Reviews by Eloquence

We have a tendency to view history in chapters with clear boundaries (“World War II”, “The Cold War”, “Late Capitalism”). But as William Faulkner’s immortal words remind us: “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.”

Along with Michelle Alexander’s The New Jim Crow (review), Ari Berman’s “Give Us the Ballot” is a crucial work published prior to the election of Donald Trump yet essential to understanding it, not as an anomaly but as a continuation of a past that isn’t dead—or past.

Ari Berman is a senior contributing writer for The Nation. His book is a meticulously researched history of voting rights in the United States, with focus on the period from the 1960s to the final years of the Obama administration.

Based in significant part on interviews with more than 130 individuals, including iconic civil rights figures like the late Julian Bond and Rep. John Lewis, Berman’s book brings to life the bloody, sometimes lethal struggles of African-Americans and Latinos to participate in American democracy.

Yes, you will find here a history of the Selma to Montgomery marches and graphic descriptions of racist figures like Jim Clark, whose infamous posse terrorized American citizens with whips and cattle prods. You will find a clear explanation of the landmark Voting Rights Act of 1965 and its enforcement. But far more important is Berman’s research into what happened in the following decades.

The front page of the New York Times after “Bloody Sunday” in Selma, Alabama

A History of Counterrevolutions

First, Berman shows the many attempts, especially by southern states, to circumvent the law. From refusing to seat elected black legislators to messing with district boundaries and changing election rules, every dirty trick was tried to maintain white supremacy.

Second, the book makes it clear that, at least for a while, a bipartisan consensus in Congress helped protect the right to vote against many of those efforts. Ultimately, it was the Supreme Court, not Congress, that declawed the Voting Rights Act, just when it was urgently needed again (Shelby v. Holder).

Finally, Berman documents how the Republican Party (GOP), as the inevitable consequence of the Southern Strategy it embraced in the 1960s, became the party of voter suppression and racially charged stereotyping. Minorities and low-income voters overwhelmingly vote for Democrats, so whether or not GOP legislators harbor any racist sentiments, strategies that effectively suppress the vote of those demographics help GOP candidates.

As Heritage Foundation co-founder Paul Weyrich put it chillingly in a 1980 speech to evangelicals (video courtesy of PFAW; the quote also appears in the book):

I don’t want everybody to vote. Elections are not won by a majority of people, they never have been from the beginning of our country and they are not now. As a matter of fact, our leverage in the elections quite candidly goes up as the voting populace goes down.

Since then, the rhetoric has shifted to “election integrity” and “voter fraud” to justify arbitrary changes to voting rules (including elimination of reforms like early voting or same-day registration) and voter ID requirements that disproportionately impact poor people and minorities. Beyond citing the facts, Berman illuminates them through personal stories (page 307):

During the state’s municipal elections in November 2013, [Texas voter Floyd] Carrier, an eighty-three-year-old who had been an army paratrooper in the Korean War, brought his expired driver’s license, VA card, and voter registration card to the polls in China, Texas, where he’d lived and voted for sixty years.

The poll workers immediately recognized Carrier but would not let him vote because, they said, he didn’t have a valid voter ID. “I felt terrible,” Carrier told the court, “because all I did for my country and they turn me down, so I just felt like I wasn’t a citizen anymore.”

I was moved to tears by some of these stories. As horrific as the brutal voter suppression of the Jim Crow era was, the slow unraveling of progress that has been won almost feels worse. But by telling the stories of how people fought back in the past and how they are doing it today, Berman maintains our belief that positive change is possible—it is just not guaranteed.

This book is not always an easy read: there are no illustrations, photos, maps, graphs, or tables to provide visual or quantitative context (statistics like turnout and registration data are always cited in the flow of the text), and Berman’s journalistic approach of introducing person after person after person doesn’t easily translate to a 300+ page book. I found myself repeatedly scanning back for the mentioned names, “who is this again?”

But the payoff is worth it. “Give Us the Ballot” is a crucial history for any political conscious American citizen or resident living now under a President who regularly flirts with autocrats and white supremacists (and happily uses their talking points), and who has launched a thinly disguised federal voter suppression effort. To fight back against this well-organized effort to dismantle democracy, arm yourself with the facts.

Language Transfer is one of those projects that represent the Internet at its best: a passionate individual (Mihalis Eleftheriou) and a community of volunteers creating free learning resources for the whole world. Mihalis may well become known as the Sal Khan of language learning, but unlike the well-endowed Khan Academy, the project is entirely funded through small donations, primarily via Patreon.

The LT courses are audio lessons. Mihalis interacts with a student. As you listen, you pause at relevant points to provide your own answer, then compare it with the student’s (and, if different, with Mihalis’ response). There are courses of different degrees of completion in French, Swahili, Italian, Greek, German, Turkish, Arabic, Spanish, and English (for Spanish speakers).

