Latest reviews

Founded in 2009 by Luis von Ahn of reCAPTCHA fame, Duolingo has quickly become the most popular free language learning tool, reaching some 150 million users today. Is it any good? The short answer: yes, but if you’re serious about learning a language, use it in combination with other resources.

After you sign up, the core experience is a set of interactive exercises focusing on different areas of a language: basic vocabulary, sentence structure, past and future verb tenses, and so on. Learning takes place along a sequential path, but you’re encouraged to repeatedly practice previous lessons.

Standard exercises include

-

practicing vocabulary using photographs (sort of like flash cards)

-

translating sentences in either direction

-

writing down what you hear

-

multiple choice quizzes of the “pick the correct translation(s)” variety

-

speaking sentences in the language you’re learning (the automatic validation errs on the side of marking your pronunciation correct)

This variety keeps the lessons interesting, though even after months of use, I still sometimes translate when I’m supposed to be transcribing. The mobile app minimizes the amount of typing by letting you “tap together” sentences rather than writing them, easing the difficulty a bit in favor of keeping things user-friendly.

One huge plus is that Duolingo is generally pretty good at accepting multiple translations for the same phrase. Sure, users still complain about correct translations not being accepted, but compared with language learning applications I’ve tried in the past, it handles the very large solution space pretty well, at least in Spanish.

Speaking of user comments, every exercise is linked to a discussion forum, which often contains helpful tips, both from other learners and native speakers.

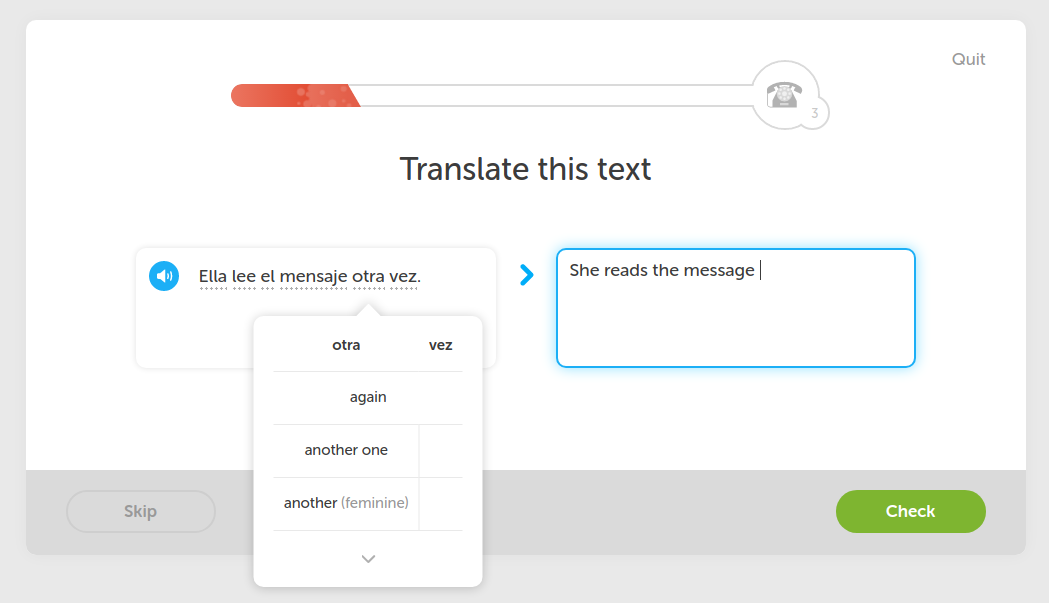

A typical Duolingo lesson will include translation exercises like this one. The UI is streamlined so you never really get stuck — you can always quickly refresh your memory through built-in hints.

Duolingo is well-funded and its product designers and engineers routinely launch new experimental features. For example, as of this writing, the “Labs” section features Duolingo Stories, which are interactive, spoken short stories where you complete sentences as you go. The iOS app, meanwhile, is currently experimenting with chatbots.

This is all well and good, but the core product isn’t receiving nearly as much love. Aside from the exercises, there’s very little context that helps you to learn about grammar or the internal patterns of the language you’re learning. Some lessons include some instructive text, which tends to be both minimal and not very well-written. And once you’re done with the lessons (which, for Spanish, took me a few months), you’re still at very limited proficiency with nothing else to do but to practice or to try more “Labs” projects.

