In case you missed it, the following reviews have been updated with lots more detail:

Team: Nonprofit Media

We look for quality sources of news and analysis in the public interest

Latest review

In November 2015, Nathan Robinson and Oren Nimni launched a Kickstarter to fund the creation of Current Affairs, a print magazine of “political analysis, satire, and entertainment” promising to “make life joyful again”. The campaign exceeded its goal of $10,000. Three years later, Current Affairs has become of the most reliably interesting and, indeed, enjoyable political publications on the left.

Print editions are issued every two months; each is carefully designed and, in addition to articles on diverse topics, every issue contains the creative works of many contributing artists. While many illustrations simply support a given article, in other cases it’s the illustrations that tell the story—see, for example, the “City of Dreams” illustration and accompanying article.

Recent Current Affairs covers. (Credit: Current Affairs. Fair use.)

Chances are that you’ve come across Current Affairs articles before through some of Nathan Robinson’s in-depth “takedown” articles about prominent American and Canadian political writers — especially those spreading reactionary ideas, e.g., Ben Shapiro, Charles Murray, Sam Harris, Jordan Peterson, Mike Cernovich, and Dinesh D’Souza.

Instead of simply dismissing them outright, Robinson takes these figures to account on the basis of their own words, dissecting the ugly mess of hateful nonsense beneath whatever persona they’ve created for themselves.

Current Affairs is a decidedly leftist publication; it routinely condemns capitalist excess, corporate misconduct, “bipartisan” alliances with murderous regimes, the convenient political amnesia concerning America’s history of horrific military interventions, the dark legacy of racism at the root of deep social and economic inequalities.

While it writes of socialism as a political and economic alternative, the magazine has been equally critical of authoritarian socialism. Robinson’s own essay, “How To Be A Socialist Without Being An Apologist For The Atrocities Of Communist Regimes“, puts it quite plainly:

The dominant “communist” tendencies of the 20th century aimed to liberate people, but they offered no actual ethical limits on what you could do in the name of “liberation.” That doesn’t mean liberation is bad, it means ethics are indispensable and that the Marxist disdain for “moralizing” is scary and ominous.

Current Affairs instead leans towards libertarian socialism, an ideology seeking to balance a high commitment to individual freedom with a concern for the welfare of societies. It speaks of “humanistic” values and holds all ideologies to account for living up to those values.

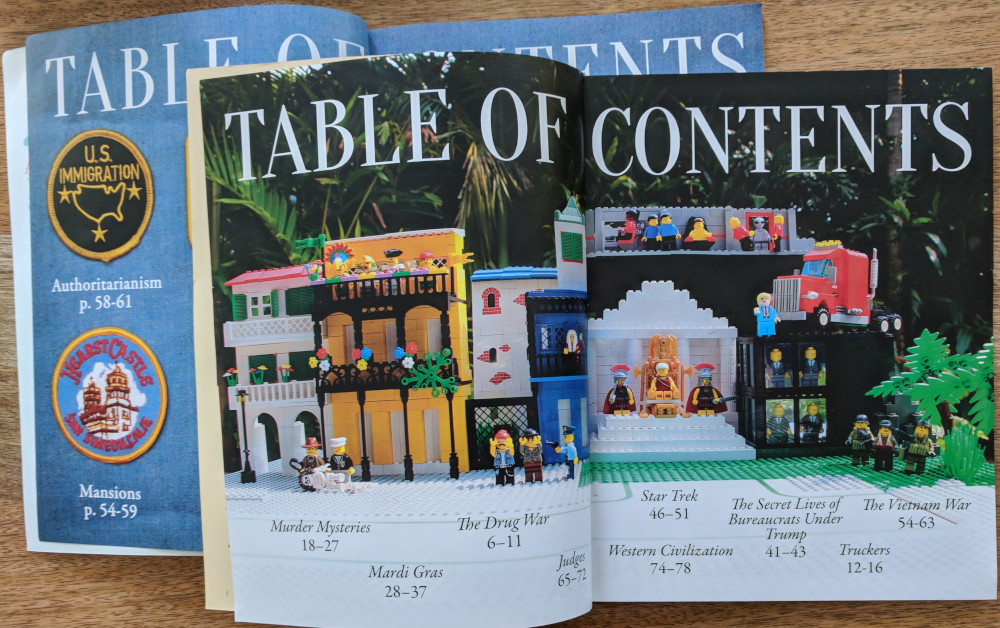

The magazine publishes essays about diverse topics from the changing politics of Star Trek to the Mardi Gras holiday in New Orleans. You’re in for a visual treat the moment you open the table of contents, each of which is an artistic exploration of the topics covered in the current edition.

