Latest reviews

Imagine you find an alien spacecraft crashed in your backyard. A door has cracked open. You carefully step inside. You discover a world beyond your comprehension. Objects appear before your eyes, only to disappear into thin air. Lights flash in colors you cannot see. It will take humanity’s brightest minds years—decades—to make sense of it all.

Biology is a science attempting to comprehend something no less strange or bizarre: the evolved nano-machinery that constitutes what we call life. We give our discoveries opaque names. Ribosomes. The Golgi apparatus. Neutrophils. When those get too long, we abbreviate. MHC class I and II. ACE2. CD24.

Here lies a wondrous and endlessly fascinating world. Understanding it better could enrich our lives and help immunize us against dangerous pseudoscience. If only we were better at describing this complex, seemingly impenetrable universe inside our own bodies!

Philipp Dettmer is no stranger to making the complex comprehensible. He founded a YouTube channel called Kurzgesagt (“in a nutshell”), which publishes lovingly crafted videos on subjects like wormholes, geoengineering, and brain-eating amoebas. Thanks to brilliant animation, epic music and a dark sense of humor, every video is a treat.

Immune: A Journey into the Mysterious System That Keeps You Alive is Dettmer’s first attempt to bring Kurzgesagt’s trademark educational approach into book form. On 341 pages, Immune sheds light on the incredibly complex macromolecular machinery that protects us against bacteria, viruses, and even snake venom and parasitic worms.

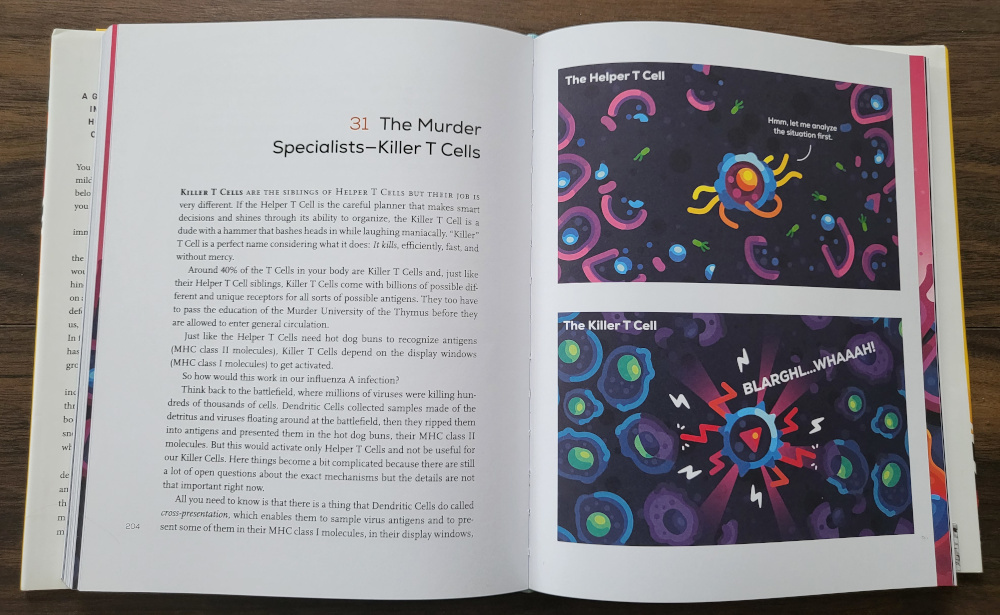

Most illustrations are more understated than the ones shown here, but this is not a book that shies away from depicting a Kiler T Cell saying “BLARGHL”. (Credit: Philipp Dettmer / Random House. Fair use.)

This is not a textbook. Nor is it the kind of pop science writing that tries to make science accessible by giving you lots of biographical detail about scientists. It’s strictly focused on the actual mechanics of the immune system, but written in a style that’s entirely Dettmer’s own. To give a small sample:

The Neutrophil is a bit of a simpler fellow. It exists to fight and to die for the collective. It is the crazy suicidal Spartan warrior of the immune system. Or if you want to stay in the animal kingdom, a chimp on coke with a bad temper and a machine gun. [p. 59]

Of course, Dettmer frequently reminds us that the immune system is not, in fact, sentient or intentional. It’s just that these kinds of analogies are too darn useful to refrain from using them. So, Dettmer talks about hot dog buns, display windows, and desert kingdoms as he helps us navigate the complex nano-scale landscape inside our bodies.

But analogies only go so far, and the book uses biological terms and plenty of straightforward illustrations. At the same time, Dettmer will often (a bit too often) emphasize that he’s still simplifying things greatly. The book is littered with entertaining footnotes that expand on the text.

Cells with two-factor authentication

The immune systems of humans and other animals don’t just have to kill invaders. They have to adapt to viruses they’ve never encountered before, detect cells that have been hijacked, calm down when a threat has been eliminated. To make matters worse, the attackers evolve rapidly!

Immune responses involve the innate immune system, a sort of standing army, and the adaptive immune system, which crafts specialized responses for novel threats. Together, they self-organize into a complex dance. Isolate the threat. Sample data. Ramp up immune responses. Kill or neutralize invaders. Detect cells that behave suspiciously. Mess with virus production.

Perhaps most fascinating is our bodies’ ability to learn and remember—to acquire immunity. At its heart is what Dettmer calls the largest library in the universe: T-cells. Wikipedia has a more understated but no less awe-inspiring description:

Each mature T cell will ultimately contain a unique T-cell receptor that reacts to a random pattern, allowing the immune system to recognize many different types of pathogens. This process is essential in developing immunity to threats that the immune system has not encountered before, since due to random variation there will always be at least one TCR to match any new pathogen.

It takes time for our adaptive immune system to find the perfect match for any given threat. But once it has done so, it switches into a kind of mass-production mode, to produce vast numbers of antibodies tailored to a specific enemy.

