Reviews by Team: Nonprofit Media

We look for quality sources of news and analysis in the public interest

What is integrity? We expect governments to act in the public interest, to root out corruption, to uphold the rule of law. We expect businesses to follow the law, to pay their fair share of taxes, to not abuse their power. We expect nonprofits to act in accordance with their mission, to avoid wastefulness, to be transparent.

The Center for Public Integrity (CPI) is an investigative journalism nonprofit based in Washington, D.C. that’s dedicated to documenting abuses of power in these and other institutions. It defines itself as nonpartisan and has indeed conducted many investigations across the political spectrum.

Although its name and location might suggest a “think tank” type organization, CPI is fully focused on producing journalism – often published in partnership with other news outlets.

Funding and Executive Compensation

Founded in 1989, CPI had revenue of about $9M in 2015. According to its Annual Report, almost all of its revenue comes from grants and donations. Most of its support comes from large gifts and grants (many from the typical foundations that fund journalistic work); in 2016, CPI received $210K in donations smaller than $250.

As of November 2016, CPI’s CEO is John Dunbar, an investigative journalist and CPI veteran. Because of the recency of his appointment, compensation information is not available yet; his predecessor received $301K from the Center in 2015, which is squarely in the middle between ProPublica and the Center for Investigative Reporting in terms of executive compensation.

CPI states: “We maintain a strict firewall between funding and our editorial content.” It publishes its editorial standards which include a requirement for full disclosure of conflicts of interest, and a commitment to avoid such conflicts where possible.

Reporting

Compared with ProPublica and CIR, CPI has a stronger focus on institutions, both public and private. With regard to government, since 2001, no news organization other than the New York Times has filed more Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) lawsuits than CPI, according to a report by the FOIA project. These types of lawsuits are necessary to challenge government over-classification of materials.

The recent CPI report regarding what amounts to a massive gift to the insurance industry by the taxpayer-funded Medicare program is an example of an investigation that was made possible through a FOIA lawsuit.

CPI investigates both Republicans and Democrats, and I was not able to detect a bias towards either group. The report on ambassador postings for donors to the Obama campaign is a good example of data-driven journalism targeting the Obama administration, while CPI also reported in detail on the perks and access offered to big donors to Donald Trump’s inauguration.

Businesses are far from immune from CPI’s investigations. In 2014, CPI received a Pulitzer prize for an investigation which revealed “how doctors and lawyers working at the behest of the coal industry helped defeat benefit claims of coal miners who were sick and dying of black lung disease.”

After the 2008 financial crisis, CPI published some of the most in-depth reporting on the links between banks that received bailout money and the subprime lenders that caused the crisis. Through the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, which it launched in 1997 and which it houses, CPI has helped bring about the most important investigations into tax havens and offshore banking in recent history, including the Panama Papers investigation.

CPI publishes a running log of all corrections.

Website, Licensing

CPI’s website is easy to read and offers section views for its primary ongoing investigative domains (e.g., politics, business, environment). The content is not sensationalized, and as with other investigative sites, you’re probably more likely to read an investigation of interest to you through a social media or RSS feed than by going directly to the site. Content is generally in text form, and the site looks reasonable on mobile devices.

Donation appeals are visible but not annoying. Stories use Facebook comments as a discussion system; commenting guidelines are buried in the terms of use, and I did not see evidence of moderation (which doesn’t mean it doesn’t happen). Content is under conventional copyright and sometimes cross-published to other news media. In general, CPI is a cathedral-style journalistic organization with limited community engagement.

The Verdict

I would recommend CPI without reservations for your RSS or social media feed. The institutional focus distinguishes it from ProPublica and CIR, and this focus has led it to dig into some of the largest scale, most systemic abuses in areas such as the financial services industry. Its incubation of the International Committee for Investigative Journalists was a brilliant move in that regard, since many of the most complex tax avoidance schemes are international in nature. This makes CPI/ICIJ truly indispensable.

It’s not surprising that an organization with “Integrity” in the name does a good job with organizational transparency. Financial documents and annual reports are easy to find, and the donor information is comprehensive. In spite of all these editorial and operational strengths, CPI still has a relatively small online presence – 74K followers on Twitter, 83K on Facebook.

Doing more to engage (and involve!) readers through these channels without compromising on its strengths may help build a larger audience, which in turn may translate to more bottom-up funding. Given that CPI, ProPublica and CIR are all nonpartisan, we might also hope for more collaboration between them in future.

Because of its high impact business and government investigations, I give CPI 4.5 out of 5 stars, rounded up. It is now also in the Twitter list of quality nonprofit media.

In 1977, long before the Internet gave new life to nonprofit media, Bay Area journalists David Weir, Dan Noyes, and Lowell Bergman founded the Center for Investigative Reporting (CIR) in Oakland, CA. The nonprofit organization’s mission is to create investigative journalism that “sparks action, improve lives and protects our democracy”.

