Latest reviews

O espaço é lindo, o cardápio é todo vegano, a atmosfera é muito boa… mas infelizmente o atendimento deixa a desejar. Pedimos hambúrgueres e depois de 40 minutos, fomos falar com a garçonete, que disse que havia esquecido do pedido, e a cozinha já estava fechada. No fim acabaram fazendo (sem porção de batata que acompanha) e não nos cobraram, mas foi uma experiência muito ruim. Conversando com amigos, parece que não é a primeira vez que isso acontece. É uma pena, estou torcendo para que melhore porque é um lugar com muito potencial!

Dito isso, a comida é gostosa (talvez falte um pouco de sal pro meu paladar) e a variedade no cardápio é muito boa. Experimente a coxinha! Apesar do ocorrido, eu sinto que voltaria para comer aqui.

In Humanizing the Economy: Co-operatives in the Age of Capital, John Restakis, a veteran of the Canadian co-op movement, argues for increasing the role of co-operatives and economic democracy, without suggesting that they are a panacea.

Restakis’ argument is firmly grounded in a critique of corporate capitalism; the 2007-2008 financial crisis still loomed very large when the book was published. But Restakis is also highly critical of the disastrous and dehumanizing effects of authoritarian systems with centralized, planned economies.

Instead, much of the book comprises case studies of co-operative economics:

-

the region of Emilia-Romagna in Northeast Italy, where thousands of co-operatives thrive and nearly two out of three citizens are members of co-ops;

-

the fábricas recuperadas (recovered factory) movement in Argentina, a system of co-operative self-management of factories which followed the country’s economic crisis in 2001;

-

the sex worker collectives in India, such as Durbar, a collective of over 65,000 sex workers that combines mutual aid and social services to its members with political advocacy;

-

the Japanese system of consumer co-operatives with more than 28 million members, which provide services such as home delivery, while also incorporating ethical sourcing practices and promoting organic produce;

-

the global movement for fair trade and its sometimes rocky relationship with the co-operative approach.

Unless you’re steeped in the history of co-operatives, it’s quite likely that you’ll find remarkable examples you’ve never heard of. It’s rare for the narrative in conventional Western media to look at examples like these; when there is reporting about economic matters, it’s mostly about whether this or that elected leader will be “business-friendly” and “convince the markets”.

Restakis challenges this thinking about markets as an implacable, amoral force of nature and instead argues that markets are what we make them. An economy that places shared human concerns at its center (and that de-emphasizes the profit motive and the advancement of the individual) is not only possible—it’s one that hundreds of millions of people already participate in.

Members of the Durbar collective of sex workers march against violence and trafficking in Kolkata in 2018. Durbar provides services to sex workers, fights for legalization of sex work, and combats human rights violaitons. (Credit: India Blooms. Fair use.)

Ideas Vs. Ideology

The ideology of corporate capitalism is just that: an ideology that is taught in schools and universities, in media depictions of success and failure, in its self-advertisements. Corporate capitalism also enjoys massive subsidies, including the planet-wide subsidy of tolerating the destruction of the environment instead of taxing it.

Restakis notes that governments have a choice: to continue to underwrite this ideology without question—or to shift resources towards promoting co-operative economics. This kind of support can range from teaching how to run a business co-operatively, to establishing tax incentives, to setting up resource centers (as was done in Emilia Romagna) that provide administrative support to help co-ops succeed.

It’s not as distant a possibility as it may seem. For example, Jeremy Corbyn’s political platform combines nationalization in some areas of the economy with heavy support for the co-op model and workplace democracy in others.

The Verdict

Restakis frontloads his most radical criticisms of corporate capitalism to the early chapters of his book. Humanizing the Economy is a case for incorporating the co-operative model into economic thinking, without offering a blueprint how to do that, or even suggesting that it should be the dominant model of the economy.

For the most part, the author succeeds in making this argument. Given that the book significantly relies on data (numbers of factories recovered in Argentina; numbers of employees in the co-operative sectors of Italy, Spain or Japan; success of credit unions during the financial crisis, etc.), it is disappointing that there is not a single chart or table in the book.

For a book written in 2010, I would also have appreciated more insights into how the Internet enables new forms of cooperation and sharing. Fortunately, other authors have since filled this void, such as Trebor Scholz and Nathan Schneider with “Ours to Hack and to Own: The Rise of Platform Cooperativism”.

As someone still learning about co-operative practices and the solidarity economy, I found John Restakis’ book a useful wayfinder to a lot of examples that I will likely keep coming back to. If you are looking for similar inspiration, I recommend this book.

