Review: Overthrow

How much do you know about the overthrow of the Kingdom of Hawaii, about the Philippine-American War, about America’s efforts to depose José Zelaya in Nicaragua, Jacobo Árbenz in Guatemala, Mohammed Mossadegh in Iran, and Ngo Dinh Diem in South Vietnam? If the answer is “very little”, Stephen Kinzer’s 2006 book Overthrow remains a reasonable introduction to these and other “regime change” efforts.

Kinzer, a journalist and writer who was the New York Times correspondent for Central America in the 1980s, weaves a narrative of some of America’s military and intelligence interventions in other countries from the late 19th century to the early 21st. He connects the political events with the stories of some of the key figures involved, like Henry Cabot Lodge and his grandson, Theodore Roosevelt, and the Dulles brothers—John and Allen, subject of another book by Kinzer.

Throughout his analysis, Kinzer points at the clear commercial interests at the root of foreign policy interventions: taking control of Hawaii at the request of American-born plantation owners, preserving United Fruit’s corporate stranglehold over Guatemala, punishing Iran’s Mossadegh for attempting to end foreign exploitation of the country’s oil reserves.

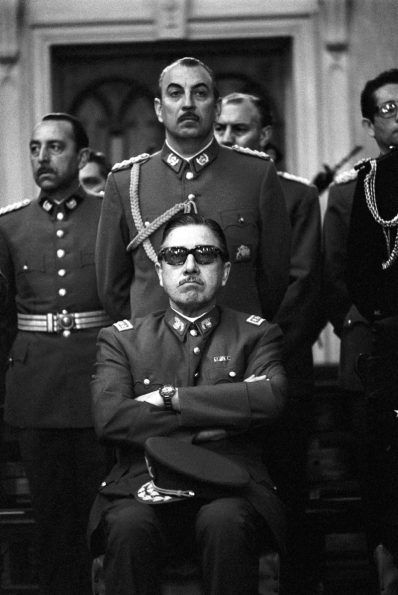

After a directive from Richard Nixon to “make the economy scream” through sabotage, the CIA used the subsequent instability to help install Augusto Pinochet, replacing Chile’s democratically elected leader, Salvador Allende. Pinochet’s regime was responsible for the death of thousands, and for the arrest and torture of tens of thousands. (Credit: Chas Gerretsen. Fair use.)

The typical pattern of each chapter is “storytelling → larger political events → analysis”. As a storyteller, Kinzer is not quite at the level of Erik Larson—there are some slightly jarring repetitions, for example—but the book is certainly engaging.

The book’s value is ultimately limited by its narrow scope, and by its unwillingness to stray too far outside the Overton window of American political discourse. For example, America’s many efforts to influence democratic elections in other countries help to understand why democracy and political independence are often difficult to reconcile for smaller countries.

But these efforts, far more numerous than direct intervention, are largely out of scope, as are many of the other methods America’s military and intelligence apparatus have employed (and continue to employ) to bolster friendly regimes, however brutal, and to undermine perceived unfriendly ones.

When Kinzer imagines “what-ifs” for countries like Guatemala and Nicaragua, he theorizes that America stunted the emergence of independent capitalist democracies. In full cognition of the historical facts, it should not take much daring to speculate whether democracy and capitalism are in fact compatible at all.

The book’s narrative ends with the near-term effects of George W. Bush’s war in Afghanistan and Iraq. Kinzer’s 2006 prognosis for both countries was not optimistic; today, one would have to connect the dots between these interventions, subsequent American and European actions in the region, and the terror, wars and instability that continue to this day.

I recommend Kinzer’s book with the above reservations as a starting point to explore America’s imperialist history. It may also serve as a cautious introduction for readers wary of more radical authors like Chomsky (who eloquently critiqued Kinzer’s New York Times reports from Central America in the 1980s). 3.5 of 5 stars, rounded up because of the importance of the subject and the quality of the writing.