Latest reviews

In the late 19th century, as the United States fully consolidated itself and its territory (through war and ethnic cleansing), its elites began to realize openly imperial ambitions. These ambitions reached a fever pitch in the Spanish-American War, which led to the US establishing control over Puerto Rico, the Philippines, Guam, and (nominally independent) Cuba.

When Smedley Butler, the son of an influential Pennsylvania family, joined the US Marines in 1898, he was caught up in the war fever of the time. But instead of fighting the Spanish, he soon found himself helping to police America’s empire on behalf of its most powerful economic interests.

Decades later, Butler, now a Major General, started to write his own script. In 1933, he alleged that he was invited to take part in a conspiracy among wealthy businessmen to overthrow U.S. President Roosevelt and install a dictator.

It became known as the Business Plot. A congressional committee concluded that “there is no question that these attempts were discussed, were planned, and might have been placed in execution when and if the financial backers deemed it expedient." Nobody was prosecuted.

In his final years, an increasingly radical Butler gave fiery speeches and penned a short book called War is a Racket. It contains the following passage:

I helped make Mexico, especially Tampico, safe for American oil interests in 1914. I helped make Haiti and Cuba a decent place for the National City Bank boys to collect revenues in. I helped in the raping of half a dozen Central American republics for the benefits of Wall Street.

Late in his life, Butler denounced war and empire, and fought for veterans’ rights. (Credit: Bettman/Getty Images. Fair use.)

Legacies of Empire

For American journalist Jonathan Katz, Butler’s life presents a lens through which to view the history of American imperialism, and its modern legacies. In Gangster of Capitalism, Katz traces Butler’s career in the military and his stint as Philadelphia’s “Director of Public Safety”, a role in which he waged a brutal war on crime in the city.

Katz makes it clear that Butler, in spite of his Quaker upbringing, committed truly horrific and violent actions, and often rationalized them through the pervasive racism of the time. As part of the nearly 20-year-long occupation of Haiti by the United States, Butler instituted de facto slavery to build up the country’s infrastructure.

Unlike the opaque Business Plot, the corporate interests that profited from these endeavors and drove US policies are well-documented, from bankers to landowners to oil companies. Franklin Roosevelt himself pursued personal agriculture investments in Haiti while helping direct its occupation as Assistant Secretary of the Navy.

In each chapter, Katz describes the modern legacy of American imperialism, including by quoting Haitians, Filipinos, Chinese, and others he has met. While Americans have forgotten the little they have ever known of this history, the citizens of these countries have not. Katz’s travelogue enriches the book and makes this history tangible.

Past and Prologue

Gangsters of Capitalism is an accessible, informative and engaging book. At no point does Katz turn from facts to polemic. He gives clear-eyed accounts of the brutal regime of Nicaragua’s leftist autocrat Daniel Ortega, and the imperialist ideology of China under Xi Jinping. The book is a critique of empire, not an anti-American screed.

It is also a timely book, as another imperialist power, Russia, wages a war of aggression against neighboring Ukraine. What role should Western powers play today to counter such naked brutality? Can military alliances like NATO protect the peace in the 21st century? What alternatives are there?

The invasion of Ukraine marks a new chapter in world history, and we all benefit from remembering previous chapters—including America’s own brutal imperial history—to navigate the moral landscape now before us.

Dexter war vor Jahren eine meiner Lieblingsserien und das ging bestimmt nicht nur mir so. Innerhalb der ersten vier Staffeln wurde die Handlung um den Serienmörder in Diensten der Polizei spannend und gut inszeniert herübergebracht. Die weiteren vier Staffeln kamen nicht mehr an das Niveau der anderen heran aber trotzdem bleib ich dabei um zu erfahren wie es weitergeht. Und am Ende der achten Staffel war für mich klar, das es nicht mehr weitergehen kann. Der Abgang Dexters hat für mein Empfinden keinen Spielraum für eine Rückkehr gegeben. Tja, was soll ich sagen? Ich habe mich getäuscht.

Die Geschichte startet in einer US-amerikanischen Kleinstadt und ich war von Anfang an wieder im Dexter-Fieber. Vergessen war das seltsame Ende der achten Staffel. Die Stimmung im winterlichen Handlungsort ist gut eingefangen und wird rund um den Hauptdarsteller gut aufgebaut. Auch wenn in der ersten Folge für Neulinge nicht ganz klar wird, was hier eigentlich los ist. Diese Folge wird meiner Meinung nach nur zur Schaffung der Atmosphäre verwendet. So kommen auch Leute, die bisher keinen Kontakt mit Dexter Morgan hatten, in die Dexter-Stimmung.

Anfangs ist unklar wer welche Rolle hat. Wer ist der Böse, wer nicht und wann kommt es zur ersten Dexter-typischen Handlung. Der Reiz und die gut eingefangene Atmosphäre haben mich die komplette Staffel in drei Tagen durchschauen lassen und es war zu keinem Zeitpunkt langweilig. Die Spannung wird gut aufgebaut und es wird langsam aber sicher klar wer welche Rolle spielt und welches Schicksal diese Personen erleiden werden.

Warnung: Der untenstehende Text enthält Spoiler.

Diesmal wird es leider endgültig keine Fortsetzung geben. Aus dem für mich nicht hervorsehbaren Ende kommt selbst Dexter nicht mehr heraus. Aber wer weiß ob sein Sprössling nicht den selben Weg einschlägt und wir in ein paar Jahren eine weitere Staffel zu sehen bekommen. Wir werden es sehen.

Vampire Survivors by indie developer Luca “poncle” Galante was released in December 2021. It only costs $3 and is still in early access, but has already racked up tens of thousands of “overwhelmingly positive” reviews on Steam.

The game’s formula is simple but brilliantly executed, once you look past its rudimentary 16-bit style pixel graphics. Your goal is to survive for 30 minutes against ever-growing mobs of monsters. You start with a single weapon, but as you defeat monsters, you level up quickly. So far, that sounds like many twin-stick shooters.