To avoid misfiring, cells perform complex verification dances. T-cells undergo a selection process that weeds out ones that might attack the body. And they must be matched with another cell type (B-cells) that have been activated by the same threat. Dettmer calls it a kind of two-factor authentication.

As someone working a lot with technology, I found these comparisons illuminating. Understanding the sophisticated evolved security responses of our bodies may very well inspire us to develop better ways to deal with novel threats of a more digital variety.

Knowledge as immunity

Our brain, in a way, is part of our immune response. Our decisions on what to eat and drink, what to do with our free time, how to prevent and how to treat illness—they profoundly influence our ability to stay healthy, and to get better. When we believe things that are patently false, it can literally kill us.

Dettmer spends the final sections of his book trying to convey how understanding our immune system can help us make better decisions.

He explains the remarkable accomplishment of vaccination as a way to train the body without hurting it: like a dojo where you learn to fight with weapons made of foam and paper. In contrast, parents who opt their kids out of vaccines are sending them to a “Nature Dojo”:

The philosophy of the head trainer is that kids should train with real weapons, real knives and swords, so they are better prepared for the real dangers of the world. After all, it is more natural and real life just is dangerous. From time to time, a student will get a deep cut and require stitches. And yeah, OK, there may be a lost eye and sometimes a kid may die. But it is the natural way! [p. 240]

He asks us to question dubious claims about “boosting your immunity”—reminding us of the immune system’s mind-boggling complexity and interplay of countless parts, where any actually effective intervention can have disastrous effects. He tells us to exercise (it’s obligatory in any book of this kind), and describes how stress can knock our immune system out of balance.

These final sections of the book sometimes get a bit rambling. The most muddled chapter discusses the popular misconception that hygiene has weakened our immunity against disease. Dettmer argues for preserving good hygiene while also embracing the role of nature and dirt in our lives—a reasonable argument that’s unfortunately not very coherently made.

The Verdict

With Immune, Dettmer has managed something very difficult: to write a long book almost entirely about the mind-boggling macromolecular and cellular machinery inside our bodies, without fluff, that’s entertaining to read. I would love to read similar books about subjects like epigenetics, metabolic pathways, or neurobiology!

Science books often have an incongruous approach to visual explanation. Immune is the rare exception—while it does not have as many illustrations as some readers might expect from the Kurzgesagt founder, what’s here supports the text perfectly in a consistent, pleasing style.

The latter parts of the book would have benefited from a bit more rigorous editing, but I’m glad that Dettmer’s funny and casual voice hasn’t been whittled down to science-journalism-speak.

All in all, I cannot recommend the book highly enough, and would give it a full 5 stars.

Auch wenn die Flut der Burgerläden schon länger vorbei ist öffnet doch noch ab und zu ein neuer Laden. Und diesmal hat er es in sich. Die Burger hier gehören meiner Meinung nach zu den besten, die es in Hannover gibt. Eine sehr kleine Speisekarte lasst erahnen, das es hier hohe Kompetenz in Sachen Burger und Co. geben kann. Und die Vermutung bestätigt sich. Was auf meinen Fotos (es liegt am Fotografen nicht am Burger) sehr unscheinbar aussieht ist ein sehr leckerer Burger. Frische Zutaten, reichlich verwendet und vor den Augen zubereitet. Dazu leckere, grob geschnittene Pommes und ein Getränk nach Wahl - fertig ist das Menü.

Burger und Pommes im Black Stork (Eigenes Werk. Lizenz: CC-BY-SA.)

Einzig das Ambiente vor Ort ist ein wenig ungewohnt. Der halb-offene Gastraum, wenn es denn so bezeichnet werden kann, an einer der Hauptverkehrsstraßen Hannovers ist gewöhnungsbedürftig. Im Sommer lässt es sich gut aushalten im Winter bleibt wohl nur die Mitnahme.

Hotline Miami 2 is easily one of the most remarkable instances of creators trolling their own fan base. This game is notorious for not living up to the expectations set by its predecessor. Yet, I don’t believe that this game is a failure of game creation but instead has been deliberately constructed to be the way it is. To understand why we have to look at what came before HM2.

Context

Hotline Miami is a hugely celebrated action game from 2012. It’s a simple and self-contained game. Split into several levels, you play as an on-demand hitman who goes to the places left on his answering machine and commits a massacre. These killing sprees make up the core gameplay loop. From a top-down view you move through the levels and kill dozens of people to an aggressive electronic soundtrack—beating them, slashing them, shooting them. The violence is visceral, blood goes everywhere, and feedback is immediate. It’s addicting.

However, when you’ve killed everyone, the music stops abruptly, and the game has you walking back through the level to your car—walking through the pools of blood and corpses you created. In this simple way, the game traps the player in addictive violence but then suddenly pauses and asks you to reflect on what you just did. The commentary on violent action games is obvious. And with, at the time, massively popular shooter series like Call of Duty and Battlefield loving to employ the trope of the Russian villain, the fact that the people you are killing are part of a Russian gang is probably not a coincidence. And I have to admit that killing people in this game is a tonne of fun. Hotline Miami triumphs in its simplicity.

It is then very unfortunate, that this game acquired a fandom that absolutely loved the violence and obsessed over the game’s obscure plot while closing their eyes to the game’s actual message. This is the group of people that Hotline Miami 2 seeks to troll.

Sequel

Hotline Miami 2 is a sequel for the fans of the original game in the bluntest form. People liked the combat? We need bigger levels, more violence, and more play styles! People loved the obscure story? Let’s give them more characters, elaborate backstories for those from the original, and a non-linearly told story that’s gonna take some real puzzle-solving to crack! It’s designed to deliver the fans of the original an overdose of the same.

