Reviews by hay

In a dystopian and industrialised world, the Shinra Electric Power Company rules over the city of Midgar in all its facets.

The company exploits a natural resource called Mako for energy generation at great environmental cost.

The game starts with you in the shoes of Avalanche, a small group of eco-terrorists on a mission to destroy one of Shinra’s Mako reactors.

Throughout the game, Avalanche’s conflict with Shinra escalates further as they retaliate and the group’s members grow closer together. But something isn’t quite right…

Final Fantasy VII Remake, as the title suggests, is the remake of the 1997 gaming classic Final Fantasy VII by Square.

Remaking a famous game like that comes with a lot of pressure to live up to the beloved original but also creative opportunities.

Firstly, you have an established foundation to build on with decades of hindsight regarding what did and didn’t work at the time.

And secondly, a lot of players will be somewhat familiar with the original.

This familiarity allows for a unique dialogue with the audience—what you decide to keep and what you decide to change.

Within the context of a remake, these aren’t merely choices but active communication. And FFVII Remake, as it turns out, is very talkative.

The nature of the remake

First, to dispel some potential confusion, this is not a complete remake of FFVII as the name might imply. It is, instead, the first entry in a recently announced trilogy. In the original game, eventually, you get to explore the world outside of the city, but that’s all you will see in this remake.

Obviously, stretching FFVII like this is the result of corporate demand. They weren’t just going to remake a cultural titan like Final Fantasy VII and call it a day. And while the profit-driven endeavours of big publishers like Square Enix grow more shameless by the year, I can’t deny that I am fascinated by what developers manage to do creatively with these business-mediated constraints. Suffice it to say, I think they succeeded in creating something quite special here.

In one way, it’s exactly what you would expect from a remake like this, but in another, it completely defies those expectations. Even more impressive is that the game walks this tightrope of seeming contradictions very well.

As far as the gameplay is concerned, FFVII Remake gets the action RPG treatment. These changes bring it in line with other contemporary Final Fantasy releases like FFXV. And when it comes to the adaption of the story for the remake, things are simultaneously similar and different. Certain things and scenes are adapted very faithfully. For example, the famous introduction to the original is adapted beat by beat. But it doesn’t take long for you to notice major structural differences between the two games. In this review I will mainly focus on the differences and how most of them enhance the original.

Extended world and characters

The general throughline with JRPGs hasn’t changed much since 1997. There is a greater focus on action for the gameplay now, but as far as it goes with the story, characters, and world-building, things are virtually the same. We have a linear spectacle-driven narrative with a diverse cast and a greatly fleshed-out world. With this remake taking the first quarter of FFVII and fleshing it out to about 35 hours, it has room to explore these narrative elements in a depth the original never could. Most immediately apparent is this in the characters. Every single one of them has something new going for them. From small things, like Barrett, the charismatic leader of Avalanche being afraid of heights, over Tifa, another Avalanche member, having frequent doubts about the group’s whole terrorism thing, to major character changes. The most prominent example of such character changes is Jessie. In the original, she is a relatively minor character, but now she is treated with the same attention as major playable ones. She gets much more screen time and further an extended backstory into how her father’s work for Shinra radicalised her into joining Avalanche.

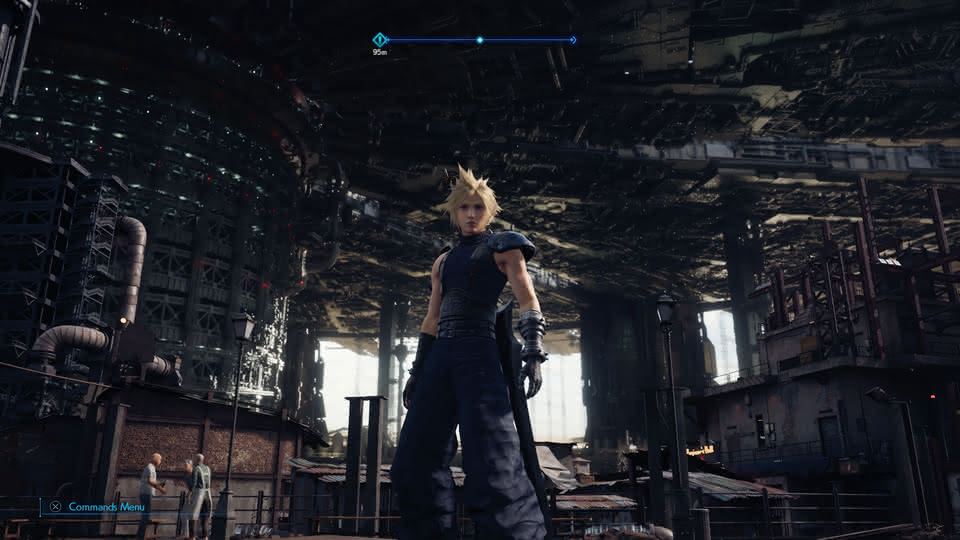

I also should not dismiss what modern hardware capabilities brought to the table. In the original, the 3D models for characters were rough approximations of human anatomy, stiffly animated, where individual polygons were visible. Now, three console generations later, we get richly detailed characters, that smoothly move through their scenes and the world. The new voice acting breathes in the final bit of life into these characters. It gives the game a whole new overall feeling.

Not only do the enhanced visuals sell the characters much better, but also the world as a whole. The best example of this is the city itself. The population of Midgar is greatly divided by class, which was already made clear in the original by having two levels to the city The upper level is built on plates arranged in a circular shape, suspended in the air. Here industry and commerce are situated, including the Mako reactors and Shinra’s headquarters. Most Shinra employees appear to be living here.

The lower classes of Midgar society live in slums on the ground below the plates. So the lower classes are constantly reminded of their social standing with this subtle visual metaphor. In the original though, this wasn’t always that apparent with its fixed top-down camera angles. Now, with the third-person camera following your character, you can look up all the time. It might sound small, but this constant reminder about Midgar’s class divide adds so much to the overall experience.

Looking up from the slums (Credit: Square Enix. Fair use.)

But this remake also finds entirely new ways to comment on the hyper-capitalist nature of Midgar. If you are familiar with Final Fantasy, you will know about Potions. They are a family of generic healing items that have been with the series since the beginning. In FFVII Remake, instead, Potions are produced by a huge corporation. And naturally, the game world is littered with advertising and vending machines for Potions. This repurposing of familiar core elements of the series for thematic ends is genius. Again, it might seem small, but it adds so much to the overall character of the world.

(Credit: Square Enix. Fair use.)

Dealing with FFVII’s narrative legacy

The remake largely follows the events of the original. But the way the game does this is anything but typical. If you are familiar with the original story, you will quickly notice small divergences. For example, the remake introduces the primary antagonist Sephiroth right after the beginning, whereas, originally, that would be a few hours away from that point. These small changes in compound foreshadow much more large-scale changes in the story, but when that fork in the road is reached, something strange happens.

There are forces at work to push back from the story changing too much. When a major divergence in the story is about to happen, ghostly figures called Whispers breach onto the scene and prevent the change from happening. They block the hero’s path or remove characters from the scene before some revelatory backstory could be delivered too early. The Whispers forcefully bring this remake’s story into accord with the original.

What exactly the Whispers represent isn’t clear, but they appear to be the writers’ literal manifestation of anxiety over making changes to the story of a game as beloved as Final Fantasy VII. Anxiety over done changes not being as good as they thought, or, sadly more likely, anxiety over backlash from fans for any changes having been made at all. It asks interesting questions about the nature of remakes. Should developers merely modernise the old and keep with the original’s spirit, or are massive changes—a completely different game even—okay?

In the video game space, we have many faithful remakes. And even in this game, it seems like the Whispers are winning with another modernised but structurally untouched game. But at the climax, our protagonists challenge fate itself and come out victorious. As our heroes prepare to leave Midgar, the game breaks the fourth wall letting us know that the story for this remake’s sequel is yet untold. Thus with the end of the game, we reach the long foreshadowed fork in the road, and the game goes full speed into the unexpected. What an incredible statement!

Avalanche’s revolution

Despite Final Fantasy VII Remake refraining from making major structural changes to the original’s story until the finale, the changes up until that point can’t exactly be called minor. The most noticeable changes lie with the overall politics of the game, and thus with the terrorist group at the heart of the narrative: Avalanche.

