Review: ProPublica

ProPublica has become almost synonymous with a new nonprofit approach to investigative journalism. There are three major reasons for this:

- It was born digital in 2007 (unlike veteran organizations like the Center for Investigative Reporting, which has been around since 1977).

- It received $10M of seed funding and continued support from liberal billionaires Herb and Marion Sandler, instantly making it one of the most well-funded journalism nonprofits.

- It was the first online news source to receive the prestigious Pulitzer Prize, and has since received two more Pulitzers, and many other awards.

Positioning

Propublica describes its mission as follows:

To expose abuses of power and betrayals of the public trust by government, business, and other institutions, using the moral force of investigative journalism to spur reform through the sustained spotlighting of wrongdoing.

It claims to take no sides:

We do this in an entirely non-partisan and non-ideological manner, adhering to the strictest standards of journalistic impartiality.

ProPublica’s focus is primarily on the United States. Beyond that single constraint, its mission gives it a very broad mandate.

Financial Origins

As noted above, the project would not exist without the Sandlers. Herb and his late wife Marion made their money with Golden West Financial, which they purchased in 1963 and sold in 2006 to Wachovia, reportedly making $2.4B from the sale. They dedicated $1.3B to the Sandler Foundation, which has so far given $750M to many causes ranging from political (John Podesta’s Center for American Progress) over human rights (Human Rights Watch) and environment (Beyond Coal) to science/medicine (UCSF Sandler Neurosciences Center).

The role of Golden West, which also operated under the name World Savings Bank, in the 2007-2008 financial crisis is a subject of considerable dispute. Unsurprisingly, right-wing critics who seek to discredit ProPublica refer back to this history, such as this detailed, characteristically conspiratorial analysis by Glenn Beck’s The Blaze.

What’s clear is that Golden West was a portfolio lender, meaning it didn’t engage in the selling and re-selling of debt under cryptic names such as “collateralized debt obligations”. Many experts view this “securitization of loans”, and the false positive ratings obtained from rating agencies, as central to the financial crisis (an interpretation popularized by the movie “The Big Short” based on Michael Lewis’ book of the same name).

In the heat of the crisis, the practices of GW/WS did come under intense media scrutiny, especially given the sale of the company to Wachovia – which subsequently underwent a government-forced sale to Wells Fargo in 2008. The article “The Education of Herb And Marion Sandler” by the Columbia Journalism Review is an in-depth summary, which concludes that some of the criticism of the Sandlers was unfair and overwrought (Saturday Night Live revised a skit that called the Sandlers “people who should be shot”). The CJR article also recapitulates evidence that some mortgage brokers employed by GW/WS did employ unethical sales practices.

Nonetheless, the Sandlers were long-time advocates for ethics and integrity within the banking industry, and in fact founded the Center for Responsible Lending in 2002, which has been a strong advocate for regulatory reform, including for the creation of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau.

In short, a review of the evidence suggests that it is unfair to paint the Sandlers as villains of the crisis, or to make any a priori assumptions about bias in ProPublica’s reporting based on their philanthropic support for the project.

Early History and Executive Compenstion

ProPublica is based in New York City. Herb Sandler was the first Chair of the Board (he is now a regular trustee). Its founding editor, Paul Steiger, was previously managing editor of the center-right Wall Street Journal, which was acquired by Rupert Murdoch’s News Corporation after Steiger’s departure. Given the Sandlers’ support for progressive causes, the hire may have been intended to send a strong signal that ProPublica would be impartial and not an activist project.

Steiger’s initial compensation by ProPublica was $570K (plus $14K in other compensation such as insurance), as a Reuters blog reported under the sardonic headline “Philanthrocrat of the Day”. Outside public broadcasting, this is easily the highest executive compensation among any of the nonprofit publications we’ve reviewed.

In 2015, the year of the most recent available tax return, Steiger was Executive Chairman (a part-time role) and received $214K. President Richard Tofel received a total of $421K, Editor-in-Chief Stephen Engelberg received $430K, while a senior editor typically received $230K in total comp.

This is still high compensation, especially for the two top jobs. For comparison, in the same year, the CEO of Mother Jones (a San Francisco based journalism nonprofit with comparable revenue) received total comp of $195K, while DC bureau chief David Corn received total comp of $175K.

