Latest reviews

Opensource ad blocker for Android that filters all outbound requests for ads and tracking using any combination of premade lists, whitelist and blacklist. You can also switch dns providers by selecting from a list or adding one. UI is simple and effective.

Blokada works by using Android’s vpn feature to route all outbound requests through it. This allows it to filter all requests that come from the device.

Long Term Update

After 6 months of usage, the only issue that came up is occasional issues with program staying alive. The app silently died so I didn’t notice for a while. Turning on the Keep alive option under advanced settings seems to fix the issue. This puts up an always on notification to keep Blokada alive. This means you’ll have 2 notifications up almost all the time for this app.

Verdict

This is a must have app for Android

Posteo is great if you are looking for a solid, privacy-focussed email provider. They are not free, but at 1 EUR / month well worth the money. They offer email, address book, calendar and notes functionality using their web interface or standard protocols (IMAP, CardDAV, CalDAV). In addition to the normal transport security (including DANE server-to-server encryption where available) you can enable a variety of encryption options for additional security – they offer to encrypt your mailbox on their servers with your login password so that even Posteo can’t read your emails at rest. Or, for even more security, you can opt to have all incoming emails automatically encrypted with your PGP or S/MIME key even if the sender didn’t encrypt them. They also make sure that your payment information is not being connected to your email account so that your email account usage remains pseudonymous.

In my experience, their service is very reliable, fast, and comfortable to use. Only downside (and this is a big one, at least for me): You cannot use your own domain for Posteo! You can choose between a variety of their domains, but you cannot bring your own. This means your email address stays locked-in to Posteo, if you want to move to another provider you will get a new email address that you need to communicate to your contacts. That’s why they only get four stars from me, but if that is not an issue for you, you can’t do much wrong with them.

At its peak, blood testing company Theranos was valued at US$10B, a staggering amount for a privately held start-up. It had raised $700M in investments by venture capitalists and private investors. Theranos founder Elizabeth Holmes was featured on the covers of business magazines sporting a black turtleneck, echoing Steve Jobs’ trademark style. Holmes hobnobbed with the powerful and was celebrated as a brilliant entrepreneur who would revolutionize health-care.

As John Carreyrou recounts in Bad Blood, there was only one problem: Theranos didn’t help people—it hurt them. The company had not created a working product and had systematically deceived the public and investors about this fact, running most tests on recklessly modified commercial analyzers. Worse, Holmes and company president Ramesh “Sunny” Balwani (who was also Holmes’ boyfriend during their time at Theranos) had pushed the company’s flaky blood tests into Walgreens stores.

To minimize regulatory risks, much of this experimentation on human beings took place in the “pro-business” city of Phoenix, Arizona. It had the predictable results: many patients received utterly nonsensical reports that endangered their health and caused them to incur medical debt to pay for expensive follow-up tests.

Climate of Fear

Carreyrou, a Pulitzer-winning investigative writer for the Wall Street Journal whose reporting was instrumental to bringing about the fall of Theranos, tries to explain what happened. Was Theranos a scam from the start? How did things get off the rails?

Holmes, a Stanford dropout, did not understand how the product she wanted could be built—she only knew what she wanted: a slick, compact device that could produce a vast number of different types of blood tests from a tiny sample of blood. Unsurprisingly, her team was not able to deliver what leading scientists and engineers said was an incredibly challenging problem, perhaps unsolvable with today’s technology.

When a normal company fails to achieve an over-ambitious vision, it pivots to a less ambitious one: a larger device, fewer tests, larger quantities of blood. But Theranos was not a normal company. Instead of reasoning through the problem, it fired its internal dissenters, fudged and misrepresented data for investors, and pushed towards the real-world use of extremely flawed, extremely flaky prototype devices.

According to Carreyrou, through much of its existence, Theranos experienced extremely high turnover with frequent and vindictive firings—and resignations in response to dysfunction, intimidation, and ethical transgressions. Employees were first and foremost seen as a threat that had to be monitored (emails and even social media use were heavily policed) and controlled.

An Ineffective, Infatuated Board

The Theranos board included former Secretary of State George P. Shultz, former Secretary of State and war criminal Henry Kissinger, former Secretary of Defense William Perry, and current Secretary of Defense James Mattis. It included no members with substantial relevant expertise and lacked any ability to evaluate the merits of Theranos’ work.

