Reviews by Eloquence

Ancient statues and buildings were frequently painted in vivid colors. The modern image of austere white marble is largely an invention, based on misunderstanding the weathered appearance of ancient works as intentional. That invention became the preferred view of antiquity from the Renaissance to today.

Ancient polychromy is not, however, a recent discovery. After all, statues often still had pigments on them when they were discovered (many still do so today). Historians like Johann Winckelmann (1717-1768) acknowledged that many ancient statues were colored, but claimed that “the whiter the body is, the more beautiful it is.”

The true colors of the ancient world reflect the diversity of the people that inhabited it. They also make the ancient West look a lot more like the ancient East, offering a glimpse at the thread that connects all humanity; sharpening the contrast between the polytheistic, messy culture of ancient Rome and the darkening age that followed it.

Since Winckelmann, historians have rarely embraced, sometimes rejected and mostly ignored the true colors of antiquity. In recent decades, a small number of archaeologists and historians have tried to change that, culminating in an exhibition of painted statues called Gods in Color which first opened 2003 and has been continuously updated since then. The book Gods in Color: Polychromy in the Ancient World is a catalog of the exhibition with some additional essays on the subject.

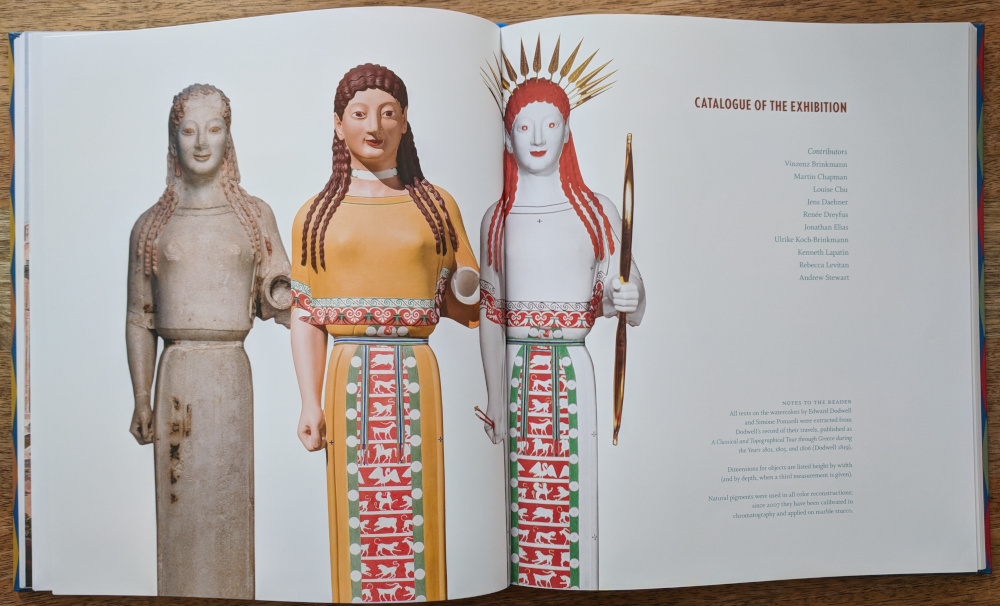

Reconstruction of the Peplos Kore as featured in the book. (Credit: Gods in Color. Fair use.)

The introductory essays are short but interesting, shedding light on the discovery and perception of ancient polychromy, and giving examples of early drawings and reconstructions.

The new reconstructions, however, may offend modern sensibilities. This is less because they’re colorful and more because they just are not very well done. As Margaret Talbot writes in the excellent New Yorker article “The Myth of Whiteness in Classical Sculpture”:

In the nineteen-nineties, [Vincent] Brinkmann and his wife, Ulrike Koch-Brinkmann, who is an art historian and an archeologist, began re-creating Greek and Roman sculptures in plaster, painted with an approximation of their original colors. Palettes were determined by identifying specks of remaining pigment, and by studying “shadows”—minute surface variations that betray the type of paint applied to the stone. The result of this effort was a touring exhibition called “Gods in Color”.

(…)

But [Mark] Abbe, like many scholars I talked to, wasn’t crazy about the reconstructions in “Gods in Color.” He found the hues too flat and opaque, and noted that plaster, which most of the replicas are made from, absorbs paint in a way that marble does not. He was also bothered by the fact that the statues “all look fundamentally the same, whereas styles would have differed enormously.”

All of this is true. Moreover, many of the depicted reconstructions are incomplete, with partially colored eyes or limbs creating a truly garish appearance. Where the original is damaged, so is the replica, with a white broken nose at the center of a flatly painted plaster reconstruction.

The pigments recovered from each original are carefully documented, but the artistic execution of most of the reconstructions is accordingly mechanistic, constrained by evidence that remains between us and the ancient world.

The result is a presentation of antiquity in painted plaster that resembles the uncanny valley of bad computer graphics. The Brinkmanns and their collaborators deserve the world’s credit for forcing us to take a more realistic view of the ancient world in its full color—but a lot of work remains to do so in style.

In November 2015, Nathan Robinson and Oren Nimni launched a Kickstarter to fund the creation of Current Affairs, a print magazine of “political analysis, satire, and entertainment” promising to “make life joyful again”. The campaign exceeded its goal of $10,000. Three years later, Current Affairs has become of the most reliably interesting and, indeed, enjoyable political publications on the left.

Print editions are issued every two months; each is carefully designed and, in addition to articles on diverse topics, every issue contains the creative works of many contributing artists. While many illustrations simply support a given article, in other cases it’s the illustrations that tell the story—see, for example, the “City of Dreams” illustration and accompanying article.

Recent Current Affairs covers. (Credit: Current Affairs. Fair use.)

Chances are that you’ve come across Current Affairs articles before through some of Nathan Robinson’s in-depth “takedown” articles about prominent American and Canadian political writers — especially those spreading reactionary ideas, e.g., Ben Shapiro, Charles Murray, Sam Harris, Jordan Peterson, Mike Cernovich, and Dinesh D’Souza.

