Reviews by Eloquence

In 1971, Daniel Ellsberg leaked the Pentagon Papers to 19 newspapers. Comprising 7,000 pages, they are an internal history of the Vietnam War compiled by the US government. By doing so, Ellsberg made himself a target of the Nixon administration. The first operation of Nixon’s infamous “White House Plumbers” was the burglary of the offices of Ellsberg’s psychiatrist in order to find materials that could be used to discredit him. Later, members of the group would break into the Watergate hotel, bringing down Nixon’s presidency.

Secrets, first published in 2002, is Ellsberg’s memoir. It focuses on his work for the RAND Corporation and the Pentagon, including the time Ellsberg spent in South Vietnam, and the influences on his thinking that ultimately moved him to become a whistleblower.

A Harvard-educated intellectual, Ellsberg was quickly drawn into the upper echelon of US policymaking. In the early part of his memoir, he describes how, at the Pentagon, secrecy was used not just to conceal information from the public, but also to wage turf wars between departments, with new classifications being invented just to prevent rivals from seeing a certain memo or document.

He is not shy to admit the seductive and addictive nature of access to secrets, and how it breeds contempt from political insiders for the outside world. The public, after all, never knows the true reasons why a political decision was made, so how could the judgment of any member of the public be trusted? Lying to the public in official statements is so common that when lies are used to justify war — as was the case after the Gulf of Tonkin incident — it hardly seems notable to those on the inside.

From skeptic to cynic, from cynic to activist

Yet, Ellsberg was not a critic of this system at the time; he was a willing participant. When he was offered his role at the Pentagon with a specific focus on Vietnam policy, he was at first reluctant not because he questioned US motives in the war — as a Cold Warrior, he shared a desire to limit the spread of communist influence — but because he was skeptical that the war was winnable.

During his two years in South Vietnam, Ellsberg’s skepticism turned into cynicism, as he observed how, with all the unspeakable brutality of the war, there was no strategy or tactic that promised real gains against North Vietnam, short of the total destruction of the country. Moreover, forces on the ground even fabricated entire operations to pretend that “pacification” was around the corner at any moment.

Upon his return to the US, Ellsberg struggled to understand how successive presidencies could push forward a war that was going nowhere and costing hundreds of thousands of lives. Had these presidents simply been victims of their own propaganda? To find out, he participated in the creation of the report known as the Pentagon Papers. And it was his inside knowledge of the report, combined with his exposure to the peace movement, that ultimately caused him to become a whistleblower.

The Pentagon Papers showed that, far from cluelessly bumbling into war, the United States had recklessly escalated a war of aggression against a country that, to begin with, had sought independence from a colonial power, much as America had once done. But here, America had chosen the side of the colonizers.

Presidents Eisenhower, Kennedy and Johnson had willingly signed off on escalation after escalation, even as advisers were telling them that far greater efforts were needed to “win” the war. And it was the Nixon administration that would take the war to levels that can only be described as state terrorism, as Nixon himself promised privately: “We are not going to let this country be defeated by this little shit-ass country.” And he made it clear to Henry Kissinger: “You’re so goddamned concerned about the civilians—and I don’t give a damn. I don’t care.”

While Ellsberg would only learn about these statements when the Nixon White House tapes became public, he did know from insiders that Nixon was lying about pursuing peace in Vietnam, and that he was instead prepared to again escalate the war’s brutality in hopes of forcing North Vietnam to “negotiate” with the United States.

This threat of escalation motivated Ellsberg to try various venues to get the Pentagon Papers out, ultimately releasing them to many newspapers as a dramatic man-hunt against him got underway. The Pentagon Papers didn’t cover the Nixon period, and they mostly reflected poorly on previous Democratic administrations. Nevertheless, Ellsberg felt that making visible how administration after administration had made the same mistakes in Vietnam — and lied about it to the public — would at least help hold Nixon to account.

Nixon, for his part, privately welcomed the leak. It was only when he feared that Ellsberg had more material pertinent to his administration that he fully escalated an effort to silence Ellsberg. Aside from the break-in at his psychiatrist’s office, the Plumbers planned a physical attack against Ellsberg at a rally. In his own autobiography, Gordon Liddy confessed that the Plumbers even considered lacing Ellsberg’s soup with LSD before a public speech, to make him appear like a nutjob.

This criminal campaign failed, and as it was exposed, so did the indictment against Daniel Ellsberg. To this day, Ellsberg remains an outspoken activist against war and secrecy, and in defense of whistleblowers like himself.

The verdict

Secrets is an essential account of how secrecy can turn a republic into an empire, at least where foreign policy and “national security” are concerned. As a book about the Vietnam War, it cannot begin to scratch the surface of the horrors inflicted upon the Vietnamese. But to understand how we can prevent history from repeating itself — how we can undermine the secrecy machine by supporting whistleblowers, and how we must demand transparency whenever our government kills on our behalf — Secrets is as timely and necessary as ever.

Disclosure: I work for Freedom of the Press Foundation, where Ellsberg is a Board member.

As of this writing, James C. Scott is 81 years old. Best known for Seeing Like a State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed (reviews), he is an accomplished scholar of non-state societies. Near the end of his career, Scott is not pulling any punches. Against the Grain seeks to dismantle the standard civilizational narrative — that early state-based agricultural societies were part of a linear progression towards civilization as we understand it today.

Scott demonstrates that the hunter-gatherer lifestyle that preceded sedentary agriculture was egalitarian, relatively peaceful, and allowed for significant leisure time, and that early human cultures combined a variety of approaches to survive. Beyond hunting and gathering, these included shifting agriculture, pastoralism (raising livestock and moving the herd in search of new pastures), and even sedentary agriculture, well before the emergence of states.