Explaining sequels like this as the result of lacking creativity or as a cynical cash grab might be tempting, but it’s just not the case here. The creators proved their creativity and game design abilities with the original Hotline Miami. And on top of that, the creative leads, Jonathan Söderström and Dennis Wedin didn’t change between the two projects. And lastly, there is significantly more effort put into this game than the predecessor, which is clear to see. It seems very unlikely then that this is just a way of cashing in for the devs.

The elimination of these possibilities and looking at the game’s contents make me believe it is trolling—an artistic statement on their relationship with their fandom.

Story

Hotline Miami 2’s story is completely incomprehensible in the way it is told. And on top of that, once you partially decipher what is going on, the story is plainly ridiculous.

The game’s overall presentation isn’t very helpful in making the player understand what is going on. The whole experience is styled after movies. The game is split into “acts”, which are subdivided into “scenes”, which you select from a menu of VHS tapes. The multiple timelines in the narrative are jumped between by, of course, rewinding and fast-forwarding the tape. And to really mess with you within the game’s narrative, there is an actual movie being filmed. You act out some of its scenes, which are often indistinguishable from things that actually happen within the game world.

But somehow, it gets even more convoluted once the game introduces its backstory in act three. Apparently, the USA and USSR fought a war against each other on Hawaii. The conflict was brought to an end with a nuclear first strike by the Soviets. And this is why Russians are hated so much in this world. That’s certainly one way of addressing that question. If that sounds ridiculous to you, it should! It certainly does to me. It’s the point where you should realise that the creators are messing with you.

I would usually not feel comfortable just blankly calling an entire game trolling like this. It would be bad for criticism if just everything that is contradictory or seems ridiculous could be written off as mere trolling. So how is this game different?

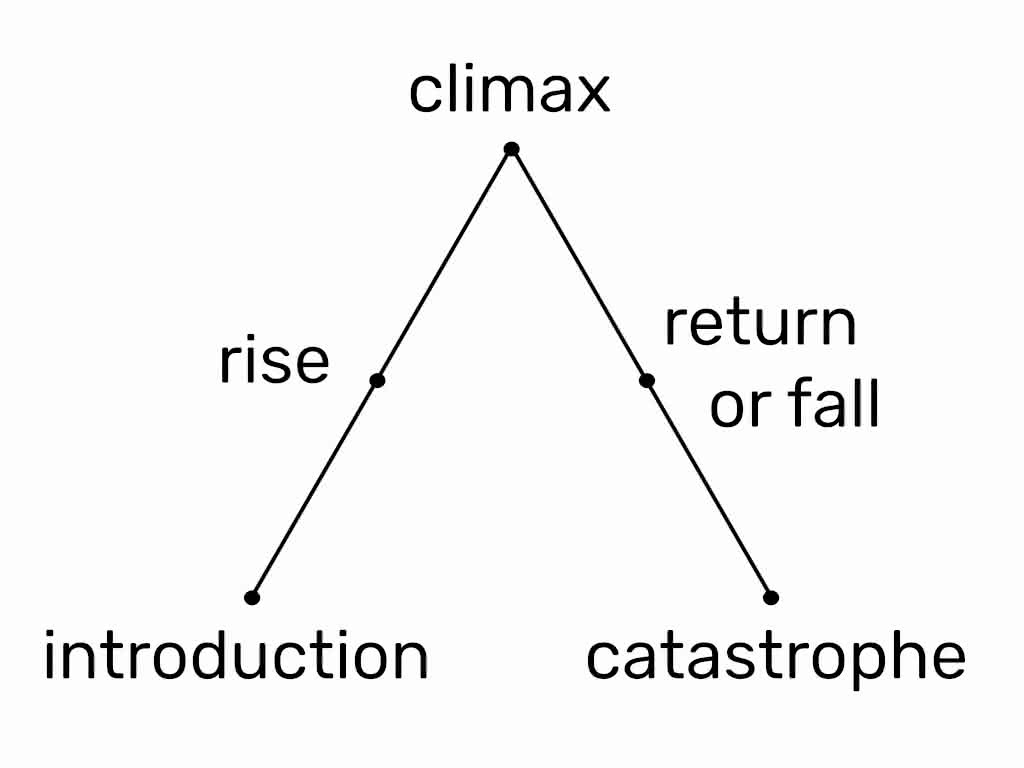

Besides the ridiculousness of the setting, and specific story moments that attempt a critical commentary on Hotline Miami’s fandom, the creators themselves don’t seem to have much respect for their own work on this game. The most obvious point would be how, at the end, the entire world is destroyed. Everything was told and set up for nothing, it appears. But there is an even clearer indicator. The game’s acts in chronological order are called: Exposition, Rising, Climax, Falling, Intermission and Catastrophe. Except for Intermission, these are exactly the generic names for the acts in the five-act structure of a drama. In fact, it’s so generic, here is an illustration of this structure I found on Wikipedia:

(Credit: SinjoroFoster. Public domain.)

While, clearly, a lot of writing effort went into this game, it’s not presented with a lot of heart. Combined with story moments that seemingly only exist to frustrate and confuse those that actually want to engage with the story, I think the case for this game being trolling is very straightforward. However, some moments do make sense if we understand them as commentary on the trolled audience. This goes for both the people that uncritically enjoyed the original‘s violence and those that obsessed over lore so much they missed the game’s actual point.

Hotline Miami 2 features a long list of characters that you play as. A lot, if not all, of these characters, are a meta-commentary on the game’s fandom. It highlights different nasty elements of that group.

The most obvious meta-commentary lies with a group of people that took inspiration from the player character in the original Hotline Miami for their streaks of mass murder. Like him, they wear different animal masks, but here they do all the time, unlike in HM, where they were only put on directly before a massacre. And just in case you didn’t get it, the game refers to this group as “The Fans” in its Achievements.

