Reviews by Eloquence

Before Ed Snowden and Chelsea Manning, there was Daniel Ellsberg, a military analyst who leaked the Pentagon Papers to 19 newspapers in order to inform the American public about the true nature of the Vietnam war. Ellsberg became a committed anti-war activist, but early in his career he was a devoted Cold Warrior. As a strategic analyst for the RAND Corporation, he reviewed and helped shape America’s policy for thermonuclear warfare.

The Doomsday Machine: Confessions of a Nuclear War Planner are Ellsberg’s recollections of this work, combined with a summary of what’s become known about the highly secretive nuclear war plans of the United States and the Soviet Union since then—and how those plans fared in reality during times of crisis. He argues that we have created a Strangelovian doomsday machine which remains on hair-trigger alert, and that the primary goal of nuclear policy at this point should be to dismantle that machine.

Ellsberg documents how close humanity came to self-destruction during the Cold War, and also shows convincingly how the threat of first use remains a key element of US foreign policy, with enemies old and new. This barbaric idea—that it is perfectly reasonable to threaten first use of nuclear warfare as an “option on the table”—must surely die before true progress toward global nuclear disarmament can be made.

How and why did rational people who loved their families and wanted peace for their children participate in planning for global annihilation? Ellsberg provides a brief history lesson on how war planners during World War II embraced with increasing enthusiasm the idea of “strategic bombing”, a euphemism for murdering and maiming large numbers of civilians—men, women and children—in order to “demoralize” an enemy, culminating in the firebombing of Tokyo.

“My Child” by Miyamoto Kenzo, a survivor of the firebombing of Tokyo (Credit: Miyamoto Kenzo. Fair use.)

“It was an ocean of fire. My mother held my hand as we entered the chaotic stream of refugees and headed for the Arakawa embankment. This painting is of something I saw on the way and have never been able to forget. A pregnant woman was standing there like a ghost; at her feet was a child of perhaps three or four years. The child wasn’t moving at all. The way they were lit up by the flames around them—it was a sight I saw at twelve that was so horrifying I’ll never be able to forget it.” — Miyamoto Kenzo, who was 12 at the time of the Tokyo raid. (Source)

This mass murder was rationalized in simple terms: it was said to shorten the war and minimize American casualties. In this context, the idea of using atom bombs was seen as mainly a step up in efficiency, not a fundamental shift in policy. And individuals like Curtis LeMay, who led the firebombing campaign—far from facing charges—would be put in charge of key military and civilian functions as America built up its nuclear arsenal.

The Verdict

Ellsberg’s book is lucid, personal and informative, and his warnings are timely in an America led by a self-described madman who threatens nuclear annihilation of North Korea one day, then brokers theatrical peace talks the next. Some readers will be put off by the heavy use of military acronyms—they’re enumerated in a bare-bones glossary, but often get in the way while reading. There are no photographs, tables or illustrations, but Ellsberg cites his sources extensively, many of which are online.

Countless books have been written about the folly of nuclear weapons, and about the imminent threat to human existence that they continue to pose. Some are more emotionally persuasive than The Doomsday Machine, others provide more complete historical context. Certainly Ellsberg’s level of access during his time as a military analyst gives him an unusual and compelling vantage point. But what this book does exceptionally well is to demonstrate that the dangers of nuclear warfare are not contingent on monstrous individuals being in charge.

Even with better leaders than the ones we have today, these weapons should not exist because they cannot be controlled. With the leaders we have, eliminating them is a moral emergency.

Disclosure: I work for Freedom of the Press Foundation, where Ellsberg is a Board member.

In Humanizing the Economy: Co-operatives in the Age of Capital, John Restakis, a veteran of the Canadian co-op movement, argues for increasing the role of co-operatives and economic democracy, without suggesting that they are a panacea.

Restakis’ argument is firmly grounded in a critique of corporate capitalism; the 2007-2008 financial crisis still loomed very large when the book was published. But Restakis is also highly critical of the disastrous and dehumanizing effects of authoritarian systems with centralized, planned economies.