Our ancestors were opportunistic and looked for the quickest way to make a living. Agriculture wasn’t necessarily a response to population pressure — depending on the environment, it just offered a more reliable return than hunting and gathering.

In Scott’s narrative, the creation of what he calls “late-Neolithic multi-species resettlement camps” — settlements where humans, livestock, other domesticated animals like dogs, and domesticated plants lived together for extended periods of time — caused never before seen levels of drudgery and misery. The high population concentration led to disease and crop failures, and agricultural cultivation created tedium and reduced cultural complexity.

But it also created opportunities for those who accumulated power to attempt to preserve it. The settlements could be strengthened by abducting and enslaving nomads or members of other communities. By standardizing on cereal grains — “visible, divisible, assessable, storable, transportable, and ‘rationable’” — early states were able to sustain their bureaucracies (and increase elite wealth) through taxation.

A polemic against civilization

War and slavery were not inventions of the state, Scott acknowledges, but it is only through the concentrated power of early states that they could they be brought to a previously unseen scale. When state societies collapsed, many of the enslaved or coerced members (if they survived—a big “if” Scott glosses over a bit too readily) were better off. And state collapse occurred frequently, due to disease, war, starvation, rebellion, and other causes.

Meanwhile, the “barbarians” who did not join state-based societies (and who could not easily be captured because of where they lived) became more sophisticated, extracting tribute from the state — but also selling each other out to serve as mercenaries for hire.

Where Scott’s writing turns into polemic is when he dismisses the idea of “dark ages” (such as the Greek Dark Age or, though he barely writes about it, the period following the collapse of the Roman Empire). The fact that we don’t find monumental buildings, wall paintings, or a strong written tradition, he reminds us, doesn’t mean nothing of interest happened — after all (a point Scott repeats), Homer’s great epic was composed during a “dark age” and transmitted orally.

Scott persuasively marshals the evidence that concentration caused many new hardships, and led to societies which were frequently (if not always) deeply unjust. But he does not attempt to examine the arguments against dispersal, or for large numbers of humans living with each other in close proximity, sharing ideas and beliefs at a pace previously unimagined.

He dismisses “elite displays” such as monuments and temples, but does not write about roads, aqueducts, libraries, poverty relief such as the Cura Annonae, or any legitimate effort to better the life of a community’s members, if such life was organized partially through a state.

Indeed, the word “science” does not appear in the book’s index. Human progression that is the result of better understanding our world and applying that knowledge is too readily dismissed in an effort to keep the book true to its title.

Here, Scott’s book — so critical of ideological views of “civilization” — is itself ideologically committed to rejecting an evidence-based view. “But what of the slaves?” one can imagine Scott saying. “But what of the elites, enriching themselves?” Yes, but what of Euclid, Democritus, Ovid? What of the Library of Alexandria, or the Antikythera mechanism, or the art of Pompeii? What of the religious extremism that followed Rome’s collapse, and probably followed earlier collapses as well?

The verdict

Scott uses language not to obfuscate, but occasionally in ways I would describe as performative. Against the Grain makes frequent use of technical terms from agriculture and anthropology; the writing is dry (though suffused with a dark academic humor) and sometimes repetitive. What keeps the book interesting is its challenge to orthodoxies and its willingness to put things plainly when required, e.g., when writing about slavery.

Against the Grain does re-cast our understanding of history. Scott is correct to critique those who want to see linear progression in human history; a rise from savagery. Deep history that looks at the distant past of our species is crucial to get a clear picture of how we became who we are. Our hunter-gatherer ancestors were far from stupid, and their minds were far from simplistic compared to our own, nor were their lives especially brutal or difficult.

History cannot be understood without examining the accumulation of power and resources, all too often including slaves and other coerced labor. If we want to build morally just societies, we must understand how this accumulation of power is at odds with moral progress, even as it has often enabled scientific or technological progress.

But here ends the usefulness of Scott’s book. The fact that his work celebrates the dispersed life beyond the reach of the state is perhaps precisely why his colleagues can celebrate him as an anarchist academic. His writing poses no threat to real systems of power, because it offers no alternative. It is an important read, but only as a starting point for developing a more nuanced understanding of the human story, correcting misconceptions in the common narrative still taught in schools. In the final analysis, Scott is a rebel without a cause.