The Fans, unsurprisingly, kill for fun. Their final killing spree happens at the end of act three. Here you play as each one wiping out a floor of the building while an aggressive house track plays in the background. This is where all the people who The Fans represent get what they want. Except, at the end of the level, they all unceremoniously die. While the original game ends with some moral ambiguity, as the main character exacts his revenge on the mafia and triumphantly lights a cigarette, there is no justification or glory here.

Another character that loves the violence he’s enacting is a literal neo-Nazi. With the original‘s hints of ultra-nationalism (if you refuse to engage with metaphor), it’s not surprising that it appealed to a certain audience. You’re introduced to him as he shaves his head in the bathroom, and the moment you go into his living room, you immediately notice the flag of the Confederacy that is lying on his sofa like a blanket. After you are done carrying out his hateful killing, he tries to get a tattoo to celebrate the occasion but fails because he didn’t schedule an appointment. Here the creators are telling their Nazi fans to piss off, by showing them someone they can identify with and having him be a sad and pathetic loser.

Meta-commentary of the game extends beyond just commenting on the killing, however. Hotline Miami 2 starts out with a scene of sexual assault, where a murdering creep goes after a woman he thinks is his girlfriend. Initially, this looks like senseless provocation, but there’s more to it. You see, this scene is part of a film being filmed within the game’s narrative, which was inspired by the happenings of Hotline Miami. The actress, playing the victim in this scene, has a strong resemblance with a woman the main character in HM saves from the mafia. Actually, there is no clear indication that he is saving her. It might just as well have been a kidnapping. Either way, the woman lives with the main character from there on out. It’s not hard to imagine that this decision wasn’t entirely enthusiastic, or even a choice at all, considering the main character is a serial killer.

The movie plot in HM2 is a commentary on how not a lot of people got that you weren’t exactly a knight in shining armour in the original game. In a later scene, the creep is arrested because the woman reported him to the police. In the following level, you murder your way through the police station to where she is being interviewed. On entering the room, she shoots you and screams: “I am not your fucking girlfriend!” It’s clear what is being said here. And, again, just in case you didn’t get it, in the first level, where you play as one of the Fans, you are tasked with bringing the sister of another Fan home from a gang. You do what you do best—murder your way through to her—but she doesn’t want to go with you. You just murdered all her friends. Distressed and with a gun in her hands, she tells you to leave her and go. If you don’t listen and get closer, she shoots you, and you have to do the floor all over again. You get punished for not having learned your lesson.

Finally, the game’s story is a massive middle finger to those that obsessed over the original game’s lore while disregarding any of the game’s use of metaphor and allegory. This goes beyond the back story about the hot war between the USA and USSR being totally ridiculous. While the game gives these people a hugely convoluted story to unravel, it is all for nothing in the end. The game finishes in an outright nuclear war between the superpowers, using their capacity for mutually assured destruction to reduce the game world to ash.

Over the credits, you watch as every character that was introduced in the series (and is still alive) dying in a nuclear blast—one after the other. Did you have fun putting all the puzzle pieces together? Well, it’s gone now.

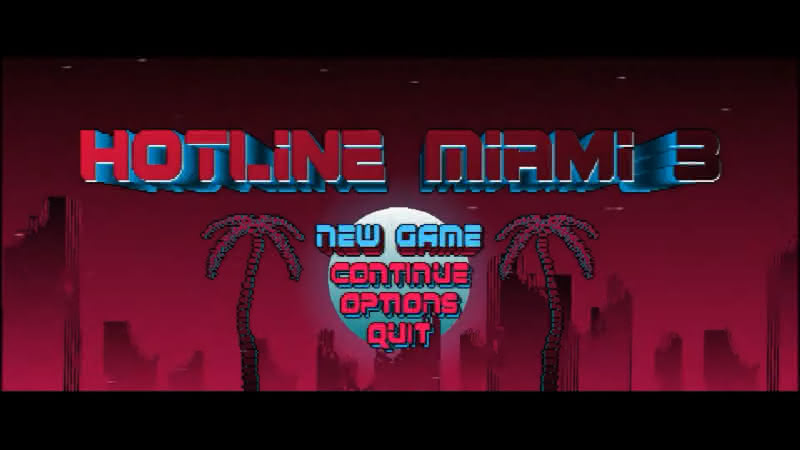

The final image you see of the game is the fictional start screen of “Hotline Miami 3”. In the background, you can see the ruins of the Floridian city. Of course, there is no narrative comeback from an ending like this. It’s not supposed to be an exciting teaser for another instalment in the Hotline Miami series. Instead, what it is doing is asking a question. You’ve just played through the sequel to Hotline Miami. How does the idea of another sequel make you feel?

(Credit: Dennaton Games. Fair use.)

There is a mean-spiritedness to this all. The game uses metaphor and allegory to make fun of and comment on the people who didn’t get that about the original. Pulling the story into the ridiculous and referencing characters from the original isn’t going to make them realise anything—it will all just seem like an even greater puzzle to unravel. While those who get it laugh at them, they do in-depth theory crafting for a game that showed them the finger, but, of course, they didn’t recognise it as such. And looking at the wiki articles and lore videos made for this game, it seems like that’s exactly what happened. Hotline Miami 2 could have tried to communicate how many got the original wrong but instead reads much more like the self-indulgent product of pure spite.

Gameplay

The gameplay in this game is not all that interesting because, except for some superficial additions, it is largely unaltered from the original. The music still stops abruptly after you are finished killing everyone. It’s still the same trial and error per level. You step-by-step uncover the best strategy for getting through it consistently with the twist that the enemies have slightly different weapons on every attempt, so you always have to improvise somewhat.