Current Affairs table of contents examples. (Credit: Current Affairs. Fair use.)

Alongside its playfulness and occasional silliness, the magazine features articles such as a gut-wrenching and unflinching look back at the Vietnam War (“What We Did”) or an insightful report on disillusioned African-American Rust Belt voters (“The Color of Economic Anxiety”).

Recently, the magazine also launched a podcast; as of this writing, it is already generating more than $6,000/month in Patreon support (supporters get access to bonus episodes). The podcast features conversations between the magazine’s contributors on a wide variety of topics, featuring segments like “Lefty Shark-Tank” (tongue-in-cheek criticism of left-wing policy ideas), interviews, answers to listeners, parody ads, and more.

Legally, Current Affairs is not a nonprofit; Nathan Robinson told me by email that the team “debated it and then decided against it as it creates all kinds of logistical headaches”.

However, he emphasized that Current Affairs will never operate as a for-profit company. Over the course of each magazine’s two-month run, all articles are published online without any kind of paywall, and the website and magazine are entirely free of third party ads. Regrettably, articles are under conventional copyright, as opposed to a permissive Creative Commons license.

Article example from the latest issue. (Credit: Current Affairs. Fair use.)

The Verdict

After reading their online edition for a while, I subscribed to Current Affairs earlier this year, and have not regretted it yet. At $60 for 6 issues, you get good value for your money; the magazine is a pleasure to look at, and I generally read it all the way through before the next one arrives.

A few typos usually slip through, and some articles would benefit from more rigor (data, citations) or additional editing. But these are the kinds of problems you would expect from a small, independent magazine.

In many ways, I prefer the Current Affairs model to the heavily grant-funded nonprofit publications I’ve reviewed (e.g., The Marshall Project, ProPublica). It will likely never be able to muster the resources to engage in a similar scale of reporting projects, but its writing is fearless and independent, funded entirely by readers. While its humor can be snarky, underneath it there’s an earnestness that’s disarming and likable. I highly recommend checking it out.

Would you enjoy reading it? Fortunately, that’s easy to find out by browsing the archives of the website. Regardless of its legal status, I’ve also added it to the Twitter feed of quality nonprofit media, which is a convenient way to sample the content of many nonprofit outlets if you happen to use Twitter.

Quanta Magazine is one of two websites published by the Simons Foundation, the vehicle for hedge fund founder James Simons’ philanthropic giving. Quanta focuses on mathematics, physics, computer science and biology. The other publication is Spectrum News, which covers autism research.

The Simons Foundation had more than $2B in net assets as of its 2015 tax return; Quanta is essentially one of its gifts to the public and does not rely on additional support. This makes it similar to Mosaic (reviews), published by the even more massively endowed Wellcome Trust. However, it publishes a lot more frequently: Mosaic tends to publish 2-4 long-form articles per month; Quanta publishes more than a dozen medium-sized articles in the same timeframe.

Financial background

The name Quanta evokes the source of James Simons’ $18.5B fortune: quant investing. Simons, who worked as an NSA codebreaker at age 26, has been described as “the mathematician who cracked Wall Street” for his use of highly sophisticated mathematical models to predict profitable trades. His personal wealth derives from his hedge fund, Renaissance Technologies, which the MIT’s Andrew Lo called the “pinnacle of quant investing” and “the commercial version of the Manhattan Project”.

In 2014, Renaissance was interrogated by the US Senate for the use of an obscure loophole to avoid an estimated $6.8B in capital gains tax, an amount which far exceeds the endowment of the Simons Foundation. Its name has made the news for another reason: Renaissance co-CEO Robert Mercer is one of the biggest backers of Donald Trump’s anti-science Presidency and of the far right, anti-intellectual propaganda outlet Breitbart News, while Simons himself backed Hillary Clinton.