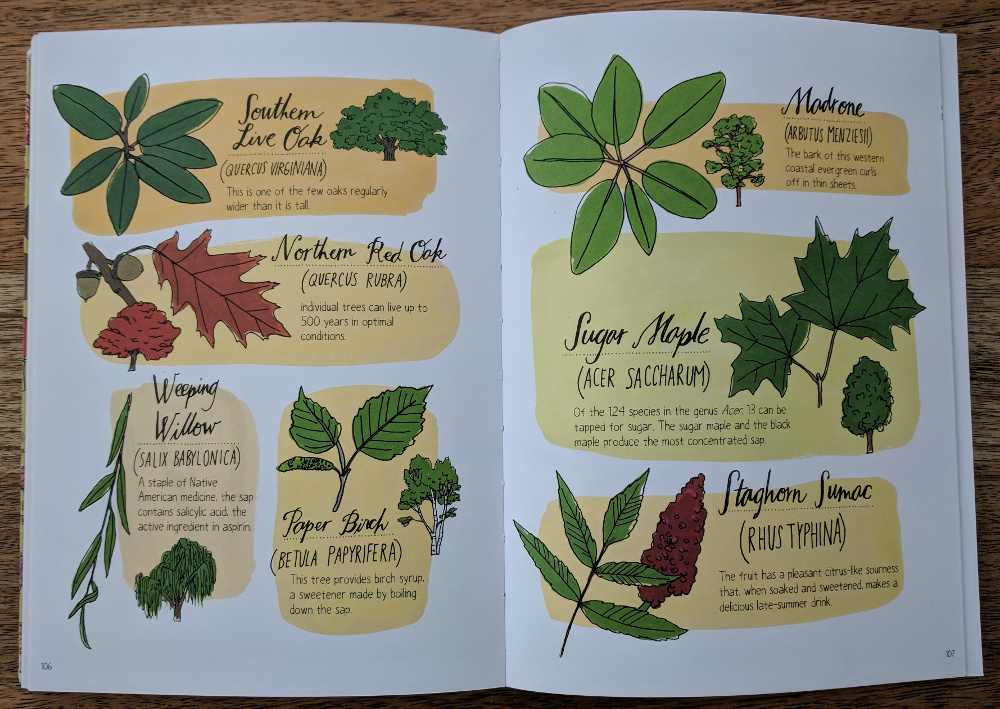

Julia Rothman is an illustrator from New York; in Nature Anatomy: The Curious Parts & Pieces of the Natural World she expresses her love of nature through 223 pages filled with colorful sketches, brief explanations and descriptions.

The art is simple but elegant, conveying the most recognizable characteristics of a leaf, a mushroom or a butterfly in just a few strokes. The organization varies from page to page:

-

annotated illustrations (“anatomy of a flower”) with brief explanations;

-

illustrations without any text or explanation other than a species name;

-

illustrations with brief facts about a species (“Woodchuck: Woodchucks can climb trees if they need to escape”)

-

recipes and other offbeat material, e.g., instructions for printing plant patterns.

This kind of presentation is fairly typical for the book: elegant illustrations accompanied by one or two facts. (Credit: Julia Rothman. Fair use.)

Of course, the book can only sample the natural world (and it does so with a North American bias), but it does attempt to provide some broader explanations as well, e.g., about moon phases or the layers of Earth’s atmosphere.

Some of the text is in cursive, giving the book the feel of an intimate journal. That’s clearly the idea: making the complexity of nature less intimidating by focusing on its beauty and by conveying descriptions and explanations in a casual manner.

At the same time, this approach can no more than whet the appetite for more detailed explanations why nature is the way it is (for which speaking about evolution, which this book hardly does, is essential).

Is this approach suitable for getting young people excited about the natural world? I’m no longer a young reader, but if I was, I bet I would have been in equal parts frustrated and pulled in by this book; pulled in by its art, and frustrated by its failure to go beyond enumerating names and facts. I would give the book 5 stars for art and 3 stars for the text—a good purchase for extending one’s appreciation of the patterns of nature, if not necessarily for understanding them.

The Lion’s Song is an episodic cross-platform video game set in and near Vienna shortly before the First World War. The game features pixel art in a six color sepia palette, which gives it a unique look and feel.

While the game mechanics resemble point-and-click adventure games, this is more of an interactive story. There is no inventory; choices and decisions largely take the place of puzzles.

Each of the four episodes only has about 30 minutes of play time, but the game encourages you to revisit past decisions and explore the connections between the lead characters of each episode (all fictional):

-

Wilma Dörfl, a composer of humble origins who is trying to finish a pivotal piece that could make or break her career, while figuring out her relationship with her mentor;

-

Franz Markert, a painter who is making his debut in Gustav Klimt’s art salon, and who can see “layers” in the personalities of the people around him, while being unable to see them in himself;

-

Emma Recniczek, a mathematician who is looking for guidance from Vienna’s “Radius” (a circle of mathematicians who meet regularly in the backroom of a cafe), but who faces rejection because she is a woman;

-

Albert, the son of a baron who wanted to become a journalist, but finds himself forced to start a military career; during a train journey he meets people who are connected to each of the three characters above.

Franz Markert (second from left) in the art salon (Credit: Mipumi Games GmbH. Fair use.)

The second and third episode have the most depth. It’s fun to be Markert and visit Vienna’s street vendors or the art salon, observing little ghost figures (the “layers” he sees in people’s personalities) appear behind other characters as you walk by them. You get to choose which character you want to paint, which contributes a lot to the replay value of this episode.

Playing Emma, you face important choices regarding your identity and how you present yourself to others, as you try to overcome the societal obstacles to your career as a female mathematician developing a new “theory of change”. Along the way, you briefly meet Markert in a cafe, who is always on the lookout for interesting people to paint.

The sounds and music of the game—the storm and rain outside Wilma’s cabin; the sound of horses in the streets of Vienna; the chatter of the salon—give the game an immersive quality that you might not expect from looking at its low-resolution graphics. The composition which gives the game its title—the Lion’s Song which Wilma composes in the first episode—plays a role similar to the Cloud Atlas composition in David Mitchell’s book of the same name, connecting the threads of story through a tapestry of beautiful music.

Some elements of the story are a bit forced (the confrontation between mathematicians in front of a class of unruly students comes to mind), but for the most part, you become invested in the characters and their fates. The decisions you make truly do have ripple effects throughout the episodes, from the exact composition of the music to the paintings that appear on the walls and the epilogue of the game. Even marginal aspects of the game—credits screens, the “connections” section—are lovingly designed interactive rooms.

You’re unlikely to get more than an evening or two of enjoyment out of this brief game, but the gorgeous art and music, the attention to detail, and the fascinating setting and characters make it unlikely that anyone who enjoys interactive stories would regret this purchase (as of this writing, $10 at GOG).

