Reviews by Eloquence

You may never have heard of the Wellcome Trust, but with a £20.9B ($26.7B) endowment, it is one of the largest philanthropies and the largest non-government funder of health research in the world. Established in 1936 after the death of American British pharma magnate Henry Wellcome, it has retooled itself into a modern science funder and promoter of open access to scientific research.

Beyond direct funding for research, Wellcome also supports science communication projects, and Mosaic is an in-house effort launched in 2014 to publish “compelling stories that explore the science of life.”

The model is simple: every week, Mosaic publishes a long-form story or other journalistic work. Some examples:

-

a look at kangaroo care, a child care concept for pre-term babies pioneered in Colombia,

-

an investigation of the work of Robert G. Heath and his almost forgotten research. Heath implanted electrodes in human brains and gave them the ability to self-stimulate their pleasure center. He also attempted to “cure” homosexuals.

-

an overview of the current state of thinking about animal intelligence.

These articles are written for a general audience. They would be right at home in, say, the New Yorker, but might be a bit too light on details for Scientific American. Illustrations are often artistic rather than technical. There is some podcast and video content as well.

Occasionally, Mosaic experiments with data journalism. A good example is the Global Health Check, which is a nice way to explore how health indicators have changed since the year of one’s birth.

Other Aspects

The site design is entirely inoffensive, and some of the illustrations are quite beautiful.

Given the financial position of its parent organization, you won’t find any ads or donate buttons on the site. You also won’t find a lot of information about Mosaic’s organizational internals (though there are mountains of documents about Wellcome itself).

The site design is unremarkable and easy to navigate. It works well on mobile devices and without JavaScript.

Mosaic is described as editorially independent, and its reporting goes beyond projects Wellcome funds. I did find disclosure statements where appropriate. It’s also nice to see that every person involved with a story is credited at the bottom of each story (author, editor, copyeditor, fact checker, art director, illustrator, etc.), a practice I’d encourage other media to emulate.

Consistent with Wellcome’s open access policy, Mosaic content is under the Creative Commons Attribution License, allowing anyone to re-use it for any purpose provided credit is given.

The Verdict

If you’re at all interested in life science, I can’t think of any reason not to follow Mosaic’s work. It’s fairly easy to decide whether the weekly story is something you care about, and if it is, the journalism is generally of very high quality and a pleasure to read.

The focus of Mosaic is on the process of scientific exploration, on the scientists and caregivers, and on the lives impacted by their work. There’s room for improvement in how more technical aspects and key takeaways are conveyed. Call-outs or sidebars summarizing key concepts of an article might help readers who are short on time, or who just want a bit more than a teaser before deciding to spend 30-60 minutes on a story.

You can follow Mosaic on social media (Twitter, Facebook) to get updates and reposts, or you can subscribe via email to get only the new stuff. They’re also part of our Twitter list of quality nonprofit media. The rating is 4 out of 5 stars: recommended.

If you’ve been online since the late 90s, you probably have known about CounterPunch for a while. After 9/11, it became one of the primary sources for non-mainstream information about US foreign policy, while usually staying clear of the most absurd conspiracy theories.

The project was started as a print newsletter by Ken Silverstein in December 1993 (1993-2011 archives). A one-year subscription to 6 issues of the 36-page newsletter currently clocks in at $50 for US residents. Website content is unrestricted and ad-free.

I would situate the politics of CounterPunch on the antiwar far left (think Ralph Nader/Jill Stein), with some curious contradictions. For example, co-founding editor Alexander Cockburn (deceased in 2012) did not believe in climate change and opposed gun control.

The nonprofit organization behind the site (incorporated as the “Institute for the Advancement of Journalistic Clarity” in California) is as small as you might expect; it reported revenue of $427K in 2015, and did not report any employee compensation, suggesting a shoestring operation.

Unsurprisingly for a tiny org, there’s not much in the way of organizational transparency on the CounterPunch website: no reports, no financial statements, no link to the tax returns.

Content

CounterPunch primarily publishes analysis and opinion rather than original news reporting. Its writers include journalists and authors, activists and academics. It publishes a lot of material – the current “weekend edition” contains 45 articles, some exclusively published on CounterPunch, others cross-posted elsewhere.

The site doesn’t make much of an effort to organize this flood of information. The latest headlines are listed in the sidebar, and excerpts from selected articles in the middle column. The reader has to navigate opaque headlines like “We Aren’t Even Trying”, often without any additional context other than the author’s name.

Editing is hit-or-miss, and citations are few and far between. The website is more of a group blog than a journalistic enterprise, and to get value out of it, readers need to become familiar with the authors whose judgment they trust.

The site covers international politics with special focus on US domestic and foreign policy. There’s no meaningful distinction between types of content (e.g., news vs. opinion), and it’s not unusual for posts to adopt disparaging monikers like “Killary” (for Hillary Clinton), or to ascribe malevolence to political actors. Example:

“And certainly Sanders’s Iraq vote suggests he is not as reckless or bloodthirsty as Killary, but that is setting the bar somewhere beneath the belly of a viper.”

The tone is set at the top – editor Jeffrey St. Clair, too, uses monikers like “MSDNC” (for MSNBC) or “Hillaroids” (for Hillary Clinton supporters).

Positioning, Bias

The underlying perspective shared by many CounterPunch writers is that the leading political forces in the US are equally bad. Individuals like Julian Assange who express viewpoints opposing the US are uncritically celebrated. Here are a few headlines about Assange (who has also published on the site):

- “Julian Assange is a Political Prisoner Who Has Exposed Government Crimes and Atrocities” by Mark Weisbrot (2017)

- “New York Times Shames Itself By Attacking Wikileaks’ Assange” by Dave Lindorff (2016)

- “Julian Assange: the Untold Story of an Epic Struggle for Justice” by John Pilger (2015)

- “Why Julian Assange is My Hero” by Jennifer van Bergen (2010)

- “Julian Assange: Wanted by the Empire, Dead or Alive” by Alexander Cockburn (2010)

This hyperpartisan cheerleadership facilitates the spread of misinformation. For example, CounterPunch also published “Droning Assange: the Clinton Formula”, which was based on a story by True Pundit, a fake news site in the narrowest sense of the term (the made-up claim was uncritically repeated by site editor Jeffrey St. Clair).

It also ignores the many criticisms that have been raised about Wikileaks, which turned itself into a propaganda machine for the alt-right in the 2016 election cycle, up to and including proliferation of complete nonsense such as the infamous “Spirit Cooking” tweet.