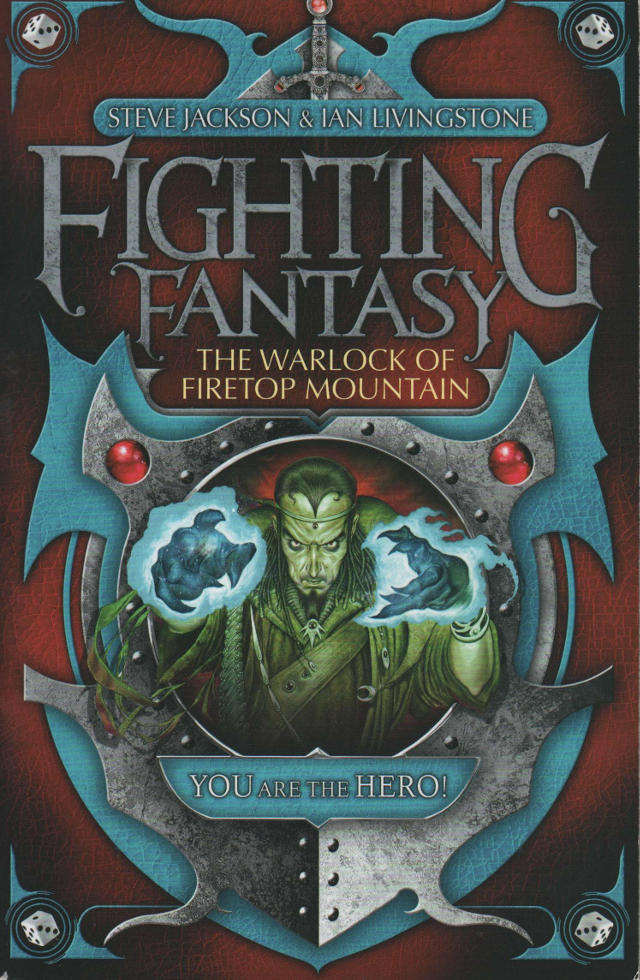

The Warlock of Firetop Mountain written by Steve Jackson (UK) and Ian Livingstone is the first title in the Fighting Fantasy (FF) gamebook series. Published in 1982 it was such a great success that nearly 60 titles in the series followed. As the very first book it also works as a blueprint for many other books in the series. This includes the arbitrary limit of 400 sections and dungeon crawling in a fantasy setting.

The title spells most of the back story already. YOU are an adventurer that tries to find the treasures of the warlock Zargor in the firetop mountain. Those are hidden in a maze in subterranean halls of the mountain. The game mechanics are easy to learn. The requirements are low as everybody has a pen and paper. On the bottom of the pages are the required dices printed even though most readers will likely raid the family board game collection to get some actual dice. This low entry barrier is to this day key for the series’ success.

Cover by Martin McKenna of the Wizards Series #1 (Credit: Martin McKenna, Wizards Books. Fair use.)

The gameplay consists of stat keep of the character and their inventory. Tests of luck and combat situations are resolved with just the two dices. The monster encounters are quick fights that give the flow of the book a nice pace between action and exploring.

All classical flaws that haunt the FF series are present like roll or die scenarios where bad luck just ends the adventure. Dead ends like missing one of the required keys also ends the journey while the player did nothing wrong. The dungeon itself is engaging and well described so that map drawing is fairly easy. Finding a low risk route is done by trial and error to finally get the treasures of the warlock. After you found the treasures the replay, value is nil.