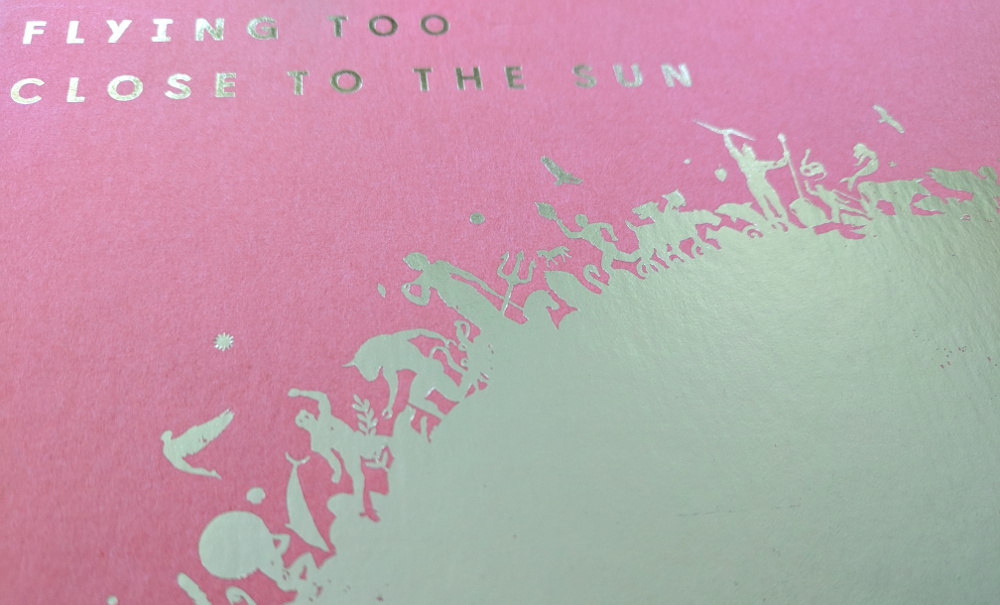

Flying Too Close to the Sun is a large format art-book from Phaidon that examines the influence of classical (Greco-Roman) myths on artistic expression since ancient Greece, for example:

-

the story of Daedalus and Icarus, which inspired the book’s title;

-

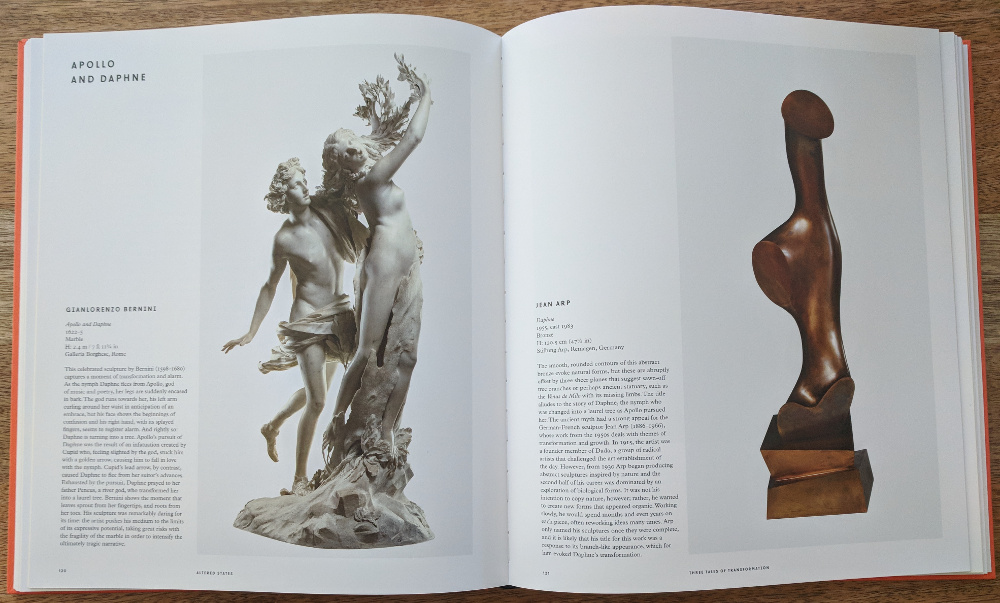

the story of Apollo and Daphne: Daphne escapes the lovestruck Apollo by begging a river god to transform her into a tree;

-

the story of the minotaur and of his slayer, Theseus, the founding hero of Athens.

The book features direct artistic references to these stories, from Greek vases to Renaissance paintings and contemporary sculptures. It also includes some modern art that may or may not intentionally reference classical mythology, but that shows some parallels in theme or expression.

Book cover (partial view). The "flares” of the sun include references to the myths explored in the book. (Credit: Phaidon Press. Fair use.)

At 250 x 290 mm (11 3/8 x 9 7/8 in), the book’s format gives these works of art the space they deserve. The captions are clear and often briefly retell the myth that is being discussed. That makes for some repetition in a single reading, but it also makes it easy to open the book at any page without requiring additional context.

As with any art book like this one, it’s possible to quibble about the works that were chosen or overlooked. For example, it will probably take another generation until editors choose to include art from games like Apotheon, a gorgeous indie platformer that brings the artistic style of ancient Greek pottery to life—to say nothing of the ubiquitous references to mythology in big-budget entertainment like God of War.

Apollo and Daphne (1622-25, Bernini) side-by-side with Jean Arp’s Daphné (1955). (Credit: Phaidon Press. Fair use.)

To me, this speaks to the still austere relationship we have with classical myths. In fact, ancient art was colorful, often lewd, and a form of mass entertainment. It provided common reference points in everyday life, it served propaganda purposes, it blended belief with pure pleasure.

While Flying Too Close to the Sun only hints at this, it is a joy to page through the high quality reproductions and photographs, to explore the content of complex paintings with helpful captions, and to become more familiar with the details of these myths. Recommended.