It did so initially by working primarily with other news outlets. A first major collaboration was a 1978 exposé by Kate Coleman and Paul Avery regarding the Black Panther Party and its involvement in organized crime, including murder. Since then, CIR has produced deep investigations about all sectors of society, for example:

-

“Reasonable Doubt” (with CNN), a 2007 investigation into poor quality controls at forensic crime labs

-

“Dirty Business”, a 2009 documentary about the myth of clean coal

-

“The God Loophole”, a 2016 investigation of abuse at religious daycare facilities

CIR has received numerous journalism awards, including a Peabody, and the organization was a finalist for a Pulitzer prize in 2012 for its investigation of earthquake safety of California schools.

This focus on wrongdoing in any part of society makes it similar to the younger, NYC-based ProPublica, and indeed, in many ways, CIR is its West Coast counterpart. The two organizations had nearly the exact same amount of revenue in 2014 ($10,324,242 vs. $10,324,275) and draw funding from similar sources, primarily foundations and major gifts.

Unlike ProPublica, CIR does not provide a breakdown of its revenue by source, but it does provide a list of supporters, which includes Gates, Carnegie, Rockefeller, Open Society Foundations, Hewlett, MacArthur, Knight, and many of the other big names in philanthropy. An editorial independence policy is meant to make it clear that such support does not influence reporting.

One notable difference between the two is executive compensation. CIR pays its Executive Director a total of $232K, while ProPublica’s highest compensated “co-executive” makes $429K. CIR does not publish an Annual Report, but it does use an open source impact measuring tool to produce whitepapers documenting the real world effects of some of its most notable investigations.

As an older organization, CIR had to transform itself for the Internet. It now publishes its investigations on Reveal, which features in-depth reporting, podcast episodes, videos, and occasional data journalism. The grouping of investigations (e.g., “Hidden abuses under the watchtower” for its Jehovah’s Witnesses investigation) makes the current focus areas reasonably clear.

While it utilizes text, audio and video for its reporting, in many other respects, Reveal is very old school. There is no commenting system, content is under conventional copyright (as opposed to a Creative Commons License), and the heading “Get involved” only leads to an ask for donations.

The Verdict

As with ProPublica, the universal search for abuse (and the heavy reliance on conventional funding) can make it harder to address system-level issues such as inequality, climate change, electoral injustice, or mass incarceration. Efforts like CIR’s are therefore no substitute for values-driven journalism that provides consistent emphasis on systemic injustice.

On the other hand, the Center’s investigations into all sectors of society do help people to learn about (and act on) abuse and wrongdoing within their communities. On that basis, I recommend following Reveal, and the feed is now part of the Twitter list of quality nonprofit media. 4 out of 5 stars.

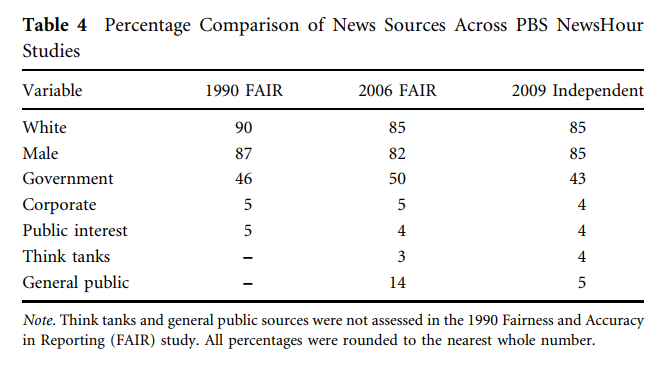

Journalists like David Brooks and Mark Shields provide background on the news, reflecting a general bias of sourcing (85% male, 85% white) that has been consistently documented.

NewsHour is the flagship public television news program in the United States, distributed by PBS and produced as a collaboration between key member stations. As with all public broadcasting in the US, it relies on a mix of funding that includes government support, corporate underwriting, foundations, major donors, and small donors. PBS programs are subject to funding standards, and an ombudsman serves as a verbose internal critic.

Executive compensation at some member stations reaches excessive levels by nonprofit standards – nearly $600K for WNET CEO Neal Shapiro (WNET co-produces NewsHour). This is a reflection of competition for talent with for-profit media (Shapiro was previously the President of NBC) and the large organizational size, but still merits scrutiny as it can reinforce leadership trading within a media oligopoly as opposed to the development of a unique nonprofit media leadership path.

NewsHour made its debut as a nightly news program in 1983. It features headlines, interviews, and some in-depth reporting. Episodes can be streamed online, and segments of the program are routinely transcribed. Probably the biggest difference with for-profit news programs is tone, not content. The program projects a sense of respectful, calm, civil engagement with the issues of the day. That’s no small thing in an era where networks like CNN employ extreme partisans just to shout at each other. Of course, it can also contribute to normalization of extremes.

As far as content is concerned, NewsHour does generally take a longer, more global view than many other news programs. It routinely features topics from US history, developments in other cultures, and so on. The commitment to balance that’s part of the public broadcasting mandate typically translates to having a center-left and a center-right guest on the show for purposes of analysis (such as the Brooks and Corn / Shields and Brooks programs).

Studies both by progressive media criticism organization FAIR and by independent researchers have consistently shown that the sources NewsHour consults for expertise and interviews are 85% male, 85% white (the US is about 72% white), and about 45% government. Public interest sources, think tanks, and corporate sources are each sourced about 4-5% of the time.

