Reviews by Eloquence

Never Flinch once again stars Stephen King’s favorite heroine of the last decade, Holly Gibney.

Holly was first introduced in Mr. Mercedes (2014), where she was a neurotic but capable woman who helped retired detective Bill Hodges to go up against a murderous psychopath named Brady Hartsfield. Since then, King has developed Holly into the leader of a detective agency, who has confronted evil of both the supernatural and the regular human variety.

In Never Flinch, Holly has to juggle two competing priorities. On the one hand, there’s a serial killer on the loose in her hometown, and one of the detectives assigned to the case is asking for her help. On the other hand, she has a new client—a prominent feminist activist who has enlisted her as a bodyguard against anti-abortion fanatics.

The most original idea in the novel is the serial killer’s motive. Without spoiling anything, suffice it to say that he’s very convinced that he’s making an important point by killing random strangers.

The feminist activist who hires Holly, Kate McKay, also keeps the story interesting. In an effort to push for women’s rights, she openly seeks confrontation even in the most conservative US states. As a client, she makes Holly’s work to protect her almost impossible. And someone really is out to get her.

Eventually, and with some suspension of disbelief on the reader’s part, the different threads come together. Holly’s best friends, Jerome and Barbara Robinson, also get pulled into the story, drawn in by a jazz and gospel singer named Sista Bessie.

King capably builds the suspense, and once I was hooked, I found it hard to put the book down. Unfortunately, the payoff isn’t quite commensurate with the build-up. Strands of character development and backstory are left hanging. In their place we get a somewhat conventional villain arc.

Leaving you a bit hungry is not the worst thing you can say about a book, and if Mr. King still has more books to gift his constant readers, I suspect we’ll hear from some of these characters again.

Northway Games is a Canadian indie game development studio based in Vancouver, led by Sarah and Colin Northway. I Was a Teenage Exocolonist, released in 2022, is their most ambitious game to date.

They aptly describe it as a “narrative deckbuilding life sim”; it also incorporates elements of visual novels and dating sims. Playing with the I Was a Teenage Werewolf trope, the title winks at sci-fi pulp, but the story mostly plays it straight.

You are a crèche kid who was born in space during the twenty-year voyage of the Stratospheric to the planet Vertumna. After a preamble during which you can customize your character a bit, the game starts in earnest on the planet. Starting at age 10, you play until your character turns twenty; then you see an epilogue informed by your choices.

Named after the Roman god of seasons, Vertumna undergoes five seasons each year: Quiet, Pollen, Dry, Wet, and Glow. You make choices every month about which stats to raise through activities such as planting crops, learning engineering, or playing sportsball (sic!).

Before choosing your monthly activity, you can walk around the colony a bit. At first, you’re not allowed outside its walls; once you earn permission you can also explore the planet itself, where you advance through a set of events and encounters placed on the map. A stress score keeps you in check and has to be regularly lowered through relaxation.

You explore the planet by walking a path that occasionally branches, progressing from one event to another. (Credit: Northway Games. Fair use.)

Interactive fiction with stats

The narrative plays out mainly in text and occasionally in large, static images. It’s driven both by who you talk to and what activities you choose, and by unavoidable key events. Vertumna is not quite Ceti Alpha V, but the planet’s flora and fauna is understandably not thrilled to be colonized and exploited, putting the settlers under constant threat.

When I say “mostly in text”, I should emphasize that there’s a fair bit of it. Even mundane events often get a paragraph or two of introductory text, and dialogue is written in the third person, like this:

Rex snorts and shakes his head. “Aw, nah, uh, this just happens sometimes, you know? After that whole fight with Vace, people got all these copycat ideas, you know, like, thinkin’ if they pushed me around a bit too, Vace would like them more.”

“People are like that sometimes,” he says, sagely. “They can be chill about hanging out in private, but around their friends, they don’t want anything to do with you. And if the bigger dog attacks, well, they wanna be on that puppy’s side, not yours.”

Rex shrugs one shoulder, indifferent. “It’s fine,” he says. “They’ll remember what I’m good at and come sneaking back eventually.”

This is in contrast with many visual novels, where dialogue is often shown next to a highlighted character. The longer form gives the story a bit more texture, but it may also give some players more reading fatigue; personally, I found myself skimming a bit, especially during low-stakes or no-stakes segments.

The choices available to you are constrained by your stats, which you raise with monthly activities. That means you’ll only see a particular slice of the game in one playthrough—e.g., if you max out engineering and organizing skills, you won’t see much of the branches related to combat.

