Latest reviews

Sometimes I pick up indie games that look just weird enough to be interesting. Alien Function is definitely such a game. It is part of a series featuring the same cast of characters, but it works as a standalone story.

You play a guy named Typhil, who works as an agricultural technician on a starship that seems to have no aim or purpose other than to maximize its production of rutabagas.

The first half of the game could be described as a “daily grind simulator”, in which you are assigned various technical tasks related to rutabaga production: optimize fertilizer output, manage pest control, and so on. You do this by piecing together clues on a virtual desktop that looks kind of like Windows 95.

Through limited interactions with your colleagues on the starship (who are dressed like they escaped from a fantasy RPG) you become aware of a series of crew member disappearances. Eventually, a colleague teaches you hacking skills, and you start to snoop around in the ship’s private data stores…

You have to have a certain amount of respect for a game that puts a unicorn in the holding cell of a starship. (Credit: Stand Off Software. Fair use.)

The gameplay is a combination of 3D point-and-click with puzzle elements. There is no hint system, and there is only autosave, but I never got into a dead end where I could no longer progress. I finished the game without a walkthrough in about 4 hours—indeed, its’s so obscure that no walkthrough appears to exist as of this writing.

Astonishingly, Alien Function is fully voice-acted. While nobody is going to win any awards for it, I never found it grating (well, almost never—one character sounds constantly annoyed, but I think she is supposed to).

The story doesn’t hold any dramatic surprises, and the mid-2000s quality 3D graphics (pieced together from various assets), combined with some drawn out puzzles, make it difficult to truly recommend the game. As an indie passion project that delivers 4-5 hours of surreal playtime, it’s still an achievement. If you do pick it up, make sure to start with the tutorial, which is both funny and important to understand the game’s controls.

Kelvin and the Infamous Machine (2016) is an indie point-and-click adventure in the tradition of games like Day of the Tentacle (1993) and films like Bill & Ted’s Excellent Adventure (1989). It was developed by Blyts, a small Argentinian studio that managed to raise just under $30K in a Kickstarter to fund its work.

The game follows a classic premise: 1) scientist invents time machine; 2) scientific community ridicules scientist; 3) mad scientist goes back in time to claim credit for the world’s greatest scientific and creative achievements. Kelvin and Lise, the mad scientist’s research assistants, try to stop him and to set things right(-ish).

The game’s cartoon graphics are not overly detailed but still appealing. A rich cast of characters keeps things interesting. (Credit: Blyts. Fair use.)

A Tales As Old As Time

You exclusively play as Kelvin, a clueless goofball willing to try almost anything. That makes him a great protagonist for a point-and-click adventure where much of the gameplay consists of picking up every random item you see in hopes that it will be useful to solve some puzzle later on.

Our adversary, Professor Lupin, has messed with Ludwig van Beethoven, Leonardo da Vinci, and Isaac Newton—preventing them from completing their work, while claiming all credit for himself. Kelvin, guided remotely by Lise, visits their respective time periods to restore some semblance of sanity.

The world is filled with wacky characters—a tea merchant selling a disgusting brew made with a contraption of military origin; an utterly incompetent incarnation of Robin Hood; a gravedigger enamored with pictures of cute animals.

Short but Well-Rounded

This is a comedy game that relies heavily on pop culture references, from Harry Potter to Doctor Who. It’s not quite as consistently funny as comedy adventure hits like The Darkside Detective, but it definitely has its moments.

You’re likely to finish Kelvin in 4-5 hours. The mostly inventory-based puzzles can get a bit tedious, but thanks to good game design, you’re unlikely to get stuck anywhere for very long. The game is fully and competently voice-acted; the overall sound design could have used some polish (music does not always play when you may expect it to). The user interface is as simple as it gets, with one-click interactions and fully automatic saves.

3.5 stars, rounded up for the little details that show that it’s a work of passion—such as optional, unlockable scenes that reward extra exploration. Especially recommended for younger audiences.

There’s a good chance that you own multiple devices that give you access to an almost limitless library of games. But there was a time when video game arcades were the place to go to exchange coin after coin for minutes or hours of entertainment—alone or in the company of your friends.

That’s the past that 198x evokes, promising “a coming-of-age story told through multiple games and genres”. Our protagonist, “Kid”, is an alienated suburban teen who discovers a local video game arcade as a means of escape.

