images. It’s driven both by who you talk to and what activities you choose, and by unavoidable key events. Vertumna is not quite Ceti Alpha V, but the planet’s flora and fauna is understandably not thrilled to be colonized and exploited, putting the settlers under constant threat.

When I say “mostly in text”, I should emphasize that there’s a fair bit of it. Even mundane events often get a paragraph or two of introductory text, and dialogue is written in the third person, like this:

Rex snorts and shakes his head. “Aw, nah, uh, this just happens sometimes, you know? After that whole fight with Vace, people got all these copycat ideas, you know, like, thinkin’ if they pushed me around a bit too, Vace would like them more.”

“People are like that sometimes,” he says, sagely. “They can be chill about hanging out in private, but around their friends, they don’t want anything to do with you. And if the bigger dog attacks, well, they wanna be on that puppy’s side, not yours.”

Rex shrugs one shoulder, indifferent. “It’s fine,” he says. “They’ll remember what I’m good at and come sneaking back eventually.”

This is in contrast with many visual novels, where dialogue is often shown next to a highlighted character. The longer form gives the story a bit more texture, but it may also give some players more reading fatigue; personally, I found myself skimming a bit, especially during low-stakes or no-stakes segments.

The choices available to you are constrained by your stats, which you raise with monthly activities. That means you’ll only see a particular slice of the game in one playthrough—e.g., if you max out engineering and organizing skills, you won’t see much of the branches related to combat.

Although described as a deckbuilder, the card game has more in common with Poker than with “Slay the Spire”. You play without an opponent, and without the addictive challenges and combinatorics of something like “Balatro”. (Credit: Northway Games. Fair use.)

Deck and gear

Raising your stats and advancing through events often involves playing a short card game. There’s no opponent—you play a Poker-like game towards a target score. The game gives you the option to play in easy or hard mode. At least in easy mode, you can often still beat the mini-game by incurring a stress penalty.

To make things a bit more interesting, you can earn more points (kudos) if you hit the goal precisely. Kudos let you purchase “gear” cards, which you can equip to level up particular stats.

The combined mechanics are not terrifically well-explained (e.g., when you purchase gear, it doesn’t make it obvious how the “equip” mechanic works), but they do become clear over time. That’s somewhat consistent with the game’s expectation of repeated playthroughs.

Building a world

What makes I Was a Teenage Exocolonist truly special are not the mechanics, but the worldbuilding. Vertumna is beautifully drawn, and watching the planet change through the seasons greatly increases the immersion. The music is excellent and suits the game’s mood—slow-paced but suspenseful.

The planet’s lifeforms are described in rich detail, and there are many secrets to uncover if you’re willing to take risks. When the colony faces its first major crisis, you are there with them, hoping you survive—but you can’t be entirely sure, because people most certainly die in this game.

One of the most fascinating aspects of the game is the relationship of the colonists with Earth. Without giving anything away, suffice it to say that the exocolonists on the Stratospheric are a group with a cultural identity entirely of their own.

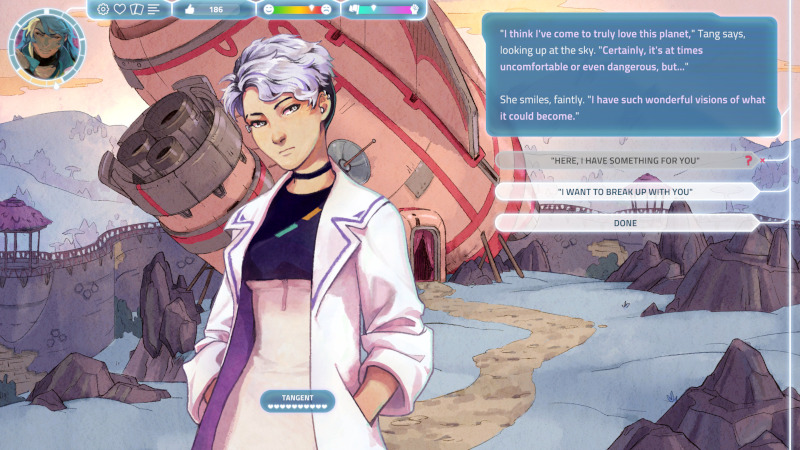

As you enter your later teenage years, you can attempt to date one of the other characters in the game. Even if things start out well, the game may still punch you in the gut later. This screenshot also highlights the stress mechanic—note the worn-down player avatar in the top left. (Credit: Northway Games. Fair use.)