The game-changing part of the Vampire Survivors formula is this: There’s no need for button-mashing, as your character auto-fires all weapons at their maximum firing rate.

As someone who quickly gets controller fatigue from many action games, I found it surprisingly chill to play, in spite of the amount of stuff happening on the screen. You avoid enemies, destroy them with an ever-growing arsenal of weapons, collect experience gems, and level up.

Power-ups from hell

Level up enough, and the game’s promise that “you are the bullet hell” becomes fulfilled. It’s hard to convey just how insane things can get. Consider that this shows only a mid-level build:

Character “Krochi” facing an onslaught of monsters in the first stage. (Credit: Luca Galante. Fair use.)

To make it through 30 minutes, you need to continually improve your build, and combine items into ultra-powerful “evolved” weapons. You can also use collected coins from a run to buy persistent power-ups that will help you with all future runs.

It won’t take you more than a few hours to master the first stage, but Vampire Survivors has lots more to offer. You can unlock many different characters (who may have their own unique weapons), additional stages, and additional difficulty levels.

While the maps are generally super-simple, there are a few surprises. For example, the “Dairy Plant” map features new mechanics, such as little carts you can push in the direction of oncoming enemies, and special floor tiles that trigger enemy waves to spawn.

Challenging but not limitless

Even though it is still in early access, Vampire Survivors easily offers 10-20 hours of frantic play as of this writing; content updates have been forthcoming at a rapid clip. If you like action games and don’t find the visual intensity offputting (or worse), you’ll definitely want to check it out.

Unlike roguelikes that offer nearly endless challenges, most players will eventually hit a ceiling as they accumulate persistent power-ups and develop ever-more successful builds. But for $3, that’s still a hell of a lot of entertainment (no pun intended), and anyone trying the game now should revisit it again in a few months as it continues to be expanded and balanced.

I played Vampire Survivors on Linux using Proton without issues (I did have to set the launch options to PROTON_LOG=1 %command% as recommended on ProtonDB).

Additional reading

-

In February, NME published a nice interview with developer Luca Galante.

-

As usual, a Fandom wiki has quickly popped up; if you don’t want to discover every combo for yourself, the weapons evolution guide in particular is indispensable.

What if you took some of the best ideas from the roguelike deck-building genre, but instead of being dealt cards, you rolled dice on each turn? That’s the premise of a ridiculous, addictive, and sometimes frustrating game called Dicey Dungeons.

Developer Terry Cavanagh has published indie games since at least 2008, but his breakthrough titles were the puzzle platformer VVVVVV (2010) and the brilliant twitch game Super Hexagon (2012).

When I first looked at Dicey Dungeons, I was not especially enamored. Anthropomorphized dice, really? The moment you start actually playing it, the game’s self-aware sense of humor makes it all work.

You play as the contestant in a gameshow whose host, Lady Luck, promises to fulfill your innermost desires if you win. The catch? You’re transformed into a dice and are doomed to compete in Lady Lucks’s dungeons forever, with the game clearly rigged against you.

Revenge of the bloodsucking vacuum cleaners

The maps are the least interesting part of the game, but they do show you all the enemies you can fight in a given level. In this case, you can go up against a marshmallow, a coin-stealing kid, and a sickly hedgehog. (Credit: Terry Cavanagh. Fair use.)

The enemies you encounter are not the standard fantasy fare. Instead, your next opponent could be a bloodsucking vacuum cleaner, a snowball-throwing yeti, a poisonous ice cream cone, or a guy whose entire head is a home stereo system.

Battles are turn-based. On each turn, you roll a number of dice, which you then drag and drop to a compatible item in your inventory. You may not have one! For example, all your items might require even numbers, and you might roll a bunch of threes.

It’s a simple enough concept, but with a large variety of enemies and items, it adds up to a rich gameplay experience. By itself, that could make for a 5-10 hour game. What makes Dicey Dungeons a 30-60 hour game is its willingness to throw its own rules by the wayside.

Rules, schmules

As you play the game, you unlock new characters with their own sets of items, and with completely different play styles. For example:

-

a character that casts spells from a spellbook with a fixed number of slots, of which up to four can be active at any given time.

-

a character that, instead of rolling dice, generates random numbers towards a fixed target value. If you hit that target value exactly, you get a jackpot reward.

-

a character that is dealt a set of cards in random order, combining true deckbuilding mechanics with dice.

Moreover, each character advances through six episodes that play with rules in interesting ways. The most interesting of these are the “parallel universe” episodes (in which items and status effects work completely differently) and the bonus episodes (in which you gradually accumulate randomized rules like “after 4 turns, all enemies transform into bears”).

It all culminates in a final confrontation which, again, does something completely new and interesting with the game mechanics. I won’t spoil it for you; suffice it to say that there’s a lot to keep the player engaged. And when you’re done with that, there are some (fairly easy) Halloween bonus episodes as well.

As with Super Hexagon, Cavanagh again collaborated with Chipzel on the music. Unlike the high octane chiptune sound of Super Hexagon, Dicey Dungeons’ soundtrack blends in jazzy flavors, which give the game a unique feel.

The game’s wit and humor come through in many places, such as when visiting shops. Sometimes the shopkeepers will even remark on specific enemies in the level you’re in. (Credit: Terry Cavanagh. Fair use.)

Dice with rough edges

The game is not perfect. My criticisms of it can be summed up in three categories:

-

Pointless maps: The game features suitably atmospheric levels such as “the libary” or “the dark forest”. But the actual dungeon maps are extremely linear and basic. The most complex choices you’ll make navigating the dungeon are branching questions: This enemy first, or that one?

-

Luck over strategy: Being at its heart a dice game, Dicey Dungeons can be incredibly unfair. An enemy can roll two sixes twice in a row, hitting you with maximum damage and status effects, while you are barely able to make a dent due to a poor roll.

