Review: The Boy in the Book

The Boy in the Book is a web-based full-motion video game; the website describes it as ”an interactive true story in 10 chapters”. It is free without any strings attached, and has also been published in book form and performed as a live show.

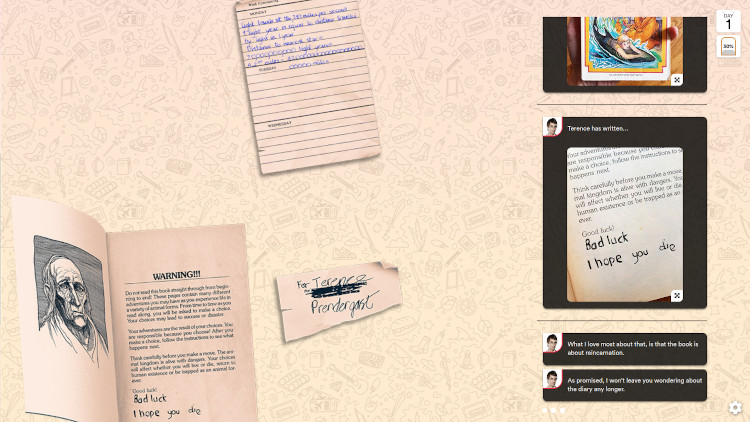

The game/documentary is premised on the random discovery of pages from an old diary in a stack of Choose Your Own Adventure books bought on eBay. In almost stenographic shorthand, the diary pages record the author’s experiences with bullying, with their attempts to overcome extreme shyness, and even suicidal thoughts.

The notes suggest that the diary’s author, a boy named Terence Prendergast, was born in 1975. Is he alive, and if so, what happened to him since he wrote the diary?

Choices in the chatroom

The buyer of the books, a Welsh writer and performer named Nathan Penlington, sets out to discover and document the story of the “boy in the book” together with his friends Fernando, Sam, Nick—and with you, the player.

You interact with Nathan & friends through an instant message chatroom in which the group discusses what to do: which leads to pursue to locate the author of the diary, which detours to take along the way, and whether to persist in what increasingly seems like a futile quest.

As the player, you are presented with dialog options throughout the chat, which sometimes represent important forks in the road. Depending on your choices, different responses, videos and images appear in the chatroom. They are grounded in the same reality (e.g., the same interviews), but put the focus on different narrative paths.

The events of the game play out in a chatroom with Nathan and his friends. Like in a “Choose Your Own Adventure” book, you get to make choices about how their effort to document the story of “the boy in the book” unfolds. (Credit: https://www.theboyinthebook.co.uk/. Fair use.)

Abort, abort, abort?

You can rewind your choices and take as many different paths as you like, and the game auto-saves in your browser (if you don’t play it in private browsing mode).

To underscore that these choices are meaningful, Nathan asks you in the first chapter whether he should pursue his obsession with the diary at all. If you tell him not to, the story comes to a quick end and the credits roll.

Nathan’s question is a fair one. The ethics of the whole undertaking can sometimes feel uncomfortable, since the found diary pages are presented as the writings of a private individual. As you play through the story, it becomes clear that everyone is appearing on screen willingly.

The Verdict

While the story feels a bit padded out in the way many documentaries are, I still found it was ultimately beautifully done and well worth my time. I watched two of the main endings and was moved by both of them. In total, I spent about two hours with The Boy in the Book.

The game features gorgeous illustrations and a fitting soundtrack. Overall, I found that the web-based format worked surprisingly well, with two exceptions: 1) The rewind feature didn’t always work for me (text was sometimes repeated or did not appear until I reloaded), 2) the game’s music kept playing even during videos which had their own music in them, which was a bit distracting.

The individual chapters are quite short. I would recommend giving the first one a try. If you find Nathan in particular offputting at all, you’re not going to enjoy The Boy in the Book—he’s on screen a lot. But if you like his style, and if you share at least some appreciation for Choose Your Own Adventure books, you’re likely to have a good time.