Reviews by Team: Interactive Fiction

Imagining worlds together

“And when they knew the Earth was doomed, they built a ship.” In one opening sentence, John Ayliff’s text-based browser game Seedship evokes stories of the journey to another world, of efforts to settle a new planet while avoiding the mistakes of the past.

1,000 colonists are all that is left of the human race, and they are asleep in hibernation chambers. You control a shipboard Artificial Intelligence that is meant to find a new home for humanity—a mission that will take thousands of years to fulfill.

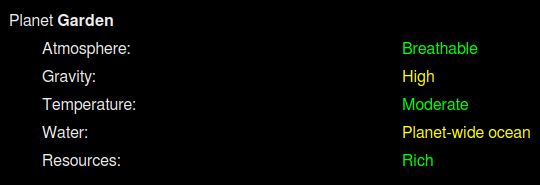

You travel from one planetary system to the next, and you use scanners and surface probes to determine the suitability of candidate planets for human settlement. Does the planet have a breathable atmosphere, Earth-like gravity, tolerable temperatures, sufficient water and other resources?

Planets may hold other surprises for the colonists, from poisonous plants to high-tech ruins of previous civilizations. Based on all available information, you can decide to found a colony, or to keep searching.

Risks and Rewards

Every part of the ship, including the hibernation chambers, may be damaged during interstellar travel. On the other hand, you also have opportunities to upgrade your ship, which may improve your odds of finding a suitable home.

Ultimately, the success of your mission comes down largely to luck. You may find a lush paradise planet early, or encounter one toxic wasteland after another.

Seedship features no graphics, but its text-based interface, such as the scan results shown here, manages to convey a lot with few words. (Credit: John Ayliff. Fair use.)

What makes the game so enjoyable is the quality of the storytelling. Ayliff has stocked Seedship with many random events, from encounters with alien spaceships to the discovery of a brutal dictator among the sleeping colonists. Your choices (eject the dictator or let him sleep?) almost always have consequences, but those are often unpredictable.

When you decide that you’ve found the perfect (or at least adequate) new home for humanity, Seedship tells you about the fate of the colony. Did humanity maintain its previous level of technological achievement, or regress to a medieval level? Is your new society an enlightened utopia, or a tyrannical police state?

A single run can take only a few minutes, but you may find yourself playing Seedship for well over an hour to discover the different possible futures for humanity. If you enjoy sci-fi stories, I highly recommend giving it a try.

The world as we know it has ended long ago, and the ruins of San Francisco are crawling with orcs and goblins. Your are a novice necromancer, in pursuit of your brother, who has abandoned you and your family in search of fame and fortune. Perhaps you will find him somewhere in the Transamerica Pyramid, one of the few tall buildings that are still standing.

Knights of San Francisco is a choice-based adventure game for Android and iOS made by a single developer, Filip Hracek, and a single illustrator, Alec Webb. It is mostly text-based, and the gameplay is somewhat reminiscent of Choice of Games titles, but Knights also severs to showcase the game’s own engine, Egamebook.

You move through the game’s world by selecting destinations on a map. As you do so, you encounter allies, enemies, and items that may help you on your quest. During turn-based combat, you control only your own actions (your allies attack independently). You are given a surprisingly large set of choices, from feinting, to casting a spell, to kicking a weapon out of the way.

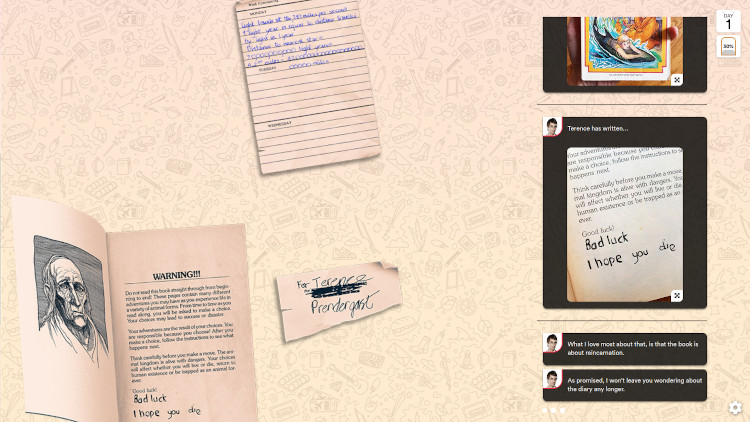

The game is mostly text-based, but the illustrations by Alec Webb help to establish the setting. (Credit: Raindead Games / Alec Webb. Fair use.)

After each choice, a dice roll determines success or failure; if you fail, you can drain your stamina or sanity points to re-roll. The game generates text that describes the result of each combatant’s actions.

There are no hitpoints or levels, and death can come quickly. Still, thanks to your allies, the necromancy skill, restorative items, and the re-roll option, most battles will not present much of a challenge. Just in case, the game lets you rewind bad decisions (I only had to do so once).

The story is told in short paragraphs, much of it through dialog with friendly characters which you can skip if you prefer to focus on combat. The writing is solid, and you do get to make a choices that will shape the story and its ending.

If you’re looking for a game that will give you hours of replay value, this isn’t it—a playthrough takes about 60-90 minutes, and there’s not much that changes on a second run. But it’s immersive, novel, and fun, and only costs $3. Whether or not you pick this one up, Raindead Games is worth keeping an eye on.

The Boy in the Book is a web-based full-motion video game; the website describes it as ”an interactive true story in 10 chapters”. It is free without any strings attached, and has also been published in book form and performed as a live show.

The game/documentary is premised on the random discovery of pages from an old diary in a stack of Choose Your Own Adventure books bought on eBay. In almost stenographic shorthand, the diary pages record the author’s experiences with bullying, with their attempts to overcome extreme shyness, and even suicidal thoughts.