In theory, you can sometimes flee a battle. But that action is almost useless. You’ll still have all your damage, and in many cases you won’t progress unless you defeat the enemy. So, go against the same enemy again with three hit points left, while they’re back at full strength? Good luck! -

Inconsistent execution quality. The spellbook user experience, for example, is very clunky—the drag and drop mechanics are poorly explained and not intuitive. Even though the mechanic had promise, I had the least fun playing that character, just due to the interface feeling so unpolished.

Each character’s list of episodes includes an “elimination round” which, as the name suggests, exists to prevent straightforward progression. It achieves this by making the enemies’ items a lot more powerful. Unfortunately, this can lead to a high number of unwinnable encounters.

The Verdict

Those criticisms shouldn’t distract from the fact that Dicey Dungeons, overall, is a hell of a lot of fun to play. There’s a lot of love in the details, from the silly unlockable enemy biographies, to the clever dialogue during encounters or shopkeeper visits.

I would give the game 4.5 stars, rounded up because of the sheer amount of gameplay variety and content. If you enjoy the deckbuilding formula, and are looking for something similar that may keep you entertained for a few weekends, go and roll those dice—you might get lucky!

The explosion of indie gaming in the 2010s has blessed players with the triumphant return of genres largely written off by major publishers, from 16-bit-style “metroidvanias” to point-and-click adventures. The flip side of this blessing is the problem of discovering the indie gems you truly want to play. That’s where Hardcore Gaming 101’s Guide to Retro Indie Games comes in.

On 152 richly illustrated pages, the first volume presents detailed overviews of many games which, while mostly released in the 2010s, seemed “retro-styled” to the editors. It is, as they acknowledge, a squishy definition:

It’s primarily to refer to games that would be inviting to fans of classic video games, rather than a specific style. For example, even though Night in the Woods doesn’t have a pixel look, it’s still recommended for adventure game aficionados.

To be sure, you won’t find on these pages the kinds of indie games that are going head-to-head against big-budget, “triple A” open world RPGs or first-person-shooters. If there is going to be a shooter, it’ll be a “boomer shooter” in the style of the original 1990s trailblazers like Doom or Duke Nukem.

Straight to the point

The guide focuses on gameplay above all else. Don’t look to this volume for information about the developers, how the games were made, or technical details. The tiny infobox about each game contains its title, the year it was published, and the platforms it’s on—that’s it.

The platform list at least is exhaustive, condensed into three letter abbreviations ranging from the obvious (“WIN”, "PS4”) to the obscure (“AFT”, “PAN”). Thankfully, there’s a system key on the first page.

Each article is somewhere between a review and an overview, and seems intended to help the reader answer two questions: How good is it, really? And, is this game for me?

Games are typically described in two pages, and every single page is richly illustrated. (Credit: Hardcode Gaming 101. Fair use.)

On the whole, I found the articles fair and informative, helping me prioritize my backlog and discover some new games. In a couple of cases, the articles went a little too close to spoiler territory for my liking, but that can be hard to avoid when writing about a story-driven game like Lisa or Undertale over multiple pages.

Not a true guide, but still a great introduction

To be truly a guide rather than a collection of articles, the Guide to Retro Indie Games would have benefited from some chapter introductions to the developers or the genres represented here. Nonetheless, if you love indie games and enjoy reading about them in print, I definitely recommend it.

One caveat: the first copy I ordered had severe print quality issues. That kind of thing happens especially with small publications, and Amazon quickly sent a free replacement, so it’s not reflected in the review score. I also bought the second volume, which did not have the issue.

The first printed copy I ordered from Amazon had significant color misalignment issues on every page, rendering the screenshots blurry and almost unreadable. (Credit: Hardcode Gaming 101. Fair use.)

The full list of games in the first volume follows (grouped by publisher):

The Shivah

The Blackwell Series

Gemini Rue

Resonance

Primordia

Technobabylon

Shardlight

Kathy Rain

Thimbleweed Park

Nelly Cootalot

Always Sometimes Monsters

Read Only Memories

Va-11 Halla

Night in the Woods

Pony Island

Mercenary Kings

Flinthook

Odallus

Oniken

Noitu Love

Rogue Legacy

Super Time Force

Volgarr the Viking

Freedom Planet

Westerado

VVVVVV

Shovel Knight

Super Meat Boy

Ultionus

Mystik Belle

Guacamelee!

Axiom Verge

Owlboy

Dust: An Elysian Tail

Hyper Light Drifter

Alwa’s Awakening

Undertale

Lisa

Barkley, Shut Up and Jam: Gaiden

Severed

One Finger Death Punch

Not a Hero

Assault Android Cactus

Hotline Miami

Crimzon Clover

Blue Revolver

Hydorah

l’Abbaye des Morts

Maldita Castilla

The Curse of Issyos

Il locale si presenta molto piccolo, ma ha riservato una sorpresa inaspettata per quanto riguarda il cibo, veramente buonissimo.

Ogni piatto aveva sapori e gusti straordinari - vi consiglio di provare i loro burger, io ho mangiato il Don Chisciotte e ne sono rimasto estasiato.

Tornerò sicuramente.

p.s.: fanno sia colazione, che pranzo, che cena.

Picross is a long-running Nintendo games series that revolves around solving Nonograms, a popular Japanese logic puzzle. The series has been so influential in the popularisation of Nonograms that many people only know them by that name. The puzzle requires filling a grid according to sequences of numbers on the side. Each row and column on the grid has such a number sequence. Following the rules, a cell in the grid is either filled or left empty. Once done, they form a picture.

It’s somewhat similar to another popular Japanese logic puzzle, Sudoku, in that it offers practically infinite puzzle variations and a simple set of rules to complete a puzzle. But contrary to Sudoku, where you have to choose a number ranging from one to nine to fill a cell, for Nonograms, the choice is binary. It is a much simpler type of puzzle in comparison. But in turn, it gains some flexibility. For Sudoku, the grid is fixed in size, whereas Nonograms have arbitrary width and height.

