Reviews by Eloquence

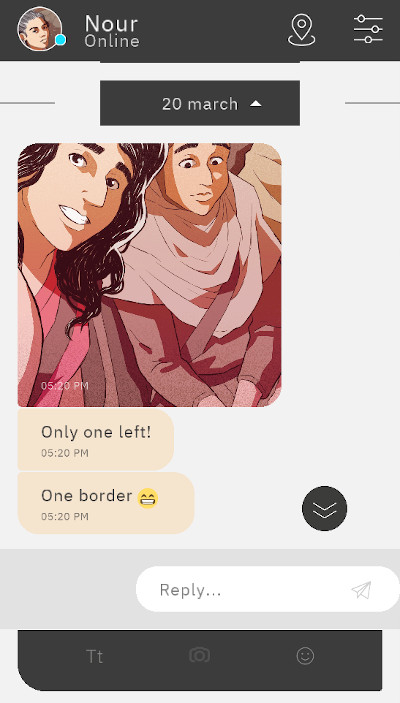

Bury Me, My Love is a choice-driven visual novel about the refugee crisis that has resulted from the Syrian Civil War. It is told in the form of text messages exchanged between a young woman, Nour, and her husband, Majd. Nour is trying to make her way to Europe, while Majd is forced to remain behind to take care of older family members.

According to the game’s website, the editorial team of the project includes the author of the Le Monde feature “Dans le téléphone d’une migrante syrienne” (“On the phone of a Syrian migrant”) and one of the migrant women portrayed in that story. While the game is not biographical, it attempts to present a realistic composite informed by real experiences.

Messages from your wife

You play as Majd. You click to advance the story, but you also have to make a significant number of choices throughout. Nour asks for your advice on everything—what mode of transportation she should use, where she should stash her cash, what kind of smuggler to trust, which countries to travel to.

The game has many endings, not all of them positive; when you are finished, you can review Nour’s journey on a map.

As the player, you experience Nour’s arduous journey through her husband’s phone. (Credit: The Pixel Hunt, Figs and ARTE France. Fair use.)

The intention is clearly to humanize a crisis of unimaginable proportions. By experiencing Nour’s journey through a series of WhatsApp messages, we are invited to relate it to our own experiences. As developer Florent Maurin described his reaction to the Le Monde feature (which heavily relied on the text message format):

“It was really powerful as it felt very familiar to me and how I use WhatsApp to chat with my friends and family, sending emojis, jokes and pictures. But it was also very odd because they were discussing matters of life and death.”

Clearly, Bury Me, My Love attempts to replicate these sensations: familiarity, shock, confusion. And it often succeeds at building on the reading experience—waiting to hear from Nour can be genuinely nerve-wrecking. If you don’t mind spoilers, Florent Maurin’s GDC presentation gives some insights into the design philosophy and ethics behind the game.

Nightmarish choices

But the game is disconcerting in other ways in which a newspaper article is not. As the player, you are asked to make choices which may lead Nour to safety. But that can be seen as putting the impetus on refugees to make the “right” choices, rather than on governments.

You exclusively play as Majd, and all branching paths are the result of his messages. In spite of the best efforts of the developers, I felt that Nour was underdeveloped as a character, and would have liked to see the journey through her eyes. I would have also appreciated additional context, such as newspaper clippings from the time.

It took me about a couple of hours to play the game. Nour made it to safety in my first playthrough. The game suggested that I try other paths, but that seemed almost like an appeal to sadism, considering that some of these choices may well lead to Nour’s death.

While the game was included in itch.io’s massive Bundle for Palestinian Aid, it’s ordinarily sold as a commercial title ($5 on Steam), and proceeds do not go to any charitable cause. I played the game on Linux through Proton without issues.

The Verdict

Bury Me, My Love attempts to do something very important—to help us empathize with experiences that news reports usually keep at a comfortable distance. It ultimately falls short of this ambition, both because it is too much like a game (centering player choices) and not enough like one (restricting our perspective to Majd’s mobile phone). 3.5 stars, rounded down.

Highway Blossoms is a romantic visual novel about two young women (Amber and Marina) who meet through a chance encounter on the side of the road, and soon embark on an adventure together. It is a 4-6 hour long story told in text, pictures, animations, music, sound and voice. As the player, you don’t get to make any choices—your influence ends on the settings screen.