The story is minimalist and mostly told through large, beautiful pixel art scenes. Kid is also the game’s narrator. Their melodramatic monologue is at odds with Kid’s privileged and not particularly eventful adolescence. The story ends on a flat note, promising a sequel which may or may not come.

At the core of 198x are five video game vignettes: a beat ‘em up, a space shooter, a racing game, a hack-and-slash platformer, and a dungeon crawler.

Shadowplay is the most well-rounded of the minigames, with wonderful art and a genuinely creepy boss that chases you in the final stage. (Credit: Hi-Bit Studios. Fair use.)

These are not fully fleshed out games, and they fade out after a few stages. They do successfully evoke the 16-bit gaming era, with Out of the Void (the space shooter) and Shadowplay (the platformer) feeling the most developed.

Most players will be done with 198x after 1-2 hours. Depending on your tolerance for teenage angst, you may find the storytelling portion more annoying than atmospheric; either way, the pixel art is undeniably gorgeous throughout the game.

I would give the game overall 3.5 stars, rounded down because of the underwhelming story. If you like retro games and pixel art, I would recommend checking it out at a discounted price or in a bundle.

Metroid: Other M is the 2010 main entry into the long-running Metroid series that hadn’t seen a major release for almost a decade at that point with Metroid Fusion. The series at large had already seen a return to home consoles with the Metroid Prime spin-offs, but this game brought the main series back to them as well. With this return Team Ninja and Nintendo attempted to give this series a new coating: getting the main series to 3D, shifting the gameplay focus to combat, and extending the Metroid universe with a huge story.

Similarities/Differences

There is a lot of overlap with previous Metroid games in Other M, despite these huge ambitions.

Structurally the game borrows heavily from Metroid Fusion, taking place in a huge spaceship with one main sector that branches off into several others, each with a different theme. And also the story takes quite a bit out of Fusion’s book: it focuses on the Galactic Federation and its secret bioweapons research—just much bigger in scope this time.

The transition to 3D had already happened successfully for the series with the aforementioned Metroid Prime by Retro Studios. And certainly, a lot of lessons learned about how to transform the exploration of environments from 2D to 3D were applied here. But unlike Metroid Prime, Other M uses the third-person perspective, instead of first-person.

Story

The main difference between this game and the rest of the series is the storytelling. Up until this point the series had mostly relied on telling its story through the environment and events that are experienced directly in the gameplay space. This basic approach had already been extended by Fusion with a periodically delivered monologue, either directed at the protagonist, Samus Aran, or monologue of her own—directed inwards. Other M keeps all of this and erects a framework of a grand, traditionally told story around the entire game. Samus receives a backstory, explicit characterisation, and a cast of characters to interact with. On top of that, the game is fully voice acted. And all of this is supported by pre-rendered cutscenes by the animation studio D-Rocktes, which look spectacular, especially by Wii standards.

The game is set directly after the events of Super Metroid. Samus returns from her mission in that game, in which she successfully obliterated the planet of the Space Pirates. The baby Metroid that she set out to rescue on the mission, however, sacrificed itself in the final battle to rescue her.

Other M sets off when Samus receives a distress call which leads her to a seemingly abandoned and gigantic spaceship. And there she coincidentally bumps into a Galactic Federation squad under the leadership of her former military superior Adam Malkovich. She joins the group under Malkovich’s command and they begin investigating the place together. Soon it becomes clear that the ship houses the Galactic Federation’s secret bioweapons research project and that the place might house some other secrets too.

The story builds up Samus’ character and paints a pretty harrowing picture. The loss of the baby Metroid that saw her like a mother has affected her greatly and now, meeting people from her old life in the Galactic Federation army, opens up many wounds from the past. The game communicates her bad mental state by giving her a cold, detached and monotone voice, especially for internal monologues.

Throughout the game, you dive deeper into her damage with previous missions of hers and specifically her relationship to Adam, whom she sees as a father. This is also why she joins the group so readily under Adam’s command: she wants to make amends for the mistakes that lead to her leaving the military. She wants to prove her loyalty to him.

Broadly, the game has a theme of loss of control. Not only does Samus, who generally works alone, surrender authority to Adam, but further, many important plot points in the story do not get resolved by her. She isn’t the one in control, even though she is the protagonist of the game.

Moreover, by casting the Galactic Federation in the role of the villain, Samus doesn’t have much room to play the hero. After all, those are the people on whose behalf she just carried out her last mission.