The way I play these two puzzle games totally differs, however. A Sudoku puzzle can be hard to crack, and it is fun spending minutes eliminating possibilities until you’ve found a progression path. With Nonograms, it is the most fun trying to solve them as fast as possible. The significantly easier ruleset allows for this. And with filling a grid cell being a binary choice, it is much easier digitised to a simple button press than Sudoku is. Everything about Picross lends itself to this fast playstyle, and it is a tonne of fun.

With this introduction out of the way, let’s talk about the actual game this review is about.

The actual game

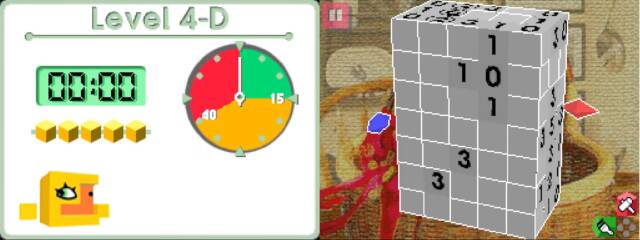

Picross 3D is HAL Laboratory’s attempt at extending this two-dimensional puzzle classic by another dimension. Instead of a grid of cells, you start with a cube that subdivides into many smaller cubes. And instead of constructing a pixel image, you form a voxel sculpture out of the cube.

With this, you can’t really have sequences of numbers on the side. So for this game, it is simplified to one number per line. Although, it’s not quite that simple. Sometimes a number has a modifier, indicated by having the number painted within a square or circle. The number tells you how many consecutive blocks in the line remain part of the final sculpture, and the modifiers tell you how many gaps are allowed in the sequence of blocks.

The game primarily uses the Nintendo DS’s touchscreen for controls. Whereas with other Picross games on the platform, touchscreen controls were optional, here they are mandatory. With the stylus, you rotate the puzzle to look at it from all directions. It works the same with marking cubes to be kept or destroying them.

One nice thing, that differs from how Picross usually works, is that cubes that are marked to be kept cannot be destroyed without unmarking them first. This is great, as the risk of misclicking is high, especially on larger puzzles. It shows that a lot of consideration went into how this game differs from the rest of the series and how its unique qualities necessitate certain things to be different.

Since the puzzle is in 3D, you also have to have the ability to look inside the puzzle, to see things that would be otherwise obscured by other cubes. For this, you can slice the puzzle along the three axes to get a cross-section.

Another unique thing about this game is that it features a rating system. On completion, you can earn up to three stars. One star is always guaranteed. You get another if you solve the puzzle under a certain time threshold. And the final one is earned for not making any mistakes.

The game is broken down into levels that contain a collection of puzzles, and you can advance to the next level after collecting a certain amount of stars.

The other major distinguishing factor of the game is its aesthetics. Picross games are usually quite stylistically plain. This game has a much more distinct visual identity. It features a mascot that is a cube with a face on it that makes celebratory dances as you solve puzzles.

A newly started puzzle with the game’s mascot in the bottom-left. (Credit: HAL Laboratory. Fair use.)

What it feels like

The addition of another dimension to a 2D puzzle game sounds simple enough, but here, it significantly shifts the overall game feel. What was added in terms of complexity was trimmed elsewhere in turn. For example, there might be lines going into three different directions now, but each can only feature one number, instead of multiple, like in classical Picross. The overall logical complexity is similar but achieved through different means. These differences have further side effects on the gameplay beyond just the new controls.

Picross 3D plays very differently from classical Picross, in that the act of solving is much more slow and deliberate. The three-dimensional nature of the puzzles results in you never seeing the whole puzzle at once. Realistically, you can only look at two dimensions at once while solving. In practice, this results in a constant shifting between the three dimensions.

The controls also foster a more deliberate playstyle. Because of the 3D perspective, the cubes heavily vary in size and shape due to their projection onto a 2D screen. This makes misclicking very easy, and thus you have to go slow to avoid mistakes.

The game further incentivises methodical play with its rating system. Making mistakes in this game is easier than ever, and if you make one, a star will be subtracted from your three-star rating.

With all that said, you can probably see that my usual way of playing Picross is on a collision course with this game.

What I don’t like

The required deliberateness during puzzle solving results in a lot of downtime, where you aren’t as much solving a puzzle as you are searching for the next line to advance on. Standard Picross has this too, to an extent. But since you have a full view of the puzzle at all times, downtime due to searching is much smaller. This is especially true once you realise the locality principle to solving standard Picross. When you progress on a line, the corresponding row or column orthogonal to it is also affected, and most of the time, you can directly progress from there. Thus it forms a chain of actions with minimal downtime. As a result, this lends itself to playing the game quickly and is a tonne of fun. And this is the problem with Picross 3D. The puzzles aren’t more challenging, but, due to their 3D nature, are slower to solve. Thus it removes the integral fun component for solving Picross for me and, unfortunately, doesn’t add anything to replace it. The greater emphasis on visual style was enough to keep me playing initially, but after several hours that wore off. After that, the game was just a slog to play.

Furthermore, I have several technical complaints. Once you get into the later stages of the game, the puzzles get big and quite unwieldy. The puzzles take up the entire screen, and looking at multiple dimensions simultaneously, requires you to shift your view around constantly to see what goes over the edges of the screen. The puzzle slicing is even worse. Slicing the puzzle to see only parts of it resizes it on screen accordingly. This produces the problem that when you slice in, the game zooms in, but once you want to slice out, due to the zoom, the point you would have to reach to slice out fully is out of the frame. You have to slice out as far as the screen allows for and redo the motion until you are done. And because of the size of the puzzles, you have to do slicing like this constantly. It’s very annoying.