While the story is fully developed with a clear through-line of what it is doing, the gameplay makes Hotline Miami 2 feel a lot more like the misguided sequel that many people think it is. The game now features a wide cast of characters—each with their own unique traits. And further, new enemy types. But what really sticks out is the difficulty.

The game is immediately more difficult than its predecessor. While the first level in Hotline Miami featured only goons with melee weapons to get you accustomed to how the game plays in a manageable way, in Hotline Miami 2, the first enemy in the first proper level has a gun. And not just the one. There are many more of them with wide-open spaces and corridors for you to get shot from off-screen. The difficulty escalates more quickly too. In level three, you can already not trust walls and corners anymore because there are windows everywhere for you to get shot through.

The primary factor in Hotline Miami 2’s higher difficulty are the much larger levels. Because as there are more things, more things vary and can go wrong. Beyond that, the levels are so big that enemies triggered by a gunshot can take up to 15-20 seconds to get to you from areas of the floor you weren’t even looking at, catching you off guard.

But ultimately, this is tame in comparison to the story. It’s a somewhat more difficult and frustrating version of the original with some easy additions that one would expect from a sequel. The ridiculous tones of the story really don’t shine through here. The gameplay would have been the prime place to further the meta-commentary already present. But for whatever reason, this aspect of Hotline Miami stays relatively untouched. The core gameplay sections just being more frustrating is a huge missed opportunity. Despite being harder, it’s nothing you couldn’t get accustomed to. With enough trial and error, you will be able to triumph over this game’s difficulty. And that’s the problem: the gameplay does not challange this way of engagement. It could have been a great way to complement the messaging of the story with the core component of Hotline Miami, the violence. But instead, it settles for, arguably, giving the fans it set out to troll precisely what they wanted.

Conclusion

Hotline Miami 2 is a very fascinating game. The trolling aspects make for intriguing creator-fandom dynamics, but the game being unwilling to touch its own gameplay for that purpose undercuts it significantly. The primary interactive component of HM2 being a more-frustrating-but-nothing-more experience is very disappointing.

The game’s trolling has some great isolated high points, but, in my opinion, the game didn’t go nearly far enough.

5/10

This is an excellent narrated documentary about 4 ex-soldiers who have fought in the Angolan Civil War in the 80ies on different sides and come together to reflect about that traumatic time.

“There’s no son of any politician or leader that is fighting in war.”

I have to say that I am normally not very interested in documentaries. However, this one is hooking and at least very much completes fictional war movies.

KobraVario 25,4, produite par ErgoTec, est une potence à plongeur, angle ajustable et permet le maintien du cintre à l’aide de trois vis. Bien que destinée à un public varié, elle ne conviendra probablement pas à un usage plus musclé (2,7 W.kg⁻¹ dans mon cas). Suite à un remplacement par un vélociste, encore, ce dernier m’a vendu et installé cette potence sans tenir compte de mon profil d’utilisation. Après quelques mois d’utilisation au quotidien et plus de 5 ans plus tard, ce manque de considération se fait sentir. Sur la dizaine de vélos que j’ai pu avoir, c’est la première potence de ce genre que j’ai pu essayer et sûrement la dernière.

Potence plongeur

Aucun soucis particulier de ce côté, la tige est proposée à deux diamètres courants de 22,2 mm et 25,4 mm. Destinée à un remplacement sur un cadre Orbea Kronos3 de 1996, il fallait effectivement une potence à plongeur, même si l’apparence des ahead-set me séduit aujourd’hui, leur usage sur des cadres plus anciens requiert des adaptateurs que je n’avais pas sous la main et que je n’étais pas prêt à attendre de recevoir à l’époque.

Maintien du cintre

À la manière des ahead-set, le cintre est maintenue par une plaque serrée par trois vis. Sûrement moins solide que les modèles à quatre vis, je n’ai pas eu de problème particulier jusqu’alors avec ce modèle, le guidon est bien fixé et ne bouge pas. De façon intéressante, sur la page du produit est soulignée cette partie comme pouvant accueillir différents accessoires. À défaut de notices de montage et d’illustration, j’ai du mal à voir comment cela se goupillerait…

Angle ajustable

Atout à l’achat ou pour la vente, cette potence peut prendre différents angles pour s’adapter à différentes personnes. Le détail principal de ce produit. L’angle de la potence est ajustable selon un pas de 10° sur une gamme de -10° à 50°, bien qu’à priori rien ne vous empêche de retourner la potence sur la tige et doubler le nombre d’angles possibles. Bien qu’intéressant en théorie, peu de personnes en auront utilité au quotidien et j’ai des doutes quand aux conséquences que cela aurait sur la tension des câbles des freins et dérailleurs. Mon groupe Shimano RSX est particulièrement pointilleux sur les changements de vitesse.

Cet atout constitue également à mon avis la faiblesse majeure du produit en ajoutant une articulation, source de problèmes, supplémentaire. Probablement correct avec un cintre moustache en usage utilitaire, forcer un peu sur le guidon suffit à faire apparaître les problèmes. Au bout de quelques semaines d’usage, un jeu s’était développé au niveau de l’articulation et me suis jusqu’à présent. Fini la discrétion du vélo, bonjour les grincements. À partir du moment où je saisi le guidon jusqu’à la fin du trajet, chaque pression sur le guidon fait intervenir ce jeu qui provoque des grincements et un « mou » très désagréable dans la conduite. Seule, la vis à cale de serrage a bien du mal à supporter les forces exercées sur le guidon et la resserrer n’y change rien en plus de risquer d’endommager l’ensemble. Pas besoin de ça pour aller faire un tour chez le dentiste.