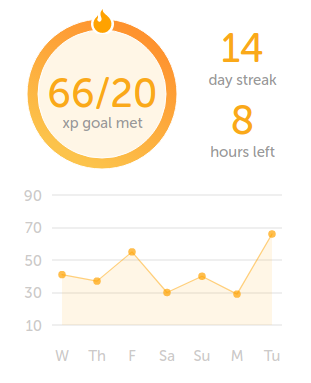

Gamification is a core part of the Duolingo user experience. The site tracks your daily usage, rewards you for completion of lessons, and sends you (genuinely helpful) reminders to keep at it.

On the positive side, the gamification — daily reminders, XP scores, levels, gemstones, etc. — does work to develop a language learning habit. Even aspects that may seem excessively silly (the mobile app lets you dress the Duolingo mascot in fancy clothes with the gemstones you’ve earned) do increase the user’s emotional investment in the learning process.

The business model is advertising (earlier plans to monetize translations notwithstanding), and the company has so far generally maintained a “not evil” reputation. You can even turn off the ads by paying a monthly fee, though most users will probably not find that to be worth it. With a high valuation and repeated injections of huge amounts of funding, let’s hope Duolingo continues to follow the straight and narrow.

I recommend Duolingo wholeheartedly — just don’t expect that it’ll be enough to get you from novice to pro. Use it in combination with books, videos, or free courses like Language Transfer. If you live in a big city, face-to-face Meetup groups can also be a great way to find other language learners and native speakers.

I remember well the chills I felt listening to Barack Obama’s victory speech from Grant Park in November 2008. As a recent immigrant to the United States, it seemed like I was witnessing an important new beginning for a country that had struggled with the legacy of slavery and segregation for so long.

Two years later, legal scholar Michelle Alexander published The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness, taking stock of America’s criminal justice system and issuing a warning against premature optimism in light of Obama’s victory. As the title suggests, Alexander’s book links America’s globally unique system of mass imprisonment with the decades of post-slavery segregation, discrimination and voter suppression known as the Jim Crow era (named after a racist blackface caricature).

The new racial caste system

Alexander’s thesis is that the system of segregation has simply been replaced by another racial caste system, one which is compatible with America’s newly found ethos of “colorblindness”. Through the “War on Drugs” and related “anti-crime” campaigns heavily targeting poor, black communities (without a plausible justification for this racial bias), the United States swept millions of African-Americans into the criminal justice system.

Massive sentencing disparities such as the whopping 100:1 weight ratio determining crack cocaine vs. cocaine sentences (reduced to 18:1 with the Fair Sentencing Act) kept them there for much longer. Upon release, they are stuck with felony records that are the basis for legalized discrimination ranging from voter disenfranchisement in some states, to housing and employment discrimination. They are a despised underclass which anyone can hate without repercussions.

Through one Supreme Court decision after another, apparent constitutional protections have been eroded at every step of the way — from racially biased policing to unfair sentencing and all-white juries. On page 119 (2012 paperback edition), Alexander notes poignantly:

It is difficult to imagine a system better designed to ensure that racial biases and stereotypes are given free rein—while at the same time appearing to be colorblind—than the one devised by the U.S. Supreme Court.

This system, which never exclusively targets African-Americans but is heavily biased against them, has been established by both Democrats and Republicans. Its foundation was laid by Ronald Reagan and his new “War on Drugs”, while mass incarceration itself was perfected by Bill Clinton’s “tough on crime” administration.

Michelle Alexander supports these observations with countless studies and statistics. Her writing is provocative but always grounded in the facts, and her conclusions are inescapably correct.

Importantly, Alexander notes that the “new Jim Crow” is not simply a “gentler” successor to the system of racial segregation that preceded it; it is in many ways more pernicious. Millions have been demonized and caged like animals. But because the system operates largely without open declarations of racist beliefs, it is difficult to challenge or even talk about without predictable “then just don’t commit crimes” responses (ignoring that white people go free for the same crimes that black people are punished for).

The system endures

Since Alexander’s book was published, no major criminal justice reform has been implemented, and America continues to lead the world incarceration rankings. Its prisons are known for human rights abuses, from shackling pregnant women (even during delivery) to forcing prisoners to endure extreme heat (and sometimes die from it). It practices solitary confinement for long periods under horrific conditions, and even forces prisoners to share cells designed for solitary use, leading to predictable results.

Barack Obama was succeeded by a far-right reactionary with open sympathies for white nationalists and other despicable groups. Indeed, Donald Trump ran a playbook “law and order” campaign frequently employing racist stereotypes, primarily targeting immigrants. After losing the popular vote by millions, he was swept into office by an electoral system that was designed to boost slave-owning states’ voting power based on how many slaves they owned.