The good-evil reversal with the Galactic Federation doesn’t sound all that interesting on the surface—that’s what Fusion already did—but combining it with Samus’ involvement and turning it into a story of overcoming trauma is a lot more compelling already. It goes further though: not only does nothing fundamentally change about the evil parts of the Galactic Federation, its bioweapons experiments continue in Metroid Fusion, which chronologically follows Other M. Adam Malkovich is portrayed as the only counterweight, as he explicitly opposed the bioweapons research but failed in preventing it from happening.

It’s a display of cynicism about the ability of large political constructs being able to rid themselves of their corrupt elements. The parallels with the public debate in Japan about raising a standing army once again, which is pursued by an ultra-nationalist elite, but majorly opposed by the general public, are striking. And beyond the contemporary political messaging, it also touches on the uneasy realities of being complicit in such an organisation, like Samus is. She continues to work with the GF, only to realise that nothing changed and finally breaks with them in Fusion. This allows her to finally step into Adam’s footsteps in defying the Federation.

Another thing I appreciate about the story is how it humanises Samus’ character in a way the series didn’t up until that point. Fusion set some of the groundwork for this, but here it comes to full fruition.

Humanising a woman that always runs around in a metal suit isn’t very easy, but here it’s made possible by having the story take up a great portion of the game. Not only is Samus given a voice and a face, but also issues and motivations of her own. She appears much more human as a result of her portrayal as a battle-scarred warrior. To keep working her taxing job as a bounty hunter, she had to build up several layers of mental protection. The metal suit she wears doubles as a visual metaphor for this.

The story explores Samus’ traumatic past and her reaction to being confronted with it. Thus overcoming trauma is a huge part of the story. And that is perfectly fine. What is not fine, however, is how this is communicated on screen.

There are several scenes where Samus is confronted with her past and experiences a traumatic response where she loses control over her suit. As a result, her underlying body in a skin-tight suit is laid bare (“Zero Suit”, as the series calls it). This makes the revealing of her feminine physique double as a visual metaphor for her weakness in these moments, which is incredibly sexist. Now, is it more sexist than previous entries in the series “rewarding” you with a sexy pin-up of Zero Suit Samus when finishing the game quickly enough? Hardly. What makes it especially disappointing here, however, is that the game has shown very clear awareness of the fact that previous entries in the series simply reduced her character to a suit and attempts to actively fix the problem. At least the pin-up “reward” is gone in this game, I guess.

This focus on character and story is a sharp turn for this series. While alienating to some, I find it to be the most compelling aspect of Other M. The few sloppy or outright objectionable elements get overshadowed by the good aspects. And as I laid out above, this goes much further than just character and story. While Metroid Fusion didn’t need any of the elaborations of this game, I appreciate the reinterpreted perspective it puts forward.

Gameplay

Between the story beads are longer sections of uninterrupted gameplay. The traditional Metroid gameplay of exploration with combat and the occasional boss fight has been transformed to the third dimension. However, Other M puts the accents on combat, as opposed to exploration, as has usually been the case.

The game uses an unusual control scheme for the Wii. You hold the Wii Remote vertically and control general movement with the D-Pad and the 1 and 2 buttons. The game features a first-person mode, undoubtedly inspired by the Prime series, that you switch to by aiming the Remote at the Wii’s IR sensor. Initially, this can be a bit awkward, but if you are set up properly, you get used to it quite fast.

As is tradition with Metroid, Samus loses her abilities and they have to be reacquired throughout the game. The justification, this time around, is that Adam puts tight restrictions on Samus’ abilities and only authorizes them in appropriate situations. This makes sense from a story perspective and nicely characterizes Samus’ and Adam’s relationship, but leads to situations that disrupt the gameplay in unfortunate ways.

A situation that occurs quite often during the game is that you are put into a situation where you can’t progress due to the lack of a certain ability, and you have to wait until Adam interrupts and gives the okay on that ability. It is later revealed that Adam was testing her commitment to his command and as a result put her into quite a few dangerous situations, which, again, makes for great characterisation, but makes for annoying bits of gameplay. These situations aren’t all that numerous, but since this is about one of the signature elements of a Metroid game, it sticks out.