Indeed, the board was infatuated with the Theranos founder and neither able nor willing to hold her to account. Employees who tried to warn the board were ignored or threatened.

George Shultz’s grandson Tyler was exposed to some of the company’s egregious and unethical practices through his own work there. He ultimately blew the whistle on Theranos. However, his attempts to persuade his grandfather that all was not well with the company fell on deaf ears.

The desire to believe that Holmes really was the brilliant and world-changing inventor she presented herself as was all too powerful—and a lot of money was on the line. And it wasn’t just the board that was infatuated; media and investors were all too ready to embrace the Theranos hype without asking too many questions.

Irrational Self-Interest

It took the Wall Street Journal to finally bring down the house of cards. That’s not without its irony; it was the Journal that had granted Elizabeth Holmes an op-ed to promote its company only months earlier, and its owner, Rupert Murdoch, invested $121M in the company just before its downfall. (To his credit, Murdoch never attempted to shut down the Journal’s investigation.)

Problems like the ones Theranos sought to solve—and indeed all problems of similar ambition and scope—require collaboration, transparency, openness. Instead, they were approached with paranoia and secrecy, under cult-like, authoritarian leadership. According to Carreyrou, Elizabeth Holmes told her employees that she was creating a religion.

There is some redemption in Theranos’ ultimate failure, but it’s not the Invisible Hand of the free market that is redeemed, but the role of regulatory bodies (which forced Theranos to discontinue its dangerous tests), of investigative journalists like Carreyrou, of courageous whistleblowers like Tyler Shultz. How much longer could Theranos have survived under slightly different circumstances? How many more people would have been hurt?

The Verdict

Bad Blood does not examine the systemic questions the Theranos case raises, but it is one hell of a story, told by the man who broke it. Carreyrou’s book is based on countless interviews with former employees, partners, consultants, acquaintances; on documents revealed in lawsuits or by whistleblowers; on the scientific papers the company cited, and the opinions of experts.

It reads, for the most part, as if the author had been a fly on the wall during every dramatic turn of the Theranos saga. There is a little bit of repetition as we hear one particular story over and over again—new employee is excited by Holmes’ vision, new employee experiences insane levels of dysfunction, new employee quits or gets fired. There is also a bit more gossip than is necessary to tell the story (Did Elizabeth Holmes fake her deep voice? One former employee thinks so!).

Those are minor criticisms, however. As a story of a fall from grace, of self-delusion, sociopathic behavior and blind ambition, this book is about as good as it gets. Don’t turn here to find out what to learn from the Theranos story. But to begin asking the right questions, it’s a must-read. 4.5 of 5 stars, rounded up.

I’ve long believed in the importance of undercover journalism. As a German, I’m familiar with the work of Günter Wallraff whose riveting report from the inside of Germany’s best-selling tabloid beats Manufacturing Consent any day when it comes to showcasing viscerally how propaganda works under capitalism. But America has had its share of undercover reporting icons, too — from Nellie Bly to Barbara Ehrenreich.

Shane Bauer continues this tradition with American Prison: A Reporter’s Undercover Journey into the Business of Punishment. Bauer (a Mother Jones reporter and former prisoner of the Iranian regime) spent 4 months as a guard at Winn Correctional Center in Louisiana, a for-profit prison. His book is a re-telling of this experience, interwoven with brief chapters about the history of incarceration and forced labour in the United States.

An imprisoned black boy punished at a Georgia convict camp, 1932. (Credit: John L. Spivak. Fair use.)

After the US Civil War, former slaveholders hijacked criminal law to continue “slavery by another name” as Douglas Blackmon put it, with the same profit motives and the same racist ideology serving as pretext. African-Americans were rounded up, often on false pretenses like “vagrancy” or made-up charges, and put to work under the most horrific conditions imaginable.

Bauer explains that the death rates in this late 19th century prison-industrial complex rivaled and exceeded those of Soviet gulags during their worst years. For many of the predominantly African-American convicts, the emancipation of slaves had turned out to be pure fiction—instead, now the corporations “leasing” them didn’t even have any purely financial incentive to keep them alive.

It would take cases of white people like Martin Tabert to force modest reforms. Tabert was arrested on a trivial charge and leased to a lumber company. There, he was brutalized and killed by an overseer. The sheriff who had arrested him was paid a reward for every able body delivered into the hands of the company.