Putting it all together

There’s so much evident labor of love in this game that I can’t help but give it five stars. But if I’m honest, it’s more of a 4.5, because not everything about it worked for me. There are three points of frustration I experienced playing it:

-

The gameplay loop in the colony is a bit tedious until you can go outside. For my next playthrough, I know to level up toughness and bravery early (which tends to involve sports or militaristic activities). Early on, it would have been nice to be able to join guided expeditions, or to get to know the planet in other ways.

-

The card game didn’t really “click” for me in the way that many deckbuilders have. The lack of an opponent and the limited combinatorics meant that I ended up mostly just advancing through these challenges as quickly as possible. I’m going to try again at the higher difficulty, but I was a little trepidatious to do so, because …

-

The stats system can be quite punishing. Choices are frequently unavailable to you based on your stats; even if you have spent many months of game time grinding a particular stat, it may not be quite high enough to do what you want to do. (At one point, I needed “persuasion at 100”, when it was “only” at 91.) There’s no “low chance of success”—the choice will just be locked.

So, mechanically, the game didn’t quite come together for me in the way I hoped. Lovers of dating sims should also be aware that the dating mechanics are fairly limited. They don’t influence the game much, and they don’t necessarily hold a promise of a “happily ever after”.

Still, I enjoyed my time on Vertumna enough to give it at least a second playthrough. I really do want to see what some of the other branches hold, what secrets I may have missed, and where I could have achieved a better outcome.

That’s why, ultimately, I highly recommend I Was a Teenage Exocolonist. If an immersive, text-heavy adventure on another world sounds appealing to you, you’re sure to get something out of it that will stay with you.

Having never seen the musical, I quite enjoyed the first of the two Wicked movies. The sequel picks up where we left off, with Elphaba (Cynthia Erivo) now staging a one-witch-rebellion against the empire of Oz.

The plot gets messy fast, as Wicked: For Good attempts to account for the events of The Wizard of Oz with its own unique spin on what happened.

It’s a fun idea, but unfortunately, the pacing doesn’t quite work. Characters like Elphaba’s sister Nessa behave in ways that don’t make sense for the people we got to know in the first film. To borrow a phrase from Ryan George, the reason why people do things seems to be “so the movie can happen”.

The world of Wicked still looks dazzling, and Erivo is wonderfully expressive as Elphaba, making her character’s actions almost believable. Jeff Goldblum as the wizard gets to perform a great little number about truth and belief, and Ariana Grande-Butera lends her extraordinary vocal talents to, well, some rather middling lyrics.

It’s the writing that’s mostly at fault for things never really coming together. Aside from inconsistent pacing and implausible character developments, the score lacks musical numbers with the same verve that “Popular” or “Dancing Through Life” brought to part one. As a result, the movie feels unbalanced and overwrought.

Perhaps, if the producers had resisted the urge to split the story into two movies, it would have worked better. As it is, viewers of the first film will still want to see the sequel, but may wonder what could have been.

Bio

My name is Erik Moeller. I am currently the primary developer of lib.reviews. Lots of work to do! I also write reviews, primarily of non-profit media, but also of movies, books, products, software, and other things.

If you have feedback on any of my reviews, you can email me at erik@permacommons.org.

Registration date:

Sat Jul 30 2016 05:47:42 GMT-0400 (Eastern Daylight Time)

Team memberships:

- Interactive Fiction moderator founder

- Bundle for Racial Justice and Equality moderator founder

- Edu by Video moderator founder

- Developers moderator founder

- Indie bundle for Palestinian Aid moderator founder

- Linux Hardware

- F-droid reviews

- Language Learning moderator founder

- Vegans

- Nonprofit Media moderator founder

- Email newsletters moderator founder