And again, on larger puzzles, there are severe issues with aliasing, which makes numbers hard to read at certain angles.

Conclusion

Picross 3D seems like a natural and simple extension of standard Picross, but that assumption would be wrong. Bringing Picross to the third dimension significantly alters the gameplay. So much so that it removes why I play Picross in the first place.

The larger puzzles are especially problematic. Not only are the base problems further exacerbated by them, but the game doesn’t even appear to be built to deal with the sheer volume of cubes that make up those puzzles. They make the case that bigger isn’t necessarily better — sometimes it’s just bigger.

4/10

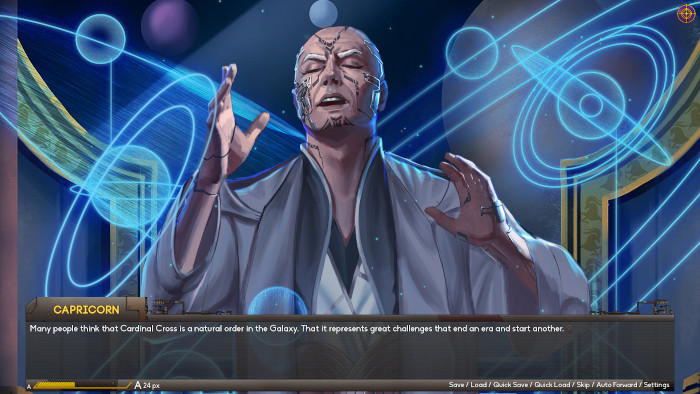

Cardinal Cross is a choice-driven visual novel about a space-traveling scavenger named Lana Brice, who unexpectedly finds herself caught up in a galactic conflict of an astrological nature. The game was written by Roman Alkan and published through her small indie studio LarkyLabs under its ImpQueen brand.

In this universe, predictions derived from the movement and position of celestial objects are as fictionally real as the Force in Stars Wars, or as the fungal excretions of sandworm larvae that make interstellar travel possible in Dune. In most other ways, Cardinal Cross employs familiar sci-fi tropes: cybernetic implants, space rebels, robots and AI, the works.

Lana Brice (left) is a space scavenger with strained family ties. (Credit: LarkyLabs. Fair use.)

Meet the factions

Lana Brice and her friend Wiz, the Mechanic, are part of group of planets known as the Raiders. These folks have gotten the short end of the stick in a conflict with another group known as the Morai System, and they’re generally treated like colonies.

In a black market transaction, Lana and Wiz come in contact with a rogue intelligence agent of the Morai, who is trying to purchase an artifact from them. Most people have cybernetic implants, but this guy is enhanced to the point of almost losing his humanity. He is dangerous, and so are his former employers.

Soon enough, Lana is caught up in a web of conspiracies and plots involving multiple factions. At its center is an astrological supercomputer which the Morai elite use to maintain power and control. Its predictions are not perfect: so-called “howlers”—some humans, objects, planets—elude it completely. (I’m guessing the term is a reference to errors and aberrations rather than monkeys.)

As you might expect from its astrological theme, much of the story revolves around whether our fates are our own to write if the stars seem to already foretell what they are. Thankfully, the story never gets bogged down in sophomoric arguments about free will—it plays out more viscerally through Lana’s choices. That is to say, your choices.

One way or another, Lana’s fate is in the stars. (Credit: LarkyLabs. Fair use.)

Choices and characters

Throughout the story, you get to make more than 100 decisions, typically about things to say, sometimes about things to do. A lot of them have a negligible effect, but you can romance three different characters, influence Lana’s personality, and achieve multiple endings.

The game signals the most important choices with a sound effect, and it makes it clear when you have the option to embark on a romantic adventure. It also displays the effect you have on others (“[name] is annoyed”, “[name] is amused”). These messages are sometimes off-point and immersion-breaking, but you can disable them entirely.

Cardinal Cross is not voice-acted, but it is exceptionally well-illustrated. Not only does it have beautiful character art, it has a ton of it.

There are 50+ side characters, and most of them are visually well-differentiated. It includes 70+ full-screen graphics during special events (“CGs” in visual novel lingo). In case you’re wondering: the graphics for the romantic outcomes are about as tame as what you’d find in a PG-rated movie.

The game has a soundtrack by Jeaniro, which creates suitable ambience without distracting from your reading experience. During the story’s most dramatic moments, the music becomes boisterous or tense, generally fitting the text well.

The story is substantive, but it doesn’t overstay its welcome. I reached an ending which suited my choices well in about 6 hours. After I checked out one other ending with the help of a guide, my total playtime added up to 8 hours.

A good yarn with a few flaws

Roman Alkan’s world-building helps to set the stage effectively, even if the introduction of the in-universe terminology is a bit tedious at first. I had three main issues with the writing:

-

It would have benefited from more editing (there’s some dialogue that’s a bit awkward; there are a few spelling/grammar issues throughout).

-

There are too many characters to keep track of, and the story shifts too quickly between them.

-

Relatedly, the story doesn’t give enough space to some key dramatic moments for us to really grapple with what just happened.

Know that it’s a violent game. Both Lana and the other characters may hurt—and kill—people they come across. Cardinal Cross does not explore its darker themes with the same sensitivity some visual novel writers (like Christine Love) bring to their work; here, transgressions don’t always have the reverberations you would expect.

All in all, though, it’s a good yarn. It riffs on the astrology theme in a way that I’ve personally not encountered in sci-fi (astrology is still annoying, don’t @ me!). It’s a great example of the art form, bringing graphics, music and writing together into a coherent whole. I would enjoy reading about the further adventures of Lana Brice, and will definitely pay attention to ImpQueen’s future works.

Liberapay allows to make recurrent donations to projects and people working on libre projects. It’s non-profit so the only cuts taken are the actual payment fees. You can support Liberapay itself by donating to it’s team within the service.

