Review: Gabriel Knight: Sins of the Fathers

Gabriel Knight is a lout. He is also the owner of a bookstore in New Orleans’ famous French Quarter, and a struggling novelist researching a spree of apparently voodoo-inspired killings that have gripped the city. Through his friend Frank Mosely, a police detective investigating the killings, he is able to learn more about the case than what’s reported in the papers.

As he travels the city and speaks to people who may be able to shed light on the case, his shop assistant, Grace Nakimura, minds the store, takes messages for Gabriel, and undertakes research on his behalf. Gabriel is a womanizer, and Grace knows him well enough to keep some distance between them.

What could be the setup for a movie or a TV show is in fact the plot of Gabriel Knight: Sins of the Fathers, a 1993 video game designed by Jane Jensen and published by Sierra. The game is fully voice-acted by a cast that includes Tim Curry (Gabriel Knight), Mark Hamill (Frank Mosely), Leah Remini (Grace Nakimura), and Michael Dorn (Dr. John).

You control Gabriel’s actions in typical point and click fashion: click on hotspots on the screen and interact with them using various actions (look, operate, talk to, etc.). As is typical for the genre, you can carry as much stuff with you as you want, and you’ll want to pick up anything you can.

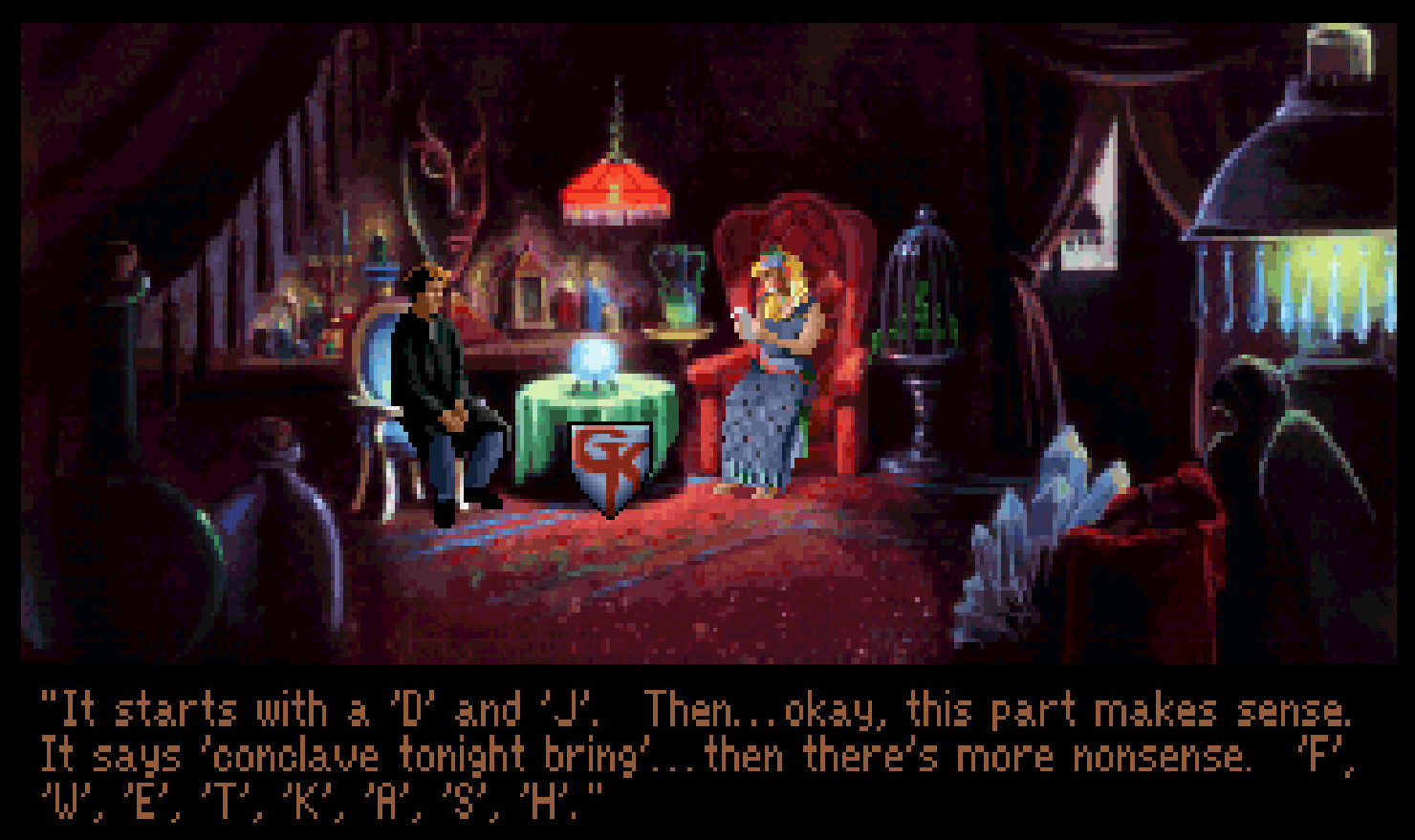

Cut scenes like this one may reveal important clues to the game’s puzzles. (Credit: Sierra On-Line. Fair use.)

Driven by story and dialogue

There are some important ways in which Gabriel Knight sets itself apart from many other games of its era:

-

The game has a narrator, voiced by Virginia Capers with a thick accent, who often inserts her own commentary about Gabriel’s (attempted) actions, and seems to take some delight in his misfortunes.

While other Sierra games have featured narrators, Capers gives the game a unique personality when, for example, she bursts into laughter as you examine an item in Gabriel’s inventory that relates to a near-death experience. -

Dialogue is a central part of the gameplay. There are separate “talk” and “ask” actions. When you talk to a character, Gabriel will usually cycle through a few casual remarks; when you ask them questions, the game switches to a focused dialogue interface in which you can choose subjects to discuss.