Instead of simply dismissing them outright, Robinson takes these figures to account on the basis of their own words, dissecting the ugly mess of hateful nonsense beneath whatever persona they’ve created for themselves.

Current Affairs is a decidedly leftist publication; it routinely condemns capitalist excess, corporate misconduct, “bipartisan” alliances with murderous regimes, the convenient political amnesia concerning America’s history of horrific military interventions, the dark legacy of racism at the root of deep social and economic inequalities.

While it writes of socialism as a political and economic alternative, the magazine has been equally critical of authoritarian socialism. Robinson’s own essay, “How To Be A Socialist Without Being An Apologist For The Atrocities Of Communist Regimes“, puts it quite plainly:

The dominant “communist” tendencies of the 20th century aimed to liberate people, but they offered no actual ethical limits on what you could do in the name of “liberation.” That doesn’t mean liberation is bad, it means ethics are indispensable and that the Marxist disdain for “moralizing” is scary and ominous.

Current Affairs instead leans towards libertarian socialism, an ideology seeking to balance a high commitment to individual freedom with a concern for the welfare of societies. It speaks of “humanistic” values and holds all ideologies to account for living up to those values.

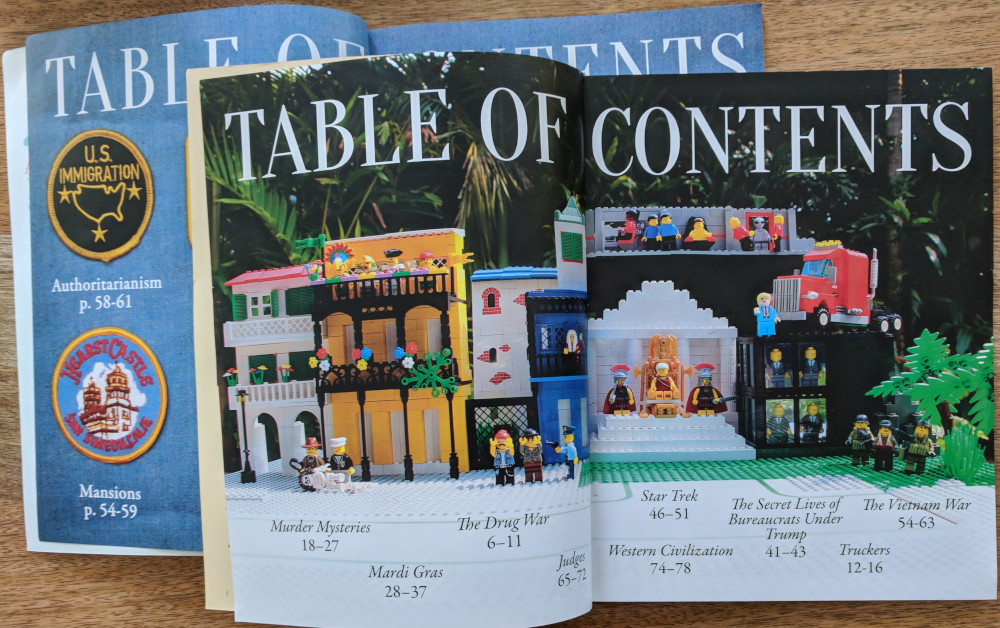

The magazine publishes essays about diverse topics from the changing politics of Star Trek to the Mardi Gras holiday in New Orleans. You’re in for a visual treat the moment you open the table of contents, each of which is an artistic exploration of the topics covered in the current edition.

Current Affairs table of contents examples. (Credit: Current Affairs. Fair use.)

Alongside its playfulness and occasional silliness, the magazine features articles such as a gut-wrenching and unflinching look back at the Vietnam War (“What We Did”) or an insightful report on disillusioned African-American Rust Belt voters (“The Color of Economic Anxiety”).

Recently, the magazine also launched a podcast; as of this writing, it is already generating more than $6,000/month in Patreon support (supporters get access to bonus episodes). The podcast features conversations between the magazine’s contributors on a wide variety of topics, featuring segments like “Lefty Shark-Tank” (tongue-in-cheek criticism of left-wing policy ideas), interviews, answers to listeners, parody ads, and more.

Legally, Current Affairs is not a nonprofit; Nathan Robinson told me by email that the team “debated it and then decided against it as it creates all kinds of logistical headaches”.

However, he emphasized that Current Affairs will never operate as a for-profit company. Over the course of each magazine’s two-month run, all articles are published online without any kind of paywall, and the website and magazine are entirely free of third party ads. Regrettably, articles are under conventional copyright, as opposed to a permissive Creative Commons license.

Article example from the latest issue. (Credit: Current Affairs. Fair use.)

The Verdict

After reading their online edition for a while, I subscribed to Current Affairs earlier this year, and have not regretted it yet. At $60 for 6 issues, you get good value for your money; the magazine is a pleasure to look at, and I generally read it all the way through before the next one arrives.

A few typos usually slip through, and some articles would benefit from more rigor (data, citations) or additional editing. But these are the kinds of problems you would expect from a small, independent magazine.

In many ways, I prefer the Current Affairs model to the heavily grant-funded nonprofit publications I’ve reviewed (e.g., The Marshall Project, ProPublica). It will likely never be able to muster the resources to engage in a similar scale of reporting projects, but its writing is fearless and independent, funded entirely by readers. While its humor can be snarky, underneath it there’s an earnestness that’s disarming and likable. I highly recommend checking it out.

Would you enjoy reading it? Fortunately, that’s easy to find out by browsing the archives of the website. Regardless of its legal status, I’ve also added it to the Twitter feed of quality nonprofit media, which is a convenient way to sample the content of many nonprofit outlets if you happen to use Twitter.

In 1971, Daniel Ellsberg leaked the Pentagon Papers to 19 newspapers. Comprising 7,000 pages, they are an internal history of the Vietnam War compiled by the US government. By doing so, Ellsberg made himself a target of the Nixon administration. The first operation of Nixon’s infamous “White House Plumbers” was the burglary of the offices of Ellsberg’s psychiatrist in order to find materials that could be used to discredit him. Later, members of the group would break into the Watergate hotel, bringing down Nixon’s presidency.

