Latest reviews

How much do you know about the overthrow of the Kingdom of Hawaii, about the Philippine-American War, about America’s efforts to depose José Zelaya in Nicaragua, Jacobo Árbenz in Guatemala, Mohammed Mossadegh in Iran, and Ngo Dinh Diem in South Vietnam? If the answer is “very little”, Stephen Kinzer’s 2006 book Overthrow remains a reasonable introduction to these and other “regime change” efforts.

Kinzer, a journalist and writer who was the New York Times correspondent for Central America in the 1980s, weaves a narrative of some of America’s military and intelligence interventions in other countries from the late 19th century to the early 21st. He connects the political events with the stories of some of the key figures involved, like Henry Cabot Lodge and his grandson, Theodore Roosevelt, and the Dulles brothers—John and Allen, subject of another book by Kinzer.

Throughout his analysis, Kinzer points at the clear commercial interests at the root of foreign policy interventions: taking control of Hawaii at the request of American-born plantation owners, preserving United Fruit’s corporate stranglehold over Guatemala, punishing Iran’s Mossadegh for attempting to end foreign exploitation of the country’s oil reserves.

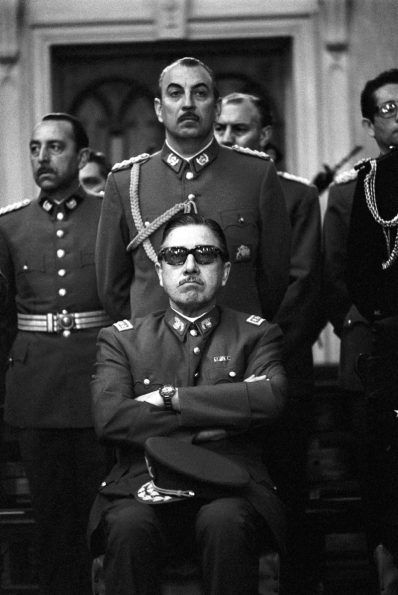

After a directive from Richard Nixon to “make the economy scream” through sabotage, the CIA used the subsequent instability to help install Augusto Pinochet, replacing Chile’s democratically elected leader, Salvador Allende. Pinochet’s regime was responsible for the death of thousands, and for the arrest and torture of tens of thousands. (Credit: Chas Gerretsen. Fair use.)

The typical pattern of each chapter is “storytelling → larger political events → analysis”. As a storyteller, Kinzer is not quite at the level of Erik Larson—there are some slightly jarring repetitions, for example—but the book is certainly engaging.

The book’s value is ultimately limited by its narrow scope, and by its unwillingness to stray too far outside the Overton window of American political discourse. For example, America’s many efforts to influence democratic elections in other countries help to understand why democracy and political independence are often difficult to reconcile for smaller countries.

But these efforts, far more numerous than direct intervention, are largely out of scope, as are many of the other methods America’s military and intelligence apparatus have employed (and continue to employ) to bolster friendly regimes, however brutal, and to undermine perceived unfriendly ones.

When Kinzer imagines “what-ifs” for countries like Guatemala and Nicaragua, he theorizes that America stunted the emergence of independent capitalist democracies. In full cognition of the historical facts, it should not take much daring to speculate whether democracy and capitalism are in fact compatible at all.

The book’s narrative ends with the near-term effects of George W. Bush’s war in Afghanistan and Iraq. Kinzer’s 2006 prognosis for both countries was not optimistic; today, one would have to connect the dots between these interventions, subsequent American and European actions in the region, and the terror, wars and instability that continue to this day.

I recommend Kinzer’s book with the above reservations as a starting point to explore America’s imperialist history. It may also serve as a cautious introduction for readers wary of more radical authors like Chomsky (who eloquently critiqued Kinzer’s New York Times reports from Central America in the 1980s). 3.5 of 5 stars, rounded up because of the importance of the subject and the quality of the writing.

Ancient statues and buildings were frequently painted in vivid colors. The modern image of austere white marble is largely an invention, based on misunderstanding the weathered appearance of ancient works as intentional. That invention became the preferred view of antiquity from the Renaissance to today.

Ancient polychromy is not, however, a recent discovery. After all, statues often still had pigments on them when they were discovered (many still do so today). Historians like Johann Winckelmann (1717-1768) acknowledged that many ancient statues were colored, but claimed that “the whiter the body is, the more beautiful it is.”

