Reviews by Eloquence

Art books about video games tend to be authored by collectors and enthusiasts, often lacking a critical outside perspective. Never Alone: Video Games as Interactive Design accompanies an exhibition at the New York Museum of Modern Art of the same name.

In the book, the organizers of the exhibition explain why they selected the specific titles they did. Richly illustrated with screenshots and printed on glossy black coated paper, each featured work is given space to look its best in a static format.

The book is divided into three sections, The Input, The Designer, and The Player, which loosely serves as a way to offer a different focus when discussing each title.

For example, the book explains how sandbox games like Minecraft and SimCity come to life through player actions and emergent behaviors in ways their designers could never have predicted.

The books makes good use of space to immerse the reader in each title’s visuals. Depicted here is “Monument Valley”, a gorgeous mobile game. (Credit: Ustwo Games (Monument Valley) / MoMa. Fair use.)

Occasionally, the book offers a perspective on how games can perpetuate real world biases, as in the ridiculous cast of characters that comprise Street Fighter II, based on national and ethnic stereotypes (the “Yoga Master” Dhalsim was literally named after an Indian restaurant; his name translates to “lentils and beans”).

Among the 35 games are classics from video game history (Space Invaders, Tetris) and lesser known titles that have explored new possibilities of the medium (the Memento Mori mini-game Passage, the minimalist rhythm game Vib-Ribbon).

It’s a fine selection, and the only fault I can find with the book is that it’s a bit short (just under 140 pages) and a bit expensive (the official sales price is just under $40 as of this writing). With those caveats in mind, I would recommend it to anyone who appreciates the art and design of games.

Full list of titles featured in the book

-

Pong (and its Magnavox Odyssey precursor)

-

Space Invaders

-

Asteroids

-

Pac-Man

-

NetHack

-

Tetris

-

Snake

-

Katamari Damacy

-

Canabalt

-

Monument Valley

-

Tempest

-

Yars’ Revenge

-

Another World

-

Myst

-

Portal

-

Dwarf Fortress

-

Passage

-

fl0w

-

Flower

-

Journey

-

Papers, Please

-

Never Alone

-

This War of Mine

-

Inside

-

Everything is Going to Be OK

-

Getting Over It with Bennett Foddy

-

Return of the Obra Dinn

-

Street Fighter II

-

SimCity 2000

-

The Sims

-

Vib-Ribbon

-

Eve Online

-

Minecraft

-

Biophilia

-

The Stanley Parable

In British author Ian McEwan’s 2016 novel Nutshell, the protagonist is a precocious fetus, who shares his observations about the drama unfolding outside the womb and ruminates about the human condition. The conceit sometimes serves a stand-in for the author to hold forth about subjects dear to his heart.

McEwan’s latest work, Lessons, takes the more honest approach of blending fiction and autobiography. The main character, Roland Baines, is the author’s alter ego, with a point of departure in his teenage years that leads to a quite different life.

The road not traveled

McEwan was born in 1948; his father rose to the rank of Major in the British military after World War II, and young Ian spent parts of childhood in Libya, Singapore and Germany. He has described his father as a “hard-drinking man, quite terrifying”.

In Lessons, he processes these experiences by describing childhood episodes in Roland’s life, focusing on moments in Tripoli that give Roland a hunger for the elusive and the extraordinary.

After Roland is shipped to boarding school back in England, an encounter with a piano teacher (not based on any actual person) pushes him down a road the author never traveled.

As a young man, Roland becomes a drifter, avoiding career and family until the 1980s. Then he falls in love with Alissa, whose life is similarly unmoored, and who harbors dreams of becoming a novelist. Soon enough, Alissa gives birth to their son, Lawrence. A child might anchor them both—but Alissa decides that she has other plans.

Unfolding history

In McEwan’s narrative, we jump back and forth in time—to the 1950s, the 1980s, the 1940s—only to eventually find ourselves in the present day, when Baines tries to make sense of his untidy life story. Historical events like the White Rose resistance against the Nazis, the Chernobyl disaster and the fall of the Berlin Wall provide a momentous backdrop to the much smaller scale events at the heart of the story.

This is a story that rejects the notion that narratives must offer closure. It encourages the reader to reflect on the past and future points of departure in their own lives. It is also metafiction, in which Alissa’s decision to “raid her past” in order to craft her own novels is contrasted with McEwan’s choice to do the same.

