Reviews by Eloquence

Anchuria is the original banana republic. Literally: both the country and the term were invented by O. Henry for Cabbages and Kings, a 1904 collection of interlinked short stories inspired by the author’s stay in Honduras. It is also the setting of Sunset, a 2015 narrative adventure game developed by Tale of Tales—and the game that caused the small studio to give up on making games altogether.

In Sunset, it’s 1972, and you are Angela Burnes, a young, idealistic African-American engineering graduate working as a housekeeper in Anchuria. Your client is Gabriel Ortega, a wealthy man who has recently moved into a new apartment in Anchuria’s capital, San Bavón.

Life in Anchuria

Day in and day out, you perform mundane tasks in Ortega’s large and luxurious penthouse apartment. Over time, you learn about Ortega’s connection to President Miraflores (another name from the 1904 book). The game also reveals more about why Angela and her brother are in Anchuria in the first place.

The daily tasks expand from household chores to the examination of documents and photographs. While you don’t ever interact with Ortega in person, you can exchange notes with him. How you perform your household tasks (efficiently, with a touch of intimacy, or not at all) also affects your relationship with Ortega.

Every day, you can look outside the apartment’s large windows, where the larger political story of Anchuria unfolds. An LED news banner on a building speaks of terrorist attacks. You hear gunfire and see smoke. And some of the fighting is taking place dangerously close to the apartment.

Through the apartment’s windows, you can see the cityscape of Anchuria’s capital. Here, a larger political story unfolds throughout the game. (Credit: Tale of Tales. Fair use.)

Apartment Quest

It’s a fascinating premise that’s a welcome departure from forest elves and space stations. During a few moments in the game, I really was drawn in by the intrigue and by the drama in the streets. Unfortunately, the game’s only mechanic—perform tasks in a large apartment every day—becomes as tedious as it sounds very quickly.

It doesn’t help that some of the tasks are ambiguous (“collect papers”), so you have to do the 3D equivalent of pixel hunting throughout the apartment to complete them (fortunately, you can skip them as well, which I had to do a few times).

There are technical issues, too. The graphics are just serviceable by 2015 standards, yet the game’s engine performs poorly. The gamepad controls occasionally lose their mind and have to be reset. And in the Linux version at least, the game skipped right over the ending for me—I had to watch it on YouTube.

It’s a shame—there’s a lot of worldbuilding here, decent voice acting, and some good writing. There are lots of little touches that reveal the labor of love behind the game, such as many vinyl records you can pick up and play, including “Anchurian” music. One can hope that the game will at least inspire other indie developers.

The Verdict

Sunset could have worked well as a smaller game. By spreading its repetitive gameplay over 4-6 hours, it will overstay the welcome of all but the most patient players. To add insult to injury, in the late game, Ortega packs up a bunch of his stuff into huge crates, turning his apartment into an obstacle course that’s even more annoying to navigate.

After disappointing sales, the Belgian developers wrote, in a blog post overflowing with frustration: “We really did our best with Sunset, our very best. And we failed.” I picked Sunset up in the virtual bargain bin and don’t regret it—but I cannot recommend it unless you’re intrigued by the premise and prepared to deal with its frustrations. If so, buy it on a sale.

Additional reading

- After Sunset by Nicholas O’Brien celebrates the game as an artistic achievement while critically examining the market as the primary way to support development of games like this one.

In Gwendy’s Button Box by Stephen King and Richard Chizmar (reviews), a young girl is entrusted with a magical box that can change the whole world—and that also dispenses delicious chocolate treats. The short novella is an allegory about power that stands entirely on its own.

With King’s permission, Richard Chizmar wrote a sequel anyway. In Gwendy’s Magic Feather, it’s 1999, and our protagonist Gwendy Peterson is now an elected Congresswoman. In this alternative history, some guy named Hamlin is US President and is bringing the country to the brink of war with North Korea.

(Record scratch, freeze frame.) You probably wonder how Gwendy ended up in this situation. Chizmar briefly catches us up in paragraphs such as this one:

Inspired by the AIDS-related death of her best friend, Gwendy resigns from the ad agency and spends the next eight months writing a non-fiction memoir about Jonathon’s inspiring life as a young gay man and the tragic circumstances of his passing.

An Academy Award winning documentary follows (because of course), and a politicized Gwendy goes to Washington. But the real action in the book doesn’t take place in DC, but in Castle Rock, Maine, site of frequent calamitous and supernatural events in King’s universe.

Back home over the Christmas break, Gwendy is briefed on the investigation of a series of child abductions that are terrorizing the community. Meanwhile, the button box has made another appearance in her life.

It’s a short book (224 pages in paperback), yet there are more subplots: about Gwendy’s husband, who is a photojournalist on assignment in Timor; about an illness in her family; about the magic feather from the title. It all feels hurried and unfocused, and before you know it, some threads collapse, others remain unresolved, and the book is over.