Instead, much of the book comprises case studies of co-operative economics:

-

the region of Emilia-Romagna in Northeast Italy, where thousands of co-operatives thrive and nearly two out of three citizens are members of co-ops;

-

the fábricas recuperadas (recovered factory) movement in Argentina, a system of co-operative self-management of factories which followed the country’s economic crisis in 2001;

-

the sex worker collectives in India, such as Durbar, a collective of over 65,000 sex workers that combines mutual aid and social services to its members with political advocacy;

-

the Japanese system of consumer co-operatives with more than 28 million members, which provide services such as home delivery, while also incorporating ethical sourcing practices and promoting organic produce;

-

the global movement for fair trade and its sometimes rocky relationship with the co-operative approach.

Unless you’re steeped in the history of co-operatives, it’s quite likely that you’ll find remarkable examples you’ve never heard of. It’s rare for the narrative in conventional Western media to look at examples like these; when there is reporting about economic matters, it’s mostly about whether this or that elected leader will be “business-friendly” and “convince the markets”.

Restakis challenges this thinking about markets as an implacable, amoral force of nature and instead argues that markets are what we make them. An economy that places shared human concerns at its center (and that de-emphasizes the profit motive and the advancement of the individual) is not only possible—it’s one that hundreds of millions of people already participate in.

Members of the Durbar collective of sex workers march against violence and trafficking in Kolkata in 2018. Durbar provides services to sex workers, fights for legalization of sex work, and combats human rights violaitons. (Credit: India Blooms. Fair use.)

Ideas Vs. Ideology

The ideology of corporate capitalism is just that: an ideology that is taught in schools and universities, in media depictions of success and failure, in its self-advertisements. Corporate capitalism also enjoys massive subsidies, including the planet-wide subsidy of tolerating the destruction of the environment instead of taxing it.

Restakis notes that governments have a choice: to continue to underwrite this ideology without question—or to shift resources towards promoting co-operative economics. This kind of support can range from teaching how to run a business co-operatively, to establishing tax incentives, to setting up resource centers (as was done in Emilia Romagna) that provide administrative support to help co-ops succeed.

It’s not as distant a possibility as it may seem. For example, Jeremy Corbyn’s political platform combines nationalization in some areas of the economy with heavy support for the co-op model and workplace democracy in others.

The Verdict

Restakis frontloads his most radical criticisms of corporate capitalism to the early chapters of his book. Humanizing the Economy is a case for incorporating the co-operative model into economic thinking, without offering a blueprint how to do that, or even suggesting that it should be the dominant model of the economy.

For the most part, the author succeeds in making this argument. Given that the book significantly relies on data (numbers of factories recovered in Argentina; numbers of employees in the co-operative sectors of Italy, Spain or Japan; success of credit unions during the financial crisis, etc.), it is disappointing that there is not a single chart or table in the book.

For a book written in 2010, I would also have appreciated more insights into how the Internet enables new forms of cooperation and sharing. Fortunately, other authors have since filled this void, such as Trebor Scholz and Nathan Schneider with “Ours to Hack and to Own: The Rise of Platform Cooperativism”.

As someone still learning about co-operative practices and the solidarity economy, I found John Restakis’ book a useful wayfinder to a lot of examples that I will likely keep coming back to. If you are looking for similar inspiration, I recommend this book.

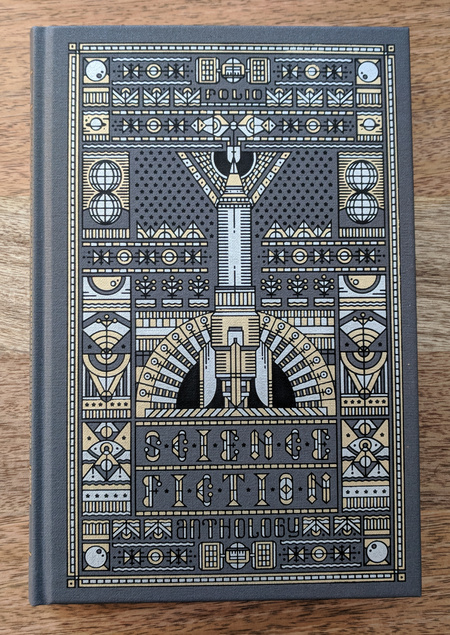

Many sci-fi readers will recognize the name Brian Aldiss (1925–2017), both from his own stories and novels, and from the many anthologies he compiled. The first, for Penguin Science Fiction, was published in 1961. This one is the last, and it is also Aldiss’ final published work. It was published by the Folio Society, which specializes in expensive but beautiful editions of many classic and contemporary works, and which also publishes original anthologies such as this one.