I often find myself frustrated when authors jump between timelines, or nest flashbacks within flashbacks. McEwan manages to bridge the decades without leaving the reader bewildered or lost. That’s in large part thanks to his mastery in setting a scene and bringing characters to life. Opening a random page, here is a description of Alissa’s father:

Heinrich’s manner and convictions were remote from Roland’s but he warmed to the older man, who wore a tie at all times and sat stiffly upright in even the softest chairs. He was an active member of the Christian Democratic Union, a lay reader in the local church and had given his life to the law as it impacted on the lives of farmers in the surrounding countryside. He approved strongly of Ronald Reagan and believed that Germany needed a figure like Mrs. Thatcher. And yet he thought rock and roll was good for what he grandly called the “general project of happiness".” He didn’t mind men with long hair or hippies so long as they caused no harm to others, and he thought that homosexual men and women should be left in peace to live their lives as they wished.

In a recent interview, McEwan described his approach to writing the book. For key events in Roland’s life, McEwan intentionally avoided thinking about what Roland would do, until the time finally came to write it. When Roland rings the doorbell to his piano teacher’s home later in life, the author rings it with him. Perhaps it’s this approach that makes Lessons feel lifelike, both engrossing and anticlimactic.

The Verdict

Roland Baines appears to share McEwan’s liberal politics, leading Jacobin to call Lessons “a centrist agitprop novel”. In truth, Roland’s views of the world are too disjointed and incoherent to turn him into an effective advocate for any particular political position.

With Lessons, the aging author has written a kind of secular, intergenerational homily, which readers may find bland, edifying, or—in my case—both. The lessons the book conveys most successfully are between the lines, in the highs and lows of Roland’s life.

I found the book more engaging than Nutshell and Machines Like Me, but it lacks the dramatic payoff of McEwan’s finest work (Atonement). If you have enjoyed any of the author’s other works, I would definitely recommend it.

The protagonist holds a stressful job in the big city. Circumstances lead them to an extended stay in their old hometown. They rekindle old relationships, form new ones, and ultimately have to make a big decision.

It’s a trope all too familiar from film and television, but less common in video games. Lake, released by Dutch indie studio Gamious in 2021, embraces the premise wholeheartedly.

Holiday job

The year is 1986. You play as Meredith, a 44-year-old programmer who spends her holiday in her old hometown of Providence Oaks, Oregon. It’s not much of a vacation, though! For two weeks, you fill in for your dad at the local post office, delivering letters and packages to members of the small lakeside community. Meanwhile, your parents are on an actual vacation in Florida.

The core mechanic of the game is to drive the Post Office truck, put letters in mailboxes, and deliver packages to homes and businesses. Occasionally, this offers opportunities for interaction with the town’s residents. These interactions are used to advance a slice-of-life narrative.

There’s no larger plot to uncover here, but you can get involved in small town drama. A lumberjack is protesting plans for real estate development; a young couple is on the run from the law; a small video rental store is fighting for its survival. Many of the characters are one-note stereotypes, but it’s still fun to talk to them.

Trucking along

These interaction opportunities are only delivered in small morsels. You spend a lot of your time just driving around and delivering mail without talking to anyone. (Occasionally, Meredith will issue a bit of monologue when putting a letter into a mailbox, like “Here’s your mail”.)

The local radio station helps break the monotony, until you notice that the same handful of songs keep repeating, at which point you’ll want to turn the radio off to keep your sanity.

Meredith is driving her truck around the lake. Get used to the view, because you’ll be seeing it a lot. (Credit: Gamious. Fair use.)

When outside the truck, Meredith can walk slowly or … walk slowly. In theory, you can accelerate her walking speed, but the increase is almost imperceptible.

Lake, then, is a game best played when you want to let your mind wander. The town is pretty to look at, and there are some nice details, like a fox or a deer crossing the road, or changes in the weather.

Uncanny hometown

Overall, however, the game’s reach exceeds its grasp. There’s a reason most “walking simulators” stick to just that: walking. The driving mechanic is awkward and immersion-breaking—you can drive your truck into anything or anyone without as much as a honk or a frown.

On my system, which plays far more demanding games without issues, the game’s frame rate dropped from time to time, and the audio sometimes fell out of sync. There were also occasional visual glitches: cars floating in the air, people disappearing, lights flashing or flickering. Close-ups on characters are straight from the uncanny valley, with dead stares and robotic lip movement.

The game has three different endings; to its credit, you can pursue a male or female love interest. It doesn’t really broach the issue of small town homophobia in a meaningful way, and I was disappointed in the limited choices it ultimately offered for Meredith’s future.