While the philanthropic impulses of the company’s principals are clearly contradictory, Quanta’s editorial beat is unlikely to conflict with Renaissance’s financial origins. Quanta itself has this to say about its editorial independence:

All editorial decisions, including which research or researchers to cover, are made by Quanta’s staff reporting to the editor in chief; editorial content is not reviewed by anyone outside of the news team prior to publication; Quanta has no involvement in any of the Simons Foundation’s grant-giving or research efforts; and researchers who receive funding from the foundation do not receive preferential treatment. The decision to cover a particular researcher or research result is made solely on editorial grounds in service of our readers.

Scope, design, navigation

Quanta’s stated goal is to “illuminate science”. In practice, this translates to articles that seek to arouse curiosity rather than controversy.

Where a magazine like Mosaic doesn’t shy away from in-depth articles about abortion rights in India and the US or sex workers in Mozambique, Quanta tends to write about questions in science that are both interesting and not highly politicized. Over a five-year period, I only found two feature articles with a strong political dimension: “A Physicist Who Models ISIS and the Alt-Right” and “How to Quantify (and Fight) Gerrymandering”. Zero articles about abortion, zero about transgender or homosexuality, one whose primary topic is climate change.

This is not a criticism; there surely is a place for a publication like this, which may succeed in reaching people across the political spectrum and promote a greater interest in science itself. Indeed, for the topics it does tackle, Quanta often succeeds spectacularly at making complex topics accessible and interesting.

This starts with the website design: Quanta is easily one of the most beautiful sites we’ve reviewed. The design leaves a lot of room for large-format images, while scaling well onto mobile devices, as well. Careful use of typography, color and whitespace gives the articles an aesthetic that brings together elements of print and the web in a very appealing manner.

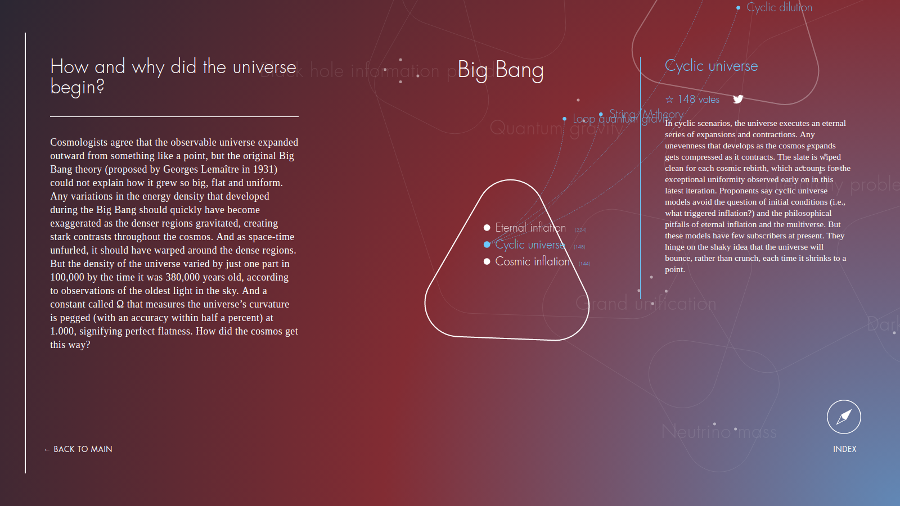

Quanta sometimes publishes interactive micro-sites, such as this explorable (and information-rich) map of current contenders for a “Theory of Everything” (Credit: Quanta Magazine. Fair use.)

Alongside recent articles and features, the front page highlights videos, podcasts, most-read articles, and “recommended features” (which includes articles from previous years). Individual pages include tags like “Microbiology” or “Podcast”. Overall the site is easy to navigate. Most content loads without JavaScript enabled, though some site features will break and leave behind empty boxes.

Content examples

Quanta’s reporting on bacteria and biofilms is illustrative of how it approaches complex topics. The feature story, “Bacteria Use Brainlike Bursts of Electricity to Communicate”, recaps well-understood principles of chemical communication in bacterial colonies, and adds recent findings regarding ion channel communication.

The story is supported by quotes from multiple scientists (five from the United States, one from Spain and one from Italy). It includes a GIF animation that was carefully adapted from YouTube videos published by one of the scientist teams. The writing and approach is similar to Scientific American. In fact, the article was also syndicated to its website, and the author has bylines there and in other science magazines.

Quanta published a related feature titled “Seeing the Beautiful Intelligence of Microbes”, which shows many more examples of biofilm and slime mold behavior, again often employing large format GIF animations. This underscores the magazine’s willingness to go beyond the limitations of a print magazine. It’s a visually stunning feature that even readers with limited scientific interest may enjoy.