Why does this matter? Executive compensation ultimately speaks to the organization’s use of donor money (more money for executives means less money for journalists), as well as to the hiring pool it considers for key positions. Above-sector compensation may predispose it to seeking top hires from for-profit media, as opposed to building internal and sector-specific career paths.

It is difficult for organizations to change established compensation practices, but as we will see, ProPublica is relying more and more on public support, so it is reasonable to ask questions about these longstanding practices.

Transparency, Revenue

Compared with many other organizations we have reviewed, ProPublica’s level of transparency is excellent. (There’s no strong relationship to compensation or revenue: We have found very small organizations that are great at this, and very large ones that are terrible.)

ProPublica has published 7 Annual Reports and 14 shorter “Reports to Stakeholders” about its work. Its 2016 report was published in February 2017, which is very timely. The organization also makes its tax returns and financial statements easy to find.

For 2016, ProPublica reported $17.2M in revenue, of which most came from major gifts and grants ($9M/52.5% from major gifts/grants of $50K or more, and an additional $3.7M/21.8% from Board members).

$2.1M/12.5% came from online donations. That seems like a small share, but it’s a massive increase compared to the previous year, when ProPublica reported only $291K in online donations.

This bump in donations is, of course, due to the election of Donald Trump, which led to a surge of donations to many nonprofit media – aided, in ProPublica’s case, by a shoutout on John Oliver’s news/comedy program Last Week Tonight.

Measuring Impact

ProPublica’s reports have always focused on trying to make the connection between its reporting and real-world impact. The impact page captures the highlights from these reports.

On the positive side, it is highly laudable that the organization makes efforts to monitor long term consequences. For example, in its 2016 report, it notes:

A 2010 ProPublica investigation covered two Texas-based home mortgage companies, formerly known as Allied Home Mortgage Capital Corp. and Allied Home Mortgage Corp, that issued improper and risky home loans that later defaulted. Borrowers said they’d been lied to by Allied employees, who in some cases had siphoned loan proceeds for personal gain. In December a federal jury ordered the companies and their chief executive to pay nearly $93 million for defrauding the government through these corrupt practices.

Monitoring what happens after a story is published, following up repeatedly, is a big part of what characterizes excellent investigative journalism.

On the negative side, the impact reports are almost unreadable – they’re long bullet point lists without any meaningful structure or even links to the articles they reference, and without a larger narrative to connect them.

In 2013, ProPublica published a whitepaper called “Issues Around Impact” that describes robust internal tracking processes. For example:

ProPublica makes use of multiple internal and external reports in charting possible impact. The most significant of these is an internal document called the Tracking Report, which is updated daily (through 2012 by the general manager) and circulated (to top management and the Board chairman) monthly.

The whitepaper includes some samples of these tracking spreadsheets, but they are generally not made public. Is that the right call? I don’t know, but I do think that it’s worth thinking about ways to make the overall ongoing impact monitoring more public and more engaging.

Content Example: “Machine Bias”

Machine Bias is a good example for how ProPublica tackles large investigations. Major topics are organized in series, and the Machine Bias series comprises 25 posts ranging from major stories to brief updates. The series examines the increasing role algorithms play in society, from online advertising networks to the criminal justice system.

It’s a complex topic, and the first major article in the series, also titled “Machine Bias” and published in May 2016, is no exception. It focuses on software developed by Northpointe (recently re-branded Equivant) which aids judges in assessing the likelihood that a given criminal offender will commit crimes again when released into the general population.