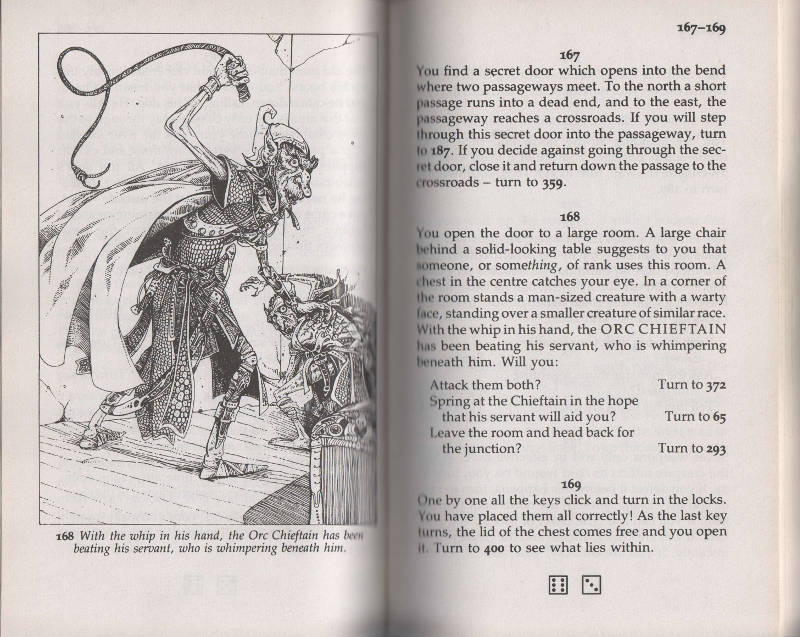

The Warlock of Firetop Mountain is a classic and a great introduction to the gamebook genre to this day. Instead of world building it focuses on the gameplay. The atmosphere and flair comes from the great black and white illustrations by Russ Nicholson which more than compensate the missing world building in the text. Many reprints and translations for the very first FF adventure are available so everybody has a good chance to read a well recommended classic.

Interior pages with illustration (Own work. License: CC-BY-SA.)

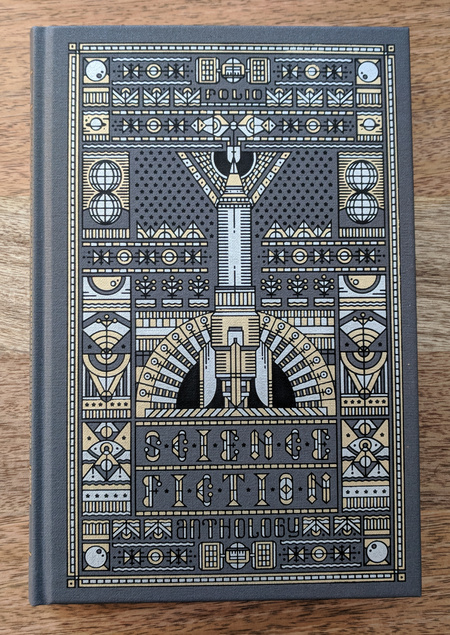

Many sci-fi readers will recognize the name Brian Aldiss (1925–2017), both from his own stories and novels, and from the many anthologies he compiled. The first, for Penguin Science Fiction, was published in 1961. This one is the last, and it is also Aldiss’ final published work. It was published by the Folio Society, which specializes in expensive but beautiful editions of many classic and contemporary works, and which also publishes original anthologies such as this one.

The packaging

You won’t find this book on Amazon, and it is currently advertised at USD 53.95—a hefty price for a single volume. But that’s the Folio way—these are books for bibliophiles, whether that describes yourself or someone you care about. The cover, in this case, is block printed on buckram (cloth) and features a beautiful abstract illustration of a rocketship:

Cover for the Folio Society Science Fiction Anthology (Credit: Folio Society / own photograph. Fair use.)

It’s a pleasure to hold this book and to examine the detail of the print:

Detail of Folio Society Science Fiction Anthology book cover (Credit: Folio Society / own photograph. Fair use.)

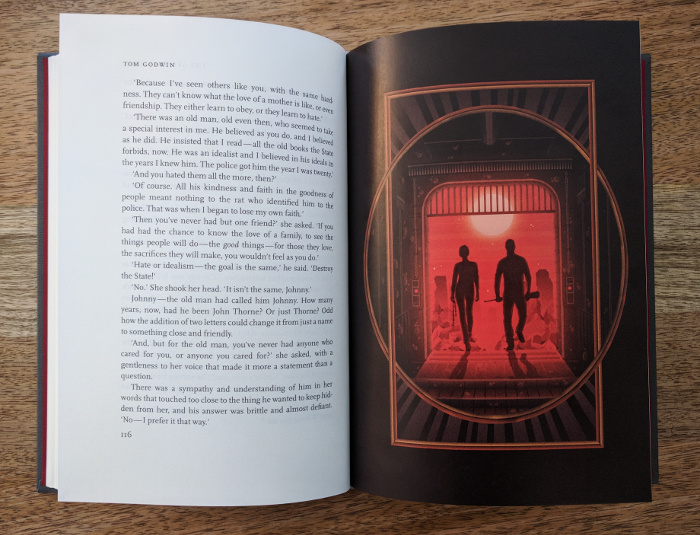

The book comes with a slipcase cover, which looks more stylish than a typical dust cover, and doesn’t get in the way while reading. Like many Folio books, the anthology features commissioned illustrations for several of the stories in the anthology:

Pages from Folio Society Science Fiction Anthology. (Credit: Folio Society. Fair use.)