Expansion of Pseudomonas biofilm, an example of the kind of carefully produced GIF animation that makes many Quanta articles visually outstanding (Credit: Quanta Magazine. Fair use.)

A more elaborate example is Quanta’s 2015 map of “theories of everything”. It’s an interactive full screen overview of physics concepts like loop quantum gravity and the holographic principle, organized into the larger and overlapping areas of knowledge they relate to. This is the kind of resource you may end up returning to as you read about these topics in the news.

Some Quanta articles are accompanied by podcast episodes. Episodes are featured as a prominent “play” button at the top of a regular article for the relevant episode, which looks like an effective way to draw in listeners who don’t typically subscribe to podcasts.

There is also a YouTube channel. As with many other nonprofit publications, it reaches a relatively small audience of less than 10,000 subscribers, though some of the educational videos (e.g., “What is a species?”) are quite good. There are many education/science YouTube channels with orders of magnitude more subscribers, so perhaps a partnership would be more successful at reaching a large audience.

Licensing

Quanta articles are frequently syndicated to other publications. They are under conventional copyright; in response to an inquiry, a staff member stated that there are no plans to consider a Creative Commons license. This is regrettable: much of the text, image and video content would be useful for open educational resources.

Like Mosaic, Quanta’s funding is secure thanks to a large endowment; it’s not clear why an open access license is off the table. As it is, we can enjoy Quanta for free, but we cannot re-use it and build on it without permission. It is a gift, but one with strings attached.

The Verdict

Quanta succeeds in its mission of making scientific topics accessible, often in a way that inspires further exploration and learning. It’s a beautiful website that makes good use of the web as a medium–through animations, large format photographs, videos, interactives, well-integrated podcasts, and so on.

I recommend following Quanta’s work to any curious person. While I would love to see it under a Creative Commons license, this does not impact the rating per our standard criteria. 5 out of 5 stars.

In the social and political upheaval of the 1960s and 1970s, many socialist and progressive publications were born. Most are long gone; New Internationalist, founded in 1973 in the UK, is a notable exception. Not only has it survived well into the 21st century, it has proven its adaptability through a crowdfunding campaign that raised more than $900K in donations.

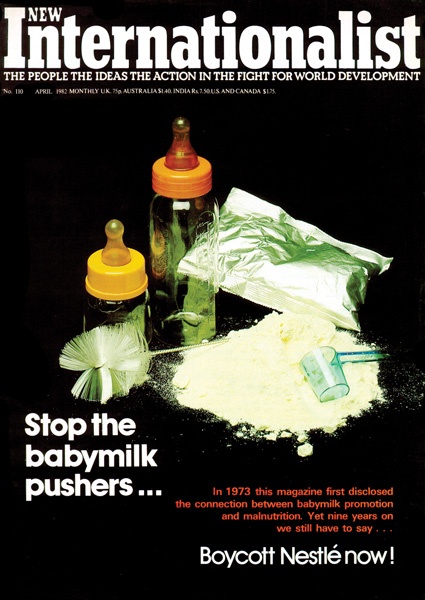

Through its history, the publication has focused on liberation and decolonization movements around the world and on the global impact of unbridled capitalism. It was one of the first publications to highlight the dangers of Nestlé’s efforts to market infant formula milk in the developing world; decades later, it played a similar role in raising awareness of fracking.

A significant part of New Internationalist’s ethos is to “give space for people to tell their

own stories”, that is, to feature international writers instead of Western “experts” and correspondents. This helps to lend an authenticity to its reporting that many other publications lack.

The provocative April 1982 cover of New Internationalist, revisiting the issue of infant formula milk.

New Internationalist also operates the Ethical Shop, which sells books, calendars, clothing, and various other merchandise. This includes original publications, such as the series of “No-Nonsense Guides” on topics ranging from global finance to drug legalization. Other products are sold together with partner charities. The shop follows a Buying Policy that seeks to promote good labor and environmental practices.

While it tends to support left-wing politics, New Internationalist is not an explicitly socialist magazine.