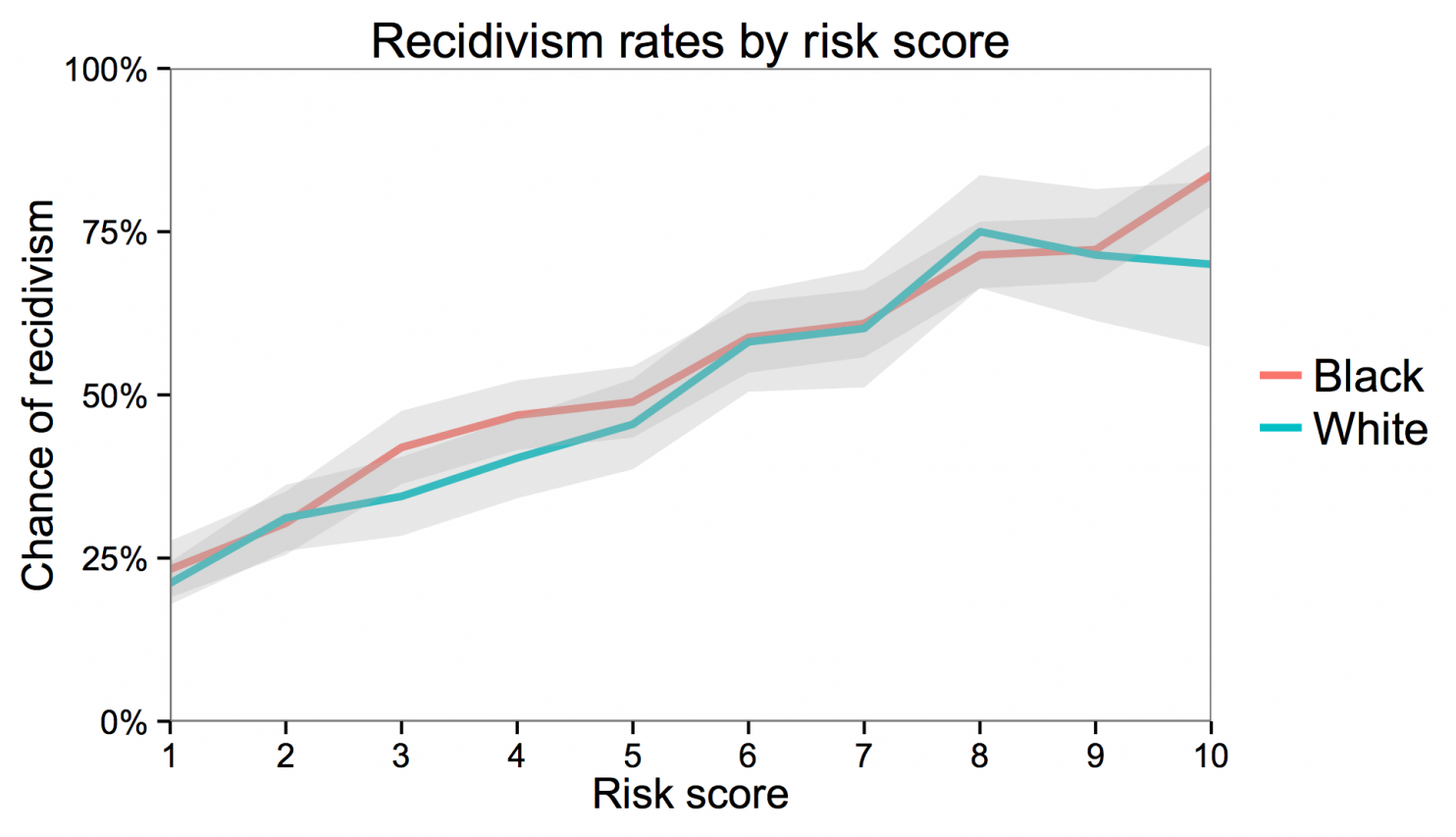

These risk assessments may end up influencing everything from sentencing to parole conditions, even though the system is not meant to be used in sentencing. ProPublica asserts that the system is biased against black defendants. According to its findings, the rate of false positives (% of non-re-offenders who were falsely labeled higher risk) is nearly twice as high for black defendants as for white ones (44.9% for blacks vs. 23.5% for whites), while for white defendants, the rate of false negatives (% of re-offenders who were falsely labeled low risk) is much higher (47.7% for whites vs. 28.0% for blacks).

The company behind the tool strongly disputed the findings. ProPublica published several follow-ups, including a detailed technical response to Northpointe’s criticism. Ultimately, as a Washington Post follow-up blog post by a team of researchers explained well, much of the disagreement boils down to your definition of fairness.

In the study’s sample, African-Americans have a higher recidivism rate (likelihood to commit another crime after being arrested). That means that even if the algorithm is “equally accurate” at predicting recidivism, it will be wrong for a larger absolute number of African-Americans, and therefore for a larger share of the total number of African-American offenders. From an individual African-American’s perspective, you’re more likely to be falsely flagged as high-risk than a white person.

The analysis by a team of independent researchers summarized in a Washington Post blog shows that both Northpointe and ProPublica have a point. A risk assessment can have comparable predictive value between racial groups, but have disparate (unfair) impact on one of them.

