Reviews by Eloquence

What is integrity? We expect governments to act in the public interest, to root out corruption, to uphold the rule of law. We expect businesses to follow the law, to pay their fair share of taxes, to not abuse their power. We expect nonprofits to act in accordance with their mission, to avoid wastefulness, to be transparent.

The Center for Public Integrity (CPI) is an investigative journalism nonprofit based in Washington, D.C. that’s dedicated to documenting abuses of power in these and other institutions. It defines itself as nonpartisan and has indeed conducted many investigations across the political spectrum.

Although its name and location might suggest a “think tank” type organization, CPI is fully focused on producing journalism – often published in partnership with other news outlets.

Funding and Executive Compensation

Founded in 1989, CPI had revenue of about $9M in 2015. According to its Annual Report, almost all of its revenue comes from grants and donations. Most of its support comes from large gifts and grants (many from the typical foundations that fund journalistic work); in 2016, CPI received $210K in donations smaller than $250.

As of November 2016, CPI’s CEO is John Dunbar, an investigative journalist and CPI veteran. Because of the recency of his appointment, compensation information is not available yet; his predecessor received $301K from the Center in 2015, which is squarely in the middle between ProPublica and the Center for Investigative Reporting in terms of executive compensation.

CPI states: “We maintain a strict firewall between funding and our editorial content.” It publishes its editorial standards which include a requirement for full disclosure of conflicts of interest, and a commitment to avoid such conflicts where possible.

Reporting

Compared with ProPublica and CIR, CPI has a stronger focus on institutions, both public and private. With regard to government, since 2001, no news organization other than the New York Times has filed more Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) lawsuits than CPI, according to a report by the FOIA project. These types of lawsuits are necessary to challenge government over-classification of materials.

The recent CPI report regarding what amounts to a massive gift to the insurance industry by the taxpayer-funded Medicare program is an example of an investigation that was made possible through a FOIA lawsuit.

CPI investigates both Republicans and Democrats, and I was not able to detect a bias towards either group. The report on ambassador postings for donors to the Obama campaign is a good example of data-driven journalism targeting the Obama administration, while CPI also reported in detail on the perks and access offered to big donors to Donald Trump’s inauguration.

Businesses are far from immune from CPI’s investigations. In 2014, CPI received a Pulitzer prize for an investigation which revealed “how doctors and lawyers working at the behest of the coal industry helped defeat benefit claims of coal miners who were sick and dying of black lung disease.”

After the 2008 financial crisis, CPI published some of the most in-depth reporting on the links between banks that received bailout money and the subprime lenders that caused the crisis. Through the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, which it launched in 1997 and which it houses, CPI has helped bring about the most important investigations into tax havens and offshore banking in recent history, including the Panama Papers investigation.

CPI publishes a running log of all corrections.

Website, Licensing

CPI’s website is easy to read and offers section views for its primary ongoing investigative domains (e.g., politics, business, environment). The content is not sensationalized, and as with other investigative sites, you’re probably more likely to read an investigation of interest to you through a social media or RSS feed than by going directly to the site. Content is generally in text form, and the site looks reasonable on mobile devices.

Donation appeals are visible but not annoying. Stories use Facebook comments as a discussion system; commenting guidelines are buried in the terms of use, and I did not see evidence of moderation (which doesn’t mean it doesn’t happen). Content is under conventional copyright and sometimes cross-published to other news media. In general, CPI is a cathedral-style journalistic organization with limited community engagement.

The Verdict

I would recommend CPI without reservations for your RSS or social media feed. The institutional focus distinguishes it from ProPublica and CIR, and this focus has led it to dig into some of the largest scale, most systemic abuses in areas such as the financial services industry. Its incubation of the International Committee for Investigative Journalists was a brilliant move in that regard, since many of the most complex tax avoidance schemes are international in nature. This makes CPI/ICIJ truly indispensable.

It’s not surprising that an organization with “Integrity” in the name does a good job with organizational transparency. Financial documents and annual reports are easy to find, and the donor information is comprehensive. In spite of all these editorial and operational strengths, CPI still has a relatively small online presence – 74K followers on Twitter, 83K on Facebook.

Doing more to engage (and involve!) readers through these channels without compromising on its strengths may help build a larger audience, which in turn may translate to more bottom-up funding. Given that CPI, ProPublica and CIR are all nonpartisan, we might also hope for more collaboration between them in future.