Before Ed Snowden and Chelsea Manning, there was Daniel Ellsberg, a military analyst who leaked the Pentagon Papers to 19 newspapers in order to inform the American public about the true nature of the Vietnam war. Ellsberg became a committed anti-war activist, but early in his career he was a devoted Cold Warrior. As a strategic analyst for the RAND Corporation, he reviewed and helped shape America’s policy for thermonuclear warfare.

The Doomsday Machine: Confessions of a Nuclear War Planner are Ellsberg’s recollections of this work, combined with a summary of what’s become known about the highly secretive nuclear war plans of the United States and the Soviet Union since then—and how those plans fared in reality during times of crisis. He argues that we have created a Strangelovian doomsday machine which remains on hair-trigger alert, and that the primary goal of nuclear policy at this point should be to dismantle that machine.

Ellsberg documents how close humanity came to self-destruction during the Cold War, and also shows convincingly how the threat of first use remains a key element of US foreign policy, with enemies old and new. This barbaric idea—that it is perfectly reasonable to threaten first use of nuclear warfare as an “option on the table”—must surely die before true progress toward global nuclear disarmament can be made.

How and why did rational people who loved their families and wanted peace for their children participate in planning for global annihilation? Ellsberg provides a brief history lesson on how war planners during World War II embraced with increasing enthusiasm the idea of “strategic bombing”, a euphemism for murdering and maiming large numbers of civilians—men, women and children—in order to “demoralize” an enemy, culminating in the firebombing of Tokyo.

“My Child” by Miyamoto Kenzo, a survivor of the firebombing of Tokyo (Credit: Miyamoto Kenzo. Fair use.)

“It was an ocean of fire. My mother held my hand as we entered the chaotic stream of refugees and headed for the Arakawa embankment. This painting is of something I saw on the way and have never been able to forget. A pregnant woman was standing there like a ghost; at her feet was a child of perhaps three or four years. The child wasn’t moving at all. The way they were lit up by the flames around them—it was a sight I saw at twelve that was so horrifying I’ll never be able to forget it.” — Miyamoto Kenzo, who was 12 at the time of the Tokyo raid. (Source)

This mass murder was rationalized in simple terms: it was said to shorten the war and minimize American casualties. In this context, the idea of using atom bombs was seen as mainly a step up in efficiency, not a fundamental shift in policy. And individuals like Curtis LeMay, who led the firebombing campaign—far from facing charges—would be put in charge of key military and civilian functions as America built up its nuclear arsenal.

The Verdict

Ellsberg’s book is lucid, personal and informative, and his warnings are timely in an America led by a self-described madman who threatens nuclear annihilation of North Korea one day, then brokers theatrical peace talks the next. Some readers will be put off by the heavy use of military acronyms—they’re enumerated in a bare-bones glossary, but often get in the way while reading. There are no photographs, tables or illustrations, but Ellsberg cites his sources extensively, many of which are online.

Countless books have been written about the folly of nuclear weapons, and about the imminent threat to human existence that they continue to pose. Some are more emotionally persuasive than The Doomsday Machine, others provide more complete historical context. Certainly Ellsberg’s level of access during his time as a military analyst gives him an unusual and compelling vantage point. But what this book does exceptionally well is to demonstrate that the dangers of nuclear warfare are not contingent on monstrous individuals being in charge.

Even with better leaders than the ones we have today, these weapons should not exist because they cannot be controlled. With the leaders we have, eliminating them is a moral emergency.

Disclosure: I work for Freedom of the Press Foundation, where Ellsberg is a Board member.

In Humanizing the Economy: Co-operatives in the Age of Capital, John Restakis, a veteran of the Canadian co-op movement, argues for increasing the role of co-operatives and economic democracy, without suggesting that they are a panacea.

Restakis’ argument is firmly grounded in a critique of corporate capitalism; the 2007-2008 financial crisis still loomed very large when the book was published. But Restakis is also highly critical of the disastrous and dehumanizing effects of authoritarian systems with centralized, planned economies.

Instead, much of the book comprises case studies of co-operative economics:

-

the region of Emilia-Romagna in Northeast Italy, where thousands of co-operatives thrive and nearly two out of three citizens are members of co-ops;

-

the fábricas recuperadas (recovered factory) movement in Argentina, a system of co-operative self-management of factories which followed the country’s economic crisis in 2001;

-

the sex worker collectives in India, such as Durbar, a collective of over 65,000 sex workers that combines mutual aid and social services to its members with political advocacy;

-

the Japanese system of consumer co-operatives with more than 28 million members, which provide services such as home delivery, while also incorporating ethical sourcing practices and promoting organic produce;

-

the global movement for fair trade and its sometimes rocky relationship with the co-operative approach.

Unless you’re steeped in the history of co-operatives, it’s quite likely that you’ll find remarkable examples you’ve never heard of. It’s rare for the narrative in conventional Western media to look at examples like these; when there is reporting about economic matters, it’s mostly about whether this or that elected leader will be “business-friendly” and “convince the markets”.

Restakis challenges this thinking about markets as an implacable, amoral force of nature and instead argues that markets are what we make them. An economy that places shared human concerns at its center (and that de-emphasizes the profit motive and the advancement of the individual) is not only possible—it’s one that hundreds of millions of people already participate in.

Members of the Durbar collective of sex workers march against violence and trafficking in Kolkata in 2018. Durbar provides services to sex workers, fights for legalization of sex work, and combats human rights violaitons. (Credit: India Blooms. Fair use.)