The new Attorney General, Jeff Sessions, is keen to reboot the War on Drugs once more, and has already reinstated harsher sentences for low-level drug offenses. For-profit prisons, police militarization and civil forfeiture are en vogue again. Together, these measures ensure that mass incarceration will be with us for years to come. And by pardoning indisputably racist, vile and criminal Sheriff Joe Arpaio, Donald Trump himself has sent a clear message about his expectations from law enforcement.

An essential guide to an ugly reality

New developments notwithstanding, seven years after the first edition, Alexander’s book remains an essential guide to uncovering the reality of America’s new system of racial control. It is a difficult, painful read, but it opens our eyes to the scale and severity of this challenge.

Though written by a legal scholar, Alexander is critical of tunnel vision and the “NGO-ization” of liberation movements. Indeed, if you previously thought that the US Supreme Court is on the side of moral progress, this book will convince you that it all too frequently simply bolsters the prevailing systems of control. Though Alexander advocates no specific political philosophy, she endorses broad movement-based politics in the spirit of Martin Luther King Jr. (including his frequently forgotten Poor People’s Campaign).

Alexander’s scholarship has predictably been questioned by people invested in the status quo, but it is rock solid. When looking at attempted “rebuttals”, be sure you’ve actually read her entire book (she anticipates many responses), and that you’re familiar with the “stock and flow” distinction.

Also note that Alexander does not explore in-depth the connection between the drug war and violence; other scholars have demonstrated that drug-related violence is the inevitable byproduct of aggressive prohibition politics. Johann Hari’s Chasing the Scream about the drug war, while not as rigorous as Alexander’s work, is an easy read and very complementary (see my review).

Finally, while The New Jim Crow is well-sourced, it uses statistics primarily to underscore its key points; for extensive charts and data, see sites like the Sentencing Project, Vera, the Drug Policy Alliance, and the Brennan Center.

I took a class at my school. I learned how to take an idea in, think about it and decide how much truth it holds. Some people call this process “critical thinking” or “rational inquiry.” Call it what you will; all people should build this skill.

People across the world practice critical thinking. The people belong to a group called “the skeptic community.” Some members of the skeptic community stand tall with fame:

-

James Randi

-

Penn and Teller

-

Michael Shermer

-

Peter Bhoghossian.

I had to read a book for my critical-thinking class. I read Bullspotting by Loren Collins. Collins has worked in the skeptic community for years. He found his niche when he started to fight back against the Obama Birth conspiracy theory. But I had never heard of him. So, I started his book without bias.

I stopped believing in God in 2000. Since then, I took up critical-thinking as a hobby. I loved to learn about it. I loved to learn about who practiced it. But I never spent time learning how to practice it myself. At last, I learned when I read Collins’ book.

As I read, I learned about the dangers that come when bad ideas get popular. I learned about the hazards you risk when you take a false idea as true. Then, I learned how to stay safe from these risks. I learned how to see if an idea follows good logic. I learned how to see the symptoms of lies, bad science and empty claims. And, I learned about the different shapes and sizes that these threats come in. For instance, a rumor starts from one of three causes:

-

someone heard something wrong

-

someone understood something wrong

-

someone remembered something wrong

Also, a person will pull off a hoax (or scam) for one of three reasons:

-

for fun

-

for money

-

to get ahead in their own way.

Collins spends time telling stories of famous conspiracies and hoaxes from the past. He goes into detail about how they started, how they grew and how they ended. Then, he looks at the symptoms they held; he shows how they fooled us. At last, he shows us how we could have spotted the lies and saved ourselves from damage. Collins covers topics like:

-

Holocaust Denial

-

Moon Landing Denial

-

Alternative Medicine

-

9/11 Truth Conspiracies

-

Creationism

-

14th Amendment Citizenship in the USA.

When you read Bullspotting, you will get smarter. You will gain knowledge when you read it. And, you will get a weapon: you will get a skill that filters out nonsense as you take in new information. This will make you learn with more efficiency.

Bullspotting holds only two-hundred pages. But it goes by at a slow pace. It goes at this pace because its two-hundred pages hold a lot of information. I wanted to take it all in as I read. And I wanted to understand it. And keep it. So, I took my time to read it. And so should you.

I read Bullspotting; I feel smarter than ever. Also, I feel safer. I feel safer because I will never fall for a scam again. I will never make a bad decision. I will never get a treatment that science doesn’t say works. And, I thank Collins for that.You should read the book yourself.