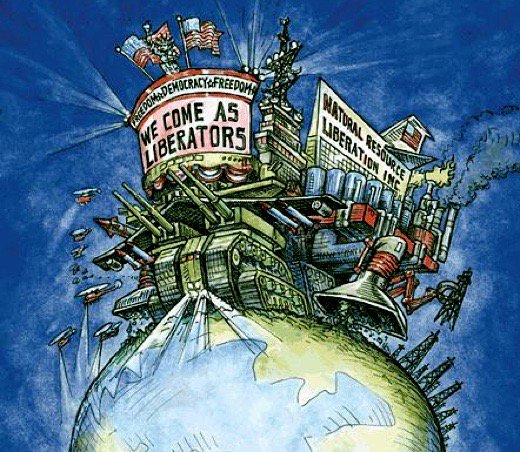

Generally, CounterPunch publishes material consistent with a specific narrative: the US is the world’s dominant superpower, and therefore global issues can usually be traced to American action and inaction; in contrast, claims about misbehavior by countries not aligned with the US should be regarded with extreme skepticism. This view can perhaps be best summed up with this image shared via the site’s Twitter account:

How CounterPunch views the world. Source

Consistent with that idea, CounterPunch is receptive to apologia for dictators the US doesn’t like – it has published numerous stories defending Venezuela’s increasingly brutal and corrupt regime, for example. In extreme cases like the Syria conflict, it has published bizarre pro-Russian propaganda pieces such as William Blum’s oeuvre. In one recent article titled “The United States and the Russian Devil: 1917-2017”, Blum writes:

The same Western media has routinely charged Putin with murdering journalists but doesn’t remind its audience of the American record in this regard. The American military, in the course of its wars in recent decades, has been responsible for the deliberate deaths of many journalists. In Iraq, for example, there’s the Wikileaks 2007 video, exposed by Chelsea Manning, of the cold-blooded murder of two Reuters journalists; the 2003 US air-to-surface missile attack on the offices of Al Jazeera in Baghdad that left three journalists dead and four wounded; and the American firing on Baghdad’s Hotel Palestine, a known journalist residence, the same year that killed two foreign news cameramen.

There is in fact no evidence that journalists were specifically targeted (“deliberate deaths”) in the incident exposed by Wikileaks or the firing on the hotel. A much stronger case can be made that the attack on Al Jazeera was deliberate, and indeed US right-wing media agitated in favor of such attacks at the time, labeling Al Jazeera “enemy media”. If intentional, this certainly was an immoral and illegal attack.

A fair comparison would look at Russia’s own record in wartime and in peacetime, including the staggering list of journalists murdered within Russia. But a fair comparison is clearly not what Blum is aiming for.

In an aside, Blum credits Donald Trump for “not [being] politically correct when it came to fighting the Islamic State.” This is the same Trump who campaigned on the promise of murdering terrorists’ families. As for Russia’s own imperialist ambitions? Here’s Blum’s pro-Putin take:

Lastly, after the United States overthrew the Ukrainian government in 2014, Putin was obliged to intervene on behalf of threatened ethnic Russians in Crimea and eastern Ukraine. That, in turn, was transformed by the Western media into a “Russian invasion”.

In this view of the world, actions by actors the US dislikes are almost always defensible when viewed in light of alleged American behavior. That is not to say that the antiwar perspective isn’t useful – of course it is. But many of the writers CounterPunch publishes tend towards dogma, disinformation and rhetoric more than rigorous analysis, which makes the site, at best, a mixed bag.

At its worst, it enables demagogues. For example, CounterPunch routinely publishes Israel Shamir’s writings (including an execrable defense of Pol Pot). On his own website, Shamir has published an essay about Holocaust denier David Irving (emphasis original):

Technically, David Irving was sentenced for so-called “holocaust denial”. But the concept of Jewish holocaust being the only enforced dogma of supposedly secular Europe has little to do with the Second World War and its atrocities.

(…)

They say that even their death is not like the death of anybody else. We must deny the concept of Holocaust without doubt and hesitation, even if every story of Holocaust down to the most fantastic invention of Wiesel were absolutely true.

(…)

European history went full circle: from rejecting the rule of Church and embracing free thought, to the new Jewish mind-control on a world scale.

There’s not much to say here – no defense of this anti-Semitic rubbish is possible. Yet, CounterPunch has published more than 50 posts by the person who wrote these words.

Other Aspects

As noted, the website design overall is minimal and doesn’t aid discovery. Articles are usually just text; image embeds are often low-resolution, and other types of embeds (charts, interactive maps, etc.) are nowhere to be found.

The site works reasonably well on mobile devices. It refers to its Facebook presence for discussions, which is not a bad move – however imperfect, Facebook’s ranking algorithms at least mean that some of the better comments will come out.

CounterPunch content is under conventional copyright.

The Verdict

If you are looking for sources that help you understand what is going on in the world, I cannot recommend CounterPunch. Reading it may be cathartic if you share the specific views evinced by many of its writers, but the occasional bit of well-researched reporting is drowned out by one-sided commentary and analysis.

The site’s willingness to offer a platform to writers like Shamir suggests either very sloppy oversight or, worse, sympathies for anti-Semitic views. Either way, it makes the site less useful as a source to be cited and shared.

Evidence like the proliferation of the “Drone this Guy” story shows that even obviously made-up nonsense will not be weeded out reliably. Caveat lector applies – if you do rely on CounterPunch material, track down sources and verify that they really say what the author claims.

This is obviously not a criticism of every writer who publishes on CounterPunch. The site has been around for a long time and has attracted many widely respected left-wing and antiwar intellectuals. Project Censored, which does good work highlighting stories underreported in major media, has recommended a few CounterPunch pieces over the years.

However, since the 90s, many much more interesting alternatives have emerged, for example:

- Common Dreams and Truth Out publish many writers from the antiwar left, but are more carefully edited and curated;

- The Intercept and New Internationalist provide in-depth original reporting on international war and social justice issues;

- Jacobin publishes explicitly socialist perspectives on current and historical events, while being usually reliably in opposition to all forms of authoritarianism.

2 out of 5 stars, with points off for poor editing, sensationalism, misinformation, and distortion through extreme one-sidedness.

Thimbleweed Park is a newly released cross-platform adventure game that was funded in large part through a 2014 Kickstarter campaign. Its creators – Ron Gilbert, Gary Winnick, David Fox, and others – are the directors and designers of some of the most celebrated point-and-click adventure games of all time, including Maniac Mansion, Zak McKracken, and The Secret of Monkey Island.

Their mission was to create a game that should feel like an archaeological discovery from the late 1980s, rather than a brand new game. Emphasis on “feel”, because Thimbleweed Park is meant to evoke memories rather than replicating them. For example, while it uses beautiful low resolution pixel art, it also employs more modern visual and sound effects to enrich the game environment. All the text is spoken by voice actors.