Finances, Transparency, Impact

Many of the US-based nonprofit media we have reviewed are dependent on grants, awarded from the fortunes amassed by the likes of Bill Gates, Michael Bloomberg, George Soros, Herbert Sandler, or previous generations of industrialists. This can create a bias towards elite audiences and away from highly contentious topics (see, e.g., Rodney Benson: Can foundations solve the journalism crisis?).

In contrast, the revenue supporting New Internationalist comes from people buying digital and print publications, or ordering other products from the Ethical Shop. This is broken down in percentages in the 2013/14 Annual Report, which does however not include GBP (£) figures. Indeed, the New Internationalist website includes no direct reference to organizational internals, and I did not receive a response to a contact inquiry asking for more recent information.

This lack of transparency is all the more regrettable given that the organization is run as a co-op with a non-hierarchical structure, very unlike the top-down model that is typical for US nonprofits. The rest of the world would benefit from learning more about this approach from those who practice it.

The UK Companies House report for New Internationalist Publications Ltd. shows net assets of 853K GBP (about 1.15M USD) as of March 31, 2016.

As of this writing, New Internationalist has about 37.8K followers on Twitter and about 80K on Facebook. These numbers should have some room to grow; consider, for example, that Positive News (also UK-based, also a co-op, with a smaller budget and smaller print circulation) has about 260K Facebook followers.

Design and Apps

The New Internationalist website is a minimalist feed of articles that mixes shorter posts and features, without any apparent prioritization beyond recency. Stories are tagged with regions and topics, which can be used to explore the large library of articles. The site is reasonably mobile-friendly. Some readers may have difficulty with the relatively low contrast color scheme (an unfortunate recent design trend).

As with many publications from the print era, only a subset of New Internationalist content is available for free online. If you prefer digital over a print subscription, you can purchase and read the magazine on Android or iOS devices via the respective apps (New Internationalist for Android, New Internationalist for iOS).

The Android app works well enough, though there are a few annoyances; for example, wide tables require horizontal scrolling, but accidental “swipe” gestures trigger moving from one article to the next, making it almost impossible to actually view wide tables. On the plus side, the article text is readable, and tables are presented as tables rather than as embedded images.

You can purchase full copies of the magazine via the Android and iOS apps.

An alternative to buying copies through the apps is purchasing them through Zinio and reading the magazine through its dedicated reader. As far as I can tell, there is no option to purchase and download DRM-free PDF files, and I found no evidence that any part of New Internationalist (web or app) is developed as open source software. New Internationalist articles are under conventional copyright (as opposed to a Creative Commons license).

Content Example: “The Equality Effect”

While not all content is available for free, many feature stories are posted in full. “The Equality Effect” is such a feature story, written by Danny Dorling, Professor of Geography at the University of Oxford and author of a book with the same title. In fact, much of the July issue was dedicated to the issue of inequality and edited by Dorling.

The article is analytical, making the case that inequality is the source of a large number of social ills, and not at all unavoidable. Rather than promoting a specific political ideology, Dorling is making a case to consider policies addressing inequality on their merits:

Although leftwing and green politicians tend to advocate greater equality more vocally, and rightwing and fascist ones tend to oppose it, equality is actually not the preserve of any political label. Great inequality has been sustained or increased under systems labelled as socialist and communist. Some free-market systems have seen equalities grow and the playing field become more level. Anarchistic systems can be either highly equitable or inequitable.

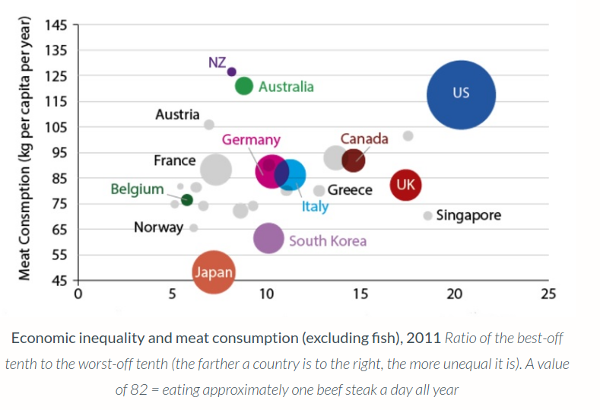

At the bottom of the article is a carousel of “related articles”, some from the same issue. It’s easy to miss that Dorling wrote another piece in the July issue expanding on his argument: “The rich, poor and the earth”. It cites additional data and attempts to show correlations between inequality and waste production, CO2 emissions, and meat consumption.