The story is told in the first person from the perspective of Amber, who is on a road trip in her grandfather’s RV. Her grandfather, who played a central role in Amber’s life, has recently passed away, and the trip is Amber’s way to process the loss. In this healing journey, she is aided by a bucket full of cassette tapes that she and “gramps” used to listen to.

On the side of the road in New Mexico, Amber first spots Marina, whose car appears to have broken down, and offers her assistance. It turns out that Marina is bubbly, cheerful, and entirely unprepared for her first trip away from home.

Soon enough, Marina draws a reluctant Amber into the purpose of her own trip: a treasure hunt across multiple states, based on claims in an old journal ostensibly written by a gold rush era miner.

Amber and Marina in Vegas. These are the two sprites (with different facial expressions, poses and gestures) used through most of the game. (Credit: Studio Élan. Fair use.)

Amber and Marina grow closer during their adventure, and their blossoming love is the fluttering heart of the story. They do encounter other characters, chief among them a trio of treasure hunters led by a fierce and obnoxious woman named Mariah.

Tropes in America

In many ways, it feels more apt to compare Highway Blossoms with a romantic comedy movie than with a novel. The characterizations are over-the-top (Marina is the ditzy but angelic love interest sometimes found in rom-coms), and the presentation heavily relies on the capable voice acting by Katie Dagnen (Amber) and Jill Harris (Marina).

It’s all very cheesy, but it works, and you quickly forget that you’re not at the wheel at any point during this trip. The story features many notable sites—e.g., Shiprock, Canyon de Chelly, Arches National Park—which may inspire some players to make real world travel plans. The treasure hunt that motivates several of the stops gives parts of the story an unfortunate colonialist undertone.

The game features two erotic scenes between the main characters, which can be downloaded from the game’s website and added to censored editions. The scenes are part of the story and their inclusion feels neither forced nor gratuitous. In addition, the game includes extras such as “Marina’s Thoughts”, a gallery of small mementos from the story with Marina’s written comments on them.

The Verdict

While I found the graphics and parts of the soundtrack a bit repetitive, and some of the writing a bit cringey, I would overall recommend the experience if you’re in the mood for a wholesome love story. I would give Highway Blossoms 3.5 stars—rounded up because it made me both cry and laugh, as any romantic comedy should. There’s a continuation of the story called “Next Exit”, which I look forward to playing in future.

Iris and the Giant falls into the genre of roguelike deck-building games, in which you collect and use playing cards to engage in combat. You play as Iris, a young girl who is seeking respite from bullying and depression in a fantasy world loosely inspired by Greek mythology.

In isometric dungeons rendered in a minimalist but stylish vector art style, you face wave after wave of enemies in turn-based battle: from skeleton warriors to axe-wielding minotaurs, from deadly cyclopes to thievish boars.

As you survey the field, you must continuously evaluate tactics and strategy. Do you take out the archer in the back, or do you attack the card thief in the first row? Do you use a magic card that will hurt many foes, or do you preserve it until later?

The game offers two main quests: the “Path of the Giant” and the unlockable “Path of the Ferryman”. In addition, the “Challenge of Chronos” lets you play with a time limit. Three difficulty modes are available.

As is typical for roguelike games, death is permanent, with one exception: if you find a rare giant stone, you can retry a stage the next time you die. In addition, in each run, you can acquire both temporary and permanent buffs that will help you in future attempts.

A typical early battlefield populated by minotaurs and archers. (Credit: Louis Rigaud / Goblinz Studio. Fair use.)

The game’s story is fragmented into memories, which you will find scattered throughout the dungeon. Each memory plays a short animation which reveals an aspect of Iris’ life: her relationship with her parents, her experiences in school, and so on.

This isn’t quite enough to tell a story, and the serious topic matter (depression, anxiety, bullying) is handled in a manner that can feel a bit overwrought and superficial. For me, that was only a mild distraction; your mileage may vary.

The Verdict

I enjoyed the 15 hours or so I spent with the game tremendously. Much of this is thanks to the excellent game design. The mechanics are intuitive and communicated well through text and graphics. There’s plenty of variety throughout the two main quests, and there’s always a small thrill in encountering a new card for the first time.

Once you’ve finished the quests and unlocked everything you want to see, you’ll probably be ready to move on. While there are some extra challenges for completionists, individual runs aren’t sufficiently distinctive to make this a game you’re likely to spend 100 hours with.

If you’re looking for a roguelike that has a lot to offer without getting you addicted, Iris and the Giant is an excellent choice. 4.5 stars.