The packaging

You won’t find this book on Amazon, and it is currently advertised at USD 53.95—a hefty price for a single volume. But that’s the Folio way—these are books for bibliophiles, whether that describes yourself or someone you care about. The cover, in this case, is block printed on buckram (cloth) and features a beautiful abstract illustration of a rocketship:

Cover for the Folio Society Science Fiction Anthology (Credit: Folio Society / own photograph. Fair use.)

It’s a pleasure to hold this book and to examine the detail of the print:

Detail of Folio Society Science Fiction Anthology book cover (Credit: Folio Society / own photograph. Fair use.)

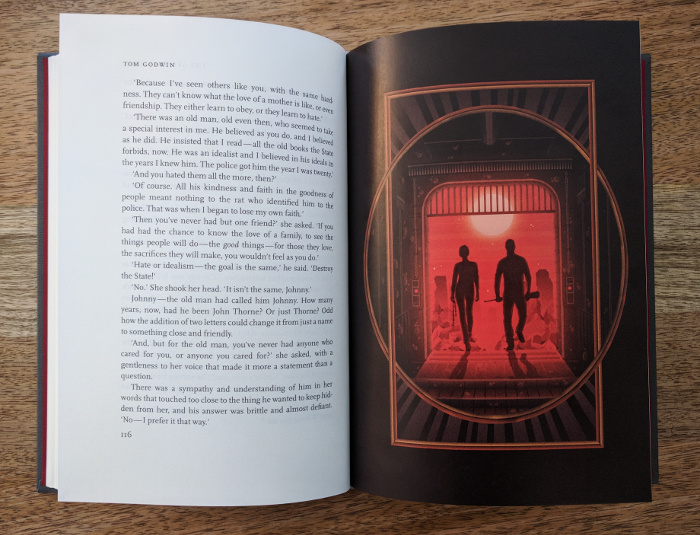

The book comes with a slipcase cover, which looks more stylish than a typical dust cover, and doesn’t get in the way while reading. Like many Folio books, the anthology features commissioned illustrations for several of the stories in the anthology:

Pages from Folio Society Science Fiction Anthology. (Credit: Folio Society. Fair use.)

The stories

The stories are arranged in chronological order. They are:

-

Micromégas by Voltaire (1752)

-

The Star by H.G. Wells (1897)

-

Bridle and Saddle by Isaac Asimov (1942)

-

The Greater Thing by Tom Godwin (1954)

-

Grandpa by James H. Schmitz (1955)

-

Poor Little Warrior! by Brian Aldiss (1959)

-

Recall Mechanism by Philip K. Dick (1959)

-

An Alien Agony by Harry Harrison (1962)

-

Searchlight by Robert Heinlein (1962)

-

Clarita by Anna Kavan (1970)

-

And I Awoke and Found Me Here on the Cold Hill’s Side by James Tiptree Jr., pen name of Alice Sheldon (1972)

-

The Day They Raised the Titanic by Alice Wilson (2015)

As is evident from this list, there is only one recent story, and many are from around the Golden Age of sci-fi—don’t expect to find tales of posthuman existence or hard sci-fi grounded in our current knowledge of space travel and planetary exploration. That said, I found several of the stories quite stimulating:

-

Bridle and Saddle—this story is part of Asimov’s Foundation saga, but requires no familiarity with it. The administrator of a lightly populated planet that exercises centralized control over all knowledge on behalf of a multi-planetary society is faced with threats from the planet’s powerful neighbors, and from discontents at home. Will he be able to hold onto power without violence, which he calls “the last refuge of the incompetent”?

-

Grandpa—a kid who is part of a colonization team stewards a small expedition on a large lily-pad-shaped hybrid plant/animal called “Grandpa”. Grandpa, it turns out, is not quite as simplistic a creature as everyone thought, and our protagonist has to find a way out of an increasingly desperate situation. Although more than 60 years old, there’s nothing in this story that dates it to its era.

-

An Alien Agony—science and religion clash on a planet that has very little experience with either. A beautiful little “loss of innocence” story.

-

And I Awoke and Found Me Here on the Cold Hill’s Side—this story caught me by surprise in that I’ve never encountered its premise before: that humans are uniquely attracted to aliens (both sexually and in terms of pure curiosity), while other species find this behavior very amusing. A story that explores xenophobia and xenophilia, and makes you think about what alien encounters would actually be like.