Another thing the game borrows from Fusion are the light horror elements. There are multiple sections of the game, that in their attempt to build tension, put Samus into a slow walking state with the camera following her over the shoulder. One of these sections is quite extensive. The first time through this works somewhat decently, but on repeated playthroughs, it just disrupts the pacing of the gameplay. This element of the game feels heavily under-baked. Not only did Fusion manage these tension building sections without taking control away from the character like that, but in the case of Other M, they feel much less integral to the experience. They just seem to exist to support the dark atmosphere of the game, and because Fusion had them, which is not enough of a justification to have them have this disrupting of an impact on the game.

Combat

Combat is the main attraction gameplay-wise. Previous games had combat more as an additional component to movement, which took the primary role in gameplay. The only exception to this were bosses, where the combat mostly took over. But due to the greater focus on movement that came at a cost: they were never quite as satisfying as they could have been, at best, or actively frustrating at worst.

This focus on combat and the new 3D space in which it takes place makes for quite a few new additions to the core gameplay. Let’s go over them one by one.

The biggest addition to the combat is that by pressing the correct button in time, Samus jumps to the side, dodging the incoming attack. This makes avoiding attacks quite easy. To compensate for that, attacks from enemies hit harder this time around. And further, certain enemies punish you for overusing the mechanic by pre-emptively attacking the spaces you would dodge to if used multiple times in quick succession.

Another big addition is combat finishers. When an enemy is sufficiently hurt, they enter a vulnerable state, where if they approached from the correct position, Samus attacks the enemy in a scripted event allowing for you to charge your shot and deliver the final blow. During some boss fights, such scripted events also occur without you finishing off the enemy immediately. The combat finishers look absolutely sick. You will not grow tired of them.

There is one problem with this mechanic though. Sometimes, especially during the beginning, the game does not provide sufficient visual indicators when the enemy enters its vulnerable state, allowing for a combat finisher. It makes for a few frustrating moments of just jumping around, trying to get on the head of an enemy, while they get their counter-attack ready.

Yet another change is that you can replenish both missiles and health while actively being engaged in combat. Missiles can be replenished freely, and health can be replenished when you’ve depleted health to a critical degree, allowing you to replenish it to a certain threshold. While replenishing you cannot act otherwise with Samus. For the most part, this doesn’t change the gameplay that much from previous instalments, but if you are out of missiles or health, you can try getting back into the fight in a last-ditch attempt.

All of these things make combat somewhat easier than it was for previous games in the series, but I don’t mind that, because what it primarily does with its focus on combat is to make it a smoother experience. A lot of the challenge in previous instalments came from the uneasy combination of combat and platforming during boss fights, while doing neither particularly well during those moments. So I welcome these changes greatly.

Switching perspectives between third-person perspective and first-person perspective is of great importance during combat. Missiles (esp. when later upgrades are unlocked) do more damage and can only be fired from the FP view. This creates a meaningful differentiation between Samus’ beam and her missiles. The beam is your base damage dealer and missiles are reserved for specific moments during the fight. This can either be a phase where the enemy is only vulnerable to missiles, or the game giving you sufficient time to switch into FP view to deal extra high amounts of damage with a missile.

The switching between TP and FP view during combat might sound clunky, but if your sensor bar is set up appropriately, it works perfectly fine. The game compensates quite well for the short amount of inaction that is the result of changing the orientation of the Wii remote.

Additionally, the separation between missiles and beam gives more significance to the charge beam. It is now the highest damage dealer while you are still being able to walk around.

Visually the charge beam makes for a fantastic looking firework, especially with beam upgrades. The game also features a new collectable upgrade called the “Charge Accel”, which does what its name says. This makes for a nice additional collectable in a game where the use of missiles has been de-emphasised. The faster charge is subtle but increasingly noticeable, which nicely contributes to Samus feeling increasingly more powerful as you progress.

Due to the focus on combat, the game provides a lot more mandatory fights than it has been usual for the series up until this point. A lot of the fights take place in small and locked arenas. Most of these fights are essentially mini-bosses. Having enemies be more on par with Samus makes sense with the smoothed out combat mechanics, but a lot of these mini-bosses feature annoying phases of temporary invulnerability, where the only thing that you can do is dodge. All of these enemies have quick kills that allow you to dispose of them in seconds, but that is nothing that would be accessible to a casual player who otherwise benefits most from the improved combat.

Despite that, the enemy design in this game is great, especially for new enemy types.