Because of its high impact business and government investigations, I give CPI 4.5 out of 5 stars, rounded up. It is now also in the Twitter list of quality nonprofit media.

Bozeman Science is one of those YouTube channels you probably have never heard of that’s managed to become very, very popular. As of this writing, it boasts more than 500,000 subscribers, and its most popular videos (e.g., “A Tour of the Cell”). have been viewed millions of times. It is run by Paul Andersen, a high school teacher and education consultant from Bozeman, Montana (a small US city known as the location of the first contact between humans and Vulcans, at least if you watch Star Trek).

Many of the videos are on subjects relevant to biology: photosynthesis, cellular respiration, gene regulation, gene editing with CRISPR, and so on. Andersen also explores topics in chemistry, physics, statistics, and – especially recently – education itself. For example, one video introduces the educational practice of modeling instruction, where students are asked to develop their own models to explain how a scientific phenomenon works, which they then reason about with other students and the teacher.

These videos do require focused attention and a willingness to research the occasional bit of jargon. Andersen moves relatively quickly through his content, so although a video might only be 5 minutes long, you might have to watch it 2-3 times and consult some additional materials to “get it”. That’s not really frustrating, since Andersen has the calm and confident voice of a good teacher and is easy to listen to.

The videos use plenty of illustrations, and Andersen takes pains to overlay textual corrections to note errors in the original recording. If you’re going to check out one of his videos, I would make it the introduction to CRISPR gene editing, since it remains a very relevant topic and is also a good example of his teaching style.

Andersen relies on donations to support his work, but he does not appear to have plans to turn it into a larger franchise like Khan Academy. As it is, if you’re into science (or prepping for exams), I recommend subscribing to the channel and checking in from time to time for topics that may interest you.

In 1977, long before the Internet gave new life to nonprofit media, Bay Area journalists David Weir, Dan Noyes, and Lowell Bergman founded the Center for Investigative Reporting (CIR) in Oakland, CA. The nonprofit organization’s mission is to create investigative journalism that “sparks action, improve lives and protects our democracy”.

It did so initially by working primarily with other news outlets. A first major collaboration was a 1978 exposé by Kate Coleman and Paul Avery regarding the Black Panther Party and its involvement in organized crime, including murder. Since then, CIR has produced deep investigations about all sectors of society, for example:

-

“Reasonable Doubt” (with CNN), a 2007 investigation into poor quality controls at forensic crime labs

-

“Dirty Business”, a 2009 documentary about the myth of clean coal

-

“The God Loophole”, a 2016 investigation of abuse at religious daycare facilities

CIR has received numerous journalism awards, including a Peabody, and the organization was a finalist for a Pulitzer prize in 2012 for its investigation of earthquake safety of California schools.

This focus on wrongdoing in any part of society makes it similar to the younger, NYC-based ProPublica, and indeed, in many ways, CIR is its West Coast counterpart. The two organizations had nearly the exact same amount of revenue in 2014 ($10,324,242 vs. $10,324,275) and draw funding from similar sources, primarily foundations and major gifts.

Unlike ProPublica, CIR does not provide a breakdown of its revenue by source, but it does provide a list of supporters, which includes Gates, Carnegie, Rockefeller, Open Society Foundations, Hewlett, MacArthur, Knight, and many of the other big names in philanthropy. An editorial independence policy is meant to make it clear that such support does not influence reporting.

One notable difference between the two is executive compensation. CIR pays its Executive Director a total of $232K, while ProPublica’s highest compensated “co-executive” makes $429K. CIR does not publish an Annual Report, but it does use an open source impact measuring tool to produce whitepapers documenting the real world effects of some of its most notable investigations.

As an older organization, CIR had to transform itself for the Internet. It now publishes its investigations on Reveal, which features in-depth reporting, podcast episodes, videos, and occasional data journalism. The grouping of investigations (e.g., “Hidden abuses under the watchtower” for its Jehovah’s Witnesses investigation) makes the current focus areas reasonably clear.

While it utilizes text, audio and video for its reporting, in many other respects, Reveal is very old school. There is no commenting system, content is under conventional copyright (as opposed to a Creative Commons License), and the heading “Get involved” only leads to an ask for donations.

