Imperial Twilight

-

www.wikidata.org/wiki/Q60756532

Review sites Goodreads Online stores IndieBound Amazon - history book by Stephen R. Platt

-

1850_Sherwill_5_Stack1B82D-1551765329516.jpg

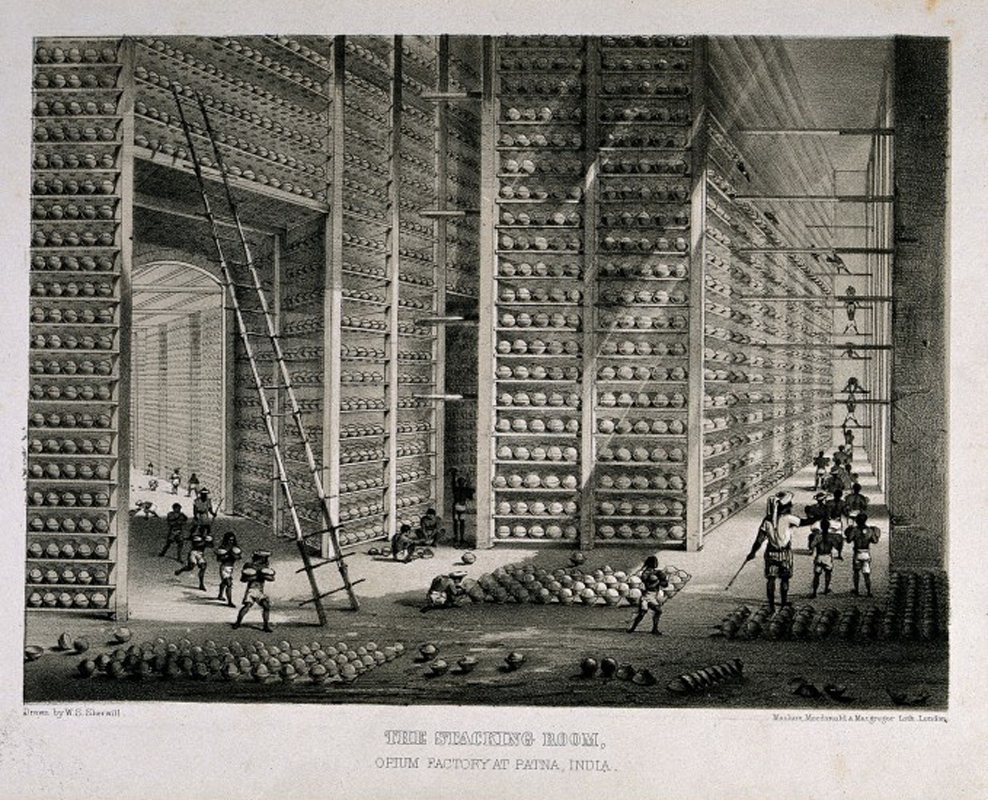

Stacking room at an opium factory in Patna, India (1850).Credit: W. S. Sherwill. CC-0 or public domain.Source data licensing:

Data from Wikidata is available under Creative Commons CC-0.

lib.reviews is only a small part of a larger free culture movement. We are deeply grateful to all who contribute to this movement.Reviews

Please sign in or register to add your own review.

When Britain went to war to sell drugsImperial Twilight: The Opium War and the End of China’s Last Golden Age is an attempt by American historian Stephen Platt to explain the causes of the First Opium War (1839-1842) between the United Kingdom and China under the Qing dynasty, and to contextualize it in the history of the declining Celestial Empire.

Platt is a gifted storyteller, and the book puts significant focus on individual actors. It begins with the story of British merchant James Flint’s ill-fated 1759 expedition to change the conditions under which British traders operated; it ends with the protagonists of the First Opium War, such as Foreign Secretary Lord Palmerston, Chinese anti-drug official Lin Zexu, and William Jardine, one of the leading opium smugglers.

Platt also tells us about some of the domestic threats the Chinese empire was facing during this era: on land, the White Lotus Rebellion that combined political grievances with religious fanaticism; at sea, a formidable united pirate fleet known as the “Red Flag Fleet”, commanded by a female leader, Ching Shih. The Qing dynasty’s ineffective response to these threats is symptomatic of the “imperial twilight” of the book’s title.

Stacking room at an opium factory in Patna, India (1850). (Credit: W. S. Sherwill. Public domain.)Wars for drugs

The foreign opium trade itself had its roots mainly in India, where the East India Company controlled much of its production. Platt explains how the explosion of production and trade turned a luxury drug into a major national health problem for China and drained the domestic economy of silver that was used to pay drug dealers.

After largely unsuccessful efforts to police Chinese traders and users (and a tantalizing flirtation with the idea of legalization), the empire appointed an official named Lin Zexu to a position we might today call a drug czar. Lin cracked down on the the foreign traders who brought opium into the country; he blockaded their ships, seized their opium, and ordered the destruction of more than 1,000 tons of it.

Although no British subjects where physically hurt in this confrontation, the destruction of property—even property whose sale was very much illegal in China—provided a casus belli for the First Opium War, leading to the first of the unequal treaties between China and European powers (and soon, to the Second Opium War).

If you ever wondered why Hong Kong was a British colony until 1997: it was one of the spoils of Britain’s drug wars. These wars forced China to accept the opium trade, and cleared the path to respectability for those who sold the drug. Today, Jardine Matheson, which was originally built on the opium trade, is a $39.5B conglomerate.

Agency and empire

Platt’s central thesis is that the war could have been averted if just a small number of individuals had acted differently: there was significant opposition to the opium trade within Britain; many traders were perfectly happy to play by China’s rules; Lin Zexu overplayed his hand against the British; his British complement, trade superintendent Charles Elliot, made an absurd promise to compensate the opium smugglers that forced the hand of the British government.

It’s a fine hypothesis, but I don’t buy it. The British Empire’s political structure was designed to find accommodations between power factions, with 86% of adult men and 100% of adult women disenfranchised. The legal and illegal traders who wanted to force an opening of China (with preferential treatment for Britain) were an increasingly powerful faction. Britain was aware of China’s inability to defend its coastline.

Sooner or later, a similar combination of means, motive and opportunity would have led to a similar criminal undertaking. This is not an argument against culpability or agency of individuals. But I believe Platt’s view of China is a lot more realistic than his view of the politics of the British Empire.

The verdict

Platt’s book spends almost no time writing about the First Opium War itself, which was, after all, a war in which around 20,000 people—mainly Chinese—were killed or wounded. He says the bare minimum about the Second Opium War, about the concessions China was forced to make to Western powers, about the consequences for ordinary Chinese people.

Nonetheless, this is an insightful, well-researched and highly captivating book. I especially appreciated the author’s efforts to convey the frequent cultural misunderstandings between British and Chinese diplomats and politicians, which heavily contributed to the failure to find common ground peacefully. The book also contains many beautiful black-and-white illustrations and helpful maps.

Stephen Platt’s book is a piece to the puzzle of a history that seems especially important today. China is re-emerging as a superpower—perhaps the superpower—while nationalist rhetoric is back in fashion in Western democracies. If you’re looking for a definitive or systematic history of the Opium Wars, this isn’t it. But if you’re looking for a book that will draw you into the world of the traders and smugglers, scholars and fools in which those wars took place, I recommend Imperial Twilight unreservedly.