With the rise of mass incarceration in the late 20th century—the new Jim Crow—corporations once again began to see opportunities to derive profit from the caging and exploitation of human beings.

The Winn Report

Bauer’s experience as a Correctional Officer at Winn offers a window into a very different prison system. Here, the goal is not so much to force prisoners to build railroads or harvest timber. It’s to warehouse prisoners at the lowest possible cost, with the greatest possible profit.

The system Bauer describes is one of a chronically under-staffed facility with chronically under-paid and chronically under-qualified staff, where prisoners (when they’re not in segregation) live in open dormitories that house dozens of men. The guards barely manage to keep order.

Literally dozens of shanks—improvised weapons—are discovered routinely; stabbings are frequent and far more common than in publicly run facilities. A thriving underground economy of drugs, phones and sex involves both guards and inmates. The only thing that keeps the whole place from completely falling apart are irregular interventions by “Special Operations” teams from other locations, who attempt pacification by way of pepper spray.

Bauer describes the psychological toll this system takes on him. He (uncritically, which is disappointing) cites the Stanford Prison Experiment, and notes his own changes in behavior—from attempting to form relationships with some inmates, to taking pleasure in acts of revenge against others.

Ultimately, he performs well by the standard of the prison, and is put on the path towards a promotion before he resigns.

The Verdict

American Prison can be difficult to read, given that the entire book is about violence and coercion. There is nothing cathartic here: things haven’t gotten better since the book was published, and the private prison industry is thriving on efforts to cage men, women and children for attempting to seek shelter from brutality and destitution in their home countries.

But it is precisely this kind of reporting that is needed to show—beyond the power of an argument—why the idea of entrusting profit-driven corporations with incarceration is batshit insane.

As a chronicler of this insanity and its historical precursors, Bauer is meticulous. He distinguishes quotes that he was able to capture on audio from those he had to recollect. He provides extensive citations. He identifies the people who gave him permission to use his name. He includes the voices of those who disagree with him. He received appreciation from many of his former colleagues for his reporting.

And that’s precisely the standard that undercover journalism must live up to—especially in a country where garbage-spewing flimflam artists like James O’Keefe have given the genre a bad name.

Bauer is not first and foremost a scholar but a storyteller, and the historical review is relevant and accurate but patchy. Nonetheless, American Prison is a compelling and necessary book. 4.5 points, rounded up.

Desktop thermal transfer printer with UPS Worldship support. These things are reliable, printed several labels a week for a few years after buying it used. Thermal transfer device can get dust on it and need to be wiped off occasionally.

Linux

2020 Update: CUPS has updated and the options below are no longer necessary. Simply setup with EPL2 driver and go.

Old info:

Linux support is frustating but completely fixable. The printer will print out of the box with Zebra ZPL print driver. The prints will look poor and barcodes will be terrible and likely unreadable. The fix is to use the CenterOfPixel option when printing :

lpr -P printer -o CenterOfPixel pathtofile.

Prints will look just like they do on Windows. You can add this option as default in the .ppd file in /etc/cups/ppd for this printer by adding

*OpenUI *CenterOfPixel/Center Of Pixel: PickOne

*OrderDependency: 20 AnySetup *CenterOfPixel

*DefaultCenterOfPixel: true

*CenterOfPixel true/true: “”

*CenterOfPixel false/false: “”

*CloseUI: *CenterOfPixel

to the .ppd file.

/oldinfo

UPS

Printing UPS labels from a browser using UPS Thermal Printing Script requires the printer is setup with a raw queue. When adding the printer, click on generic driver then raw. Print normally and the script will take care of the rest. Label prints perfectly.

Verdict

Printer is dead reliable, supported by Linux

I was looking for new sports headphones and after reading the reviews on Amazon which compared those “Mpow” headphones favourably to the Beats Powerbeats line I thought I would give them a try - at 30 CAD they are really cheap.

I have never tried the Beats headphones, but if they are really comparable to these this is not a great endorsement for the Beats line. First, the good: They fit well, don’t fall off and pairing works well. Battery power is sufficient for a longer run. But sound quality is pretty mediocre (and I am not a hi-fi connoisseur). If you don’t need Bluetooth, you are (in my opinion) better off to get similarly priced headphones with a cable connection which will have much better sound quality.