Secrets, first published in 2002, is Ellsberg’s memoir. It focuses on his work for the RAND Corporation and the Pentagon, including the time Ellsberg spent in South Vietnam, and the influences on his thinking that ultimately moved him to become a whistleblower.

A Harvard-educated intellectual, Ellsberg was quickly drawn into the upper echelon of US policymaking. In the early part of his memoir, he describes how, at the Pentagon, secrecy was used not just to conceal information from the public, but also to wage turf wars between departments, with new classifications being invented just to prevent rivals from seeing a certain memo or document.

He is not shy to admit the seductive and addictive nature of access to secrets, and how it breeds contempt from political insiders for the outside world. The public, after all, never knows the true reasons why a political decision was made, so how could the judgment of any member of the public be trusted? Lying to the public in official statements is so common that when lies are used to justify war — as was the case after the Gulf of Tonkin incident — it hardly seems notable to those on the inside.

From skeptic to cynic, from cynic to activist

Yet, Ellsberg was not a critic of this system at the time; he was a willing participant. When he was offered his role at the Pentagon with a specific focus on Vietnam policy, he was at first reluctant not because he questioned US motives in the war — as a Cold Warrior, he shared a desire to limit the spread of communist influence — but because he was skeptical that the war was winnable.

During his two years in South Vietnam, Ellsberg’s skepticism turned into cynicism, as he observed how, with all the unspeakable brutality of the war, there was no strategy or tactic that promised real gains against North Vietnam, short of the total destruction of the country. Moreover, forces on the ground even fabricated entire operations to pretend that “pacification” was around the corner at any moment.

Upon his return to the US, Ellsberg struggled to understand how successive presidencies could push forward a war that was going nowhere and costing hundreds of thousands of lives. Had these presidents simply been victims of their own propaganda? To find out, he participated in the creation of the report known as the Pentagon Papers. And it was his inside knowledge of the report, combined with his exposure to the peace movement, that ultimately caused him to become a whistleblower.

The Pentagon Papers showed that, far from cluelessly bumbling into war, the United States had recklessly escalated a war of aggression against a country that, to begin with, had sought independence from a colonial power, much as America had once done. But here, America had chosen the side of the colonizers.

Presidents Eisenhower, Kennedy and Johnson had willingly signed off on escalation after escalation, even as advisers were telling them that far greater efforts were needed to “win” the war. And it was the Nixon administration that would take the war to levels that can only be described as state terrorism, as Nixon himself promised privately: “We are not going to let this country be defeated by this little shit-ass country.” And he made it clear to Henry Kissinger: “You’re so goddamned concerned about the civilians—and I don’t give a damn. I don’t care.”

While Ellsberg would only learn about these statements when the Nixon White House tapes became public, he did know from insiders that Nixon was lying about pursuing peace in Vietnam, and that he was instead prepared to again escalate the war’s brutality in hopes of forcing North Vietnam to “negotiate” with the United States.

This threat of escalation motivated Ellsberg to try various venues to get the Pentagon Papers out, ultimately releasing them to many newspapers as a dramatic man-hunt against him got underway. The Pentagon Papers didn’t cover the Nixon period, and they mostly reflected poorly on previous Democratic administrations. Nevertheless, Ellsberg felt that making visible how administration after administration had made the same mistakes in Vietnam — and lied about it to the public — would at least help hold Nixon to account.

Nixon, for his part, privately welcomed the leak. It was only when he feared that Ellsberg had more material pertinent to his administration that he fully escalated an effort to silence Ellsberg. Aside from the break-in at his psychiatrist’s office, the Plumbers planned a physical attack against Ellsberg at a rally. In his own autobiography, Gordon Liddy confessed that the Plumbers even considered lacing Ellsberg’s soup with LSD before a public speech, to make him appear like a nutjob.

This criminal campaign failed, and as it was exposed, so did the indictment against Daniel Ellsberg. To this day, Ellsberg remains an outspoken activist against war and secrecy, and in defense of whistleblowers like himself.

The verdict

Secrets is an essential account of how secrecy can turn a republic into an empire, at least where foreign policy and “national security” are concerned. As a book about the Vietnam War, it cannot begin to scratch the surface of the horrors inflicted upon the Vietnamese. But to understand how we can prevent history from repeating itself — how we can undermine the secrecy machine by supporting whistleblowers, and how we must demand transparency whenever our government kills on our behalf — Secrets is as timely and necessary as ever.

Disclosure: I work for Freedom of the Press Foundation, where Ellsberg is a Board member.

As of this writing, James C. Scott is 81 years old. Best known for Seeing Like a State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed (reviews), he is an accomplished scholar of non-state societies. Near the end of his career, Scott is not pulling any punches. Against the Grain seeks to dismantle the standard civilizational narrative — that early state-based agricultural societies were part of a linear progression towards civilization as we understand it today.

Scott demonstrates that the hunter-gatherer lifestyle that preceded sedentary agriculture was egalitarian, relatively peaceful, and allowed for significant leisure time, and that early human cultures combined a variety of approaches to survive. Beyond hunting and gathering, these included shifting agriculture, pastoralism (raising livestock and moving the herd in search of new pastures), and even sedentary agriculture, well before the emergence of states.

Our ancestors were opportunistic and looked for the quickest way to make a living. Agriculture wasn’t necessarily a response to population pressure — depending on the environment, it just offered a more reliable return than hunting and gathering.

In Scott’s narrative, the creation of what he calls “late-Neolithic multi-species resettlement camps” — settlements where humans, livestock, other domesticated animals like dogs, and domesticated plants lived together for extended periods of time — caused never before seen levels of drudgery and misery. The high population concentration led to disease and crop failures, and agricultural cultivation created tedium and reduced cultural complexity.