Setting and Game Mechanics

The game starts as a “whodunit”. Detectives Angela Ray and Antonio Reyes are trying to find a killer in the tiny town of Thimbleweed Park. Over time, we discover their own concealed motives, as well as a much larger mystery. The player can switch between an increasing number of characters as the story develops.

The game mechanics combine the familiar verb-object logic of most LucasArts adventure games (“Use Sushi in glass with lamp”) with some new elements such as character-specific to-do lists that help keep you on track.

Each of the game’s playable characters has their own voice, their own behavioral quirks, their own dialog, and so on. This is Ransome the Clown, for example, a disgraced insult comic. He carries itch cream with him that appears to serve no purpose but to produce an animation when applied.

The game is chock full of little jokes and distractions like this one. The actual puzzles the player has to solve are similar to the ones you may be familiar with from the genre: pick up items, combine items with other items, push/pull objects visible on the screen, use differences between the characters to your advantage.

While you should keep pen and paper handy, none of the puzzles are unfair, none rely on excessive pixel-hunting, and it’s near-impossible to die. Nor can you end up in a dead-end situation – there’s always a way to progress in the story.

That said, the game can’t cure some genre-typical ills. You might sometimes get stuck trying to solve a puzzle before the plot has advanced sufficiently to let you do so, for example. Item combinations that should work produce no meaningful effect. And some puzzles are a bit silly (at one point, we have to search the whole town for a dime to use in a payphone).

Dialog and Plot

You can “talk to” characters all over Thimbleweed Park, and doing so may yield helpful hints or move the plot forward. As is typical, dialog consists of selecting one of multiple dialog lines in response to what another character says; often, you’ll find yourself clicking through all possible options.

Don’t expect laugh-out-loud humor in every interaction – there are plenty of little jokes, but much of the dialog simply expands on the backstory of a character or the town. It does so well, though the town’s small stories quickly have to make way for the larger plot.

The playable characters generally can’t talk to each other; the dialog between them is largely left to the player’s imagination.

Depth

All the action takes place within the town of Thimbleweed Park itself, but the game world is big enough to keep you engaged. Some scenes are visually rich but don’t let you do very much, though I suspect I missed a few Easter eggs along the way.

The level of detail in the game is astonishing, and much of it is in service to the fans and backers of the game. For example, the in-game phone book contains the names of all backers above a certain level, and each of them had the option to record a (spoken!) voicemail message for the game, which plays if you dial the number on an in-game phone.

Similarly, the in-game library contains hundreds of unique “books” – we only see two pages per book – written by fans of the game. They’re even loosely categorized and range from little poems to short stories and amusing pseudo-excerpts.

That said, beyond details and Easter eggs, the replay value of the game is limited. This is true for most point and click games: the game is more or less “on rails” and the level of real choice is limited. Think of it more like a movie you might watch again years later than a game you’ll keep playing.

The Verdict

If you enjoyed the point-and-click games of the late 1980s and early 1990s, then buying this game is a no-brainer. It stands on its own and delivers an interesting story and a lot of classic adventure puzzle fun.

It’s not perfect, but the imperfections are minor. The game might have been better with 1-2 fewer playable characters and a more coherent story to connect them to each other – Day of the Tentacle got that balance exactly right, while Thimbleweed Park falls a little short in that regard.

The game has many in-game references to video games and programming, and to the specific games Gilbert/Winnick/Fox made. This isn’t obsessive self-referencing – it’s pure affection. Much of the game is a love letter to the genre and to the fans who grew up playing these games, giving it an intimate feel that may be a little off-putting to folks who’ve never played any of them.

If Thimbleweed Park does look interesting to you but you’re new to this world of games, I’d recommend playing a few of the classics first. You can play the originals through ScummVM and in some cases buy modern remastered versions. My personal recommendation would be to play in this order:

-

The Secret of Monkey Island (I’m not a fan of the remastered graphics, but the GOG version includes the original graphics as well)

-

Zak McKracken (you can get a 256 color version on GOG that was originally made for an obscure Japanese console)

-

Day of the Tentacle and the predecessor Maniac Mansion (both included in the GOG version; warning: Maniac Mansion has a high frustration level)

-

Thimbleweed Park (GOG version)

As this list shows, I consider Thimbleweed Park to be a proper addition to this ensemble of games. The $20 price may seem a bit steep by the standards of casual gamers, but this is a big game, and if it does well, it will help keep the genre alive.

As someone who’s played many point-and-click games, I would give Thimbleweed Park 4.5 stars, rounded up because of the love that went into it; if you’ve never played a point-and-click before, I think you’ll still get a 4 star game out of it.

If you use any of the many content management or blogging platforms that are powered by the markdown, you may eventually find yourself wishing for a more pleasurable editing environment. Sure, markdown is pretty easy to learn, but the more complex a document gets, the higher the cognitive load of translating mentally between markdown and the formatted result.

Many markdown editors don’t change the actual editing experience and instead use side-by-side live preview to show what’s going on; others try to combine formatting and WYSIWYG into one ugly mess. Typora’s approach is different. It follows the “distraction-free” writing philosophy and largely gets out of your way – while offering powerful functionality when needed.

Documents look as if they’re fully WYSIWYG, but markdown magically transforms as you type:

For some markup, entering that part of the text with your cursor reveals the underlying markup:

There are lots of neat little tricks that make the editor pleasurable to use. For example, let’s say you have a link in your clipboard. If you select a piece of text and press the link shortcut (on my system, Ctrl+K), the URL copied into your clipboard is added. While this may initially be confusing, as you anticipate this behavior, you can adjust your workflow and get a small productivity benefit:

The editor supports markup extensions such as math and tables. The table editor is fully WYSIWYG and very easy to use (tables in any markup language are a pain). You may have to turn off some of these features if they interfere with regular writing. The $ symbol was giving me trouble until I disabled math – having this enabled by default may not be a good idea.

As of this writing, Typora is still in beta, and while it is, it’s a free download for Linux, OS X, and Windows. Since I generally prefer free/open source software, I might not stick with it in the long run, but the thoughtful design choices are definitely impressive. If non-free software doesn’t bother you and you’re looking for a markdown editor, I recommend giving it a spin!

Of all the publications we’ve reviewed so far, Science News has by far the largest social media reach. With 2.27M followers on Twitter and 2.7M “likes” on Facebook, it easily outperforms many for-profit science outlets like LiveScience or SPACE.com, and is on par with Scientific American.

Granted, it’s had a bit of a head start. Science News has been in print since 1922 by the Society for Science and the Public. As the name suggests, Science News focused on giving updates on the latest scientific discoveries, but that includes some in-depth feature stories, as well. A print edition is issued every two weeks.