Evaluating ProPublica’s article

ProPublica’s article sheds light on a phenomenon known as disparate impact. More black people than white people receive unfair treatment through many systems or policies, such as Northpointe’s risk assessment tools, because of long-standing population-level differences in arrest rates, poverty, economic access, and so on. This feeds a vicious cycle that limits opportunities and exacerbates racial stereotypes.

The Northpointe algorithm is based on a questionnaire that includes questions such as “How many of your friends/acquaintances have ever been arrested?”. Regardless of its predictive value, this is the type of question that contributes to racially disparate impact: According to the Sentencing Project, the likelihood for white men to be imprisoned within their lifetime is 1 in 17, and for black men it is 1 in 3.

It should be noted that ProPublica argues in its analysis that the algorithm’s bias extends beyond the base rate difference. In its technical notes, it states that “even when controlling for prior crimes, future recidivism, age, and gender, black defendants were 77 percent more likely to be assigned higher risk scores [for violent recidivism] than white defendants.” If true, this speaks to persistent bias beyond what would be expected of an “equally accurate” algorithm.

ProPublica does not attempt to compare the accuracy and fairness of Northpointe’s approach with any other risk assessment method, automated or not. Obviously, to judge whether the system should be used and improved or abandoned, that’s a very important question. But ProPublica makes no assertions beyond the system’s disparate impact and does not sensationalize its findings. Northpointe may feel that it is being unfairly singled out, but demonstrating problems by way of specific examples is in the nature of investigations like this one.

The organization of the investigation into a series, with repeated follow-up and reasonable presentation of disagreement, speaks to tenacity and systematic thinking required to achieve meaningful change. The inherent complexity of the subject would pose a challenge to anyone; the original article makes noble efforts to penetrate the numbers with examples and storytelling, but in my opinion falls a little short in that regard.

In spite of these limitations, there is little doubt that the article has stimulated important debate, follow-up research, and even meaningful action. As ProPublica reported, Wisconsin’s Supreme Court ruled, citing ProPublica’s work, that warnings and instructions must be provided to judges looking at risk assessment scores. And a follow-up scientific investigation by Kleinberg, Mullainathan and Raghavan explained the fundamental mathematical tradeoffs in designing systems that are fair to populations with different characteristics.

ProPublica’s article is also a good example of what’s called data journalism. Beyond the ordinary qualifications of journalists, it relies on in-house statisticians and computer scientists to investigate a topic. This is not without its pitfalls, since such work does not pass through traditional scholarly peer review, while mistakes in stories like this one can be highly consequential.

ProPublica consulted with experts on the methodology and code used for its analysis. It made all internals of the analysis available, including through an interactive notebook on GitHub which anyone with statistical knowledge can use to replicate the findings. This shows a great level of care, though the sector as a whole might benefit from a more formalized review process when tackling data analysis of this complexity.

The “Machine Bias” series (which beyond the article reviewed here includes, e.g., an investigation into racial targeting of Facebook ads) received a Scripps Howard award.

Content Example: Investigating Trump, Obama

Since the election of Donald Trump, ProPublica has aligned more of its resources to cover the Trump Administration. In addition to a dedicated section, the writers and editors have prioritized several topic areas of increased public interest. These include hate crimes and extremism, health care, immigration, and influence peddling (per Trump’s campaign promise to “drain the swamp”).

Most of the Trump-related articles are shorter pieces such as “Trump’s Watered-Down Ethics Rules Let a Lobbyist Help Run an Agency He Lobbied”. In some cases, ProPublica calls on the public for help with its investigations. For example, it released a list of 400 Trump administration hires and invited public comment on them.

Given ProPublica’s claim of nonpartisanship, it’s worth asking if the site applied similar scrutiny to the Obama administration and the major policy themes of Obama’s two terms. Early in Obama’s first term, the site launched promise clocks to track Obama’s promises, though it’s unclear if the project was abandoned – for example, the promise clock to repeal the anti-gay “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” policy in the US military is still ticking, even though the policy was in fact repealed.

It investigated the use of stimulus funds in detail through an “Eye on the Stimulus” section, and dedicated a series to Obamacare and You, which tracked, among other subjects, the disastrous initial HealthCare.gov rollout, as well as problems with state-level exchanges. It also pursued in-depth investigations on promises such as Obama’s pledge to fight corporate concentration.