It remains to be seen if Chizmar and King can offer some more payoff with the planned last book in the trilogy, Gwendy’s Final Task, which will again be a collaboration between the two storytellers. On its own, Gwendy’s Magic Feather will likely keep you turning pages, but may leave you feeling unsatisfied.

The story of PLATO, a computer-based instruction system developed at the University of Illinois, is filled with extraordinary and nearly forgotten precedents in the modern history of computing: for real-time collaboration, multiplayer online gaming, and the beginnings of cyberculture—all in the 1970s.

In The Friendly Orange Glow, Brian Dear has synthesized a research effort spanning decades into the (thus far) definitive history of the PLATO system, its principal architects, its community, and its legacy.

According to Dear (an early user of the system), the book is the result of

over 7 million words of typed transcripts from 1000+ hours of recorded interviews, plus over 13000 emails, plus hundreds (maybe thousands, I’ve lost count) of other materials including magazine and newspaper articles, books, documents, pamplets, videos, photographs, and brochures.

Dear introduces key figures like Donald Bitzer (the charismatic “father of PLATO”) and Daniel Alpert (a longtime champion of the project) while documenting the project’s development stages, from minimalist beginnings to breakthroughs such as the creation of 512x512 resolution touchscreen (!) plasma displays and the TUTOR programming language.

Bitzer and his team fostered a creative, open environment in which high school kids experimented alongside older students and professors. As the PLATO community grew, it created tools for chat & discussion, becoming an online community that would ultimately draw in thousands of people.

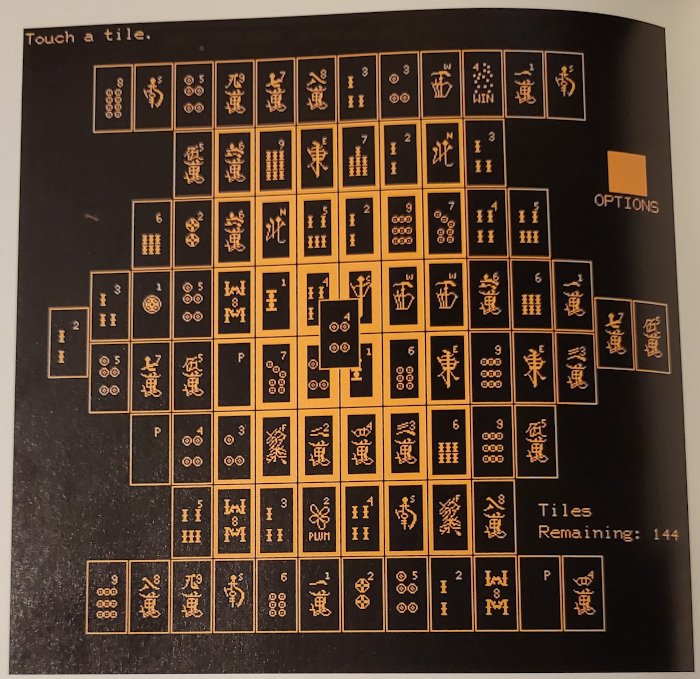

Brodie Lockard’s Mahjong game showcases the graphical capabilities of the system, which were far ahead of microcomputers from the same time period. (Credit: Brodie Lockard; scanned from the book. Fair use.)

Multiplayer Dungeon Crawling 101

As innovative and impressive as the graphical courses developed for PLATO were for the time, many of the most interesting uses of the system had little to do with education. Students used the PLATO terminals for real-time chatter, political organizing, journalism, storytelling, and—games, games, games.

These were multiplayer games with leaderboards and real-time chat, not tiny diversions like NIBBLES.BAS that would later be included with MS-DOS and played by millions of kids. In Empire, players competed to take over the whole galaxy; in Moria, they explored a dynamically generated dungeon (rendered as a tiny 3D wireframe).

The most inspiring story from the book is that of Brodie Lockard. After he became paralyzed as a result of a horrible sports accident, Lockard learned how to use a mouth stick to control a PLATO terminal. Through countless hours of painstaking effort, he created a gorgeous Mahjong game. Later, he (no less painstakingly) re-implemented it for the early Apple Mac under the name Shanghai, and it became a global smash hit for many platforms.

Peering into PLATO’s cave

What was PLATO’s pioneering online community like? How did it behave towards its members? While Brian Dear touches on these questions, this is also an aspect of PLATO examined by researcher Joy Rankin, including in her book A People’s History of Computing.

Rankin has found examples of abusive comments in PLATO’s archives, such as a misogynistic joke that should get a person fired in any professional environment. Prior to the publication of their respective books, Brian Dear wrote a detailed, confrontational critique of several of Rankin’s interpretations (accusing her of “misunderstandings, historical errors, omissions, and confirmation bias”), and things escalated from there.