The notes suggest that the diary’s author, a boy named Terence Prendergast, was born in 1975. Is he alive, and if so, what happened to him since he wrote the diary?

Choices in the chatroom

The buyer of the books, a Welsh writer and performer named Nathan Penlington, sets out to discover and document the story of the “boy in the book” together with his friends Fernando, Sam, Nick—and with you, the player.

You interact with Nathan & friends through an instant message chatroom in which the group discusses what to do: which leads to pursue to locate the author of the diary, which detours to take along the way, and whether to persist in what increasingly seems like a futile quest.

As the player, you are presented with dialog options throughout the chat, which sometimes represent important forks in the road. Depending on your choices, different responses, videos and images appear in the chatroom. They are grounded in the same reality (e.g., the same interviews), but put the focus on different narrative paths.

The events of the game play out in a chatroom with Nathan and his friends. Like in a “Choose Your Own Adventure” book, you get to make choices about how their effort to document the story of “the boy in the book” unfolds. (Credit: https://www.theboyinthebook.co.uk/. Fair use.)

Abort, abort, abort?

You can rewind your choices and take as many different paths as you like, and the game auto-saves in your browser (if you don’t play it in private browsing mode).

To underscore that these choices are meaningful, Nathan asks you in the first chapter whether he should pursue his obsession with the diary at all. If you tell him not to, the story comes to a quick end and the credits roll.

Nathan’s question is a fair one. The ethics of the whole undertaking can sometimes feel uncomfortable, since the found diary pages are presented as the writings of a private individual. As you play through the story, it becomes clear that everyone is appearing on screen willingly.

The Verdict

While the story feels a bit padded out in the way many documentaries are, I still found it was ultimately beautifully done and well worth my time. I watched two of the main endings and was moved by both of them. In total, I spent about two hours with The Boy in the Book.

The game features gorgeous illustrations and a fitting soundtrack. Overall, I found that the web-based format worked surprisingly well, with two exceptions: 1) The rewind feature didn’t always work for me (text was sometimes repeated or did not appear until I reloaded), 2) the game’s music kept playing even during videos which had their own music in them, which was a bit distracting.

The individual chapters are quite short. I would recommend giving the first one a try. If you find Nathan in particular offputting at all, you’re not going to enjoy The Boy in the Book—he’s on screen a lot. But if you like his style, and if you share at least some appreciation for Choose Your Own Adventure books, you’re likely to have a good time.

So, what is your robot going to look like? Will it be a box with eyes on wheels, a flying furry puppet, a spider-robot with 360-degree vision? Make your selection and be presented with—another screen of text.

Choice of Robots is a game by Choice of Games, a company that should not exist. At least not if gaming followed the conventional history in which video game genres are forged in the fire of one generation of computing hardware, only to be wiped out in the avalanche of the next. Text adventures? They have gone the way of the dodo and the cathode-ray tube, surely.

Not quite. In 2009, Choice of Games released “Choice of the Dragon”, a text-based adventure game that became a smash success on mobile devices. Since then, they have released more than 100 titles under the “Choice of” label. The company has also made its game engine available under a license that permits noncommercial use, and they publish an endless flow of user-created titles.

It’s hard to explain the appeal of “Choice of” games if you haven’t played one. So go ahead, and try the damn dragon game in your browser. While the games share similarities with “Choose Your Own Adventure” gamebooks (“to attack the dragon, turn to page 69”), they offer a much larger number of choices, track internal variables, and do other things that computers can and books can’t. One thing they don’t do: trying to parse text input (“GET LAMP”). If you’ve ever played an old school text adventure, the parser is the one thing likely to drive you bonkers, because typing the exact words the computer expects can be a stochastic nightmare.

Just a few paragraphs of text, next choice. A bit more text, next choice. The formula works beautifully to get you to read a book without realizing it. (Credit: Choice of Games / Kevin Gold. Fair use.)

Robots then! Choice of Robots author Kevin Gold knows 01 thing or 10 about them. An Assistant Teaching Professor at Northeastern University, he “received his PhD from Yale University in 2008 for research on how robots could learn the meanings of pronouns and other abstract words from examples.” Choice of Robots isn’t about pronouns, though—it’s more about fulfilling that fantasy of “conquering Alaska with your robot army” that you’ve always had. OK, you also do get to pick your robot’s pronouns.

You start the game designing your robot and then walk down your chosen path, to achieve your destiny as a reclusive robot tinkerer or a power-mad corporate overlady. Yes, those are the only two options. Just kiddding.

The game beautifully adapts to your decisions. If you want your Alaska fantasy, that’s what you’ll get (hey, no judgment). If you want a love story, that’s what you’ll get. If you want a tale in which hyperintelligent robots become good-natured shepherds of their obsolete human builders, that’s probably also what you’ll get, but ask your robot supervisor.

Aside from the romantic options being fairly limited—this ain’t a robot dating sim—none of these paths feel underdeveloped. Gold’s writing draws upon the real world (let your professor introduce you to the military-industrial complex), on myths and legends (dress up as Hephaestus at a party), on literary references (quote The Tempest at a funeral), and much more. It does so while staying lighthearted and unpretentious, even as Gold’s PhD ever looms in the game’s byline.

Choice of Robots may make you think about what the future holds, but most of the philosophical ground it visits is well-traveled. It’s in the nature of the game to not be morally prescriptive. In other words, you can be clearly quite evil, if that’s how you want to play it. As an interactive story, it’s a masterclass that’s sure to keep you entertained for a few hours. To send your flying muppet into the world, it’s well worth the six bucks.