The site is easy to use and well made. There are good tools for managing your donations. It’s also easy to discover new interesting projects on the platform. I bet you will find there software you’re already using!

The Great Ace Attorney Adventures is the first game in a spin-off series from the modern classic Ace Attorney series of games built around criminal cases and court drama.

It differs mainly in that, as opposed to the rest of the series, it isn’t set in contemporary times, but during the late 19th century in Meiji period Japan and the British Empire.

You take on the role of Japanese Student Ryunosuke Naruhodo, who, after successfully battling himself out of the court for a crime he didn’t commit, goes abroad to the British Empire to study the British law and judicial system. Ryunosuke isn’t a law student, so this doubles as his journey of becoming a lawyer.

What the spin-off affords the game

The spin-off affords many exciting opportunities, but, of course, also challenges.

The game essentially being a clean slate allows for a sharp departure from the established series canon. The completely new cast of characters is the most obvious example.

Another such example is the soundtrack. Prior games in the series heavily relied on previously established melodies and themes. Those were usually either reused directly from previous games or arranged for jumping from one console generation to the next. The Great Ace Attorney features a completely original and orchestrated soundtrack. It sounds great, and it fits the period the game is depicting. But in my opinion, much more importantly, it helps the game establish an identity of its own.

The historical setting has also been used in a few compelling ways. So far, the series hadn’t made historical references at all. This was further complicated by the English localisation of the series changing the setting from Japan to the USA. Now, however, the game is brimming with historical references and factoids about late 19th century Japan and England. The game references laws from the time, local buildings in England such as the Old Bailey court, and famous historical figures like the Japanese author Sōseki Natsume.

New faces, old faces

While the game features a compelling original cast of characters, they largely fall into familiar archetypes.

The protagonist, Ryunosuke Naruhodo, comes very naturally after Phoenix Wright from the main series. He is determined and brave but also despairs easily in stressful situations in the courtroom. In Ryunosuke’s case, though, that character flaw is more understandable since he never studied to become a lawyer.

Susato Mikotoba is Ryunosuke’s judicial assistant. She clearly comes after Maya Fey from the main series, though not as playful. The charming, witty and empathetic character will be familiar to anyone who has played the original trilogy. On top of that, she is also quite assertive and forceful at times. I like her a lot, but I cannot help but see the missed opportunity for a female lead character here. The main series attempted to bring a female character to the cast of protagonists, but this was, for the most part, isolated to one case and neglected in the following release.

This game provided a clean slate, so the trouble of having to integrate a new character into a cast of well-known ones would have been avoided. And if you would have me believe that the British state would permit a foreigner with no formal education to work as a lawyer, why not a woman?

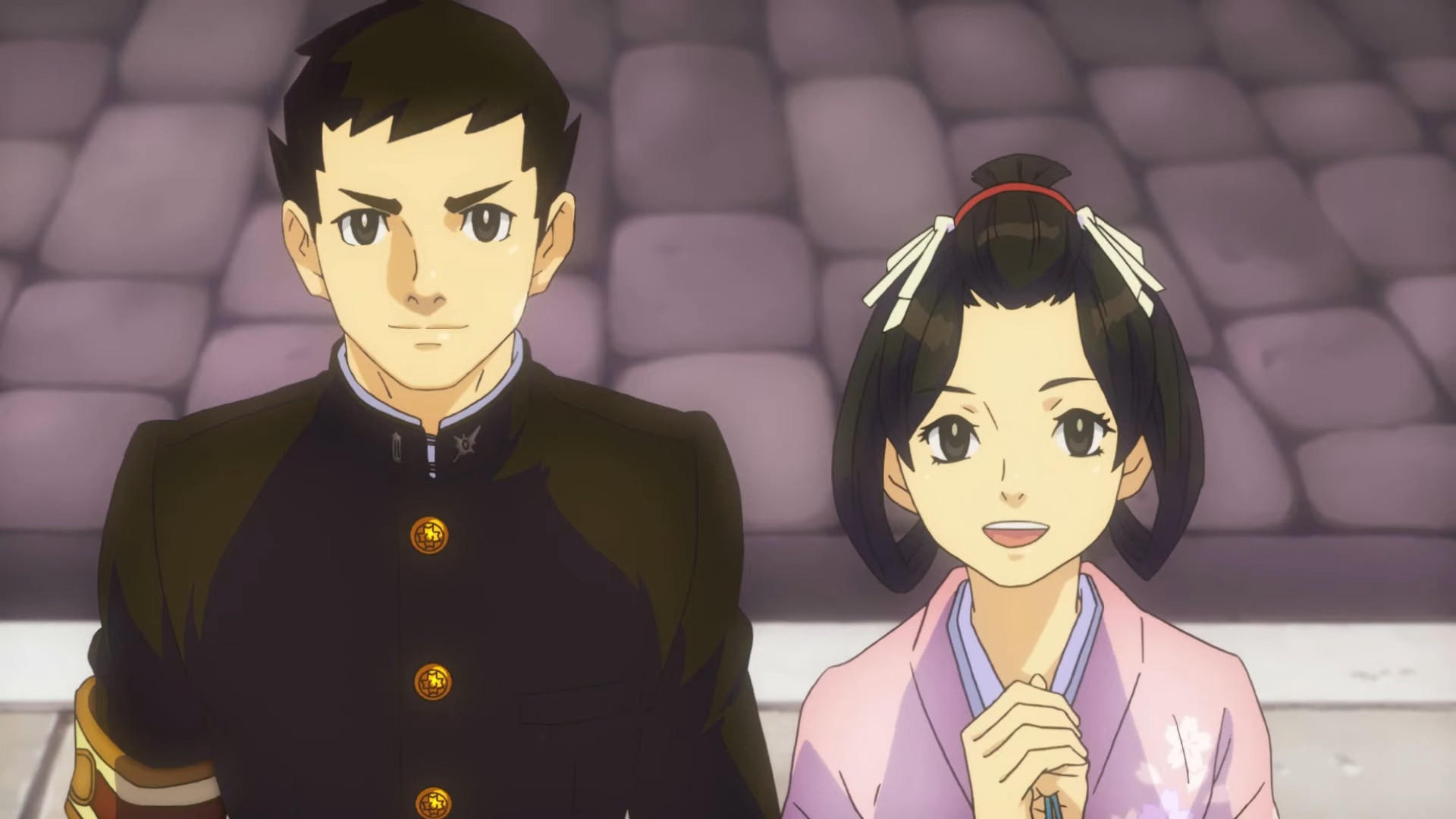

Our new pair of protagonists. (Credit: Capcom. Fair use.)