In effect, a 10 minute audio file may take you 15-20 minutes to complete. I don’t recommend listening to these courses in the background. They deserve your undivided attention. The courses are carefully edited, so it never feels like you’re wasting time.

I’ve completed the 90 track “Complete Spanish” course and can say that, of all the language learning resources I’ve used in the last year (Duolingo, Lingvist, Mango, and various books), it’s been the most helpful one in helping me understand the language rather than just memorizing words or attempting to intuit rules on my own.

Seeing the connections

Learning a language primarily through memorization can be frustrating. It takes forever to feel like you’re making progress, and irregularities can quickly break your memorization patterns. Instead, Mihalis’ approach is to help you see the connections between languages, and the rules and patterns within them.

This can provide immediate payoff. For example, in the “Complete Spanish” course, Mihalis spends some time early on showing how, in thousands of cases, Spanish words can be constructed from English ones that share the same Latin origin. Rather than spending a lot of time building the initial vocabulary, Mihalis then uses many of these words to construct the first sentences.

Where possible, he explains why exceptions and irregularities exist: vowels that got swallowed over time, words that were transferred into Spanish from a different language like Arabic or Greek, accents that help to avoid ambiguity. He also points out negative language transfer—cases where we may be tempted to mistakenly use rules we’re familiar with. Listen to this example:

Advice like this is incredibly helpful and often omitted in other learning resources. Similarly, Mihalis adds important context about the regional differences (“you may hear it said this way, or that way”). When dealing with difficult parts of the language, like the subjunctive in Spanish, he helpfully reminds us that these are the exciting moments of learning a language: when you become able to express something in a wholly new way.

What’s so powerful about this approach is that it reflects the reality of how languages have spread and developed over time, through human migration, trade, conquest, and local customs. Seeing the connections between languages like English, Spanish and Arabic makes it easier to recognize jingoism and cross-cultural prejudices for what they are.

I recommend Language Transfer without any reservations, by itself or as a companion to other learning resources. You can play the audio files on the site or download them, including via official .torrent files (here’s the Spanish one). And if you get value out of it, consider making room in your donations budget for a monthly gift.

This story of a year in the life of Jason Taylor, a thirteen-year-old English boy, is one of David Mitchell’s most down-to-Earth books, subtle but not simple. Full of beautiful vignettes and aphorisms (Taylorisms?), Black Swan Green is at times to funny and evocative that it made me laugh out loud while reading. The year is 1982, Great Britain is about to enter the Falklands War, and Jason is a stammering, confused kid who writes poetry and is trying to make sense of his world.

David Mitchell can’t quite resist sometimes pushing Jason Taylor aside and taking over in his own voice, causing dissonant ripples in the story’s flow. But when Jason’s voice comes through loud and clear, Mitchell succeeds in revealing the timeless sense of wonder behind the papier-mâché mask of our adulthood. 4.5 out of 5 stars, rounded up.

Abyss, published in 2001, is the third novel of the “DS9 relaunch”, a series of books and comics that continue the story of Star Trek: Deep Space Nine beyond the excellent television series, which ended after 176 episodes in 1999.

Abyss focuses on Doctor Julian Bashir’s continued entanglements with the mysterious and amoral intelligence agency that calls itself “Section 31”. In a galaxy where many planets, including Earth, have chosen the path of cooperation through the United Federation of Planets, Section 31 claims to quietly do the Federation’s “dirty work” necessary to keep the peace—even if it involves mass murder.

Section 31 recruits Bashir on a mission to subvert a secret base run by a genetically enhanced scientist like himself. (Bashir, for his part, hopes to also collect information to take down Section 31.)

In Star Trek’s alternative history of Earth, genetic engineering ultimately led to the Eugenics Wars, where enhanced “superhumans” nearly destroyed the planet. After the wars, genetic enhancement became taboo, and those who (like Bashir and his adversary) live with such enhancements are regarded with suspicion.

Bashir tried to use his talents for good, while his opponent appears to more interested in using his expertise to breed an army of super-soldiers and take on the Federation.

The premise is interesting enough, and much of the story is quite captivating. Unfortunately, the book loses steam in its final third. Neither Section 31 nor Bashir’s confrontation with his enemy really get the space they deserve. Instead, the book spends a bit too much time on an Avatar-style subplot of an oppressed local population, and on Ro Laren (who is DS9’s security officer in the relaunch, and a part of Bashir’s team for the mission) being angry.

Bashir fans will likely still enjoy this novel, and it integrates nicely into the DS9 relaunch series. Personally, I would give it 3.5 out of 5 stars, rounded down—a solid premise, well-paced, but limited resolution and payoff.

David Mitchell, best known for Cloud Atlas, can be a difficult writer to appreciate. In the same book, he often hops from genre to genre: crime, fantasy, sci-fi, horror, you name it. With books like Thousand Autumns, you think you’re reading historical fiction, but then it turns out that there’s a supernatural component, which then ties into his larger fictional universe. In many of his novels, there’s a lot to unpack before you get to the payoff.