The illustrations by Florian Schommer stylistically follow the books’s chronology (“as the stories move towards the modern age a palette of deep oranges and reds is gradually introduced”, to quote Folio’s description), and the polygons and circles that frame each picture make them look like windows into different worlds.

The Verdict

I quite enjoyed about half the stories in the volume, and some of them (like Grandpa) are true gems of the genre. As with every Folio Society book I have the pleasure to own, this is a beautifully made physical object. It is also a lovely gift for any sci-fi lover. 3.5 stars, rounded up because of the appreciation of the book as an object that endures in Folio’s publications.

Triumph of Christianity over Paganism. 16th century fresco by Tommaso Laureti decorating the ceiling of the Constantine Hall in the Vatican Palace. (Credit: Jean-Pol GRANDMONT. License: CC-BY-SA.)

From the comfortable distance of a privileged life in the 21st century, it is perhaps easy to see that the Roman Empire was doomed. Having replaced oligarchy with permanent dictatorship, the empire sustained its ambitious civilization-building effort through slave labor and the spoils of expansionist wars. Internal unrest and foreign invasions were sure to follow. What role did religion play in this collapse?

Catherine Nixey’s book, The Darkening Age, makes the case that Christianity added fuel to the fire: quite literally in the form of book burnings or the melting down of statues, and figuratively through its embrace of a fanatical, exclusionary belief system that made it impossible to re-build or preserve a crumbling society.

Nixey knows her stuff; she studied Classics at Cambridge and subsequently worked as a Classics teacher for several years, but she is first and foremost a journalist, and her book tells history much in the way a writer like Erik Larson does: as a story with characters, sometimes picking the source that best fits the narrative, rather than attempting a neutral presentation of all possibilities of what happened.

In evidence of her thesis, Nixey marshals both “pagan” and Christian primary sources and cites recent modern research, such as Eberhard Sauer’s The Archaeology of Religious Hatred (Tempus, 2003) and Dirk Rohmann’s Christianity, Book-Burning and Censorship in Late Antiquity: Studies in Text Transmission (De Gruyter, 2016). The key themes of her book can be summarized as follows:

-

Early Christianity was a fanatical religion focused on martyrdom, suffering, and death.

-

While Christians were certainly persecuted at various times, the extent of that persecution was dramatically exaggerated.

-

As Christians gained power, they turned the tables and engaged in systematic destructions of temples, statues, and books, and forced conversion through acts of terror and murder.

-

The church did play an important role preserving what little ancient knowledge was preserved — but it did so extremely selectively (omitting materials considered too salacious, or those seen to contradict Christian doctrine). Effectively, much of the earlier culture was annihilated, including irreplaceable philosophical and scientific texts.

-

Rome’s polytheistic culture was sexually permissive and tolerant of argument and debate. Christian writers, in contrast, replaced debate with dogma. They railed against the “tyranny of joy” and laid the foundation for centuries of Christian sexual repression, associating pleasure with shame in ways that reverberate to this day.

You may think there is a consensus among modern historians about these claims, but there is not (this is, after all, a society still rooted in the very origins that are at issue). As Nixey acknowledges, many historians have painted a very different picture. Today you’re just as likely to read that polytheism simply grew out of fashion, or that the Dark Ages “weren’t really dark”, or that Christianity was a benign and civilizing influence during a chaotic time. Don’t even think to draw modern parallels!

Yet, as Nixey demonstrates, those parallels are all too obvious, and they are instructive, which is indeed why apologists prefer to ignore them. Nixey points out that Christian statue-smashers defaced the same beautiful statue of Athena at Palmyra that ISIS would completely obliterate more than a millennium and a half later, with similar “reasoning” (“The Prophet Muhammad commanded us to shatter and destroy statues.”).

Apologists claim that when early Christians burned books about “sorcery”, surely they contained just that—not science or philosophy! But we find no such nuance when we look to modern claims of “sorcery” by religious fanatics, such as when the Taliban sacked Afghanistan’s Meteorological Authority in 1996 because weather forecasting is, of course, sorcery. Christian fanatics who call Harry Potter “Witchcraft Repackaged” don’t draw the distinction between literature and religion.