The online version includes a steady stream of mostly brief science updates alongside a set of staff blogs which effectively function as an analysis/opinion section.

Blog posts are available indefinitely, while articles become paywalled after a year (as of this writing, a digital-only Society membership that grants full archival access costs $25/year). You can also preview the print magazine before joining, a nice touch that I’d like to see other print publications adopt.

The organization also publishes Science News for Students, which targets “teens and tweens” and includes helpful glossaries in each article. Unlike the main site, its articles never get paywalled.

Funding, Compensation, Transparency

Per the latest available tax return, Science News had $18.6M in revenue in 2015. $6.5M of its expenses were allocated to Science News itself. In addition, the Society runs some of the largest science outreach projects in the country, each sponsored by a different corporation: the Intel Science and Engineering Fair, the Regeneron Science Talent Search and the Broadcom MASTERS science competition. Together, it spent $12.8M on these and other outreach programs.

CEO and President Maya Ajmera received $323K in total compensation including benefits in 2015. While a bit high by nonprofit standards, it’s well below the outliers we’ve reviewed (which are also smaller organizations). Ajmera brings impressive nonprofit credentials to the job: as a 25-year-old, she founded the Global Fund for Children, which has since grown into a large international grant-making organization. Editor-in-chief Eva Emerson received $200K in total compensation.

Unusually, the program areas such as the competitions generated 74% of the organization’s revenue in 2015 per the Annual Report, and the magazine only generated 23%. The report notes: “Print circulation declined 4.5 percent, to end the year with 84,548 paid subscribers. Despite the growth in digital readers, the magazine operates at a loss.”

Positioning, Coverage

The Society describes itself as being “focused on promoting the understanding and appreciation of science and the vital role it plays in human advancement: to inform, educate, and inspire.” Science in this context means primarily STEM – (natural) science, technology, engineering, and mathematics.

Its articles are typically written in a lighthearted tone, e.g.: “Dengue fever spreads in a neighborly way. Dengue is a bit of a homebody.” Some scientists may occasionally bristle at the publication’s liberal use of similes, but I did not encounter clickbait or sensationalism, nor did I find evidence of major inaccuracies.

The articles are typically short and illustrated, making the key conclusions easy to grasp. Cited papers are referenced directly, which isn’t necessarily a given in science reporting – other publications often reference an institution’s own press release, making it necessary to dig for the actual paper.

Science News generally stays away from political controversy and “science vs. pseudoscience” arguments. For example, a Google search for homeopathy yields no relevant article results (an internal search turns up the paywalled article “Dilutions or Delusion?” from all the way back in 1988). Homeopathy is obvious pseudoscience, so its exclusion is reasonable – but if you’re looking for arguments why something is or isn’t considered science, you might not find them here.

The publication did weigh in on the 2016 election with its own report: “See where Clinton and Trump stand on science”. It’s a neutral summary based on public statements and the responses to 20 questions posed by ScienceDebate.org, an independent effort the Society supports. In contrast to Scientific American (candidate assessments), Science News made no attempt to grade the candidates’ answers. Some might find its approach here a bit anemic and suffering from false balance, especially when considering the planetary stakes on issues like climate change.

Design, Licensing

Then and now: Science News in 1939 vs. today

The site’s design is straightforward, with a left-hand column showing the latest headlines, and a right-hand area featuring story summaries. There’s little clutter to distract from the content, and you can safely turn off your ad-blocker if you don’t mind an occasional splash screen. There are small “sponsor messages”, but they are largely self-referential, e.g., an ad for the Science News app.

The color scheme is a bit too low-contrast; some of the grey-on-grey text is difficult to read even without vision problems. The site works fine without JavaScript and on mobile devices.

Each story features a Disqus-powered comments section, and the Science News staff does moderate comments that violate its policies. In spite of that, the signal-to-noise ratio of comments isn’t very high, but you’ll occasionally find very knowledgeable commenters.

Predictably, content is under conventional copyright, though Science News makes heavy use of photos and illustrations from free/open repositories such as Wikimedia Commons.

The Verdict

Science News is a fine source of daily updates on STEM topics, and the Society’s many outreach efforts are laudable and important. Its coverage avoids controversy, meaning that you may need to look elsewhere for background science on highly politicized topics like abortion, or for debunking pseudoscience.

Like many traditional publications with origins in print and declining print subscriber numbers, it’s clearly still trying to figure out its place in the new media landscape, but the large amount of quality content it produces combined with its reputation and strong branding have already given it a highly impactful online presence.

Organizationally, the Society shows all the signs of a well-run traditional nonprofit, and its Annual Reports give a good overview of its activities.

With all that said, it’s a bit sad to see so much quality content disappear into restricted archives (and it makes linking a bit pointless in the long run, unless you want to go digging on archive.org). It would be good to see the organization experiment with models that enable it to keep more of its articles freely available. For content that’s permanently unrestricted (such as the Science News for Students website), releasing it under a free license seems to have no obvious downside.

The final rating is 4 out of 5 stars – Science News offers good summaries, but for depth and breadth, you may want to complement it with other science-focused sources.

Life by Daniel Espinosa is Alien-style space horror, but instead of the Nostromo, the action takes place closer to home. The small crew of the International Space Station is tasked with analyzing a sample returned from Mars. The sample contains living cells capable of developing into a multi-cellular organism, and said organism quickly starts causing trouble.

The first half of the movie works reasonably well, but the careless actions of the main characters and the predictable use of various horror tropes turn the movie into forgettable fare. The creature itself is interesting enough; the battle of wits between it and the bumbling astronauts that man the station makes one wonder whether Earth might not be better off being taken over by the critters.

The acting is passable, but if you’re hoping for a breakout performance from Jake Gyllenhaal, you’ll be disappointed. He’s phoning it in as Dr. David Jordan, an apathetic long term tenant of the station, though you could be forgiven for mistaking him for the station’s android. I found Ariyon Bakare most memorable as biologist Hugh Derry, but the script stopped short of giving him anything interesting to do.

What you’re left with is an okay thriller that has a few visually powerful moments and an interesting creature, but that otherwise adds nothing to the genre. There are many stories about alien life that still deserve telling; this one we could have done without. 3 stars.

While the scientific consensus is clear that human civilization is rapidly changing the climate through uncontrolled greenhouse gas emissions, details matter. Which regions will be hit hardest? Which natural disasters can be attributed to climate change? Do positive effects outweigh negative ones in some regions?

To tell this story accurately requires grappling with the latest scientific findings. Science/environment beat writers must do their best to translate these findings to their audiences. Sometimes the truth gets lost in translation, and important findings may be missed. Moreover, traditional media prefer reporting on the human drama of the moment (crime, politics, etc.), and climate change rarely gets the attention it merits.