La potence KobraVario est un bon produit dont la première ligne du cahier des charges devait être « Grand public ». À vouloir toucher un public trop large, des inconvénients apparaissent clairement à l’usage. En l’occurrence et pour un usage plutôt sportif, je rappelle encore une fois que mon usage est loin de l’extrême du spectre en soi, l’articulation d’ajuster l’angle est un défaut de conception, pire encore qu’un gadget. Plutôt qu’un atout au quotidien, pouvoir ajuster l’angle de la potence est probablement plus utile au néophyte qui veut tester différentes position sur son vélo et trouver celle qui lui convient le mieux. Peut-être ainsi ce produit serait avant tout utile dans le cadre d’études posturales ? Pour autant, il m’est impossible d’accorder une mauvaise note à ce produit qui, bien que ne satisfaisant pas mes besoins, résulte plus d’une erreur de la part du vélociste (et de moi-même) que d’un problème structurel. Le fabricant lui même range cette potence dans la catégorie « Safety level » 2/6, juste un niveau au dessus des critères pour un vélo enfant.

Suite à des dégâts sur mon vélo, je me suis rendu dans cette boutique qui était à la fois plus proche de mon domicile que le centre-ville ainsi que du commissariat où j’ai du déposer plainte. Malgré mes compétences, je n’avais pas forcément le temps ni les outils à disposition pour faire le travail moi-même et ai préféré confier le travail à un professionnel. Erreur qui ne se reproduira pas.

Première visite : prise en charge

À ma première visite, j’ai été accueilli par une personne qui n’avait aucune idée des tarifs ou d’expérience dans la mécanique vélo malgré qu’elle soit en charge de la boutique en l’absence du patron. J’ai tout de même confié mon vélo et ai demandé a être recontacté pour le devis une fois les contrôles effectués.

Deuxième visite : devis

J’ai été rappelé le lendemain pour le devis. Annoncé à 150 €, mes deux jantes étaient à remplacer. À défaut de me l’envoyer par mail, j’ai également du me rendre sur place pour obtenir le-dit devis qui s’est révélé être un bout de papier griffonné, avec le tampon du commerce. Sur place, on me donne une estimation du temps de réparation à 1 h.

Troisième visite : demande de réparation

La troisième visite fût pour valider le devis et lancer les réparations. Après échanges avec mon assurance, j’ai finalement pu donner le feu vert pour les réparations. Le premier obstacle étant qu’il n’y a aucun moyen de contacter la boutique à distance, pas de téléphone ni d’adresse mail. J’ai bien essayé de rappeler au numéro utilisé pour me communiquer le montant du devis, et suis tombé sur la personne qui m’avait accueilli le premier jour, qui m’a indiqué ne plus y travailler et confirmé l’absence de moyen de contact. Je me suis rendu pour la troisième fois en boutique avec pour idée de pouvoir faire des courses en attendant. On m’annonce alors de devoir repasser le lendemain. Soit, démonter des roues pour changer la jante n’est pas des plus évidents et une urgence est vite arrivée.

Quatrième visite : Rien

Je suis revenu pour la quatrième fois décidé à repartir à vélo théoriquement, à pied en pratique. Ça fût rapide, à ma vue le patron m’a demandé de repasser le lendemain.

Cinquième visite : Toujours rien.

Comme la veille, j’y suis retourné et suis reparti à pied. Entre temps j’ai tout de même fait des recherches de mon côté savoir de quoi il en retournait et effectivement, les avis sur cette entreprise ne sont pas tendres. En particulier venant des personnes ayant souhaiter profiter de l’opération nationale Coup de Pouce vélo. J’ai également découvert que l’entreprise a changé de main en 2018 suite à la faillite de l’ancien propriétaire et que comme je le soupçonnais la personne actuellement en charge avait en réalité une formation pour deux roues motorisés uniquement.

Sixième visite : La fuite.

J’ai finalement récupéré mon vélo, en état de rouler. Appelé en début d’après-midi, on m’annonce que les réparations ont été faites et que je peux passer récupérer mon vélo. Détail, la maison ne prend que le liquide. Sur place, je ne m’attendais plus à rien et j’ai quand même été déçu. Non seulement la procédure avait été particulièrement longue, mais en plus, ce ne sont pas mes jantes mais l’intégralité de mes roues qui ont été remplacées. Refusant de faire traîner l’affaire, j’accepte mon sort et sors les billets. Je signale tout de même l’absence de catadioptres sur ces roues (Ce qui est illégal) et que j’aurais souhaité récupérer ceux de mes anciennes roues. Long balbutiement où on m’invite à me servir sur un des autres vélos présents, j’arrive à obtenir la promesse que mes catadioptres seront disponible le lendemain, encore… Oh, est-ce que j’ai précisé que les nouvelles roues n’ont rien de neuf ? La moindre des choses dans ce cas aurait été d’avertir, demander l’accord du client voire de cacher la chose correctement en enlevant l’aimant de compteur sur les rayons.

Septième visite : La fin.

J’ai finalement pu récupérer mes catadioptres, ainsi que mon attache rapide sécurisée, dans ce qui s’apparente à une décharge métallique dans l’arrière cour de l’établissement. À l’arrivée, une semaine après la dernière visite, le patron était tranquillement avachi sur sa chaise à jouer sur son smartphone et n’a même pas eu la décence de trouver une excuse quant à l’absence de catadioptres à l’accueil. Il m’a conduit jusqu’à la cour où il m’a tout simplement laissé me servir pendant qu’il retournait à ses occupations.

Venu pour un remplacement de jantes, on m’a fait revenir à maintes reprises pour qu’au final je paie à un prix exorbitant des roues d’occasions. Des réglages auraient été faits sur le vélo : les freins étaient inutilisables puisque frottaient sur le pneu plutôt que la jante, les changement de vitesses étaient impossibles et la roue arrière n’était pas alignée. J’ai voulu gagner du temps et avoir un service raisonnable, j’ai simplement pu sortir mes outils et refaire le travail moi-même.