Just as it did not in ancient Rome, tolerance rarely lasts long after religions gain political power. In the United States, where evangelical Christianity still has somewhat of an underdog status, religious extremists who oppose evolutionary theory merely ask that schools and universities “teach the controversy” (while funneling taxpayer funds to schools that teach only creationism). In Turkey, where Islamists have substantial political power, evolutionary theory was recently banned from textbooks.

In short, the counterarguments to Nixey’s thesis fall apart precisely when one observes and compares religious fanaticism in any of its modern manifestations that are more easily studied than texts from the 4th or 5th century (and less subject to manipulation, omission, and re-interpretation over the centuries). The fanaticism Nixey describes is, sadly, far from unique or remarkable, and its intellectual legacy is still with us today.

Learning from collapse

In The Queen of Spades, a short story with supernatural overtones, Alexander Pushkin wrote: “Two fixed ideas can no more exist together in the moral world than two bodies can occupy one and the same place in the physical world.“ By that standard, two ideas could not be more fixed than those of polytheism and monotheism. How does one tolerate the intolerant?

Christianity was not the only cult of its time that made singular claims to the truth; it was merely the one that ultimately prevailed. But far from being a force for peace or preservation, it added fuel to the fire of Rome’s—probably inevitable—collapse.

A fierce, hateful religion (and that is what this iteration of Christianity was) could never have gained such momentum in a healthy, stable society. But under conditions of instability and inequality, it accelerated and ultimately cemented the loss of a civilization. That is the key lesson to carry into the 21st century, and Nixey deserves much credit for writing an accessible book to do so.

Night in the Woods is an adventure game available for virtually all platforms (as of this writing: Windows, macOS, Linux, PS4, Xbox One, Switch). The game mostly takes place from the perspective of college drop-out Mae Borowski, whose return to her hometown of Possum Springs leads to reunions, conflicts, weird dreams, and a gradually unfolding mystery.

The town is inhabited by anthropomorphic animals (and, oddly, by some actual animals); Mae herself is a 20-year-old cat. The player controls Mae in a manner similar to a jump-and-run game, but with the sense of safety of a point-and-click adventure. While there are areas of the game world that can be a bit tricky to reach, there is very little puzzle-solving.

From time to time, a scene turns into a mini-game (playing the bass guitar, stealing an item from a shop, hitting objects with a baseball bat). You often only get one shot at these games, and whether you succeed or fail will reveal small variations in the story.

While the story is more or less on rails, the game’s characters keep you engaged. There’s Mae’s old friend Gregg, a fox whose short attention span doesn’t seem to get in the way of his employment at the “Snack Falcon”. As time goes on, the depth of his love for his boyfriend, a bear named Angus, is revealed, who seems to be Gregg’s best hope of growing up.

From left to right: Germ, Bea, Angus, Mae, and Gregg at band practice. (Credit: Infinite Fall. Fair use.)

There’s Beatrice “Bea” Santello, a goth who seems initially hostile but who opens up after Mae spends more time with her. And of course there are Mae’s parents, who struggle to get their daughter to tell them what exactly caused her to drop out of college.

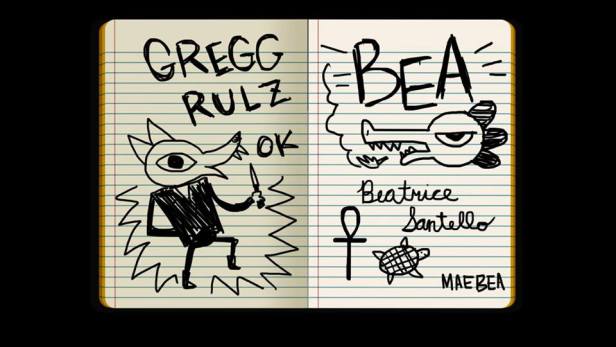

When speaking with other characters, you are often given multiple dialog options, but what you can say is constrained by Mae’s perspective on the world as a 20-year-old with … issues. After many experiences, Mae automatically scribbles notes into her personal journal, which are observations like “GREGG RULZ OK” or “THOUGHT: THIS PLACE IS FALLING APART”, often accompanied by cartoons.

As the game progresses, Mae draws little notes in her journal. (Credit: Infinite Fall. Fair use.)