You can get a copy here.

Hollywood blockbuster action movies are full of depictions of military machinery, of men and women in uniform, of undercover agents. These depictions are often the direct result of partnerships between the filmmakers and the Department of Defense, the CIA, or other government agencies.

In exchange for access to equipment and personnel, the government may provide remarkably detailed script notes ranging from legitimate factual corrections (“General Perry would likely not be the convening authority”) to changes in plot and characterization (“To make [the civilian ambassador] look like a real wet noodle, have [the Lieutenant] say …”). The viewer is none the wiser that the film they’ve just seen was originally more critical, or that important elements of the plot were changed.

Matthew Alford (Teaching Fellow for Propaganda Theory, University of Bath) and Tom Secker (writer, podcaster, researcher) are authors of a new book, National Security Cinema: The Shocking New Evidence of Government Control in Hollywood, which documents these connections. It is based in significant part on new research under the Freedom of Information Act.

To his credit, Secker has put the source documents online as a ZIP file. Whether or not you buy the book, I recommend grabbing a copy. Incidentally, the quotes above are from the Marine Corps script notes to Rules of Engagement, and they cannot currently be found anywhere else on the Internet.

Much of the book consists of case studies, contrasting the requested changes to movies like Iron Man, Lone Survivor, or Charlie Wilson’s War with the original script, or (where applicable) source material and actual events. It cites examples from film and television, and also briefly discusses financial incentives which may reinforce pro-military biases, such as product placement by gun manufacturers.

The book is poorly edited and includes both typos and repetitions that could easily have been caught. It would also be a stronger book without conspiratorial tangents about, e.g., the timeline of 9/11’s doomed Flight 93. Co-author Tom Secker is no stranger to conspiracy theories, which undermines the credibility of this work.

In spite of these distracting flaws, the authors have done important work in documenting the pervasive pro-government, pro-military biases in US entertainment. Read critically and patiently, National Security Cinema does offer a necessary and useful perspective on these biases, and the downloadable archive of source documents is an excellent starting point for anyone wanting to explore the topic further.

Further reading

Co-author Matthew Alford wrote a good introduction to the research featured in the book for The Conversation (a nonprofit media outlet which I’ve previously reviewed here): “Washington DC’s role behind the scenes in Hollywood goes deeper than you think”.

This is just to share my experience. (I am in no way affiliated with Technoethical.)

My background

I am a satisfied Debian user since I moved away from Windows in 2008. Back then I thought I could trick the market by ordering one of the very few systems that didn’t come pre-installed with proprietary software. Therefore I went for a rather cheap Acer Extensa 5220 that came with Linplus Linux. Unfortunately it didn’t even have a GUI and I was totally new to GNU/Linux. So the first thing I did was to install Debian because I value the concept of this community driven project. I never regretted it. But the laptop had the worst possible wireless card built in. It never really worked with free software.

In the mean time I have learned a lot and I started to help others to switch to free software. In my experience it is rather daunting to check new hardware for compatibility and even if you manage to avoid all possible issues you end up with a system that you can not fully trust because of the bios and the built in hardware (Intel ME for example).

The great laptop

Therefore I am very excited that you can actually order hardware nowadays that others have checked for best compatibility already. Since my old laptop got very unreliable recently I wanted to do better this time and I went for the Technoethical T400s, which comes pre-installed with Trisquel.

I am very pleased with the excellent customer care and the quality of the laptop itself. I was especially surprised how lightweight and slim this not so recent device is.

When the ThinkPad T400s was first released in 2009 it was reviewed as an excellent, well built but rather expensive system for about 2000 Euros. The weakest point was considered the mediocre screen. The Technoethical team put in a brand new screen which has perfectly neutral colours, very good contrast as well as good viewing angles. I’ve got 8 GB RAM (the maximum possible), an 128 GB SSD (instead of 64 GB) and the stronger dualcore SP9600 with 2.53 GHz (instead of the SP9400 with 2.40 GHz) CPU. In addition I’ve received a caddy adapter for replacing the CD/DVD drive with another hard disk. And all this for less than 900 Euros.

This is the most recent laptop of the very few devices worldwide that come with Libreboot and the FSF RYF label out of the box. The wireless does flawlessly work right away with totally free software. This system fulfills everything I need from a PC as a graphic designer. Image editing, desktop publishing, multimedia and even light 3D gaming. Needless to say that common office tasks as emailing and web browsing do of course work flawlessly. To get everything done properly only few people do actually need more powerful working machines.