The Verdict

All in all, I cannot recommend Lake: the mail delivery mechanic is too tedious, the technical problems are too numerous, and the story is too underdeveloped. Indie games like Firewatch and have demonstrated that it’s possible to deliver technically excellent narrative experiences with a small team—Lake never reaches that high bar. That said, many folks have found enjoyment in the game, and if you’re really looking for that small town vibe, you may want to check it out.

Philip Ball is a veteran science writer whose books have shed light on a wide range of subjects, including molecular physics, pattern formation, music psychology, and quantum physics. In The Book of Minds, Ball attempts to penetrate the mystery of “mindedness”.

How would it feel to experience the world like a bat or a bee? Can we create artificial minds? And if alien life forms are out there, how would their minds relate to ours?

Imagination and its limits

Ball introduces the idea of a “space of possible minds” in which to situate any being. Using dimensions such as consciousness, agency, intelligence, and experience, it becomes possible to at least speculate systematically about how an animal mind might differ from our own.

Ball then surveys the forms of thinking, sensing and reacting that can be found in living things. He provides a brief introduction to newer theories of consciousness like Integrated Information Theory, and summarizes the state of artificial intelligence around the time the book was written.

The author frequently reminds us that, while we can speculate about dimensions of “mindspace”, we cannot transcend the limitations of our own minds when imagining the experience of other beings.

That doesn’t stop him from speculating about the possible minds of extraterrestrials. Ball notes that much of our science fiction merely extends human qualities and motivations into “alien” minds—the war-like species, the scientific species, etc. He reaches the obvious conclusion that we can say very little about what alien minds would actually be like.

Why agency matters

In the penultimate chapter, Ball engages in an impassioned defense of the concept of “free will”. While acknowledging that the term is problematic due to metaphysical connotations and lack of clear definition, he argues that the concept of agency as realized through minds is crucial to make sense of the world.

Ball dismisses questions of determinism as irrelevant. Of course, he says, everything happens because it could not be otherwise—that’s a banal, even tautological observation. But the causes of events don’t become more intelligible by reducing a person’s decisions to the interaction between molecules in their brains.

Minds produce decisions—that’s what they evolved to do—and thereby they cause things to happen. That distinguishes minds from other objects in the universe. We therefore need to approach agency as a subject of study: Why and how do minds decide certain things? It’s an implicit defense of fields like psychology for comprehending a universe that has minds in it.

While the chapter is essentially a long philosophical argument, I found it to be the most interesting one in the book. As for the remainder of The Book of Minds, regular readers of science writing are unlikely to encounter a lot of ideas they’ve never heard of before.

The Verdict

Ultimately, Ball’s core subject is riddled with so much uncertainty that it does not really warrant a 500-page book. Readers have to work through a lot of variations of “we don’t know” or “we can’t know” to get to the ideas Ball wants to bring across. That’s a shame, because those ideas are interesting—they’re just buried in prose.

Florence is the short interactive story of how 25-year-old Florence Yeoh finds love—and of what happens after that.

You scroll and click (or tap) your way through the story by way of microgames: brush your teeth, pick up some items, open a box. The game wants you to advance through the story and does not put any stumbling blocks in your way.

There’s almost no writing. Instead, the story is largely told through pictures, animations, music, and (in some poignant ways which shouldn’t be spoiled!) its interactive elements.

Sometimes the people you care about may need a little push. (Credit: Mountains Games / Annapurna Interactive. Fair use.)

The soundtrack relies heavily on piano, cello and violin. It adapts to the mood of each chapter and harmonizes beautifully with the artwork. Together, the art and music give the game emotional depth despite its light and simple story.

It’s a very well-crafted experience that lasts about 30-45 minutes. Yet, it also trades in well-worn clichés and eschews any kind of social commentary. This isn’t a game to make you think—it’s a game to make you feel. (That’s not to say that there isn’t a takeaway, but it’s primarily an emotional one which I won’t spoil for you.) If that’s what you’re looking for, I can wholeheartedly recommend it.

You don’t know what to expect from the odd-looking wooden box which now holds pride of place in your living room. You turn it on and fumble with the controls for a while. Suddenly, the voice of an opera singer pierces the static.

It’s like magic, coming to you through the air, filling the world with possibility and wonder.

What is it like to witness the birth of an invention set to transform humanity? I was not around when radio was invented, but I did experience BBS culture and the early web of the 1990s. It was a time when millions of people were “coming online” for the very first time, without any idea of what that meant. The Internet, as David Bowie put it in 1999, was “an alien lifeform”.