Over time, the mystery at the heart of the story gradually becomes apparent. Mae experiences weird dreams and a growing sense of anxiety, and she witnesses strange goings-on in Possum Springs. The ultimate “reveal” is less important than Mae’s struggle to come to terms with her own fragility. There are discussions of death and religion, but they are meditative, not proselytizing.

Night in the Woods is a gorgeous game: the characters, landscapes and animations are simple but beautiful, enriched by context-specific background music (listen to the soundtrack). The writing is terrific and the pacing is generally good; the early game can feel a bit drawn out.

The main controls are easy to master, though some of the mini-games can feel a bit unfair the first time around. You’ll probably get at least one replay out of the game, to discover hidden branches of the story you missed the first time around, and to master the various mini-games.

On the Nintendo Switch, which is the version we played, the load times can be a bit frustrating: going from one screen to another can trigger a five second “loading” animation, and it’s in the nature of the game’s controls that you might do so accidentally a few times.

The Verdict

I highly recommend giving this game a chance, unless you’re put off by some of the themes of young adult drama and prefer your games to be more challenging. Currently, the game goes for $20 on Steam, which is a decent price for the amount of content that’s packed in here. While the game is not without its minor frustrations, I would give it 4.5 out of 5 stars, rounded up.

The crime at the center of Stephen King’s, The Outsider is gruesome even by the horror writer’s standards: the sadistic murder of a child. The suspect is Terry Maitland, a baseball coach in the fictional town of Flint City. Early on, it looks like the cops have this one in the bag: multiple witnesses and DNA evidence appear to tie Maitland to the crime. But then a single question threatens detective Ralph Anderson’s grip on reality: can a murderer be in two places at the same time?

The hardcover edition of The Outsider has 576 pages, but I found myself breezing through the book in a single weekend, thanks to King’s masterful pacing of the story. While the book ultimately follows a fairly genre-typical path, the entry of a beloved character from King’s recent Bill Hodges trilogy (Mr. Mercedes, Finders Keepers, End of Watch) keeps things interesting until the end. 4 out of 5 stars.

If you’ve been wondering whether you should make a Mastodon account, the answer is, yes, you should. (If you haven’t been wondering, you might want to start here to read more about the project.) While Mastodon has more in common with Twitter than with Facebook, it is also entirely its own thing, a living, growing, decentralized community of humans building a new social network from the bottom up, on the basis of open standards like ActivityPub and free software like Mastodon itself.

mastodon.technology, in spite of the “official-sounding” name, is just one of many instances in the Mastodon network. It is indeed focused on techy/nerdy topics, though of course you can follow people on other instances as usual. There is a code of conduct which is quite sensible, and which is enforced through a shared blocklist. Operations are funded through a Patreon account. The server code is up-to-date.

Right now the operation of the instance very much seems like one person’s passion. The “About” page is short on technical details (backup policy, monitoring, etc.), and most of the tech stuff seems to be sitting on the personal Patreon account. To continue scaling past 10,000 users or so, it may be time to think a bit more about how to grow the administrative side of the community.

(Update: The instance was shut down in late 2022.)

I’m generally a big fan of Kurzgesagt, a channel of animated explanations/explorations of various topics ranging from the Fermi paradox to fracking. But the videos would not be nearly as enticing without the Epic Mountain soundtrack. The music playfully blends piano with 8-bit beeps & boops and the occasional epic theme reminiscent of a Hans Zimmer soundtrack, or even a jazz detour.

I enjoy listening to this music for concentrated work where the goal is to attain a flow state, but also just for its own sake. As with many soundtracks, there are recurring themes in the different Kurzgesagt tracks, but this only enhances the feeling of being transported into a carefully crafted, interconnected soundscape. If you want to listen in, I suggest starting with some of their most popular tracks: Emergence, War, Optimistic Nihilism.

