Review: How to Hide an Empire

In How to Hide an Empire, historian Daniel Immerwahr argues that we know far too little about the history of United States beyond the contiguous states that make up the “logo map”:

As in the example above, representations of the United States often exclude Hawai’i and Alaska, to say nothing of “territories” like Puerto Rico, American Samoa, Guam, the US Virgin Islands, or the Northern Marianas. But the stories of the millions of people who live there deserve to be heard, and Immerwahr does his best to tell them.

To set the stage, Immerwahr describes the expansion of the United States from coast to coast, and the broken promises and systematic removal of native tribes that came with it. Whether tribes sought to assimilate or to fight, their land was taken; projects like the creation of the State of Sequoyah failed. Instead, US states borrowed the names of native tribes whose land was stolen to create them.

The story continues with America’s quest for bird poop—the annexation of island territory to harvest accumulated guano—and culminates in a America’s colonialism binge at the dawn of the 20th century. In the Spanish-American War, America notably “acquired” the Philippines, Guam, and Puerto Rico. The Philippine-American War that followed—a war in which Filipinos fought for liberation from American colonial rule—caused a civilian death toll in the hundreds of thousands.

The Cancer Man

But the Philippines are not the only country that resisted American colonialism. From the beginning, many Puerto Ricans have favored independence, especially in light of the overt racism they encountered in contact with visitors from the US mainland.