But it also created opportunities for those who accumulated power to attempt to preserve it. The settlements could be strengthened by abducting and enslaving nomads or members of other communities. By standardizing on cereal grains — “visible, divisible, assessable, storable, transportable, and ‘rationable’” — early states were able to sustain their bureaucracies (and increase elite wealth) through taxation.

A polemic against civilization

War and slavery were not inventions of the state, Scott acknowledges, but it is only through the concentrated power of early states that they could they be brought to a previously unseen scale. When state societies collapsed, many of the enslaved or coerced members (if they survived—a big “if” Scott glosses over a bit too readily) were better off. And state collapse occurred frequently, due to disease, war, starvation, rebellion, and other causes.

Meanwhile, the “barbarians” who did not join state-based societies (and who could not easily be captured because of where they lived) became more sophisticated, extracting tribute from the state — but also selling each other out to serve as mercenaries for hire.

Where Scott’s writing turns into polemic is when he dismisses the idea of “dark ages” (such as the Greek Dark Age or, though he barely writes about it, the period following the collapse of the Roman Empire). The fact that we don’t find monumental buildings, wall paintings, or a strong written tradition, he reminds us, doesn’t mean nothing of interest happened — after all (a point Scott repeats), Homer’s great epic was composed during a “dark age” and transmitted orally.

Scott persuasively marshals the evidence that concentration caused many new hardships, and led to societies which were frequently (if not always) deeply unjust. But he does not attempt to examine the arguments against dispersal, or for large numbers of humans living with each other in close proximity, sharing ideas and beliefs at a pace previously unimagined.

He dismisses “elite displays” such as monuments and temples, but does not write about roads, aqueducts, libraries, poverty relief such as the Cura Annonae, or any legitimate effort to better the life of a community’s members, if such life was organized partially through a state.

Indeed, the word “science” does not appear in the book’s index. Human progression that is the result of better understanding our world and applying that knowledge is too readily dismissed in an effort to keep the book true to its title.

Here, Scott’s book — so critical of ideological views of “civilization” — is itself ideologically committed to rejecting an evidence-based view. “But what of the slaves?” one can imagine Scott saying. “But what of the elites, enriching themselves?” Yes, but what of Euclid, Democritus, Ovid? What of the Library of Alexandria, or the Antikythera mechanism, or the art of Pompeii? What of the religious extremism that followed Rome’s collapse, and probably followed earlier collapses as well?

The verdict

Scott uses language not to obfuscate, but occasionally in ways I would describe as performative. Against the Grain makes frequent use of technical terms from agriculture and anthropology; the writing is dry (though suffused with a dark academic humor) and sometimes repetitive. What keeps the book interesting is its challenge to orthodoxies and its willingness to put things plainly when required, e.g., when writing about slavery.

Against the Grain does re-cast our understanding of history. Scott is correct to critique those who want to see linear progression in human history; a rise from savagery. Deep history that looks at the distant past of our species is crucial to get a clear picture of how we became who we are. Our hunter-gatherer ancestors were far from stupid, and their minds were far from simplistic compared to our own, nor were their lives especially brutal or difficult.

History cannot be understood without examining the accumulation of power and resources, all too often including slaves and other coerced labor. If we want to build morally just societies, we must understand how this accumulation of power is at odds with moral progress, even as it has often enabled scientific or technological progress.

But here ends the usefulness of Scott’s book. The fact that his work celebrates the dispersed life beyond the reach of the state is perhaps precisely why his colleagues can celebrate him as an anarchist academic. His writing poses no threat to real systems of power, because it offers no alternative. It is an important read, but only as a starting point for developing a more nuanced understanding of the human story, correcting misconceptions in the common narrative still taught in schools. In the final analysis, Scott is a rebel without a cause.

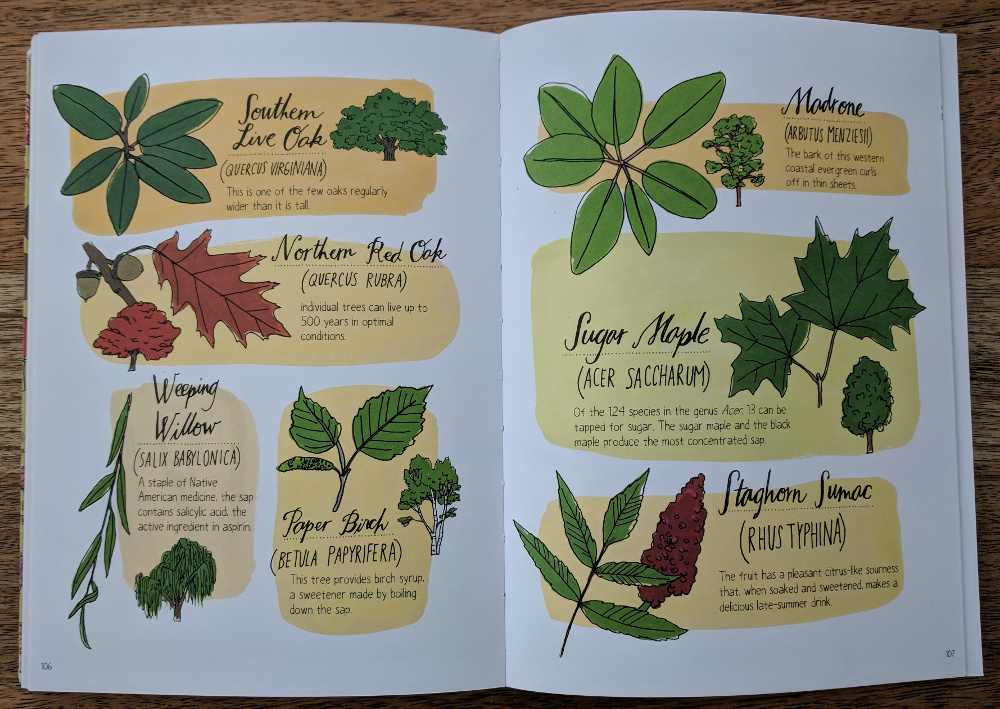

Julia Rothman is an illustrator from New York; in Nature Anatomy: The Curious Parts & Pieces of the Natural World she expresses her love of nature through 223 pages filled with colorful sketches, brief explanations and descriptions.