In Unthinkable: What the World’s Most Extraordinary Brains Can Teach Us About Our Own, science journalist Helen Thomson chronicles her meetings and interactions with a set of people whose minds have unusual qualities, e.g.:

-

one subject hyper-empathizes with the emotions he sees in others, experiencing touch and pain almost physically;

-

another, for some time, was utterly convinced that he was dead;

-

one remembers nearly every day of her life in vivid detail;

-

another sees auras around people, reflecting his own feelings about them.

Thomson interweaves these stories with neurological research and short “here’s a thing you can try at home right now” experiments, some more practical than others. From each episode, she tries to draw conclusions that can apply to many of us—about how our memory really works, or how to manage our own empathy.

The science here is light reading, and sometimes too light; for example, while Thomson spends a couple of paragraphs debunking popular misconceptions about “left brains” and “right brains”, she quickly embraces “top brain / bottom brain” theory as an alternative explanatory model, without applying similar skepticism.

Overall, though, Unthinkable is a quick and entertaining read that personalizes a complex subject through a necessarily arbitrary but interesting cast of characters. 3.5 out of 5 stars, rounded down because each of these stories would have deserved a bit more depth than Thomson gives them.

Current Affairs is a left-wing magazine (review) and podcast, and they publish some of their essays in book form as well. I received one such collection, “The Current Affairs Mindset”, as a Patreon gift for supporting the podcast. Since I’ve only subscribed to the magazine since 2018, this was a welcome gift; the book was published in 2017 and includes essays from the 2016-2017 time period.

The cover is adorned with an illustration of a middle-aged, mildly obese white man admiring himself in the mirror, pretending that he is a gorilla with a Trump-like head of blond hair. The title and illustration poke fun at far-right demagogue slash self-help guru Mike Cernovich’s “Gorilla Mindset” cult, which is dissected in one of the book’s better essays.

The cover and the brevity of most essays also make the book a decent bathroom reader for any lefty household. Because Current Affairs doesn’t paywall its content, you’ll find all of the included essays online, as well, in case you want to sample the content on a screen before buying a print version.

Complete table of contents with links

Politics

- Slavery is Everywhere by Brianna Rennix and Oren Nimni

-

The Pathologies of Privilege by Zach Wehrwein

-

The Necessity of Political Vulgarity by Amber A’Lee Frost

-

What Does Free Speech Require? by Eli Massey

-

How Identity Became a Weapon Against the Left by Briahna Gray

-

Riding the Hashtag by Yasmin Nair

-

More Lawyers, Same Injustice by Oren Nimni

-

Pretending It Isn’t There by Nathan Robinson

-

The Scourge of Self-Flagellating Politics by Angela Nagle

-

At the Border by Brianna Rennix

Culture

-

Peculiarities of the Yankee Confederate by Alex Nichols

-

Suicide and the American Dream by Nathan Robinson

-

The Cinema of 9/11 by Felix Biedermann

-

The Great American Chemtrail by Angela Nagle

-

The Unendurable Horrors of Leadership Camp by Eric Fink

-

Why Journalists Love Twitter by Emily Robinson

-

You Should Be Terrified That People Who Like “Hamilton” Run Our Country by Alex Nichols

-

Against Domesticity by Amber A’Lee Frost

-

How Liberals Fell in Love With The West Wing by Luke Savage

People

-

Finding Your Inner Gorilla by Brianna Rennix and Nathan Robinson (about Mike Cernovich)

-

I Don’t Care How Good His Paintings Are, He Still Belongs in Prison by Nathan Robinson (about George W. Bush)

-

Killing You Softly with Her Dreams by Yasmin Nair (about Arianna Huffington)

-

The Rise of the Ruth Bader Ginsburg Cult by David Kinder

-

The Real Obama by Nathan Robinson and Luke Savage

They range from left-wing critiques of liberal obsessions (like the musical Hamilton) to very cogent analysis of the resurgence of the far-right, and of the realities of poverty and oppression in the United States.

While parts of the book feel a bit echo-chambery (“here’s what good lefties think about X”), Current Affairs deserves credit for publishing nuanced essays on topics like free speech or identity politics, instead of embracing received wisdom of any particular political persuasion.

How much do you know about the overthrow of the Kingdom of Hawaii, about the Philippine-American War, about America’s efforts to depose José Zelaya in Nicaragua, Jacobo Árbenz in Guatemala, Mohammed Mossadegh in Iran, and Ngo Dinh Diem in South Vietnam? If the answer is “very little”, Stephen Kinzer’s 2006 book Overthrow remains a reasonable introduction to these and other “regime change” efforts.