With Slade House, Mitchell delivers something much simpler: a straightforward horror story. And this one really packs a punch. It’s a tale of a haunted house that is also a feeding ground—and those who enter are the food. While Slade House very explicitly ties into the story told in his previous novel, The Bone Clocks, this isn’t a sequel. It’s more of a brief, optional detour during the larger epic Mitchell appears to be weaving.

Through a set of short sequences set years apart from each other, Mitchell manages to really drive the horror of Slade House home in a way that I can only describe as “gut-wrenching”. Don’t expect too much from this short book—think of it more like one of Stephen King’s better horror novellas. This is no Cloud Atlas, nor does it pretend to be; nonetheless, I found it well worth the quick read. 4 out of 5 stars.

What literary scholar Jonathan Gottschall is attempting to do here may seem quixotic: to pin down what makes stories such powerful drivers of human action, often by using more anecdotes and stories to do so.

From the often violent stories children make up to the wild tales our brains concoct while we sleep, Gottschall does make a good case that stories relate crucially to our survival. They often help us imagine worst-case scenarios, to play through possibilities, or to think ahead. Modern manifestations of story consumption, from binge watching Netflix to playing video games, may appeal to us simply because they plug into a “hardwired” readiness to invent and imagine.

References to studies are sprinkled across the book. Some of the science will likely be familiar to many readers, from the bizarre findings of split-brain research to Elizabeth Loftus’ well-known investigations of the fallibility of human memory. These examples are used to illustrate the brain’s remarkable tendency to confabulate.

To further explore the dark side of our storytelling habit, Gottschall relates the case of James Tilly Matthews’ paranoid delusions about a group of villains known as the “air loom gang”. But he casts Matthews’ fascinating delusions into the format of a short fantasy story to make the point that creativity and madness have much in common.

A discussion of conspiracy theories, including Alex Jones’ notorious Infowars website, and of the delusions that motivated some of history’s darkest figures adds to these observations. If Gottschall had written this book during or after America’s fateful 2016 election year, he might have attempted to equip the reader with better self-defense tools against propaganda and made-up nonsense.

As it is, the author’s objective here is simply to examine what makes stories special in our minds That question relates so deeply to the foundations of our emotional experience of the world that the answer is perhaps bound to be a little unsatisfactory to knowledge seekers. If, on the other hand, you’re simply looking for a good yarn about stories, you may get a kick out of this one. 3.5 stars, rounded down since I was hoping for more knowledge and less story.

There are countless science books for kids, teens and lifelong learners, with titles like “How Much is a Million?” or “Tiny Creatures: The World of Microbes”. The best of these books celebrate wonder and the beauty of elegant explanations. Most avoid the rocky terrain of religion and spirituality. Why limit the audience of a general science book by engendering controversy and criticism?

But Richard Dawkins is no stranger to controversy. With books like “The God Delusion”, he has become a leading figure of the New Atheist movement. As an evolutionary biologist, he has been especially concerned with the religious efforts, sometimes masquerading as science, to promote creationism and undermine science. His book “The Greatest Show on Earth: The Evidence for Evolution” (reviews) remains one of the best general introductions to evolutionary biology I know.

“The Magic of Reality”, as its title suggests, has an even larger scope: it seeks to foster curiosity and contrasts scientific explanations for life, the universe and everything with mythology. Its target audience are teens, though the book is readable with some help by younger kids and enjoyable for older readers as well.

The book is richly illustrated by Dave McKean, whose previous work has helped bring to life stories by Ray Bradbury, Neil Gaiman, and Stephen King. You may want to invest in (or borrow) the hardcover edition, which gives the photos and illustrations the space they deserve.

Given its large scope, the selection of topics in “Magic” is necessarily somewhat arbitrary. The chapter headings are:

-

What is reality? What is magic?

-

Who was the first person?

-

Why are there so many different kinds of animals?

-

What are things made of?

-

Why do we have night and day, winter and summer?

-

What is the sun?

-

What is a rainbow?

-

When and how did everything begin?

-

Are we alone?

-

What is an earthquake?

-

Why do bad things happen?

-

What is a miracle?

Most chapters begin with myths, and biblical myths get no special treatment here: stories by “Tasmanian aborigines” are told side-by-side with those of “the Hebrew tribes of the Middle East”. This diversity is very refreshing, and the illustrations help the reader to immerse herself in each myth or story.

This is followed by Dawkins’ best shot at an explanation for the “real story”, ranging from evolution by natural selection to tectonic plates, the refraction of light, or the Earth’s tilted axis of rotation relative to its orbital plane.

A few times, Dawkins writes things like this:

Well then, does our quest to cut things ever smaller and smaller end with these particles: electrons, protons and neutrons? No—even protons and neutrons have an inside. Even they contain yet smaller things, called quarks. But that is something I’m not going to talk about in this book. That’s not because I think you wouldn’t understand it. It is because I know I don’t understand it.