Ideas Vs. Ideology

The ideology of corporate capitalism is just that: an ideology that is taught in schools and universities, in media depictions of success and failure, in its self-advertisements. Corporate capitalism also enjoys massive subsidies, including the planet-wide subsidy of tolerating the destruction of the environment instead of taxing it.

Restakis notes that governments have a choice: to continue to underwrite this ideology without question—or to shift resources towards promoting co-operative economics. This kind of support can range from teaching how to run a business co-operatively, to establishing tax incentives, to setting up resource centers (as was done in Emilia Romagna) that provide administrative support to help co-ops succeed.

It’s not as distant a possibility as it may seem. For example, Jeremy Corbyn’s political platform combines nationalization in some areas of the economy with heavy support for the co-op model and workplace democracy in others.

The Verdict

Restakis frontloads his most radical criticisms of corporate capitalism to the early chapters of his book. Humanizing the Economy is a case for incorporating the co-operative model into economic thinking, without offering a blueprint how to do that, or even suggesting that it should be the dominant model of the economy.

For the most part, the author succeeds in making this argument. Given that the book significantly relies on data (numbers of factories recovered in Argentina; numbers of employees in the co-operative sectors of Italy, Spain or Japan; success of credit unions during the financial crisis, etc.), it is disappointing that there is not a single chart or table in the book.

For a book written in 2010, I would also have appreciated more insights into how the Internet enables new forms of cooperation and sharing. Fortunately, other authors have since filled this void, such as Trebor Scholz and Nathan Schneider with “Ours to Hack and to Own: The Rise of Platform Cooperativism”.

As someone still learning about co-operative practices and the solidarity economy, I found John Restakis’ book a useful wayfinder to a lot of examples that I will likely keep coming back to. If you are looking for similar inspiration, I recommend this book.

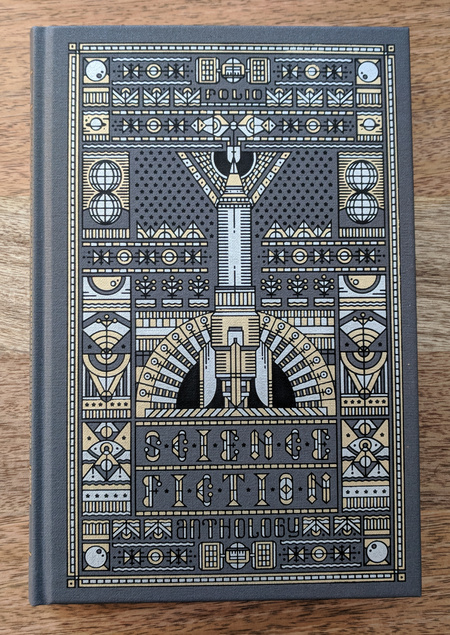

Many sci-fi readers will recognize the name Brian Aldiss (1925–2017), both from his own stories and novels, and from the many anthologies he compiled. The first, for Penguin Science Fiction, was published in 1961. This one is the last, and it is also Aldiss’ final published work. It was published by the Folio Society, which specializes in expensive but beautiful editions of many classic and contemporary works, and which also publishes original anthologies such as this one.

The packaging

You won’t find this book on Amazon, and it is currently advertised at USD 53.95—a hefty price for a single volume. But that’s the Folio way—these are books for bibliophiles, whether that describes yourself or someone you care about. The cover, in this case, is block printed on buckram (cloth) and features a beautiful abstract illustration of a rocketship:

Cover for the Folio Society Science Fiction Anthology (Credit: Folio Society / own photograph. Fair use.)

It’s a pleasure to hold this book and to examine the detail of the print:

Detail of Folio Society Science Fiction Anthology book cover (Credit: Folio Society / own photograph. Fair use.)

The book comes with a slipcase cover, which looks more stylish than a typical dust cover, and doesn’t get in the way while reading. Like many Folio books, the anthology features commissioned illustrations for several of the stories in the anthology:

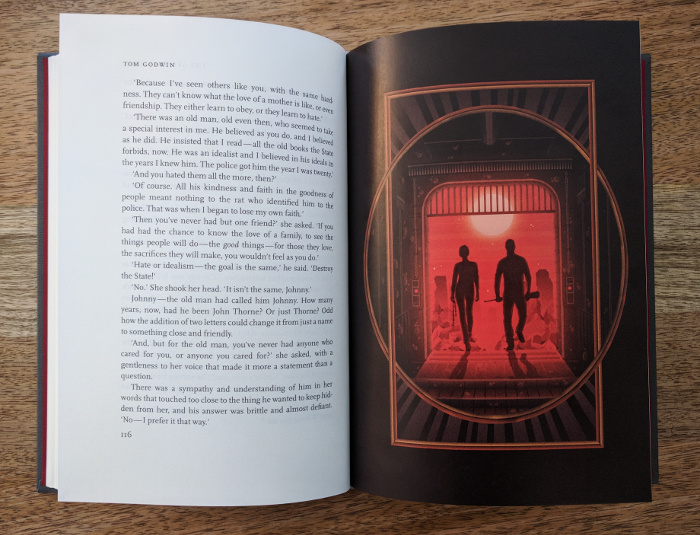

Pages from Folio Society Science Fiction Anthology. (Credit: Folio Society. Fair use.)