The Verdict

As with ProPublica, the universal search for abuse (and the heavy reliance on conventional funding) can make it harder to address system-level issues such as inequality, climate change, electoral injustice, or mass incarceration. Efforts like CIR’s are therefore no substitute for values-driven journalism that provides consistent emphasis on systemic injustice.

On the other hand, the Center’s investigations into all sectors of society do help people to learn about (and act on) abuse and wrongdoing within their communities. On that basis, I recommend following Reveal, and the feed is now part of the Twitter list of quality nonprofit media. 4 out of 5 stars.

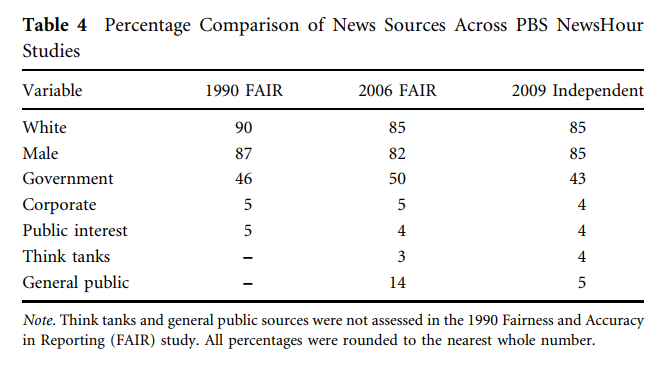

Journalists like David Brooks and Mark Shields provide background on the news, reflecting a general bias of sourcing (85% male, 85% white) that has been consistently documented.

NewsHour is the flagship public television news program in the United States, distributed by PBS and produced as a collaboration between key member stations. As with all public broadcasting in the US, it relies on a mix of funding that includes government support, corporate underwriting, foundations, major donors, and small donors. PBS programs are subject to funding standards, and an ombudsman serves as a verbose internal critic.

Executive compensation at some member stations reaches excessive levels by nonprofit standards – nearly $600K for WNET CEO Neal Shapiro (WNET co-produces NewsHour). This is a reflection of competition for talent with for-profit media (Shapiro was previously the President of NBC) and the large organizational size, but still merits scrutiny as it can reinforce leadership trading within a media oligopoly as opposed to the development of a unique nonprofit media leadership path.

NewsHour made its debut as a nightly news program in 1983. It features headlines, interviews, and some in-depth reporting. Episodes can be streamed online, and segments of the program are routinely transcribed. Probably the biggest difference with for-profit news programs is tone, not content. The program projects a sense of respectful, calm, civil engagement with the issues of the day. That’s no small thing in an era where networks like CNN employ extreme partisans just to shout at each other. Of course, it can also contribute to normalization of extremes.

As far as content is concerned, NewsHour does generally take a longer, more global view than many other news programs. It routinely features topics from US history, developments in other cultures, and so on. The commitment to balance that’s part of the public broadcasting mandate typically translates to having a center-left and a center-right guest on the show for purposes of analysis (such as the Brooks and Corn / Shields and Brooks programs).

Studies both by progressive media criticism organization FAIR and by independent researchers have consistently shown that the sources NewsHour consults for expertise and interviews are 85% male, 85% white (the US is about 72% white), and about 45% government. Public interest sources, think tanks, and corporate sources are each sourced about 4-5% of the time.

That means organizations that are deeply familiar with topics like the drug war, voter suppression, the arms trade, etc., are rarely put on the air to talk about them. In its selection of core stories of the day, NewsHour also largely mirrors the choices of other news programs. There are exceptions, such its recent in-depth feature on the under-reported United States prison strikes, which is also notable in being singular.

The program exists in the larger context of public broadcasting in the US, which is frequently the target of efforts to either politicize or defund it. While government funding has its perils, the reliance on major donors and corporate underwriters also comes at a cost. Most significantly, Jane Meyer of the New Yorker exposed in 2013 how PBS member stations got cold feet about programs putting the spotlight on a major donor and trustee, David Koch of the infamous Koch Brothers.

Given this combined political and corporate influence, a program like NewsHour is likely to stay firmly within the Overton window in its reporting: views that are “too radical” either on the left or on the right will rarely be aired. But of course the window isn’t fixed – it remains to be seen how NewsHour will deal with the normalization of hate, and with politics under President Donald Trump.

The Verdict

For the time being, I still recommend NewsHour with reservations, since it at least leans towards public interest reporting rather than pure ratings-driven entertainment. It is a good bellwether of elite opinion, and provides more nuanced and careful analysis than any other centrist US news program I’ve seen.