Kinzer, a journalist and writer who was the New York Times correspondent for Central America in the 1980s, weaves a narrative of some of America’s military and intelligence interventions in other countries from the late 19th century to the early 21st. He connects the political events with the stories of some of the key figures involved, like Henry Cabot Lodge and his grandson, Theodore Roosevelt, and the Dulles brothers—John and Allen, subject of another book by Kinzer.

Throughout his analysis, Kinzer points at the clear commercial interests at the root of foreign policy interventions: taking control of Hawaii at the request of American-born plantation owners, preserving United Fruit’s corporate stranglehold over Guatemala, punishing Iran’s Mossadegh for attempting to end foreign exploitation of the country’s oil reserves.

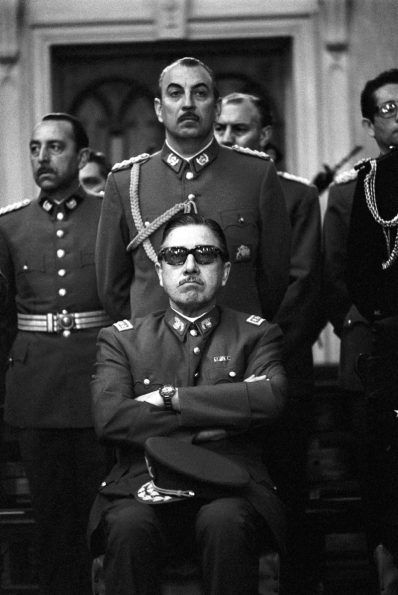

After a directive from Richard Nixon to “make the economy scream” through sabotage, the CIA used the subsequent instability to help install Augusto Pinochet, replacing Chile’s democratically elected leader, Salvador Allende. Pinochet’s regime was responsible for the death of thousands, and for the arrest and torture of tens of thousands. (Credit: Chas Gerretsen. Fair use.)

The typical pattern of each chapter is “storytelling → larger political events → analysis”. As a storyteller, Kinzer is not quite at the level of Erik Larson—there are some slightly jarring repetitions, for example—but the book is certainly engaging.

The book’s value is ultimately limited by its narrow scope, and by its unwillingness to stray too far outside the Overton window of American political discourse. For example, America’s many efforts to influence democratic elections in other countries help to understand why democracy and political independence are often difficult to reconcile for smaller countries.

But these efforts, far more numerous than direct intervention, are largely out of scope, as are many of the other methods America’s military and intelligence apparatus have employed (and continue to employ) to bolster friendly regimes, however brutal, and to undermine perceived unfriendly ones.

When Kinzer imagines “what-ifs” for countries like Guatemala and Nicaragua, he theorizes that America stunted the emergence of independent capitalist democracies. In full cognition of the historical facts, it should not take much daring to speculate whether democracy and capitalism are in fact compatible at all.

The book’s narrative ends with the near-term effects of George W. Bush’s war in Afghanistan and Iraq. Kinzer’s 2006 prognosis for both countries was not optimistic; today, one would have to connect the dots between these interventions, subsequent American and European actions in the region, and the terror, wars and instability that continue to this day.

I recommend Kinzer’s book with the above reservations as a starting point to explore America’s imperialist history. It may also serve as a cautious introduction for readers wary of more radical authors like Chomsky (who eloquently critiqued Kinzer’s New York Times reports from Central America in the 1980s). 3.5 of 5 stars, rounded up because of the importance of the subject and the quality of the writing.