There are two important differences in how the remake approaches the group. The first is in how the game frames Avalanche’s actions, and the second is in what Avalanche does. The reframing has two goals: making the group’s antagonism against Shinra more realistic and painting the group as more sympathetic.

Firstly, Avalanche is part of a wider resistance network now. In hindsight, it was a bit weird with a mega-corporation sucking the life essence from the planet that only a handful of radicals chose to take action against it in the original. This change makes their struggle much more believable.

Another such change that reframes the actions of the group is the bombing mission in the intro. In the original, blowing up the Mako reactor causes a chain reaction that destroys the reactor and its immediate neighbourhood. Contrast that with the remake, where they only plan for a small and controlled explosion to take out the reactor core. But when Shinra’s president gets wind of the plan, he gives the order to destroy the reactor from the inside, which triggers a chain reaction all the same. The company blames the resulting destruction on Avalanche.

At the end of the mission, the game makes you walk through the destroyed streets of Midgar with injured people and onlookers everywhere. While Jessie theorises about what she might have done wrong to trigger the greater explosion, you the player, know that Shinra is to blame. This reframing makes Avalanche immediately more sympathetic to newcomers. It would be much harder to empathise with them just blowing up a reactor in the knowledge that innocent people would die, regardless of their motivation. It also nicely foreshadows the much worse things Shinra will do later.

But not everyone is willing to go as far as Avalanche or even thinks the status quo is bad. When the team arrives in the slums after the bombing mission, a man is tearing down pro-Avalanche posters. He makes it clear that he thinks what Shinra is doing in Midgar is progress. He looks up at the steel plates and sees progress, not oppression. It makes a lot of sense. Shinra couldn’t do what they do without many willing participants. Does that remind you of something?

It is clear that the much increased awareness of the ensuing climate catastrophe is the reason for this remake’s increased radicalness. Not only has the environmentalist message of the original FFVII not aged a bit, but it was updated to be allegorically about climate change. Because of this, the parallels are so stark. And it also allows FFVIIR to delve into a lot more adjacent topics in a seamless manner. The game explores how corporate media manufactures public opinion that is beneficial to the powerful. It explores how despite Shinra being a gigantic threat to the planet, many people choose to be complicit.

But even more interestingly, the game shows how radical revolutionary groups can structure themselves.

When looking at revolutionary struggle, it is easy to overemphasise the big event. In the case of FFVIIR, that would be destroying Mako reactors. But it is arguably much more important to aid in the creation of a revolutionary society that can facilitate the fought for change. This game makes this clear by focusing on community building between the big story moments. You do this by helping the people in the slums in their daily struggles. And as a bonus, it nicely slots into the familiar side questing structure of most JRPGs.

Later, when Shinra unleashes horrifying death and destruction upon the slums in revenge against Avalanche, you are the one organising an evacuation from there, managing to save a lot of lives.

The general handling of this event is curious in comparison to the original. Not only does no such evacuation take place there, but also later, this event is used as the catalyst for Barret to regret his radical actions. He accepts the responsibility for what happened because Shinra was reacting to Avalanche−violence begets violence, that’s the moral of the story. This remake rejects this both-sidesism, giving us an energetic and angry Barret, who blames Shinra completely for what they have done. This change greatly elevates the story because this acceptance of personal guilt severely undercuts core messages of the original and trades it with an unsatisfactory conclusion.

It might sound somewhat contradictory, but this remake is simultaneously broader and more focused than its predecessor in its political messaging. It’s also a lot more angry and empathetic. I love it.

Action Time Battle

The gameplay is quite similar to the story. In many ways, the remake builds on and pays tribute to the original. This manifests in small parts in the few mini-games across the game, getting a modern do-over and polish, or even introducing new ones. But when it comes to gameplay, most people will think of the combat.

The remake attempts a fusion of the original FFVII’s combat and the combat of the most recent series entry, Final Fantasy XV.

In this fused combat system, you have over-the-shoulder control of a character, triggering combat actions on button presses. However, in contrast to XV, you can switch between characters on the fly. If there are enemies high up in the air, and they become inconvenient to reach with Cloud because he is a sword fighter, you could switch to Barret, who has a rotary cannon for a hand.

Another distinguishing factor from FFXV is the menuing. When you open the menu during combat, time slows down, and you have the space to deliberate your next move in this otherwise quite hectic combat system. From the menu, you can use items, abilities, and magic spells—the expected—but also issue all those same commands to characters you don’t control. And this is where the tactical aspects of FFVII’s combat system come into play. Overall this fusion works very well.

Since you can take active control over characters, the way combat roles work shifted. Instead of characters having somewhat predetermined roles in combat—healer, damage-dealer, and so on—every character is a good base fighter who is fun to control. For example, Aerith, another character that joins your party, got originally funnelled quite heavily to be a healer or a spell caster because her physical capabilities are terrible. In the remake, she is a competent base fighter from the get-go, very useful, as her attacks are ranged and very fun to control.

Characters now entirely specialise through Materia, which go into the designated slots of your character’s equipment. Materia can give a character either passive abilities or spells to cast. This is great because it allows you to pursue your dream party of characters. What is also fantastic about this is that when integral party members are taken away from you for story reasons, with a bit of Materia juggling in the equipment menu, you can restore the missing character’s functionality for your party. However, since that substitute characters likely won’t have the same sum of Materia slots across their equipment, it also encourages experimentation. If you have to make do with less, what do you really need? If you have more, what Materia do you want to try out?

Another novelty that encourages experimentation is the many different weapons the characters can equip. Many of them feel very different, as each one comes with a unique ability. The twist is that each weapon gives you a sort of combat mini-quest to attain mastery over the weapon. Such mastery allows you to keep the ability even when equipped with a different weapon. This has two benefits. For one, the given mini-quest can guide you in using the weapon effectively because the tasks always require you to do the weapon’s unique thing. And secondly—as mentioned before— it encourages experimentation. It is a common problem in RPGs that you effectively get locked into a character build simply because you have used that build for a while, levelled up all your equipment and so on. However, when you eventually find something new that you would like to try, you would have to start from zero all over again. This discourages experimentation over the course of a game because so much about your character is effectively set in stone. The more you go on the less likely you are to switch things up. Final Fantasy VII Remake cleverly avoids this problem.

However, the one major issue I have with this new combat system is that the damage that you receive in battle stays when it is over. Now, this is of course how it was in the original, but since so many things were changed about the combat system for this remake, being conservative here has negative consequences.

Having to heal after many encounters so that you are prepared for the next one slows down the game. While this was passable in the original since the combat system was also passive, in the remake, once the engaging action is over, things grind to a halt as you have to navigate menus to your healing items and spells. And unlike using the menu in combat, the strategic component is absent. It’s just tedious. And it gets more and more tedious as the game goes on because with time your inventory holds many low potency healing items, which are of little use in combat beyond a certain point. So if you want to be efficient, you use these items outside of combat, making the regular healing ritual even slower.

It seems like the developers noticed this as well because, towards the end, you will increasingly see more benches in the areas you explore. These are for fully healing your party for free. It does soften the impact of this issue but much too late and too little. So while the devs took precautions for the healing ritual not to escalate too much, it’s still annoying.

Conclusion

Final Fantasy VII Remake is everything a Remake should be and goes even beyond that. It greatly extends a gaming classic thematically, narratively, politically and gameplay-wise. It is self-aware of the cultural impact of the original game, but it is also not afraid of bold divergences, especially at the end.

The fusion the remake provides of Final Fantasy XV’s combat system and Final Fantasy VII’s traditional Action Time Battle is largely a success. But the unfitting health-management approach does dampen the action quite a bit.

Overall, this is brilliant, and whatever the follow-up to this remake will be, I’ll be eagerly awaiting it.

9/10

Hotline Miami 2 is easily one of the most remarkable instances of creators trolling their own fan base. This game is notorious for not living up to the expectations set by its predecessor. Yet, I don’t believe that this game is a failure of game creation but instead has been deliberately constructed to be the way it is. To understand why we have to look at what came before HM2.