Dawkins’ willingness to admit ignorance and uncertainty, too, is refreshing, though there are times when then book would have benefited from a co-author with a different background (a physicist, for example) to flesh out an explanation. The quoted passage is perhaps one of those times: quantum physics is wild and beautiful enough to deserve more space in a book about the magic of reality.

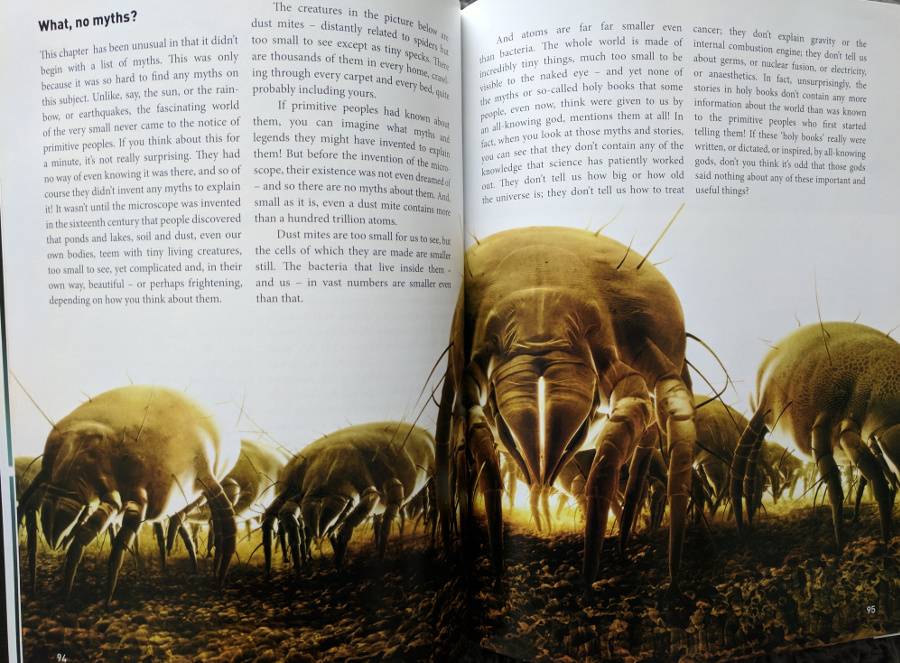

Almost every page is illustrated with photographs or drawings. Most chapters begin with stories from mythology, but when talking about things that are small to see with the naked eye, Dawkins points out the notable absence of myths that predict or describe them.

Dawkins does succeed in making connections between the chapters, but overall, some topical transitions are a bit abrupt (“let’s talk about life on other planets - now let’s talk about earthquakes”).

Throughout the book, Dawkins acknowledges the beauty of myth while contrasting it with the “magic of the real”. He is especially critical of flimflam artists who try to convince people of supernatural powers, while his criticism of religion is not as pronounced and explicit as in some of his other works.

In the last chapter (“What is a miracle?”) the book echoes Carl Sagan’s “The Demon-Haunted World”, conveying similar lessons about critical thinking to a younger audience. Where Sagan gave his readers a “Baloney Detection Kit”, Dawkins uses a few simple examples (e.g., the Cottingley Fairies, the Fatima apparitions) to contrast the belief in miracles with more plausible explanations.

The Verdict

“The Magic of Reality” is a beautiful book, and I can recommend it as a gift, especially to curious younger people, or as a refresher intro to some basic scientific observations about the world we live in. It leaves the reader hungry for more, which is one of the best things one could ask for from a science book for young audiences. Its willingness to contrast science and myth makes it a relatively rare treat.

My main criticisms are that the book would have benefited from a bit more physics content, and more work on the overall narrative structure (through chronology, scale, historical figures, or some other structuring device). Recommended; 4 out of 5 stars.

In the social and political upheaval of the 1960s and 1970s, many socialist and progressive publications were born. Most are long gone; New Internationalist, founded in 1973 in the UK, is a notable exception. Not only has it survived well into the 21st century, it has proven its adaptability through a crowdfunding campaign that raised more than $900K in donations.

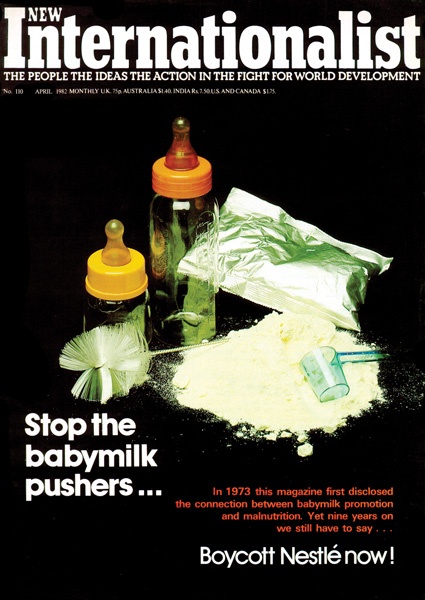

Through its history, the publication has focused on liberation and decolonization movements around the world and on the global impact of unbridled capitalism. It was one of the first publications to highlight the dangers of Nestlé’s efforts to market infant formula milk in the developing world; decades later, it played a similar role in raising awareness of fracking.