Although described as a deckbuilder, the card game has more in common with Poker than with “Slay the Spire”. You play without an opponent, and without the addictive challenges and combinatorics of something like “Balatro”. (Credit: Northway Games. Fair use.)

Deck and gear

Raising your stats and advancing through events often involves playing a short card game. There’s no opponent—you play a Poker-like game towards a target score. The game gives you the option to play in easy or hard mode. At least in easy mode, you can often still beat the mini-game by incurring a stress penalty.

To make things a bit more interesting, you can earn more points (kudos) if you hit the goal precisely. Kudos let you purchase “gear” cards, which you can equip to level up particular stats.

The combined mechanics are not terrifically well-explained (e.g., when you purchase gear, it doesn’t make it obvious how the “equip” mechanic works), but they do become clear over time. That’s somewhat consistent with the game’s expectation of repeated playthroughs.

Building a world

What makes I Was a Teenage Exocolonist truly special are not the mechanics, but the worldbuilding. Vertumna is beautifully drawn, and watching the planet change through the seasons greatly increases the immersion. The music is excellent and suits the game’s mood—slow-paced but suspenseful.

The planet’s lifeforms are described in rich detail, and there are many secrets to uncover if you’re willing to take risks. When the colony faces its first major crisis, you are there with them, hoping you survive—but you can’t be entirely sure, because people most certainly die in this game.

One of the most fascinating aspects of the game is the relationship of the colonists with Earth. Without giving anything away, suffice it to say that the exocolonists on the Stratospheric are a group with a cultural identity entirely of their own.

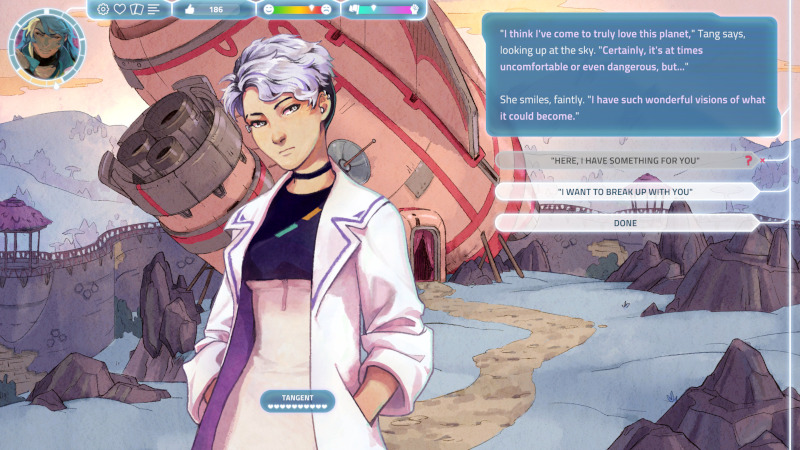

As you enter your later teenage years, you can attempt to date one of the other characters in the game. Even if things start out well, the game may still punch you in the gut later. This screenshot also highlights the stress mechanic—note the worn-down player avatar in the top left. (Credit: Northway Games. Fair use.)

Putting it all together

There’s so much evident labor of love in this game that I can’t help but give it five stars. But if I’m honest, it’s more of a 4.5, because not everything about it worked for me. There are three points of frustration I experienced playing it:

-

The gameplay loop in the colony is a bit tedious until you can go outside. For my next playthrough, I know to level up toughness and bravery early (which tends to involve sports or militaristic activities). Early on, it would have been nice to be able to join guided expeditions, or to get to know the planet in other ways.

-

The card game didn’t really “click” for me in the way that many deckbuilders have. The lack of an opponent and the limited combinatorics meant that I ended up mostly just advancing through these challenges as quickly as possible. I’m going to try again at the higher difficulty, but I was a little trepidatious to do so, because …

-

The stats system can be quite punishing. Choices are frequently unavailable to you based on your stats; even if you have spent many months of game time grinding a particular stat, it may not be quite high enough to do what you want to do. (At one point, I needed “persuasion at 100”, when it was “only” at 91.) There’s no “low chance of success”—the choice will just be locked.

So, mechanically, the game didn’t quite come together for me in the way I hoped. Lovers of dating sims should also be aware that the dating mechanics are fairly limited. They don’t influence the game much, and they don’t necessarily hold a promise of a “happily ever after”.