Context

Hotline Miami is a hugely celebrated action game from 2012. It’s a simple and self-contained game. Split into several levels, you play as an on-demand hitman who goes to the places left on his answering machine and commits a massacre. These killing sprees make up the core gameplay loop. From a top-down view you move through the levels and kill dozens of people to an aggressive electronic soundtrack—beating them, slashing them, shooting them. The violence is visceral, blood goes everywhere, and feedback is immediate. It’s addicting.

However, when you’ve killed everyone, the music stops abruptly, and the game has you walking back through the level to your car—walking through the pools of blood and corpses you created. In this simple way, the game traps the player in addictive violence but then suddenly pauses and asks you to reflect on what you just did. The commentary on violent action games is obvious. And with, at the time, massively popular shooter series like Call of Duty and Battlefield loving to employ the trope of the Russian villain, the fact that the people you are killing are part of a Russian gang is probably not a coincidence. And I have to admit that killing people in this game is a tonne of fun. Hotline Miami triumphs in its simplicity.

It is then very unfortunate, that this game acquired a fandom that absolutely loved the violence and obsessed over the game’s obscure plot while closing their eyes to the game’s actual message. This is the group of people that Hotline Miami 2 seeks to troll.

Sequel

Hotline Miami 2 is a sequel for the fans of the original game in the bluntest form. People liked the combat? We need bigger levels, more violence, and more play styles! People loved the obscure story? Let’s give them more characters, elaborate backstories for those from the original, and a non-linearly told story that’s gonna take some real puzzle-solving to crack! It’s designed to deliver the fans of the original an overdose of the same.

Explaining sequels like this as the result of lacking creativity or as a cynical cash grab might be tempting, but it’s just not the case here. The creators proved their creativity and game design abilities with the original Hotline Miami. And on top of that, the creative leads, Jonathan Söderström and Dennis Wedin didn’t change between the two projects. And lastly, there is significantly more effort put into this game than the predecessor, which is clear to see. It seems very unlikely then that this is just a way of cashing in for the devs.

The elimination of these possibilities and looking at the game’s contents make me believe it is trolling—an artistic statement on their relationship with their fandom.

Story

Hotline Miami 2’s story is completely incomprehensible in the way it is told. And on top of that, once you partially decipher what is going on, the story is plainly ridiculous.

The game’s overall presentation isn’t very helpful in making the player understand what is going on. The whole experience is styled after movies. The game is split into “acts”, which are subdivided into “scenes”, which you select from a menu of VHS tapes. The multiple timelines in the narrative are jumped between by, of course, rewinding and fast-forwarding the tape. And to really mess with you within the game’s narrative, there is an actual movie being filmed. You act out some of its scenes, which are often indistinguishable from things that actually happen within the game world.

But somehow, it gets even more convoluted once the game introduces its backstory in act three. Apparently, the USA and USSR fought a war against each other on Hawaii. The conflict was brought to an end with a nuclear first strike by the Soviets. And this is why Russians are hated so much in this world. That’s certainly one way of addressing that question. If that sounds ridiculous to you, it should! It certainly does to me. It’s the point where you should realise that the creators are messing with you.

I would usually not feel comfortable just blankly calling an entire game trolling like this. It would be bad for criticism if just everything that is contradictory or seems ridiculous could be written off as mere trolling. So how is this game different?

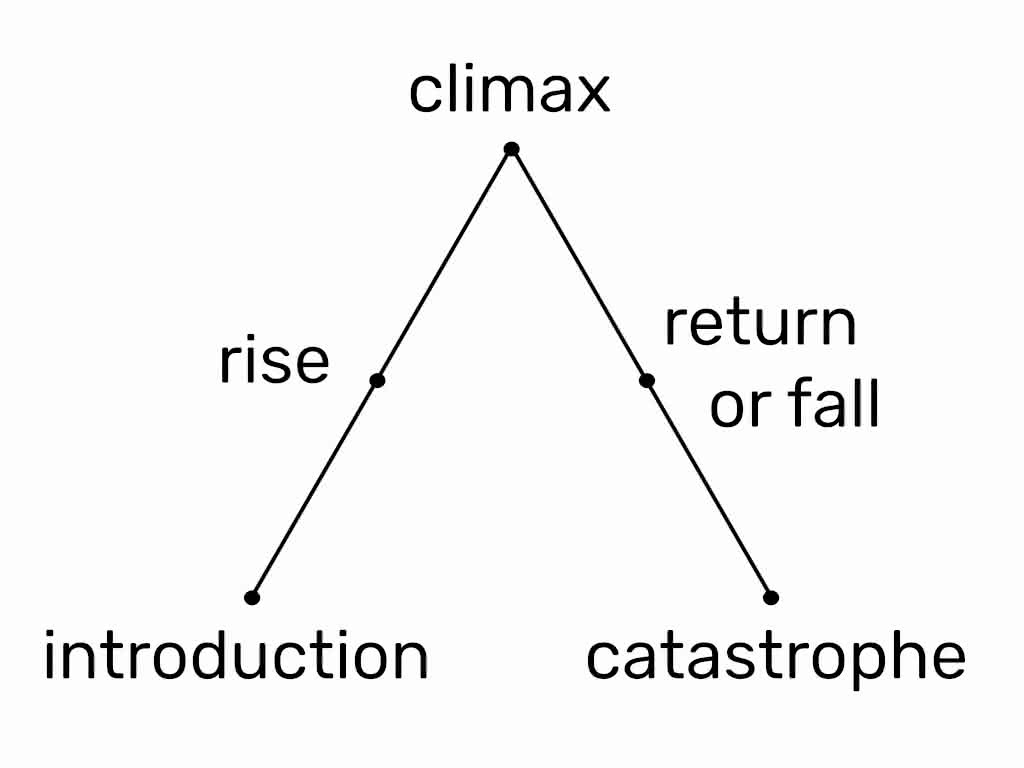

Besides the ridiculousness of the setting, and specific story moments that attempt a critical commentary on Hotline Miami’s fandom, the creators themselves don’t seem to have much respect for their own work on this game. The most obvious point would be how, at the end, the entire world is destroyed. Everything was told and set up for nothing, it appears. But there is an even clearer indicator. The game’s acts in chronological order are called: Exposition, Rising, Climax, Falling, Intermission and Catastrophe. Except for Intermission, these are exactly the generic names for the acts in the five-act structure of a drama. In fact, it’s so generic, here is an illustration of this structure I found on Wikipedia:

(Credit: SinjoroFoster. Public domain.)

While, clearly, a lot of writing effort went into this game, it’s not presented with a lot of heart. Combined with story moments that seemingly only exist to frustrate and confuse those that actually want to engage with the story, I think the case for this game being trolling is very straightforward. However, some moments do make sense if we understand them as commentary on the trolled audience. This goes for both the people that uncritically enjoyed the original‘s violence and those that obsessed over lore so much they missed the game’s actual point.

Hotline Miami 2 features a long list of characters that you play as. A lot, if not all, of these characters, are a meta-commentary on the game’s fandom. It highlights different nasty elements of that group.

The most obvious meta-commentary lies with a group of people that took inspiration from the player character in the original Hotline Miami for their streaks of mass murder. Like him, they wear different animal masks, but here they do all the time, unlike in HM, where they were only put on directly before a massacre. And just in case you didn’t get it, the game refers to this group as “The Fans” in its Achievements.

The Fans, unsurprisingly, kill for fun. Their final killing spree happens at the end of act three. Here you play as each one wiping out a floor of the building while an aggressive house track plays in the background. This is where all the people who The Fans represent get what they want. Except, at the end of the level, they all unceremoniously die. While the original game ends with some moral ambiguity, as the main character exacts his revenge on the mafia and triumphantly lights a cigarette, there is no justification or glory here.

Another character that loves the violence he’s enacting is a literal neo-Nazi. With the original‘s hints of ultra-nationalism (if you refuse to engage with metaphor), it’s not surprising that it appealed to a certain audience. You’re introduced to him as he shaves his head in the bathroom, and the moment you go into his living room, you immediately notice the flag of the Confederacy that is lying on his sofa like a blanket. After you are done carrying out his hateful killing, he tries to get a tattoo to celebrate the occasion but fails because he didn’t schedule an appointment. Here the creators are telling their Nazi fans to piss off, by showing them someone they can identify with and having him be a sad and pathetic loser.