The stories

The stories are arranged in chronological order. They are:

-

Micromégas by Voltaire (1752)

-

The Star by H.G. Wells (1897)

-

Bridle and Saddle by Isaac Asimov (1942)

-

The Greater Thing by Tom Godwin (1954)

-

Grandpa by James H. Schmitz (1955)

-

Poor Little Warrior! by Brian Aldiss (1959)

-

Recall Mechanism by Philip K. Dick (1959)

-

An Alien Agony by Harry Harrison (1962)

-

Searchlight by Robert Heinlein (1962)

-

Clarita by Anna Kavan (1970)

-

And I Awoke and Found Me Here on the Cold Hill’s Side by James Tiptree Jr., pen name of Alice Sheldon (1972)

-

The Day They Raised the Titanic by Alice Wilson (2015)

As is evident from this list, there is only one recent story, and many are from around the Golden Age of sci-fi—don’t expect to find tales of posthuman existence or hard sci-fi grounded in our current knowledge of space travel and planetary exploration. That said, I found several of the stories quite stimulating:

-

Bridle and Saddle—this story is part of Asimov’s Foundation saga, but requires no familiarity with it. The administrator of a lightly populated planet that exercises centralized control over all knowledge on behalf of a multi-planetary society is faced with threats from the planet’s powerful neighbors, and from discontents at home. Will he be able to hold onto power without violence, which he calls “the last refuge of the incompetent”?

-

Grandpa—a kid who is part of a colonization team stewards a small expedition on a large lily-pad-shaped hybrid plant/animal called “Grandpa”. Grandpa, it turns out, is not quite as simplistic a creature as everyone thought, and our protagonist has to find a way out of an increasingly desperate situation. Although more than 60 years old, there’s nothing in this story that dates it to its era.

-

An Alien Agony—science and religion clash on a planet that has very little experience with either. A beautiful little “loss of innocence” story.

-

And I Awoke and Found Me Here on the Cold Hill’s Side—this story caught me by surprise in that I’ve never encountered its premise before: that humans are uniquely attracted to aliens (both sexually and in terms of pure curiosity), while other species find this behavior very amusing. A story that explores xenophobia and xenophilia, and makes you think about what alien encounters would actually be like.

The illustrations by Florian Schommer stylistically follow the books’s chronology (“as the stories move towards the modern age a palette of deep oranges and reds is gradually introduced”, to quote Folio’s description), and the polygons and circles that frame each picture make them look like windows into different worlds.

The Verdict

I quite enjoyed about half the stories in the volume, and some of them (like Grandpa) are true gems of the genre. As with every Folio Society book I have the pleasure to own, this is a beautifully made physical object. It is also a lovely gift for any sci-fi lover. 3.5 stars, rounded up because of the appreciation of the book as an object that endures in Folio’s publications.

Triumph of Christianity over Paganism. 16th century fresco by Tommaso Laureti decorating the ceiling of the Constantine Hall in the Vatican Palace. (Credit: Jean-Pol GRANDMONT. License: CC-BY-SA.)

From the comfortable distance of a privileged life in the 21st century, it is perhaps easy to see that the Roman Empire was doomed. Having replaced oligarchy with permanent dictatorship, the empire sustained its ambitious civilization-building effort through slave labor and the spoils of expansionist wars. Internal unrest and foreign invasions were sure to follow. What role did religion play in this collapse?

Catherine Nixey’s book, The Darkening Age, makes the case that Christianity added fuel to the fire: quite literally in the form of book burnings or the melting down of statues, and figuratively through its embrace of a fanatical, exclusionary belief system that made it impossible to re-build or preserve a crumbling society.

Nixey knows her stuff; she studied Classics at Cambridge and subsequently worked as a Classics teacher for several years, but she is first and foremost a journalist, and her book tells history much in the way a writer like Erik Larson does: as a story with characters, sometimes picking the source that best fits the narrative, rather than attempting a neutral presentation of all possibilities of what happened.

In evidence of her thesis, Nixey marshals both “pagan” and Christian primary sources and cites recent modern research, such as Eberhard Sauer’s The Archaeology of Religious Hatred (Tempus, 2003) and Dirk Rohmann’s Christianity, Book-Burning and Censorship in Late Antiquity: Studies in Text Transmission (De Gruyter, 2016). The key themes of her book can be summarized as follows:

-

Early Christianity was a fanatical religion focused on martyrdom, suffering, and death.

-

While Christians were certainly persecuted at various times, the extent of that persecution was dramatically exaggerated.

-

As Christians gained power, they turned the tables and engaged in systematic destructions of temples, statues, and books, and forced conversion through acts of terror and murder.

-

The church did play an important role preserving what little ancient knowledge was preserved — but it did so extremely selectively (omitting materials considered too salacious, or those seen to contradict Christian doctrine). Effectively, much of the earlier culture was annihilated, including irreplaceable philosophical and scientific texts.

-

Rome’s polytheistic culture was sexually permissive and tolerant of argument and debate. Christian writers, in contrast, replaced debate with dogma. They railed against the “tyranny of joy” and laid the foundation for centuries of Christian sexual repression, associating pleasure with shame in ways that reverberate to this day.

You may think there is a consensus among modern historians about these claims, but there is not (this is, after all, a society still rooted in the very origins that are at issue). As Nixey acknowledges, many historians have painted a very different picture. Today you’re just as likely to read that polytheism simply grew out of fashion, or that the Dark Ages “weren’t really dark”, or that Christianity was a benign and civilizing influence during a chaotic time. Don’t even think to draw modern parallels!

Yet, as Nixey demonstrates, those parallels are all too obvious, and they are instructive, which is indeed why apologists prefer to ignore them. Nixey points out that Christian statue-smashers defaced the same beautiful statue of Athena at Palmyra that ISIS would completely obliterate more than a millennium and a half later, with similar “reasoning” (“The Prophet Muhammad commanded us to shatter and destroy statues.”).

Apologists claim that when early Christians burned books about “sorcery”, surely they contained just that—not science or philosophy! But we find no such nuance when we look to modern claims of “sorcery” by religious fanatics, such as when the Taliban sacked Afghanistan’s Meteorological Authority in 1996 because weather forecasting is, of course, sorcery. Christian fanatics who call Harry Potter “Witchcraft Repackaged” don’t draw the distinction between literature and religion.