The past that wasn’t

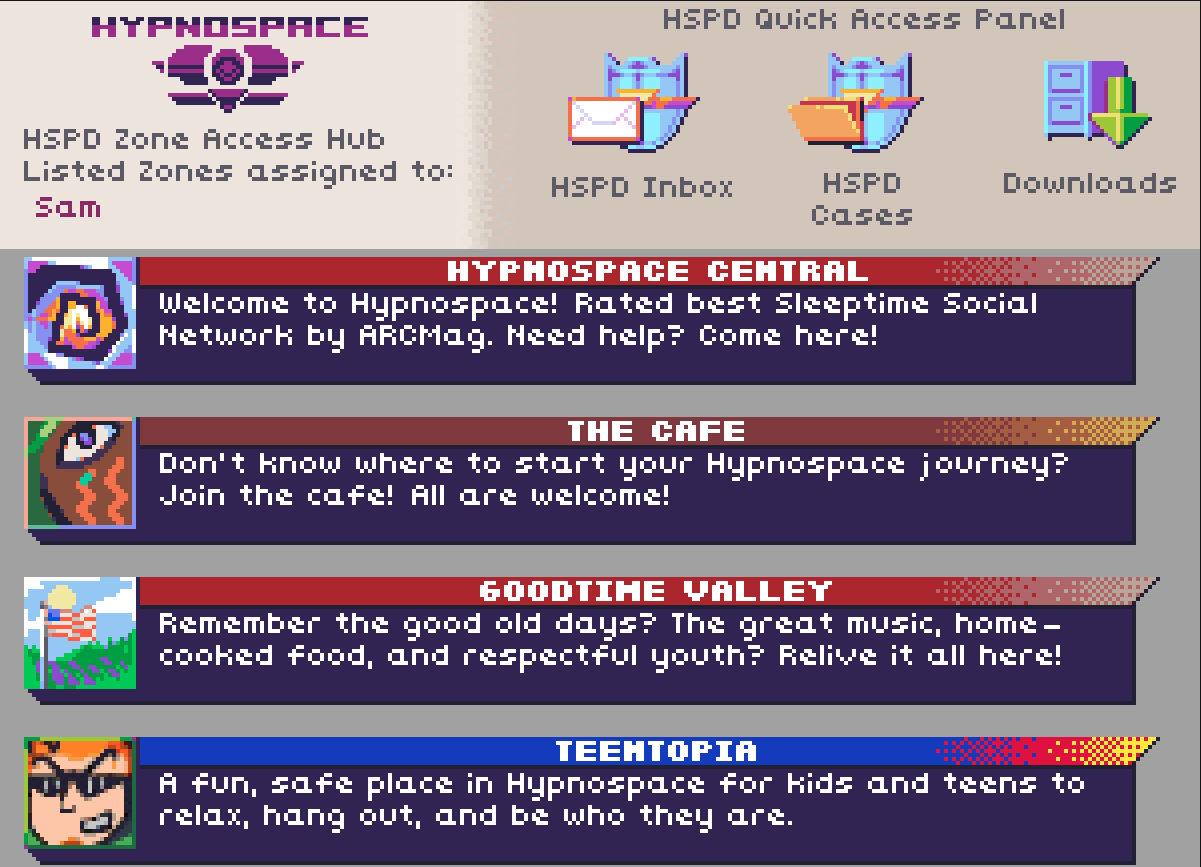

Hypnospace Outlaw is a 2019 indie game that lets you experience the birth of a surreal alternative reality version of the early web. The year is 1999. You are a community enforcer in hypnospace, a web-like network accessed through special headsets people wear during their sleeptime.

You play the game through a desktop environment that looks a bit like Windows 98, macOS and Microsoft Bob were put through a blender. It comes with a browser, an email-like messaging app, a virtual wallet, and a download manager.

You interact with the world of Hypnospace Outlaw through a desktop environment that combines the best and worst of computing around the turn of the millennium. Fortunately, downloads are a lot faster in this simulated reality. (Credit: Tendershoot. Fair use.)

Unlike the web, hypnospace is controlled by a single corporation, Merchantsoft. Its customers can create pages, which are organized into different communities like “The Cafe” and “Goodtime Valley”. On the surface, it resembles web communities like Geocities or its modern-day nonprofit successor, Neocities.

Yet, as the player, you are keenly aware that this is not the early web but an alternative history. You don’t know the rules of this world, but you are tasked with enforcing them. Soon, you receive your first assignment: to trawl hypnospace for copyright violations. Maybe this alternative reality isn’t so different after all…

Much of the gameplay is exploratory: browsing pages, downloading and trying little apps, getting rid of viruses that came with the apps you just tried, and so on. The assignments you receive guide you through the game’s larger narrative and timeline.