A significant part of New Internationalist’s ethos is to “give space for people to tell their

own stories”, that is, to feature international writers instead of Western “experts” and correspondents. This helps to lend an authenticity to its reporting that many other publications lack.

The provocative April 1982 cover of New Internationalist, revisiting the issue of infant formula milk.

New Internationalist also operates the Ethical Shop, which sells books, calendars, clothing, and various other merchandise. This includes original publications, such as the series of “No-Nonsense Guides” on topics ranging from global finance to drug legalization. Other products are sold together with partner charities. The shop follows a Buying Policy that seeks to promote good labor and environmental practices.

While it tends to support left-wing politics, New Internationalist is not an explicitly socialist magazine.

Finances, Transparency, Impact

Many of the US-based nonprofit media we have reviewed are dependent on grants, awarded from the fortunes amassed by the likes of Bill Gates, Michael Bloomberg, George Soros, Herbert Sandler, or previous generations of industrialists. This can create a bias towards elite audiences and away from highly contentious topics (see, e.g., Rodney Benson: Can foundations solve the journalism crisis?).

In contrast, the revenue supporting New Internationalist comes from people buying digital and print publications, or ordering other products from the Ethical Shop. This is broken down in percentages in the 2013/14 Annual Report, which does however not include GBP (£) figures. Indeed, the New Internationalist website includes no direct reference to organizational internals, and I did not receive a response to a contact inquiry asking for more recent information.

This lack of transparency is all the more regrettable given that the organization is run as a co-op with a non-hierarchical structure, very unlike the top-down model that is typical for US nonprofits. The rest of the world would benefit from learning more about this approach from those who practice it.

The UK Companies House report for New Internationalist Publications Ltd. shows net assets of 853K GBP (about 1.15M USD) as of March 31, 2016.

As of this writing, New Internationalist has about 37.8K followers on Twitter and about 80K on Facebook. These numbers should have some room to grow; consider, for example, that Positive News (also UK-based, also a co-op, with a smaller budget and smaller print circulation) has about 260K Facebook followers.

Design and Apps

The New Internationalist website is a minimalist feed of articles that mixes shorter posts and features, without any apparent prioritization beyond recency. Stories are tagged with regions and topics, which can be used to explore the large library of articles. The site is reasonably mobile-friendly. Some readers may have difficulty with the relatively low contrast color scheme (an unfortunate recent design trend).

As with many publications from the print era, only a subset of New Internationalist content is available for free online. If you prefer digital over a print subscription, you can purchase and read the magazine on Android or iOS devices via the respective apps (New Internationalist for Android, New Internationalist for iOS).

The Android app works well enough, though there are a few annoyances; for example, wide tables require horizontal scrolling, but accidental “swipe” gestures trigger moving from one article to the next, making it almost impossible to actually view wide tables. On the plus side, the article text is readable, and tables are presented as tables rather than as embedded images.

You can purchase full copies of the magazine via the Android and iOS apps.

An alternative to buying copies through the apps is purchasing them through Zinio and reading the magazine through its dedicated reader. As far as I can tell, there is no option to purchase and download DRM-free PDF files, and I found no evidence that any part of New Internationalist (web or app) is developed as open source software. New Internationalist articles are under conventional copyright (as opposed to a Creative Commons license).

Content Example: “The Equality Effect”

While not all content is available for free, many feature stories are posted in full. “The Equality Effect” is such a feature story, written by Danny Dorling, Professor of Geography at the University of Oxford and author of a book with the same title. In fact, much of the July issue was dedicated to the issue of inequality and edited by Dorling.

The article is analytical, making the case that inequality is the source of a large number of social ills, and not at all unavoidable. Rather than promoting a specific political ideology, Dorling is making a case to consider policies addressing inequality on their merits:

Although leftwing and green politicians tend to advocate greater equality more vocally, and rightwing and fascist ones tend to oppose it, equality is actually not the preserve of any political label. Great inequality has been sustained or increased under systems labelled as socialist and communist. Some free-market systems have seen equalities grow and the playing field become more level. Anarchistic systems can be either highly equitable or inequitable.