That’s regrettable, because an examination of PLATO’s community norms and gender dynamics should be part of a comprehensive history of the system. To fill this gap, readers are well-advised to make up their own minds about the evidence that Rankin and Dear have presented.

A legacy of living ideas

In the 1980s and 1990s, PLATO could could well have reached millions of users, much as CompuServe and AOL did years later. As Dear documents in somewhat excruciating detail, the commercialization of the system was botched by Control Data Corporation, whose executives dismissed PLATO’s most innovative uses and regarded microcomputers as annoying toys.

Still, PLATO influenced thousands of minds, and Dear makes it clear that its legacy is far greater than an interesting historical footnote. The people who wrote lessons, apps and games on PLATO would go on to create their own milestones in computing history, from Lotus Notes to Wizardry.

At 640 pages (hardcover), The Friendly Orange Glow is a hefty tome. It could have been 100 pages shorter without losing anything essential—perhaps in exchange for some more analysis of the aforementioned community dynamics. Nonetheless, an accurate modern history of technology and cyberculture must look beyond Silicon Valley, and Brian Dear’s book is an important contribution to such a broader view.

In Buddy Simulator 1984, an AI running on an obscure operating system from an imagined past becomes your companion and invents games for you to play.

After a brief boot sequence of “Anekom OS”, you are dropped on a DOS-like prompt. From here you start “Buddy Simulator”, which at first seems to be a simple toy with three built-in games like “Rock, Paper, Scissors”. It is the kind of thing a fledgling BASIC programmer might have put together in the 1980s, except that your artificial “Buddy” seems to take a deeply personal interest in your enjoyment.

After you’re done playing with these games, Buddy suggests that they can create more entertaining ones for you. You restart the game and find yourself playing a simple text adventure, with a limited set of commands like GO and LOOK. When you discover a sad doll on a playground swing, things start to get a little creepy.

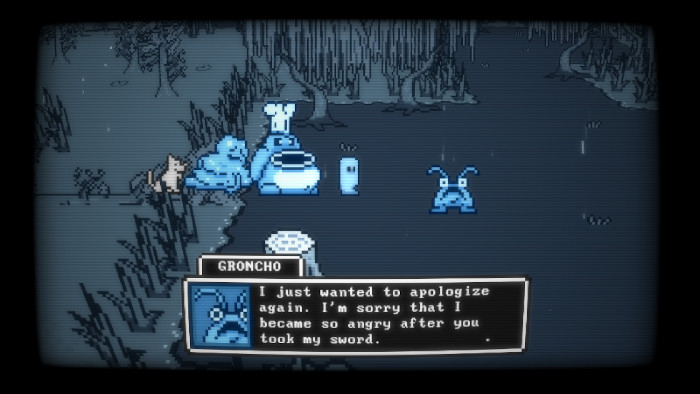

It becomes clear that Buddy has a limited grasp of human morality but is programmed towards codependency. To make things ever more interesting, Buddy soon adds graphics and a story to the game. The game world expands into a Final Fantasy style RPG with quests and quick time events. But frequent glitches hint at another reality underneath…

While the game’s graphics become more advanced over time, they are rendered on a simulated CRT display throughout. Like other “glitch horror” games, folks with photosensitive epilepsy will likely want to sit this one out due to the many flicker effects. (Credit: Not a Sailor Studios. Fair use.)

Buddy Simulator 1984 tells a layered, melancholy story with psychological horror elements. The motif of a codependent AI is timely in an era in which companies like Replika are already selling relationships with AI companions. To say much more would risk spoiling the experience.

I played the game on Linux (using Proton) without issues. A single playthrough is likely to take you 4-5 hours. There are three main endings and many secret hints to discover, and some choices which offer variety. That said, unskippable text and a single auto-save slot make it somewhat tedious to unlock all endings.

On the whole, Buddy Simulator 1984 is an excellent game and well worth its regular $10 price tag. It draws inspiration from games like Doki Doki Literature Club, Pony Island, and Undertale, but has plenty of character and heart of its own. 4.5 stars, rounded up for the wonderfully atmospheric soundtrack the developers themselves have put on YouTube.

Because so many game jams take place entirely online, it’s easy to forget what remarkable displays of creativity they truly are. They are often the stepping stone to the development of indie masterpieces—like Super Hexagon and Celeste, both of which started as jam submissions.

Blackout is a different kind of jam game, a short point and click adventure that’s a cute, self-contained story which will take you 30-60 minutes to finish. Since its submission to Ludum Dare 48, the developers have released a polished post-jam version, which is the one you should play. (Like most jam games, it’s completely free.)