Rhythm of discovery

Music is everywhere in Hypnospace Outlaw. The game world is suffused with fictional bands and their creations, from the optimistic MIDI sound of the Millenium Anthem to hyper-commercial, autotuned “coolpunk”; from “Seepage” tracks that sound like Linkin Park demo tapes to the wonderful ridiculousness that is “The Chowder Man”.

The communities you interact with in the game are haplessly curated by the Merchantsoft corporation, though you’ll soon discover corners of hypnospace that have eluded its control. (Credit: Tendershoot. Fair use.)

It really does feel like you’re back in the late 1990s, building a library of MP3 files from dubious sources and trying to figure out what’s actually worth listening to when you can listen to anything.

Amidst the surrealism of it all, the game does have things to say: about commercial control over online communities, about critical thinking, and about the pure joy of free expression in a nascent medium. As I reached the end of the story, I found myself far more emotionally invested than I expected.

The Verdict

I recommend Hypnospace Outlaw without reservations; it truly is a small masterpiece of immersive storytelling. But I would suggest keeping it in your backlog until you have a few hours at your disposal and are ready to fully engage with its world.

This is not a game to rush through, but an experience to savor. As Fre3zer would put it: you gotta “chill it right”.

Imagine you find an alien spacecraft crashed in your backyard. A door has cracked open. You carefully step inside. You discover a world beyond your comprehension. Objects appear before your eyes, only to disappear into thin air. Lights flash in colors you cannot see. It will take humanity’s brightest minds years—decades—to make sense of it all.

Biology is a science attempting to comprehend something no less strange or bizarre: the evolved nano-machinery that constitutes what we call life. We give our discoveries opaque names. Ribosomes. The Golgi apparatus. Neutrophils. When those get too long, we abbreviate. MHC class I and II. ACE2. CD24.

Here lies a wondrous and endlessly fascinating world. Understanding it better could enrich our lives and help immunize us against dangerous pseudoscience. If only we were better at describing this complex, seemingly impenetrable universe inside our own bodies!

Philipp Dettmer is no stranger to making the complex comprehensible. He founded a YouTube channel called Kurzgesagt (“in a nutshell”), which publishes lovingly crafted videos on subjects like wormholes, geoengineering, and brain-eating amoebas. Thanks to brilliant animation, epic music and a dark sense of humor, every video is a treat.

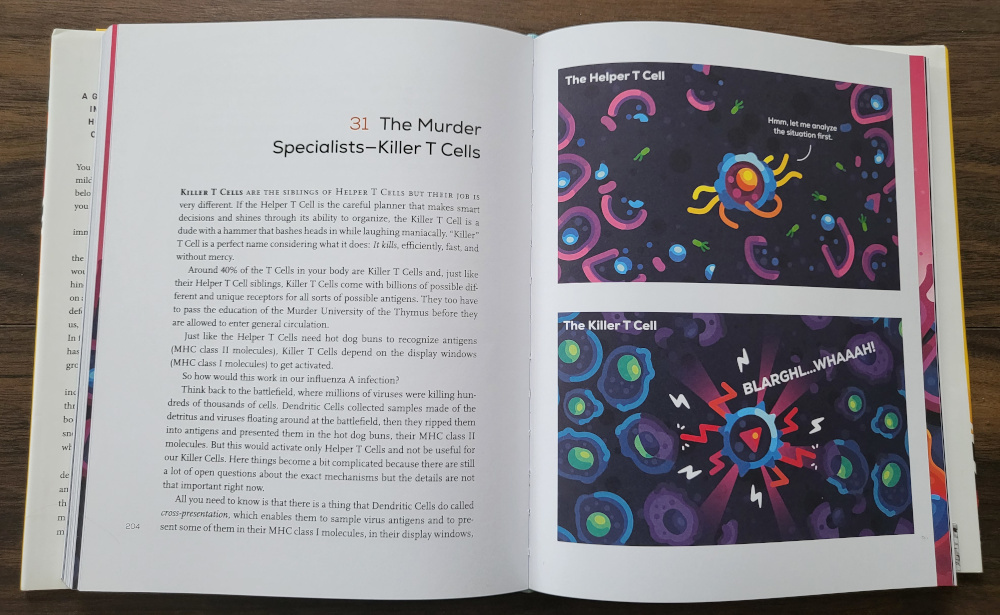

Immune: A Journey into the Mysterious System That Keeps You Alive is Dettmer’s first attempt to bring Kurzgesagt’s trademark educational approach into book form. On 341 pages, Immune sheds light on the incredibly complex macromolecular machinery that protects us against bacteria, viruses, and even snake venom and parasitic worms.