Is there a better way? Climate Central combines climate science and climate journalism in a single nonprofit organization. It is less focused on the politics of climate change than, say, InsideClimate News (review), but it does cover policy interventions, as well.

It’s been fully operational since 2009 and is based in Princeton, New Jersey, near the famous university. That’s no coincidence. One of the organization’s biggest seed funders is Princeton alum Eric Schmidt (of Google/Alphabet fame), and several staff and Board members are Princeton-affiliated.

Funding and Compensation

The organization’s latest tax return shows revenue of $9.3M, which places it among the better-funded nonprofit journalism outfits.

Most of this funding comes from foundations, but the organization also lists government agencies such as NASA and the US Department of Energy among its supporters. Funding is not further broken down (by year/gift size), and multiple requests for details through the site’s contact form received no reply.

The organization does not publish Annual Reports, and there is no other page that speaks to impact of specific programs, with one exception: The “What We Do” page features a loose list of links to articles by many international publications which have featured Climate Central’s news and research.

Program expenses are split between journalism ($2.7M) and research ($2.2M). Executive compensation is very high by nonprofit journalism standards: CEO Paul Hanle received total compensation (including benefits) of $379K in 2014, Chief Scientist Dr. Heidi Cullen received $395K, and two (S)VPs received more than $280K in total comp.

Granting that Climate Central is an unsual organization, the Union of Concerned Scientists (based in Cambridge, MA – not much less expensive than Princeton) may serve as a useful additional benchmark. It is a much bigger organization, with $26.6M revenue in 2013-14 (tax return), yet its Executive Director received “only” $270K in total comp, and its Chief Climate Scientist (who was one of the Lead Writers of an IPCC report) received $186K.

Sampling the News Feed

-

“Trump and Automakers Target EPA Mileage Rules” is a typical Climate Central news story. It neutrally summarizes how the Trump administration is following through on a campaign commitment to roll back EPA rules implemented towards the end of Obama’s second term, and quotes both environmental experts, an auto industry lobby group, and an environmental advocacy group. (There’s nothing wrong with quoting industry lobby groups, as long as their interests are clearly identified. Problems arise when dealing with “think tanks” that act as corporate front groups, pretending nonpartisanship.)

-

“Polluters Could ‘More Easily’ Commit Crimes Under Cuts” examines the Trump administration’s proposed EPA budget. Importantly, it highlights some landmark EPA settlements and the complexity of cross-state pollution by large corporations, which refutes the idea that a state-level regulatory approach is sufficient. Again, the article is neutrally written and cites multiple voices, largely focusing on expert opinion.

-

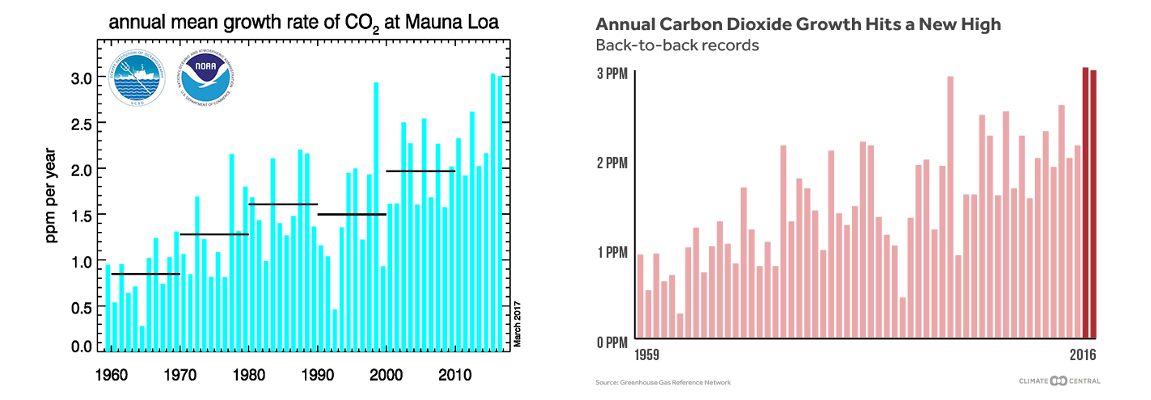

“Carbon Dioxide Is Rising at Record Rates” cites recent measurements of the carbon dioxide concentration and is partially based on a press release by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Climate Central includes its own simplified version of the NOAA chart (see below) and adds useful additional data and context.

The NOAA version of the chart vs. the Climate Central version. To simplify it, Climate Central removed tick marks, labels for in-between years, and 10-year average bars, and highlighted the most recent years. The most idiosyncratic of these changes is the removal of the year labels; most publications show at least some in-between year markers for time series data (NYT example, Vox example, Bloomberg example).

Other Projects

Beyond its news feed, Climate Central makes efforts to translate its own research into explanatory journalism. Sea Level Rise is one such example project. It is based on peer reviewed research such as the paper “Carbon choices determine US cities committed to futures below sea level”, and translates these findings into interactive visualizations.

An example of these visualizations is the “Seeing Choices” map which displays the sea level rise in cities like New York under different temperature scenarios.

Some news feed stories also feature interactive content, such as “Meltdown: More Rain, Less Snow as the World Warms”. Many of these interactive widgets are embeddable, though they don’t offer the rich set of share/embed/download options a site like Our World in Data does.

I didn’t find a list of all papers published by Climate Central scientists, or an open access policy, though the papers that are referenced do appear to be freely available online.

Design and Licensing

The main website doesn’t have a mobile version (a pretty major fail in 2017), and it is a bit cluttered with many sections competing for attention (“featured content”, “climate services”, “special sections”, etc.), drowning out the news portion of the site. Perhaps to make up for that, a large story carousel features the latest headlines.