Movement

Movement, which so far has been the core gameplay element of Metroid, definitely takes on a secondary role in this game. However, the game does try to evoke the traditional game feel in a lot of ways. Since movement is done with the D-Pad, the camera takes on the important role of providing for a smooth navigation experience through the complex 3D space of Other M. In a lot of places it will guide you along a linear path, so that you only ever need to press one direction on the pad to move forward. The clearest example of this in the game are spiral structures, which the camera just smoothly follows. This minimalism regarding input does instil a hint of classic 2D Metroid. Although, some big rooms that require a lot of 3D navigation exist as well.

And beyond that, the game falls back onto established 2D Metroid tropes, such as rooms serving as small navigational puzzles, and breezing through an entire room by Shinesparing.

Shinesparking in this game looks and feels better than ever. The mechanic has been considerably simplified, which means, that while requiring significantly less skill to use successfully, now this great mechanic can be properly experienced by many more.

If you are looking for a more traditional and movement-focused experience, the post-game of Other M might sound more appealing. With the story being effectively over and being fully upgraded, you can move through the spaceship undisturbed. Now you can focus your attention on collecting upgrades and even exploring previously unseen smaller areas. While that’s a nice gesture towards long-standing fans, it felt more like indecisiveness to me—a bit like an excuse for taking the series in parts into such a radically different direction. I would have appreciated it more if the game embraced its different direction more clearly. The indecisiveness gave us a game split into two parts, where those looking for a different experience are teased for hours until, after completion, the promise of such an experience is tried to be delivered, but due to the core mechanics being focused on combat so much in part one, it never can fully deliver.

Part two isn’t bad but comparatively underperforms. It lays bare some of the clear flaws with the movement in this game. In part one they didn’t stick out as much, since the movement wasn’t the focus.

One of Samus’ powers that has always been very important for movement in the series, but has been changed significantly this time is the Space Jump. Whereas previously it allowed you to ascend infinitely high, as long as you pressed the jump button in the right rhythm, in Other M, it serves more the role of keeping height and passing large rifts in rooms. This means that now if you miss the rhythm, you will probably fall down all the way, with no ability to recover, like you previously did. Having to start over from even simple screw-ups like that becomes frustrating easily.

Another problem is that the 3D depth of the game can be deceiving and a hindrance to your platforming. Other M trains you extensively to trust the camera. But when the camera doesn’t follow you how you would expect it to, the movement flow is interrupted. For example, some platforming instances require you to move diagonally, when it doesn’t look like you would have to move that way. Especially so when the camera up until that point had taught you that just pressing one of the four directions of the D-Pad is fine, even for complex level geometry.

And speaking of level geometry: sometimes it is a bit overprotective at trying to keep you on the platform you are on. This is especially true for earlier sections of the game. Arguably this is good in the first hour of the game when new players still get used to the controls. At that point, you just want to move in one direction anyway. But once you arrive in the post-game it makes for quite the annoyance.

Conclusion

To conclude, Metroid: Other M takes this well-established series into multiple new directions. A lot of this I appreciate greatly. It breezes in fresh air for a series that had fallen somewhat stale in its formula. The new direction has a few issues, but the game seems more haunted by the shadow it is stepping into.

Overall I found this game to be very compelling. I’m saddened quite a bit by the fact that we won’t be seeing the same iterative refinement of the experience this game puts forward, as it was the case for the rest of the series, due to poor sales and fandom reception.

7/10

Mitten in der Stadt, fußläufig zum Hauptbahnhof und zum Stadthafen liegt das Grand Focus Hotel in Stettin. Ich stelle mir unter einem Grand Hotel etwa anderes vor aber dieses Hotel bietet schon sehr guten Service und Ausstattung. An der Rezeption kann in mehreren Sprachen miteinander geredet werden und wie selbstverständlich werden auch exotischere Kreditkarten akzeptiert.

Blick ins Zimmer im Grand Focus Hotel Szczecin (Eigenes Werk. Lizenz: CC-BY-SA.)

Mein Zimmer bot alle Annehmlichkeiten, die ich an ein Hotel dieser Klasse stelle. Mehrere Beleuchtungsmöglichkeiten, die auch vielfach kombiniert werden können. Wasser auf dem Zimmer und Satelliten-TV sind auch dabei. Hochwertige Hygieneartikel im Bad runden das gute Bild positiv ab.