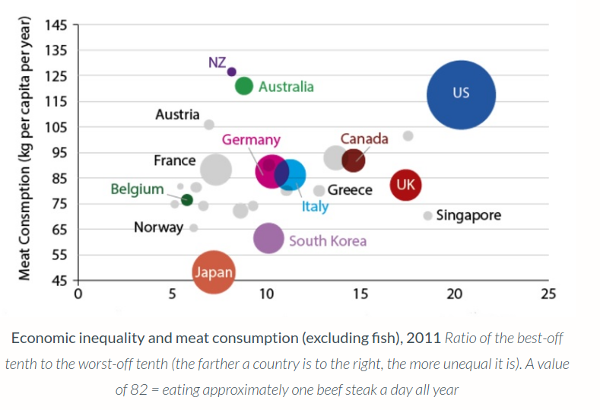

At the bottom of the article is a carousel of “related articles”, some from the same issue. It’s easy to miss that Dorling wrote another piece in the July issue expanding on his argument: “The rich, poor and the earth”. It cites additional data and attempts to show correlations between inequality and waste production, CO2 emissions, and meat consumption.

As presented, this chart does not support the thesis of the article that inequality is meaningfully correlated with meat consumption, let alone that there is a causal relationship.

Skeptical readers will find the analysis here to be lacking in rigor. Dorling dismisses outliers; in the case of the “meat consumption” chart, France, Germany, and the UK show very similar levels of meat consumption in spite of large differences in inequality. Eliminate the US and even the appearance of a correlation largely disappears; in any case, a correlation coefficient is not given.

With these kinds of charts, there are many ways to demonstrate the result you want: by cherry-picking countries, by picking the measure of inequality that shows the strongest correlation, and by only considering alternative explanations for data points that disagree with the hypothesis (“their cultural histories are bound up with the rearing of sheep and cattle”).

Data scientists warn that much more visually compelling spurious correlations can be found between many completely unrelated measures, and that even peer reviewed science is routinely subject to data dredging and p-hacking. “Science isn’t broken, it’s just a hell of a lot harder than we give it credit for,” warned a must-read article by FiveThirtyEight science writer Christie Aschwanden.

The thematic focus on inequality is laudable, and it makes sense that New Internationalist would invite an accomplished academic writer on this topic as guest editor. In fact, the much larger Guardian also published Dorling’s bubble chart analysis uncritically. Still, we should expect a greater level of empirical rigor in unpacking complex issues such as this one.

Content Example: “The Many Roots of Homelessness”

“Civil war, mental illness, poverty, gang violence: the many roots of homelessness” is a more conventional storytelling piece from the June issue that shares personal narratives of people experiencing homelessness and housing insecurity from the Philippines, Great Britain, the United States and, Mexico.

This short article showcases New Internationalist’s strength in featuring authentic voices from around the globe. For example, Maria from the Philippines describes the economic pressure which forces her family to live in a slum:

We found a room for rent in the nearby block. It cost $50 a month. It’s expensive and eats a huge chunk of Marvin’s monthly income of $119. I can’t work yet because I have to take care of our baby, Mark. So this is our home for now.

This kind of storytelling is crucial to overcome stereotypes and to challenge the stigma often associated with homelessness.

The Verdict

New Internationalist is important: it sheds light on underreported injustices and amplifies the voices of activists who seek to bring about positive change. As a left-wing publication, it occupies a relatively lonely space by taking an impact-oriented international view without being stridently ideological.

It has outlasted many other magazines and successfully made its way into the 21st century, but not without stumbling. The website and apps still have a few mostly minor bugs; the site design suffers from small readability issues and lacks clear organizing principles; the level of transparency is below some other mature nonprofits of similar size (compare Truthout’s timely and comprehensive Annual Reports, for example).

You will find many stories here that nobody else is covering, with larger ambition and reach than other publications we’ve reviewed, and the editorial quality is generally high. When tackling complex topics, New Internationalist would benefit from more rigorous internal review to ensure the highest possible quality of reporting. Recommended; 4 out of 5 stars.

Founded in 2009 by Luis von Ahn of reCAPTCHA fame, Duolingo has quickly become the most popular free language learning tool, reaching some 150 million users today. Is it any good? The short answer: yes, but if you’re serious about learning a language, use it in combination with other resources.

After you sign up, the core experience is a set of interactive exercises focusing on different areas of a language: basic vocabulary, sentence structure, past and future verb tenses, and so on. Learning takes place along a sequential path, but you’re encouraged to repeatedly practice previous lessons.

Standard exercises include

-

practicing vocabulary using photographs (sort of like flash cards)

-

translating sentences in either direction

-

writing down what you hear

-

multiple choice quizzes of the “pick the correct translation(s)” variety

-

speaking sentences in the language you’re learning (the automatic validation errs on the side of marking your pronunciation correct)

This variety keeps the lessons interesting, though even after months of use, I still sometimes translate when I’m supposed to be transcribing. The mobile app minimizes the amount of typing by letting you “tap together” sentences rather than writing them, easing the difficulty a bit in favor of keeping things user-friendly.