Most illustrations are more understated than the ones shown here, but this is not a book that shies away from depicting a Kiler T Cell saying “BLARGHL”. (Credit: Philipp Dettmer / Random House. Fair use.)

This is not a textbook. Nor is it the kind of pop science writing that tries to make science accessible by giving you lots of biographical detail about scientists. It’s strictly focused on the actual mechanics of the immune system, but written in a style that’s entirely Dettmer’s own. To give a small sample:

The Neutrophil is a bit of a simpler fellow. It exists to fight and to die for the collective. It is the crazy suicidal Spartan warrior of the immune system. Or if you want to stay in the animal kingdom, a chimp on coke with a bad temper and a machine gun. [p. 59]

Of course, Dettmer frequently reminds us that the immune system is not, in fact, sentient or intentional. It’s just that these kinds of analogies are too darn useful to refrain from using them. So, Dettmer talks about hot dog buns, display windows, and desert kingdoms as he helps us navigate the complex nano-scale landscape inside our bodies.

But analogies only go so far, and the book uses biological terms and plenty of straightforward illustrations. At the same time, Dettmer will often (a bit too often) emphasize that he’s still simplifying things greatly. The book is littered with entertaining footnotes that expand on the text.

Cells with two-factor authentication

The immune systems of humans and other animals don’t just have to kill invaders. They have to adapt to viruses they’ve never encountered before, detect cells that have been hijacked, calm down when a threat has been eliminated. To make matters worse, the attackers evolve rapidly!

Immune responses involve the innate immune system, a sort of standing army, and the adaptive immune system, which crafts specialized responses for novel threats. Together, they self-organize into a complex dance. Isolate the threat. Sample data. Ramp up immune responses. Kill or neutralize invaders. Detect cells that behave suspiciously. Mess with virus production.

Perhaps most fascinating is our bodies’ ability to learn and remember—to acquire immunity. At its heart is what Dettmer calls the largest library in the universe: T-cells. Wikipedia has a more understated but no less awe-inspiring description:

Each mature T cell will ultimately contain a unique T-cell receptor that reacts to a random pattern, allowing the immune system to recognize many different types of pathogens. This process is essential in developing immunity to threats that the immune system has not encountered before, since due to random variation there will always be at least one TCR to match any new pathogen.

It takes time for our adaptive immune system to find the perfect match for any given threat. But once it has done so, it switches into a kind of mass-production mode, to produce vast numbers of antibodies tailored to a specific enemy.

To avoid misfiring, cells perform complex verification dances. T-cells undergo a selection process that weeds out ones that might attack the body. And they must be matched with another cell type (B-cells) that have been activated by the same threat. Dettmer calls it a kind of two-factor authentication.

As someone working a lot with technology, I found these comparisons illuminating. Understanding the sophisticated evolved security responses of our bodies may very well inspire us to develop better ways to deal with novel threats of a more digital variety.

Knowledge as immunity

Our brain, in a way, is part of our immune response. Our decisions on what to eat and drink, what to do with our free time, how to prevent and how to treat illness—they profoundly influence our ability to stay healthy, and to get better. When we believe things that are patently false, it can literally kill us.

Dettmer spends the final sections of his book trying to convey how understanding our immune system can help us make better decisions.

He explains the remarkable accomplishment of vaccination as a way to train the body without hurting it: like a dojo where you learn to fight with weapons made of foam and paper. In contrast, parents who opt their kids out of vaccines are sending them to a “Nature Dojo”:

The philosophy of the head trainer is that kids should train with real weapons, real knives and swords, so they are better prepared for the real dangers of the world. After all, it is more natural and real life just is dangerous. From time to time, a student will get a deep cut and require stitches. And yeah, OK, there may be a lost eye and sometimes a kid may die. But it is the natural way! [p. 240]

He asks us to question dubious claims about “boosting your immunity”—reminding us of the immune system’s mind-boggling complexity and interplay of countless parts, where any actually effective intervention can have disastrous effects. He tells us to exercise (it’s obligatory in any book of this kind), and describes how stress can knock our immune system out of balance.

These final sections of the book sometimes get a bit rambling. The most muddled chapter discusses the popular misconception that hygiene has weakened our immunity against disease. Dettmer argues for preserving good hygiene while also embracing the role of nature and dirt in our lives—a reasonable argument that’s unfortunately not very coherently made.