Meta-commentary of the game extends beyond just commenting on the killing, however. Hotline Miami 2 starts out with a scene of sexual assault, where a murdering creep goes after a woman he thinks is his girlfriend. Initially, this looks like senseless provocation, but there’s more to it. You see, this scene is part of a film being filmed within the game’s narrative, which was inspired by the happenings of Hotline Miami. The actress, playing the victim in this scene, has a strong resemblance with a woman the main character in HM saves from the mafia. Actually, there is no clear indication that he is saving her. It might just as well have been a kidnapping. Either way, the woman lives with the main character from there on out. It’s not hard to imagine that this decision wasn’t entirely enthusiastic, or even a choice at all, considering the main character is a serial killer.

The movie plot in HM2 is a commentary on how not a lot of people got that you weren’t exactly a knight in shining armour in the original game. In a later scene, the creep is arrested because the woman reported him to the police. In the following level, you murder your way through the police station to where she is being interviewed. On entering the room, she shoots you and screams: “I am not your fucking girlfriend!” It’s clear what is being said here. And, again, just in case you didn’t get it, in the first level, where you play as one of the Fans, you are tasked with bringing the sister of another Fan home from a gang. You do what you do best—murder your way through to her—but she doesn’t want to go with you. You just murdered all her friends. Distressed and with a gun in her hands, she tells you to leave her and go. If you don’t listen and get closer, she shoots you, and you have to do the floor all over again. You get punished for not having learned your lesson.

Finally, the game’s story is a massive middle finger to those that obsessed over the original game’s lore while disregarding any of the game’s use of metaphor and allegory. This goes beyond the back story about the hot war between the USA and USSR being totally ridiculous. While the game gives these people a hugely convoluted story to unravel, it is all for nothing in the end. The game finishes in an outright nuclear war between the superpowers, using their capacity for mutually assured destruction to reduce the game world to ash.

Over the credits, you watch as every character that was introduced in the series (and is still alive) dying in a nuclear blast—one after the other. Did you have fun putting all the puzzle pieces together? Well, it’s gone now.

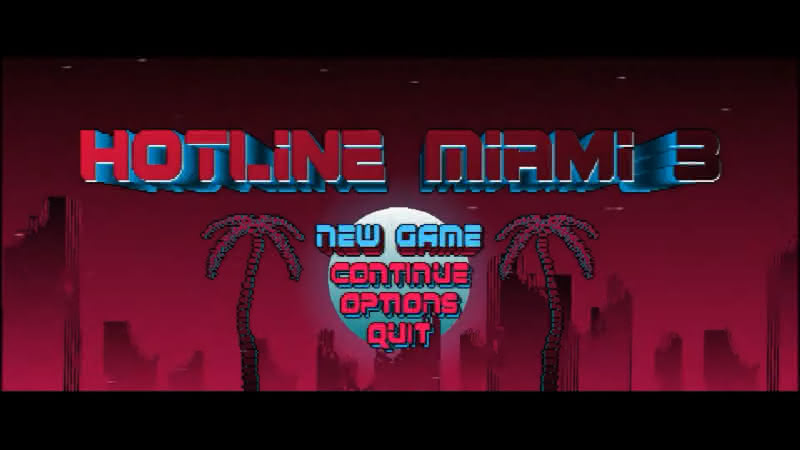

The final image you see of the game is the fictional start screen of “Hotline Miami 3”. In the background, you can see the ruins of the Floridian city. Of course, there is no narrative comeback from an ending like this. It’s not supposed to be an exciting teaser for another instalment in the Hotline Miami series. Instead, what it is doing is asking a question. You’ve just played through the sequel to Hotline Miami. How does the idea of another sequel make you feel?

(Credit: Dennaton Games. Fair use.)

There is a mean-spiritedness to this all. The game uses metaphor and allegory to make fun of and comment on the people who didn’t get that about the original. Pulling the story into the ridiculous and referencing characters from the original isn’t going to make them realise anything—it will all just seem like an even greater puzzle to unravel. While those who get it laugh at them, they do in-depth theory crafting for a game that showed them the finger, but, of course, they didn’t recognise it as such. And looking at the wiki articles and lore videos made for this game, it seems like that’s exactly what happened. Hotline Miami 2 could have tried to communicate how many got the original wrong but instead reads much more like the self-indulgent product of pure spite.

Gameplay

The gameplay in this game is not all that interesting because, except for some superficial additions, it is largely unaltered from the original. The music still stops abruptly after you are finished killing everyone. It’s still the same trial and error per level. You step-by-step uncover the best strategy for getting through it consistently with the twist that the enemies have slightly different weapons on every attempt, so you always have to improvise somewhat.

While the story is fully developed with a clear through-line of what it is doing, the gameplay makes Hotline Miami 2 feel a lot more like the misguided sequel that many people think it is. The game now features a wide cast of characters—each with their own unique traits. And further, new enemy types. But what really sticks out is the difficulty.

The game is immediately more difficult than its predecessor. While the first level in Hotline Miami featured only goons with melee weapons to get you accustomed to how the game plays in a manageable way, in Hotline Miami 2, the first enemy in the first proper level has a gun. And not just the one. There are many more of them with wide-open spaces and corridors for you to get shot from off-screen. The difficulty escalates more quickly too. In level three, you can already not trust walls and corners anymore because there are windows everywhere for you to get shot through.

The primary factor in Hotline Miami 2’s higher difficulty are the much larger levels. Because as there are more things, more things vary and can go wrong. Beyond that, the levels are so big that enemies triggered by a gunshot can take up to 15-20 seconds to get to you from areas of the floor you weren’t even looking at, catching you off guard.

But ultimately, this is tame in comparison to the story. It’s a somewhat more difficult and frustrating version of the original with some easy additions that one would expect from a sequel. The ridiculous tones of the story really don’t shine through here. The gameplay would have been the prime place to further the meta-commentary already present. But for whatever reason, this aspect of Hotline Miami stays relatively untouched. The core gameplay sections just being more frustrating is a huge missed opportunity. Despite being harder, it’s nothing you couldn’t get accustomed to. With enough trial and error, you will be able to triumph over this game’s difficulty. And that’s the problem: the gameplay does not challange this way of engagement. It could have been a great way to complement the messaging of the story with the core component of Hotline Miami, the violence. But instead, it settles for, arguably, giving the fans it set out to troll precisely what they wanted.

Conclusion

Hotline Miami 2 is a very fascinating game. The trolling aspects make for intriguing creator-fandom dynamics, but the game being unwilling to touch its own gameplay for that purpose undercuts it significantly. The primary interactive component of HM2 being a more-frustrating-but-nothing-more experience is very disappointing.

The game’s trolling has some great isolated high points, but, in my opinion, the game didn’t go nearly far enough.

5/10

Picross is a long-running Nintendo games series that revolves around solving Nonograms, a popular Japanese logic puzzle. The series has been so influential in the popularisation of Nonograms that many people only know them by that name. The puzzle requires filling a grid according to sequences of numbers on the side. Each row and column on the grid has such a number sequence. Following the rules, a cell in the grid is either filled or left empty. Once done, they form a picture.

It’s somewhat similar to another popular Japanese logic puzzle, Sudoku, in that it offers practically infinite puzzle variations and a simple set of rules to complete a puzzle. But contrary to Sudoku, where you have to choose a number ranging from one to nine to fill a cell, for Nonograms, the choice is binary. It is a much simpler type of puzzle in comparison. But in turn, it gains some flexibility. For Sudoku, the grid is fixed in size, whereas Nonograms have arbitrary width and height.

The way I play these two puzzle games totally differs, however. A Sudoku puzzle can be hard to crack, and it is fun spending minutes eliminating possibilities until you’ve found a progression path. With Nonograms, it is the most fun trying to solve them as fast as possible. The significantly easier ruleset allows for this. And with filling a grid cell being a binary choice, it is much easier digitised to a simple button press than Sudoku is. Everything about Picross lends itself to this fast playstyle, and it is a tonne of fun.

With this introduction out of the way, let’s talk about the actual game this review is about.