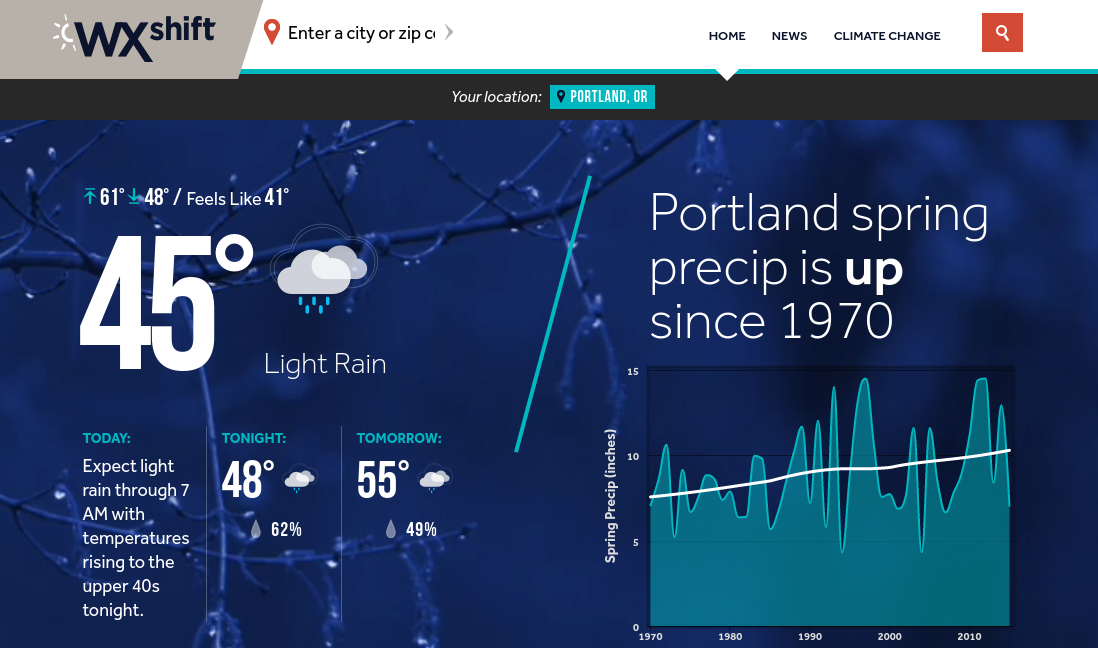

wxshift provides local weather information in combination with longer term climate data and other climate change context. While much more visually appealing than Climate Central, it does not appear to have much of an audience yet.

Climate Central has created much slicker story-centric designs for some of its feature reporting (example). It also operates wxshift, which combines weather reporting with context about how climate change is impacting the weather. Some of the main site’s news content is mirrored to wxshift, as well. Launched in 2015, it appears to have only a very small audience (as of this writing, it has 1,751 Twitter followers and barely registers on traffic ranking tools like Alexa).

Climate Central’s content licensing page is restrictive, requiring case-by-case permission requests rather than using a free license for some or all content. This is fairly typical; even among nonprofits, permissive licensing terms are the exception, not the norm. The organization goes through a lot of trouble to create graphics and maps, which would be entirely appropriate in reference works like Wikipedia, where they could be added to articles read by millions – but the restrictive copyright terms make that kind of re-use impossible.

The Verdict

Climate Central’s journalism+science approach usefully complements more politically focused sites like InsideClimate News. Its journalism is nonpartisan, understandable, and fair, while being based on the scientific consensus. If you care about climate change (and unless you are reading this from another planet than Earth, you should), it’s a source worth adding to your social media or RSS reader.

The main site could use an upgrade. While it’s certainly non-trivial to upgrade older sites, there are many open source projects specifically targeting nonprofit journalism, such as the Institute for Nonprofit News’ widely used Largo Wordpress theme and the Ghost publishing platform.

The organization would also benefit from greater transparency. Being open and accountable about how impact is measured and under what conditions projects are shut down can help donors appreciate that their support is put to good use, and that projects aren’t just left to spin even if they aren’t producing a lot of bang for the buck.

The rating is 4 out of 5 stars, with high marks for the overall quality of Climate Central’s journalism. 1 point off for lack of organizational transparency, for executive compensation well above other science and journalism nonprofits, and for a site design that is not consistently mobile-friendly.

Stranger Things is one of last year’s big Netflix hits. We finally found the time to watch the first season and quite enjoyed it.

The series borrows liberally from many 1970s-1980s books and movies (Stephen King’s “Firestarter”, Richard Donner’s “The Goonies”, Ridley Scott’s “Alien”) to tell its story of a bunch of kids investigating the disappearance of a friend. They are up against evil government agents and, well, stranger things.

This could have turned into a series of tropes, but the talented actors (kids and adults alike), the well-paced plot, and the lovingly crafted sets and special effects make the show a joy to watch from start to finish. David Harbour shines as Police Chief Jim Hopper, gradually revealing his character’s depth. Winona Ryder plays the distressed mother Joyce Byers convincingly, though a little bit less distress would have worked just as well.

The kid actors all do an admirable job, but Millie Bobbby Brown (El) and Gaten Matarazzo (Dustin) give especially memorable performances. The show’s weakest bits involve some bog standard high school drama, and the cardboard character government agents.

The show references its inspirations, but not in an obnoxious way. Stephen King is once mentioned by name, and other 80s pop culture bits are woven into the story where appropriate. Beyond that, there are many elegant visual references (link contains spoilers) .

If you haven’t gotten around to it, I definitely recommend watching the first season. You’ll be quickly pulled in, and if you grew up during the 80s, you might laugh out loud a few times, quite possibly confusing the hell out of any younger folks present.

(Full disclosure: As of February 2018, I work for the Freedom of the Press Foundation, which develops SecureDrop. This review was written almost a year before then and reflects only my personal opinion at the time. I do not intend to update it.)

There’s little doubt that Donald Trump owes a large debt to Wikileaks. In 2016, the site systematically and incrementally released a stream of hacked emails about Trump’s political opponent through the final weeks of the 2016 presidential campaign, while not releasing any materials about Trump himself. Defenders believe that Wikileaks simply releases what it gets its hands on, but its Twitter account, as well as the targeted timing of past releases, speak to clear political intentions.

Wikileaks has repeatedly disseminated conspiracy theories, spread info from fake news sites, even weighed in with its “hot takes” on the vice presidential debate. It has ignored Trump scandals while joining alt-right speculation about Hillary Clinton’s health. As I write this, its most recent tweet is not about, say, an example of corruption in the Trump administration, but yet another Podesta email.

Political bias aside, Wikileaks has also been frequently criticized for its lack of curation, including by NSA whistleblower Edward Snowden (“their hostility to even modest curation is a mistake”) and by progressive activist/scholar Lawrence Lessig. It has overhyped leaks and dismissed valid concerns about linking to a “doxing” site. It has carelessly flirted with anti-Semitic tropes in its commentary.

So what’s the alternative? The late Aaron Swartz knew that tools for whistleblowers would become increasingly important and started a project called “Deaddrop”, an open source platform for secure communication between whistleblowers and media. After his death, development has been taken up by the Freedom of the Press Foundation.

Unlike Wikileaks, SecureDrop is a piece of software, not an actual site to leak to. It can be installed by any media organization that wants to make itself accessible to whistleblowers beyond accepting anonymous brown envelopes. Under the hood, SecureDrop uses the anonymous Tor network, to allow sources to connect to media organizations while significantly mitigating the risk of discovery.

