Latest reviews

Pumpkin Eater is a kinetic visual novel, which means that it’s a story with art and sound, but with no player choices. The $2 regular sales price suggests a short story, and indeed I finished it in about 30 minutes.

Given how short it is, I don’t want to give too much away. In a nutshell, it’s about a family who loses a child in an accident but cannot let go. What follows is a tale of decay and insanity, told in (the authors assert) a medically accurate manner.

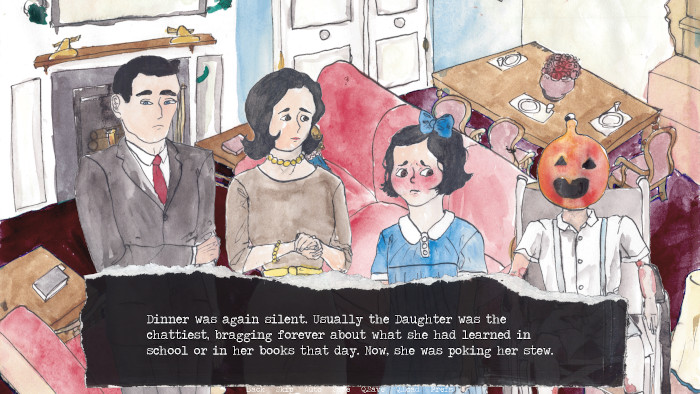

The characters and backgrounds are lovingly painted in watercolor, which creates a contrast with the story’s morbid content. (Credit: thugzilladev. Fair use.)

I appreciate attempts to demystify death, even if it’s done in the form of a horror story. Ultimately, that seems to the point of the game, which comes complete with a glossary.

The story is engaging, and it uses music and sound effects well. It won’t scare your pants off, but it might make you lose your appetite. It is also likely to stay with you. 3.5 stars, rounded up.

When governments, corporations and other organizations act unethically or illegally, only people on the inside may know about it. If they choose to tell someone who might bring about change, they become whistleblowers.

Published in 2001, C. Fred Alford’s Whistleblowers: Broken Lives and Organizational Power examines the personal sacrifice it takes to oppose an organization’s actions. From interviews and a review of prior research, Alford concludes that in spite of many legislative attempts to protect whistleblowers, retaliation is the norm, not the exception.

How organizations fight back

Whistleblowers are often not fired immediately. They are moved to “offices” that previously served as closets; their responsibilities are curtailed; their performance is put under a microscope. Only after sufficient time has passed to create distance to the act of whistleblowing, they are fired, frequently for “poor performance”.

After losing their job, they may find it impossible to work in their chosen sector again, thanks to informal blacklists. Whistleblowers are portrayed as “nuts and sluts”, their sanity and character called into question. As Alford puts it, the process is complete “when a fifty-five-year-old engineer delivers pizza to pay the rent on a two-room walkup.”

Considering this characterization, one might expect Alford to support whistleblower anonymity. Not so—anonymity, he claims, is a road to nowhere (p. 36):

Anonymous whistleblowing happens when ethical discourse becomes impossible, when acting ethically is tantamount to becoming a scapegoat. It is an instrumental solution to a discursive problem, the problem of not being able to talk about what we are doing. Whistleblowing without whistleblowers is not a future we should aspire to, any more than individuality without individuals or citizenship without citizens. If everyone has to hide in order to say anything of ethical consequence (as opposed to “mere” political opinion), then we will all end our days as drivers on a vast freeway: darkened windshields, darkened license plate holders, dark glasses, speeding aggressively to God knows where.

Personally, I think an “instrumental solution to a discursive problem” is still a fine solution, especially if it happens to save lives or serve the public interest. Much as Alford agonizes about the sacrifices whistleblowers make, he seems unwilling to imagine a world in which those sacrifices can be lessened.

Psychoanalysis to the rescue

Because many of the people Alford spoke with attended self-help groups (which selects for trauma), and because his book rarely deals in numbers, it’s difficult to say how statistically valid his observations are. Much of the book is focused on psychoanalysis: What causes whistleblowers to act, and how do they process the consequences of their actions?

Alford theorizes that whistleblowers are motivated by what he describes as “narcissism moralized”. To put it another way, whistleblowers can tolerate the alienation from everyone else more than they can tolerate being in conflict with their idealized moral self.

It’s a reasonable argument, considering that whistleblowers often act alone—so their impulse to act is often likely the result of an inner conflict. But when he characterizes whistleblowers’ motives and feelings, Alford readily dismisses evidence that isn’t consistent with his own views.

In describing one case, he writes: “Ted protests too much. For that reason I distrust his account” (p. 39). This kind of reasoning makes me worried that the author may be an unreliable narrator of whistleblower motivations, and I would rather read more quotes and fewer abstract characterizations.