3.5 out of 5 stars, rounded up. If you follow our Twitter list of quality nonprofit media, you will get updates from NewsHour alongside more political and adversarial sources like Mother Jones, The Intercept, and Democracy Now!, as well as the academic perspectives from The Conversation.

Ian McEwan is a giant of English literature, who is known for intricate, detail-obsessed storytelling (Atonement), but he is also a master of small stories. His latest novel is a short murder mystery told from the perspective of a late-stage fetus who has picked up quite a lot about the outer world by listening to podcasts and conversations. His mother Trudy, it turns out, is plotting an awful scheme against her husband John. Her partner in crime is her lover, her husband’s banal and obnoxious brother Claude.

The novel does not attempt to give any plausibility to our protagonist’s observations and reflections, which makes this a less gimmicky plot device than it otherwise could be. It is simply something the reader accepts. But at times our fetal narrator’s musings on subjects ranging from Islam to identity politics are too indistinguishable from McEwan’s own Guardian editorials. Don’t get me wrong – McEwan’s a smart guy, but this stuff feels out of place in an otherwise engaging story.

It’s a short novel that keeps your attention, not because of especially surprising plot twists and clues, but because the near-helplessness of our narrator adds a layer of intimate horror to the proceedings. Nutshell is not McEwan’s best work, but still worth the read. 3.5 stars, rounded up.

Moana tells the story of a girl of the same name who lives in a small village on the (fictional) island of Motunui. She’s the daughter of the village chief and set to lead her tribe, but she feels an inner calling to the ocean, which is off limits for the islanders.

The island, it turns out, is dying, and in order to restore it to life, Moana has to flout the ocean prohibition and go on a quest to return the heart to the island goddess of Te Fiti, with the help of the guy who stole it in the first place: the demigod Māui (loosely inspired by the mythological figure and voiced by Dwayne Johnson). Māui turns out to be a bit of a jerk, making the quest that much more difficult.

The CGI visuals are gorgeous, and teenage Hawaiian actor Auli’i Cravalho does a great job with Moana’s character, as does Dwayne Johnson with Māui. The quest is in parts predictable Disney formula and can feel a bit “on rails” for that reason, but the songs make up for that – including a fantastic villain song performed by Flight of the Conchords singer Jemaine Clement, and a remarkably good performance by Dwayne Johnson. They’re on YouTube, and if you don’t plan to check out the movie, you may want to at least listen to some of its standout songs (and then change your mind):

- You’re Welcome is the song performed by Johnson, which occurs shortly after his first encounter with Moana. The video shows the full scene and gives you an idea of some of the humor of the movie as well.

- Shiny is the aforementioned villain performance by Jemaine Clement, which is audio-only. Clement voices the gigantic coconut crab Tamatoa, pictured above.

- How Far I’ll Go and I Am Moana are more typical Disney fare, performed beautifully by Auli’i Cravalho. Mild spoilers in the second song.

I would give the movie 4 stars, but the music pushes it up to 4.5, rounded up. Recommended!

“The world deserves access to its greatest minds”, the slideshow begins, showing images of war zones. “Now more than ever the world needs access to reliable information.” The video is a fundraising ad for Project Syndicate, a nonprofit based in the Czech Republic.

The location reflects the organization’s original purpose. Project Syndicate was started in 1995 to help syndicate the views from “leaders and thinkers” from Western and Western-aligned countries to Eastern European newspapers. Today, it explains its model as follows:

News organizations in developed countries provide financial contributions for the rights to Project Syndicate commentaries, which enables us to offer these rights for free, or at subsidized rates, to newspapers and other media in the developing world.

While its tax returns are not publicly viewable, Project Syndicate’s CEO assured me that “it is registered as a public benefit corporation, 501c3 equivalent, in the Czech Republic. As such we register audited financials, board minutes, annual reports, etc every year with the appropriate Czech courts as required by Czech law.” He broke down the revenue composition of the organization as 60% subscriptions, 37% foundations, and 3% donations.

The website lists the Gates Foundation, the European Climate Foundation, and the UAE-based Al Maktoum Foundation as funders. That list is incomplete and may only reflect recent funding; George Soros’ Open Society Foundations, for example, gave $350,000 in 2014.