As presented, this chart does not support the thesis of the article that inequality is meaningfully correlated with meat consumption, let alone that there is a causal relationship.

Skeptical readers will find the analysis here to be lacking in rigor. Dorling dismisses outliers; in the case of the “meat consumption” chart, France, Germany, and the UK show very similar levels of meat consumption in spite of large differences in inequality. Eliminate the US and even the appearance of a correlation largely disappears; in any case, a correlation coefficient is not given.

With these kinds of charts, there are many ways to demonstrate the result you want: by cherry-picking countries, by picking the measure of inequality that shows the strongest correlation, and by only considering alternative explanations for data points that disagree with the hypothesis (“their cultural histories are bound up with the rearing of sheep and cattle”).

Data scientists warn that much more visually compelling spurious correlations can be found between many completely unrelated measures, and that even peer reviewed science is routinely subject to data dredging and p-hacking. “Science isn’t broken, it’s just a hell of a lot harder than we give it credit for,” warned a must-read article by FiveThirtyEight science writer Christie Aschwanden.

The thematic focus on inequality is laudable, and it makes sense that New Internationalist would invite an accomplished academic writer on this topic as guest editor. In fact, the much larger Guardian also published Dorling’s bubble chart analysis uncritically. Still, we should expect a greater level of empirical rigor in unpacking complex issues such as this one.

Content Example: “The Many Roots of Homelessness”

“Civil war, mental illness, poverty, gang violence: the many roots of homelessness” is a more conventional storytelling piece from the June issue that shares personal narratives of people experiencing homelessness and housing insecurity from the Philippines, Great Britain, the United States and, Mexico.

This short article showcases New Internationalist’s strength in featuring authentic voices from around the globe. For example, Maria from the Philippines describes the economic pressure which forces her family to live in a slum:

We found a room for rent in the nearby block. It cost $50 a month. It’s expensive and eats a huge chunk of Marvin’s monthly income of $119. I can’t work yet because I have to take care of our baby, Mark. So this is our home for now.

This kind of storytelling is crucial to overcome stereotypes and to challenge the stigma often associated with homelessness.

The Verdict

New Internationalist is important: it sheds light on underreported injustices and amplifies the voices of activists who seek to bring about positive change. As a left-wing publication, it occupies a relatively lonely space by taking an impact-oriented international view without being stridently ideological.

It has outlasted many other magazines and successfully made its way into the 21st century, but not without stumbling. The website and apps still have a few mostly minor bugs; the site design suffers from small readability issues and lacks clear organizing principles; the level of transparency is below some other mature nonprofits of similar size (compare Truthout’s timely and comprehensive Annual Reports, for example).

You will find many stories here that nobody else is covering, with larger ambition and reach than other publications we’ve reviewed, and the editorial quality is generally high. When tackling complex topics, New Internationalist would benefit from more rigorous internal review to ensure the highest possible quality of reporting. Recommended; 4 out of 5 stars.

Team blog

A checklist for reviewing nonprofit media

We have now published a few reviews of non-profit media. Let’s take a closer look at the criteria we can use to assess a non-profit publication (many of which also apply to for-profit media) and how they should influence a source’s rating.

Funding sources

How a source is funded may influence what it reports on. We currently do not review publications that are primarily funded through advertising or by taxpayers. The types of media we are interested in receive funding primarily (>50%) in one or more of the following ways:

- from individual major donors

- from individual small donations

- from foundations that award grants, fellowships, etc. (more on this below)

- from subscriptions

Each of these revenue sources has its own challenges, with subscriptions or small donations providing the broadest base of support and therefore the least leverage for any individual supporter; the effect of such a model does then depend largely on what most the supporters expect from the thing they’re supporting (even neo-nazi websites like Stormfront use funding from individual donors to survive).

The Intercept is an interesting example for how support from a single large donor can grant a significant measure of editorial freedom. The non-profit behind it, First Look Media, was funded by billionaire Pierre Omidyar, receiving $30M funding in its first year. But of course this presents major vulnerabilities as well. There is the possibility of behind-the-scenes meddling, or the organization might simply run out of money.

When major donors become philanthropists, they often set up foundations. These organizations give in accordance with their funders’ wishes. Many of them operate large endowment funds, which generate investment income indefintely (see Wikipedia’s list of the wealthiest foundations).