The art is simple but elegant, conveying the most recognizable characteristics of a leaf, a mushroom or a butterfly in just a few strokes. The organization varies from page to page:

-

annotated illustrations (“anatomy of a flower”) with brief explanations;

-

illustrations without any text or explanation other than a species name;

-

illustrations with brief facts about a species (“Woodchuck: Woodchucks can climb trees if they need to escape”)

-

recipes and other offbeat material, e.g., instructions for printing plant patterns.

This kind of presentation is fairly typical for the book: elegant illustrations accompanied by one or two facts. (Credit: Julia Rothman. Fair use.)

Of course, the book can only sample the natural world (and it does so with a North American bias), but it does attempt to provide some broader explanations as well, e.g., about moon phases or the layers of Earth’s atmosphere.

Some of the text is in cursive, giving the book the feel of an intimate journal. That’s clearly the idea: making the complexity of nature less intimidating by focusing on its beauty and by conveying descriptions and explanations in a casual manner.

At the same time, this approach can no more than whet the appetite for more detailed explanations why nature is the way it is (for which speaking about evolution, which this book hardly does, is essential).

Is this approach suitable for getting young people excited about the natural world? I’m no longer a young reader, but if I was, I bet I would have been in equal parts frustrated and pulled in by this book; pulled in by its art, and frustrated by its failure to go beyond enumerating names and facts. I would give the book 5 stars for art and 3 stars for the text—a good purchase for extending one’s appreciation of the patterns of nature, if not necessarily for understanding them.

The Lion’s Song is an episodic cross-platform video game set in and near Vienna shortly before the First World War. The game features pixel art in a six color sepia palette, which gives it a unique look and feel.

While the game mechanics resemble point-and-click adventure games, this is more of an interactive story. There is no inventory; choices and decisions largely take the place of puzzles.

Each of the four episodes only has about 30 minutes of play time, but the game encourages you to revisit past decisions and explore the connections between the lead characters of each episode (all fictional):

-

Wilma Dörfl, a composer of humble origins who is trying to finish a pivotal piece that could make or break her career, while figuring out her relationship with her mentor;

-

Franz Markert, a painter who is making his debut in Gustav Klimt’s art salon, and who can see “layers” in the personalities of the people around him, while being unable to see them in himself;

-

Emma Recniczek, a mathematician who is looking for guidance from Vienna’s “Radius” (a circle of mathematicians who meet regularly in the backroom of a cafe), but who faces rejection because she is a woman;

-

Albert, the son of a baron who wanted to become a journalist, but finds himself forced to start a military career; during a train journey he meets people who are connected to each of the three characters above.

Franz Markert (second from left) in the art salon (Credit: Mipumi Games GmbH. Fair use.)

The second and third episode have the most depth. It’s fun to be Markert and visit Vienna’s street vendors or the art salon, observing little ghost figures (the “layers” he sees in people’s personalities) appear behind other characters as you walk by them. You get to choose which character you want to paint, which contributes a lot to the replay value of this episode.

Playing Emma, you face important choices regarding your identity and how you present yourself to others, as you try to overcome the societal obstacles to your career as a female mathematician developing a new “theory of change”. Along the way, you briefly meet Markert in a cafe, who is always on the lookout for interesting people to paint.

The sounds and music of the game—the storm and rain outside Wilma’s cabin; the sound of horses in the streets of Vienna; the chatter of the salon—give the game an immersive quality that you might not expect from looking at its low-resolution graphics. The composition which gives the game its title—the Lion’s Song which Wilma composes in the first episode—plays a role similar to the Cloud Atlas composition in David Mitchell’s book of the same name, connecting the threads of story through a tapestry of beautiful music.

Some elements of the story are a bit forced (the confrontation between mathematicians in front of a class of unruly students comes to mind), but for the most part, you become invested in the characters and their fates. The decisions you make truly do have ripple effects throughout the episodes, from the exact composition of the music to the paintings that appear on the walls and the epilogue of the game. Even marginal aspects of the game—credits screens, the “connections” section—are lovingly designed interactive rooms.

You’re unlikely to get more than an evening or two of enjoyment out of this brief game, but the gorgeous art and music, the attention to detail, and the fascinating setting and characters make it unlikely that anyone who enjoys interactive stories would regret this purchase (as of this writing, $10 at GOG).