PS columns are translated by PS into multiple languages, and into many more by the participating newspapers. Each column includes a small speaker bio, but not a disclosure statement like the ones found in The Conversation (which I reviewed here).

Indeed, even funders themselves use PS to get their views out to newspapers around the world. This includes many columns by George Soros and by Bill Gates, two by Melinda Gates, and four by Mohammed bin Rashid al Maktoum. Each story includes an author bio, but does not disclose these funding connections.

Beyond its funders, the “greatest minds” whose opinions Project Syndicate spreads around the world include former and current world leaders, experts in academia, Nobel Prize Winners, and for whatever reason, Bjørn Lomborg. Lomborg, whose Ph.D. is in political science, has turned being a contrarian on environmental issues into a career, and his policy work (which many experts have described as scientifically dishonest) tends to be used by conservatives to justify luke-warmism: watered down approaches to solving environmental issues.

Columnists from politics include former UK Prime Ministers Gordon Brown and Tony Blair, former UN Secretary General Kofi Annan, former German foreign minister Joschka Fischer, and former US national security advisor Zbigniew Brzezinski.

Some of these folks are life-long public servants, others (like Blair and Fischer) have turned their post-politics careers towards more lucrative objectives. Blair in particular has been busy: consulting for the financial services industry, advising dictators through Tony Blair Associates, making a secret deal with a South Korean oil firm. None of these connections are disclosed in his PS bio, which focuses solely on Blair’s work through NGOs and academia:

Tony Blair was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1997 to 2007. Since leaving office, he has founded the Africa Governance Initiative, the Tony Blair Faith Foundation, and the Faith and Globalization Initiative.

This shows why disclosure statements are important.

By uncritically publishing views by Blair, Gates, Fischer, Brzezinski and other members of political and economic elites, PS implicitly will be less likely to air voices that are highly critical of them. This is not a publication that will give much credence to voices that allege that Henry Kissinger was a war criminal, a claim that even center-left Vox had to agree with.

Nor is it likely to criticize Brzezinski’s own record promoting Operation Cyclone, the massive, multi billion dollar program to arm Islamic extremists in Afghanistan as fighters against the Soviet Union, a program now widely regarded as exemplifying the blowback phenomenon where former allies turn against the state actor sponsoring them.

Indeed, as I write this, Project Syndicate is busy defending Saudi Arabia’s war in Yemen, with an editorial by Ali Al Shihabi, the “executive director of the Arabia Foundation, a new think tank that will focus on the geopolitics of the Arabian Peninsula”. Al Shihabi has calmly reassuring words for those disturbed by attacks such as the bombing of a funeral ceremony which led to 140 deaths. Totaling up the human cost of the war so far, he concludes: “For an air campaign waged for nearly two years against an unconventional army, this figure is not particularly high.”

That is not to say that Project Syndicate is a right-wing site. Far from it, its columns tend to occupy the center-left to center-right, to borrow a phrase from Hillary Clinton, and that’s following a more international definition of “centrism” than the right-leaning US version.

For example, PS created a special focus section on Donald Trump called “Trump: An American Horror Story”, and the site frequently reports on environmental issues and the international efforts to combat climate change. Here, too, it tends to follow more of a Hillary Clinton vision than a Bernie Sanders one, promoting fracking through several stories including, of course, one by Lomborg, who predictably calls it “this decade’s best green-energy option”.

In fairness, the credentialist centrism that defines Project Syndicate does leave room for a lot of sensible voices, including leaders of various NGOs and generally reasonable politicians arguing for peace, democracy, and apple pie. It has even given plenty of space to prolific progressive firebrand Yanis Varoufakis. But Jeffrey Sachs, who’s stuck with the project the longest as its first monthly columnist, is perhaps the best example of this benevolent form of punditry, the elite-friendly “how about we try this crazy thing” mentality that actually sometimes leads to positive agendas being implemented.

Project Syndicate content is licensed under conventional copyright – the newspaper subscriber model depends on at least some subscribers paying for the content. That said, the content is available online, sometimes in abbreviated form that requires logging in. There’s a small discussion section below each story, which usually receives a small to moderate amount of activity. There is no prominently noted way to submit corrections for any story.

The Verdict

Although non-profit, Project Syndicate is effectively mainly funded by for-profit media. It amplifies the perspective of elite voices across all sectors of society, while concealing conflicts of interest. The lack of obvious disclosure even regarding writers whose organizations are funders of the project, and the use of PR blurbs like Tony Blair’s, is especially iffy.