That means organizations that are deeply familiar with topics like the drug war, voter suppression, the arms trade, etc., are rarely put on the air to talk about them. In its selection of core stories of the day, NewsHour also largely mirrors the choices of other news programs. There are exceptions, such its recent in-depth feature on the under-reported United States prison strikes, which is also notable in being singular.

The program exists in the larger context of public broadcasting in the US, which is frequently the target of efforts to either politicize or defund it. While government funding has its perils, the reliance on major donors and corporate underwriters also comes at a cost. Most significantly, Jane Meyer of the New Yorker exposed in 2013 how PBS member stations got cold feet about programs putting the spotlight on a major donor and trustee, David Koch of the infamous Koch Brothers.

Given this combined political and corporate influence, a program like NewsHour is likely to stay firmly within the Overton window in its reporting: views that are “too radical” either on the left or on the right will rarely be aired. But of course the window isn’t fixed – it remains to be seen how NewsHour will deal with the normalization of hate, and with politics under President Donald Trump.

The Verdict

For the time being, I still recommend NewsHour with reservations, since it at least leans towards public interest reporting rather than pure ratings-driven entertainment. It is a good bellwether of elite opinion, and provides more nuanced and careful analysis than any other centrist US news program I’ve seen.

3.5 out of 5 stars, rounded up. If you follow our Twitter list of quality nonprofit media, you will get updates from NewsHour alongside more political and adversarial sources like Mother Jones, The Intercept, and Democracy Now!, as well as the academic perspectives from The Conversation.

“The world deserves access to its greatest minds”, the slideshow begins, showing images of war zones. “Now more than ever the world needs access to reliable information.” The video is a fundraising ad for Project Syndicate, a nonprofit based in the Czech Republic.

The location reflects the organization’s original purpose. Project Syndicate was started in 1995 to help syndicate the views from “leaders and thinkers” from Western and Western-aligned countries to Eastern European newspapers. Today, it explains its model as follows:

News organizations in developed countries provide financial contributions for the rights to Project Syndicate commentaries, which enables us to offer these rights for free, or at subsidized rates, to newspapers and other media in the developing world.

While its tax returns are not publicly viewable, Project Syndicate’s CEO assured me that “it is registered as a public benefit corporation, 501c3 equivalent, in the Czech Republic. As such we register audited financials, board minutes, annual reports, etc every year with the appropriate Czech courts as required by Czech law.” He broke down the revenue composition of the organization as 60% subscriptions, 37% foundations, and 3% donations.

The website lists the Gates Foundation, the European Climate Foundation, and the UAE-based Al Maktoum Foundation as funders. That list is incomplete and may only reflect recent funding; George Soros’ Open Society Foundations, for example, gave $350,000 in 2014.

PS columns are translated by PS into multiple languages, and into many more by the participating newspapers. Each column includes a small speaker bio, but not a disclosure statement like the ones found in The Conversation (which I reviewed here).

Indeed, even funders themselves use PS to get their views out to newspapers around the world. This includes many columns by George Soros and by Bill Gates, two by Melinda Gates, and four by Mohammed bin Rashid al Maktoum. Each story includes an author bio, but does not disclose these funding connections.

Beyond its funders, the “greatest minds” whose opinions Project Syndicate spreads around the world include former and current world leaders, experts in academia, Nobel Prize Winners, and for whatever reason, Bjørn Lomborg. Lomborg, whose Ph.D. is in political science, has turned being a contrarian on environmental issues into a career, and his policy work (which many experts have described as scientifically dishonest) tends to be used by conservatives to justify luke-warmism: watered down approaches to solving environmental issues.

Columnists from politics include former UK Prime Ministers Gordon Brown and Tony Blair, former UN Secretary General Kofi Annan, former German foreign minister Joschka Fischer, and former US national security advisor Zbigniew Brzezinski.

Some of these folks are life-long public servants, others (like Blair and Fischer) have turned their post-politics careers towards more lucrative objectives. Blair in particular has been busy: consulting for the financial services industry, advising dictators through Tony Blair Associates, making a secret deal with a South Korean oil firm. None of these connections are disclosed in his PS bio, which focuses solely on Blair’s work through NGOs and academia:

Tony Blair was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1997 to 2007. Since leaving office, he has founded the Africa Governance Initiative, the Tony Blair Faith Foundation, and the Faith and Globalization Initiative.

This shows why disclosure statements are important.

By uncritically publishing views by Blair, Gates, Fischer, Brzezinski and other members of political and economic elites, PS implicitly will be less likely to air voices that are highly critical of them. This is not a publication that will give much credence to voices that allege that Henry Kissinger was a war criminal, a claim that even center-left Vox had to agree with.

Nor is it likely to criticize Brzezinski’s own record promoting Operation Cyclone, the massive, multi billion dollar program to arm Islamic extremists in Afghanistan as fighters against the Soviet Union, a program now widely regarded as exemplifying the blowback phenomenon where former allies turn against the state actor sponsoring them.