How We Know We’re Alive is a short, free narrative adventure game set in Sweden. You play as Sara, an advertising copywriter who returns to her hometown of Härunga to pay her respects to her estranged friend, Maria. We learn that Sara’s and Maria’s paths in life diverged when Sara moved to Stockholm to fulfill her aspirations to become a writer, and Maria decided to stay behind to raise a family.

Sara hates Härunga, a fictional town situated in Sweden’s non-fictional Bible Belt, but she is compelled to learn more about what happened to Maria. So she has strained conversations with the people she grew up with.

The game is rendered in gorgeous, animated pixel art and features an evocative soundtrack. It combines point-and-click mechanics with horizontal movement using the keyboard, but features no puzzles. You walk around, click on some hotspots, and talk to people (you can make choices during each conversation).

Sara really, really does not like her hometown of Härunga. The weather is doing little to change her mind. (Credit: Motvind Studios. Fair use.)

It’s a 30-60 minute story about grief, love, and alienation, and not the kind of game I would recommend playing if you’re in an emotionally dark place yourself. The dark and rainy scenery is only briefly interrupted by sun-drenched memories, and the game’s ending may put you in a somber or reflective mood.

I encountered one small bug (when I moved in another direction than the game anticipated, it kept repeating the same scene with the same dialog), and I had to play the game in window mode on Linux to avoid flickering. But these were minor issues. If and when you have the appetite for this kind of story, How We Know We’re Alive is a beautiful, moving experience.

If you want to support the work of the small indie dev team that created the game, you can send them a few bucks for the deluxe edition, which includes artwork, the game’s original script, and a soundtrack with tracks not included in the game.

Ken Liu’s short story The Paper Menagerie was the first work of fiction to pick up the Nebula, the Hugo and the World Fantasy Award at the same time—deservedly so, as it is a moving and imaginative story that harmonizes with the author’s strengths, weaving together threads of family, myth, and fantasy.

I quite enjoyed Liu’s short story collection of the same name, so I had to pick up his second collection, The Hidden Girl and Other Stories, the moment I read about it. While it held my attention, I must say that I might wait a little longer before picking up Liu’s next volume of stories.

To be fair, there are some real gems among the 19 stories assembled here. For example:

-

Ghost Days explores how memories of our culture and traditions help us hold on to a shared identity, even in a future where our species has modified its biology to adapt to other planets.

-

The Reborn takes us back to Earth, where humans are living side-by-side with aliens whose concept of self is entirely different from our own.

-

The Message is about a father connecting with a teenage daughter he has never met, in the ruins of an alien civilization.

A novella split into three stories comprises the core of the book: The Gods Will Not Be Chained, The Gods Will Not Be Slain, and The Gods Have Not Died in Vain. A young girl, Maddie, discovers that fragments of her deceased father may still be alive as a computer program. This discovery is a harbinger of a dark future in which uploaded uber-minds fight for control of the entire planet. The tale never quite finds its emotional footing, getting as lost as the world it portrays.

Liu returns to the theme of mind uploading in three stories: Seven Birthdays, Staying Behind, and Altogether Elsewhere, Vast Herds of Reindeer. I found myself waiting for some imaginative twist that justifies the inclusion of these very similar stories. Instead, I found powerful ideas rendered less potent through repetition.

This brings me to the titular story, The Hidden Girl. It’s a fantasy tale set in the Chinese Tang dynasty era, about a young girl who is abducted from home to become an assassin with mystical powers. Unfortunately, the story feels like one we’ve heard many times before, in many variants.

At 411 pages, this is a hefty collection by a prolific writer. But Liu should have taken a page from the monks in his last story, The Cutting, who reinforce their mythology by gradually erasing it. A more careful selection would have helped his gems shine more brightly. As it is, I would give The Hidden Girl 3.5 stars, rounded down for the inclusion of a promotional excerpt from Liu’s next book as its own story.

Wide Ocean Big Jacket falls into the category of game sometimes called “walking simulators” or, more generously, “narrative adventure games”. In a world rendered in simple but attractive low poly art, we are introduced to teenagers Ben and Mord, who are on a camping trip with Mord’s aunt and uncle, Cloanne and Brad.

As the player, your point of view keeps changing from one character to the next. You explore the campsite, complete small tasks like setting up the tent, and have conversations. During dialogue sequences, the game world disappears from view, and only text and a small cartoon representing the speaker are visible.