How many whistleblowers discuss their actions with loved ones beforehand? How many are deeply appalled by imagining the consequences of the organization’s actions on the outside world? What Alford offers us are generalizations, made more tedious with frequent repetition and verbosity, for example, when he writes about the state of “thoughtlessness” (p. 121):

Thoughtlessness stems not merely, or even primarily, from fear. Thoughtlessness arises when we are unable to explain our fears—that is, make them meaningful, comprehensible, knowable. This happens when we lack the categories to bring our fears into being. Common narrative is, I’ve argued, of little help in this regard.

Social theory could be more helpful than it is. Liberal democratic theory assumes that politics is where the action is, and so it assumes that individualism is possible. Foucault’s account assumes that individuals don’t exist. Neither approach gets close enough to life in the organization, to say nothing of the lives of those who suffer the organization, to help individuals make sense of the forces arrayed against them.

If you enjoy the kind of analysis that says in 100 words what could be said in 10, you’ll find plenty of it here.

The Verdict

In fairness, Whistleblowers is a short book (170 pages including the index), and it does tell some interesting stories about different types of whistleblowers in different fields, from engineering to accounting.

It offers some metaphors which I’ll almost certainly find myself using again—for example, it describes life after whistleblowing as akin to space-walking, because many whistleblowers have learned the hard way that the world doesn’t work the way they thought it did.

The most useful takeaway from Alford’s book is a deeper understanding of the often very heavy cost of whistleblowing. Alford ultimately characterizes it as a “sacred” act; I would compare it perhaps with blasphemy. To understand the cost of telling the truth should prepare us to lessen it.

Gabriel ist jung Vater geworden und lebt mit seinem Sohn Jamie. Er ist in einer Clique von Skatern. Gabriel hat ein Samurai-Schwert und, ähnlich wie im Film “Ghost Dog”, werden Samuraisprüche während des Films erzählt. Gabriel lernt Corry, die Freundin seines Freundes Joel, kennen. Corry, Joel und Gabriel nehmen Drogen, steigen im Rausch in den Züricher Zoo ein und lassen zwei Pumas und eine Giraffe frei. Jamies Mutter Mutter ist Fernsehsprecherin und berichtet über die freigelassenen Tiere. Gabriel und Jamie gehen auch einmal zum Haus der Fernsehsprecherin um Jamie’s Mutter Zoé zu besuchen. Es ist gerade Party dort, und dem Mädchen ist schwindlig. Ein paar Tote und Verletzte später endet der Film.

Soul of a Beast ist ein etwas schwieriger Film. Es sind sehr viele Elemente hineingemischt, egal ob Szenerie, Situationen, Stilmittel, verschiedene Kulturen wie Asien, Europa, Afrika, Südamerika, Natur, Stadt, real, unter Drogen, Friede, Militär, Polizei. Es wirkt ein bisschen als wäre es der letzte Film den Lorenz Merz in seinem Leben machen könnte und alles enthalten sein muss. Die 100 Minuten reichen bei weitem nicht aus um diese Elemente vernünftig zu entfalten. Ausser die Dialoge - die sind sehr kurz. Zu kurz vielleicht. Ausser von der Grossmutter erfährt man kaum etwas von den handelnden Personen, sie kommen und gehen. Viele Szenen sind irgendwie dunkel, blutverschmiert, meist voller Müll. Die Umgebung wirkt immer überladen, überzeichnet. Gabriels Auto ist voll, Gabriels Wohnung ist voll, Zoé’s Mutter hat viele Bedienstete. Im Wald ist es nur grün, völlig unmotiviert steht auf einmal ein einzelner gut getarnter Soldat auf, der Zürisee ist schön. Am Ende bleiben Fragen über Fragen, es bleibt das dumpfe Gefühl dass irgendwas fehlt.

Cyberpunk stories often take place on Earth in a dystopian future characterized by a) darkness, rain and neon lights, b) corporations running everything. So, really, mostly a darker, rainier version of the present.

Synergia, a visual novel by indie developer Radi Art, takes place on a desert planet colonized by humans that is home to multiple political factions, including a dominant superpower, the Empire.

In other respects, it follows the cyberpunk template, featuring cityscapes drenched in neon lights; cyborgs, androids, and evil corporations. It also takes itself quite seriously.

This is a mostly kinetic visual novel, meaning that there are only a few choices (three in total) you get to make to influence the course of the 4-5 hour long story.

The story revolves around Escila, or Cila for short, a cop demoted under circumstances that will be revealed later in the story. When looking to replace her household android, she gets more than she bargained for: an outgoing, cheerful and remarkably human-like android named Mara. Cila soon becomes entangled in a web of conspiracy and romance.