The true colors of the ancient world reflect the diversity of the people that inhabited it. They also make the ancient West look a lot more like the ancient East, offering a glimpse at the thread that connects all humanity; sharpening the contrast between the polytheistic, messy culture of ancient Rome and the darkening age that followed it.

Since Winckelmann, historians have rarely embraced, sometimes rejected and mostly ignored the true colors of antiquity. In recent decades, a small number of archaeologists and historians have tried to change that, culminating in an exhibition of painted statues called Gods in Color which first opened 2003 and has been continuously updated since then. The book Gods in Color: Polychromy in the Ancient World is a catalog of the exhibition with some additional essays on the subject.

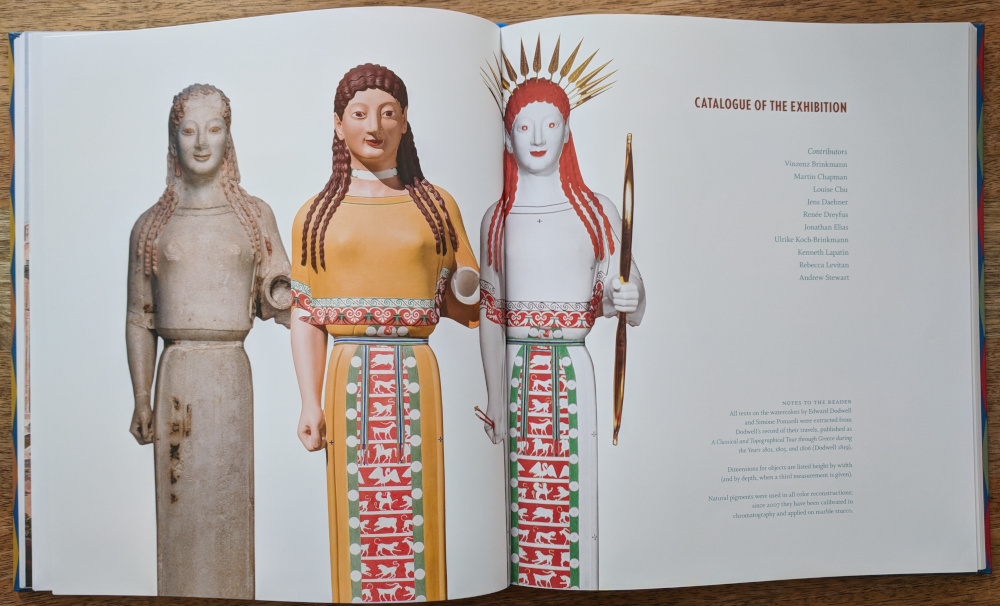

Reconstruction of the Peplos Kore as featured in the book. (Credit: Gods in Color. Fair use.)

The introductory essays are short but interesting, shedding light on the discovery and perception of ancient polychromy, and giving examples of early drawings and reconstructions.

The new reconstructions, however, may offend modern sensibilities. This is less because they’re colorful and more because they just are not very well done. As Margaret Talbot writes in the excellent New Yorker article “The Myth of Whiteness in Classical Sculpture”:

In the nineteen-nineties, [Vincent] Brinkmann and his wife, Ulrike Koch-Brinkmann, who is an art historian and an archeologist, began re-creating Greek and Roman sculptures in plaster, painted with an approximation of their original colors. Palettes were determined by identifying specks of remaining pigment, and by studying “shadows”—minute surface variations that betray the type of paint applied to the stone. The result of this effort was a touring exhibition called “Gods in Color”.

(…)

But [Mark] Abbe, like many scholars I talked to, wasn’t crazy about the reconstructions in “Gods in Color.” He found the hues too flat and opaque, and noted that plaster, which most of the replicas are made from, absorbs paint in a way that marble does not. He was also bothered by the fact that the statues “all look fundamentally the same, whereas styles would have differed enormously.”

All of this is true. Moreover, many of the depicted reconstructions are incomplete, with partially colored eyes or limbs creating a truly garish appearance. Where the original is damaged, so is the replica, with a white broken nose at the center of a flatly painted plaster reconstruction.