Indeed, as I write this, Project Syndicate is busy defending Saudi Arabia’s war in Yemen, with an editorial by Ali Al Shihabi, the “executive director of the Arabia Foundation, a new think tank that will focus on the geopolitics of the Arabian Peninsula”. Al Shihabi has calmly reassuring words for those disturbed by attacks such as the bombing of a funeral ceremony which led to 140 deaths. Totaling up the human cost of the war so far, he concludes: “For an air campaign waged for nearly two years against an unconventional army, this figure is not particularly high.”

That is not to say that Project Syndicate is a right-wing site. Far from it, its columns tend to occupy the center-left to center-right, to borrow a phrase from Hillary Clinton, and that’s following a more international definition of “centrism” than the right-leaning US version.

For example, PS created a special focus section on Donald Trump called “Trump: An American Horror Story”, and the site frequently reports on environmental issues and the international efforts to combat climate change. Here, too, it tends to follow more of a Hillary Clinton vision than a Bernie Sanders one, promoting fracking through several stories including, of course, one by Lomborg, who predictably calls it “this decade’s best green-energy option”.

In fairness, the credentialist centrism that defines Project Syndicate does leave room for a lot of sensible voices, including leaders of various NGOs and generally reasonable politicians arguing for peace, democracy, and apple pie. It has even given plenty of space to prolific progressive firebrand Yanis Varoufakis. But Jeffrey Sachs, who’s stuck with the project the longest as its first monthly columnist, is perhaps the best example of this benevolent form of punditry, the elite-friendly “how about we try this crazy thing” mentality that actually sometimes leads to positive agendas being implemented.

Project Syndicate content is licensed under conventional copyright – the newspaper subscriber model depends on at least some subscribers paying for the content. That said, the content is available online, sometimes in abbreviated form that requires logging in. There’s a small discussion section below each story, which usually receives a small to moderate amount of activity. There is no prominently noted way to submit corrections for any story.

The Verdict

Although non-profit, Project Syndicate is effectively mainly funded by for-profit media. It amplifies the perspective of elite voices across all sectors of society, while concealing conflicts of interest. The lack of obvious disclosure even regarding writers whose organizations are funders of the project, and the use of PR blurbs like Tony Blair’s, is especially iffy.

The bias towards credentialism is likely good for continuing to attract foundation funding and subscribers, but it doesn’t in fact engender a diverse set of perspectives. The Conversation, previously reviewed here, is a more inclusive alternative, in spite of its own selective focus on voices within academia.

Until Project Syndicate addresses some of its transparency deficits and manages to pivot towards a broader definition of “the greatest minds” with less emphasis on credentialism and increased focus on marginalized and underrepresented voices, I cannot recommend it as a source of analysis.

Nevertheless, I personally do follow Project Syndicate on Twitter to get a window into what views are being promoted by elites around the world, but it’s especially important to read it critically and conduct one’s own investigations of an author’s motivations and opposing viewpoints. Three out of five stars.

The Conversation may well be the most remarkable news site you’ve never heard of. After a start in Australia in 2010, the site has since added five editions: UK, the US, Africa, France, and a Global edition. The premise is simple enough: academics, researchers, and PhD students write news backgrounders, special reports, and explainers for complex topics, targeting a general audience. Readers are encouraged to engage in discussion with clearly stated and enforced community standards – and authors frequently participate in those conversations, as well.

The whole operation is fully non-profit, with funding that comes primarily from a large array of foundations and participating academic institutions. The most recent available tax return for the US edition, which is only 2 years old, notes about $2.3M in annual revenue, but The Conversation Media Group in Australia from which it spun off is a separate entity.

With a network of more than 36,000 writers, the scale of this project is staggering. These authors write in partnership with professional journalists who are part of the Conversation team. All content is under the Creative Commons Attribution/No-Derivatives License, which allows free republication without modifications, including commercial re-use. Because many sites do pick up their content, The Conversation’s reach extends well beyond the 3.7 million monthly users that go to the site directly.

The website runs on a custom content management system which is proprietary and likely to remain so. It is is quite well-designed: pages load fast, the multi-column layout is easy on the eye, the navigation makes sense, and it’s mobile-friendly. The commenting system is one of their own creation which, as of this writing, lacks functionality to edit one’s own comments but is otherwise easy to use.

Each edition has its own Twitter/Facebook/RSS feeds, so in order to get a mix of global and US posts, for example, you can just subscribe to both feeds.

So, what’s the content like? If you’re familiar with Vox.com, think of The Conversation as a less sensationalist version that is more careful with the facts while serving up more diverse views from around the world. Alongside lots of mundane stuff (the US frontpage article right now is “How making fun weekend plans can actually ruin your weekend”), that includes radical perspectives from time to time when they can be found in academia, such as articles by Greek academic and progressive firebrand Yanis Varoufakis.

And it also includes charming articles like How majority voting betrayed voters again in 2016, where a French mathematician advocates that the US should immediately adopt a voting method for presidential elections called “majority judgment” he and a colleague have devised. (The argument is interesting enough, but without grounding in any kind of political reality it is indeed a purely academic one.)

Consistent with standards in academic publishing, authors must disclose conflicts of interest and “relevant affiliations”, making it harder for the site to act as a conduit for advocacy by special interests.