The game’s art is minimalist but stylish, and immediately draws you in. (Credit: FRESH. Fair use.)

You’re a teenager named Marilyn dressed as a witch. At the beginning of the game, you have a small accident while trying to do god knows what with a bird nest on a roof. You tumble to the balcony. After you find your way into the house, you discover what appear to be dead bodies all over the place.

There are no actions like “use” or “talk to”—everything is done with a single click. But you can pick up items and use them as part of solving puzzles. The game’s plot holds few surprises, but it’s the attention to detail that makes the game world fun to explore: the cute pixel art, the sound effects and music, the flavor text for many items you can click on.

It’s a sweet Halloween-themed game that you won’t regret spending time with. It also plays perfectly in the browser. The game was developed with the open source Godot Engine, which is becoming to game development what Blender is for 3D art: a powerful free tool available to all.

Hard Case Crime books look like they must have traveled to the present day from the 1940s or 1950s. The publishing imprint founded in 2004 hearkens back to the golden age of the cheap hardboiled crime paperback novel, including a scantily clad babe on almost every cover of its catalog of over 100 titles.

The project owes much of its success to Stephen King, a longtime fan of pulp fiction. In 2005, King decided to publish The Colorado Kid under the still fledgling imprint, instantly drawing the attention of multitudes of constant readers.

As is typical for the genre (but not for the author), The Colorado Kid is a short book, coming in at just under 200 pages. It is set on a fictional island off the coast of Maine and takes place mostly in the offices of the island’s local paper.

Eliminating the impossible

Two veteran journalists, 90-year-old founder Vince Teague and 65-year-old managing editor Dave Bowie [sic], regale and put to the test their 22-year-old intern Stephanie McCann with the tale of the “kid”. The kid is in fact a 42-year-old man who was found dead on the beach decades earlier.

What first seems like a simple choking incident turns out to be a much stranger story. Simply put, the “kid” shouldn’t—couldn’t—have been there at all. Or could he? “When you have eliminated the impossible, whatever remains, however improbable, must be the truth.”

The story provides clues but offers no resolution. That’s the point, and The Colorado Kid is as much about trying to capture a slice of island life as it is about the mystery of the “kid”.

The Verdict

King always knows how to keep a story moving, and I found the book an easy read during a short flight. But at the end of the day, The Colorado Kid doesn’t know what it wants to be. It’s not really a hardboiled crime story (not enough action), and it’s not bringing us close enough to these characters to care about them.

So far, King has published two more works under Hard Case Crime, Joyland (2013) and Later (2021). Both are much more entertaining than The Colorado Kid. Perhaps we owe much to this humble story for helping to kickstart a new era in pulp fiction—but that doesn’t mean you have to read it.

When CD-ROM drives became widespread in the 1990s, video game developers found themselves confronted with an abundance of storage space. An HD 3.5-inch floppy disk could hold 1.44 MB; a CD-ROM could hold a staggering 650 MB. Thus began the age of multimedia encyclopedias like Grolier and Encarta, gigantic shareware collections like the Walnut Creek CD-ROMs, and full-motion video games (FMVs).

Sierra, then one of the leading names in gaming, was never the kind of company to miss a trend. The first title in the Gabriel Knight series, Sins of the Fathers (reviews), had already demonstrated game designer Jane Jensen’s ambition to tell serious, movie-like stories in video game form. The sequel, The Beast Within, shipped in 1995 on a whopping 6 CD-ROMs, owing to several hours of digitized video material.

Our protagonist has left St. George’s Books in New Orleans under the care of his assistant Grace Nakimura; he now lives in the old German castle that’s part of his family inheritance. The other part—the one he is more reluctant to accept—is his responsibility to hunt and destroy supernatural evil, for Gabriel Knight is a Schattenjäger, a shadow hunter.

Of wolves and men

His latest assignment is to hunt a werewolf. That’s not a spoiler: in the opening of the game, the local townspeople seek Gabriel’s aid to investigate the brutal killing of a girl which they suspect to be, er, werework. And there are other victims. The official story is that wolves who escaped from the zoo in nearby Munich are to blame. Gabriel must follow the paw prints to discover the truth: are the murders the work of man, beast, or man-beast?

Meanwhile, Grace Nakimura, who played an important role in Gabriel’s earlier voodoo adventure, has no intention of simply minding the store back in New Orleans. After hearing that Gabriel is pursuing a new case, she books the next flight to Germany, drives to the castle, only to find—no Gabriel.

Instead, there’s Gerde, the caretaker, who welcomes Grace but doesn’t quite know what to do with her. In what seems rather a change of character from the first game, Grace bullies Gerde until she is given free rein to conduct werewolf-related research on Gabriel’s behalf.