The stories

The stories are arranged in chronological order. They are:

-

Micromégas by Voltaire (1752)

-

The Star by H.G. Wells (1897)

-

Bridle and Saddle by Isaac Asimov (1942)

-

The Greater Thing by Tom Godwin (1954)

-

Grandpa by James H. Schmitz (1955)

-

Poor Little Warrior! by Brian Aldiss (1959)

-

Recall Mechanism by Philip K. Dick (1959)

-

An Alien Agony by Harry Harrison (1962)

-

Searchlight by Robert Heinlein (1962)

-

Clarita by Anna Kavan (1970)

-

And I Awoke and Found Me Here on the Cold Hill’s Side by James Tiptree Jr., pen name of Alice Sheldon (1972)

-

The Day They Raised the Titanic by Alice Wilson (2015)

As is evident from this list, there is only one recent story, and many are from around the Golden Age of sci-fi—don’t expect to find tales of posthuman existence or hard sci-fi grounded in our current knowledge of space travel and planetary exploration. That said, I found several of the stories quite stimulating:

-

Bridle and Saddle—this story is part of Asimov’s Foundation saga, but requires no familiarity with it. The administrator of a lightly populated planet that exercises centralized control over all knowledge on behalf of a multi-planetary society is faced with threats from the planet’s powerful neighbors, and from discontents at home. Will he be able to hold onto power without violence, which he calls “the last refuge of the incompetent”?

-

Grandpa—a kid who is part of a colonization team stewards a small expedition on a large lily-pad-shaped hybrid plant/animal called “Grandpa”. Grandpa, it turns out, is not quite as simplistic a creature as everyone thought, and our protagonist has to find a way out of an increasingly desperate situation. Although more than 60 years old, there’s nothing in this story that dates it to its era.

-

An Alien Agony—science and religion clash on a planet that has very little experience with either. A beautiful little “loss of innocence” story.

-

And I Awoke and Found Me Here on the Cold Hill’s Side—this story caught me by surprise in that I’ve never encountered its premise before: that humans are uniquely attracted to aliens (both sexually and in terms of pure curiosity), while other species find this behavior very amusing. A story that explores xenophobia and xenophilia, and makes you think about what alien encounters would actually be like.

The illustrations by Florian Schommer stylistically follow the books’s chronology (“as the stories move towards the modern age a palette of deep oranges and reds is gradually introduced”, to quote Folio’s description), and the polygons and circles that frame each picture make them look like windows into different worlds.

The Verdict

I quite enjoyed about half the stories in the volume, and some of them (like Grandpa) are true gems of the genre. As with every Folio Society book I have the pleasure to own, this is a beautifully made physical object. It is also a lovely gift for any sci-fi lover. 3.5 stars, rounded up because of the appreciation of the book as an object that endures in Folio’s publications.

Life’s Lottery by Kim Newman works like a classic Choose Your Own Adventure book but with an adult story in a real world scenario. It explores how little, seemingly unimportant decisions can steer the life of the protagonist. There is no stat keeping or dice cast necessary to follow the life of Keith Marion from childhood to death. A minor childhood decision can derail his adulthood from happiness to misery which gives the reader great pleasure because it allows messing with someone’s life.

Every decision asks if Keith actually has a choice when you know all details from his life to this moment. Even worse, some events are inevitable baring the question: Is there any choice in life or is it just predestined? The plot handles all aspects of life like confronting the school bully, losing the love of your life or a criminal career.

Book cover (Credit: Titanbooks. Fair use.)

The multiple endings of the story vary a lot so the replay value is high. But it is more about back tracking and re-reading sections to nudge destiny in the right direction instead of re-reading the whole story again. In the book are no illustrations so it feels and looks a bit dry. I recommend reading Life’s Lottery because it strays from the sucked dry fantasy setting to a rare real world setting. The adult themes are a refreshing change from the common gamebook stories.

This game is one of the biggest mistakes you can make. After playing it you will be bored of the most other games.

It’s just so incredibly good, detailed to the last bit, with huge amount of content and far-reaching concequences of player choices. Graphics and sound are amazing. Both main and secondary quests are of top quality. Witcher contracts can be a bit repeatable, but stay complex and interesting nevertheless. The story is also very exciting and as a fan of the Witcher series (also the books) it fits perfectly into the universe that mixes the dark middle ages with fantasy. But you can play this game even if you have never played The Witcher before or read one of the books.

The most distinguishing feature in The Witcher 3 is that it offers us a completely living world (one of the biggest I’ve ever seen). In this world dynamic weather conditions, day and night cycle and active economic ties add a whole new color to the game.

In the end I would say that The Witcher 3: Wild Hunt is a game that can be played many times (although a playthrough takes 200 hrs.) and offers an adventure that you cannot stop playing the game for hours. If you have a special interest in RPG games, or if you are interested in starting these kinds of games, then this game should definitely be The Witcher 3: Wild Hunt.