The battery is a little weak

The only downside for power users on the go might be the limited battery life of about two hours with wireless enabled. It is possible to get a new battery which might extend the life to about 3 hours but because the battery is positioned on the bottom front you can’t use a bigger one. (The only sensible option would be a docking station, but I was never fond of those bulky things that crowd my working space even when the laptop isn’t on the desk.)

Summary

Over all this is a great device that just works with entirely free software. I thank the Technoethical team for offering this fantastic service and I encourage you to support ethically motivated companies like Thechnoethical instead of getting your hardware bundled with proprietary software because without investing money in technology we want we will never get to the point where it is easy and normal to chose free systems right from the start without the need for additional work to liberate yourself by becoming a person that is technically more skilled than average users are.

I can only recommend buying one of those T400s laptops from Technoethical.

When the Wachowskis and J. Michael Straczynski collaborate, you know you’re in for a treat to the senses. The basic premise of Sense8 is wild: humans are evolving the capacity to form small “clusters” that share memories, experiences and skills across vast distances, telepathically dropping in on each other’s lives, walking in each other’s shoes.

That premise is used to challenge the viewer to embrace diversity in all its forms, while telling the story of one such cluster and its fight against the inevitable attempt to halt or hide the evolution of the “sensates”.

Meanwhile, the members of the cluster also have to deal with prejudice and drama in their own lives. Trans woman Nomi Marks faces rejection and abusive comments by her bitter, hateful mother; actor Lito Rodriguez has to face coming out as gay in Mexico; bus driver Capheus Onyango deals with organized crime and corruption in Kenya’s Kibera slum.

The show is unflinching in its portrayal of life’s richness and diversity. Recreational drug use, group sex, polyandry, gay and lesbian relationships, and much more all on proud, prominent display. Its in large part the show’s willingness to explore the emotional depths of these experiences that makes it such a remarkable piece of entertainment, owing perhaps to the creative freedom afforded by working on a Netflix production.

Gratuitous? Not really — the core theme of the show is empathy (as symbolized through the psychic connection between the “sensates”), so it makes sense that it would use its large canvas to paint a world where prejudices can and must be overcome. If anything, the show barely touches on themes like disability, mental illness, religion, or many other characteristics that are used to divide and stigmatize.

The only real problem with Sense8 is its plot. The actions of the “cluster” are often difficult to follow, owing to quick jumps and the confusing mechanics of how “sensates” communicate with each other. The bad guys are simplistic and their motivations shallow. As in most TV shows, hacking is portrayed as some kind of magical superpower that lets you take over any computer system within 5 seconds. Some scenes, such as a confrontation during a wedding ceremony in the second season, are cringe-inducing due to ridiculous dialogue and plot.

These are forgivable problems, and the show is still a lot of fun in spite of them. It has gained a significant online following, and while we’re unlikely to see more than the two seasons that have been produced so far, Netflix has at least committed to producing a finale (the last episode ends on a “to be continued” moment).

It’s a unique show in many respects and has many beautiful, glorious moments. Filmed in locations including Berlin, Chicago, London, Mexico City, Mumbai, Nairobi, Reykjavík, San Francisco, and Seoul, it is vibrant with energy and life. Watch it, just prepare to be confused or to cringe now and then, and not because of the lovely, diverse cast or the group sex. :)

First published by Yale University Press in 1998, James C. Scott’s Seeing Like a State is one of those rare scholarly works that have achieved wide intellectual impact beyond academia. Its core thesis is simple: states and large corporations depend on radical simplification to plan and execute, and in the process, they often ignore the skill and wisdom of the people whose lives they seek to direct. When this faith in rationality is combined with the power to coerce, disaster and misery may follow.

The case studies in the book range from collectivization in the Soviet Union to the planning of large cities. Agriculture is one of the domains Scott is most familiar with. Consequently, much of the book elucidates just how much skill and knowledge are employed on family farms and by pastoralists, even if that skill was acquired more by a “stochastic” method (trial and error) rather than a scientific one. This makes apparent the tragedy of collectivization, which devalued the skill of farmers in order to better control their productive output (or more specifically, that part of their work the state was interested in).

The book’s biggest strength are these insightful case studies; its weakness is its plodding repetition of the same argument over and over again, along with some unnecessary jargon. With better editing, the book could have easily been brought down to 300-350 pages. This makes the book a bit of a slog, but does not distract from its importance.