Whatever ProPublica’s blind spots, they don’t appear to be partisan. Its strength tends to be domestic reporting that touches ordinary people’s day-to-day concerns. In contrast, only a handful of articles cover topics such as the US arms industry and weapons sales to authoritarian regimes, or US involvement in Yemen’s bloody war. When major scandals break, such as Edward Snowden’s revelations about the NSA spying program, ProPublica does contribute its own coverage, but national security and foreign policy are clearly not its core expertise.

Newsletter, News Curation

Like most nonprofit media, ProPublica has an email newsletter. It’s pretty conventional and highlights the top stories of the day with brief abstracts. It includes some clearly labeled sponsored content.

A dedicated section called “Muckreads” is meant to highlight investigative stories from around the web. I say “meant to highlight” because it’s not been updated in recent weeks. The format also takes some getting used to: the page is simply a collection of tweets.

To its credit, ProPublica’s work over the years helped cultivate the #MuckReads hashtag on Twitter, but the project could use a kick in the behind or a reboot. Two counterexamples that may offer some inspiration:

- The newsletters of The Marshall Project (which focuses on criminal justice) do an excellent job of combining original and curated content in an engaging format.

- Corrupt AF is a recently launched site that curates stories related to (in the maintainer’s estimation) corruption in the Trump administration. It uses a similar “wall” format to Muckreads, but affords considerable space to excerpts and highlights.

Other Projects

ProPublica has a long history of starting projects that go beyond conventional journalism, including interactive databases and trackers. For example, its Surgeon Scorecard reveals complication rates about surgeons (an approach that’s not without its detractors).

It also maintains a database of nonprofit tax returns, and has taken over several projects from Sunlight Labs, after the Labs were shut down by the Sunlight Foundation, a pro-transparency organization. For example, ProPublica is now maintaining Politwoops, a database of deleted tweets by politicians.

The nerd blog logs new releases and updates to existing “news apps”, and code is generally published to ProPublica’s GitHub repositories. Still, with large databases like the Surgeon Scorecard, it would be useful to have clear commitments as to how frequently the data will be updated – or to officially mark them as unmaintained when that’s no longer the case.

ProPublica also asks for public involvement in many of its investigations, often by way of surveys (“Have you been affected by X? Tell us how”). An attempt to use Reddit to let users pitch story ideas has been abandoned.

Design, Licensing

ProPublica in 2008, 2011, and 2017. Its core site design has not changed significantly over the years.

ProPublica is nearly a decade old, and it shows. As I reviewed it, I encountered pages with broken layout, a page that threw an error message, pages that were prominently linked but inactive or abandoned, and old news apps that no longer worked as intended. It’s easy to get lost in the site’s fluctuating taxonomy of projects, tags, series, and investigations. The frontpage is cluttered with various buttons and boxes. The news feed on the front page combines internal blog posts (hiring announcements, awards, etc.) with major investigations.

It’s understandable that the site has shied away from major design reboots. There are a lot of moving pieces, and it would be easy to accidentally break older content. Still, site design and information architecture deserve more attention than they have received.

