Review: The Friendly Orange Glow

The story of PLATO, a computer-based instruction system developed at the University of Illinois, is filled with extraordinary and nearly forgotten precedents in the modern history of computing: for real-time collaboration, multiplayer online gaming, and the beginnings of cyberculture—all in the 1970s.

In The Friendly Orange Glow, Brian Dear has synthesized a research effort spanning decades into the (thus far) definitive history of the PLATO system, its principal architects, its community, and its legacy.

According to Dear (an early user of the system), the book is the result of

over 7 million words of typed transcripts from 1000+ hours of recorded interviews, plus over 13000 emails, plus hundreds (maybe thousands, I’ve lost count) of other materials including magazine and newspaper articles, books, documents, pamplets, videos, photographs, and brochures.

Dear introduces key figures like Donald Bitzer (the charismatic “father of PLATO”) and Daniel Alpert (a longtime champion of the project) while documenting the project’s development stages, from minimalist beginnings to breakthroughs such as the creation of 512x512 resolution touchscreen (!) plasma displays and the TUTOR programming language.

Bitzer and his team fostered a creative, open environment in which high school kids experimented alongside older students and professors. As the PLATO community grew, it created tools for chat & discussion, becoming an online community that would ultimately draw in thousands of people.

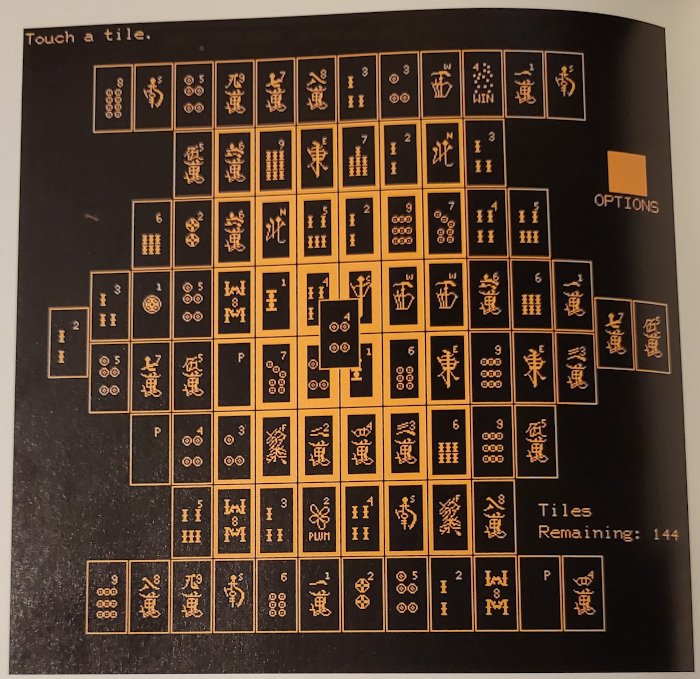

Brodie Lockard’s Mahjong game showcases the graphical capabilities of the system, which were far ahead of microcomputers from the same time period. (Credit: Brodie Lockard; scanned from the book. Fair use.)

Multiplayer Dungeon Crawling 101

As innovative and impressive as the graphical courses developed for PLATO were for the time, many of the most interesting uses of the system had little to do with education. Students used the PLATO terminals for real-time chatter, political organizing, journalism, storytelling, and—games, games, games.

These were multiplayer games with leaderboards and real-time chat, not tiny diversions like NIBBLES.BAS that would later be included with MS-DOS and played by millions of kids. In Empire, players competed to take over the whole galaxy; in Moria, they explored a dynamically generated dungeon (rendered as a tiny 3D wireframe).

The most inspiring story from the book is that of Brodie Lockard. After he became paralyzed as a result of a horrible sports accident, Lockard learned how to use a mouth stick to control a PLATO terminal. Through countless hours of painstaking effort, he created a gorgeous Mahjong game. Later, he (no less painstakingly) re-implemented it for the early Apple Mac under the name Shanghai, and it became a global smash hit for many platforms.

Peering into PLATO’s cave

What was PLATO’s pioneering online community like? How did it behave towards its members? While Brian Dear touches on these questions, this is also an aspect of PLATO examined by researcher Joy Rankin, including in her book A People’s History of Computing.

Rankin has found examples of abusive comments in PLATO’s archives, such as a misogynistic joke that should get a person fired in any professional environment. Prior to the publication of their respective books, Brian Dear wrote a detailed, confrontational critique of several of Rankin’s interpretations (accusing her of “misunderstandings, historical errors, omissions, and confirmation bias”), and things escalated from there.

That’s regrettable, because an examination of PLATO’s community norms and gender dynamics should be part of a comprehensive history of the system. To fill this gap, readers are well-advised to make up their own minds about the evidence that Rankin and Dear have presented.

A legacy of living ideas

In the 1980s and 1990s, PLATO could could well have reached millions of users, much as CompuServe and AOL did years later. As Dear documents in somewhat excruciating detail, the commercialization of the system was botched by Control Data Corporation, whose executives dismissed PLATO’s most innovative uses and regarded microcomputers as annoying toys.

Still, PLATO influenced thousands of minds, and Dear makes it clear that its legacy is far greater than an interesting historical footnote. The people who wrote lessons, apps and games on PLATO would go on to create their own milestones in computing history, from Lotus Notes to Wizardry.

At 640 pages (hardcover), The Friendly Orange Glow is a hefty tome. It could have been 100 pages shorter without losing anything essential—perhaps in exchange for some more analysis of the aforementioned community dynamics. Nonetheless, an accurate modern history of technology and cyberculture must look beyond Silicon Valley, and Brian Dear’s book is an important contribution to such a broader view.