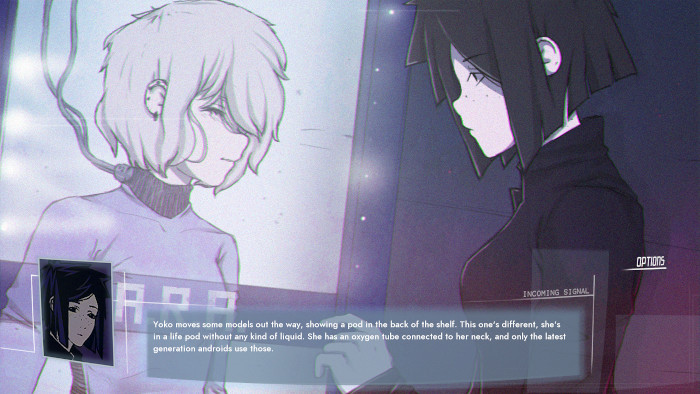

Some of the full-screen art is quite well-done. Here, Cila encounters the android Mara for the first time. (Credit: Radi Art. Fair use.)

Romance without chemistry

Synergia is at its heart about the relationship between Cila and Mara. Unfortunately, as a romance story, Synergia failed to click for me. It reads as a relationship of necessity and convenience—two people drawn together only out of alienation towards the rest of the world, and out of sheer loneliness.

The larger narrative of a conspiracy involving androids, rebels, and corporations is convoluted and unsatisfying. Dialogue doesn’t read like the interaction between different people, but like a single writer cramming exposition into speech bubbles. It doesn’t help that the UI doesn’t always make it obvious who’s talking.

The writing suffers from a few typos and grammar errors. The character art and backgrounds are original and maintain a coherent style. As is typical for low budget visual novels, a few backgrounds are overused. The game’s strongest point is its soundtrack, which never dominates but creates suitable ambience.

I can’t recommend Synergia, but your mileage may vary. If you love the cyberpunk aesthetic and enjoy romance stories that are on the more mechanical side, you may get something out of it.

Ho mangiato benissimo, i piatti erano abbondanti e ad un prezzo contenuto. Ci sono capitato per caso durante un sabato a pranzo e ho apprezzato tanto sia il servizio, sia il cibo veramente ottimo e fresco.

Il menù si trova sul sito internet ed è contenuto il giusto che basta per darti una selezione variegata di piatti senza farti spulciare ingredienti e varie all’infinito.

Slay the Spire is not the first roguelike deck-building game, but its massive success created a recipe many indie developers would soon try to follow.

The game doesn’t owe its popularity to its rich lore. You’re ascending a tower—excuse me, spire—fighting monsters on its many floors, to face a final enemy: a corrupted, beating heart. Random events hint at a larger mythology, but if you’re looking for a narrative adventure, look elsewhere.

The monster bestiary is also not what will keep you playing this game. While the art and animation are always serviceable, the array of cloaked figures, slimes, geometric shapes, and bands of thieves and gremlins gets a bit samey after a while.

What sets Slay the Spire apart is the tightness of the card-based battle mechanics, the unique play styles of the different characters, and the clever combination of cards and relics to make each run feel different.

Chance and strategy

You first play as the “Ironclad”, a powerful masked warrior. You navigate the spire across a path of your choice: you can face challenging encounters with large rewards, pursue random events, or plot the safest course to the level boss.

Monsters on the map indicate turn-based battles against one or multiple opponents. You draw cards from your deck in random order, and expend limited energy to play some of them. (Your opponents don’t have cards.)

The game will usually tell you what the enemy will do next: attack, defend, inflict status effects, and so on. This gives you a chance to prepare: if the enemy is about to do a lot of damage, you better have those defenses ready.

After each battle, you pick up new cards and other loot. As you ascend the spire, you’ll also find treasure chests and shops. Question marks on the map lead to random events. Those may have small negative or positive consequences, or give you dramatic choices: Would you like to play the rest of the game as a vampire?

The Silent, one of the four playable characters, faces a Shelled Parasite. It will take carefully planned moves to penetrate the monster’s plated armor while minimizing inbound damage. (Credit: MegaCrit. Fair use.)

Game-changers

Among the items you can find are relics. These can significantly alter the game mechanics—for example, you might get extra energy every three turns, or boost the effectiveness of certain cards.

More and more content gets unlocked the longer you play—additional characters (four in total), cards, and relics. That means that a relic you unlock after 20 hours of play could be transformative for your next run.

The four characters offer fundamentally different play styles: The Silent is a rogue whose cumulative poison attacks can bring down the most powerful foe. The Defects is a sentient automaton who uses orbiting energy orbs to line up deadly chain reactions. The Watcher is a blind ascetic who uses “stances” to collect her energy and defenses (“calm”), then attack with twice the strength and vulnerability at the right moment (“wrath”).

Learning by dying

Battles can feel terribly unfair—such is the nature of roguelikes—but there’s enough strategic depth to reward repeated play. You will get better, learn to avoid unnecessary risks, and achieve easy defeats in battles that seemed unwinnable before.

