Latest reviews

William Gibson’s 1984 novel Neuromancer is considered one of the greatest works of cyberpunk fiction. Hence my excitement when I began reading it, as a big fan of cyberpunk aesthetics and motifs myself. Even if you disregard the technobabble, which is a significant portion of the book, it still makes very little sense. The constant, vivid description of impossible surfaces does not seem like is meant to be understood literally, but as a metaphor for something else which eludes this reviewer. Most of the time reading the book, the readers will likely find themselves struggling to understand what exactly is happening under all that made-up jargon that mixes up 80’s futurism (which is fine) with authentic, unexplained original concepts and a pinch of redneck Americana parlance, which completely undermine the aesthetics and design that a cyberpunk enthusiast would expect. The inclusion of “Rastafarians” doesn’t help either.

Watching Blade Runner, Ghost in the Shell, Akira, or reading Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? will not prepare you for this monumental let-down. Avoid it.

I can’t imagine a rational, open-minded person reading this book and not coming away with the conclusion that drug policy almost everywhere in the world is in dire need of reform. Hari helps us see drug users as human beings, and addiction as a complex phenomenon that goes well beyond the chemistry of the drugs involved. I deeply admire the empathy and compassion that went into this book, alongside years of effort.

It’s not a perfect book by any measure. Like so many journalists and popularizers, Hari wants to get to the simple conclusions and quotable soundbites. In doing so, he sometimes oversimplifies science (when he tries to quantify the percentage of addiction that is caused by the drug itself) and history (when he reduces the cast of characters in the drug war to a few notable individuals, such as Harry Anslinger).

The structure of the book as a whole works, but at times both the formulaic narrative (e.g., opening many chapters with a “rule of three” set of characters) and the frequent section jumps can be a bit jarring. Recent technological developments (e.g., Silk Road) aren’t mentioned yet. The effect of free market capitalism on drugs (alcohol advertising, the many shenanigans of the tobacco industry, etc.) is hardly touched upon. And don’t expect to get much in the way of explanations of how different drugs work, or what the research says on drugs like LSD or MDMA — turn elsewhere for that.

None of this distracts from the core message, which is really about the role addiction plays in our society, and how we respond to it. The evidence, while at times made overly quotable, is presented fairly; the success stories of reform are real, and the cost of the drug war is not in dispute. What Hari does do exceptionally well is to tell stories, rather than drowning the reader in statistics (the stats are there, where pertinent, but never dominant). The net effect is that this book will hit you emotionally, if you allow it to.

4.5 stars, rounded up - because the cause for reform continues to warrant urgent attention from any thinking, compassionate human being, and this book makes that case very well. Let’s hope Hari is right that we truly are in the “last days” of this horrible hundred-year-war.

Common Dreams has been around since the late 1990s. It’s a non-profit news website that’s featured contributors like Noam Chomsky, Molly Ivins, Robert Reich, Howard Zinn, and other voices of the political left in the United States. It is funded exclusively by small donations from its readers, which means you’ll occasionally see Wikipedia-style fundraising banners among the content. Indeed, Common Dreams uses the Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License, the same license used by Wikipedia.

Typically, you’ll find opinions and analysis that are aligned with the Green Party and the far left in the US. The site’s relatively small budget means that some reader discretion to double-check sources is advised, and the quality of writing and editorial selection varies. At the same time, the site is relatively free of conspiracy theories and is a good source for alternative news especially on environmental issues and civil rights in the US.

The Common Dreams Commons is a surprisingly active forum (running the open source Discourse software), but unfortunately does not set itself apart from the comment sections of other news sites in meaningful ways.

Common Dreams rarely get major scoops, but it’s worth following them on Twitter (and perhaps making a donation once or twice a year) to get an additional perspective that unskews some of the selection biases of larger for-profit media.

Markhoshiki is a number puzzle game. It’s like sudoku, but you place number sequentially on the board. There are four quadrants of cells on the board and the goal is to fill all the cells. Numbers flow clock-wise direction among the quadrants. The board is filled with some numbers initially. The player need to fill the numbers in all the cells to complete the sequence.