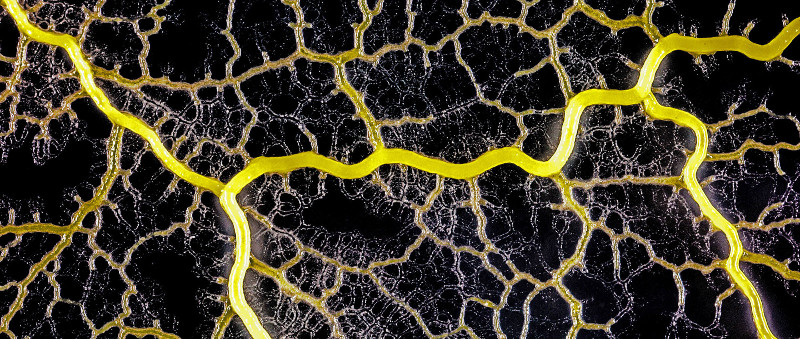

Life at the Edge of Sight by Scott Chimileski and Roberto Kolter is one of those rare books that makes a complex subject — microscopic organisms including bacteria, fungi, protozoans, viruses, phages, archaea — genuinely exciting and wondrous, not by over-simplifying it, but by illuminating it through brilliant photographs and lucid explanations.

You may have seen the authors’ photographic and micrographic work before, for example, in this Quanta article: The Beautiful Intelligence of Bacteria and Other Microbes. If you find the images stunning, the book provides the additional context to understand what’s going on. How and why do bacteria form biofilms, and how do they communicate with each other? What are mycelial networks, and how do they interact with plants? What exactly is a slime mold, anyway, and what makes these brainless creatures so smart?

The slime mold Physarum polycephalum. (Credit: Scott Chimileski and Roberto Kolter. Fair use.)

The book succeeds in conveying a view of the “web of life” that makes humans seem less like a pinnacle and more like one element in an ever-changing, ever-adapting network that transforms our planet both at the smallest and the largest scales. Moreover, life we may consider to be purely microscopic or single-celled often goes through macroscopic or multi-cellular stages.

To drive this point home, the authors include a chart that show the “size ranges” of different organisms, from individuals to collectives. The largest single living organism on Earth may well be a humongous fungus in Oregon— while human spermatozoa exist at the microbial scale.

The Verdict

This is a great book for anyone curious about the smallest dimensions of life. The list price of the hardcover edition as of this writing is $35; you will likely be able to get it for less. That’s a very reasonable price for a gorgeous, 370 page science book that’s also—for the most part—a great read.

If I have one criticism, it’s that the book goes into jargon-heavy explanations early on, which might deter some readers before they have a chance to really dive in. Here’s a quote from page 19:

Archaea, like the gram-positive bacteria, have one cell membrane, but the archael membrane is composed of different lipids than those in the bacterial membrane. Archael cell envelopes often also have an outer crystalline lattice of proteins called an S-layer.

Judging by some of that early writing, you might think the entire book is going to be highly technical, but it isn’t. For example, there’s an extensive description of the microbial life inside a block of cheese; the description is given in the form of an imaginary journey of an explorer who shrinks herself to the microscopic scale and gets into a fight with a cheese mite. In other words, this is a book that allows itself to have a little fun with its explanations.

The bumpy beginning is a minor concern, and I highly recommend this book regardless. If you do pick it up and don’t already have the domain expertise to parse the above quote, don’t give up too quickly; the writing becomes a lot more accessible in later chapters.

More Perfect is an spin-off of the popular Radiolab podcast that specifically focuses on US Supreme Court Decisions, from well-known cases like Citizens United vs. FEC to more obscure but highly consequential cases like Baker v. Carr. In the casual tone typical for Radiolab, each episode brings together many voices on a given case: plaintiffs, legal scholars, historians, activists, and so on. Jad Abumrad, the show’s host, tends to ask flippant questions along the lines of “How does this even make sense?”, channeling a bit of the everyman who knows little about the legal system.

If you’re thinking this premise makes for a dry program, you couldn’t be further from the truth. The court’s decisions have impacted the lives of millions, and the show succeeds in making that impact understandable, from parents fighting to keep their adopted daughter to civil rights activists mourning the loss of voting rights achievements through the landmark Shelby v. Holder case.

I have listened to a handful of episodes so far, and have very much enjoyed them. If I have one criticism, it is that the show can be a bit myopic at times, very much focused on looking at an issue from both sides (e.g., Edward Blum’s test case litigation, which is advancing a conservative agenda through the courts), without providing sufficient societal context: what is the likely impact of this litigation going to be? Who is driving this agenda? Who is benefiting from it? Naturally, some episodes do a better job at this than others.

Still, I recommend the podcast to anyone who cares about the US legal and political context; it provides valuable background about the court cases that made the news, the ones that made the history books, and the ones that didn’t (but should have).