All articles I’ve read meet a certain minimum bar of quality (they make an effort to engage the reader, they’re accurate and clear), but the ceiling varies considerably. In quite a few cases, you’d be better off heading over to Wikipedia to understand a subject, not because the backgrounder by The Conversation is wrong, but because it just consists of a few links and some fairly banal observations. Still, the site is (in my view) vastly preferable to commercial offerings like Vox because it publishes a truly diverse and increasingly global community of authors.

The Verdict

The Conversation is unique, and the site’s founders deserve credit for realizing a bold vision of a non-profit platform that helps us engage in smarter conversations with each other about the world we live in. Whatever your political views, I suggest adding one or more of their feeds to your news mix to sample their content.

If I could pick one area for the site to improve in, it would be to focus more on truly excellent journalism at the expense of sheer volume. Beyond that, a stronger commitment to open source values (opening up the platform, engaging the community in governance issues, using a more permissive license for the content) would be lovely to see. 4 out of 5 stars.

Não é preciso ser especialista em comunicação para atestar o óbvio: a grande mídia no Brasil é controlada por poucas famílias, milionárias e com um interesse premente na manutenção do status quo. Muito do que se chama de “opinião pública” nada mais é que o eco dos mesmos jornalistas, sempre com a mesma agenda liberalizante e sob um cínico véu de imparcialidade. É nesse contexto que pequenas publicações como o Outras Palavras se fazem necessários.

O Outras Palavras é uma plataforma com uma perspectiva de esquerda, e conta com uma riquíssima gama de temas, da economia às artes e da política à tecnologia. Nenhuma temática é imune de problematização, e isso inclui a própria esquerda, que é frequentemente autocriticada.

O site, que ostenta uma licença Creative Commons BY-SA, republica textos de outros autores, traduz peças de pensadores contemporâneos e cria conteúdo original, numa mistura bastante abrangente e interessante. É um dos poucos veículos de esquerda que não insistem no governismo tosco típico da Carta Capital, por exemplo, ou que sentem nostalgia por experimentos socialistas fracassados, como o vermelho.org.br.

Quanto à sua independência financeira, cabe aqui ressaltar uma informação importante sobre como o portal é financiado:

Em 2015, os leitores contribuíram com R$ 140 mil – o que correspondeu a 71% de nossas despesas. Em 2016, planejamos gastar R$ 238,8 mil […]. Deste total, R$ 210 mil – ou 87,5% – virão de contribuições solidárias, por meio de Outros Quinhentos.

Recomendo a todos que desejam estar a par dos acontecimentos recentes do mundo, sempre com um olhar afiado e crítico.

In 2008, journalist and author Bill Bishop co-authored The Big Sort: Why the Clustering of Like-Minded America is Tearing Us Apart. It examines how communities across the US are becoming more politically one-sided. This isn’t just a Kentucky vs. California thing – within these states, you’ll find increasingly sharp political divisions. Part of the reason is that people like to live with others who think like them: they “sort” into communities that reflect their values.

In this climate of polarization, it can become easy to fall into stereotypes, and to lose sight of common concerns that all communities share: jobs, access to health care, working infrastructure, clean water and clean air, and so on. Bishop is also a journalist and the co-founding editor (with his wife) of the Daily Yonder, a website that focuses specifically on the needs of rural communities. As such, it also seeks to overcome stereotypes and help people see the diversity of rural America.

The Daily Yonder is published by the Center for Rural Strategies, a non-profit based in Whitesburg, Kentucky, and Knoxville, Tennessee. The Center had about $832K in revenue in 2014, much of it from well-established foundations like the W.K. Kellogg Foundation (yes, named for the guy who founded the cereal company) and the Nathan Cummings Foundation. Although there’s a big fundraising button on every page, individual or small organization contributions average to only about $20K a year.

Its reach can only be described as tiny at this point: The publication has about 3,500 followers on Twitter and another 3,500 on Facebook (the Facebook page is more regularly updated); its traffic rank is similarly underwhelming. There are some self-inflicted reasons for this: once you get past the frontpage, it’s easy to get lost in the laundry list of topics and inscrutable headlines without any kind of content preview. If clickbait is one extreme of how to present news and analysis, the Yonder is close to the other end.

This also shows a fundamental challenge covering “rural America” as a whole: it’s big, and it’s hard to make local stories exciting for people who aren’t from that specific part of the country. Right now, the frontpage tells me in large letters: “DYNAMIC DELTA LEADERS: EDUCATION IS THE KEY”. Is that a story I want to read? Who knows!

But if you dig, there is lots of good content here. The Viewfinder series, for example, showcases rural photography. The In the Black series is a column that relates the experiences of an underground coal miner. Beyond Coal examines the transition from fossil fuel to renewable energy. The “Speak your piece” columns reflect on many aspects of rural life while staying clear of the vitriol that has become a mainstay of US politics.

Bill Bishop himself followed up on his “The Big Sort” analysis with an insightful article that examines the rapidly increasing percentage of voters who live in “landslide counties” where one of the two parties is likely to win a presidential election with large margins.