The pigments recovered from each original are carefully documented, but the artistic execution of most of the reconstructions is accordingly mechanistic, constrained by evidence that remains between us and the ancient world.

The result is a presentation of antiquity in painted plaster that resembles the uncanny valley of bad computer graphics. The Brinkmanns and their collaborators deserve the world’s credit for forcing us to take a more realistic view of the ancient world in its full color—but a lot of work remains to do so in style.

Monoprice Maker Select V2 is a near direct copy of a Wanhao Duplicator i3. This printer optimizes the i3 design for mass production using steel sections for the frame and electronic housing. Notable for coming nearly assembled and the low price(269.99 as of 11/2018).

Assembly

Involves screwing the steel upright to the x axis and running some cables, quite easy.

Components

The steel frame is quite sturdy, better than Original Prusas on the Z axis. Bed works well at first, but you’ll find the adhesive surface on top wears out rather quickly and entire bed assembly is poorly designed. Spoolholder is basic and too small for spools from Monoprice.

Printing

Tested with Monoprice PLA, printing went well at first with suprisingly good print quality. Over time, printing becomes more frustrating. The bed surface will need to changed frequently if printing regularly. The bed has become less true forcing me to use rafts and only use a 2"x2" square in the middle of the bed to get quality parts. Dimensional accuracy in the X and Y axes seemed to suffer scaling issues where it would undershoot dimensions.

Software/Firmware

I used Cura and Repetier to slice and control the printer. I recall everything working fine once setup. I had to pull printing profiles from the gcode on the sd card that came with the printer. The printer size and connection details had to be filled in to the host software. Acceleration/jerk limits were terrible, the frame would develop z wobble sometimes even though the frame is overbuilt to the point this shouldn’t be an issue.

Tweaks

There are many suggested fixes included for the common bed leveling issue. Locknuts for the thumbscrews, sturdier x axis carrier and replacing the bed with a PEI build surface. Also, a I’ve seen a MOSFET mod recommended as there’s reports the bed heater can overload a connector and possibly start a fire. Reportedly, implementing these fixes will make this a good printer.

Verdict

This is a decent printer for playing with 3D printing at a low price. If you want it to be a reliable machine, you’ll need to tweak many things to get there.

Spool created by Slant 3D to optimize the masterspool idea of a 2 piece reusable spool that accepts spoolless filament refills. The Slant Spool’s main change is switching from a threaded locking mechanism to a 1/4 turn mechanism and it works exactly as advertised. The mechanism change also allows both sides to be identical which simplifies printing and upkeep. The solid portion on the outside of the reel is perfect for the filament id sticker that comes with the refills. Lastly, there’s filament sized holes in the outside of the reel to hold the loose end when you’re not using the filament.

Website for 3D printing files made by members of the RepRap project. Website is clean and usable. The selection is much smaller than thingiverse which limits its usefullness.

In November 2015, Nathan Robinson and Oren Nimni launched a Kickstarter to fund the creation of Current Affairs, a print magazine of “political analysis, satire, and entertainment” promising to “make life joyful again”. The campaign exceeded its goal of $10,000. Three years later, Current Affairs has become of the most reliably interesting and, indeed, enjoyable political publications on the left.

Print editions are issued every two months; each is carefully designed and, in addition to articles on diverse topics, every issue contains the creative works of many contributing artists. While many illustrations simply support a given article, in other cases it’s the illustrations that tell the story—see, for example, the “City of Dreams” illustration and accompanying article.

Recent Current Affairs covers. (Credit: Current Affairs. Fair use.)

Chances are that you’ve come across Current Affairs articles before through some of Nathan Robinson’s in-depth “takedown” articles about prominent American and Canadian political writers — especially those spreading reactionary ideas, e.g., Ben Shapiro, Charles Murray, Sam Harris, Jordan Peterson, Mike Cernovich, and Dinesh D’Souza.

Instead of simply dismissing them outright, Robinson takes these figures to account on the basis of their own words, dissecting the ugly mess of hateful nonsense beneath whatever persona they’ve created for themselves.

Current Affairs is a decidedly leftist publication; it routinely condemns capitalist excess, corporate misconduct, “bipartisan” alliances with murderous regimes, the convenient political amnesia concerning America’s history of horrific military interventions, the dark legacy of racism at the root of deep social and economic inequalities.