The game is fun to play. It took a while for me get it and how to play it. There is a handy help and tutorial to the rescue. As we get more comfortable with easier levels, we can venture into bigger size boards and more difficultly levels.

There is notes functionality that allows one tentatively put multiple numbers in a cell. But, notes functionality needs an improvement. (I started using notes less and less, and it is more fun that way. I could not complete many boards in extreme level without notes, though.)

The game is available as a web app also. I find it is comfortable to play 5×5 boards on a bigger screens than on smaller smartphone screens.

The Quinta da Boa Vista (English: Estate with the Good View) is a beautiful park in Rio de Janeiro, one of the few green spaces in the North Zone. It’s a great place to take your family on holidays for a picnic, or maybe to visit the National Museum, former home of Brazil’s Imperial Family in the 19th century which now houses art, history and even dinosaur fossils!

All in all, it’s a fantastic option not only for city residents but also tourists. There is no fee to enter the park, which makes it even more appealing for visitors on a tight budget.

We love ordering Indian food at least about once a week, so we’ve been looking for a place that delivers to SE Portland and offers great value. So far, India Grill is the best we’ve found. Ordering via GrubHub, the minimum is $20 at a $7.50 delivery fee. You’ll find the usual staples: pakoras, samosas, palak paneer, various meat and veggie curries, etc., but no dosas. We’re both vegetarian, and there’s lots of good options here to choose from.

The food tastes authentic; it uses the right spices and is very rich & creamy. The paneer actually tastes like cheese (with other restaurants we’ve tried it’s often been completely bland). And delivery has been pretty fast and reliable so far. Great choice to try, and we’ll definitely check it out in person next time we’re in the area.

“Animation” has become almost synonymous with “fully computer-generated”, but Oregon-based Laika’s stop-motion films (Coraline, ParaNorman) are a notable exception. Kubo and the Two Strings is the studio’s latest effort, which seamlessly blends physical objects animated by hand with computer-generated backgrounds. The studio uses 3D printing to rapidly prototype characters, monsters, and set pieces.

This leads to amazing visuals that stand out, where the play of light and shadows and the texture of the world feel closer to our own reality. Indeed, watching the animators arrange and move the characters may remind you of special effects teams in the pre-CGI era assembling ridiculously detailed models and animatronic creatures.

But the best technique is nothing without a good story. Kubo takes place in a fantasy version of ancient Japan. It tells us about a small boy whose mother guards him against the evil forces in her own family. Eventually, Kubo must face these forces, with a magical monkey, a samurai beetle, and a paper knight by his side. Kubo himself can use origami magic to bring stacks of paper to life, which comes in handy along the way.

I suspect many associate the style and setting of Kubo with movies that are light on plot and fun, and heavy on art and poetry, and may avoid it for fear of a film that’s more demanding than rewarding. This isn’t the case here. Like Coraline and ParaNorman, Kubo packs lots of humor, emotion, and plot twists. It’s a moving story with a lovely ending, but it doesn’t resort to standard Pixar devices to pull your heartstrings.

Instead, we get a story that speaks beautifully about love and redemption, about loss and memory and community. One cannot deny the influence of Miyazaki (Spirited Away) and Studio Ghibli, which director Travis Knight has acknowledged. But this film stands on its own, and it deserves to be seen.

As a German who has now been living in the US for eight years, my perspective on racism in this country is colored by what I learned from an early age about my own country’s history: about the Nuremberg race laws, the Kristallnacht, the Warsaw Ghetto, the mass killings by Einsatzgruppen, and ultimately the Holocaust – the organized mass-murder of six million human beings.

As children, we would learn about these facts about our country not just through textbooks, but also through organized viewings of films like Schindler’s List, school exhibits, visits to museums, and even visits to the concentration camps themselves. At times, fatigue would set in: this was not something we had been involved in, or even our parents. Why must we keep talking about it?