The actual game

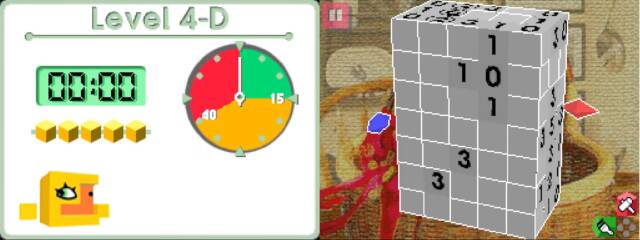

Picross 3D is HAL Laboratory’s attempt at extending this two-dimensional puzzle classic by another dimension. Instead of a grid of cells, you start with a cube that subdivides into many smaller cubes. And instead of constructing a pixel image, you form a voxel sculpture out of the cube.

With this, you can’t really have sequences of numbers on the side. So for this game, it is simplified to one number per line. Although, it’s not quite that simple. Sometimes a number has a modifier, indicated by having the number painted within a square or circle. The number tells you how many consecutive blocks in the line remain part of the final sculpture, and the modifiers tell you how many gaps are allowed in the sequence of blocks.

The game primarily uses the Nintendo DS’s touchscreen for controls. Whereas with other Picross games on the platform, touchscreen controls were optional, here they are mandatory. With the stylus, you rotate the puzzle to look at it from all directions. It works the same with marking cubes to be kept or destroying them.

One nice thing, that differs from how Picross usually works, is that cubes that are marked to be kept cannot be destroyed without unmarking them first. This is great, as the risk of misclicking is high, especially on larger puzzles. It shows that a lot of consideration went into how this game differs from the rest of the series and how its unique qualities necessitate certain things to be different.

Since the puzzle is in 3D, you also have to have the ability to look inside the puzzle, to see things that would be otherwise obscured by other cubes. For this, you can slice the puzzle along the three axes to get a cross-section.

Another unique thing about this game is that it features a rating system. On completion, you can earn up to three stars. One star is always guaranteed. You get another if you solve the puzzle under a certain time threshold. And the final one is earned for not making any mistakes.

The game is broken down into levels that contain a collection of puzzles, and you can advance to the next level after collecting a certain amount of stars.

The other major distinguishing factor of the game is its aesthetics. Picross games are usually quite stylistically plain. This game has a much more distinct visual identity. It features a mascot that is a cube with a face on it that makes celebratory dances as you solve puzzles.

A newly started puzzle with the game’s mascot in the bottom-left. (Credit: HAL Laboratory. Fair use.)

What it feels like

The addition of another dimension to a 2D puzzle game sounds simple enough, but here, it significantly shifts the overall game feel. What was added in terms of complexity was trimmed elsewhere in turn. For example, there might be lines going into three different directions now, but each can only feature one number, instead of multiple, like in classical Picross. The overall logical complexity is similar but achieved through different means. These differences have further side effects on the gameplay beyond just the new controls.

Picross 3D plays very differently from classical Picross, in that the act of solving is much more slow and deliberate. The three-dimensional nature of the puzzles results in you never seeing the whole puzzle at once. Realistically, you can only look at two dimensions at once while solving. In practice, this results in a constant shifting between the three dimensions.

The controls also foster a more deliberate playstyle. Because of the 3D perspective, the cubes heavily vary in size and shape due to their projection onto a 2D screen. This makes misclicking very easy, and thus you have to go slow to avoid mistakes.

The game further incentivises methodical play with its rating system. Making mistakes in this game is easier than ever, and if you make one, a star will be subtracted from your three-star rating.

With all that said, you can probably see that my usual way of playing Picross is on a collision course with this game.

What I don’t like

The required deliberateness during puzzle solving results in a lot of downtime, where you aren’t as much solving a puzzle as you are searching for the next line to advance on. Standard Picross has this too, to an extent. But since you have a full view of the puzzle at all times, downtime due to searching is much smaller. This is especially true once you realise the locality principle to solving standard Picross. When you progress on a line, the corresponding row or column orthogonal to it is also affected, and most of the time, you can directly progress from there. Thus it forms a chain of actions with minimal downtime. As a result, this lends itself to playing the game quickly and is a tonne of fun. And this is the problem with Picross 3D. The puzzles aren’t more challenging, but, due to their 3D nature, are slower to solve. Thus it removes the integral fun component for solving Picross for me and, unfortunately, doesn’t add anything to replace it. The greater emphasis on visual style was enough to keep me playing initially, but after several hours that wore off. After that, the game was just a slog to play.

Furthermore, I have several technical complaints. Once you get into the later stages of the game, the puzzles get big and quite unwieldy. The puzzles take up the entire screen, and looking at multiple dimensions simultaneously, requires you to shift your view around constantly to see what goes over the edges of the screen. The puzzle slicing is even worse. Slicing the puzzle to see only parts of it resizes it on screen accordingly. This produces the problem that when you slice in, the game zooms in, but once you want to slice out, due to the zoom, the point you would have to reach to slice out fully is out of the frame. You have to slice out as far as the screen allows for and redo the motion until you are done. And because of the size of the puzzles, you have to do slicing like this constantly. It’s very annoying.

And again, on larger puzzles, there are severe issues with aliasing, which makes numbers hard to read at certain angles.

Conclusion

Picross 3D seems like a natural and simple extension of standard Picross, but that assumption would be wrong. Bringing Picross to the third dimension significantly alters the gameplay. So much so that it removes why I play Picross in the first place.

The larger puzzles are especially problematic. Not only are the base problems further exacerbated by them, but the game doesn’t even appear to be built to deal with the sheer volume of cubes that make up those puzzles. They make the case that bigger isn’t necessarily better — sometimes it’s just bigger.

4/10

The Great Ace Attorney Adventures is the first game in a spin-off series from the modern classic Ace Attorney series of games built around criminal cases and court drama.

It differs mainly in that, as opposed to the rest of the series, it isn’t set in contemporary times, but during the late 19th century in Meiji period Japan and the British Empire.

You take on the role of Japanese Student Ryunosuke Naruhodo, who, after successfully battling himself out of the court for a crime he didn’t commit, goes abroad to the British Empire to study the British law and judicial system. Ryunosuke isn’t a law student, so this doubles as his journey of becoming a lawyer.

What the spin-off affords the game

The spin-off affords many exciting opportunities, but, of course, also challenges.

The game essentially being a clean slate allows for a sharp departure from the established series canon. The completely new cast of characters is the most obvious example.

Another such example is the soundtrack. Prior games in the series heavily relied on previously established melodies and themes. Those were usually either reused directly from previous games or arranged for jumping from one console generation to the next. The Great Ace Attorney features a completely original and orchestrated soundtrack. It sounds great, and it fits the period the game is depicting. But in my opinion, much more importantly, it helps the game establish an identity of its own.

The historical setting has also been used in a few compelling ways. So far, the series hadn’t made historical references at all. This was further complicated by the English localisation of the series changing the setting from Japan to the USA. Now, however, the game is brimming with historical references and factoids about late 19th century Japan and England. The game references laws from the time, local buildings in England such as the Old Bailey court, and famous historical figures like the Japanese author Sōseki Natsume.

New faces, old faces

While the game features a compelling original cast of characters, they largely fall into familiar archetypes.

The protagonist, Ryunosuke Naruhodo, comes very naturally after Phoenix Wright from the main series. He is determined and brave but also despairs easily in stressful situations in the courtroom. In Ryunosuke’s case, though, that character flaw is more understandable since he never studied to become a lawyer.

Susato Mikotoba is Ryunosuke’s judicial assistant. She clearly comes after Maya Fey from the main series, though not as playful. The charming, witty and empathetic character will be familiar to anyone who has played the original trilogy. On top of that, she is also quite assertive and forceful at times. I like her a lot, but I cannot help but see the missed opportunity for a female lead character here. The main series attempted to bring a female character to the cast of protagonists, but this was, for the most part, isolated to one case and neglected in the following release.

This game provided a clean slate, so the trouble of having to integrate a new character into a cast of well-known ones would have been avoided. And if you would have me believe that the British state would permit a foreigner with no formal education to work as a lawyer, why not a woman?

Our new pair of protagonists. (Credit: Capcom. Fair use.)