Non-profit media can apply for grants from foundations, and some rely primarily in such support – see the ProPublica list of supporters, for example. Heavy reliance on foundations may introduce a status quo bias: typically the creation of millionaires or billionaires, they are usually founded with the intent to advocate for an incremental change agenda within the existing political and economic order. They are also reputation-sensitive, and do not themselves want to be targeted by political groups. Their internal decision-making processes may reflect these biases, and penalize grant applicants who propose overly radical projects.

Such concerns are not unwarranted, as the intense targeting of one of the most progressive funders, George Soros’ Open Society Foundations, by right-wing groups demonstrates. Progressives – who are notoriously skeptical of billionaires’ intentions – don’t necessarily jump to their defense, either. As a result, many other philanthropists avoid politics entirely, and focus on diseases, poverty, or other social ills.

There are, of course, also countless reactionary foundations. Organizations like the “Center for Organizational Research and Education” are funded by corporations to advance their agenda, by discrediting scientific research or activist efforts. And progressive organizations like the Center for American Progress have received funding from corporate donors and foreign countries.

To uncover funding networks, the following resources are helpful:

- The ProPublica Nonprofit Explorer, GuideStar and Charity Navigator mine the tax returns (form 990) of US-based non-profit organizations, which include high-level revenue data and top executive compensation.

- Many established charities publish Annual Reports, though they can be difficult to find. Use a Google search with

site:<domain name>. These reports usually include a funding breakdown by source (foundations, individual donations, etc.). - Separately, charities may have pages with names like “Benefactors” or “Our supporters” that list key major donors by name.

- A news search for the charity’s name, the Wikipedia article, and other external sources may provide additional information.

Relation to rating: The funding model should not influence a source’s rating.

Executive compensation

As noted above, US non-profit tax returns do include top salaries. Needless to say, appropriate compensation is highly dependent on geography, and also correlates with organizational size (running a large, complex organization requires a different skillset that warrants higher compensation). With that said, it’s useful to compare executive compensation with non-profits of similar size in the same region. Is it extraordinarily high?

If the organization is currently dependent on a few large revenue sources like major donors and foundations, excessive compensation may make it more difficult to achieve a broader base of support as soon as these numbers receive greater scrutiny. And of course there’s the practical question of how much the charity can achieve for a given dollar if it pays more for certain roles than it needs to.

Relation to rating: This should only influence a source’s rating to the extent that it appeals for public support.

Overhead vs. Waste

You may have heard of “overhead ratios” and similar efficiency assessments: how much of a charity’s work goes towards programmatic work (such as journalism) and how much goes towards administrative support (such as fundraising, office equipment, etc.).

These ratios are now widely regarded as counterproductive by nonprofit experts, because they can be easily gamed (the functional allocation of expenses is done by the nonprofit itself and contains a lot of loopholes), because honest organizations may get penalized, and because they may disincentivize necessary investments that increase the organization’s effectiveness.

As such, I never look at an overhead ratio by itself, but I do scrutinize Annual Reports, financial statements and other records to look for evidence of wasteful spending. An example would be excessive spending on executive offsite meetings, consultants engaging in runaway planning projects, and so on.

Relation to rating: Wastefulness should influence a source’s rating to the extent that it appeals for public support.

Transparency

This brings us to the broader question of what we can learn about an organization and its inner workings. The information I expect to find on a well-run non-profit’s website includes:

- information about the tax deductibility of donations

- the latest Annual Report or at least a list of benefactors

- the latest tax returns and financials

- information about the Board and Staff (at least leadership)

- contact information

If such information is nowhere to be found, that doesn’t mean anyone is trying to hide something. Organizations go through stages of development, and developing an understanding of good governance is part of that process. What’s disappointing is when a well-funded organization does a poorer job with this than a scrappy one.

Relation to rating: A well-established, well-funded organization can be penalized for lack of transparency.

Positioning

A source may position itself in different ways, e.g., as center-left, or religious right, or far left, and this may be expressed in the form of editorials, analysis, and most importantly, coverage. Which stories receive attention and why, and which ones don’t? Which views are dismissed as “unrealistic” or “extreme”? Does the source obsesesively target the same person over and over again, resulting in an unbalanced perception of reality?