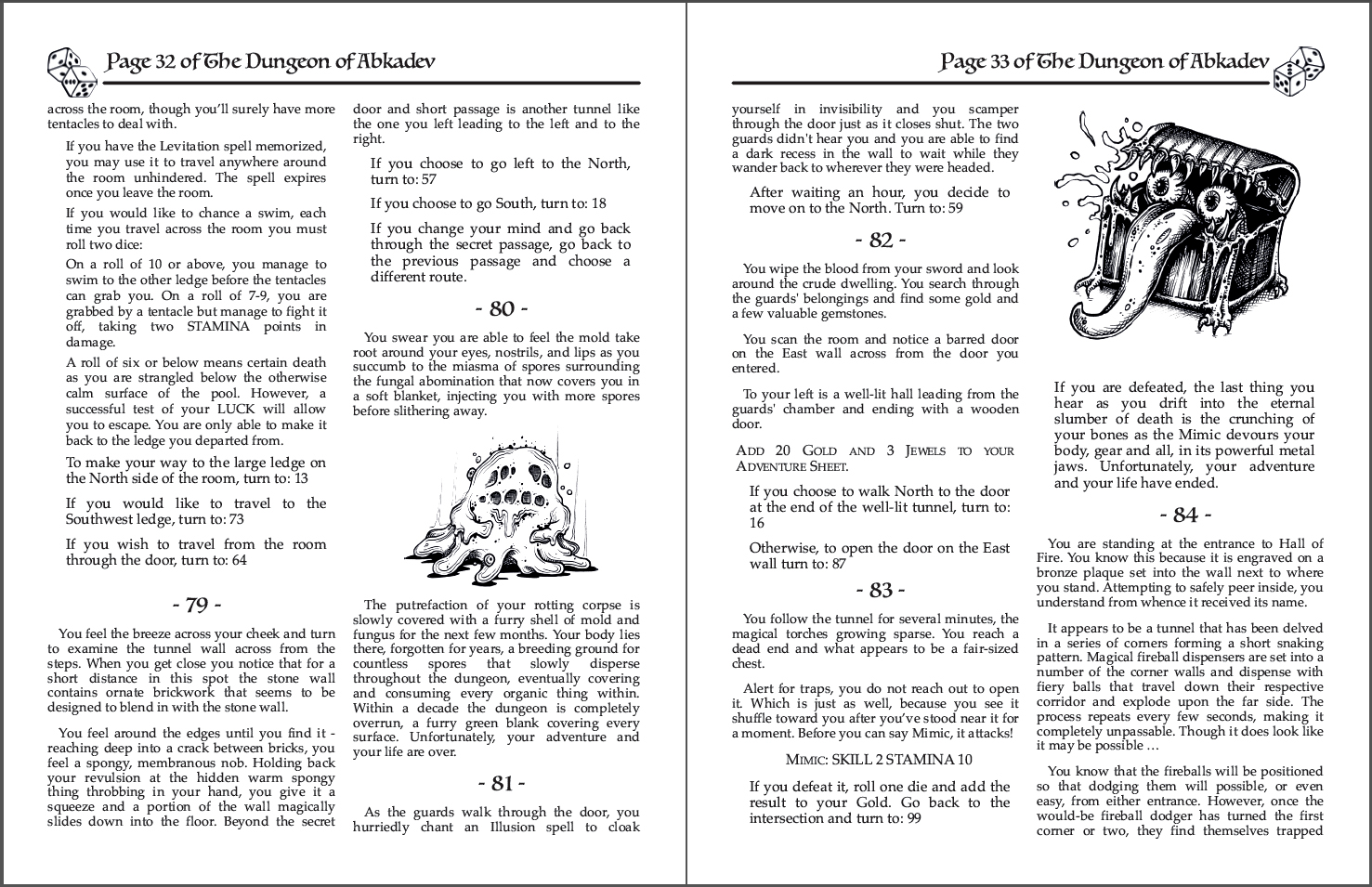

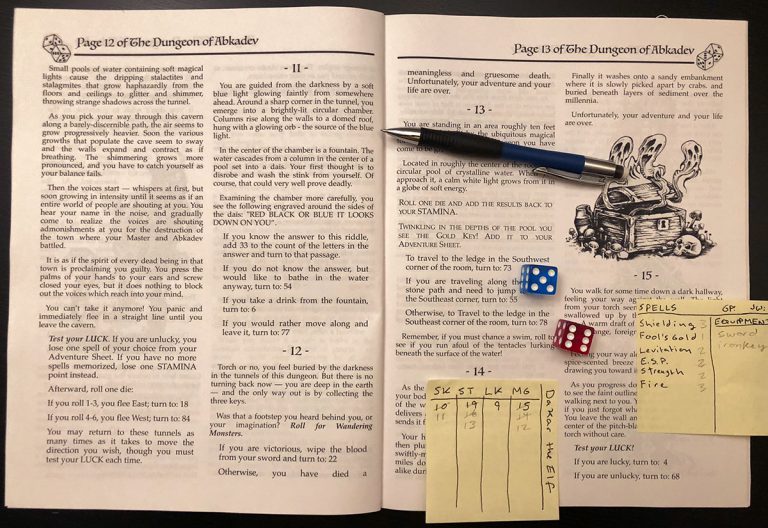

The Dungeon of Abkadev by Peter Konink is a Print & Play Adventure that closely mimics the gameplay of the Fighting Fantasy (FF) gamebook series. This adventure is based on the winning One-Page Dungeon 2016 of the same name.

The rules are very similar, including the magic, to the rules of the classic Citadel of Chaos which is the second in the FF series. Classic game mechanics are extended with random wandering monsters and the abstinence of roll or die situations. If you played any of those books before then you will understand it very quickly.

View inside the PDF file. (Credit: Pieter Konink. Fair use.)

While the story places you in the aftermath of a massive battle between two mighty wizards, the actual gameplay is just one big dungeon. You explore the dungeon to find the Tome of Vyzx for your wizard master. Even though the adventure consists only of 100 sections you get everything from monsters, traps, riddles to map drawing. The difficulty is high as it is impossible to obtain all three keys on the first try. Knowing traps and encounters before hand will help you to select the better routes and fitting magic spell. If you do not get all keys it is better to restart the adventure as back tracking is very tedious. Once you have collected all keys and finished the adventure there is little replay value.

The adventure contains several good illustrations that enrich the atmosphere. Together with the good layout and type setting the adventure looks really good when printed out at home. Dungeon of Abkadev is a great dungeon crawler every FF-fan should play.

Printed copy, used for playing (Credit: Pieter Konink. Fair use.)

Triumph of Christianity over Paganism. 16th century fresco by Tommaso Laureti decorating the ceiling of the Constantine Hall in the Vatican Palace. (Credit: Jean-Pol GRANDMONT. License: CC-BY-SA.)

From the comfortable distance of a privileged life in the 21st century, it is perhaps easy to see that the Roman Empire was doomed. Having replaced oligarchy with permanent dictatorship, the empire sustained its ambitious civilization-building effort through slave labor and the spoils of expansionist wars. Internal unrest and foreign invasions were sure to follow. What role did religion play in this collapse?

Catherine Nixey’s book, The Darkening Age, makes the case that Christianity added fuel to the fire: quite literally in the form of book burnings or the melting down of statues, and figuratively through its embrace of a fanatical, exclusionary belief system that made it impossible to re-build or preserve a crumbling society.