Modification 2023-01-01 : La boutique est en travaux et change de propriétaire.

I love a good romantic tale, even of the overwrought variety (I am a The Notebook enjoyer). Therefore I was happy to give Big Dipper a try, which is a short, kinetic (choice-free) visual novel about a romantic encounter on New Year’s Eve. In case you’re wondering, it’s all very chaste stuff; the title is no naughty double entendre.

Developed by Team Zimno from Russia [*], the story is told from the perspective of Andrew, a somewhat sullen young man who encounters his manic pixie dream girl when a woman named Julia literally sleepwalks into his life and his cabin.

The game throws in a bit of the supernatural, but it’s over after less than two hours, so it doesn’t really go very far with any of it. That’s a shame, because earnestly incorporating Slavic folk tales could have made things a lot more interesting!

The relationship between Andrew and Julia develops implausibly. They grow closer through sharing stories of loss of alienation with each other, but the romance is otherwise just rushed along a “they dislike each other → they love each other beyond measure” path without ever building genuine momentum.

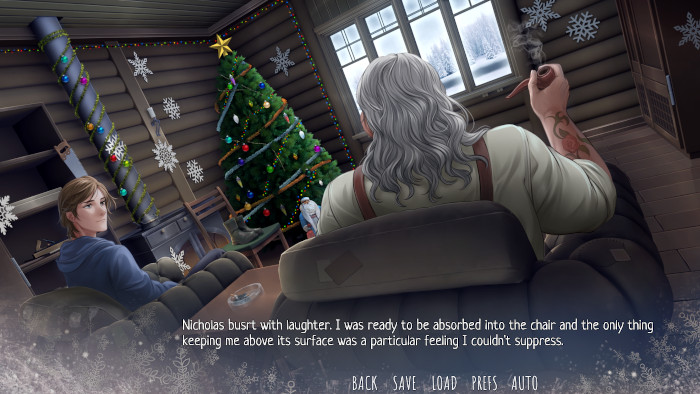

We’re only in the first scene, and there are already typos like “busrt” instead of “burst”. (Credit: Team Zimno. Fair use.)

Big Dipper certainly gets the aesthetics right. Made with Unity, the game looks better than your average visual novel, with nice animations for the snowfall outside and the cozy fireplace inside. The character art and full-screen graphics also look good, and are enriched with chibi-style pictures during key scenes.

Unfortunately, it’s hard to overlook the shortcomings. Aside from a rushed story that doesn’t withstand the slightest scrutiny, it’s difficult to justify the lack of attention to detail in the writing. You’ll notice the first typos and misspellings just a few paragraphs in, and we’re talking about glaring ones (“busrt” instead of “burst”, “cheked” instead of “checked”) that could have been caught with any spell checking tool.

Big Dipper is only $5, but you’ll find much better romantic visual novels even for free. Unless you’re desperately looking for a winter-themed pick-me-up and are willing to look past its issues, you can safely skip it.

[*] It’s worth noting that the authors have publicly spoken out against Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and against Vladimir Putin.

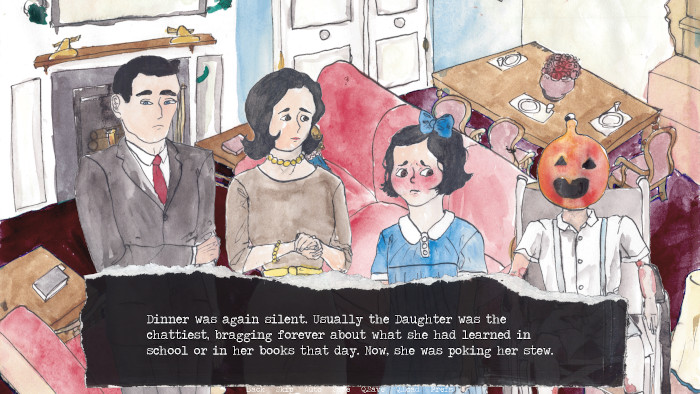

Pumpkin Eater is a kinetic visual novel, which means that it’s a story with art and sound, but with no player choices. The $2 regular sales price suggests a short story, and indeed I finished it in about 30 minutes.

Given how short it is, I don’t want to give too much away. In a nutshell, it’s about a family who loses a child in an accident but cannot let go. What follows is a tale of decay and insanity, told in (the authors assert) a medically accurate manner.

The characters and backgrounds are lovingly painted in watercolor, which creates a contrast with the story’s morbid content. (Credit: thugzilladev. Fair use.)

I appreciate attempts to demystify death, even if it’s done in the form of a horror story. Ultimately, that seems to the point of the game, which comes complete with a glossary.

The story is engaging, and it uses music and sound effects well. It won’t scare your pants off, but it might make you lose your appetite. It is also likely to stay with you. 3.5 stars, rounded up.

When governments, corporations and other organizations act unethically or illegally, only people on the inside may know about it. If they choose to tell someone who might bring about change, they become whistleblowers.

Published in 2001, C. Fred Alford’s Whistleblowers: Broken Lives and Organizational Power examines the personal sacrifice it takes to oppose an organization’s actions. From interviews and a review of prior research, Alford concludes that in spite of many legislative attempts to protect whistleblowers, retaliation is the norm, not the exception.

How organizations fight back

Whistleblowers are often not fired immediately. They are moved to “offices” that previously served as closets; their responsibilities are curtailed; their performance is put under a microscope. Only after sufficient time has passed to create distance to the act of whistleblowing, they are fired, frequently for “poor performance”.

After losing their job, they may find it impossible to work in their chosen sector again, thanks to informal blacklists. Whistleblowers are portrayed as “nuts and sluts”, their sanity and character called into question. As Alford puts it, the process is complete “when a fifty-five-year-old engineer delivers pizza to pay the rent on a two-room walkup.”