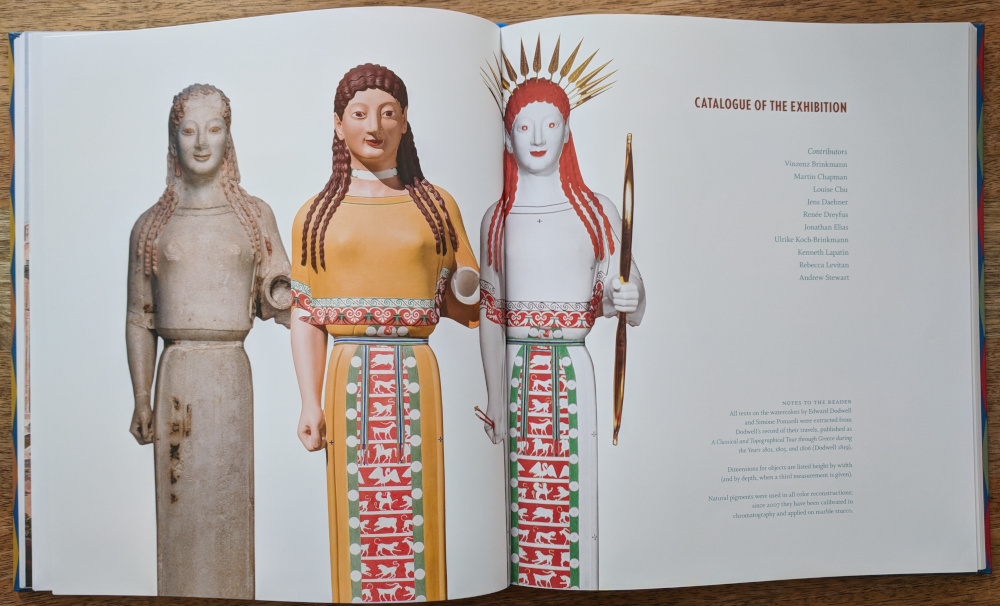

Ancient statues and buildings were frequently painted in vivid colors. The modern image of austere white marble is largely an invention, based on misunderstanding the weathered appearance of ancient works as intentional. That invention became the preferred view of antiquity from the Renaissance to today.

Ancient polychromy is not, however, a recent discovery. After all, statues often still had pigments on them when they were discovered (many still do so today). Historians like Johann Winckelmann (1717-1768) acknowledged that many ancient statues were colored, but claimed that “the whiter the body is, the more beautiful it is.”

The true colors of the ancient world reflect the diversity of the people that inhabited it. They also make the ancient West look a lot more like the ancient East, offering a glimpse at the thread that connects all humanity; sharpening the contrast between the polytheistic, messy culture of ancient Rome and the darkening age that followed it.

Since Winckelmann, historians have rarely embraced, sometimes rejected and mostly ignored the true colors of antiquity. In recent decades, a small number of archaeologists and historians have tried to change that, culminating in an exhibition of painted statues called Gods in Color which first opened 2003 and has been continuously updated since then. The book Gods in Color: Polychromy in the Ancient World is a catalog of the exhibition with some additional essays on the subject.

Reconstruction of the Peplos Kore as featured in the book. (Credit: Gods in Color. Fair use.)

The introductory essays are short but interesting, shedding light on the discovery and perception of ancient polychromy, and giving examples of early drawings and reconstructions.

The new reconstructions, however, may offend modern sensibilities. This is less because they’re colorful and more because they just are not very well done. As Margaret Talbot writes in the excellent New Yorker article “The Myth of Whiteness in Classical Sculpture”:

In the nineteen-nineties, [Vincent] Brinkmann and his wife, Ulrike Koch-Brinkmann, who is an art historian and an archeologist, began re-creating Greek and Roman sculptures in plaster, painted with an approximation of their original colors. Palettes were determined by identifying specks of remaining pigment, and by studying “shadows”—minute surface variations that betray the type of paint applied to the stone. The result of this effort was a touring exhibition called “Gods in Color”.

(…)

But [Mark] Abbe, like many scholars I talked to, wasn’t crazy about the reconstructions in “Gods in Color.” He found the hues too flat and opaque, and noted that plaster, which most of the replicas are made from, absorbs paint in a way that marble does not. He was also bothered by the fact that the statues “all look fundamentally the same, whereas styles would have differed enormously.”

All of this is true. Moreover, many of the depicted reconstructions are incomplete, with partially colored eyes or limbs creating a truly garish appearance. Where the original is damaged, so is the replica, with a white broken nose at the center of a flatly painted plaster reconstruction.

The pigments recovered from each original are carefully documented, but the artistic execution of most of the reconstructions is accordingly mechanistic, constrained by evidence that remains between us and the ancient world.

The result is a presentation of antiquity in painted plaster that resembles the uncanny valley of bad computer graphics. The Brinkmanns and their collaborators deserve the world’s credit for forcing us to take a more realistic view of the ancient world in its full color—but a lot of work remains to do so in style.