But then, in the early 1990s, Germany experienced a wave of neo-nazi attacks on foreigners and asylum seekers. And it was then – I was 13, 14 years old – that I realized that there had in fact been a deep civic purpose in studying this history.

I moved to the US in the year Barack Obama was elected President, and the feeling that a very old divide was finally being healed was palpable. Americans could celebrate themselves as good people who had elected an African-American with the middle name “Hussein” and a last name that sounded like “Osama”, ignoring race and embracing a positive, optimistic message of “hope and change”.

The cancer of racism

But white voters did not vote for Barack Obama. 55% of them voted for John McCain. And we know about the ugly conspiracy theories around Barack Obama’s place of birth and religion, and various attempts to smear him as a dangerous radical who fraternizes with terrorists. This revealed another side of America, the ugliness that many thought we would be able to leave behind. The cancer of racism.

Ava Marie DuVernay is no stranger to fighting this cancer. In 2014, she directed Selma, a beautiful historical drama based on a pivotal moment in the struggle of African-Americans to have their say at the ballot box, a struggle which continues to this day.

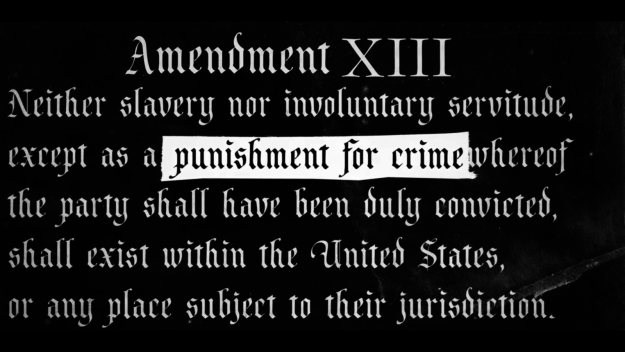

Her new documentary, 13th, is available on Netflix. The title refers to the 13th amendment to the US constitution which abolished slavery, but permitted forced labor in prisons.

13th calls this a loophole, and notes that it was quickly exploited to arrest freed slaves for “loitering” or “vagrancy” and then force them to work on rebuilding America after the Civil War. It chronicles the history of racism in the United States since then, including the FBI’s campaign to destroy efforts by African-Americans to build a social movement for equal rights. It then describes Richard Nixon’s “Law and Order” presidential campaign, and offers a recently surfaced quote by Nixon advisor John Ehrlichman which deserves being quoted here in its entirety:

“The Nixon campaign in 1968, and the Nixon White House after that, had two enemies: the antiwar left and black people. You understand what I’m saying? We knew we couldn’t make it illegal to be either against the war or black, but by getting the public to associate the hippies with marijuana and blacks with heroin, and then criminalizing both heavily, we could disrupt those communities. We could arrest their leaders, raid their homes, break up their meetings, and vilify them night after night on the evening news. Did we know we were lying about the drugs? Of course we did.”

Criminal injustice

13th goes on to describe the effects of disparate sentencing (e.g., with African-American crack cocaine users being sentenced far more harshly than white cocaine users), and the explosion of the US prison population under the “tough on crime” policies of Reagan, Bush and Clinton. It describes the rise of the prison industry, and the activities of the shady American Legislative Exchange Council in promoting “Stand Your Ground” laws and private prisons.

The film does not spend a lot of time on the “forced labor” aspect, explaining only briefly which industries rely on it. In general, aside from prison population numbers (including the horrifying racial divide of the prison population), this is a film that is more about politics and history than about statistics and data. It cannot entirely escape the gravity of the US presidential election, and it powerfully ties Trump’s racist campaign and the struggle of the Black Lives Matter movement back to images of hate and violence directed against African-Americans in the 1960s.

The documentary doesn’t have a strong authorial voice; instead it uses rap music with text overlays to create emotional breaks in the story. While it starts and ends strongly, it at times “loses the thread”, throwing too many facts at the viewer, “building awareness” at the cost of being less effective. Ultimately, however, its core message comes through very clearly: racism is a cancer that adapts to its environment, and to defeat it, we must understand this process of adaptation.