While it writes of socialism as a political and economic alternative, the magazine has been equally critical of authoritarian socialism. Robinson’s own essay, “How To Be A Socialist Without Being An Apologist For The Atrocities Of Communist Regimes“, puts it quite plainly:

The dominant “communist” tendencies of the 20th century aimed to liberate people, but they offered no actual ethical limits on what you could do in the name of “liberation.” That doesn’t mean liberation is bad, it means ethics are indispensable and that the Marxist disdain for “moralizing” is scary and ominous.

Current Affairs instead leans towards libertarian socialism, an ideology seeking to balance a high commitment to individual freedom with a concern for the welfare of societies. It speaks of “humanistic” values and holds all ideologies to account for living up to those values.

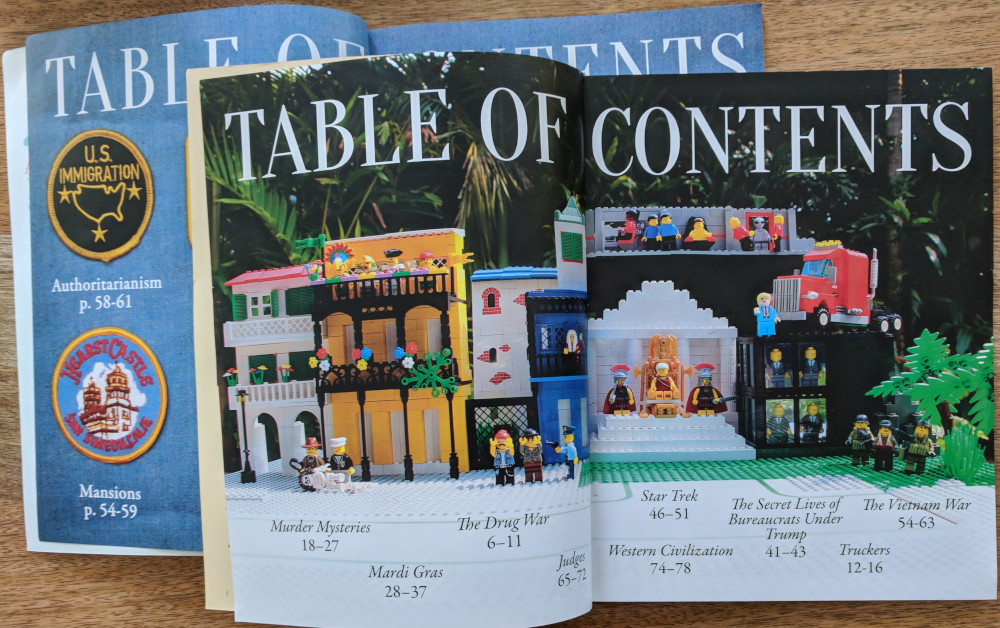

The magazine publishes essays about diverse topics from the changing politics of Star Trek to the Mardi Gras holiday in New Orleans. You’re in for a visual treat the moment you open the table of contents, each of which is an artistic exploration of the topics covered in the current edition.

Current Affairs table of contents examples. (Credit: Current Affairs. Fair use.)

Alongside its playfulness and occasional silliness, the magazine features articles such as a gut-wrenching and unflinching look back at the Vietnam War (“What We Did”) or an insightful report on disillusioned African-American Rust Belt voters (“The Color of Economic Anxiety”).

Recently, the magazine also launched a podcast; as of this writing, it is already generating more than $6,000/month in Patreon support (supporters get access to bonus episodes). The podcast features conversations between the magazine’s contributors on a wide variety of topics, featuring segments like “Lefty Shark-Tank” (tongue-in-cheek criticism of left-wing policy ideas), interviews, answers to listeners, parody ads, and more.

Legally, Current Affairs is not a nonprofit; Nathan Robinson told me by email that the team “debated it and then decided against it as it creates all kinds of logistical headaches”.

However, he emphasized that Current Affairs will never operate as a for-profit company. Over the course of each magazine’s two-month run, all articles are published online without any kind of paywall, and the website and magazine are entirely free of third party ads. Regrettably, articles are under conventional copyright, as opposed to a permissive Creative Commons license.

Article example from the latest issue. (Credit: Current Affairs. Fair use.)