I don’t believe that there is “neutral” positioning for a news source. Selection of topics, scope of coverage, placement of stories, etc. are all “opinionated” decisions, made by humans with a perspective on how the world works, or by human-created algorithms optimizing towards a specific outcome like ad revenue. Nobody would want to read an actually neutral news source: positioning and curation are crucial functions of all news media.

In order to identify positioning:

- We can look at the way a source describes itself, or the founder has described it.

- We can look at the aforementioned funding questions to give us some clues. Funders with specific leanings tend to fund consistently with those leanings.

- We can spot check topical coverage:

- How are climate movements like “Keep it in the Ground” treated?

- How are different political candidates treated?

- How are revelations by major whistleblowers like Edward Snowden presented?

- We can look at the editorial pages. Do they restrict themselves to a narrow band of opinions, and if so, which band is it?

- What “experts” are consulted by the source? (See SourceWatch’s list of industry-friendly experts, for example.)

- Does the publication engage in false balance?

Relation to rating: Positioning itself should not influence the rating, but answers to the above question may, especially insofar as they relate to manipulative intent (see below).

Manipulative intent, gross negligence, sensationalizing

Beyond their positioning (which shapes our views through what is included and excluded), media can manipulate our views is subtle and notoso-subtle ways:

-

Deliberate distortion. The typical example would be an out of context quote. This has been noted in the example of UK politican Jeremy Corbyn, for example: How to speak Corbyn: A Headline Writer’s Guide But there are many other ways to misrepresent a story, omit crucial context, or sensationalize. Clickbait sites on the left are not immune to this charge.

-

Gross negligence. Imagine building a whole story on the basis of an unverified tweet by a random person on the Internet. Pipelines of media can normalize gross negligence: from Twitter to Infowars or Zerohedge to Breitbart or Daily Caller to National Review or Fox News.

-

Sensationalizing. The classic example here is the tabloid screaming of a scandal in letters taking up much of the page. The more modern example would be a clickbait headline. A source may report something real, but may do it using hyperbolic language, moral condemnation, exaggerated interpretations, calls to action, and so on.

In all these cases, it’s worth looking not just for evidence that such things occur (which is fairly easy, and supported by fact-checking sites like Politifact, Snopes, and so on), but also whether they follow a pattern consistent with the source’s positioning.

Relation to rating: A source may be penalized consistent with the extent to which it engages in these practices.

Mechanism for corrections

Is there a way to report an error? If so, does it actually result in any acknowledgment or follow-up? I highly recommend testing this with any source whenever you spot an error. The results can be enlightening.

Relation to rating: This is a minor consideration.

Scope

What does the news source actually cover? Is it a global, national, locally focused source? Is it restricted to certain topics? Does it include editorials, news, original interviews, cartoons, etc.? The answers shouldn’t reflect well or poorly on the source, but do help readers decide what other sources they might want to add to their mix to even things out.

Relation to rating: Scope should not affect the rating.

Reader engagement

Does the source have a discussion forum? If so, does it have any moderation mechanism, protection against forum spam, etc.? Are there other ways for readers to get involved, e.g., through citizen journalism projects?

Relation to rating: This is a minor consideration.

Licensing

Most content is uner conventional copyright: you can’t use it without the author’s permission (fair use exemptions notwithstanding). For organizations dedicated to advancing the public interest in some way, this can be dissonant. There is an alternative: Creative Commons licensing. It lets an author say: “I want anyone to be able to use it, but only if they credit me by name”. Or “I want anyone to be able to use it, but not commercially.”

Wikipedia, for example, uses the Creative Commons Attribution Share/Alike-License. It requires attribution, and if you share a modified version, your changes have to be made under the same terms. This license is also used by some non-profit media, such as Common Dreams. Many, however, likely have never heard of this option.

Relation to rating: This is a minor consideration.

Team Profile

We believe the profit motive harms the integrity of information in news media. It incentivizes sensationalism and introduces coverage biases toward owners and advertisers.

We’re on the look-out for media sources that follow a different funding model or are entirely volunteer-driven.

Highly reviewed national or international English language media are added to this Twitter list, which lets you easily subscribe to the whole batch or follow individual ones you care about.

Our current top 5 to review:

Number of members: 8 (view list)

Number of reviews: 27

Moderators:

- Eloquencefounder

Any source tagged with this team must not be primarily advertising funded. We don’t currently aim to review primarily state-funded media.

See our detailed checklist for tips on what to look for and how to rate.