Still, I enjoyed my time on Vertumna enough to give it at least a second playthrough. I really do want to see what some of the other branches hold, what secrets I may have missed, and where I could have achieved a better outcome.

That’s why, ultimately, I highly recommend I Was a Teenage Exocolonist. If an immersive, text-heavy adventure on another world sounds appealing to you, you’re sure to get something out of it that will stay with you.

Having never seen the musical, I quite enjoyed the first of the two Wicked movies. The sequel picks up where we left off, with Elphaba (Cynthia Erivo) now staging a one-witch-rebellion against the empire of Oz.

The plot gets messy fast, as Wicked: For Good attempts to account for the events of The Wizard of Oz with its own unique spin on what happened.

It’s a fun idea, but unfortunately, the pacing doesn’t quite work. Characters like Elphaba’s sister Nessa behave in ways that don’t make sense for the people we got to know in the first film. To borrow a phrase from Ryan George, the reason why people do things seems to be “so the movie can happen”.

The world of Wicked still looks dazzling, and Erivo is wonderfully expressive as Elphaba, making her character’s actions almost believable. Jeff Goldblum as the wizard gets to perform a great little number about truth and belief, and Ariana Grande-Butera lends her extraordinary vocal talents to, well, some rather middling lyrics.

It’s the writing that’s mostly at fault for things never really coming together. Aside from inconsistent pacing and implausible character developments, the score lacks musical numbers with the same verve that “Popular” or “Dancing Through Life” brought to part one. As a result, the movie feels unbalanced and overwrought.

Perhaps, if the producers had resisted the urge to split the story into two movies, it would have worked better. As it is, viewers of the first film will still want to see the sequel, but may wonder what could have been.

After Knives Out (set in an opulent mansion) and Glass Onion (set on a tech billionaire’s private island), director Rian Johnson sought a very different setting for Benoit Blanc’s third mystery. He found it in a rural parish in upstate New York, to which we are introduced by a likeable protagonist with the unlikely name Jud Duplenticy (Josh O’Connor).

Father Jud is a young priest and former boxer who has been sent to the parish after an altercation. In the film’s first act, he gradually introduces us to the community around Our Lady of Perpetual Fortitude: the combative Monsignor Jefferson Wicks (Josh Brolin); his devout right-hand woman Martha Delacroix (Glenn Close); assorted churchgoers. The act ends with a seemingly impossible murder being committed.

This, of course, is what summons private detective Blanc (Daniel Craig). While he makes it very clear that he is not a man of faith, he nevertheless takes Father Jud under his wing and relies on him to help investigate the murder.

What follows is a romp every bit as delightful and convoluted as the other entrants in the Knives Out series. What’s different this time is that Rian Johnson has a bit more to say — on how faith can be abused; on the important social work that often goes hand in hand with religion; on grace as an idea that transcends belief itself.

It’s not perfect, of course. Rian Johnson employs a familiar formula, combining somewhat predictable twists with an absurd central mystery only Benoit Blanc can figure out. Suspension of disbelief is very much part of the price of admission. You gotta have a little faith, in other words.

Benoit Blanc remains a delightful character, and Daniel Craig is clearly still having fun with the part. I look forward to the gentleman detective’s next case.

Roguelike deckbuilders are one of my favorite indie gaming genres. Definitive titles like Slay the Spire (review) offer 100+ hours of replay value as you explore their combinatorial depths.

Roguebook came out in the summer of 2021 and was developed by Belgian studio Abrakam. The game’s premise is that the playable characters are trapped inside the eponymous book, and must fight their way out using cards.

That book metaphor shows up in a few places: the overworld is mapped out using ink and paintbrushes, and you collect pages to unlock meta-progression between runs.

But it’s a shallow conceit, and the world is a very run-off-the-mill, generic fantasy world you’ve seen a million times; the name “Faeria” tells you everything you need to know. There’s no real narrative beyond “we’re in a book!”. The brief character bios are mostly about their skillset, and intermittent “story” moments are isolated and non-specific. Even Slay the Spire, not known for its story, does a better job connecting its atmosphere and lore.

Still, there are a few things to like about Roguebook, starting with the overworld.

Echoes of Might and Magic

Maps tend to be the genre’s Achilles heel: usually you just wander one of two or three pre-defined paths and pick which monsters to fight. The worst offender may be Dicey Dungeons (review), an otherwise excellent game: the level maps are glorified interstitials that show you which battles lie ahead.