The Verdict

After reading their online edition for a while, I subscribed to Current Affairs earlier this year, and have not regretted it yet. At $60 for 6 issues, you get good value for your money; the magazine is a pleasure to look at, and I generally read it all the way through before the next one arrives.

A few typos usually slip through, and some articles would benefit from more rigor (data, citations) or additional editing. But these are the kinds of problems you would expect from a small, independent magazine.

In many ways, I prefer the Current Affairs model to the heavily grant-funded nonprofit publications I’ve reviewed (e.g., The Marshall Project, ProPublica). It will likely never be able to muster the resources to engage in a similar scale of reporting projects, but its writing is fearless and independent, funded entirely by readers. While its humor can be snarky, underneath it there’s an earnestness that’s disarming and likable. I highly recommend checking it out.

Would you enjoy reading it? Fortunately, that’s easy to find out by browsing the archives of the website. Regardless of its legal status, I’ve also added it to the Twitter feed of quality nonprofit media, which is a convenient way to sample the content of many nonprofit outlets if you happen to use Twitter.

A large repository of mostly openly licensed files for 3D printing. Instructions for printing the objects or why the objects exist can often be spotty. Be aware that this website is owned by Makerbot who is owned by Stratasys. Uploading or remixing a thing requires a Makerbot account.

Intro

I bought a spool in August since it’s $25 per KG and goes down with the volume you buy to $21 for 4 at a time. Matterhackers also has free shipping to anywhere in the US making this a good deal for PETG. The spool arrived in a vacuum sealed bag with desiccant inside. The first spool printed great with default Prusa PETG settings. Bed ahesion on a PEI printbed is very good if bed is clean. I ordered 2 more 1kg spools in September and have been having constant issues with material accumlating on the nozzle and then detaching leaving blobs and voids on parts. It’s unclear if the issue is with my printer or the material at this point. It’s unlikely I’ll be able to fully troubleshoot the problem in the near future since Matterhackers is out of stock.

Quality

Diameter measured an averaged of 1.73mm diameter taking multiple measurements with calipers on two different spools. This puts it well within the advertised spec of 1.75 ±0.07mm. No visible impurities were seen. Filament fed nicely off spool.

Print Settings

Prusa Generic PETG Settings 230C Extruder/85C Bed 1st layer, 240C/90C Bed after 1st layer

Matterhackers recommended print settings 230-255C Extruder/55-77C Bed

Availability

Matterhackers seems to have issues keeping their build series PETG in stock. This color has been out of stock for a couple of weeks and is estimated to be out of stock for another month.

Verdict

The pricing is good when buying several at a time, product arrives in a timely manner and product quality may be good (assuming the problem is with my printer). The availibilty issues combined with questions on quality leaves me looking for another source for PETG.

In 1971, Daniel Ellsberg leaked the Pentagon Papers to 19 newspapers. Comprising 7,000 pages, they are an internal history of the Vietnam War compiled by the US government. By doing so, Ellsberg made himself a target of the Nixon administration. The first operation of Nixon’s infamous “White House Plumbers” was the burglary of the offices of Ellsberg’s psychiatrist in order to find materials that could be used to discredit him. Later, members of the group would break into the Watergate hotel, bringing down Nixon’s presidency.

Secrets, first published in 2002, is Ellsberg’s memoir. It focuses on his work for the RAND Corporation and the Pentagon, including the time Ellsberg spent in South Vietnam, and the influences on his thinking that ultimately moved him to become a whistleblower.

A Harvard-educated intellectual, Ellsberg was quickly drawn into the upper echelon of US policymaking. In the early part of his memoir, he describes how, at the Pentagon, secrecy was used not just to conceal information from the public, but also to wage turf wars between departments, with new classifications being invented just to prevent rivals from seeing a certain memo or document.

He is not shy to admit the seductive and addictive nature of access to secrets, and how it breeds contempt from political insiders for the outside world. The public, after all, never knows the true reasons why a political decision was made, so how could the judgment of any member of the public be trusted? Lying to the public in official statements is so common that when lies are used to justify war — as was the case after the Gulf of Tonkin incident — it hardly seems notable to those on the inside.