Two characters that defy previous archetypes in the series are Herlock Sholmes (yes, you read that correctly) and Iris Wilson. With a game set in Victorian London, the Sherlock Holmes character is a must, of course. Herlock is the same unstable genius we know from many stories in his young years. However, his deduction skills are not as good as the popular stories usually depict. He frequently gets small details wrong, and you’ll have a fun time correcting those mistakes. This twist is nice and, clearly, Sholmes is supposed to be one of the stars of the game, but I find the character of his assistant, Iris Wilson, much more interesting.

Iris Wilson is far more than just a gender swap for Dr Watson. She is a child prodigy, inventor, and chronicler of Sholmes’ adventures. At just ten years of age, Sholmes acts as her adoptive father of sorts, but she comes across as much more mature than him. She is charming and intelligent, and I’m sad we only see so little of her in this game.

As opposed to Herlock, who is a synthesis of the many different renditions the character has seen in fiction, Iris is almost completely original. Sholmes is what you would expect, but the only thing of Watson that remains in Wilson is that she is the chronicler of his adventures and that they live together.

The final character that sticks out is the series-typical prosecutor: Lord van Zieks. He is pale and dressed like an English aristocrat. This makes him look like a vampire and the game heavily leans into that. He absorbs the entire courtroom with his assertive personality every time it’s his turn to speak. His theme that prominently features a harpsichord and hits you like a brick wall of sound really sells those moments.

Van Zieks is very fun to watch. He often plays around with a wine glass of his: filling it, drinking from it, tossing it, or crushing it—I certainly appreciate the Castlevania references. He makes for a top contender for Top Prosecutor in the series, and that’s a title with tough competition.

Overall I’m happy with these new characters, but also a bit sad that largely the game falls back on established tropes instead of trying new things like with Sholmes and Wilson. This instance of a spin-off would have been the perfect moment to do it.

Old themes extended and revised

The Great Ace Attorney Adventures doesn’t waste this opportunity of a new beginning by just continuing the themes of the series and leaving it at that. Entirely new thematic strands are being explored here.

For one, the series, thus far, explored several issues in the legal system, often in the hyperbolic way. We are to understand that the justice system is not just at all. It is never explained, however, how it came to be that way. That is where this game comes in.

The Great Ace Attorney Adventures explores how the Japanese legal system was formed during the Meiji period of liberalisation and how it was greatly inspired by the legal system of the British Empire. When Ryunosuke goes abroad to London, we see many of the same issues already present. It’s very interesting to see this unfold, and it gives this game the fresh coating you would expect from a spin-off.

Certain aspects of the British Empire are greatly emphasised, even caricatured at times, to deliver an image of Britain that reflects Japanese views of it at the time. One such heavily emphasised thing is the technological superiority of the British Empire. The Japanese Empire, in its pursuit of liberalisation, sought to partially imitate the British Empire. As such, Japan is seen as technologically unadvanced, and one looks with marvel at the technological achievements of the British.

When our protagonists arrive in London, they speak at lengths about how different and greater everything is. The first interaction with the British legal system leads them to the office of the Lord Chief Justice, where a huge mechanical construct of gears looms in the background. While that is architecturally impractical and would make for a terrible place to do office work in, it drives home the message the game is trying to convey very efficiently.

The game does not solely portray British society as superior it also makes it clear that they see themselves that way. This leads to broaching the issue of the open white supremacy of Europe at the time. There are a lot of instances where racial prejudice is directed at the Japanese characters in this game. While certainly unpleasant, it obviously has its place in a game making historical commentary. But I can’t say that I care much about this aspect. It boils down to the Japanese characters taking the racist abuse and later proving the person making racist remarks wrong. This happens by showing their competency, or that they possess a positive character trait that contradicts the stereotype. I really dislike this because would the racism have been fine if the racist stereotype was confirmed in that instance? It makes for shallow commentary, that’s it.

Beyond that, another interesting component of the game is the jury. A group of six London citizens, chosen at random to decide the verdict. The game portrays these people as impulsive and easily swayed, effectively showing that involvement of the public like this doesn’t make for a better justice system.

This is interesting because in Apollo Justice: Ace Attorney, the “Jurist System” is presented as the solution to the game’s final conflict. This is not necessarily a contradiction, even though it might appear at first that the expressed opinions have changed here. The series often times shows your protagonists subverting, or outright breaking the law to peruse legal justice in this series. Clearly, that wouldn’t make for a great legal system. And yet these actions are shown as essential to deliver justice. The way this looks to me is that the game is saying that no justice system is capable of delivering justice in all cases. It might have previously looked like advocacy for a jury system, but this game clearly rejects that.

The game also continues the theme of belief in the justice system being like a religion. The Old Bailey courtroom looks very similar to the insides of a church with its stained glass windows. That house never had windows like that, but one would be missing the point if one were to criticise the game for not being historically accurate. In Gyakuten Kenji 2, the windows of the high prosecutorial office were styled similarly. Clearly, the game is connecting itself with this broader established theme. Though that connection is much thinner than in previous titles. Gyakuten Kenji 2 features the topic much more prominently, and Ace Attorney: Spirit of Justice, released one year after this one, made it the entire premise of the game, so I am not complaining.

There are other moments in the game that felt like they were commenting on previous titles in the series. Most noticeably, when the game makes you defend a guilty person, similarly to Justice for All. Except here, it isn’t the big revelation at the end of the game, but instead, it is used to build a story of betrayal and trust. The game gives you a case that violates your trust, and in a later case builds that trust back up again.

The big difference between the two clients used to tell the story is wealth. While your wealthy client uses you as a pawn to cheat the system, the other person is poor and has no one to put their faith into. The game’s message is clear: it is the poor people that need your help in this system, not the wealthy. I like this because it is much more in line with the identity the games developed over the years and ask much more interesting moral questions than: “But what if you defend a murderer?”

The gameplay additions

By now it should be clear, how this spin-off does take some new directions, but mostly tries to stay faithful to the core of the series. The gameplay is no different.

Largely the game follows the same gameplay tropes as the rest of the series and the additional court room mechanics from Professor Layton vs. Phoenix Wright: Ace Attorney. This means multiple people can and almost always will testify simultaneously. Along with that, there are “Pursuits”, which are essentially ways of furthering the cross-examination by pressing other witnesses on the bench for their thoughts on the current statement. I’m happy these are back and are allowed to shine in a proper Ace Attorney game and not just a crossover.

A new addition to courtroom sections comes with the jury. When the jury unanimously advocates for a guilty verdict, you get the chance to examine the jury’s grounds for doing so. These jury examinations function similarly to cross-examinations. Each juror presents their reasoning as a statemented. But unlike cross-examinations, your goal isn’t to uncover a lie, but to change the juror’s mind to prolong the trial. You do this by pitting contradictory statements by two jurors against each other.

The jury examinations introduce a new dynamic into the court room, because the way you would usually progress in such a section is by presenting evidence, but here it exclusively works with the statements themselves. This isn’t entirely new, though. In a previous game, there was an instance of having to press statements during a cross-examination multiple times in a specific order, to uncover the underlying contradiction. This didn’t work well however, because up until that point, you only ever had to press statements once.

Now, this idea was given its own feature and works much better that way. It makes for a welcome change of pace during court sections and you get to see more action from your main character, instead of a constant back-and-forth with the prosecution.

The other big feature that was added to exploration and examination sections are moments of so-called “Joint Reasoning”, where Ryunosuke joins intellectual forces with Sholmes. The detective may be world famous for his deduction skills, but in reality he often times gets crucial details wrong, even though his intuition leads him mostly on the right path. That’s where you as Ryunosuke come in. You get to identify and correct the small details Sholmes got wrong, to produce a properly useful deduction. This, again, is a bit like cross-examinations. You stop at a statement made by Sholmes and then try to figure out what he got wrong and present your own version of his statement. This usually involves looking around the environment for clues or presenting evidence from the court record.

All of this is presented in a very flashy and lively way. It almost feels alien to see characters move around so much on screen. Here the series is truly reaping the benefits transitioning to 3D.

It’s fun to watch, though the setup for it is bit longer than it needs to be in my opinion. But beyond that, it introduces some of the drama of the court room into the more calm exploration sections, which, just like the jury examinations, makes for a nice change of pace.

Sharply uphill, with rough decline

So far, I’ve been almost exclusively positive about this game. I really want to impress on you, how many good things this game has going for it. Other games in the series achieved great things with less. It is then a huge disappointment that a lot of this potential remains unused.