Nixey knows her stuff; she studied Classics at Cambridge and subsequently worked as a Classics teacher for several years, but she is first and foremost a journalist, and her book tells history much in the way a writer like Erik Larson does: as a story with characters, sometimes picking the source that best fits the narrative, rather than attempting a neutral presentation of all possibilities of what happened.

In evidence of her thesis, Nixey marshals both “pagan” and Christian primary sources and cites recent modern research, such as Eberhard Sauer’s The Archaeology of Religious Hatred (Tempus, 2003) and Dirk Rohmann’s Christianity, Book-Burning and Censorship in Late Antiquity: Studies in Text Transmission (De Gruyter, 2016). The key themes of her book can be summarized as follows:

-

Early Christianity was a fanatical religion focused on martyrdom, suffering, and death.

-

While Christians were certainly persecuted at various times, the extent of that persecution was dramatically exaggerated.

-

As Christians gained power, they turned the tables and engaged in systematic destructions of temples, statues, and books, and forced conversion through acts of terror and murder.

-

The church did play an important role preserving what little ancient knowledge was preserved — but it did so extremely selectively (omitting materials considered too salacious, or those seen to contradict Christian doctrine). Effectively, much of the earlier culture was annihilated, including irreplaceable philosophical and scientific texts.

-

Rome’s polytheistic culture was sexually permissive and tolerant of argument and debate. Christian writers, in contrast, replaced debate with dogma. They railed against the “tyranny of joy” and laid the foundation for centuries of Christian sexual repression, associating pleasure with shame in ways that reverberate to this day.

You may think there is a consensus among modern historians about these claims, but there is not (this is, after all, a society still rooted in the very origins that are at issue). As Nixey acknowledges, many historians have painted a very different picture. Today you’re just as likely to read that polytheism simply grew out of fashion, or that the Dark Ages “weren’t really dark”, or that Christianity was a benign and civilizing influence during a chaotic time. Don’t even think to draw modern parallels!