Sources are assigned a code phrase they can use for additional document uploads and two-way communication. I haven’t leaked anything, but I’ve walked through the first bits of the user flow and can confirm that, from the source’s point of view, it’s very easy to use. (Of course, there are still many risks when dealing with confidential/sensitive information, including digital fingerprints that could give away a whistleblower’s identity.)

SecureDrop has since been installed by countless media organizations: the New York Times, the Associated Press, the Washington Post the CBC, ProPublica, the New Yorker, The Intercept, VICE Media, The Guardian, and many others. The site offers a helpful directory of all of them.

Does it work? David Fahrenthold thinks so. He is the Washington Post reporter who broke the story about Trump bragging about being able to sexually assault women with impunity, and who also reported extensively on many legally and ethically questionable activities of the Trump Foundation. In October 2016, he tweeted meaningfully: “It works. I know.”

He’s not alone. An in-depth report by the Tow Center for Digital Journalism concludes:

I spoke to representatives of ten news organizations for this study, and nine told me that they regularly receive useful tips or publish stories based on information provided to them directly through SecureDrop.

While any submission system like this is bound to also draw in crackpots and nonsense, “most reporters were adamant that the trouble of installing and maintaining a SecureDrop system has been worth it, whether it is measured on journalistic value, financial return, or moral principle.”

The software has already been independently audited four times, is fully open source, and managed by a small nonprofit (you can donate here).

The alternative to Wikileaks, then, is not simply yet another website. It’s a piece of software that, like a webserver, can be installed by any journalistic organization, giving whistleblowers full control over whom to trust with a given piece of information. And that alternative isn’t one we have to wait for. It exists today.

True to Aaron Swartz’s vision, there is now a decentralized set of secure drop boxes that whistleblowers can choose from. The idea of a central uber-platform for leaks – one which doesn’t hesitate to abuse its standing for political purposes – is obsolete. It’s time, in other words, to kick Wikileaks to the curb.

The scientific consensus is clear, the predictions range from bad to worse: we are slowly heating the Earth by pumping greenhouse gases into its atmosphere, with increasingly disastrous consequences. Yet politicians whose careers depend on fossil fuel industry support are as eager as ever to peddle doubt and uncertainty to justify inaction.

In US politics, the governing political party is now fully identified with climate denial. In the media, organized denial continues to this day in publications ranging from center-right (Wall Street Journal) to “alt-right” (Breitbart). See the chapter on organized climate change denial in the Oxford Handbook of Climate Change and Society for a scholarly overview of the machinery of denial.

How should journalists tackle the issue? Not, many scientists warn, by engaging in false balance, but by giving consistent and serious attention to the matter. So far, such warnings have fallen on deaf ears in the US. Never mind balance: not a single question in the US presidential debates focused on climate change, and the ultimately successful candidate has repeatedly called it a hoax.

InsideClimate News (ICN) is one nonprofit news site that wants to close the gap between environmentalist advocacy and the limited reporting on climate change by major media. Explicitly nonpartisan, it has won multiple awards for its journalistic work, including a Pulitzer prize for “The Dilbit Disaster: Inside The Biggest Oil Spill You’ve Never Heard Of”. That article series was the result of a seven month investigation into a pipeline spill of diluted bitumen (dilbit), and the expensive and unprecendented cleanup that followed.

The site was founded by David Sassoon, a former PR industry professional, in 2007. The American Press Institute interviewed him on the occasion of the Pulitzer award, and he provided some background on his motivation to start the site:

Back in 2007 it looked like the country was getting ready to move toward national climate legislation. And we were very much attuned to the interest in the business community and the economic case for taking action. We also saw that the mainstream reporting on climate change was flawed. It was still reporting as if there was equal doubt about man-made global warming — when really on one side you had politics and the other side science, which was indisputable.

The site transitioned from a small blog into a full journalism operation that built partnerships with Reuters, Bloomberg, The Weather Channel, VICE Media, and others. It was initially part of the nonprofit incubator NEO (formerly known as “Public Interest Projects”) and now operates as an independent organization.

Funding, Transparency, Executive Compensation

InsideClimate News has published a single Annual Report so far, for 2014. According to it, the organization spent $961K in 2014. 88% of revenue is attributed to foundations and 8% to individual/online donors. One nice touch: individual donors starting at the $10 level are listed by name. The website also lists foundation supporters, which include some common names like Ford, Rockefeller, and Knight, but also environmental funders such as the Leonardo DiCaprio Foundation and the Wallace Global Fund. Corporate sponsors like The North Face get logo placements on ICN’s website.

The Annual Report focuses more on what ICN does (showcasing especially its many media partnerships) than what impact its stories have accomplished in the real world. However, through 2016, ICN has published two newsletters, which do speak to impact. For example, from its April 2016 newsletter:

Although our Exxon: The Road Not Taken series launched last September, its momentum continues. Not only have the original set of stories won a series of journalism awards, they helped kick-start a push to investigate whether Exxon misled the public and investors on climate, with several states and the U.S. Virgin Islands now joining New York Attorney General Eric Schneiderman in the effort.

In an email, David Sassoon told me that the organization is shifting to releasing a full report in even years, supplemented by quarterly reports in odd years. He also suggested that previously distributed quarterly reports would be added to the public archive soon.

In ICN’s 2014 tax return (which shows $1.5M in revenue), Sassoon’s compensation is listed at $98,400 total, and writers are listed at $51K-$76K/year. Assuming this covers a full year of compensation, this is at the bottom end of organizations we’ve reviewed, though ICN is also one of the smallest organizations we’ve looked at in terms of revenue.

Right-Wing and Fossil Fuel Industry Attacks

It’s worth noting that ICN has come under attack from right-wing groups. In 2015, Jillian Kay Melchior wrote the article “InsideClimate News: Journalism or Green PR?” for National Review, a conservative paper which endorsed Ted Cruz (“Climate change is not science, it’s religion”) for President in 2016.

The critique doesn’t withstand cursory scrutiny and rests on ICN’s long existence as a small-scale effort bootstrapped with help from a nonprofit incubator and Sassoon himself. But it is bolstered by groups like the Media Research Center, which receives most of its funding from Breitbart/Trump-aligned billionaire Robert Mercer and has also cashed in hundreds of thousands of dollars from – wait for it – ExxonMobil.

To be sure, the fossil fuel industry really, really doesn’t like InsideClimate News. In addition to the aforementioned proxies, it regularly feuds with the small nonprofit through its own PR arms such as ExxonMobil Perspectives (examples) and Koch Facts (examples).

The goal here is probably not to convince environmentalists or even right-wing activists, as these websites receive tiny amounts of traffic, but to disrupt partnerships and funding, and to firmly push ICN into the categorization of “advocacy journalism” in order to undermine its journalistic credibility.