One huge plus is that Duolingo is generally pretty good at accepting multiple translations for the same phrase. Sure, users still complain about correct translations not being accepted, but compared with language learning applications I’ve tried in the past, it handles the very large solution space pretty well, at least in Spanish.

Speaking of user comments, every exercise is linked to a discussion forum, which often contains helpful tips, both from other learners and native speakers.

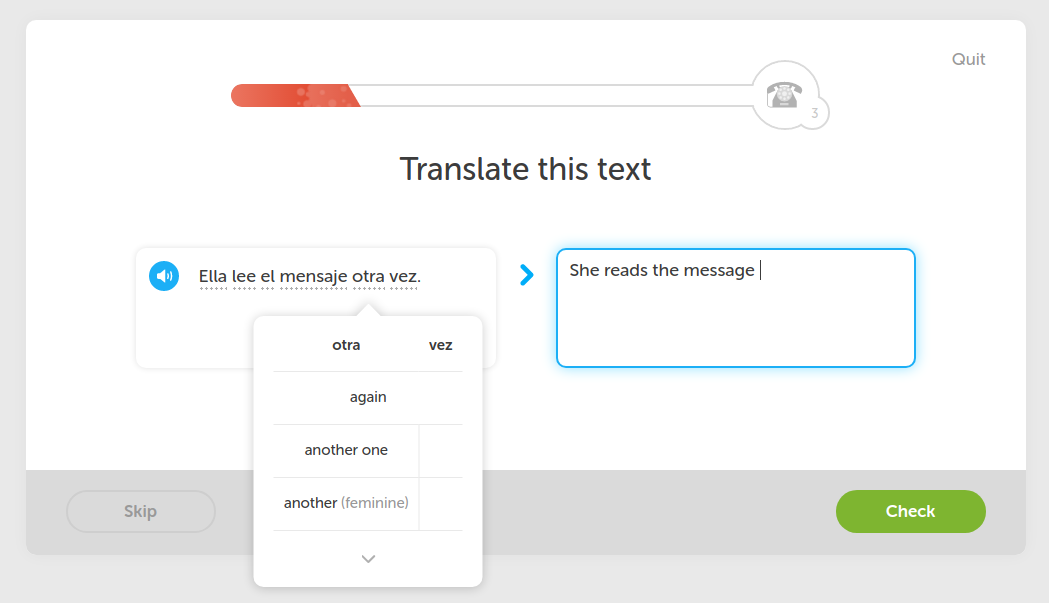

A typical Duolingo lesson will include translation exercises like this one. The UI is streamlined so you never really get stuck — you can always quickly refresh your memory through built-in hints.

Duolingo is well-funded and its product designers and engineers routinely launch new experimental features. For example, as of this writing, the “Labs” section features Duolingo Stories, which are interactive, spoken short stories where you complete sentences as you go. The iOS app, meanwhile, is currently experimenting with chatbots.

This is all well and good, but the core product isn’t receiving nearly as much love. Aside from the exercises, there’s very little context that helps you to learn about grammar or the internal patterns of the language you’re learning. Some lessons include some instructive text, which tends to be both minimal and not very well-written. And once you’re done with the lessons (which, for Spanish, took me a few months), you’re still at very limited proficiency with nothing else to do but to practice or to try more “Labs” projects.

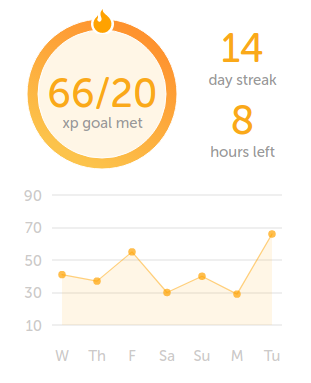

Gamification is a core part of the Duolingo user experience. The site tracks your daily usage, rewards you for completion of lessons, and sends you (genuinely helpful) reminders to keep at it.

On the positive side, the gamification — daily reminders, XP scores, levels, gemstones, etc. — does work to develop a language learning habit. Even aspects that may seem excessively silly (the mobile app lets you dress the Duolingo mascot in fancy clothes with the gemstones you’ve earned) do increase the user’s emotional investment in the learning process.

The business model is advertising (earlier plans to monetize translations notwithstanding), and the company has so far generally maintained a “not evil” reputation. You can even turn off the ads by paying a monthly fee, though most users will probably not find that to be worth it. With a high valuation and repeated injections of huge amounts of funding, let’s hope Duolingo continues to follow the straight and narrow.

I recommend Duolingo wholeheartedly — just don’t expect that it’ll be enough to get you from novice to pro. Use it in combination with books, videos, or free courses like Language Transfer. If you live in a big city, face-to-face Meetup groups can also be a great way to find other language learners and native speakers.

I remember well the chills I felt listening to Barack Obama’s victory speech from Grant Park in November 2008. As a recent immigrant to the United States, it seemed like I was witnessing an important new beginning for a country that had struggled with the legacy of slavery and segregation for so long.