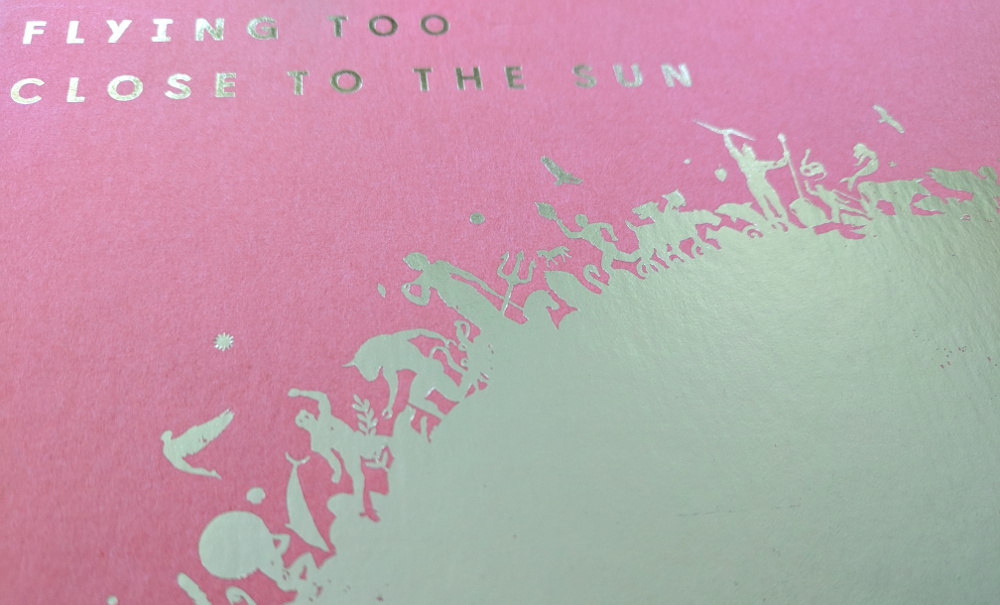

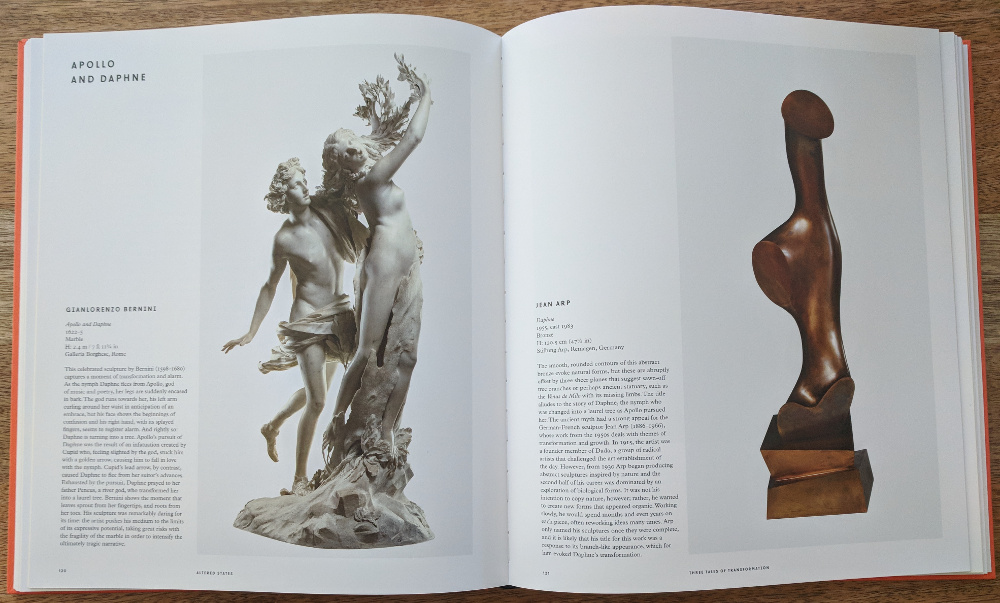

Flying Too Close to the Sun is a large format art-book from Phaidon that examines the influence of classical (Greco-Roman) myths on artistic expression since ancient Greece, for example:

-

the story of Daedalus and Icarus, which inspired the book’s title;

-

the story of Apollo and Daphne: Daphne escapes the lovestruck Apollo by begging a river god to transform her into a tree;

-

the story of the minotaur and of his slayer, Theseus, the founding hero of Athens.

The book features direct artistic references to these stories, from Greek vases to Renaissance paintings and contemporary sculptures. It also includes some modern art that may or may not intentionally reference classical mythology, but that shows some parallels in theme or expression.

Book cover (partial view). The "flares” of the sun include references to the myths explored in the book. (Credit: Phaidon Press. Fair use.)

At 250 x 290 mm (11 3/8 x 9 7/8 in), the book’s format gives these works of art the space they deserve. The captions are clear and often briefly retell the myth that is being discussed. That makes for some repetition in a single reading, but it also makes it easy to open the book at any page without requiring additional context.

As with any art book like this one, it’s possible to quibble about the works that were chosen or overlooked. For example, it will probably take another generation until editors choose to include art from games like Apotheon, a gorgeous indie platformer that brings the artistic style of ancient Greek pottery to life—to say nothing of the ubiquitous references to mythology in big-budget entertainment like God of War.

Apollo and Daphne (1622-25, Bernini) side-by-side with Jean Arp’s Daphné (1955). (Credit: Phaidon Press. Fair use.)

To me, this speaks to the still austere relationship we have with classical myths. In fact, ancient art was colorful, often lewd, and a form of mass entertainment. It provided common reference points in everyday life, it served propaganda purposes, it blended belief with pure pleasure.

While Flying Too Close to the Sun only hints at this, it is a joy to page through the high quality reproductions and photographs, to explore the content of complex paintings with helpful captions, and to become more familiar with the details of these myths. Recommended.

Before Ed Snowden and Chelsea Manning, there was Daniel Ellsberg, a military analyst who leaked the Pentagon Papers to 19 newspapers in order to inform the American public about the true nature of the Vietnam war. Ellsberg became a committed anti-war activist, but early in his career he was a devoted Cold Warrior. As a strategic analyst for the RAND Corporation, he reviewed and helped shape America’s policy for thermonuclear warfare.

The Doomsday Machine: Confessions of a Nuclear War Planner are Ellsberg’s recollections of this work, combined with a summary of what’s become known about the highly secretive nuclear war plans of the United States and the Soviet Union since then—and how those plans fared in reality during times of crisis. He argues that we have created a Strangelovian doomsday machine which remains on hair-trigger alert, and that the primary goal of nuclear policy at this point should be to dismantle that machine.

Ellsberg documents how close humanity came to self-destruction during the Cold War, and also shows convincingly how the threat of first use remains a key element of US foreign policy, with enemies old and new. This barbaric idea—that it is perfectly reasonable to threaten first use of nuclear warfare as an “option on the table”—must surely die before true progress toward global nuclear disarmament can be made.

How and why did rational people who loved their families and wanted peace for their children participate in planning for global annihilation? Ellsberg provides a brief history lesson on how war planners during World War II embraced with increasing enthusiasm the idea of “strategic bombing”, a euphemism for murdering and maiming large numbers of civilians—men, women and children—in order to “demoralize” an enemy, culminating in the firebombing of Tokyo.