Two characters that defy previous archetypes in the series are Herlock Sholmes (yes, you read that correctly) and Iris Wilson. With a game set in Victorian London, the Sherlock Holmes character is a must, of course. Herlock is the same unstable genius we know from many stories in his young years. However, his deduction skills are not as good as the popular stories usually depict. He frequently gets small details wrong, and you’ll have a fun time correcting those mistakes. This twist is nice and, clearly, Sholmes is supposed to be one of the stars of the game, but I find the character of his assistant, Iris Wilson, much more interesting.

Iris Wilson is far more than just a gender swap for Dr Watson. She is a child prodigy, inventor, and chronicler of Sholmes’ adventures. At just ten years of age, Sholmes acts as her adoptive father of sorts, but she comes across as much more mature than him. She is charming and intelligent, and I’m sad we only see so little of her in this game.

As opposed to Herlock, who is a synthesis of the many different renditions the character has seen in fiction, Iris is almost completely original. Sholmes is what you would expect, but the only thing of Watson that remains in Wilson is that she is the chronicler of his adventures and that they live together.

The final character that sticks out is the series-typical prosecutor: Lord van Zieks. He is pale and dressed like an English aristocrat. This makes him look like a vampire and the game heavily leans into that. He absorbs the entire courtroom with his assertive personality every time it’s his turn to speak. His theme that prominently features a harpsichord and hits you like a brick wall of sound really sells those moments.

Van Zieks is very fun to watch. He often plays around with a wine glass of his: filling it, drinking from it, tossing it, or crushing it—I certainly appreciate the Castlevania references. He makes for a top contender for Top Prosecutor in the series, and that’s a title with tough competition.

Overall I’m happy with these new characters, but also a bit sad that largely the game falls back on established tropes instead of trying new things like with Sholmes and Wilson. This instance of a spin-off would have been the perfect moment to do it.

Old themes extended and revised

The Great Ace Attorney Adventures doesn’t waste this opportunity of a new beginning by just continuing the themes of the series and leaving it at that. Entirely new thematic strands are being explored here.

For one, the series, thus far, explored several issues in the legal system, often in the hyperbolic way. We are to understand that the justice system is not just at all. It is never explained, however, how it came to be that way. That is where this game comes in.

The Great Ace Attorney Adventures explores how the Japanese legal system was formed during the Meiji period of liberalisation and how it was greatly inspired by the legal system of the British Empire. When Ryunosuke goes abroad to London, we see many of the same issues already present. It’s very interesting to see this unfold, and it gives this game the fresh coating you would expect from a spin-off.

Certain aspects of the British Empire are greatly emphasised, even caricatured at times, to deliver an image of Britain that reflects Japanese views of it at the time. One such heavily emphasised thing is the technological superiority of the British Empire. The Japanese Empire, in its pursuit of liberalisation, sought to partially imitate the British Empire. As such, Japan is seen as technologically unadvanced, and one looks with marvel at the technological achievements of the British.

When our protagonists arrive in London, they speak at lengths about how different and greater everything is. The first interaction with the British legal system leads them to the office of the Lord Chief Justice, where a huge mechanical construct of gears looms in the background. While that is architecturally impractical and would make for a terrible place to do office work in, it drives home the message the game is trying to convey very efficiently.

The game does not solely portray British society as superior it also makes it clear that they see themselves that way. This leads to broaching the issue of the open white supremacy of Europe at the time. There are a lot of instances where racial prejudice is directed at the Japanese characters in this game. While certainly unpleasant, it obviously has its place in a game making historical commentary. But I can’t say that I care much about this aspect. It boils down to the Japanese characters taking the racist abuse and later proving the person making racist remarks wrong. This happens by showing their competency, or that they possess a positive character trait that contradicts the stereotype. I really dislike this because would the racism have been fine if the racist stereotype was confirmed in that instance? It makes for shallow commentary, that’s it.

Beyond that, another interesting component of the game is the jury. A group of six London citizens, chosen at random to decide the verdict. The game portrays these people as impulsive and easily swayed, effectively showing that involvement of the public like this doesn’t make for a better justice system.

This is interesting because in Apollo Justice: Ace Attorney, the “Jurist System” is presented as the solution to the game’s final conflict. This is not necessarily a contradiction, even though it might appear at first that the expressed opinions have changed here. The series often times shows your protagonists subverting, or outright breaking the law to peruse legal justice in this series. Clearly, that wouldn’t make for a great legal system. And yet these actions are shown as essential to deliver justice. The way this looks to me is that the game is saying that no justice system is capable of delivering justice in all cases. It might have previously looked like advocacy for a jury system, but this game clearly rejects that.

The game also continues the theme of belief in the justice system being like a religion. The Old Bailey courtroom looks very similar to the insides of a church with its stained glass windows. That house never had windows like that, but one would be missing the point if one were to criticise the game for not being historically accurate. In Gyakuten Kenji 2, the windows of the high prosecutorial office were styled similarly. Clearly, the game is connecting itself with this broader established theme. Though that connection is much thinner than in previous titles. Gyakuten Kenji 2 features the topic much more prominently, and Ace Attorney: Spirit of Justice, released one year after this one, made it the entire premise of the game, so I am not complaining.