No camping trip would be complete without a campfire cooking experience. (Credit: Turnfollow. Fair use.)

It turns out that Ben and Mord are dating, and their burgeoning relationship is contrasted with Brad and Cloanne’s childless marriage. The story doesn’t build towards some dramatic conclusion or revelation—it is meant to be a “slice of life” in the moments of these characters. There’s relationship talk, birdwatching, and trashy literature.

The game succeeds at bringing Mord, Ben, Brad, and Cloanne to life in the hour or so we spend with them. It’s not a perfect experience: the writing could have used some copyediting, and the game world is so tiny as to feel limiting. The regular price of $8 is a bit high for this charming but very short journey; if you already own it thanks to The Bundle or can get it for less, I definitely recommend the trip.

The idea of cursed letters (“Send this to 10 friends or you will die”) and other artifacts of death is a common horror trope. It is also the premise of The Letter, a horror game by Philippines-based Yangyang Mobile. The game was originally crowdfunded via Kickstarter.

The Letter is set in a small fictional English city named Luxbourne. Isabella Santos, a young real estate agent, is tasked with selling the Ermengarde Mansion, a 17th century property rumored to be haunted. In the mansion, she encounters a malevolent presence that almost kills her—and she finds a cursed letter written in blood.

The game mostly plays as a fully voice-acted visual novel, but it features a few (skippable) quick time events. In each chapter, you play as a different character:

-

Isabella Santos, the young, cheerful real estate agent who discovers the letter

-

Hannah Wright, a wealthy heiress who seeks to acquire the Ermengarde Mansion

-

Luke Wright, a sleazy businessman and Hannah’s husband

-

Marianne McCollough, an interior designer hired by the Wrights

-

Rebecca Gales, a teacher; Isabella’s closest friend

-

Zachary Steele, a photographer and aspiring filmmaker; part of Isabella’s circle of friends

-

Ashton Frey, a young detective; part of Isabella’s circle of friends

You are offered choices throughout the story. Some may lead to an early death of the character you are playing, but unlock new branches of the story later. Other choices influence the relationships between the characters: Will Ashton and Rebecca become lovers, or remain friends?

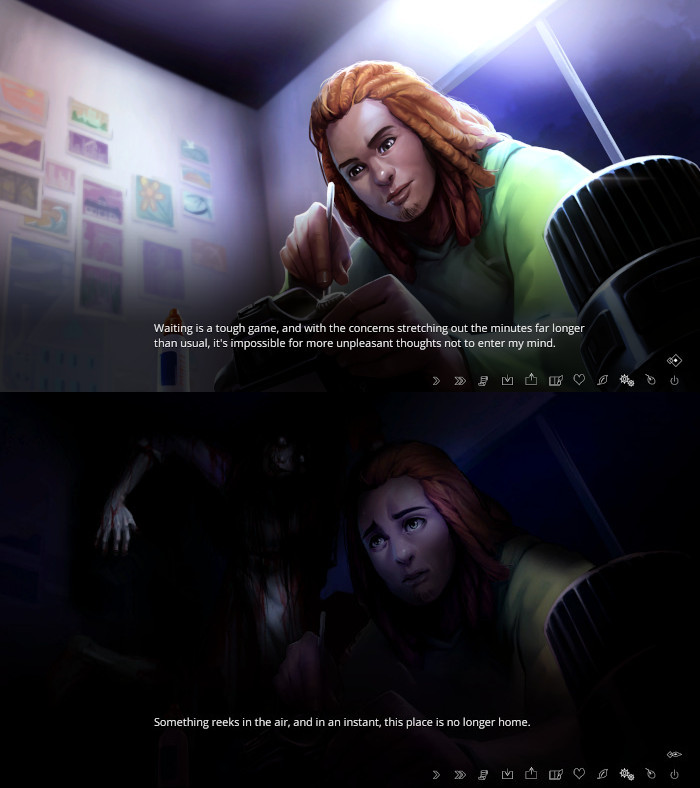

Throughout the game, everyday scenes are transformed into nightmares as Isabella and her friends are haunted by a malevolent entity. (Credit: Yangyang Mobile. Fair use.)

Show and tell, and tell, and tell

The chronology of the chapters is overlapping: you experience some of the same moments from the perspective of different characters, with their inner voice adding new layers of meaning to dialog you have already heard. A journal records significant events in the story, which is a very helpful feature if you take longer breaks between sessions.