Before Roguebook, the best maps I’ve seen are the ones in Across the Obelisk, which offer interesting branches and fast travel, and are beautifully designed. But the maps are static images overlaid with random events. Not very roguelike!

In contrast, Roguebook’s overworld is a randomly generated multi-screen hexagon map you travel across. You gradually reveal it using brushes and ink you earn from battles or as part of other rewards. Loot and enemies are scatted across the map. Many battles are entirely optional if you just want to go for the boss.

Yes, that is a turtle flying on a magic carpet. (Credit: Abrakam. Fair use.)

The level-specific buildings, terrain and vegetation give the overworld a much more lived-in feeling than what you can expect from most deckbuilders. It feels just a tiny bit like the gorgeous maps in a beloved game like Heroes of Might and Magic. But I don’t want to exaggerate — the amount of “stuff” that happens on these maps is much more limited.

Still, it’s undeniably more fun to crawl these maps than it is to pick a path in Slay the Spire. There’s loot everywhere, there are towers and runes that reveal more tiles and treasures, and the scarcity of ink forces you to prioritize. As shown in the screenshot, you’ll usually only see parts of the map before progressing to the next level.

Tag Team Battles

Once you’re in a battle, it looks like any other roguelike deckbuilder: player characters on the left, enemies on the right, cards at the bottom, along with your draw pile, discard pile, and dissolve pile.

There are, of course, a few specifics. You’re always in a tag team. When you start a run, you get to choose two heroes from a total unlockable set of four (one more available as DLC). There are some nice touches here: the game has a bit of flavor speech for each hero and for the interactions between your pair. It’s not much, but it shows an attention to detail that lifts the game above feeling like a genre clone.

Defense points are shared across heroes, which keeps things simple. The position (front or back) does matter (e.g., front hero takes damage first), and quite a few mechanics are tied to hero position. For example, one card powers up every time you switch positions, which can make it extremely powerful in a long battle.

In addition, heroes can recruit “allies”. When I first drew a card called “Windstorm Colossus”, I was hoping for a dramatic addition to the gameplay:

Alas, once you play them, allies just show up as unmoving, barely discernible portrait images with a number. That takes away a bit from the atmosphere! Allies can cause damage or have their own powers (like “draw a card” or “gain some energy”) that you can selectively activate.

Alas, once you play them, allies just show up as unmoving, barely discernible portrait images with a number. That takes away a bit from the atmosphere! Allies can cause damage or have their own powers (like “draw a card” or “gain some energy”) that you can selectively activate.

Despite that, the ally mechanic is interesting, if a bit overpowered; it lets you effectively build a little army fighting alongside your heroes.

In addition, heroes and the team as a whole have abilities they can unlock as you increase the number of cards in your deck. Combined with treasure items that are everywhere, and gemstones you can craft onto your cards to modify them, there is quite a bit of depth once you look past the familiar facade.

Limited Difficulty

The difficulty progression is one of the game’s weaker points. It took me just 2-3 hours to beat a run, and without spoiling anything, there’s not much to it — not even the typical “that was the fake boss, now meet the real boss” final battle.

When I finally beat Slay the Spire’s Corrupt Heart, I yelled out in celebration. It was a hard-won victory that was only possible after truly mastering the game’s mechanics. You’re unlikely to have such a moment in Roguebook.

The game does offer a wide range of difficulty modifiers in the “epilogue” (its New Game Plus); if you beat it with those modifiers, you earn more “pages”, which you can use to unlock more meta-progression. But that doesn’t quite have the same draw as “must finally defeat the uberboss”.

The different characters also aren’t different enough to make you want to spend a lot of time with each new one. This is where Slay the Spire shows its superior game design: change characters, and it feels like you’re playing a new game; the mechanics really are that different. In contrast, with Roguebook, I sometimes got my two characters confused because their talents were so similar.

The combat screen should look familiar to anyone who’s played a deckbuilder. The “Soul Eater” mini-boss depicted here looks creepy, but is very easy to beat. (Credit: Abrakam. Fair use.)

The enemy design is moderately creative. You’ve got your bandits and sheep, but then you’ve also got an aerial island world populated by Ewok-like creatures that throw frogs at you. There’s just enough animation and speech for battles to feel alive and interesting.

There’s a large enough variety of bosses and mini-bosses that runs don’t quickly become repetitive, with a few novel mechanics thrown in here and there (my favorite is a boss that incarnates into other creatures while you fight him).