From skeptic to cynic, from cynic to activist

Yet, Ellsberg was not a critic of this system at the time; he was a willing participant. When he was offered his role at the Pentagon with a specific focus on Vietnam policy, he was at first reluctant not because he questioned US motives in the war — as a Cold Warrior, he shared a desire to limit the spread of communist influence — but because he was skeptical that the war was winnable.

During his two years in South Vietnam, Ellsberg’s skepticism turned into cynicism, as he observed how, with all the unspeakable brutality of the war, there was no strategy or tactic that promised real gains against North Vietnam, short of the total destruction of the country. Moreover, forces on the ground even fabricated entire operations to pretend that “pacification” was around the corner at any moment.

Upon his return to the US, Ellsberg struggled to understand how successive presidencies could push forward a war that was going nowhere and costing hundreds of thousands of lives. Had these presidents simply been victims of their own propaganda? To find out, he participated in the creation of the report known as the Pentagon Papers. And it was his inside knowledge of the report, combined with his exposure to the peace movement, that ultimately caused him to become a whistleblower.

The Pentagon Papers showed that, far from cluelessly bumbling into war, the United States had recklessly escalated a war of aggression against a country that, to begin with, had sought independence from a colonial power, much as America had once done. But here, America had chosen the side of the colonizers.

Presidents Eisenhower, Kennedy and Johnson had willingly signed off on escalation after escalation, even as advisers were telling them that far greater efforts were needed to “win” the war. And it was the Nixon administration that would take the war to levels that can only be described as state terrorism, as Nixon himself promised privately: “We are not going to let this country be defeated by this little shit-ass country.” And he made it clear to Henry Kissinger: “You’re so goddamned concerned about the civilians—and I don’t give a damn. I don’t care.”

While Ellsberg would only learn about these statements when the Nixon White House tapes became public, he did know from insiders that Nixon was lying about pursuing peace in Vietnam, and that he was instead prepared to again escalate the war’s brutality in hopes of forcing North Vietnam to “negotiate” with the United States.

This threat of escalation motivated Ellsberg to try various venues to get the Pentagon Papers out, ultimately releasing them to many newspapers as a dramatic man-hunt against him got underway. The Pentagon Papers didn’t cover the Nixon period, and they mostly reflected poorly on previous Democratic administrations. Nevertheless, Ellsberg felt that making visible how administration after administration had made the same mistakes in Vietnam — and lied about it to the public — would at least help hold Nixon to account.

Nixon, for his part, privately welcomed the leak. It was only when he feared that Ellsberg had more material pertinent to his administration that he fully escalated an effort to silence Ellsberg. Aside from the break-in at his psychiatrist’s office, the Plumbers planned a physical attack against Ellsberg at a rally. In his own autobiography, Gordon Liddy confessed that the Plumbers even considered lacing Ellsberg’s soup with LSD before a public speech, to make him appear like a nutjob.

This criminal campaign failed, and as it was exposed, so did the indictment against Daniel Ellsberg. To this day, Ellsberg remains an outspoken activist against war and secrecy, and in defense of whistleblowers like himself.

The verdict

Secrets is an essential account of how secrecy can turn a republic into an empire, at least where foreign policy and “national security” are concerned. As a book about the Vietnam War, it cannot begin to scratch the surface of the horrors inflicted upon the Vietnamese. But to understand how we can prevent history from repeating itself — how we can undermine the secrecy machine by supporting whistleblowers, and how we must demand transparency whenever our government kills on our behalf — Secrets is as timely and necessary as ever.

Disclosure: I work for Freedom of the Press Foundation, where Ellsberg is a Board member.

As of this writing, James C. Scott is 81 years old. Best known for Seeing Like a State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed (reviews), he is an accomplished scholar of non-state societies. Near the end of his career, Scott is not pulling any punches. Against the Grain seeks to dismantle the standard civilizational narrative — that early state-based agricultural societies were part of a linear progression towards civilization as we understand it today.

Scott demonstrates that the hunter-gatherer lifestyle that preceded sedentary agriculture was egalitarian, relatively peaceful, and allowed for significant leisure time, and that early human cultures combined a variety of approaches to survive. Beyond hunting and gathering, these included shifting agriculture, pastoralism (raising livestock and moving the herd in search of new pastures), and even sedentary agriculture, well before the emergence of states.