Each story has a small Disqus-enabled section for comments, though few stories attract significant discussion. The content is under conventional copyright, and some is syndicated from other sources.

The Verdict

The Daily Yonder deserves to exist, because it provides a much-needed journalistic perspective on rural America. But to truly reach people (rural or not), it will need to strive to become a more engaging source that can successfully perform the difficult task of translating local experiences into public interest journalism with broad appeal to readers in different parts of the country. Because it falls short of that potential, I give it 3 out of 5 stars. If you are interested in authentic perspectives on rural America, I do nevertheless recommend liking their Facebook page or subscribing to their RSS feeds as a way to keep up with their important work.

Jacobin is a New York based socialist quarterly magazine founded by Bhaskar Sunkara when he was 21 years old. It was started online in 2010 and is now also in print, with some content only available to subscribers of either edition. The website features news and analysis on an ongoing basis.

Sunkara is also a vice-chair of the Democratic Socialists of America, and he takes the “democratic” part seriously (“Any socialism we build will need to have a free, open civil society and multiparty democracy”, he recently tweeted). At the same time, you will find in Jacobin a perspective that is deeply critical of US mainline politics. On Bernie Sanders’ run, Sunkara predicted that Sanders would lose in the primaries, but that his run could be “an opportunity for movement building”.

In an interview with New Left Review, Sunkara articulated this focus on movement-building as core to his political philosophy: “What’s needed is to build movements until we reach a point where electoral options are actually viable.”

The organization behind Jacobin is a non-profit with about $300K in revenue in 2014. There is no Annual Report, which is not surprising for a tiny organization. In the aforementioned interview, Sunkara stated that most of this revenue is from subscriptions, with donations accounting for about 20% of the budget. In spite of its political radicalism, Jacobin is under conventional copyright terms (including back issues), and offers no discussion forums or other interactive components.

The print issue of Jacobin contains in-depth articles alongside beautiful graphic design (example issue). Unlike quite a few leftist magazines, Jacobin doesn’t engage in a lot of postmodernist piffle; its articles are often supported by charts and data, and tend to share a focus on issues that have real world relevance, including occasional departures into sci/tech themes like 3D printing or Silicon Valley politics.

So what can we find here that’s not reported elsewhere? Here are a few examples:

- an in-depth analysis of the prospects of the Kurds in Turkey, written by Djene Bajalan, an assistant professor with focus on Middle Eastern affairs

- a reasonable critique of Chuck Schumer, the prospective Democratic minority leader in the US Senate

- an analysis of the US media industry and the impact of the profit motive by Annenberg media studies scholar Victor Pickard.

One might wonder how a socialist magazine treats left-wing authoritarians. Will it applaud or rationalize as they restrict speech and political freedom, or will it criticize? The coverage of Cuban dictator Fidel Castro and Venezuela’s elected authoritarian Nicolás Maduro give us some idea. The Jacobin Castro obituary is in fact one of the better ones I’ve read, and is unambiguous in its criticism, for example:

“It was relatively simple to dismiss the calls for democracy from internal critics as imperialist propaganda, rather than a legitimate claim by working people that a socialism worthy of its name should transform them into the subjects of their own history. Public information was available only in the impenetrable form of the state newspaper Granma, and state institutions at every level were little more than channels for the communication of the leadership’s decisions.”

“An opaque bureaucracy, accountable to itself alone, with privileged access to goods and services, became increasingly corrupt in the context of an economy reduced to its minimal provisions. Castro’s occasional calls for ‘rectification’ removed some problem individuals but left the system intact.”

It concludes that “any socialism worth its name needs a deep and radical democracy.”

Jacobin’s coverage of Venezuela’s dysfunctional, corrupt and increasingly authoritarian government has been less robust and more likely to look for justifications primarily in the behavior of the right-wing opposition, though the article “Why ‘Twenty-First-Century Socialism’ Failed” by Venezuela-born socialist Eva María offers a more critical perspective which echoes the commitment to worker-focused democracy that defines Jacobin’s politics:

“The party, however, did not rely on its members’ active participation no matter how much Chávez liked to say it did. Instead, a bureaucratic structure, where criticism, open debates, and rank-and-file power were more often the exception than the rule, took over. The party formalized the bureaucratic layer of nominal Chavistas who were put in charge of different state sectors. In no time, this new caste engaged in corrupt behavior while continuing to deploy socialist rhetoric. The government’s ideas of funding and supporting popular power didn’t work in practice.”

The Verdict

Operating on a tiny budget, Jacobin offers a much-needed, intellectually coherent journalistic challenge to the prevailing social and economic order. The pitfalls of its political position are easy to pinpoint: the history of socialism and communism is riddled with failed economies, brutal autocrats and centralized bureaucracies, which calls into question whether its aspirations can ever be achieved in practice.

To build a mass movement for democratic socialism in the United States may seem like the remotest of possibilities, but the political successes of Bernie Sanders and the failure of the Democratic party to protect the progressive gains it has made under the Obama administration will lead many young people to search for alternatives.