Hidden Gemstones

Earlier, I briefly mentioned the mechanic of modifying cards with gemstones. It’s in fact fairly well-developed: you find gems on the map or as rewards, and you can bolt them onto compatible cards to get various point or behavior modifiers (e.g., “decrease cost when you’re in the back”). “Flash gems” can be used once, and offer higher rewards (e.g., a mega-block).

But they stand out for another reason: gem mines. Unlocked via meta-progression, they start to appear randomly on each level map, and offer rooms filled with rewards. The catch is that each room has a custom trap you have to defeat.

These are regular card battles, but with trap-specific mechanics. For example, one trap door must be hit with exactly 33 points to be defeated. If you don’t make it in time, the passage door collapses, and your characters acquire injuries (unplayable extra cards) that last until the next level.

I’ve not noticed any other mid-game or late-game elements of similar complexity, but this one was a nice surprise. 30 hours in I encountered a beautifully designed “face in the wall” trap boss I’d never seen before — that’s the kind of variety you’re hoping for from a deckbuilder.

The Verdict

Ultimately, Roguebook is a good game that could have been great. Its biggest weakness is the lack of any coherent narrative or character development. A game with a sufficiently original art style can make up for that (Meteorfall: Krumit’s Tale comes to mind), but despite a few nice touches, the world of Roguebook is a bit too generic to be awesome.

The publisher follows the not atypical indie gaming strategy of overpricing the game ($25 as the Steam listing price) while regularly making it available at a massive discount (right now, GOG.com has it for $2.49). The idea, of course, is to convince you that you’re getting a superb deal.

Truth be told, at that price, it’s a steal for any fan of the genre, and it should give you at least 5-10 hours of enjoyment; more if you’re like me and want to at least unlock all the cards and relics.

I played it on my 2019 Linux machine mostly without issues. The game does get a bit sluggish when you build really large card stacks, but I experienced no crashes or game-breaking bugs.

Spirits tend to have unfinished business. That’s how it is in Cozy Grove, where your job is to wander a haunted island as a “spirit scout” and to help one ghostly bear after another to move on.

In the process, you get to place decorations, raise animals, go fish, cook meals, earn achievements, throw stones, expand your wardrobe, buy and sell, and perform more fetch quests than you’ve ever wanted to.

While you can keep grinding for hours, the story only progresses a little bit every day. This is one of those games that wants you to keep coming back in small doses.

If you enjoyed Animal Crossing, you’ll almost certainly get a kick out of Cozy Grove. The game’s variety, atmosphere and story moments make the grind of fetch quest after fetch quest palatable. Personally, I put more than 90 hours into it, so I’m rounding up a 4.5 star rating.

How you want to decorate your camp site is up to you, but it influences what kind of plants and animals will thrive there. (Credit: Spry Fox LLC. Fair use.)

If you talk to me about computers for more than a few minutes, I’ll inevitably bring up the C64. A key machine from my childhood, it opened up an entire a world for me. Together with my sibling and my father, it’s where I played games for countless hours, typed in BASIC programs, and discovered the world of bulletin board systems.

In the 1980s, print magazines were vitally important as a guide. I was not in the UK, so I did not hear of Zzap!64 until much later. But in the British C64 community, it was legendary for its unvarnished and honest reviews, written by gamers for gamers. And with it, Julian “Jaz” Rignall started his own legend as a games journalist.

Before landing his poorly paid dream job, teenage Jaz made a name for himself by winning arcade tournaments in the early 1980s, racking up unthinkable scores that required absurdly fast reflexes and exploits of a machine’s weaknesses. The three letter nickname is from the high-score tables.

Games journalism at that time was often still a stuffy business: impeccable prose by writers who had no idea what made games fun. When Chris Anderson (who later founded IGN) looked for gamers who could help him launch a C64 magazine that would do things differently, Jaz made the list.

