Review: 13th

As a German who has now been living in the US for eight years, my perspective on racism in this country is colored by what I learned from an early age about my own country’s history: about the Nuremberg race laws, the Kristallnacht, the Warsaw Ghetto, the mass killings by Einsatzgruppen, and ultimately the Holocaust – the organized mass-murder of six million human beings.

As children, we would learn about these facts about our country not just through textbooks, but also through organized viewings of films like Schindler’s List, school exhibits, visits to museums, and even visits to the concentration camps themselves. At times, fatigue would set in: this was not something we had been involved in, or even our parents. Why must we keep talking about it?

But then, in the early 1990s, Germany experienced a wave of neo-nazi attacks on foreigners and asylum seekers. And it was then – I was 13, 14 years old – that I realized that there had in fact been a deep civic purpose in studying this history.

I moved to the US in the year Barack Obama was elected President, and the feeling that a very old divide was finally being healed was palpable. Americans could celebrate themselves as good people who had elected an African-American with the middle name “Hussein” and a last name that sounded like “Osama”, ignoring race and embracing a positive, optimistic message of “hope and change”.

The cancer of racism

But white voters did not vote for Barack Obama. 55% of them voted for John McCain. And we know about the ugly conspiracy theories around Barack Obama’s place of birth and religion, and various attempts to smear him as a dangerous radical who fraternizes with terrorists. This revealed another side of America, the ugliness that many thought we would be able to leave behind. The cancer of racism.

Ava Marie DuVernay is no stranger to fighting this cancer. In 2014, she directed Selma, a beautiful historical drama based on a pivotal moment in the struggle of African-Americans to have their say at the ballot box, a struggle which continues to this day.

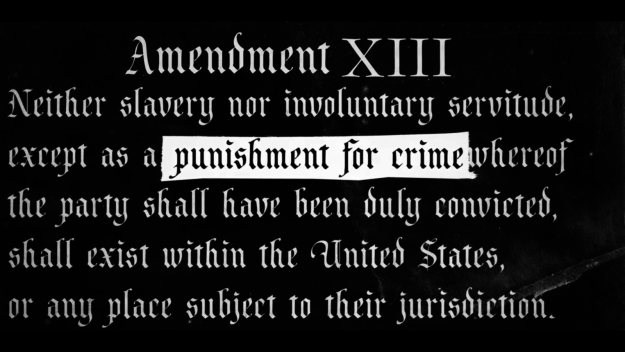

Her new documentary, 13th, is available on Netflix. The title refers to the 13th amendment to the US constitution which abolished slavery, but permitted forced labor in prisons.

13th calls this a loophole, and notes that it was quickly exploited to arrest freed slaves for “loitering” or “vagrancy” and then force them to work on rebuilding America after the Civil War. It chronicles the history of racism in the United States since then, including the FBI’s campaign to destroy efforts by African-Americans to build a social movement for equal rights. It then describes Richard Nixon’s “Law and Order” presidential campaign, and offers a recently surfaced quote by Nixon advisor John Ehrlichman which deserves being quoted here in its entirety:

“The Nixon campaign in 1968, and the Nixon White House after that, had two enemies: the antiwar left and black people. You understand what I’m saying? We knew we couldn’t make it illegal to be either against the war or black, but by getting the public to associate the hippies with marijuana and blacks with heroin, and then criminalizing both heavily, we could disrupt those communities. We could arrest their leaders, raid their homes, break up their meetings, and vilify them night after night on the evening news. Did we know we were lying about the drugs? Of course we did.”

Criminal injustice

13th goes on to describe the effects of disparate sentencing (e.g., with African-American crack cocaine users being sentenced far more harshly than white cocaine users), and the explosion of the US prison population under the “tough on crime” policies of Reagan, Bush and Clinton. It describes the rise of the prison industry, and the activities of the shady American Legislative Exchange Council in promoting “Stand Your Ground” laws and private prisons.

The film does not spend a lot of time on the “forced labor” aspect, explaining only briefly which industries rely on it. In general, aside from prison population numbers (including the horrifying racial divide of the prison population), this is a film that is more about politics and history than about statistics and data. It cannot entirely escape the gravity of the US presidential election, and it powerfully ties Trump’s racist campaign and the struggle of the Black Lives Matter movement back to images of hate and violence directed against African-Americans in the 1960s.

The documentary doesn’t have a strong authorial voice; instead it uses rap music with text overlays to create emotional breaks in the story. While it starts and ends strongly, it at times “loses the thread”, throwing too many facts at the viewer, “building awareness” at the cost of being less effective. Ultimately, however, its core message comes through very clearly: racism is a cancer that adapts to its environment, and to defeat it, we must understand this process of adaptation.

13th warns of a future after mass incarceration which The Daily Beast referred to as “Ankle Bracelet America”, where individual surveillance and enslavement of prisoners outside prisons could take the place of criminal justice reform, creating (again) merely the illusion of real progress.

At 100 minutes with many emotional scenes (tears started to well up in my eyes several times), this isn’t an easy documentary to watch. But if this election season is teaching us anything, it’s that the cancer of racism in the United States is alive and well. To defeat it, we must learn how it adapts and metastasizes. Ava Duvernay’s 13th is an important contribution to that understanding, and I do recommend it.