“My Child” by Miyamoto Kenzo, a survivor of the firebombing of Tokyo (Credit: Miyamoto Kenzo. Fair use.)

“It was an ocean of fire. My mother held my hand as we entered the chaotic stream of refugees and headed for the Arakawa embankment. This painting is of something I saw on the way and have never been able to forget. A pregnant woman was standing there like a ghost; at her feet was a child of perhaps three or four years. The child wasn’t moving at all. The way they were lit up by the flames around them—it was a sight I saw at twelve that was so horrifying I’ll never be able to forget it.” — Miyamoto Kenzo, who was 12 at the time of the Tokyo raid. (Source)

This mass murder was rationalized in simple terms: it was said to shorten the war and minimize American casualties. In this context, the idea of using atom bombs was seen as mainly a step up in efficiency, not a fundamental shift in policy. And individuals like Curtis LeMay, who led the firebombing campaign—far from facing charges—would be put in charge of key military and civilian functions as America built up its nuclear arsenal.

The Verdict

Ellsberg’s book is lucid, personal and informative, and his warnings are timely in an America led by a self-described madman who threatens nuclear annihilation of North Korea one day, then brokers theatrical peace talks the next. Some readers will be put off by the heavy use of military acronyms—they’re enumerated in a bare-bones glossary, but often get in the way while reading. There are no photographs, tables or illustrations, but Ellsberg cites his sources extensively, many of which are online.

Countless books have been written about the folly of nuclear weapons, and about the imminent threat to human existence that they continue to pose. Some are more emotionally persuasive than The Doomsday Machine, others provide more complete historical context. Certainly Ellsberg’s level of access during his time as a military analyst gives him an unusual and compelling vantage point. But what this book does exceptionally well is to demonstrate that the dangers of nuclear warfare are not contingent on monstrous individuals being in charge.

Even with better leaders than the ones we have today, these weapons should not exist because they cannot be controlled. With the leaders we have, eliminating them is a moral emergency.

Disclosure: I work for Freedom of the Press Foundation, where Ellsberg is a Board member.

In Humanizing the Economy: Co-operatives in the Age of Capital, John Restakis, a veteran of the Canadian co-op movement, argues for increasing the role of co-operatives and economic democracy, without suggesting that they are a panacea.

Restakis’ argument is firmly grounded in a critique of corporate capitalism; the 2007-2008 financial crisis still loomed very large when the book was published. But Restakis is also highly critical of the disastrous and dehumanizing effects of authoritarian systems with centralized, planned economies.

Instead, much of the book comprises case studies of co-operative economics:

-

the region of Emilia-Romagna in Northeast Italy, where thousands of co-operatives thrive and nearly two out of three citizens are members of co-ops;

-

the fábricas recuperadas (recovered factory) movement in Argentina, a system of co-operative self-management of factories which followed the country’s economic crisis in 2001;

-

the sex worker collectives in India, such as Durbar, a collective of over 65,000 sex workers that combines mutual aid and social services to its members with political advocacy;

-

the Japanese system of consumer co-operatives with more than 28 million members, which provide services such as home delivery, while also incorporating ethical sourcing practices and promoting organic produce;

-

the global movement for fair trade and its sometimes rocky relationship with the co-operative approach.

Unless you’re steeped in the history of co-operatives, it’s quite likely that you’ll find remarkable examples you’ve never heard of. It’s rare for the narrative in conventional Western media to look at examples like these; when there is reporting about economic matters, it’s mostly about whether this or that elected leader will be “business-friendly” and “convince the markets”.

Restakis challenges this thinking about markets as an implacable, amoral force of nature and instead argues that markets are what we make them. An economy that places shared human concerns at its center (and that de-emphasizes the profit motive and the advancement of the individual) is not only possible—it’s one that hundreds of millions of people already participate in.

Members of the Durbar collective of sex workers march against violence and trafficking in Kolkata in 2018. Durbar provides services to sex workers, fights for legalization of sex work, and combats human rights violaitons. (Credit: India Blooms. Fair use.)

Ideas Vs. Ideology

The ideology of corporate capitalism is just that: an ideology that is taught in schools and universities, in media depictions of success and failure, in its self-advertisements. Corporate capitalism also enjoys massive subsidies, including the planet-wide subsidy of tolerating the destruction of the environment instead of taxing it.

Restakis notes that governments have a choice: to continue to underwrite this ideology without question—or to shift resources towards promoting co-operative economics. This kind of support can range from teaching how to run a business co-operatively, to establishing tax incentives, to setting up resource centers (as was done in Emilia Romagna) that provide administrative support to help co-ops succeed.

It’s not as distant a possibility as it may seem. For example, Jeremy Corbyn’s political platform combines nationalization in some areas of the economy with heavy support for the co-op model and workplace democracy in others.

The Verdict

Restakis frontloads his most radical criticisms of corporate capitalism to the early chapters of his book. Humanizing the Economy is a case for incorporating the co-operative model into economic thinking, without offering a blueprint how to do that, or even suggesting that it should be the dominant model of the economy.

For the most part, the author succeeds in making this argument. Given that the book significantly relies on data (numbers of factories recovered in Argentina; numbers of employees in the co-operative sectors of Italy, Spain or Japan; success of credit unions during the financial crisis, etc.), it is disappointing that there is not a single chart or table in the book.

For a book written in 2010, I would also have appreciated more insights into how the Internet enables new forms of cooperation and sharing. Fortunately, other authors have since filled this void, such as Trebor Scholz and Nathan Schneider with “Ours to Hack and to Own: The Rise of Platform Cooperativism”.

As someone still learning about co-operative practices and the solidarity economy, I found John Restakis’ book a useful wayfinder to a lot of examples that I will likely keep coming back to. If you are looking for similar inspiration, I recommend this book.