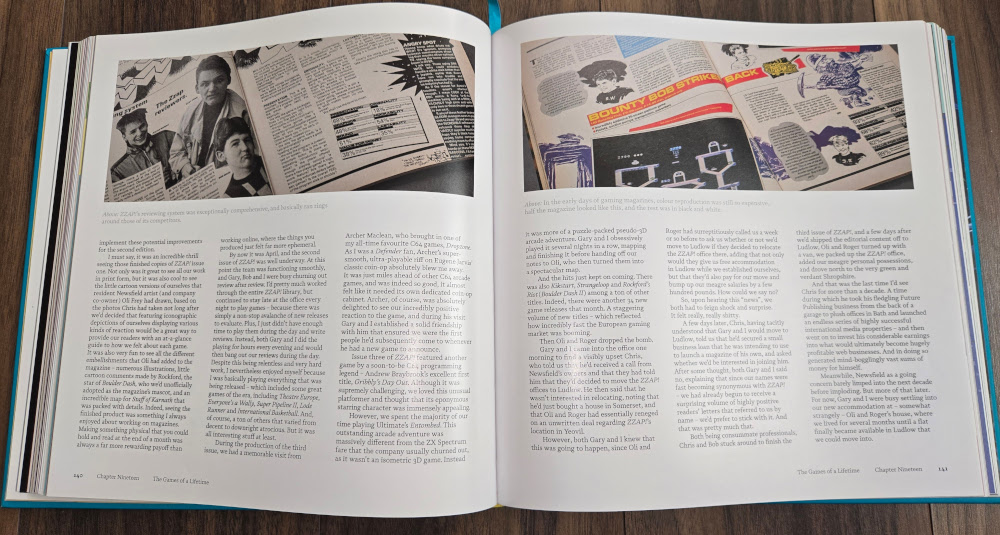

The years Jaz worked at Zzap!64 and, later, Mean Machines are the heart of his games-centric memoir “Games of a Lifetime”. The book inspired me to make my way through old editions of Zzap!64 on my tablet. It’s a fun read—full of wacky illustrations of reviewer reactions to the games, a dedicated section for interactive fiction and RPGs, all in a casual writing style reflecting the young audience.

In addition to many beautiful screenshots, “The Games of a Lifetime” also features a few select photos from the author’s life that relate to the history of games or the magazines he wrote for. (Own photo. License: CC-BY-SA.)

But Jaz is a lifetime gamer, and the book extends all the way into the 2020s. Jaz shares his multi-year love affair with World of Warcraft, his passion for racing games like the Gran Turismo series, and his admiration for indie walking sims like Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture.

This is interspersed with stories from his life: work beyond gaming for corporate giants like Bank of America and Walmart; friendships and relationships; hobbies and accidents. Not all of that is page turner material, but the author refocuses quickly on games he associates with a particular period in his life.

As is typical for Bitmap Books titles, the book has large, gorgeous screenshots of the games it covers, making it a fun coffee table addition. If you’re a huge Nintendo fan, be advised that Jaz doesn’t cover many Nintendo titles after the N64 era — it’s just not his thing. They’re the games of his lifetime, after all.

If we lived forever, I wouldn’t mind dedicating a small percentage of forever to playing every old game for the C64, for the Amiga, for the SNES, and comparing notes. But in the absence of immortality, for any old gamer, books and magazines feel like a pinball racing through your brain, bouncing off old memories, and creating new ones. If you’re one of us, consider taking the plunge.

Catherine Nixey’s first book, The Darkening Age (review), told the sobering story of how Christianity’s rise required the persecution of all opposing beliefs: the destruction of pagan temples and statues, the burning of books, the prohibition of worship.

Her second work, Heretic: Jesus Christ and the Other Sons of God, focuses on Jesus himself. Nixey observes that, whatever the historicity of Jesus, what we are left with are stories that don’t describe one Jesus Christ, but many.

The bizarre Infancy Gospel of Thomas tells of a son of God who, as a child, kills other children out of spite—reminiscent of Anthony Fremont in “It’s a Good Life” wishing his victims into the cornfield. In the Gospel of Basilides, it’s not Jesus who was crucified, but Simon of Cyrene, while Jesus laughed at him.

Nixey vividly describes the ancient world as a place where the kinds of miracles the New Testament attributes to Jesus were commonplace claims by many self-anointed prophets and miracle workers. Raising the dead, healing the sick? Not a one-time deal.

It’s no surprise, then, that the Acts of Peter describe a magic duel between Simon Magus and Apostle Peter, or that Jesus was sometimes depicted as a wand-carrying wizard by his own followers.

Despite brutal attempts to suppress “heretical” Christian beliefs, Nixey traces the legacy of these sacred texts in literature, art, and surviving Christian traditions like Mandaeism and Ethiopian Christianity. All, of course, view theirs as the orthodox truth.

You’re a wizard, Jesus: In this 4th century depiction, Jesus multiplies loaves and and fishes with a wand.

Like the stories of Jesus, the concept of monotheism itself can be traced to precursor beliefs. Nixey points out that the Bible retains traces of polytheism or henotheism (the worship of one supreme God among many).