The bias towards credentialism is likely good for continuing to attract foundation funding and subscribers, but it doesn’t in fact engender a diverse set of perspectives. The Conversation, previously reviewed here, is a more inclusive alternative, in spite of its own selective focus on voices within academia.

Until Project Syndicate addresses some of its transparency deficits and manages to pivot towards a broader definition of “the greatest minds” with less emphasis on credentialism and increased focus on marginalized and underrepresented voices, I cannot recommend it as a source of analysis.

Nevertheless, I personally do follow Project Syndicate on Twitter to get a window into what views are being promoted by elites around the world, but it’s especially important to read it critically and conduct one’s own investigations of an author’s motivations and opposing viewpoints. Three out of five stars.

Partially inspired by the real-life case of Efraim Diveroli (played by Jonah Hill) and David Packouz (played by Miles Teller), War Dogs tells the story of two kids who were best friends in high school and reunite to build a shady company selling weapons of questionable origin to the United States government. The story is told from the perspective of the naive Packouz, who throws his lot in with Diveroli in hopes of becoming a good provider for his family, but gets in over his head almost immediately.

The film portrays Diveroli as a grotesque sociopath, and Jonah Hill has fun with the role, which doesn’t necessarily mean the audience does: watching a person behave as obnoxiously as possible gets old pretty quickly. In contrast, Miles Teller’s Packouz is simply boring, a “babe in the woods” character whose relationship is strained by the secrecy and lies surrounding his work.

The movie is at its best when it focuses on the parts of the story that are in fact based on the real world case: the open contracting process for arms sales, the growth of the Diveroli/Packouz business into a company that manages to land one of the biggest Pentagon contracts, the process of acquiring and re-selling arms of dubious provenance.

The arms business is one of the dirtiest in the world, and it deserves fiction and documentaries that uncover the link between the war profiteers and the untold harm their work inflicts on people they will never meet. In contrast, War Dogs is merely the story of a couple of hustlers whose actions are portrayed largely divorced from any real world consequences. The story unfolds fairly predictably and leaves us with little payoff.

Still, thanks to reasonable performances by Teller and Hill, and a fine cameo by Bradley Cooper, War Dogs is by no means a terrible movie – a reasonable choice for a boring evening or a long flight.

The Conversation may well be the most remarkable news site you’ve never heard of. After a start in Australia in 2010, the site has since added five editions: UK, the US, Africa, France, and a Global edition. The premise is simple enough: academics, researchers, and PhD students write news backgrounders, special reports, and explainers for complex topics, targeting a general audience. Readers are encouraged to engage in discussion with clearly stated and enforced community standards – and authors frequently participate in those conversations, as well.

The whole operation is fully non-profit, with funding that comes primarily from a large array of foundations and participating academic institutions. The most recent available tax return for the US edition, which is only 2 years old, notes about $2.3M in annual revenue, but The Conversation Media Group in Australia from which it spun off is a separate entity.

With a network of more than 36,000 writers, the scale of this project is staggering. These authors write in partnership with professional journalists who are part of the Conversation team. All content is under the Creative Commons Attribution/No-Derivatives License, which allows free republication without modifications, including commercial re-use. Because many sites do pick up their content, The Conversation’s reach extends well beyond the 3.7 million monthly users that go to the site directly.

The website runs on a custom content management system which is proprietary and likely to remain so. It is is quite well-designed: pages load fast, the multi-column layout is easy on the eye, the navigation makes sense, and it’s mobile-friendly. The commenting system is one of their own creation which, as of this writing, lacks functionality to edit one’s own comments but is otherwise easy to use.

Each edition has its own Twitter/Facebook/RSS feeds, so in order to get a mix of global and US posts, for example, you can just subscribe to both feeds.

So, what’s the content like? If you’re familiar with Vox.com, think of The Conversation as a less sensationalist version that is more careful with the facts while serving up more diverse views from around the world. Alongside lots of mundane stuff (the US frontpage article right now is “How making fun weekend plans can actually ruin your weekend”), that includes radical perspectives from time to time when they can be found in academia, such as articles by Greek academic and progressive firebrand Yanis Varoufakis.

And it also includes charming articles like How majority voting betrayed voters again in 2016, where a French mathematician advocates that the US should immediately adopt a voting method for presidential elections called “majority judgment” he and a colleague have devised. (The argument is interesting enough, but without grounding in any kind of political reality it is indeed a purely academic one.)