All of the great things I talked about so far get completely overshadows by the game’s poor pacing and structure. I will say, the game has a strong start, arguably the best in the entire series. Ryunosuke having to defend himself as a layperson in a case of high national interest immediately puts the stakes high. In the next case you get some breathing room with a pure investigation case. The game cleverly uses that time to introduce Sholmes and for you to learn about your soon to be judicial assistant, Susato.

It’s also a good setup for the next case which for balance, you’ll be spending entirely in court. Here the game also does a lot. It has to introduce the unique elements of the British justice system and introduce you to several new characters, including the new prosecutor van Zieks. At the same time, it’s the one chance Ryunosuke gets to prove his competency as an untrained lawyer. And further, the game makes you slowly realise that your client is a monster, who has deceived you into helping him in his scheme to cheat the justice system.

This makes for the climax of the game. It feels great up until that point, but after this there are two more cases. The one that follows is a lot slower, so you can recover from what came before. And the final case attempts to be the finale of the game, like is tradition for Ace Attorney. I say “attempt”, because it employs all the usual tropes to signal that the stakes are high, and even hints at the possibility of a conspiracy within the police. But all of this on reveal deflates to nothing. I cannot express just how disappointing that is.

I am not opposed to the third case being the high point of the game. It would be perfectly fine for this game and its sequel The Great Ace Attorney Resolve to play like one big game split into two, with the latter half of the first game properly preparing you for what will come in the second game.

To some extent, the game does do this. For example, it introduces you to Iris Wilson who no doubt, will have a huge role to play in the sequel, but then the game gets trapped in trying to deliver the typical Ace Attorney experience with a huge final case. But what is there just doesn’t live up to it.

In the end, there is a lot of hasty setup for a sequel, which leaves a sour taste in my mouth. It feels like the game saying that in the sequel, maybe, there is going to be an actually satisfying conclusion. All of this could have been avoided by not setting the expectations like that.

I am sure, that in that case, I would have finished this game much more satisfied.

Conclusion

The Great Ace Attorney Adventures has a lot of very interesting aspects to it. But unfortunately a lot of that potential is squandered by the game’s pacing and structure, which is terrible for a game that is part Adventure, part Visual Novel.

The first half of the game remains very good, even after finishing on a sour note. It makes you yearn for this game with the pacing issues absent.

Overall I can’t say this game is all that worth playing on its own. Especially not when there are so many other great games to choose from in this series. I hope that with all the build-up for the sequel, it turns out better than this game.

6/10

We. The Revolution is a fictionalised historical drama set during the Reign of Terror in revolutionary France. You play as an upstart judge, and with your ruling power, you will decide over life and death. Who is innocent? Who is counter-revolutionary? Who goes free? Who gets sent to the gallows?

During these uncertain times, you want to make it big, but you also have to protect your family, and yourself, of course.

The daily routine

The core gameplay loop revolves around different tasks that you have to do every day. You usually start with judging over a case in court, part-take in the execution (if that was your ruling), and manage relations with your family and friends. This is interspersed with the occasional story event. And over time, the daily routine gets more complicated. After a while, you even command a militia to defend and expand your territory within Paris. You even get the ability to plan conspiracies against your competitors for power over the city.

The court sessions are clearly the main attraction. You are given an investigation report regarding the person on trial. From this report, you can use the contained clues to unlock and extract statements from the defendant or a witness. Interestingly, you can choose which statements to pursue, and different ones will influence the jury’s opinion of the case. Theoretically, you could convince the jury that a totally guilty person is actually innocent just by choosing all the statements that paint them in a positive light.

Different sections of Parisian society will have expectations regarding your rulings. You will have to balance the goodwill of your family, the common people, the revolutionaries, and the aristocracy. If a faction gets too displeased with you, they’ll send an assassin after you—game over.

These groups are almost always at odds. There comes a point in the game where you always calculate the ramifications of your ruling beyond the defendant’s actual guilt. This is one of the very intriguing elements of the game. It shows you how you are just as much politician as other characters in the game, even though you are a judge by profession.

The brief good moments

Warning: The text below contains spoilers.

There are some great moments at the beginning of the game. They come about by the developers cleverly using established mechanics/moments in the game.

During chapter one, every time you let the guillotine blade fall, there is a gruesome scene afterwards, where a blood-soaked blade is strung up again, slowly overlooking a shocked crowd of spectators. Once chapter one ends, that scene is gone. The executions haven’t stopped—they have just become so commonplace they seize to be shocking.

Another such moment is when your son is murdered, you’ll receive a huge stack of condolence letters the day after on your desk during the trial.

Also great is when it is announced that imprisonment is not an option for punishment any more. Your options for rulings at this point are only freedom or the guillotine.

These small moments work well, and it is all the more intriguing to see how you climb the hierarchy of power in the game over time as your rivals get eliminated (often by you)—really showing how the Reign of Terror got its name. However, it is a shame how few of these moments are in the game overall—actually, I pretty much named them all.

Everything else

Huge parts of this game are clearly inspired by Papers, Please, which I remember as a focused and fun exploration of the game’s setting by playing a bureaucratic cog in the machine. We. The Revolution is not that. More and more responsibilities get added over time until the court sections seem like just another side attraction. It’s very unfortunate because while they don’t have much depth, they are the most interesting and deep aspect of the game. But as time goes on, you will spend more of it on positioning your militia on the map, convincing others to aid you in your conspiracies, and so on.

Over the hours of sticking with the game, I gradually lost interest. Once chapter three came about, I quit. The narrative revelation at the end of chapter two was simply not enough to keep me playing.

The only other positive thing that I can say about this game is that its art style is striking and fitting. Pixel art seems to be exhausted in its aesthetic capabilities at this point, so this mosaic art style was genuinely refreshing and looked great. It gives the game a simultaneously sharp but abstract look. Very fitting, I think, and I hope more games will use it in the future.

(Credit: Klabater/Polyslash. Fair use.)

Otherwise, the game gets bogged down by many weird technical issues. The game plays like a not so great mobile port. In fact, most moments in the game seem almost designed for a touch screen. I was surprised to find out this game wasn’t released on the iPad or a similar platform.

The game takes quite a bit of time to transition from one part of the daily routine to another, when really, for a 2D game, they should be instantaneous.

The UI has a weird bug where during questioning of a defendant you can’t fully scroll up the list of questions. Generally, the UI design is inconsistent and lacks indicators for navigation. More than once was I stuck in some menu for several minutes figuring out how to make the game do what I wanted it to.

Another thing regarding the UI: the text is really small, and there is no option for increasing the font size. To play this game on the Switch in handheld mode, I had to figure out how to use the Switch’s accessibility zoom feature.

Conclusion

I’m really let down. This should have been exactly my type of game, but its lack of focus and unnecessary technical quirks turn it into a test of patience instead of an exploration of the psychology of the leaders of a revolution during uncertain times. There are hints of a much better and good game present during chapter one, and it is a shame it can’t live up to any of that.

3/10

Gyakuten Kenji 2 a.k.a. Ace Attorney Investigations 2, is the Japanese-only sequel to Ace Attorney Investigations: Miles Edgeworth. The game’s plot immediately follows the events of the predecessor. Again, you take control of persecutor Miles Edgeworth to investigate and solve many different cases, together with his young assistant Kay Faraday and his subordinate policeman Dick Gumshoe. Previously having smashed an international smuggling ring, they are given no break and are immediately caught up in new cases to investigate. Their efforts slowly uncover a conspiracy that goes all the way up the prosecutorial chain of authority.

An impressive display of fan labour

First of all, this is an English review of a game that was only officially released in Japan. This is only possible, because of an amazing fan translation.

The quality of the translation is just astonishing. Beyond the translation of dialogue, it also overhauls images and 3D textures for the English language and features original voice acting work for new characters. It is faithful to previous official English translations. But the overall style isn’t forcefully imitated either. When it comes to introducing new characters with unique quirks, the transition is seamless.

This translation would be indistinguishable from previous translations for the Ace Attorney series if it wasn’t for the occasional fandom insider reference. After all, this is a translation made by fans for fans.

Seriously, if doubts about the quality of this fan translation are holding you back—please play this game! I promise, you will enjoy it.