One common example is Psalm 82:

“God standeth in the congregation of the mighty; he judgeth among the gods.”

But even Genesis, the very foundation of monotheistic belief, refers to other entities alongside God:

“Let us make humankind in our image” (1:26)

“Behold, the man is become as one of us” (3:22)

“Go to, let us go down, and there confound their language” (11:7)

These are extant references to the Canaanite pantheon; before there was one God, there were many.

Catherine Nixey’s Heretic, despite its sometimes acerbic tone, is not an anti-religious book. It simply documents how religious ideas blend and evolve over time. Any one belief, no matter how fervently held, has its (often contradictory) antecedents and descendents.

Looking at this tapestry of belief, anyone can appreciate that there is beauty in it—but also that those who point at one specific sacred text and say “That’s the one, that’s the one worth killing for!” should make heretics out of us all.

Speculative fiction from the era before the moon landing and the exploration of the solar system occupies a special place in my heart.

Writers from the 1930s, 1940s, and 1950s still dared to dream of life on Mars. Their imaginations had not yet been influenced and constrained by the slow progress of real-world space exploration, or by particular visions of the future like those popularized by Star Trek or The Expanse.

The Science Fiction Hall of Fame, Volume One was published in 1970 and contains a total of 26 stories first published between 1934 and 1963. The book includes 15 stories selected by a vote of the Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America and 11 stories picked by editor Robert Silverberg.

One cannot pick up such an old collection in 2024 without noticing the all-white and almost all-male selection of writers. The stories themselves, too, reflect the prejudices of their era. In “Helen O’Loy”, the perfect robot wife cooks, cleans, and adulates her husband; in “Twilight”, a time traveler from the future remarks on the wonderful music produced by “semicivilized peoples”.

Nevertheless, this collection includes some stories that are well worth your time. There are the classics that have inspired countless adaptations and imitations: “Microscosmic God” about a scientist who creates a civilization; “It’s a Good Life” about an omnipotent child; “Flowers for Algernon” about an intellectually disabled man who is turned into a genius by way of surgery.

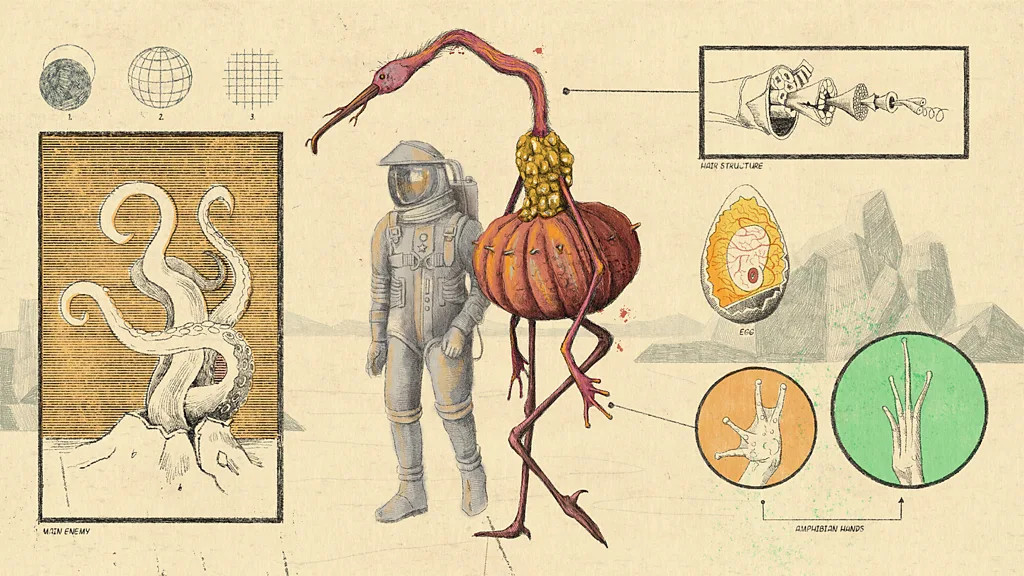

The alien Tweel, depicted here by artist Emmanuel Lafont, is one of the unforgettable characters from “A Martian Odyssey” by Stanley G. Weinbaum. (Credit: Emmanuel Lafont. Fair use.)

The (at least to me) lesser known gems include “Mimsy Were the Borogoves” about children’s toys from the future, “Scanners Live in Vain” about humans bio-engineered to survive space travel, and “Surface Tension” about a civilization of tiny aquatic humanoids and their microbial helpers.