Consistent with standards in academic publishing, authors must disclose conflicts of interest and “relevant affiliations”, making it harder for the site to act as a conduit for advocacy by special interests.

All articles I’ve read meet a certain minimum bar of quality (they make an effort to engage the reader, they’re accurate and clear), but the ceiling varies considerably. In quite a few cases, you’d be better off heading over to Wikipedia to understand a subject, not because the backgrounder by The Conversation is wrong, but because it just consists of a few links and some fairly banal observations. Still, the site is (in my view) vastly preferable to commercial offerings like Vox because it publishes a truly diverse and increasingly global community of authors.

The Verdict

The Conversation is unique, and the site’s founders deserve credit for realizing a bold vision of a non-profit platform that helps us engage in smarter conversations with each other about the world we live in. Whatever your political views, I suggest adding one or more of their feeds to your news mix to sample their content.

If I could pick one area for the site to improve in, it would be to focus more on truly excellent journalism at the expense of sheer volume. Beyond that, a stronger commitment to open source values (opening up the platform, engaging the community in governance issues, using a more permissive license for the content) would be lovely to see. 4 out of 5 stars.

In 2008, journalist and author Bill Bishop co-authored The Big Sort: Why the Clustering of Like-Minded America is Tearing Us Apart. It examines how communities across the US are becoming more politically one-sided. This isn’t just a Kentucky vs. California thing – within these states, you’ll find increasingly sharp political divisions. Part of the reason is that people like to live with others who think like them: they “sort” into communities that reflect their values.

In this climate of polarization, it can become easy to fall into stereotypes, and to lose sight of common concerns that all communities share: jobs, access to health care, working infrastructure, clean water and clean air, and so on. Bishop is also a journalist and the co-founding editor (with his wife) of the Daily Yonder, a website that focuses specifically on the needs of rural communities. As such, it also seeks to overcome stereotypes and help people see the diversity of rural America.

The Daily Yonder is published by the Center for Rural Strategies, a non-profit based in Whitesburg, Kentucky, and Knoxville, Tennessee. The Center had about $832K in revenue in 2014, much of it from well-established foundations like the W.K. Kellogg Foundation (yes, named for the guy who founded the cereal company) and the Nathan Cummings Foundation. Although there’s a big fundraising button on every page, individual or small organization contributions average to only about $20K a year.

Its reach can only be described as tiny at this point: The publication has about 3,500 followers on Twitter and another 3,500 on Facebook (the Facebook page is more regularly updated); its traffic rank is similarly underwhelming. There are some self-inflicted reasons for this: once you get past the frontpage, it’s easy to get lost in the laundry list of topics and inscrutable headlines without any kind of content preview. If clickbait is one extreme of how to present news and analysis, the Yonder is close to the other end.

This also shows a fundamental challenge covering “rural America” as a whole: it’s big, and it’s hard to make local stories exciting for people who aren’t from that specific part of the country. Right now, the frontpage tells me in large letters: “DYNAMIC DELTA LEADERS: EDUCATION IS THE KEY”. Is that a story I want to read? Who knows!

But if you dig, there is lots of good content here. The Viewfinder series, for example, showcases rural photography. The In the Black series is a column that relates the experiences of an underground coal miner. Beyond Coal examines the transition from fossil fuel to renewable energy. The “Speak your piece” columns reflect on many aspects of rural life while staying clear of the vitriol that has become a mainstay of US politics.

Bill Bishop himself followed up on his “The Big Sort” analysis with an insightful article that examines the rapidly increasing percentage of voters who live in “landslide counties” where one of the two parties is likely to win a presidential election with large margins.

Each story has a small Disqus-enabled section for comments, though few stories attract significant discussion. The content is under conventional copyright, and some is syndicated from other sources.

The Verdict

The Daily Yonder deserves to exist, because it provides a much-needed journalistic perspective on rural America. But to truly reach people (rural or not), it will need to strive to become a more engaging source that can successfully perform the difficult task of translating local experiences into public interest journalism with broad appeal to readers in different parts of the country. Because it falls short of that potential, I give it 3 out of 5 stars. If you are interested in authentic perspectives on rural America, I do nevertheless recommend liking their Facebook page or subscribing to their RSS feeds as a way to keep up with their important work.