I’ll take one (1) California roll, please! (Credit: Capcom. Fair use.)

Declaring war on unjust justice

This sequel greatly extends its predecessor’s themes of the incongruence between the law and genuine justice.

In this game, we will see Edgeworth consciously abandoning the von-Karma-way of justice. Previously he sought to prove the defendant guilty in court, no matter what it takes. But now, he is increasingly distrustful of the methods of his mentor. His trust in the justice system is broken in the same way.

Together, with his friends’ help, he takes an adversarial stance against the highest prosecutorial authority in the country, which leads him to temporarily abandon his role as prosecutor and join forces with a defence attorney. And later, the law is directly weaponised against Miles. He was enforcing it against others, up until that point, but never had it turn against himself.

With this, the game manages to spell something out clearly that predecessors ever only managed subtextually: the law is inadequate in delivering justice, and the corrupt institutions enforcing it fail people regularly and perpetuate the harm they are meant to prevent.

However, the most interesting message of these games, that the law’s ability to deliver justice, is merely a belief, remains subtextual. There are hints in this direction. For example, one of Edgeworth’s rival prosecutors is quite reminiscent of the inquisition (their theme is even played on a pipe organ). And for another, the meeting room of the national highest prosecutorial authority looks like a church with stained glass windows. Unfortunately, however, the exploration of this theme seems to take a secondary role to the one mentioned above.

Furthermore, the game explores the struggle of stepping out of the shadow of one’s father. We learn more about Miles’ father, a defence attorney, and his struggle over having ended up a prosecutor. Additionally, the game features another startup prosecutor, who, throughout the game, has to learn to go against his father, to become a proper man of his profession. The scene where this finally happens makes for a very satisfying conclusion.

Structure

The overall storytelling structure remains largely intact with some improvements, but this also means that flaws from the predecessor persist.

One thing that is also true for the previous game is that the very linear structure allows for very tight storytelling. Usually, a bit of time passes between each entry in the series, but the story continues immediately. This is one of the major distinguishing factors between these spin-offs and the main entries in the series. One of these styles isn’t better than the other. But for an investigation game, it is arguably a better fit.

Beyond that, the game improves upon its predecessor by spacing otherwise familiar characters from the series out through the game, instead of cramming them all into a singular case. The focus here is a lot more on characters that were previously seen in just one case. So it’s nice to see those familiar faces again and see where they stand now.

Chapter parts, unfortunately, continue to vary in length heavily. This makes it hard to plan for game sessions. It’s frustrating to start playing a part, expecting it to last an hour, and then having to spend double of that time to reach the next save screen.

A few gameplay additions

Gameplay-wise the game largely continues with the things set up in the predecessor. Nothing was removed, and some new things were added.

A new addition is “Logic Chess”, a timed interrogation, where you have to extract information from people by examining what they are saying and finding contradictions. Having a mechanic with time pressure is a first for the series. Initially, this feels alien for this type of game, but over time I found that it accentuated the urgency of some of the situations quite well. On top of that, it makes you think a lot more about what path you want to go through the dialogue tree, while always feeling the pressure of the clock ticking down. It makes for a nice and refreshing challenge.

Another addition is how recreated crime scene investigations with “Little Thief” have been extended to cover multiple periods in time that you can switch to at will. It requires that you build a bigger mental image of the crime scene instead of just looking at everything one by one. This, however, can also lead to confusion. One frustrating aspect of this addition is that the exact same dialogue triggered by the same object at different points in time are duplicated, and thus you can’t skip through dialogue that you have already read. It can be confusing to stumble across already encountered dialogue and be puzzled if the intuition of having seen this before is real or not.

Otherwise, things have stayed the same. This is mostly fine, but I remain disappointed by the “Logic” feature. Combining literally two facts about the case for more insight isn’t that interesting or challenging. Sometimes the connection between the two facts is spurious, and you have to guess more than actually deduce.

Conclusion

Overall this is an excellent game—probably the best in the series up until that point. The predecessor left me somewhat cold, but this game alone makes playing it totally worth it.

8/10

Metroid: Other M is the 2010 main entry into the long-running Metroid series that hadn’t seen a major release for almost a decade at that point with Metroid Fusion. The series at large had already seen a return to home consoles with the Metroid Prime spin-offs, but this game brought the main series back to them as well. With this return Team Ninja and Nintendo attempted to give this series a new coating: getting the main series to 3D, shifting the gameplay focus to combat, and extending the Metroid universe with a huge story.

Similarities/Differences

There is a lot of overlap with previous Metroid games in Other M, despite these huge ambitions.

Structurally the game borrows heavily from Metroid Fusion, taking place in a huge spaceship with one main sector that branches off into several others, each with a different theme. And also the story takes quite a bit out of Fusion’s book: it focuses on the Galactic Federation and its secret bioweapons research—just much bigger in scope this time.

The transition to 3D had already happened successfully for the series with the aforementioned Metroid Prime by Retro Studios. And certainly, a lot of lessons learned about how to transform the exploration of environments from 2D to 3D were applied here. But unlike Metroid Prime, Other M uses the third-person perspective, instead of first-person.

Story

The main difference between this game and the rest of the series is the storytelling. Up until this point the series had mostly relied on telling its story through the environment and events that are experienced directly in the gameplay space. This basic approach had already been extended by Fusion with a periodically delivered monologue, either directed at the protagonist, Samus Aran, or monologue of her own—directed inwards. Other M keeps all of this and erects a framework of a grand, traditionally told story around the entire game. Samus receives a backstory, explicit characterisation, and a cast of characters to interact with. On top of that, the game is fully voice acted. And all of this is supported by pre-rendered cutscenes by the animation studio D-Rocktes, which look spectacular, especially by Wii standards.

The game is set directly after the events of Super Metroid. Samus returns from her mission in that game, in which she successfully obliterated the planet of the Space Pirates. The baby Metroid that she set out to rescue on the mission, however, sacrificed itself in the final battle to rescue her.

Other M sets off when Samus receives a distress call which leads her to a seemingly abandoned and gigantic spaceship. And there she coincidentally bumps into a Galactic Federation squad under the leadership of her former military superior Adam Malkovich. She joins the group under Malkovich’s command and they begin investigating the place together. Soon it becomes clear that the ship houses the Galactic Federation’s secret bioweapons research project and that the place might house some other secrets too.

The story builds up Samus’ character and paints a pretty harrowing picture. The loss of the baby Metroid that saw her like a mother has affected her greatly and now, meeting people from her old life in the Galactic Federation army, opens up many wounds from the past. The game communicates her bad mental state by giving her a cold, detached and monotone voice, especially for internal monologues.

Throughout the game, you dive deeper into her damage with previous missions of hers and specifically her relationship to Adam, whom she sees as a father. This is also why she joins the group so readily under Adam’s command: she wants to make amends for the mistakes that lead to her leaving the military. She wants to prove her loyalty to him.

Broadly, the game has a theme of loss of control. Not only does Samus, who generally works alone, surrender authority to Adam, but further, many important plot points in the story do not get resolved by her. She isn’t the one in control, even though she is the protagonist of the game.

Moreover, by casting the Galactic Federation in the role of the villain, Samus doesn’t have much room to play the hero. After all, those are the people on whose behalf she just carried out her last mission.

The good-evil reversal with the Galactic Federation doesn’t sound all that interesting on the surface—that’s what Fusion already did—but combining it with Samus’ involvement and turning it into a story of overcoming trauma is a lot more compelling already. It goes further though: not only does nothing fundamentally change about the evil parts of the Galactic Federation, its bioweapons experiments continue in Metroid Fusion, which chronologically follows Other M. Adam Malkovich is portrayed as the only counterweight, as he explicitly opposed the bioweapons research but failed in preventing it from happening.

It’s a display of cynicism about the ability of large political constructs being able to rid themselves of their corrupt elements. The parallels with the public debate in Japan about raising a standing army once again, which is pursued by an ultra-nationalist elite, but majorly opposed by the general public, are striking. And beyond the contemporary political messaging, it also touches on the uneasy realities of being complicit in such an organisation, like Samus is. She continues to work with the GF, only to realise that nothing changed and finally breaks with them in Fusion. This allows her to finally step into Adam’s footsteps in defying the Federation.