The Verdict

With Immune, Dettmer has managed something very difficult: to write a long book almost entirely about the mind-boggling macromolecular and cellular machinery inside our bodies, without fluff, that’s entertaining to read. I would love to read similar books about subjects like epigenetics, metabolic pathways, or neurobiology!

Science books often have an incongruous approach to visual explanation. Immune is the rare exception—while it does not have as many illustrations as some readers might expect from the Kurzgesagt founder, what’s here supports the text perfectly in a consistent, pleasing style.

The latter parts of the book would have benefited from a bit more rigorous editing, but I’m glad that Dettmer’s funny and casual voice hasn’t been whittled down to science-journalism-speak.

All in all, I cannot recommend the book highly enough, and would give it a full 5 stars.

I love a good romantic tale, even of the overwrought variety (I am a The Notebook enjoyer). Therefore I was happy to give Big Dipper a try, which is a short, kinetic (choice-free) visual novel about a romantic encounter on New Year’s Eve. In case you’re wondering, it’s all very chaste stuff; the title is no naughty double entendre.

Developed by Team Zimno from Russia [*], the story is told from the perspective of Andrew, a somewhat sullen young man who encounters his manic pixie dream girl when a woman named Julia literally sleepwalks into his life and his cabin.

The game throws in a bit of the supernatural, but it’s over after less than two hours, so it doesn’t really go very far with any of it. That’s a shame, because earnestly incorporating Slavic folk tales could have made things a lot more interesting!

The relationship between Andrew and Julia develops implausibly. They grow closer through sharing stories of loss of alienation with each other, but the romance is otherwise just rushed along a “they dislike each other → they love each other beyond measure” path without ever building genuine momentum.

We’re only in the first scene, and there are already typos like “busrt” instead of “burst”. (Credit: Team Zimno. Fair use.)

Big Dipper certainly gets the aesthetics right. Made with Unity, the game looks better than your average visual novel, with nice animations for the snowfall outside and the cozy fireplace inside. The character art and full-screen graphics also look good, and are enriched with chibi-style pictures during key scenes.

Unfortunately, it’s hard to overlook the shortcomings. Aside from a rushed story that doesn’t withstand the slightest scrutiny, it’s difficult to justify the lack of attention to detail in the writing. You’ll notice the first typos and misspellings just a few paragraphs in, and we’re talking about glaring ones (“busrt” instead of “burst”, “cheked” instead of “checked”) that could have been caught with any spell checking tool.

Big Dipper is only $5, but you’ll find much better romantic visual novels even for free. Unless you’re desperately looking for a winter-themed pick-me-up and are willing to look past its issues, you can safely skip it.

[*] It’s worth noting that the authors have publicly spoken out against Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and against Vladimir Putin.

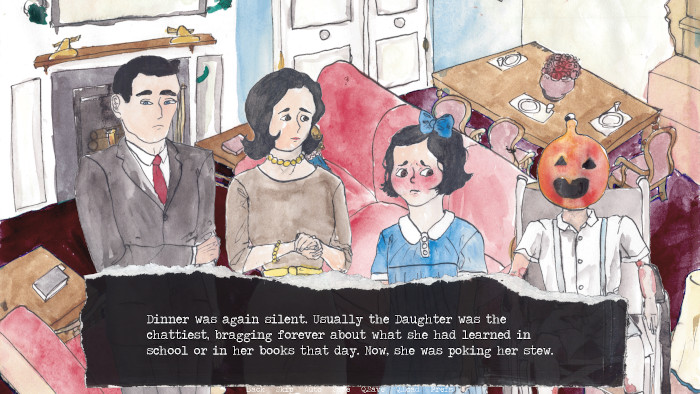

Pumpkin Eater is a kinetic visual novel, which means that it’s a story with art and sound, but with no player choices. The $2 regular sales price suggests a short story, and indeed I finished it in about 30 minutes.

Given how short it is, I don’t want to give too much away. In a nutshell, it’s about a family who loses a child in an accident but cannot let go. What follows is a tale of decay and insanity, told in (the authors assert) a medically accurate manner.

The characters and backgrounds are lovingly painted in watercolor, which creates a contrast with the story’s morbid content. (Credit: thugzilladev. Fair use.)

I appreciate attempts to demystify death, even if it’s done in the form of a horror story. Ultimately, that seems to the point of the game, which comes complete with a glossary.

The story is engaging, and it uses music and sound effects well. It won’t scare your pants off, but it might make you lose your appetite. It is also likely to stay with you. 3.5 stars, rounded up.