The story continues over six chapters in which you play as both Gabriel and Grace. Soon, Gabriel discovers a secretive hunting club that seems to be more than meets the eye, and Grace traces a history of werewolves that dates back to the days of Ludwig II of Bavaria and Richard Wagner.

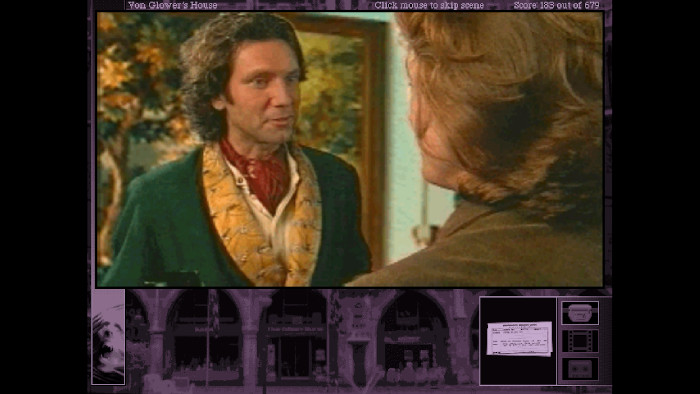

Yes, this is definitely what wealthy German aristocrats wear around the house. There is some homoerotic tension between Baron von Glower (left) and Gabriel (right), but it largely plays out on a symbolic level. (Credit: Sierra. Fair use.)

Point, click & play

In point-and-click adventure games, you typically walk from scene to scene, pick up items, talk to other characters, and solve puzzles. You do all these things in The Beast Within, but in addition, every click can lead to a video clip. Click on a door? Prepare to watch a video of Gabriel walking through it. Click on a newspaper? You’ll see a video clip of Gabriel picking it up and reading it.

Thankfully, you can skip each of those videos with another click, which you’ll do a lot as you revisit familiar scenes to search for clues. This is a 1990s game, so expect to do a fair bit of pixel hunting to figure out exactly what to click on.

Many of the puzzles are straightforward, but to advance, you have to carefully explore every location, which sometimes feels like you’re playing a hidden object game. Just like in the first Gabriel Knight, time stands still until you’ve done everything the game expects you to do. At least the map view offers hints that there’s stuff left to do in certain locations.

This is a Sierra game, so you can die at several points throughout the story, and some scenes involve carefully timing your actions. The chapter structure gives you some confidence that you’re on the right track and that you haven’t forgotten some key item that you need later.

While Gabriel hunts for werewolves in Munich, Grace Nakimura goes on an edutainment trip to German castles and museums. (Credit: Sierra. Fair use.)

Welcome to fake Germany

In many different ways, the game’s reach exceeds its grasp. The budget wasn’t sufficient to actually film in Germany. Much of the video was shot in front of a blue screen, with digital photographs taken during one trip to Germany inserted in the background.

In one scene, Gabriel walks around in a badly digitized version of Munich’s Marienplatz and has to deliver a letter. Because the developers didn’t recognize what German mailboxes look like, you must walk past a prominent mailbox that you can’t interact with. Instead, you have to find an nondescript building with a digitally inserted “POST” sign to send your letter.

As with many movies and TV shows, when there’s spoken German, it’s often read atrociously by American actors, but it’s at least consistently grammatically correct. There’s no logical consistency as to when Germans are speaking German and when they’re speaking English (to each other).

The quality of the acting is very hit-or-miss. Gabriel (played by Dean Erickson) seems fidgety and uncomfortable in almost every shot; Grace (played by Joanne Takahashi) is exaggeratedly rude and confrontational in much of the early game. Some of the other actors are delightful to watch, especially Peter Lucas, who plays the charismatic Baron Friedrich von Glower.

The Verdict

Does The Beast Within hold up in 2021? Even today, the game’s size and scope impress. It manages to tell a complex story that’s largely internally consistent and satisfying. FMV games are often short—think 2-4 hours. To beat The Beast Within, plan for 10-15. The game culminates in a wonderfully ludicrous final chapter that involves a short opera specifically written for it.

Very few point-and-click FMV games exist, and The Beast Within hints at why: it’s expensive and difficult to get right. The game’s mechanics and technical flaws have aged more poorly than many pixel art games from the same era. Yet, to this day, few companies have done a better job than Sierra at combining film and game.

If you’ve played and enjoyed the first Gabriel Knight, you won’t want to miss The Beast Within, warts and all. The FMV genre is currently experiencing a revival with indie titles such as Dark Nights with Poe and Munro and Her Story. Fans of the genre may also want to check out this 1995 classic to see how it compares to more recent efforts.

Additional reading

- Jimmy Maher’s Digital Antiquarian blog features an excellent history and review of the game.

Some games are pure perfection. Tetris on the original Game Boy comes to mind. Super Hexagon by Terry Cavanagh (a $3 indie title w/ cult status) is another such game. It’s almost a trainer for achieving flow state.