Frühstück im Grand Focus Hotel Szczecin (Ausgewogen sieht anders aus ;-) ) (Eigenes Werk. Lizenz: CC-BY-SA.)

Das Frühstück lässt ebenfalls keine Wünsche offen. Bedingt durch die herrschende Pandemie waren einige Formalitäten (Prüfung des Impfzertifikats) zu klären und dann konnte es los gehen. Die Teller wurden einem nach Wunsch vom Servicepersonal belegt. Von Kuchen über Obstsalat bis hin zum “English breakfast” ist alles dabei.

Für eine oder mehrere Übernachtungen in Stettin ist dieses Hotel sehr zu empfehlen und der schwächelnde Złoty sorgt für günstige Übernachtungen.

Anchuria is the original banana republic. Literally: both the country and the term were invented by O. Henry for Cabbages and Kings, a 1904 collection of interlinked short stories inspired by the author’s stay in Honduras. It is also the setting of Sunset, a 2015 narrative adventure game developed by Tale of Tales—and the game that caused the small studio to give up on making games altogether.

In Sunset, it’s 1972, and you are Angela Burnes, a young, idealistic African-American engineering graduate working as a housekeeper in Anchuria. Your client is Gabriel Ortega, a wealthy man who has recently moved into a new apartment in Anchuria’s capital, San Bavón.

Life in Anchuria

Day in and day out, you perform mundane tasks in Ortega’s large and luxurious penthouse apartment. Over time, you learn about Ortega’s connection to President Miraflores (another name from the 1904 book). The game also reveals more about why Angela and her brother are in Anchuria in the first place.

The daily tasks expand from household chores to the examination of documents and photographs. While you don’t ever interact with Ortega in person, you can exchange notes with him. How you perform your household tasks (efficiently, with a touch of intimacy, or not at all) also affects your relationship with Ortega.

Every day, you can look outside the apartment’s large windows, where the larger political story of Anchuria unfolds. An LED news banner on a building speaks of terrorist attacks. You hear gunfire and see smoke. And some of the fighting is taking place dangerously close to the apartment.

Through the apartment’s windows, you can see the cityscape of Anchuria’s capital. Here, a larger political story unfolds throughout the game. (Credit: Tale of Tales. Fair use.)

Apartment Quest

It’s a fascinating premise that’s a welcome departure from forest elves and space stations. During a few moments in the game, I really was drawn in by the intrigue and by the drama in the streets. Unfortunately, the game’s only mechanic—perform tasks in a large apartment every day—becomes as tedious as it sounds very quickly.

It doesn’t help that some of the tasks are ambiguous (“collect papers”), so you have to do the 3D equivalent of pixel hunting throughout the apartment to complete them (fortunately, you can skip them as well, which I had to do a few times).

There are technical issues, too. The graphics are just serviceable by 2015 standards, yet the game’s engine performs poorly. The gamepad controls occasionally lose their mind and have to be reset. And in the Linux version at least, the game skipped right over the ending for me—I had to watch it on YouTube.

It’s a shame—there’s a lot of worldbuilding here, decent voice acting, and some good writing. There are lots of little touches that reveal the labor of love behind the game, such as many vinyl records you can pick up and play, including “Anchurian” music. One can hope that the game will at least inspire other indie developers.

The Verdict

Sunset could have worked well as a smaller game. By spreading its repetitive gameplay over 4-6 hours, it will overstay the welcome of all but the most patient players. To add insult to injury, in the late game, Ortega packs up a bunch of his stuff into huge crates, turning his apartment into an obstacle course that’s even more annoying to navigate.

After disappointing sales, the Belgian developers wrote, in a blog post overflowing with frustration: “We really did our best with Sunset, our very best. And we failed.” I picked Sunset up in the virtual bargain bin and don’t regret it—but I cannot recommend it unless you’re intrigued by the premise and prepared to deal with its frustrations. If so, buy it on a sale.

Additional reading

- After Sunset by Nicholas O’Brien celebrates the game as an artistic achievement while critically examining the market as the primary way to support development of games like this one.

In Gwendy’s Button Box by Stephen King and Richard Chizmar (reviews), a young girl is entrusted with a magical box that can change the whole world—and that also dispenses delicious chocolate treats. The short novella is an allegory about power that stands entirely on its own.