Whether Jacobin can be a leading voice of that search for alternatives (within the two-party system, or outside mainline politics) will largely depend on whether it can maintain its commitment to a vision of radical democracy, consistently oppose political violence, and overcome any impulse to jump to the defense of authoritarian leaders who share some political objectives. The left is not immune to group polarization, and unreconstructed old-school socialists who habitually defend the indefensible are the political anchor around its neck.

I recommend Jacobin with reservations: read critically, it offers a useful complement to anyone’s diet of news and analysis. It is also aesthetically pleasing and edited with care, and their Twitter account is a good way to follow their work. 3.5 out of 5 stars, rounded up.

Founded in 2005 as a simple multi-author blog (Wayback Machine copy), ThinkProgress has grown into one of the more popular progressive news sites, with an estimated reach of 1.8M monthly uniques per Quantcast. Behind it is a powerful NGO with strong ties to some prominent players in US politics.

Organizational Structure, Funding

You may have never heard of the Center for American Progress, but it’s one of the most well-funded political nonprofits in the US, with over $45M in revenue in 2014. It was founded by none other than John Podesta, chair of Hillary Clinton’s 2016 presidential campaign and victim of a phishing attack of likely Russian origin on his email account.

CAP’s funding comes from foundations, corporations, individual major donors, and small donations. Its “Supporters” page provides a breakdown, and says that “corporate funding comprises less than 6 percent of the budget, and foreign government funding comprises only 2 percent.” Big foundation funders include the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the Ford Foundation, the Sandler Foundation, and George Soros’ Open Society Foundations.

CAP has a sister organization, the Action Fund. Unlike CAP, it is organized under the 501c4 section of the US tax code which permits political lobbying, but means that donations are not tax-deductible. It is a smaller organization, with about $8.5M revenue in 2015, the single largest chunk of which comes from CAP itself. The organizations also share the same CEO, Neera Tanden.

The Action Fund is the organization behind ThinkProgress, which is said to be fully editorially independent. Founder and editor Judd Legum left ThinkProgress in 2007 to join Hillary Clinton’s presidential bid as research director and then returned to his role, which is an example of the revolving door from CAP to the US Democratic establishment.

In 2015, Legum received total compensation of $199K from the organization, which is comparable to other nonprofit publications like Mother Jones.

Transparency

The ThinkProgress website is one of the worst we have reviewed in terms of disclosing organizational internals. The About page mentions its parent organization without even linking to it. There, with some luck, you may find the list of supporters; beyond that, the only reporting I was able to find on the organization’s work was a 10th Anniversary Report (and only with Google).

Considering the combined revenue of the two organizations, this is a remarkably poor level of transparency; much smaller organizations like Truthout manage to report regularly about their own work (reports) and make these reports easy to find.

Positioning, Bias

ThinkProgress describes itself as dedicated to “providing our readers with rigorous reporting and analysis from a progressive perspective”. Beyond that positioning statement, does it have bias toward specific politicians or policies?

Using the 2016 election as a yardstick, political connections notwithstanding, I did not find evidence of bias in favor of one of the Democratic candidates (Bernie Sanders or Hillary Clinton) in the coverage itself. Privately, the Wikileaks disclosures show that ThinkProgress editor Judd Legum did sometimes casually forward items of interest that could be used against Sanders (emails that include Legum and Sanders).

One exchange in particular caught the attention of right-wing critics. It was a heads-up by Legum that Faiz Shakir, a former ThinkProgress staffer, had started doing some work for the Bernie campaign. CEO Neera Tanden (Legum’s boss) reacted in a manner that can only be described as vitriolic.

It would be unfair to infer too much about ThinkProgress itself from these leaked private exchanges. They only serve to underscore the strong personal connections of some of its key players to the Clinton campaign. Now that the campaign is lost, it remains to be seen how these same players act in the changed political environment.

I would describe ThinkProgress editorially as left-of-center, which in the age of Trumpism makes them a useful source of adversarial journalism. Its content selection reflects a progressive perspective that is relatively free of reflection and squarely directed at the political right. In pursuing this agenda, the site sometimes overstates/sensationalizes slightly, but not as much as clickbait sites like Occupy Democrats do; more on this below.

Stories do appear to go through internal fact-checking (though the editors fell for a fake news site in 2014).

The site also engages in independent fundraising from readers, e.g., for its recently launched Trump Investigative Fund.

Content Examples

Consistent with its origins as a blog, ThinkProgress does not distinguish between news, analysis, or commentary. Some of its reports are in-depth investigative journalism that would be right at home on sites like ProPublica (e.g., its report on the growth of the sanctuary city movement since Trump’s election).

An example article that shows reasonable depth, while also not presenting any perspective that disagrees with its analysis: “Trump poised to violate Constitution his first day in office, George W. Bush’s ethics lawyer says”. See this NYT piece for a somewhat more balanced assessment of the same situation. This is a case where citing only a single perspective serves to slightly sensationalize reporting.

Similarly, when 46 US Attorneys were fired by the Department of Justice, ThinkProgress focused on framing the action as part of a larger purge narrative, not spelling out that Bill Clinton fired all 93 attorneys in 1993 (see the Vox reporting). This is an example of using a fairly ordinary political event as a “hook” to support a larger narrative.