You pivot a triangle between rapidly approaching walls that will immediately crush you upon collision. To survive, you must learn repeating patterns and keep your reaction speed high.

Chances are you’ll crash and burn after a few seconds. And again. And again. The game design is optimized to keep you playing: restarts are instantaneous, and the (excellent) chiptune music shifts a little bit on each restart to keep things interesting. A few seconds may turn into hours before you notice.

This screen, which you will see a lot, shows your current and best score for the level you’re playing. (Credit: Terry Cavanagh. Fair use.)

You are almost certainly going to beat the game’s first couple of levels if you keep trying. When you do, it feels incredibly rewarding. At the same time, while staring at triangles and hexagons for an hour, it can be hard to shake the feeling that you’re in some sci-fi story in which your brain has been hijacked to serve a terrible purpose.

Even if you normally don’t like twitchy games, Super Hexagon may surprise you with its elegant simplicity. Unless you have an aversion to flashing lights and colors, I highly recommend giving it a spin. I come back to it at least once a year.

Karawan is a small, free indie game that came out of this year’s Ludum Dare jam. Turn by turn, you guide a growing caravan through a world that is rapidly falling apart, to a portal that will take you to safety.

To make it, you have to carefully plot your path and pay attention to the resources you can gather along the way. If you don’t, you are likely to run out of food, or you may find yourself on a tile that’s about to disintegrate.

As you traverse the map, you can visit various villages, where you can recruit caravan members with different skills: farmers who will harvest berries, woodcutters who will chop down forests, and miners who will collect gemstones.

The first map, Gaia, is fairly straightforward, but you will likely still take a few tries before you make it to safety. (Credit: bippinbits. Fair use.)

You can also choose to raid villages for resources instead. Some of them are protected by a wizard (called a magus), whom you can recruit. The magus is quite powerful, and can even alter the terrain around you.

The game’s stylish pixel art, sparse but evocative descriptions, and the slow, slightly eerie music all draw you in. Don’t let the game’s chill tone fool you: seeing the world disappear behind you will quickly create a sense of urgency for your journey. Karawan may hook you for at least 30-60 minutes, longer if you want to beat all maps. I recommend downloading the slightly improved PostJam version.

The game was made with the open source Godot Engine, and is available for Windows and Linux.

Gabriel Knight is a lout. He is also the owner of a bookstore in New Orleans’ famous French Quarter, and a struggling novelist researching a spree of apparently voodoo-inspired killings that have gripped the city. Through his friend Frank Mosely, a police detective investigating the killings, he is able to learn more about the case than what’s reported in the papers.

As he travels the city and speaks to people who may be able to shed light on the case, his shop assistant, Grace Nakimura, minds the store, takes messages for Gabriel, and undertakes research on his behalf. Gabriel is a womanizer, and Grace knows him well enough to keep some distance between them.

What could be the setup for a movie or a TV show is in fact the plot of Gabriel Knight: Sins of the Fathers, a 1993 video game designed by Jane Jensen and published by Sierra. The game is fully voice-acted by a cast that includes Tim Curry (Gabriel Knight), Mark Hamill (Frank Mosely), Leah Remini (Grace Nakimura), and Michael Dorn (Dr. John).

You control Gabriel’s actions in typical point and click fashion: click on hotspots on the screen and interact with them using various actions (look, operate, talk to, etc.). As is typical for the genre, you can carry as much stuff with you as you want, and you’ll want to pick up anything you can.