Yet, as Nixey demonstrates, those parallels are all too obvious, and they are instructive, which is indeed why apologists prefer to ignore them. Nixey points out that Christian statue-smashers defaced the same beautiful statue of Athena at Palmyra that ISIS would completely obliterate more than a millennium and a half later, with similar “reasoning” (“The Prophet Muhammad commanded us to shatter and destroy statues.”).

Apologists claim that when early Christians burned books about “sorcery”, surely they contained just that—not science or philosophy! But we find no such nuance when we look to modern claims of “sorcery” by religious fanatics, such as when the Taliban sacked Afghanistan’s Meteorological Authority in 1996 because weather forecasting is, of course, sorcery. Christian fanatics who call Harry Potter “Witchcraft Repackaged” don’t draw the distinction between literature and religion.

Just as it did not in ancient Rome, tolerance rarely lasts long after religions gain political power. In the United States, where evangelical Christianity still has somewhat of an underdog status, religious extremists who oppose evolutionary theory merely ask that schools and universities “teach the controversy” (while funneling taxpayer funds to schools that teach only creationism). In Turkey, where Islamists have substantial political power, evolutionary theory was recently banned from textbooks.

In short, the counterarguments to Nixey’s thesis fall apart precisely when one observes and compares religious fanaticism in any of its modern manifestations that are more easily studied than texts from the 4th or 5th century (and less subject to manipulation, omission, and re-interpretation over the centuries). The fanaticism Nixey describes is, sadly, far from unique or remarkable, and its intellectual legacy is still with us today.

Learning from collapse

In The Queen of Spades, a short story with supernatural overtones, Alexander Pushkin wrote: “Two fixed ideas can no more exist together in the moral world than two bodies can occupy one and the same place in the physical world.“ By that standard, two ideas could not be more fixed than those of polytheism and monotheism. How does one tolerate the intolerant?

Christianity was not the only cult of its time that made singular claims to the truth; it was merely the one that ultimately prevailed. But far from being a force for peace or preservation, it added fuel to the fire of Rome’s—probably inevitable—collapse.

A fierce, hateful religion (and that is what this iteration of Christianity was) could never have gained such momentum in a healthy, stable society. But under conditions of instability and inequality, it accelerated and ultimately cemented the loss of a civilization. That is the key lesson to carry into the 21st century, and Nixey deserves much credit for writing an accessible book to do so.

Can you Brexit? is a rare genre mix of political satire and gamebook by the well-known Dave Morris and Jamie Thomson. The duo is known for the Fabled Lands gamebook series and more.

Book Cover (Credit: Dave Morris and Jamie Thomson. Fair use.)

The book puts the reader in the shoes of the Prime Minister (PM) of the United Kingdom first day after the Brexit vote till the bitter very end of the Brexit process. At least basic knowledge of the UK or the EU is required to follow the story even though the books goes into great length to explain the actual problems that need to be handled. These include the National Health Service (NHS), Exit Fee, Immigration, EU Trade Talks and Residency Rights. As PM, you cannot decide everything as you like. You have to consider not only the facts but also have to delegate decision-making, respect the party and popular opinion. The books make it very clear that this is the worst job you can have in current Europe.

While the actual Brexit is not yet the complete, the book allows the reader to follow alternative paths and already finish the Brexit in an alternative reality. For this alternative reality all names of political figures have been replaced with somewhat funny names. Everything is in the cards for the reader including political suicide to great disaster for Britain. As long as the real Brexit isn’t over, the replay value is high as you can play it again with current political progress in mind. The overall presentation is very dry with no illustrations. The gameplay requires keeping track of certain decisions and results in a lot or check boxes. No deice are required but a seldom coin toss will decide for you. The outcome of the story is base on four stats: Authority within the party, Economy of Britain, Goodwill of the EU and Popularity with the voters. Those can be increased with good decisions and very easily lost with any kind of backlash.

Can you Brexit without breaking Britain? It’s a difficult task and the book gives a very good glimpse into the process and facts behind the decision-making. It also makes very clear that Theresa May has the worst job any politician. Reading her memoirs and comparing it with these books a few years will be the only reason to replay it after Brexit. This book is for the political interested gamebook fans. For a gamebook beginner the story and presentation can be too dry to enjoy it at first.

Mit Flucht aus dem Dunkel entsteht 1984 der erste Band der Spielbuch-Reihe Einsamer Wolf von Joe Dever. Sie ist mit 10 Millionen verkauften Büchern ein der erfolgreichsten Solo-Abenteuer-Serien weltweit. Die hier vorliegende und erweiterte Neuauflage erscheint beim Mantikore-Verlag und unterscheidet sich deutlich von der Urfassung. Um an diesem Solo-Abenteuer Spaß zu haben, braucht man außer dem Buch selbst nur einen Bleistift und Radiergummi.