When governments, corporations and other organizations act unethically or illegally, only people on the inside may know about it. If they choose to tell someone who might bring about change, they become whistleblowers.

Published in 2001, C. Fred Alford’s Whistleblowers: Broken Lives and Organizational Power examines the personal sacrifice it takes to oppose an organization’s actions. From interviews and a review of prior research, Alford concludes that in spite of many legislative attempts to protect whistleblowers, retaliation is the norm, not the exception.

How organizations fight back

Whistleblowers are often not fired immediately. They are moved to “offices” that previously served as closets; their responsibilities are curtailed; their performance is put under a microscope. Only after sufficient time has passed to create distance to the act of whistleblowing, they are fired, frequently for “poor performance”.

After losing their job, they may find it impossible to work in their chosen sector again, thanks to informal blacklists. Whistleblowers are portrayed as “nuts and sluts”, their sanity and character called into question. As Alford puts it, the process is complete “when a fifty-five-year-old engineer delivers pizza to pay the rent on a two-room walkup.”

Considering this characterization, one might expect Alford to support whistleblower anonymity. Not so—anonymity, he claims, is a road to nowhere (p. 36):

Anonymous whistleblowing happens when ethical discourse becomes impossible, when acting ethically is tantamount to becoming a scapegoat. It is an instrumental solution to a discursive problem, the problem of not being able to talk about what we are doing. Whistleblowing without whistleblowers is not a future we should aspire to, any more than individuality without individuals or citizenship without citizens. If everyone has to hide in order to say anything of ethical consequence (as opposed to “mere” political opinion), then we will all end our days as drivers on a vast freeway: darkened windshields, darkened license plate holders, dark glasses, speeding aggressively to God knows where.

Personally, I think an “instrumental solution to a discursive problem” is still a fine solution, especially if it happens to save lives or serve the public interest. Much as Alford agonizes about the sacrifices whistleblowers make, he seems unwilling to imagine a world in which those sacrifices can be lessened.

Psychoanalysis to the rescue

Because many of the people Alford spoke with attended self-help groups (which selects for trauma), and because his book rarely deals in numbers, it’s difficult to say how statistically valid his observations are. Much of the book is focused on psychoanalysis: What causes whistleblowers to act, and how do they process the consequences of their actions?

Alford theorizes that whistleblowers are motivated by what he describes as “narcissism moralized”. To put it another way, whistleblowers can tolerate the alienation from everyone else more than they can tolerate being in conflict with their idealized moral self.

It’s a reasonable argument, considering that whistleblowers often act alone—so their impulse to act is often likely the result of an inner conflict. But when he characterizes whistleblowers’ motives and feelings, Alford readily dismisses evidence that isn’t consistent with his own views.

In describing one case, he writes: “Ted protests too much. For that reason I distrust his account” (p. 39). This kind of reasoning makes me worried that the author may be an unreliable narrator of whistleblower motivations, and I would rather read more quotes and fewer abstract characterizations.

How many whistleblowers discuss their actions with loved ones beforehand? How many are deeply appalled by imagining the consequences of the organization’s actions on the outside world? What Alford offers us are generalizations, made more tedious with frequent repetition and verbosity, for example, when he writes about the state of “thoughtlessness” (p. 121):

Thoughtlessness stems not merely, or even primarily, from fear. Thoughtlessness arises when we are unable to explain our fears—that is, make them meaningful, comprehensible, knowable. This happens when we lack the categories to bring our fears into being. Common narrative is, I’ve argued, of little help in this regard.

Social theory could be more helpful than it is. Liberal democratic theory assumes that politics is where the action is, and so it assumes that individualism is possible. Foucault’s account assumes that individuals don’t exist. Neither approach gets close enough to life in the organization, to say nothing of the lives of those who suffer the organization, to help individuals make sense of the forces arrayed against them.

If you enjoy the kind of analysis that says in 100 words what could be said in 10, you’ll find plenty of it here.

The Verdict

In fairness, Whistleblowers is a short book (170 pages including the index), and it does tell some interesting stories about different types of whistleblowers in different fields, from engineering to accounting.

It offers some metaphors which I’ll almost certainly find myself using again—for example, it describes life after whistleblowing as akin to space-walking, because many whistleblowers have learned the hard way that the world doesn’t work the way they thought it did.

The most useful takeaway from Alford’s book is a deeper understanding of the often very heavy cost of whistleblowing. Alford ultimately characterizes it as a “sacred” act; I would compare it perhaps with blasphemy. To understand the cost of telling the truth should prepare us to lessen it.