Unfortunately, most of the characters have a tendency to blather. Where one line of inner voice text would have sufficed, we get many paragraphs of overwrought observations, recollections, and reflections. The text would have much benefited from copyediting—both to cut the fat, and to catch the occasional grammatical error or typo.

Overall, while the writing won’t win any awards, it is good enough to carry the story. Here is a short sample:

The long slog from Anslem Village by foot has already been made difficult by the light drizzle and biting winds buffeting against my body, every few seconds. By the time I’ve found cover under the trees lining the vicinity of the mansion, my shoulders are already drenched.

The paragraph sets the scene just fine, if you overlook its small imperfections (“already … already”; the slightly odd construction of the first sentence).

The text is supported by lovingly crafted visuals: animated backgrounds, animated characters, cut scenes, flashbacks. In some scenes perspective or proportions are a bit off, and the depiction of female characters like Rebecca and Hannah seems to primarily serve the male gaze (exaggerated jiggle physics included whenever they appear on the screen). Nevertheless, the art feels fresh and original, and it is the game’s strongest quality.

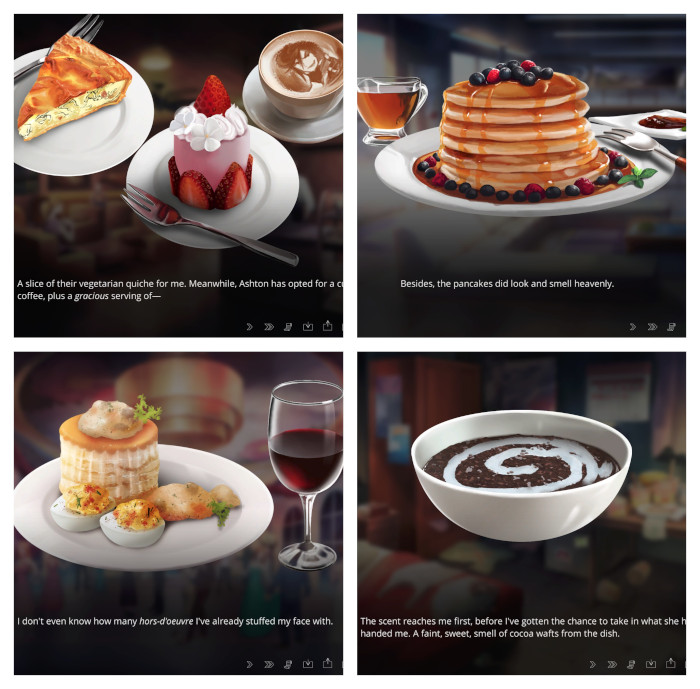

The game has an odd, amusing obsession with detailed images of food. Note the interesting latte art. (Credit: Yangyang Mobile. Fair use.)

The Verdict

The Letter may take you 15-30 hours to complete, depending on how many endings you want to see, and whether you skip through some of the text. That makes it a surprisingly long game, and this is really its biggest problem. Simply put, the game’s reach exceeds its grasp.

About two thirds of the way in, I found myself getting increasingly impatient and frustrated with the writing, but too invested in the story to stop playing altogether. The ending I got was underwhelming, and I decided to watch YouTube videos to see the alternative endings, because getting there myself would have been too tedious.

As an indie effort, The Letter is impressive in its depth, ambition, and love for detail; as a game, it falls short. My recommendation: keep an eye on Yangyang Mobile, and pick up The Letter at a discount if you find the art and premise appealing.

How would we grieve if we could order custom android replicas that will take the place of our deceased loved ones? What should the justice system of a moon colony look like? If we built a machine that always tells truth apart from lies, could we really handle the truth?

In her podcast Flash Forward, Rose Eveleth has explored questions like these since Barack Obama was still president of the United States. The premise is that by thinking about futures—dystopian or romantic, ridiculous or sublime—we become better equipped to shape the world we may one day live in.

A typical Flash Forward episode combines storytelling, interviews, and analysis to stimulate the imagination residing in the “spicy meatball between your ears”. Now, Eveleth has translated the same concept into book form.