Bild des Buchs (Eigenes Werk. Lizenz: CC-BY-SA.)

Der Leser beginnt sein Abenteuer direkt mit dem Angriff der Schwarzen Lords auf die Abtei der Kai. In der Urfassung beginnt das Abenteuer erst nach der Zerstörung der Abtei und lässt den Leser im Unklaren über die grausamen Geschehnisse dort, die so in der Fantasie des Lesers stattfanden. Jetzt dient der Angriff als ein actionreicher Einstieg in die Fantasy-Sage und möglicherweise in das Medium der Spielbücher selbst. Der Ausgang ist vorgegeben, wie man sich in der Schlacht anstellt, ist der spannende Teil für den Spieler. Man reitet, kämpft und klettert durch die Abtei und macht sich mit den Mechaniken des Spielsystems vertraut. Dazu gehören Kämpfe, verwalten des Inventars und Kai-Fähigkeiten einsetzen.

Der Weg von der zerstörten Abtei dann hin zum König in Holmgard verlangt richtige Entscheidungen, um Erfolg zu haben. Fallen müssen erkannt und Gegner besiegt werden. Die Geschichte ist durchweg spannend, auch wenn klar ist, dass dieser Band nur der Einstieg in ein größeres Abenteuer ist. Die Welt von Magnamund zieht einen schnell in einen Bann, so dass sich der Leser heimisch fühlt auch ohne bekannte genre-typische Motive wie Zwerge oder Orks.

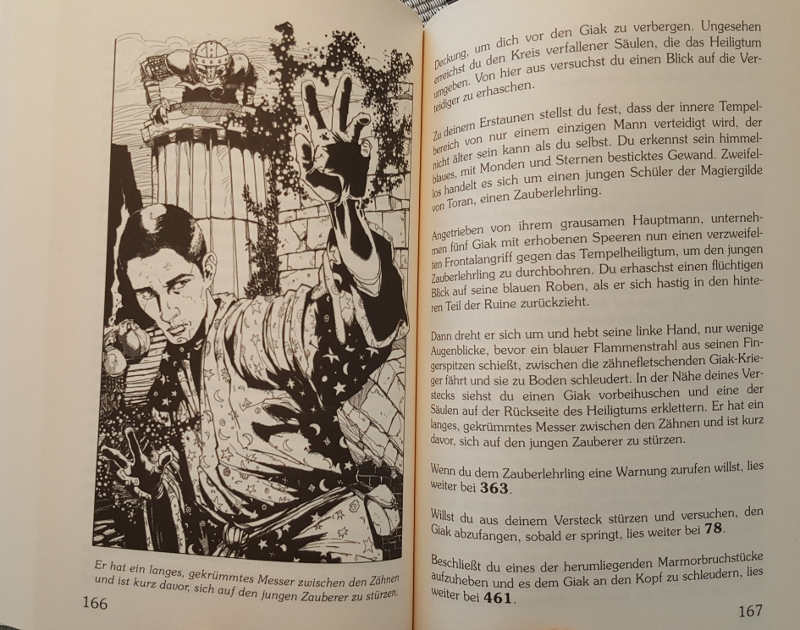

Das Kampfsystem erlaubt schnelle und zum Teil sehr schwere Kämpfe, die schnell verstanden und ausgewürfelt sind. Durch die verschiedenen Fähigkeiten, hat man gelegentliche Vorteil und kann einem sonst verschlossene Pfade und Gefahren erkunden. Zusammen mit der Wahl auf verschiedenen Wegen nach Holmgard zu gelangen, ist der Wiederspielwert hoch. Sollte man dem Zauberer Bandeon nicht begegnet sein, empfehle ich das Abenteuer noch einmal zu spielen. Die Illustrationen von Rich Longmore sind zweckmäßig, wobei einige Momente des Abenteuers toll eingefangen werden. Mit den düsteren und zum Teil unbehaglichen Illustration von Gary Chalk aus der Urfassung können sie dann nicht ganz mithalten. Die Deutsche Übersetzung erlaubt sich den einen oder anderen Patzer, trübt aber das Erlebnis nicht.

Mit Flucht aus dem Dunkel liegt ein gutes Spielbuch vor, dass man jedem Einsteiger aber auch altem Fan empfehlen kann. Leicht zu erlernen, viele Handlungsmöglichkeiten und die Aussicht auf viele weitere Abenteuer.

Buchinnere (Eigenes Werk. Lizenz: CC-BY-SA.)