Review: Dinner with Darwin

Jonathan Silvertown is Professor of Evolutionary Ecology at the University of Edinburgh in the United Kingdom, and a prolific author. His latest book, Dinner with Darwin, provides a highly compressed summary of what evolutionary biology can tell us about our food, from the domestication of plants and animals to how we unknowingly harnessed complex microbiology when we learned how to make cheese, wine and beer.

The book is more meticulously researched than most popular science books; the extensive end notes provide many references to recent scientific papers. But it maintains a lighthearted tone throughout, beginning with an imaginary reunion dinner with our hominin ancestors. This narrative device leads us to an exploration of different food groups like fish, bread, meat, vegetables, desserts, and alcohol.

In each of these contexts, we are served morsels of knowledge: about how wheat’s massive genome (much larger than our own!) has allowed it to adapt to many different climates; about why our sense of smell is crucial to our ability to discern flavors; about how our ape-like ancestors’ acquired ability to eat rotten fruit set the stage for humanity’s roller-coaster relationship with alcohol.

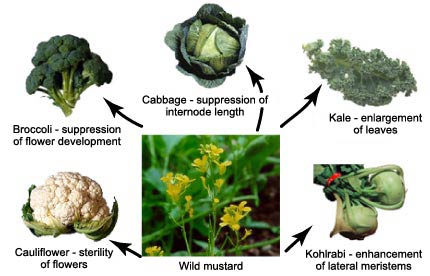

There are many visually powerful ways to explain the impact of artificial selection, such as this illustration of wild mustard selection from the University of Berkeley’s Evolution Library. Unfortunately, “Dinner with Darwin” lacks visual explanations, aside from a few (useful) maps.

The book ends with a brief discussion of the future of food, including a vigorous defense of genetic engineering to support the survival of our ever-growing population in the face of climate change. In this brief chapter, Silvertown doesn’t touch on topics like biological patents and biodiversity, and in this respect, his argument feels a bit unfair to critics of agri-corporations who have more nuanced pro-science perspectives (e.g., critiques of biopiracy and of patentability per se).

The acknowledgments begin on page 197, making the book a quick and pleasurable read that may leave you hungry for more. There are six maps, but no photos or illustrations, which is a bit of a missed opportunity—whether the author is discussing the artificial selection of plants towards non-shattering seed heads, or the hybridization of yeast strains to achieve properties such as cold resistance, there are many occasions where visual explanations would have helped.

Regardless, you are almost certain to learn something new in each chapter. The book, then, is more of a starter course: after reading it, you may want to dive deeper into topics like artificial selection, re-examine your gardening practices from an evolutionary perspective, or start your own alcohol experiments (of the highly scientific variety, of course). 4 out of 5 stars.