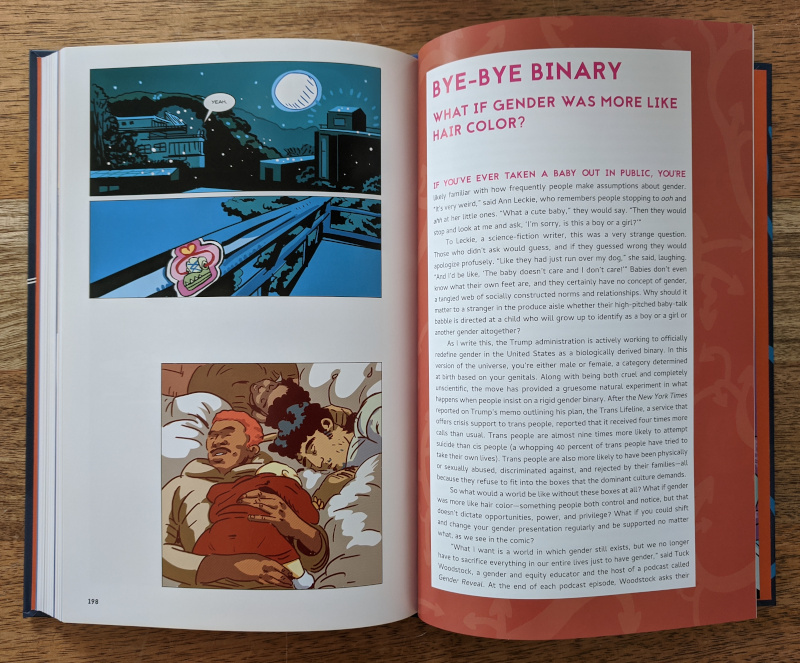

The book explores 12 different futures through full-color comics created by 14 contributors, followed by short essays written by Eveleth. The comics take up much of the 271 pages, making this a very quick read.

Each comic about a possible (or impossible) future is accompanied by a short essay that explores the topic further. (Credit: Rose Eveleth (text) / Ziyed Y. Ayoub (art). Fair use.)

It’s a book about the future, but it’s firmly grounded in the social and political discussions of the present. For example:

-

In “Welcome to Tomorrowville”, artist Ben Passmore and Eveleth wonder how the biased algorithms of a “smart” city might reinforce historical patterns of racism and marginalization.

-

In “Never Lay Me Down to Sleep”, Matt Lubchansky portrays a world in which we can fully conquer sleep with pills, and the inevitable exploitation of workers that follows.

-

In “Unreel”, Chris Jones and Zach Weinersmith tell the story of a man who controls the world through deepfakes—initially with honest motives.

As with an anthology, the art, stories, and topics chosen will surely resonate differently with each reader. Some stories felt a little too stuck in the present to give me much to mull over (the animal rights story stands out to me here); others were a bit predictable (sleep is indeed important). It’s hard to explore questions of morality without getting preachy, and the book does not always succeed at it.

But whether in book or podcast form, Flash Forward is an engaging approach to thinking about the future, and I recommend it. It also helped me discover the work of artists I would otherwise not have known about. I’d love to see another volume, featuring new artists and new futures to chew on.

Are we born with brains that are blank slates waiting only to be filled with experience? And if so, why is it so difficult to simulate that same experience in a computer? Why can a sophisticated AI be easily tricked into thinking that a cat is guacamole or that a Granny Smith apple is an iPod? How have human brains managed to adapt to the diversity of environments across the globe, from the Stone Age to the Space Age?

In How We Learn: Why Brains Learn Better Than Any Machine … for Now, French neuroscientist Stanislas Dehaene shows that the “blank slate” hypothesis does not withstand scrutiny. Our brains are equipped, from birth, with specialized neural circuits that shape a child’s intuitions about physics, arithmetic, geometry, and probability.

Dehaene cites a large body of research (including his own) that shows how young infants’ brains make sense of the world using this “core knowledge”. This research has forced a re-appraisal of older psychological models that have become popular wisdom:

Incidentally, these results overturn several tenets of a central theory of child development, that of the great Swiss psychologist Jean Piaget (1896–1980). Piaget thought that young infants were not endowed with “object permanence”—the fact that objects continue to exist when they are no longer seen—until the end of the first year of life.

He also thought that the abstract concept of number was beyond children’s grasp for the first few years of life, and that they slowly learned it by progressively abstracting away from the more concrete measures of size, length, and density.