As an example for overstating, one article calls the war in Yemen a “climate-driven war”. While the article itself makes good arguments, that summary overstates the role of climate change (compare this analysis by International Policy Digest).

Sometimes the site does use clickbait tactics. The headline “SCOTUS nominee Neil Gorsuch faces extraordinary sexism allegation from former student” uses ambiguous language which could describe a wide range of behaviors in order to sensationalize Gorsuch’s alleged comments about maternity leave.

Worse, these comments are disputed by several other students (see NPR coverage, or National Review for the right-wing perspective). This isn’t mentioned in the article, and ThinkProgress kept tweeting the piece at least until March 24, when other media had already reported the dispute.

Design, Licensing

ThinkProgress design in 2005, 2011 and 2017 (old screenshots courtesy of archive.org).

The ThinkProgress website is a branded version of Medium, with all the associated advantages and disadvantages (e.g., it works poorly without JavaScript, but looks nice on mobile and has decent built-in social features such as commenting, notifications and following).

Content is under conventional copyright, with permission to re-use granted on a case-by-case basis.

The Verdict

While I would not put it in the same journalistic category as publications like Mother Jones or The Intercept, I do recommend following ThinkProgress on Twitter or by other means as a source of progressive advocacy journalism. At its best, ThinkProgress provides valuable in-depth investigative reporting.

The complex influence web behind CAP and the parent organization of ThinkProgress raises questions about how autonomously it can operate, but one shouldn’t overstate the case. The organization it is not dependent on a single funder and relies on public support, as well. Perhaps ThinkProgress would better served being a truly independent organizational entity, which would also enable tax-deductible donations.

The rating is 3.5 stars, rounded down. Points off for a slight tendency toward sensationalizing (primarily through framing and selective reporting) and a lack of transparency.

(Updated in March 2017 with new information and to be more consistent with our review methodology.)

Democracy Now! is one of the best-known progressive news sources in the United States. It has been around since 1996 and is distributed online as well as through broadcast television and radio. It is identified strongly with co-founder, principal host and executive producer Amy Goodman, an investigative journalist known for courageous confrontations with powerful economic and political forces. Most recently, Amy Goodman was in the news because an arrest warrant was issued against her in connection with her reporting on the Dakota Access Pipeline. The case was quickly dismissed but helped bring further attention to the protests.

The organization running the show is a non-profit, though it does not appear to publish an Annual Report (none is listed on the website, and an email request has so far not been answered). Its revenue for 2014 was $6,674,958, so the lack of transparency about impact, strategy and spending is a bit unusual for an organization of this size. Indeed, Charity Navigator rates it at two stars for accountability and transparency, due to the lack of audited financials or information about its board of directors.

The primary content the organization produces is a Monday-to-Friday one hour broadcast (in English, with some content translated to Spanish) that typically consists of news and interviews. With a progressive lens, the show gives more attention to issues that typically only get second-tier coverage in mainstream media, such as international efforts to combat climate change, or left-wing social movement activism. This is done in a dry and muted “just the facts” tone.

The show is always smart, sometimes tedious (interview guests are hit or miss; breaks with music or monotonic monologue are not for everyone), sometimes engaging (like when it tackles challenging conversations, such as discussions about third party candidates).

An example of clever journalism, even if one disagrees with it: during the 2016 election, Democracy Now! staged a reenactment of one of the US presidential television debates, giving third party candidate Jill Stein (who was not permitted to participate) the opportunity to answer the same questions the main candidates were asked. (The libertarian candidate was also invited, but could not make it.)

The overall curation of topics is quite remarkable, and the emphasis on stories not receiving attention by major media makes Democracy Now! a good addition to any news and information mix, if the video/audio format works for you. There is textual content on the site, but much of it is transcripts or very short blurbs.

Personally, I prefer to read the news, as do young people who have grown up with the web. But the Democracy Now! broadcast reaches audiences who may not be deft navigators of the web, and therefore is an important part of the US political media landscape.

The online version of the show does offer links to different segments and transcripts so you don’t have to watch to or listen to the whole show. But of course content that is native to the web offers many other possibilities that are underutilized in a TV/radio show transported to the web – conversation and participation, interactive data and charts, cross-referencing, embedded videos, tweets and other content, and so forth. This also gives Democracy Now! a disadvantage in social media that rely on content that’s optimized for being shared.

The Verdict

Democracy Now! is a fine example of viewer-supported journalism. It is constrained by its format and perhaps to an extent by its ambition. It is a brainy daily roundup that appeals to people who already self-identify as progressive, but is unlikely to convince people who are not. Many will background the broadcast to other activities rather than intently listening for an hour (a podcast version is available).

The lack of organizational transparency is disappointing for a non-profit, though not surprising for an organization that’s clearly monomaniacally focused on its mission. In spite of those reservations, Democracy Now! deserves four stars for its tireless dedication to quality journalism and to the pursuit of major stories and topics that are neglected elsewhere. Even if you don’t identify with the (by US standards) far left political lens of the broadcast, including frequent spotlighting of third party candidates, it enriches our perspective on the world in ways other sources rarely do.