Considering this characterization, one might expect Alford to support whistleblower anonymity. Not so—anonymity, he claims, is a road to nowhere (p. 36):

Anonymous whistleblowing happens when ethical discourse becomes impossible, when acting ethically is tantamount to becoming a scapegoat. It is an instrumental solution to a discursive problem, the problem of not being able to talk about what we are doing. Whistleblowing without whistleblowers is not a future we should aspire to, any more than individuality without individuals or citizenship without citizens. If everyone has to hide in order to say anything of ethical consequence (as opposed to “mere” political opinion), then we will all end our days as drivers on a vast freeway: darkened windshields, darkened license plate holders, dark glasses, speeding aggressively to God knows where.

Personally, I think an “instrumental solution to a discursive problem” is still a fine solution, especially if it happens to save lives or serve the public interest. Much as Alford agonizes about the sacrifices whistleblowers make, he seems unwilling to imagine a world in which those sacrifices can be lessened.

Psychoanalysis to the rescue

Because many of the people Alford spoke with attended self-help groups (which selects for trauma), and because his book rarely deals in numbers, it’s difficult to say how statistically valid his observations are. Much of the book is focused on psychoanalysis: What causes whistleblowers to act, and how do they process the consequences of their actions?

Alford theorizes that whistleblowers are motivated by what he describes as “narcissism moralized”. To put it another way, whistleblowers can tolerate the alienation from everyone else more than they can tolerate being in conflict with their idealized moral self.

It’s a reasonable argument, considering that whistleblowers often act alone—so their impulse to act is often likely the result of an inner conflict. But when he characterizes whistleblowers’ motives and feelings, Alford readily dismisses evidence that isn’t consistent with his own views.

In describing one case, he writes: “Ted protests too much. For that reason I distrust his account” (p. 39). This kind of reasoning makes me worried that the author may be an unreliable narrator of whistleblower motivations, and I would rather read more quotes and fewer abstract characterizations.

How many whistleblowers discuss their actions with loved ones beforehand? How many are deeply appalled by imagining the consequences of the organization’s actions on the outside world? What Alford offers us are generalizations, made more tedious with frequent repetition and verbosity, for example, when he writes about the state of “thoughtlessness” (p. 121):

Thoughtlessness stems not merely, or even primarily, from fear. Thoughtlessness arises when we are unable to explain our fears—that is, make them meaningful, comprehensible, knowable. This happens when we lack the categories to bring our fears into being. Common narrative is, I’ve argued, of little help in this regard.

Social theory could be more helpful than it is. Liberal democratic theory assumes that politics is where the action is, and so it assumes that individualism is possible. Foucault’s account assumes that individuals don’t exist. Neither approach gets close enough to life in the organization, to say nothing of the lives of those who suffer the organization, to help individuals make sense of the forces arrayed against them.

If you enjoy the kind of analysis that says in 100 words what could be said in 10, you’ll find plenty of it here.

The Verdict

In fairness, Whistleblowers is a short book (170 pages including the index), and it does tell some interesting stories about different types of whistleblowers in different fields, from engineering to accounting.

It offers some metaphors which I’ll almost certainly find myself using again—for example, it describes life after whistleblowing as akin to space-walking, because many whistleblowers have learned the hard way that the world doesn’t work the way they thought it did.

The most useful takeaway from Alford’s book is a deeper understanding of the often very heavy cost of whistleblowing. Alford ultimately characterizes it as a “sacred” act; I would compare it perhaps with blasphemy. To understand the cost of telling the truth should prepare us to lessen it.

Gabriel ist jung Vater geworden und lebt mit seinem Sohn Jamie. Er ist in einer Clique von Skatern. Gabriel hat ein Samurai-Schwert und, ähnlich wie im Film “Ghost Dog”, werden Samuraisprüche während des Films erzählt. Gabriel lernt Corry, die Freundin seines Freundes Joel, kennen. Corry, Joel und Gabriel nehmen Drogen, steigen im Rausch in den Züricher Zoo ein und lassen zwei Pumas und eine Giraffe frei. Jamies Mutter Mutter ist Fernsehsprecherin und berichtet über die freigelassenen Tiere. Gabriel und Jamie gehen auch einmal zum Haus der Fernsehsprecherin um Jamie’s Mutter Zoé zu besuchen. Es ist gerade Party dort, und dem Mädchen ist schwindlig. Ein paar Tote und Verletzte später endet der Film.

Soul of a Beast ist ein etwas schwieriger Film. Es sind sehr viele Elemente hineingemischt, egal ob Szenerie, Situationen, Stilmittel, verschiedene Kulturen wie Asien, Europa, Afrika, Südamerika, Natur, Stadt, real, unter Drogen, Friede, Militär, Polizei. Es wirkt ein bisschen als wäre es der letzte Film den Lorenz Merz in seinem Leben machen könnte und alles enthalten sein muss. Die 100 Minuten reichen bei weitem nicht aus um diese Elemente vernünftig zu entfalten. Ausser die Dialoge - die sind sehr kurz. Zu kurz vielleicht. Ausser von der Grossmutter erfährt man kaum etwas von den handelnden Personen, sie kommen und gehen. Viele Szenen sind irgendwie dunkel, blutverschmiert, meist voller Müll. Die Umgebung wirkt immer überladen, überzeichnet. Gabriels Auto ist voll, Gabriels Wohnung ist voll, Zoé’s Mutter hat viele Bedienstete. Im Wald ist es nur grün, völlig unmotiviert steht auf einmal ein einzelner gut getarnter Soldat auf, der Zürisee ist schön. Am Ende bleiben Fragen über Fragen, es bleibt das dumpfe Gefühl dass irgendwas fehlt.