There are other moments in the game that felt like they were commenting on previous titles in the series. Most noticeably, when the game makes you defend a guilty person, similarly to Justice for All. Except here, it isn’t the big revelation at the end of the game, but instead, it is used to build a story of betrayal and trust. The game gives you a case that violates your trust, and in a later case builds that trust back up again.

The big difference between the two clients used to tell the story is wealth. While your wealthy client uses you as a pawn to cheat the system, the other person is poor and has no one to put their faith into. The game’s message is clear: it is the poor people that need your help in this system, not the wealthy. I like this because it is much more in line with the identity the games developed over the years and ask much more interesting moral questions than: “But what if you defend a murderer?”

The gameplay additions

By now it should be clear, how this spin-off does take some new directions, but mostly tries to stay faithful to the core of the series. The gameplay is no different.

Largely the game follows the same gameplay tropes as the rest of the series and the additional court room mechanics from Professor Layton vs. Phoenix Wright: Ace Attorney. This means multiple people can and almost always will testify simultaneously. Along with that, there are “Pursuits”, which are essentially ways of furthering the cross-examination by pressing other witnesses on the bench for their thoughts on the current statement. I’m happy these are back and are allowed to shine in a proper Ace Attorney game and not just a crossover.

A new addition to courtroom sections comes with the jury. When the jury unanimously advocates for a guilty verdict, you get the chance to examine the jury’s grounds for doing so. These jury examinations function similarly to cross-examinations. Each juror presents their reasoning as a statemented. But unlike cross-examinations, your goal isn’t to uncover a lie, but to change the juror’s mind to prolong the trial. You do this by pitting contradictory statements by two jurors against each other.

The jury examinations introduce a new dynamic into the court room, because the way you would usually progress in such a section is by presenting evidence, but here it exclusively works with the statements themselves. This isn’t entirely new, though. In a previous game, there was an instance of having to press statements during a cross-examination multiple times in a specific order, to uncover the underlying contradiction. This didn’t work well however, because up until that point, you only ever had to press statements once.

Now, this idea was given its own feature and works much better that way. It makes for a welcome change of pace during court sections and you get to see more action from your main character, instead of a constant back-and-forth with the prosecution.

The other big feature that was added to exploration and examination sections are moments of so-called “Joint Reasoning”, where Ryunosuke joins intellectual forces with Sholmes. The detective may be world famous for his deduction skills, but in reality he often times gets crucial details wrong, even though his intuition leads him mostly on the right path. That’s where you as Ryunosuke come in. You get to identify and correct the small details Sholmes got wrong, to produce a properly useful deduction. This, again, is a bit like cross-examinations. You stop at a statement made by Sholmes and then try to figure out what he got wrong and present your own version of his statement. This usually involves looking around the environment for clues or presenting evidence from the court record.

All of this is presented in a very flashy and lively way. It almost feels alien to see characters move around so much on screen. Here the series is truly reaping the benefits transitioning to 3D.

It’s fun to watch, though the setup for it is bit longer than it needs to be in my opinion. But beyond that, it introduces some of the drama of the court room into the more calm exploration sections, which, just like the jury examinations, makes for a nice change of pace.

Sharply uphill, with rough decline

So far, I’ve been almost exclusively positive about this game. I really want to impress on you, how many good things this game has going for it. Other games in the series achieved great things with less. It is then a huge disappointment that a lot of this potential remains unused.

All of the great things I talked about so far get completely overshadows by the game’s poor pacing and structure. I will say, the game has a strong start, arguably the best in the entire series. Ryunosuke having to defend himself as a layperson in a case of high national interest immediately puts the stakes high. In the next case you get some breathing room with a pure investigation case. The game cleverly uses that time to introduce Sholmes and for you to learn about your soon to be judicial assistant, Susato.

It’s also a good setup for the next case which for balance, you’ll be spending entirely in court. Here the game also does a lot. It has to introduce the unique elements of the British justice system and introduce you to several new characters, including the new prosecutor van Zieks. At the same time, it’s the one chance Ryunosuke gets to prove his competency as an untrained lawyer. And further, the game makes you slowly realise that your client is a monster, who has deceived you into helping him in his scheme to cheat the justice system.

This makes for the climax of the game. It feels great up until that point, but after this there are two more cases. The one that follows is a lot slower, so you can recover from what came before. And the final case attempts to be the finale of the game, like is tradition for Ace Attorney. I say “attempt”, because it employs all the usual tropes to signal that the stakes are high, and even hints at the possibility of a conspiracy within the police. But all of this on reveal deflates to nothing. I cannot express just how disappointing that is.

I am not opposed to the third case being the high point of the game. It would be perfectly fine for this game and its sequel The Great Ace Attorney Resolve to play like one big game split into two, with the latter half of the first game properly preparing you for what will come in the second game.

To some extent, the game does do this. For example, it introduces you to Iris Wilson who no doubt, will have a huge role to play in the sequel, but then the game gets trapped in trying to deliver the typical Ace Attorney experience with a huge final case. But what is there just doesn’t live up to it.

In the end, there is a lot of hasty setup for a sequel, which leaves a sour taste in my mouth. It feels like the game saying that in the sequel, maybe, there is going to be an actually satisfying conclusion. All of this could have been avoided by not setting the expectations like that.

I am sure, that in that case, I would have finished this game much more satisfied.

Conclusion

The Great Ace Attorney Adventures has a lot of very interesting aspects to it. But unfortunately a lot of that potential is squandered by the game’s pacing and structure, which is terrible for a game that is part Adventure, part Visual Novel.

The first half of the game remains very good, even after finishing on a sour note. It makes you yearn for this game with the pacing issues absent.

Overall I can’t say this game is all that worth playing on its own. Especially not when there are so many other great games to choose from in this series. I hope that with all the build-up for the sequel, it turns out better than this game.

6/10