To be clear, the author is not merely cheerleading for free markets. Indeed, he clarifies repeatedly that powerful market actors (especially when they conspire with the state) may implement similarly disastrous schemes to maximize their own profits. He speaks of the “ecumenical” nature of a faith in high modernism and documents how some “priests” of this belief system have been willing to enter the services of communists and capitalists alike, so long as they were permitted to pursue their ultimately destructive schemes.

Socialists who have faith in nationalization and other large government schemes should read the book to better understand the risks inherent in such projects; libertarian socialists may find it useful to support their skepticism of centralized power.

The book does, of course, not account for recent developments in computing that make management of large amounts of data (e.g., soil and weather data in agriculture) more feasible, nor does it help to navigate the transition to an information economy. These 21st-century developments should not tempt us to renew our faith in rationalist central planning but strengthen our commitment to building decentralized, resilient, cooperative networks.

Not recommendable for introductory reading, but quite a nice bedside table book for the experienced Python programmer. The entire book is made up of short to medium-length examples constructed by experienced Python programmers solving small real-world programming tasks together with a concise description. Great to learn the hidden intricacies of the programming language.

Charles Darwin referred to his landmark work, The Origin of Species, as “one long argument”, a title Ernst W. Mayr (one of the 20th century’s leading evolutionary biologists) adopted for this treatise on the “genesis of modern evolutionary thought”. First published in 1991, it remains useful reading to better understand how Darwin’s ideas were received and modified over time.

The most valuable insight I gained from the book is that speaking of “Darwin’s theory” is misleading, as Darwin was a proponent of many important separate scientific ideas, including:

-

evolution itself: life is not static, but constantly changing;

-

common descent: all life on Earth shares a common ancestor;

-

multiplication of species, e.g., through geographic isolation;

-

gradualism: evolution is a slow process, not sudden emergence of new types;

-

natural selection: thanks to genetic variation, from a given pool of individuals, some will have a higher likelihood of survival than others, and those characteristics may spread;

-

sexual selection: some characteristics may spread purely because they increase the likelihood that an organism can attract a suitable mate.

All these ideas were present in Darwin’s work, along with some others which were later refuted (such as Darwin’s continued belief in some aspects of Lamarckism). But what’s remarkable is how long it took for the full force of Darwin’s insights to become recognized.

At first, “Darwinism” was mainly identified with evolutionary thinking as such, and with the rejection of religiously motivated reasoning to explain life on Earth. Yet aspects we now recognize as fundamental, such as natural selection, were largely ignored. It would take many decades — and the work by other scientists such as August Weissman and Alfred Wallace — for evolutionary thinking to truly take shape. Understanding this history helps explain why Darwin remains so highly revered in the scientific community: on many of the key questions, he was right on target from the beginning.

This is a dry book, and at times (such as when Mayr tries to establish exactly how much influence Thomas Malthus had on Darwin’s thinking), the author’s attempt to develop a microscopic analysis of the history of Darwin’s thought processes seems almost quixotic. Nonetheless, that same methodological rigor is what gives the book its explanatory power.

For the most part, the book is understandable to a layperson; the final chapter (which deals with frontiers in evolutionary biology at the time) is both the most technical and the most noticeably dated. A glossary explains some of the commonly used scientific terms.

Recommended if you want to better understand how we naked apes came into the possession of the knowledge of how we came to be.

xkcd (reviews) is a lovely, nerdy webcomic and occasional canvas for larger scale experiments such as "Click and drag" or "Time". It’s also full of subtle references, inside jokes relying on technical or scientific domain knowledge, and easter eggs. explain xkcd, with the not-so-subtle tag line “It’s 'cause you’re dumb”, is a wiki that provides background, transcripts, and trivia on each episode.

And it doesn’t really matter how obvious the joke is — explain xkcd will still spell it out, like so:

Despite the skyline being clearly recognizable as St. Louis due to the Gateway Arch, Black Hat calls it New York City. However, the nickname he gives is neither a common New York nickname (such as “The Big Apple”) nor a St. Louis nickname. Megan tries to correct him, but it becomes clear that Black Hat is making up nicknames. Many of his suggestions are puns for real nicknames of other places.

But then look a bit further, and the same page contains a long table of all the various nicknames referenced in the comic, making the whole page a rather delightful expansion on the content of the strip.

And so it goes for almost every episode. It’s a beautiful idea, well-executed, and it’s being expanded into explain penny arcade, for the eponymous gaming focused web comic which also contains many references which may not always be obvious.