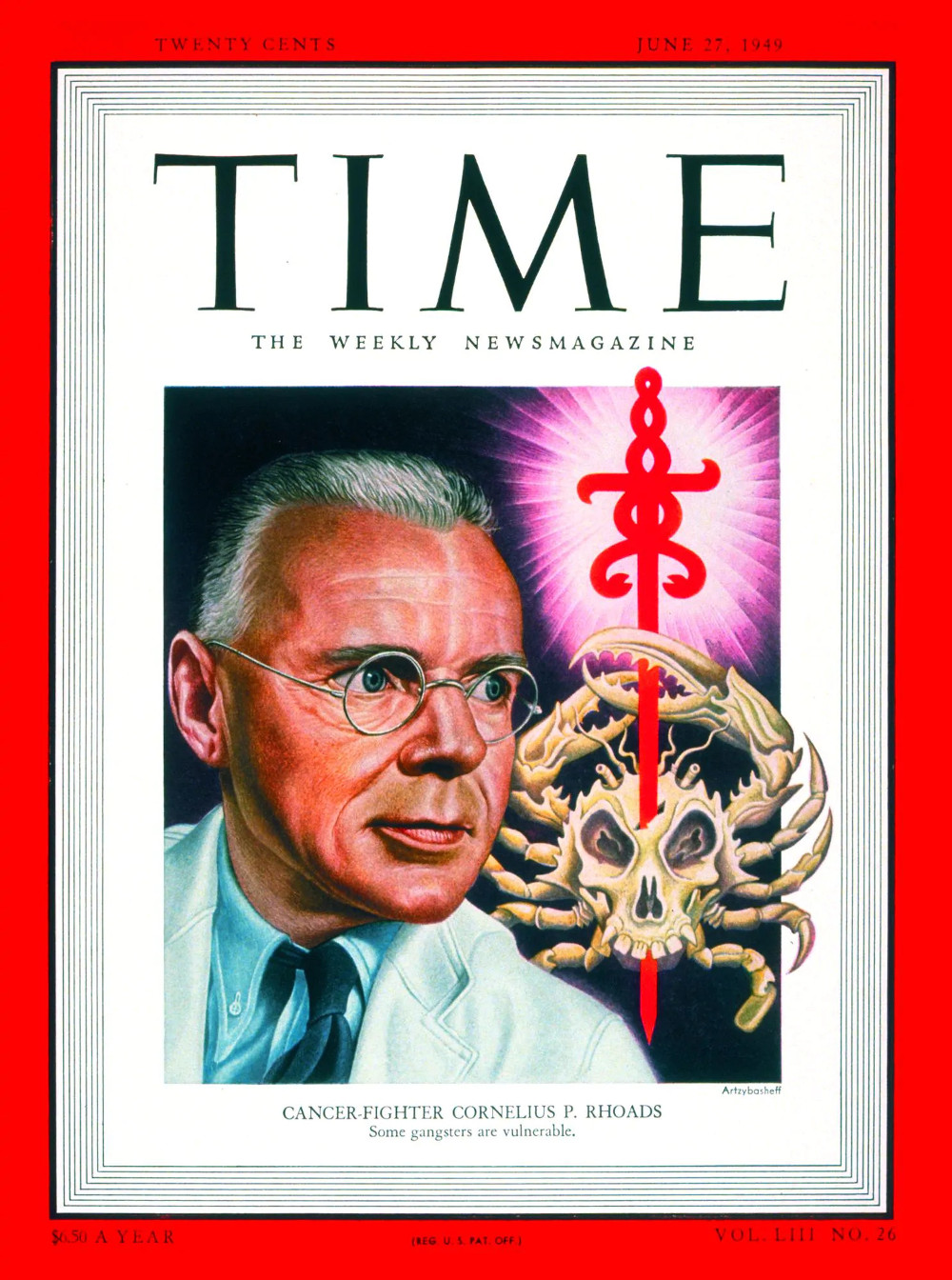

Immerwahr tells the story of Cornelius Rhoads, a US mainland pathologist who visited Puerto Rico as part of an international health effort. Rhoads not only harbored deep racial hatred for the Puerto Ricans, he bragged about murdering them:

They are even lower than Italians. What the island needs is not public health work but a tidal wave or something to totally exterminate the population. It might then be livable. I have done my best to further the process of extermination by killing off 8 and transplanting cancer into several more.

No evidence of these crimes was ever found (which does not mean that they did not take place), and Rhoads called the letter a joke. He faced no significant consequences for it, and became a celebrated cancer researcher (and an expert in chemical and biological weapons, charged with approving tests on human subjects during the war).

Time Magazine cover featuring Cornelius Rhoads, June 27, 1949. (Credit: Time Magazine. Fair use.)

The Rhoads letter was a major scandal in Puerto Rico that drove many to join its burgeoning independence movement. One of them was Oscar Collazo, who joined with another Puerto Rican nationalist in an attempt to assassinate US President Harry Truman in 1950.

Due to the historical amnesia that characterizes America’s relationship with its “territories”, it was only in 2002 that Rhoads’ name was removed from a prestigious award due to the letter in which he bragged about murdering Puerto Ricans. “And that’s how you hide an empire”, Immerwahr observes.

The Empire of Points

The later part of the book mainly deals with the question why America did not become an empire in the British mold after World War II. Instead, the US relinquished control over one colony (the Philippines, through the Treaty of Manila) and sought to establish no new colonies elsewhere. Military bases around the world—a “pointillist empire”—replaced the conventional model of control over vast swaths of territory.

Immerwahr sees multiple reasons for this change, most notably:

-

the growing rise of independence movements around the world, which made colonies an increasingly costly proposition;

-

America’s leadership in synthetics, logistics, and standardization—achieved in significant part through wartime efforts—which enabled it to project military and economic power throughout the world, without being dependent on territorial control;

-

wartime weariness of US troops, who wanted to go home, not occupy a country like the Philippines they had fought side-by-side with the Filipinos to defend.

Immerwahr concludes by examining the political and cultural impact of US military bases, and the connection between this new form of imperial power and the threat of terrorism organized from many small, well-hidden locations.

The Verdict

Immerwahr is a very talented writer, and How to Hide an Empire is full of facts about the “Greater United States” most readers are unlikely to be familiar with. While this isn’t a funny book, Immerwahr isn’t shy to use humor and the first person intermittently throughout the book, without it seeming out of place.

All of this is a potent combination, and I found the book to be a real page-turner. My only criticism is that the author, in emphasizing the role of territory (from colonies to military bases), ends up spending very little time discussing the many other ways the US has projected imperial power, from overthrowing governments to meddling in elections.

While I don’t believe for a moment that this was the author’s intent, readers unfamiliar with this larger history might come away with the impression that the territorial story is the whole story. A larger analytical frame would have served the book well, but as it is, it remains a very readable and insightful analysis of America’s relations with the people who live in the United States beyond the logo map.