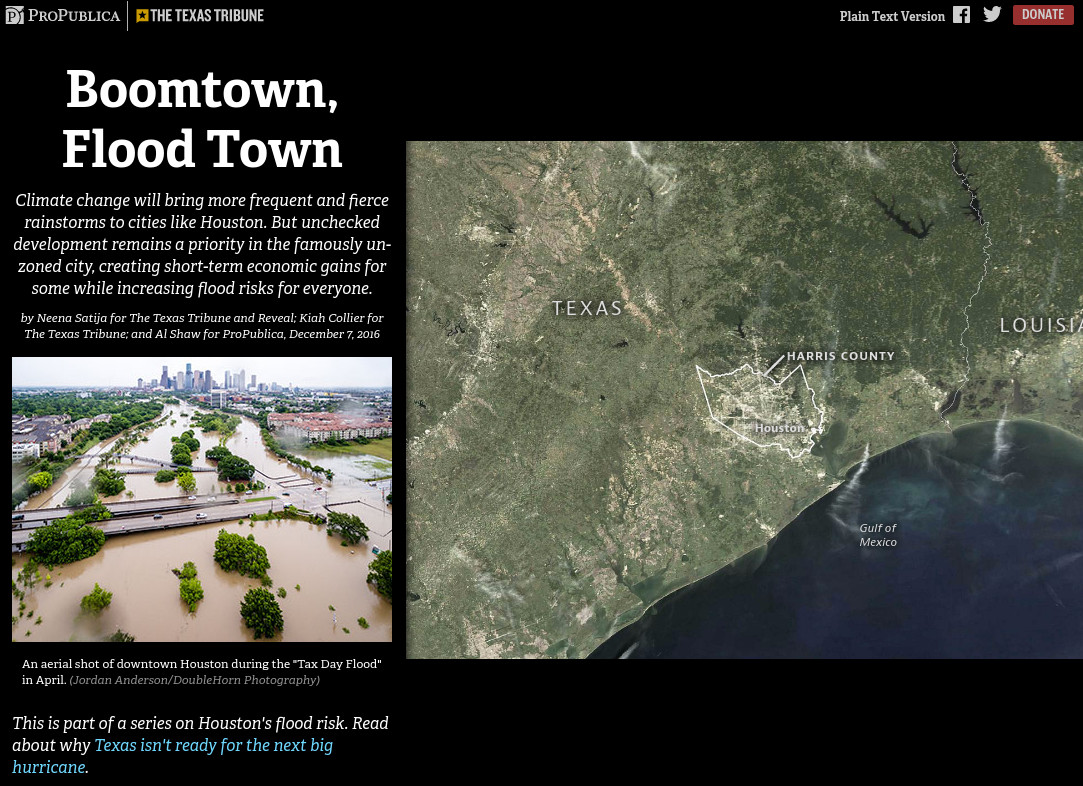

In fairness, individual stories sometimes get a lot of design love. Investigations like Boomtown, Flood Town are little micro-websites that are a joy to use (and that have deservedly won awards). Much of the site works well on mobile devices. In an age of ever-disappearing comment sections, it’s also nice to see that ProPublica hasn’t killed its own, and the signal-to-noise ratio of comments is not terrible.

It’s worth noting that many of ProPublica stories are jointly published in other traditional news media. Its content is also available under the Creative Commons Attribution/Non-Commercial/No-Derivatives license, which allows limited re-use. The consequence is that in spite of ProPublica itself not being to most engaging news destination, the impact of its stories is far greater.

Individual stories, such as “Boomtown, Flood Town”, somtimes have carefully built micro-sites. This one won a design award, as did several others.

The Verdict

Let’s break down the formal rating:

- Journalistic quality: ProPublica does excellent journalistic work and has been deservedly recognized for it. I’ve seen no evidence of manipulative intent; ProPublica may sometimes overstate its case a little bit, but generally follows up on criticism and posts updates and corrections.

- Executive compensation: ProPublica’s executive comp is well above average for the sector. Given its increasing reliance on small donations, it loses 0.5 points here.

- Wastefulness: There’s no significant evidence of waste, but a spring cleaning of abandoned or low-impact projects/services may free up some resources.

- Transparency: ProPublica’s organizational transparency is exemplary. Its approach to tracking and reporting impact is well thought-out, but could be more engaging and accessible.

- Reader engagement: In spite of some stellar story-specific design work, there’s definitely significant room for improvement when it comes to the main site’s design, discoverability of content, usefulness of the email newsletters, and technical maintenance of the site. ProPublica loses 0.5 points here.

Stepping away from the formal rating, ProPublica has published some remarkable investigations over the years which have positively impacted people’s lives. Its investigations have targeted large banks, airlines, state and federal government, hospitals, doctors, schools, nonprofits, and many others. As such it plays a vital watchdog role in US society.

I haven’t seen evidence that its funding sources drive its story selection, but this would be difficult to prove. Increasing the share of small donations is the best way to guarantee ProPublica’s independence, and it will require the aforementioned improvements in reader engagement.

ProPublica’s approach is least suited to addressing system-level failures: economic inequality, corporate tax evasion, climate change, mass incarceration, money in politics, LGBT discrimination, etc. That should not be held against it, as it is a somewhat inherent limitation of its mission. That’s where nonprofit media with a more specialized mission shine: InsideClimate News for climate change, The Marshall Project for mass incarceration, the Center for Public Integrity for money in politics, and so on.

The final rating is 4 out of 5 stars: recommended. You can follow ProPublica on social media (Twitter, Facebook), or via our Twitter list of quality nonprofit media.

(This review was rewritten in March 2017 to be brought in line with our review criteria. The score did not change.)