Just as it did not in ancient Rome, tolerance rarely lasts long after religions gain political power. In the United States, where evangelical Christianity still has somewhat of an underdog status, religious extremists who oppose evolutionary theory merely ask that schools and universities “teach the controversy” (while funneling taxpayer funds to schools that teach only creationism). In Turkey, where Islamists have substantial political power, evolutionary theory was recently banned from textbooks.

In short, the counterarguments to Nixey’s thesis fall apart precisely when one observes and compares religious fanaticism in any of its modern manifestations that are more easily studied than texts from the 4th or 5th century (and less subject to manipulation, omission, and re-interpretation over the centuries). The fanaticism Nixey describes is, sadly, far from unique or remarkable, and its intellectual legacy is still with us today.

Learning from collapse

In The Queen of Spades, a short story with supernatural overtones, Alexander Pushkin wrote: “Two fixed ideas can no more exist together in the moral world than two bodies can occupy one and the same place in the physical world.“ By that standard, two ideas could not be more fixed than those of polytheism and monotheism. How does one tolerate the intolerant?

Christianity was not the only cult of its time that made singular claims to the truth; it was merely the one that ultimately prevailed. But far from being a force for peace or preservation, it added fuel to the fire of Rome’s—probably inevitable—collapse.

A fierce, hateful religion (and that is what this iteration of Christianity was) could never have gained such momentum in a healthy, stable society. But under conditions of instability and inequality, it accelerated and ultimately cemented the loss of a civilization. That is the key lesson to carry into the 21st century, and Nixey deserves much credit for writing an accessible book to do so.

Night in the Woods is an adventure game available for virtually all platforms (as of this writing: Windows, macOS, Linux, PS4, Xbox One, Switch). The game mostly takes place from the perspective of college drop-out Mae Borowski, whose return to her hometown of Possum Springs leads to reunions, conflicts, weird dreams, and a gradually unfolding mystery.

The town is inhabited by anthropomorphic animals (and, oddly, by some actual animals); Mae herself is a 20-year-old cat. The player controls Mae in a manner similar to a jump-and-run game, but with the sense of safety of a point-and-click adventure. While there are areas of the game world that can be a bit tricky to reach, there is very little puzzle-solving.

From time to time, a scene turns into a mini-game (playing the bass guitar, stealing an item from a shop, hitting objects with a baseball bat). You often only get one shot at these games, and whether you succeed or fail will reveal small variations in the story.

While the story is more or less on rails, the game’s characters keep you engaged. There’s Mae’s old friend Gregg, a fox whose short attention span doesn’t seem to get in the way of his employment at the “Snack Falcon”. As time goes on, the depth of his love for his boyfriend, a bear named Angus, is revealed, who seems to be Gregg’s best hope of growing up.

From left to right: Germ, Bea, Angus, Mae, and Gregg at band practice. (Credit: Infinite Fall. Fair use.)

There’s Beatrice “Bea” Santello, a goth who seems initially hostile but who opens up after Mae spends more time with her. And of course there are Mae’s parents, who struggle to get their daughter to tell them what exactly caused her to drop out of college.

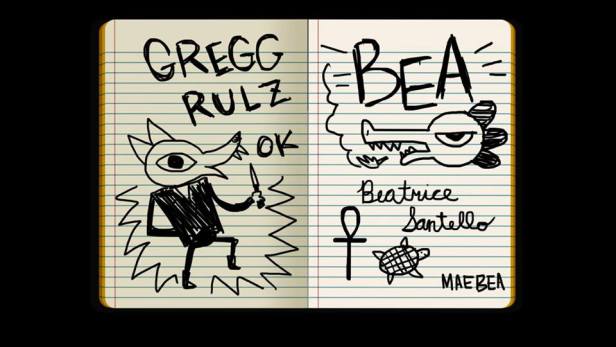

When speaking with other characters, you are often given multiple dialog options, but what you can say is constrained by Mae’s perspective on the world as a 20-year-old with … issues. After many experiences, Mae automatically scribbles notes into her personal journal, which are observations like “GREGG RULZ OK” or “THOUGHT: THIS PLACE IS FALLING APART”, often accompanied by cartoons.

As the game progresses, Mae draws little notes in her journal. (Credit: Infinite Fall. Fair use.)

Over time, the mystery at the heart of the story gradually becomes apparent. Mae experiences weird dreams and a growing sense of anxiety, and she witnesses strange goings-on in Possum Springs. The ultimate “reveal” is less important than Mae’s struggle to come to terms with her own fragility. There are discussions of death and religion, but they are meditative, not proselytizing.

Night in the Woods is a gorgeous game: the characters, landscapes and animations are simple but beautiful, enriched by context-specific background music (listen to the soundtrack). The writing is terrific and the pacing is generally good; the early game can feel a bit drawn out.

The main controls are easy to master, though some of the mini-games can feel a bit unfair the first time around. You’ll probably get at least one replay out of the game, to discover hidden branches of the story you missed the first time around, and to master the various mini-games.

On the Nintendo Switch, which is the version we played, the load times can be a bit frustrating: going from one screen to another can trigger a five second “loading” animation, and it’s in the nature of the game’s controls that you might do so accidentally a few times.

The Verdict

I highly recommend giving this game a chance, unless you’re put off by some of the themes of young adult drama and prefer your games to be more challenging. Currently, the game goes for $20 on Steam, which is a decent price for the amount of content that’s packed in here. While the game is not without its minor frustrations, I would give it 4.5 out of 5 stars, rounded up.