Two years later, legal scholar Michelle Alexander published The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness, taking stock of America’s criminal justice system and issuing a warning against premature optimism in light of Obama’s victory. As the title suggests, Alexander’s book links America’s globally unique system of mass imprisonment with the decades of post-slavery segregation, discrimination and voter suppression known as the Jim Crow era (named after a racist blackface caricature).

The new racial caste system

Alexander’s thesis is that the system of segregation has simply been replaced by another racial caste system, one which is compatible with America’s newly found ethos of “colorblindness”. Through the “War on Drugs” and related “anti-crime” campaigns heavily targeting poor, black communities (without a plausible justification for this racial bias), the United States swept millions of African-Americans into the criminal justice system.

Massive sentencing disparities such as the whopping 100:1 weight ratio determining crack cocaine vs. cocaine sentences (reduced to 18:1 with the Fair Sentencing Act) kept them there for much longer. Upon release, they are stuck with felony records that are the basis for legalized discrimination ranging from voter disenfranchisement in some states, to housing and employment discrimination. They are a despised underclass which anyone can hate without repercussions.

Through one Supreme Court decision after another, apparent constitutional protections have been eroded at every step of the way — from racially biased policing to unfair sentencing and all-white juries. On page 119 (2012 paperback edition), Alexander notes poignantly:

It is difficult to imagine a system better designed to ensure that racial biases and stereotypes are given free rein—while at the same time appearing to be colorblind—than the one devised by the U.S. Supreme Court.

This system, which never exclusively targets African-Americans but is heavily biased against them, has been established by both Democrats and Republicans. Its foundation was laid by Ronald Reagan and his new “War on Drugs”, while mass incarceration itself was perfected by Bill Clinton’s “tough on crime” administration.

Michelle Alexander supports these observations with countless studies and statistics. Her writing is provocative but always grounded in the facts, and her conclusions are inescapably correct.

Importantly, Alexander notes that the “new Jim Crow” is not simply a “gentler” successor to the system of racial segregation that preceded it; it is in many ways more pernicious. Millions have been demonized and caged like animals. But because the system operates largely without open declarations of racist beliefs, it is difficult to challenge or even talk about without predictable “then just don’t commit crimes” responses (ignoring that white people go free for the same crimes that black people are punished for).

The system endures

Since Alexander’s book was published, no major criminal justice reform has been implemented, and America continues to lead the world incarceration rankings. Its prisons are known for human rights abuses, from shackling pregnant women (even during delivery) to forcing prisoners to endure extreme heat (and sometimes die from it). It practices solitary confinement for long periods under horrific conditions, and even forces prisoners to share cells designed for solitary use, leading to predictable results.

Barack Obama was succeeded by a far-right reactionary with open sympathies for white nationalists and other despicable groups. Indeed, Donald Trump ran a playbook “law and order” campaign frequently employing racist stereotypes, primarily targeting immigrants. After losing the popular vote by millions, he was swept into office by an electoral system that was designed to boost slave-owning states’ voting power based on how many slaves they owned.

The new Attorney General, Jeff Sessions, is keen to reboot the War on Drugs once more, and has already reinstated harsher sentences for low-level drug offenses. For-profit prisons, police militarization and civil forfeiture are en vogue again. Together, these measures ensure that mass incarceration will be with us for years to come. And by pardoning indisputably racist, vile and criminal Sheriff Joe Arpaio, Donald Trump himself has sent a clear message about his expectations from law enforcement.

An essential guide to an ugly reality

New developments notwithstanding, seven years after the first edition, Alexander’s book remains an essential guide to uncovering the reality of America’s new system of racial control. It is a difficult, painful read, but it opens our eyes to the scale and severity of this challenge.

Though written by a legal scholar, Alexander is critical of tunnel vision and the “NGO-ization” of liberation movements. Indeed, if you previously thought that the US Supreme Court is on the side of moral progress, this book will convince you that it all too frequently simply bolsters the prevailing systems of control. Though Alexander advocates no specific political philosophy, she endorses broad movement-based politics in the spirit of Martin Luther King Jr. (including his frequently forgotten Poor People’s Campaign).

Alexander’s scholarship has predictably been questioned by people invested in the status quo, but it is rock solid. When looking at attempted “rebuttals”, be sure you’ve actually read her entire book (she anticipates many responses), and that you’re familiar with the “stock and flow” distinction.

Also note that Alexander does not explore in-depth the connection between the drug war and violence; other scholars have demonstrated that drug-related violence is the inevitable byproduct of aggressive prohibition politics. Johann Hari’s Chasing the Scream about the drug war, while not as rigorous as Alexander’s work, is an easy read and very complementary (see my review).

Finally, while The New Jim Crow is well-sourced, it uses statistics primarily to underscore its key points; for extensive charts and data, see sites like the Sentencing Project, Vera, the Drug Policy Alliance, and the Brennan Center.