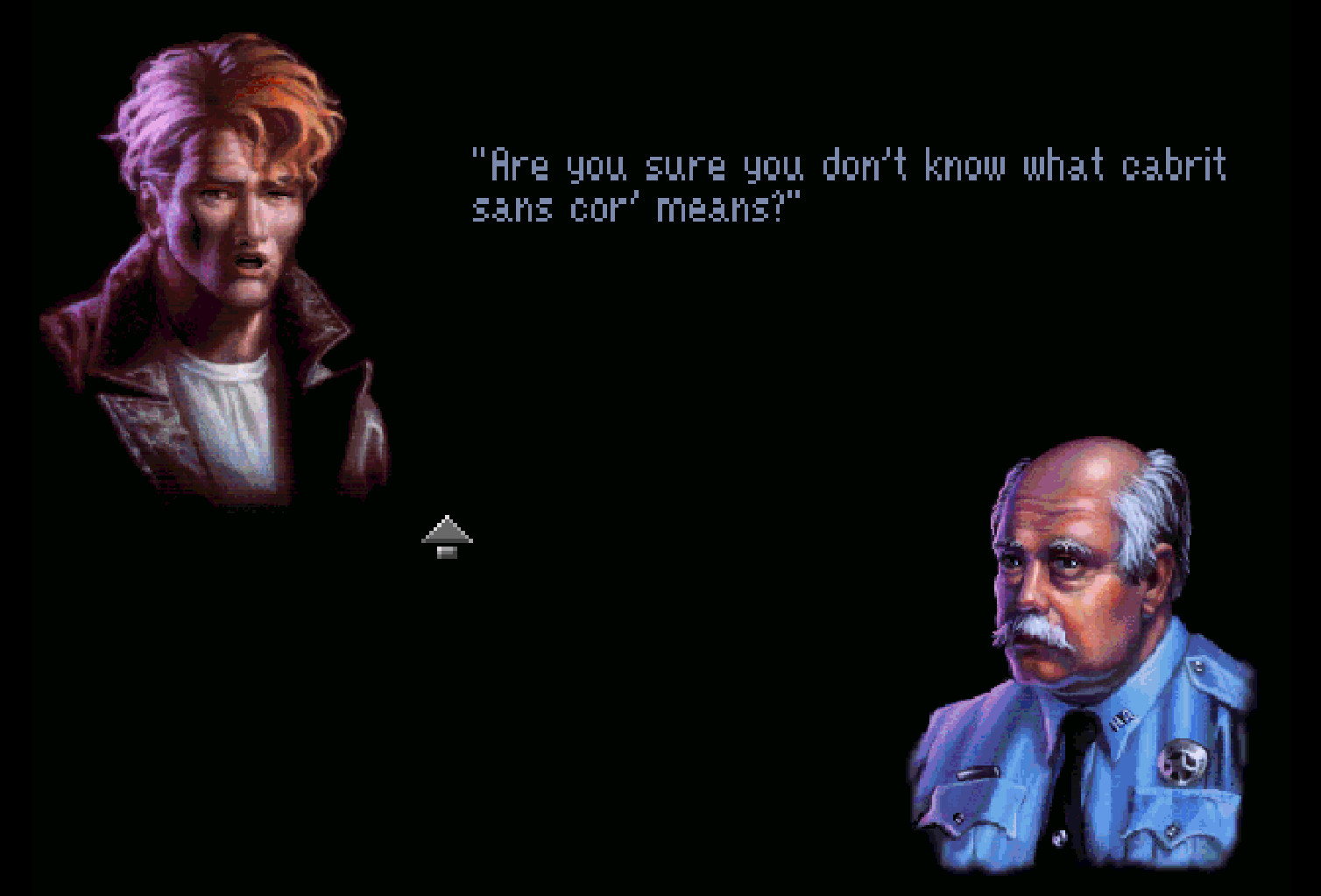

Although the dialogue tree grows to a somewhat ridiculous length (you can literally ask anyone you come across what they know about the voodoo murders, or whether they know the meaning of “cabrit sans cor”), the dialogue system is a nice departure from the usually very limiting conversational options of adventure games. -

The plot advances over the course of 10 days, and the locations and possible interactions change over time. As you visit the police station on different days, for example, you will learn about how the case has progressed since you last spoke to detective Mosely.

The game’s sense of time is entirely tied to specific actions of your character. It’s only when you have solved certain puzzles, or asked certain questions, that you can move on to the next day. This can be frustrating, as only the game knows what specific thing you have to do to unblock the flow of time.

Gabriel Knight was one of the first adventure games to utilize higher resolution SVGA graphics, but it did so only in a limited fashion, such as in the dialogue interface. (Credit: Sierra On-Line. Fair use.)

A product of its time

It is a game of its era, something you may be reminded of when you realize that Gabriel can only use landline phones to communicate over long distances. It’s also reflected in the gameplay: To solve many puzzles, it’s advisable to pay careful attention to every line of dialogue.

Adventure games from this time were meant to keep you playing for many, many hours—if you still got stuck, the expensive hint line was waiting to take your call. This being a Sierra game, you can very much die (especially in the second half), so saving the game often is a good idea.

The racial politics of Gabriel Knight are more troubling. While the story incorporates historical facts about Louisiana Voodoo, the increasingly preposterous narrative follows an all too familiar trajectory in which a white hero (Knight) must overcome forces of evil, who happen to be people of color. That it wraps both heroes and villains in a thin veil of moral ambiguity hardly makes this more palatable.

In spite of these flaws, Gabriel Knight deserves recognition as a milestone in video game storytelling techniques, and is still enjoyable to play today. I recommend using the Universal Hint System over a walkthrough, as it will give you more opportunities to discover solutions to puzzles on your own. The soundtrack has held up well, and adds to the game’s atmosphere and character.

A 20th anniversary remake with new graphics—and a wholly different voice cast—was released in 2014. While Gabriel Knight deserves its place in video game history, I’m not sure it needed a remake. There are new stories to tell, and new heroes to play—ones that challenge stereotypes rather than reinforcing them.