“Scanners Live in Vain” takes an imaginative leap that was still barely plausible in 1953: the idea that space travel causes conscious human beings to suffer and die due to an unexplained condition called “The Great Pain of Space”. Therefore, space travelers have to hibernate under the supervision of caretakers without the ability to feel.

It’s the kind of story unlikely to be written today, but it makes for a fascinating “what if” now. What if space travel had been like that?

Keeping its biases in mind, “The Science Fiction Hall of Fame” remains a useful starting point for exploring this era of speculative fiction. Except Silverberg, all the authors have passed away as of this writing. Their influence on how we think about the future — and the past — endures.

The full list of stories:

- “A Martian Odyssey” by Stanley G. Weinbaum

- “Twilight” by John W. Campbell

- “Helen O’Loy” by Lester del Rey

- “The Roads Must Roll” by Robert A. Heinlein

- “Microcosmic God” by Theodore Sturgeon

- “Nightfall” by Isaac Asimov

- “The Weapon Shop” by A. E. van Vogt

- “Mimsy Were the Borogoves” by Lewis Padgett

- “Huddling Place” by Clifford D. Simak

- “Arena” by Fredric Brown

- “First Contact” by Murray Leinster

- “That Only a Mother” by Judith Merril

- “Scanners Live in Vain” by Cordwainer Smith

- “Mars is Heaven!” by Ray Bradbury

- “The Little Black Bag” by C. M. Kornbluth

- “Born of Man and Woman” by Richard Matheson

- “Coming Attraction” by Fritz Leiber

- “The Quest for Saint Aquin” by Anthony Boucher

- “Surface Tension” by James Blish

- “The Nine Billion Names of God” by Arthur C. Clarke

- “It’s a Good Life” by Jerome Bixby

- “The Cold Equations” by Tom Godwin

- “Fondly Fahrenheit” by Alfred Bester

- “The Country of the Kind” by Damon Knight

- “Flowers for Algernon” by Daniel Keyes

- “A Rose for Ecclesiastes” by Roger Zelazny

The vast number of indie games published every month, on big stores like Steam and on smaller sites like itch.io, can be overwhelming. If a title doesn’t generate a lot of buzz (like Dredge in 2023 or Vampire Survivors in 2022), it’s easy for it to get lost in the shuffle.

Part of the joy of indie gaming is the sense of discovery, when you come across something truly special that very few people are talking about. Debug is a new video game magazine that may reignite that joy among its readers.

Published quarterly out of Norwich in the UK, each issue is packed with previews, reviews, interviews and feature articles, focused entirely on indies.

To give just an example, the third issue featured reviews of Sea of Stars, Bomb Rush Cyberfunk, Cocoon, Viewfinder, Somerville, DungeonGolf, The Many Pieces of Mr. Coo, Everspace 2, Station to Station, Kentucky Route Zero, Boti Byteland: Overclocked, Full Void, Ad Infinitum, Girl Genius, The Repair House, Solar Ash, and WrestleQuest.

In addition to new titles, older indie games are featured in lists such as “the 10 weirdest indie games”, or because they’ve been ported to new platforms (e.g., Kentucky Route Zero was ported to Xbox earlier this year).

A two-page spread from issue 3 about the game “Planet of Lana”. (Credit: Debug. Fair use.)

Just like many indie games, Debug lacks a bit of polish. One writer uses the redundant construction “also …, too” so frequently that I started to find it a bit grating. Issues 1 and 3 accidentally included the same top 10 list. Small things like that. On the other hand, the magazine is visually very appealing and gives a lot of space to the beautiful artwork from the games it features.

The reviews strike a good balance of offering criticism without tearing down the work of indie devs. They often include a second opinion, or pointers to other similar titles players might enjoy. Many titles showcased by Debug have received very little attention on platforms like Steam, so you’re definitely likely to discover something new.

Anyone who’s ever thought about developing an indie game will appreciate the interviews and feature articles that talk more about the process behind the games. But the magazine never feels like inside baseball—despite the name “Debug”, it’s accessible to folks who just want to play games.

As of this writing, the magazine is very affordable, with a US sales price of $10 for the print edition and $4 for the PDF version. I found the ordering process from the US painless, with a very reasonable $7 shipping fee for three print issues. For more than 80 pages of indie goodness, it’s a bargain, and I recommend Debug for all lovers of indie games.