Our ancestors were opportunistic and looked for the quickest way to make a living. Agriculture wasn’t necessarily a response to population pressure — depending on the environment, it just offered a more reliable return than hunting and gathering.

In Scott’s narrative, the creation of what he calls “late-Neolithic multi-species resettlement camps” — settlements where humans, livestock, other domesticated animals like dogs, and domesticated plants lived together for extended periods of time — caused never before seen levels of drudgery and misery. The high population concentration led to disease and crop failures, and agricultural cultivation created tedium and reduced cultural complexity.

But it also created opportunities for those who accumulated power to attempt to preserve it. The settlements could be strengthened by abducting and enslaving nomads or members of other communities. By standardizing on cereal grains — “visible, divisible, assessable, storable, transportable, and ‘rationable’” — early states were able to sustain their bureaucracies (and increase elite wealth) through taxation.

A polemic against civilization

War and slavery were not inventions of the state, Scott acknowledges, but it is only through the concentrated power of early states that they could they be brought to a previously unseen scale. When state societies collapsed, many of the enslaved or coerced members (if they survived—a big “if” Scott glosses over a bit too readily) were better off. And state collapse occurred frequently, due to disease, war, starvation, rebellion, and other causes.

Meanwhile, the “barbarians” who did not join state-based societies (and who could not easily be captured because of where they lived) became more sophisticated, extracting tribute from the state — but also selling each other out to serve as mercenaries for hire.

Where Scott’s writing turns into polemic is when he dismisses the idea of “dark ages” (such as the Greek Dark Age or, though he barely writes about it, the period following the collapse of the Roman Empire). The fact that we don’t find monumental buildings, wall paintings, or a strong written tradition, he reminds us, doesn’t mean nothing of interest happened — after all (a point Scott repeats), Homer’s great epic was composed during a “dark age” and transmitted orally.

Scott persuasively marshals the evidence that concentration caused many new hardships, and led to societies which were frequently (if not always) deeply unjust. But he does not attempt to examine the arguments against dispersal, or for large numbers of humans living with each other in close proximity, sharing ideas and beliefs at a pace previously unimagined.

He dismisses “elite displays” such as monuments and temples, but does not write about roads, aqueducts, libraries, poverty relief such as the Cura Annonae, or any legitimate effort to better the life of a community’s members, if such life was organized partially through a state.

Indeed, the word “science” does not appear in the book’s index. Human progression that is the result of better understanding our world and applying that knowledge is too readily dismissed in an effort to keep the book true to its title.

Here, Scott’s book — so critical of ideological views of “civilization” — is itself ideologically committed to rejecting an evidence-based view. “But what of the slaves?” one can imagine Scott saying. “But what of the elites, enriching themselves?” Yes, but what of Euclid, Democritus, Ovid? What of the Library of Alexandria, or the Antikythera mechanism, or the art of Pompeii? What of the religious extremism that followed Rome’s collapse, and probably followed earlier collapses as well?

The verdict

Scott uses language not to obfuscate, but occasionally in ways I would describe as performative. Against the Grain makes frequent use of technical terms from agriculture and anthropology; the writing is dry (though suffused with a dark academic humor) and sometimes repetitive. What keeps the book interesting is its challenge to orthodoxies and its willingness to put things plainly when required, e.g., when writing about slavery.

Against the Grain does re-cast our understanding of history. Scott is correct to critique those who want to see linear progression in human history; a rise from savagery. Deep history that looks at the distant past of our species is crucial to get a clear picture of how we became who we are. Our hunter-gatherer ancestors were far from stupid, and their minds were far from simplistic compared to our own, nor were their lives especially brutal or difficult.

History cannot be understood without examining the accumulation of power and resources, all too often including slaves and other coerced labor. If we want to build morally just societies, we must understand how this accumulation of power is at odds with moral progress, even as it has often enabled scientific or technological progress.

But here ends the usefulness of Scott’s book. The fact that his work celebrates the dispersed life beyond the reach of the state is perhaps precisely why his colleagues can celebrate him as an anarchist academic. His writing poses no threat to real systems of power, because it offers no alternative. It is an important read, but only as a starting point for developing a more nuanced understanding of the human story, correcting misconceptions in the common narrative still taught in schools. In the final analysis, Scott is a rebel without a cause.