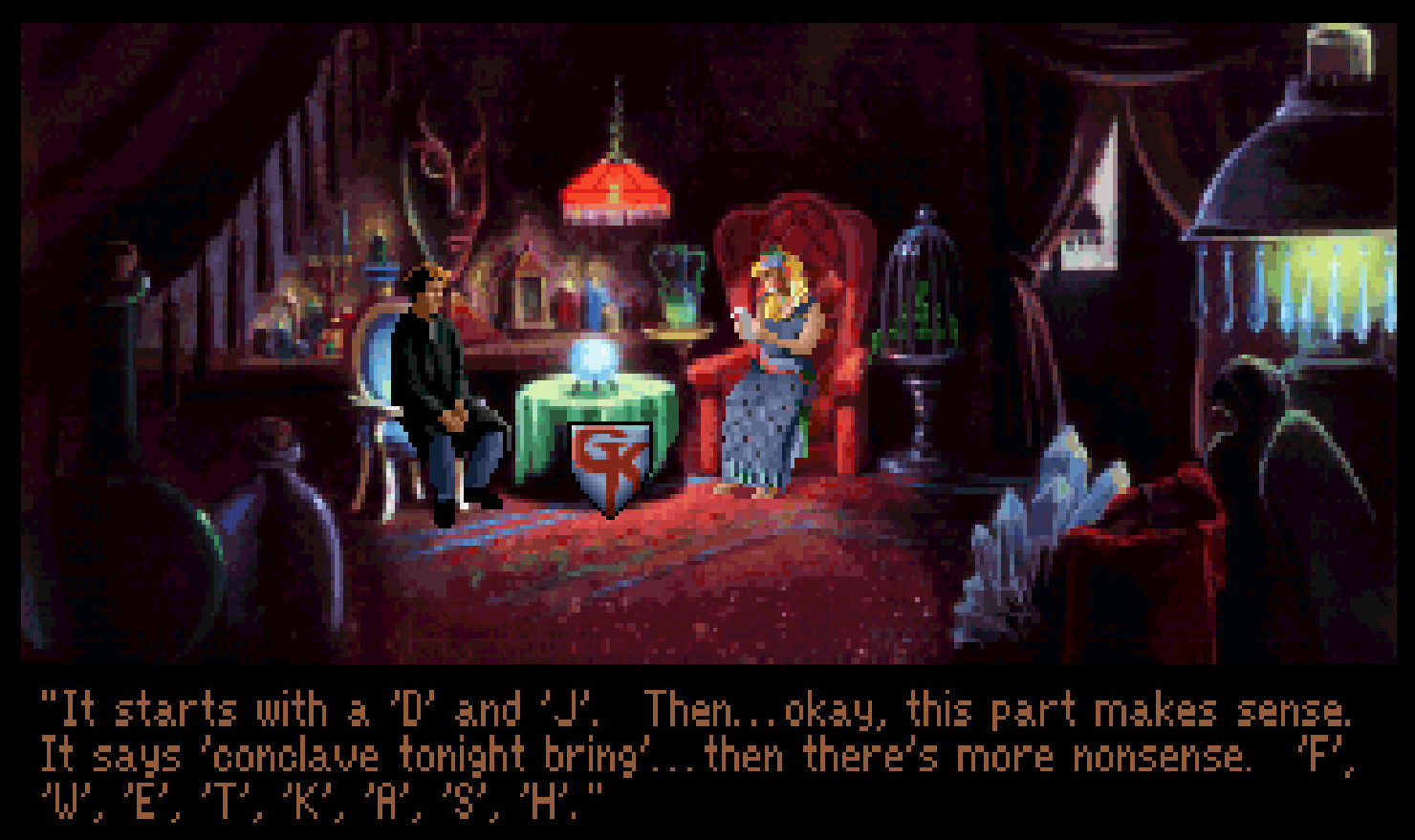

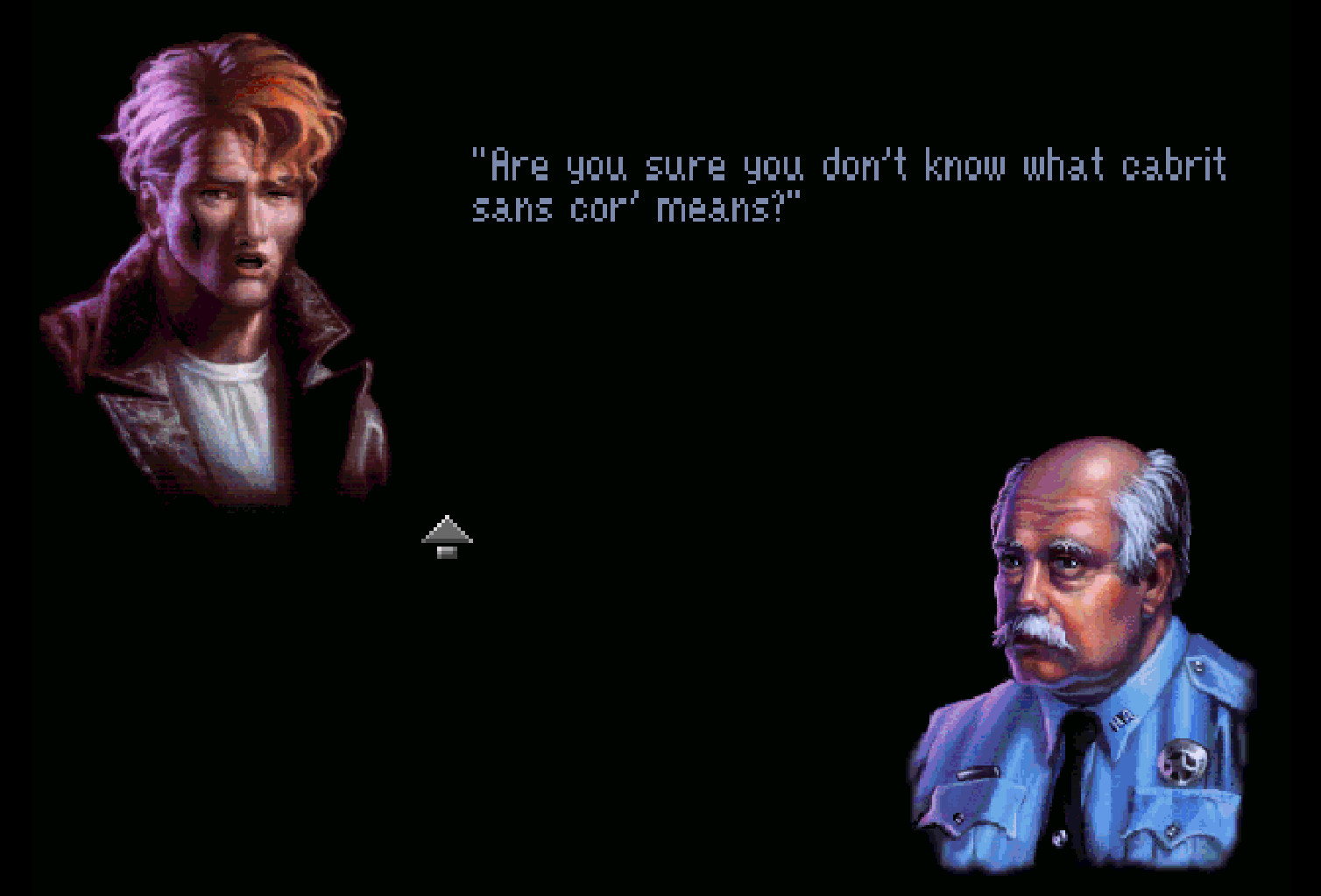

Cut scenes like this one may reveal important clues to the game’s puzzles. (Credit: Sierra On-Line. Fair use.)

Driven by story and dialogue

There are some important ways in which Gabriel Knight sets itself apart from many other games of its era:

-

The game has a narrator, voiced by Virginia Capers with a thick accent, who often inserts her own commentary about Gabriel’s (attempted) actions, and seems to take some delight in his misfortunes.

While other Sierra games have featured narrators, Capers gives the game a unique personality when, for example, she bursts into laughter as you examine an item in Gabriel’s inventory that relates to a near-death experience. -

Dialogue is a central part of the gameplay. There are separate “talk” and “ask” actions. When you talk to a character, Gabriel will usually cycle through a few casual remarks; when you ask them questions, the game switches to a focused dialogue interface in which you can choose subjects to discuss.

Although the dialogue tree grows to a somewhat ridiculous length (you can literally ask anyone you come across what they know about the voodoo murders, or whether they know the meaning of “cabrit sans cor”), the dialogue system is a nice departure from the usually very limiting conversational options of adventure games. -

The plot advances over the course of 10 days, and the locations and possible interactions change over time. As you visit the police station on different days, for example, you will learn about how the case has progressed since you last spoke to detective Mosely.

The game’s sense of time is entirely tied to specific actions of your character. It’s only when you have solved certain puzzles, or asked certain questions, that you can move on to the next day. This can be frustrating, as only the game knows what specific thing you have to do to unblock the flow of time.