Positioning, Bias

As noted, ICN considers itself nonpartisan, but starts with the assumptions that there is no ongoing international conspiracy to perpetuate the climate change hoax and conceal its origins, and that the scientific community generally has an idea what it’s talking about. If you think those are reasonable assumptions (and – surprise, surprise – I do), that still leaves some important questions:

- Does ICN report on legitimate scientific disagreements?

- Does ICN report on legitimate policy disagreements?

- Does ICN treat the subjects it reports on (e.g., scientists, corporations) fairly?

Generally, ICN articles are written in a neutral tone. There are no parts of the site that are dedicated to activism. Compared to, say, Rewire (which we described to advocacy journalism in our review), this is a much more straightforward news site.

ICN staff sometimes write backgrounders such as “Republican Carbon Tax Proposal: Novel Climate Solution or Regulatory Giveaway?”. These are also not advocacy pieces – the article in question is a good example of balancing different perspectives, though it would benefit from citing sources.

Stories like “Warming Climate May Limit Lyme Disease’s Spread in Parts of the U.S.” clearly don’t serve an activist narrative. ICN also looks critically at the way scientific findings are used (“Both Sides in Climate War Blamed for Cherry-Picking Attribution Research”) and reports on ambivalent findings (“Study Delivers Good News, Bad News on Methane Leaks from Fracking Operations”). It includes fossil fuel industry voices/statements in some of its stories, as in this recent report on the Dakota Access Pipeline, even though industry spokespersons sometimes refuse to engage with ICN.

When it comes to renewables, the story “EPA Loopholes Allow Biomass to Emit More Toxic Air Pollutants Than Coal, Study Says” is an example of a critical look at a “renewable” technology (biomass) that is increasingly viewed critically, as recent reports on wood pellet energy schemes indicate. ICN also reports on carbon capture and storage and other technologies that could work in conjunction with fossil fuel use. At the same time, I found few stories on nuclear power, or on the ecological effects of large wind/solar projects. Similarly, I learned about the promising Allam cycle technology from Forbes – ICN has never mentioned it.

ICN does give most visibility to scientist and activist voices, and when it comes to climate change, tends to focus on stories that highlight risks of inaction, or show the potential of clean energy sources. Its in-depth coverage of the Environmental Protection Agency’s fracking study is a good example of its critical vantage point. Indeed, ICN sometimes describes itself as a source of “hard-hitting watchdog reporting”.

Content Example: “Exxon: The Road Not Taken”

One of the series that has gotten ICN into the crosshairs of ExxonMobil is “Exxon: The Road Not Taken”. In spite of ExxonMobil’s efforts to discredit ICN as a group of activists with an agenda, the series was named a finalist for the 2016 Pulitzer Prize.

Interestingly, ICN also offers the whole series as a Kindle ebook. Whatever one thinks of Amazon’s stranglehold on the ebook market, it’s certainly a convenient way to donate a buck and read the content on the go.

The series covers multiple points of Exxon’s history, starting with research in the late 1970s that began sounding alarm bells about what was then known as the greenhouse effect. One Exxon researcher told employees that “there is general scientific agreement that the most likely manner in which mankind is influencing the global climate is through carbon dioxide release from the burning of fossil fuels.”

ICN credits Exxon with working fruitfully with the scientific community for many years, before joining with the rest of the industry in mounting a campaign of skepticism and denial. From part III:

As the consensus grew within the scientific world, Exxon doubled down on the uncertainty. Its campaign to muddy research results placed the company outside the scientific mainstream.

The series is supported by timelines, source documents, and graphics. ExxonMobil’s response is to try to reframe the history: that there was always a lack of certainty, and that the company has always acted consistent with available knowledge. Nothing to see here!

But that clearly isn’t true – the evidence that the PR campaign started just as scientific groups organized their response and policymakers began getting serious about climate change is abundant. But not a single page on Exxon’s PR site (except for some user comments) even mentions the “Global Climate Coalition” and similar groups that were used to fight effective climate policy.

The investigative importance of the ICN series is undeniable, though I’m inclined to agree with one of the reviewers on Amazon, who notes a lack of editorial synthesis. Nonetheless, there are some elements of powerful storytelling, for example:

In 1981, 12-year-old Laura Shaw won her seventh-grade science fair at the Solomon Schechter Day School in Cranford, N.J. with a project on the greenhouse effect.

For her experiment, Laura used two souvenir miniatures of the Washington Monument, each with a thermometer attached to one side. She placed them in glass bowls and covered one with plastic wrap – her model of how a blanket of carbon dioxide traps the reflected heat of the sun and warms the Earth. When she turned a lamp on them, the thermometer in the plastic-covered bowl showed a higher temperature than the one in the uncovered bowl.

If Laura and her two younger siblings were unusually well-versed in the emerging science of the greenhouse effect, as global warming was known, it was because their father, Henry Shaw, had been busily tracking it for Exxon Corporation.

Email Newsletters

ICN offers multiple newsletters, including two curated collections of daily news from around the web:

- Today’s Climate covers energy and climate headlines;

- Clean Economy covers renewable energy.

Each newsletter item has a brief original summary, while the headlines are copied from the source. These digests are useful, but they aren’t as engagingly prioritized and curated as, e.g., the Marshall Project’s criminal justice newsletter (see our review). A single, more carefully compiled newsletter might be ultimately more successful.

Design, Tech and Licensing

The site is straightforward to navigate and works well on mobile devices. The list of “hot topics” (currently “Dakota Access Pipeline”, “Exxon Climate Investigation”, “Donald Trump”, etc.) is especially helpful, while the rest of the main page is a bit cluttered. Sections lead to in-depth investigations, infographics and documents.

There is no commenting system of any kind. There are, however, prominent instructions for submitting corrections and leaks, and a story correction I submitted via tweet was addressed quickly.

The site is under conventional copyright, granting content re-use on a case-by-case basis. Sassoon explained via email: “We rarely refuse [permission]. We’ve seen abuse of our content, otherwise. Also, we do partner with other media, and like to be able to grant exclusive access to our work.”

The Verdict

ICN is a very valuable, journalistic effort that sheds light on one of the most important topics of our era: the future habitability of our planet by humankind. The well-funded efforts to discredit this small organization speak to the impact that it has achieved through its award-winning investigations.

Indeed, the organization isn’t large enough yet to achieve the full breadth of coverage that the topic merits. One should therefore understand it to be a source of “watchdog” journalism, as opposed to a comprehensive view of climate/energy news (although the team’s news monitoring work helps with the latter).

The rating is 4 out of 5 stars: recommended reading. With a bit more editorial and design polish, more breadth/depth, and more consistency in organizational transparency, that rating may easily increase in future. ICN is now part of the Twitter list of quality nonprofit media.