In reality, the opposite is true. Concepts of objects and numbers are fundamental features of our thoughts; they are part of the “core knowledge” with which we come into the world, and when combined, they enable us to formulate more complex thoughts. [p. 58]

Brains vs. Machines

Like a budding scientist, an infant’s brain forms predictions about the world and then adapts its wiring based on whether the predictions match reality. This neuroplasticity is powerful, but it is highest during early sensitive periods, and dependent on innate cognitive skills—a number sense, the ability to detect faces, to acquire languages, and so on.

Dehaene contrasts this with the current generation of artificial networks, which are closer to a “blank slate” on which the characteristics of a training dataset are gradually inscribed. As a result of this naive approach, AIs lack the human brain’s multifaceted reasoning skills—”for now”, as the book’s subtitle puts it.

Hinting at what tomorrow may bring, Dehaene cites examples of artificial neural networks modeled after human cognition. For instance, a 2008 algorithm for predicting the optimal structural representation of various datasets “rediscovered” human knowledge representations like the tree of life.

One may quibble with the author’s assertion that human brains learn “better” than machines, given that the latter have already excelled in specific domains. Just ask Go player Lee Sedol, who retired from professional play and called AI “an entity that cannot be defeated”.

A Theory of Learning

But the focus of the book are humans, not machines. The author’s goal is nothing less than a theory of learning that teachers, parents, and students can apply in practice. He suggests a model based on “four pillars of learning”: attention, active engagement, error feedback, and consolidation.

From these four pillars he develops concrete recommendations for educators. Many of them may match the instincts of progressive teachers: anxiety and stress prevent learning; students need to be engaged as individuals; sleep is essential. However, Dehaene is highly critical of unassisted discovery learning and the popular idea of learning styles.

Dehaene does not take a one-sided view in the “nature versus nurture” debate; instead, he explains the complex interplay between our biology and the world we inhabit. Biological evolution has placed constraints on us, but it has also allowed us to reason about the workings of our own brains, and to journey to other planets.

The Verdict

As a whole, I highly recommend Dehaene’s book. As befits the subject, he is a great (occasionally witty) teacher who uses straightforward explanations and illustrations in order to systematically advance the reader’s understanding of a complex subject.

While I found the author’s level of certitude—when he talks about animal intelligence or learning styles, for example—a bit off-putting at times, that too can be the mark of a teacher in love with their subject. It is a passion he successfully passes on to the reader.

If On A Winter’s Night, Four Travelers is a gift—literally. The indie game by Laura Hunt and Thomas Möhring is completely free, but you could easily mistake it for a commercial title. Its pixel art compares favorably both to classic point and click adventure games by LucasArts, and to modern ones like Kathy Rain. Möhring’s other credits include stunning concept art for the Netflix show The Queen’s Gambit, and each scene in the game feels like a small work of art in its own right.

The four titular travelers meet at a masquerade ball that takes place on a train in the late 1920s. Most of the story is told through flashbacks in which you experience a defining episode in the life of one of them. Behind their masks are troubled souls—as the player, can we only experience their stories, or change them? Like Italo Calvino’s book that inspired the game’s title, the game suggests that we interrogate it, not merely consume it.

This is not a lighthearted romp—think I Have No Mouth, But I Must Scream, not Monkey Island. You’ll be confronted with themes like mental illness and homophobia, and with graphic depictions of violence. Hunt and Möhring invite us to put on a mask and imagine the lives of these characters, whose worlds come alive in the game’s art and music. For the soundtrack, the developers have drawn on freely available recordings of classical music and songs from the depicted era.

Lighting effects and subtle animations make even small scenes, like this brief encounter in a hallway, highly memorable. (Credit: Laura Hunt and Thomas Möhring. Fair use.)

There are small puzzles you have to solve to advance in the story, but none are likely to stump you for very long. That’s in part because there’s no inventory—you occasionally have to pick up an item, but you then immediately use it elsewhere in the scene. It’s point and click reduced to its essence.

With these simple mechanics, the game achieves surprising depth. For example, in the first story, you choose whether to interpret a telegram you have received from a lover positively or negatively. Depending on your choice, many subsequent interactions and observations will be different. In another story, you have to pay attention to sounds and voices instead of hunting for pixels.

Hunt and Möhring have made it clear that they do not want to be paid for the game, but they have suggested that an artbook and soundtrack may become available for purchase at a later date. If On A Winter’s Night, Four Travelers, then, is like a book you can pick up at any time from the library called the Internet. If you’re in the mood for a story that shows a little more darkness than light, I strongly encourage you to check it out.