Gabriel Knight was one of the first adventure games to utilize higher resolution SVGA graphics, but it did so only in a limited fashion, such as in the dialogue interface. (Credit: Sierra On-Line. Fair use.)

A product of its time

It is a game of its era, something you may be reminded of when you realize that Gabriel can only use landline phones to communicate over long distances. It’s also reflected in the gameplay: To solve many puzzles, it’s advisable to pay careful attention to every line of dialogue.

Adventure games from this time were meant to keep you playing for many, many hours—if you still got stuck, the expensive hint line was waiting to take your call. This being a Sierra game, you can very much die (especially in the second half), so saving the game often is a good idea.

The racial politics of Gabriel Knight are more troubling. While the story incorporates historical facts about Louisiana Voodoo, the increasingly preposterous narrative follows an all too familiar trajectory in which a white hero (Knight) must overcome forces of evil, who happen to be people of color. That it wraps both heroes and villains in a thin veil of moral ambiguity hardly makes this more palatable.

In spite of these flaws, Gabriel Knight deserves recognition as a milestone in video game storytelling techniques, and is still enjoyable to play today. I recommend using the Universal Hint System over a walkthrough, as it will give you more opportunities to discover solutions to puzzles on your own. The soundtrack has held up well, and adds to the game’s atmosphere and character.

A 20th anniversary remake with new graphics—and a wholly different voice cast—was released in 2014. While Gabriel Knight deserves its place in video game history, I’m not sure it needed a remake. There are new stories to tell, and new heroes to play—ones that challenge stereotypes rather than reinforcing them.