13th warns of a future after mass incarceration which The Daily Beast referred to as “Ankle Bracelet America”, where individual surveillance and enslavement of prisoners outside prisons could take the place of criminal justice reform, creating (again) merely the illusion of real progress.

At 100 minutes with many emotional scenes (tears started to well up in my eyes several times), this isn’t an easy documentary to watch. But if this election season is teaching us anything, it’s that the cancer of racism in the United States is alive and well. To defeat it, we must learn how it adapts and metastasizes. Ava Duvernay’s 13th is an important contribution to that understanding, and I do recommend it.

As this WaPo story explains, the Mini Museum was a childhood dream for Hans Fex, one which he pursued with undying ambition until crowdfunding made it possible to realize it. The idea is simple enough: create a portable doorway to wonder by encasing miniature exhibits ranging from bits of ancient meteorites over Ammonite fossils to parts of the Cray supercomputer.

Now in its second limited edition, it comes in at about $300 in the large version and $100 in the small one. That may seem like a hefty price tag, but if you’re looking for an awesome gift for the science nerd in your life (young or old), this is a pretty great find.

The attention to detail here is really quite stunning. For example, among the items encased in the beautiful block of Lucite are shipwrecked Spanish coins. But of course the coins would be too large, so instead the encased pieces themselves are shaped like coins! The tiny pieces of meteorites for the “asteroid belt” exhibit are similarly arranged to look like an asteroid belt.

Each item has a story, and the booklet that accompanies the museum provides a good starting point for Wikipedia searches and further exploration.

I can find nothing to criticize here – this is a product made with abundant love for curiosity, science and wonder. I highly recommend it.

Oliver Stone’s Snowden does not attempt to create a balanced picture of the NSA whistleblower – it treats him, straightforwardly, as a hero, a conservative patriot who finds himself forced to blow the whistle on the US government’s mass surveillance apparatus. This is a movie that takes a side. It does this explicitly by letting Snowden play himself briefly towards the end.

Based on all the facts I’ve seen, this treatment seems close to the truth and therefore doesn’t bother me – false balance, on the other hand, can distort the truth. The Economist, for example, writes in a critique of the film: “It is well documented that the real-life Mr Snowden declared his love for his Walther P22, his disgust with the vibrant, varied Muslim population of east London…”

What? Out of thousands of comments on messageboards and IRC over several years, you want to pick out the one set of throwaway comments most likely to offend the readership of the Economist to create a more “balanced” portrait of the man? The movie does portray Snowden as a conservative and a libertarian fan of Ayn Rand, and that seeems, at a high level, a reasonable summary.

As a movie, Snowden works well. Joseph Gordon-Levitt does a remarkable job portraying different sides of the character: Ed Snowden’s earnest search for a meaningful role in government, moments of pure whimsy with his girlfriend (played by Shailene Woodley), the many ethical challenges he encounters in his work, and the liberating moment when he walks out of an NSA facility in Hawaii with a stash of government documents. JGL is a joy to watch in this role.

To me, the weakest moments of the film were the interactions between Snowden and the fictional character Corbin O’Brien (played by Rhys Ifans and named after Winston Smith’s antagonist in Ninteen Eighty-Four). O’Brien is a cartoon villain, and even acts like one in a scene with a giant screen meant to evoke George Orwell. This would all be fine in a fictional tale about surveillance; here it distracts from the authenticity of the story.

On the substance, one important thing that Snowden gets right is that terrorism provides the necessary pretext for mass surveillance, but it is already used for many other purposes, including economic and political espionage and sabotage. And in a chilling moment, Snowden reminds us that this infrastructure creates the conditions for “turnkey tyranny” under an authoritarian presidency.

Snowden clocks in at 137 minutes and would have benefited from some more editing across the board (as cool as it is to have Nicolas Cage in the movie, it’s not clear that his character adds much to the overall arc, for example).

Overall, I recommend watching the film – it’s obviously not a documentary, but it does a good job explaining why Snowden did what he did, and why we should all be grateful for his revelations.