With King’s permission, Richard Chizmar wrote a sequel anyway. In Gwendy’s Magic Feather, it’s 1999, and our protagonist Gwendy Peterson is now an elected Congresswoman. In this alternative history, some guy named Hamlin is US President and is bringing the country to the brink of war with North Korea.

(Record scratch, freeze frame.) You probably wonder how Gwendy ended up in this situation. Chizmar briefly catches us up in paragraphs such as this one:

Inspired by the AIDS-related death of her best friend, Gwendy resigns from the ad agency and spends the next eight months writing a non-fiction memoir about Jonathon’s inspiring life as a young gay man and the tragic circumstances of his passing.

An Academy Award winning documentary follows (because of course), and a politicized Gwendy goes to Washington. But the real action in the book doesn’t take place in DC, but in Castle Rock, Maine, site of frequent calamitous and supernatural events in King’s universe.

Back home over the Christmas break, Gwendy is briefed on the investigation of a series of child abductions that are terrorizing the community. Meanwhile, the button box has made another appearance in her life.

It’s a short book (224 pages in paperback), yet there are more subplots: about Gwendy’s husband, who is a photojournalist on assignment in Timor; about an illness in her family; about the magic feather from the title. It all feels hurried and unfocused, and before you know it, some threads collapse, others remain unresolved, and the book is over.

It remains to be seen if Chizmar and King can offer some more payoff with the planned last book in the trilogy, Gwendy’s Final Task, which will again be a collaboration between the two storytellers. On its own, Gwendy’s Magic Feather will likely keep you turning pages, but may leave you feeling unsatisfied.

This is a great app. It might not be as polished and have as much of that just-works-ness as something like Google Maps, but consider that the map is stored locally on your phone. You’re not telling Google or some other giant tech company where you’re going. It’s also very flexible. You can add “favorite places” like bookmarks, tell it to remember your parking space, and even add Wikipedia annotations to landmarks.

Along with privacy comes the fact that there is bound to be room for improvement - and you have control over that. If something is missing or incorrect on the map, don’t throw up your hands and switch back to Waze or whatever you were using before. Remember that OpenStreetMap is edited by volunteers, kind of like Wikipedia. All you have to do is go to openstreetmap.org and start improving the map. Any changes you submit to OSM will soon be available as an update to the maps installed locally on your phone. If you see a mistake in Google maps, all you can do is submit a request for someone else to consider fixing it.

Pros: Privacy, flexibility, ability to edit maps, offline navigation

cons: maps take up a lot of storage. My maps take up a total of 1.24GB. UI might be confusing to some because of all the options and some general rough edges. Calculating a route might take a moment longer since the calculation is done by your phone’s CPU and not a remote server.

This was terrible. I get what they were going for. It’s two, refreshing summer flavors smashed together in a sugary juice drink. Not a bad idea, but I can’t believe this one got out of the lab. The watermelon is too weak to be noticeable in the face of lemon, but when looking for the watermelon flavor it was so disparate from the citrus as to be downright annoying when I actually found it.

Who the hell liked this enough to fill millions of bottles with it and distribute it to refrigerated shelves in presumably thousands of gas stations and convenience stores? Did Snapple even test this on humans before deciding to sell it to us?

The story of PLATO, a computer-based instruction system developed at the University of Illinois, is filled with extraordinary and nearly forgotten precedents in the modern history of computing: for real-time collaboration, multiplayer online gaming, and the beginnings of cyberculture—all in the 1970s.

In The Friendly Orange Glow, Brian Dear has synthesized a research effort spanning decades into the (thus far) definitive history of the PLATO system, its principal architects, its community, and its legacy.

According to Dear (an early user of the system), the book is the result of

over 7 million words of typed transcripts from 1000+ hours of recorded interviews, plus over 13000 emails, plus hundreds (maybe thousands, I’ve lost count) of other materials including magazine and newspaper articles, books, documents, pamplets, videos, photographs, and brochures.

Dear introduces key figures like Donald Bitzer (the charismatic “father of PLATO”) and Daniel Alpert (a longtime champion of the project) while documenting the project’s development stages, from minimalist beginnings to breakthroughs such as the creation of 512x512 resolution touchscreen (!) plasma displays and the TUTOR programming language.

Bitzer and his team fostered a creative, open environment in which high school kids experimented alongside older students and professors. As the PLATO community grew, it created tools for chat & discussion, becoming an online community that would ultimately draw in thousands of people.