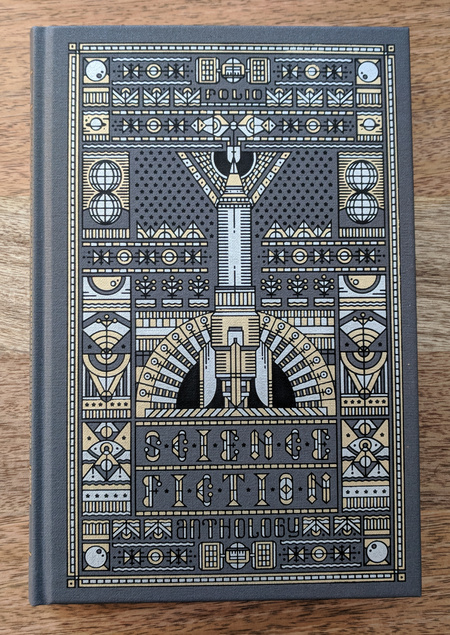

Many sci-fi readers will recognize the name Brian Aldiss (1925–2017), both from his own stories and novels, and from the many anthologies he compiled. The first, for Penguin Science Fiction, was published in 1961. This one is the last, and it is also Aldiss’ final published work. It was published by the Folio Society, which specializes in expensive but beautiful editions of many classic and contemporary works, and which also publishes original anthologies such as this one.

The packaging

You won’t find this book on Amazon, and it is currently advertised at USD 53.95—a hefty price for a single volume. But that’s the Folio way—these are books for bibliophiles, whether that describes yourself or someone you care about. The cover, in this case, is block printed on buckram (cloth) and features a beautiful abstract illustration of a rocketship:

Cover for the Folio Society Science Fiction Anthology (Credit: Folio Society / own photograph. Fair use.)

It’s a pleasure to hold this book and to examine the detail of the print:

Detail of Folio Society Science Fiction Anthology book cover (Credit: Folio Society / own photograph. Fair use.)

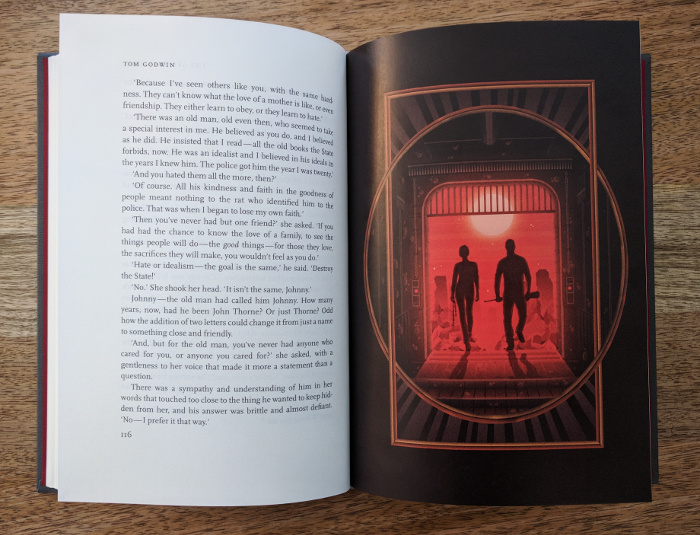

The book comes with a slipcase cover, which looks more stylish than a typical dust cover, and doesn’t get in the way while reading. Like many Folio books, the anthology features commissioned illustrations for several of the stories in the anthology:

Pages from Folio Society Science Fiction Anthology. (Credit: Folio Society. Fair use.)

The stories

The stories are arranged in chronological order. They are:

-

Micromégas by Voltaire (1752)

-

The Star by H.G. Wells (1897)

-

Bridle and Saddle by Isaac Asimov (1942)

-

The Greater Thing by Tom Godwin (1954)

-

Grandpa by James H. Schmitz (1955)

-

Poor Little Warrior! by Brian Aldiss (1959)

-

Recall Mechanism by Philip K. Dick (1959)

-

An Alien Agony by Harry Harrison (1962)

-

Searchlight by Robert Heinlein (1962)

-

Clarita by Anna Kavan (1970)

-

And I Awoke and Found Me Here on the Cold Hill’s Side by James Tiptree Jr., pen name of Alice Sheldon (1972)

-

The Day They Raised the Titanic by Alice Wilson (2015)

As is evident from this list, there is only one recent story, and many are from around the Golden Age of sci-fi—don’t expect to find tales of posthuman existence or hard sci-fi grounded in our current knowledge of space travel and planetary exploration. That said, I found several of the stories quite stimulating:

-

Bridle and Saddle—this story is part of Asimov’s Foundation saga, but requires no familiarity with it. The administrator of a lightly populated planet that exercises centralized control over all knowledge on behalf of a multi-planetary society is faced with threats from the planet’s powerful neighbors, and from discontents at home. Will he be able to hold onto power without violence, which he calls “the last refuge of the incompetent”?

-

Grandpa—a kid who is part of a colonization team stewards a small expedition on a large lily-pad-shaped hybrid plant/animal called “Grandpa”. Grandpa, it turns out, is not quite as simplistic a creature as everyone thought, and our protagonist has to find a way out of an increasingly desperate situation. Although more than 60 years old, there’s nothing in this story that dates it to its era.

-

An Alien Agony—science and religion clash on a planet that has very little experience with either. A beautiful little “loss of innocence” story.

-

And I Awoke and Found Me Here on the Cold Hill’s Side—this story caught me by surprise in that I’ve never encountered its premise before: that humans are uniquely attracted to aliens (both sexually and in terms of pure curiosity), while other species find this behavior very amusing. A story that explores xenophobia and xenophilia, and makes you think about what alien encounters would actually be like.

The illustrations by Florian Schommer stylistically follow the books’s chronology (“as the stories move towards the modern age a palette of deep oranges and reds is gradually introduced”, to quote Folio’s description), and the polygons and circles that frame each picture make them look like windows into different worlds.

The Verdict

I quite enjoyed about half the stories in the volume, and some of them (like Grandpa) are true gems of the genre. As with every Folio Society book I have the pleasure to own, this is a beautifully made physical object. It is also a lovely gift for any sci-fi lover. 3.5 stars, rounded up because of the appreciation of the book as an object that endures in Folio’s publications.