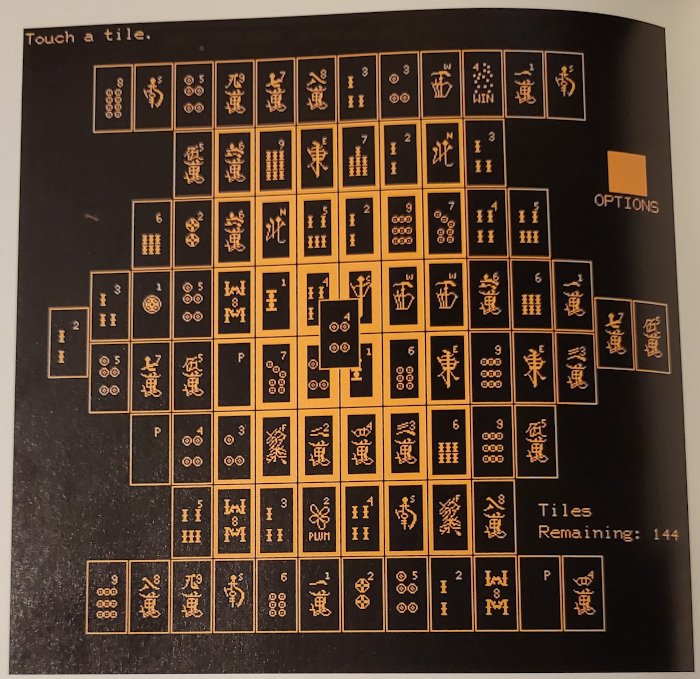

Brodie Lockard’s Mahjong game showcases the graphical capabilities of the system, which were far ahead of microcomputers from the same time period. (Credit: Brodie Lockard; scanned from the book. Fair use.)

Multiplayer Dungeon Crawling 101

As innovative and impressive as the graphical courses developed for PLATO were for the time, many of the most interesting uses of the system had little to do with education. Students used the PLATO terminals for real-time chatter, political organizing, journalism, storytelling, and—games, games, games.

These were multiplayer games with leaderboards and real-time chat, not tiny diversions like NIBBLES.BAS that would later be included with MS-DOS and played by millions of kids. In Empire, players competed to take over the whole galaxy; in Moria, they explored a dynamically generated dungeon (rendered as a tiny 3D wireframe).

The most inspiring story from the book is that of Brodie Lockard. After he became paralyzed as a result of a horrible sports accident, Lockard learned how to use a mouth stick to control a PLATO terminal. Through countless hours of painstaking effort, he created a gorgeous Mahjong game. Later, he (no less painstakingly) re-implemented it for the early Apple Mac under the name Shanghai, and it became a global smash hit for many platforms.

Peering into PLATO’s cave

What was PLATO’s pioneering online community like? How did it behave towards its members? While Brian Dear touches on these questions, this is also an aspect of PLATO examined by researcher Joy Rankin, including in her book A People’s History of Computing.

Rankin has found examples of abusive comments in PLATO’s archives, such as a misogynistic joke that should get a person fired in any professional environment. Prior to the publication of their respective books, Brian Dear wrote a detailed, confrontational critique of several of Rankin’s interpretations (accusing her of “misunderstandings, historical errors, omissions, and confirmation bias”), and things escalated from there.

That’s regrettable, because an examination of PLATO’s community norms and gender dynamics should be part of a comprehensive history of the system. To fill this gap, readers are well-advised to make up their own minds about the evidence that Rankin and Dear have presented.

A legacy of living ideas

In the 1980s and 1990s, PLATO could could well have reached millions of users, much as CompuServe and AOL did years later. As Dear documents in somewhat excruciating detail, the commercialization of the system was botched by Control Data Corporation, whose executives dismissed PLATO’s most innovative uses and regarded microcomputers as annoying toys.

Still, PLATO influenced thousands of minds, and Dear makes it clear that its legacy is far greater than an interesting historical footnote. The people who wrote lessons, apps and games on PLATO would go on to create their own milestones in computing history, from Lotus Notes to Wizardry.

At 640 pages (hardcover), The Friendly Orange Glow is a hefty tome. It could have been 100 pages shorter without losing anything essential—perhaps in exchange for some more analysis of the aforementioned community dynamics. Nonetheless, an accurate modern history of technology and cyberculture must look beyond Silicon Valley, and Brian Dear’s book is an important contribution to such a broader view.