To keep you playing, the game never ceases to throw new challenges your way, and that’s without taking into account lovingly created mods like Downfall, a fan expansion that lets you play as the bosses.

After 40 hours of play, having faced (but not defeated) the game’s ultimate boss and unlocked most cards and items, I’ve decided to put Slay the Spire down again for now. But I know it’s sitting in my library, ready to give that dopamine rush that only a perfectly executed game can.

If you like the genre, I also recommend Krumit’s Tale (review), Iris and the Giant (review), and Dicey Dungeons (review). All were released after Slay the Spire, and each brings something new to the genre.

The main focus of Hardcore Gaming 101’s “Retro Indie Games” book series are games that look, feel and/or play like old-school games from the 1980s and 1990s, but that are much more recent indie titles. (See my review of the first volume.)

The second volume covers both old titles that didn’t make the cut last time (e.g., Papers, Please! and Fez), and very recent games like Helltaker, Paradise Killer and Lair of the Clockwork God.

The format is largely the same as before: each game is richly illustrated and described in detail, with heavy focus on gameplay and story, and little emphasis on any other aspect such as the developers or how the game was made. As before, games are grouped by developer.

With 67 individual games, every reader with any appreciation for indie games is likely to discover at least one or two to add to their backlog. For me, that included Katana Zero (the time manipulation mechanic sounds super-interesting) and The Binding of Isaac (it just seems like a wild ride).

As with the first volume, I still feel the series could do better at being an actual guide to genres and developers. As an effort to catalog and describe some of the greatest retro-styled indie titles of the last decade or so, it is without equal.

The full list of games in the second volume follows (grouped by developer):

Cuphead

Celeste

Panzer Paladin

The Messenger

Cyber Shadow

Gunpoint

Aces Wild

Blazing Chrome

Katana Zero

Minit

Fight ‘n Rage

198X

Cave Story

Kero Blaster

La-Mulana (series)

Xeodrifter

Hollow Knight

Blasphemous

Iconoclasts

Dex

Rabi-Ribi

Pharaoh Rebirth

Touhou Luna Nights

Record of Lodoss War: Deedlit in Wonder Labyrinth

Fez

The Binding of Isaac

Dusk

Project Warlock

AMID EVIL

Cruelty Squad

Saturday Morning RPG

Cosmic Star Heroine

Anodyne

Anodyne 2: Return to Dust

Into the Breach

Chroma Squad

Katawa Shoujo

Digital: A Love Story

Don’t take it personally babe, it’s just not your story

Analogue: A Hate Story/Hate Plus

Ladykiller in a Bind

Broken Reality

Coffee Talk

Unavowed

Lamplight City

The Low Road

Ben There, Dan That!

Time Gentlemen, Please!

Lair of the Clockwork God

Paradise Killer

Return of the Obra Dinn

Umurangi Generation

Hypnospace Outlaw

Oxenfree

Back in 1995

Stories Untold

The Count Lucanor

Yuppie Psycho

Detention

Devotion

Paratopic

Anatomy

Papers, Please

Stardew Valley

Helltaker

As a twelve-year-old, Gwendy Peterson met a stranger who gave her a magical box that can destroy the world. That’s the premise of the Gwendy trilogy by Stephen King and Richard Chizmar.

The first book, Gwendy’s Button Box (review), was a fine story that stood on its own as a morality tale. The titular button box can fulfill wishes and wreak destruction—including at the planetary scale. As child custodian of the box, Gwendy used some of its powers, but was never corrupted by them.

In the mediocre sequel, Gwendy’s Magic Feather (review), Gwendy became a celebrated author and elected Congresswoman, and the box once more played an (ultimately anticlimactic) role in her life.

In Gwendy’s Final Task, the mysterious man or being who originally gave her the box tasks her to get rid of it once and for all. Because it’s a magical box, throwing it into a volcano won’t do. It must be…shot into space!

And so it is that Gwendy, now a Senator, finds herself on the way to a space station, with the button box locked away in a steel box marked “CLASSIFIED MATERIAL”. The spaceflight is organized by a SpaceX-style private company that is hoping to monetize space tourism.

That explains why one of the other passengers on board is an obnoxious billionaire. It doesn’t explain why the man seems to be completely obsessed by what’s in the steel box. Meanwhile, Gwendy is literally losing her mind to early onset Alzheimer’s disease.

The setup is ridiculous, but it mostly works. The enclosed environment, combined with Gwendy’s dwindling mental faculties, builds suspense. King rewards his constant readers with plenty of references to other works, including the Dark Tower series many consider his magnum opus.

The ending leaves no doubt that this truly is the final book in the series. That’s probably for the best. If you’ve made it to the second book, the conclusion is definitely an improvement, and I would recommend picking it up. If you’ve not started the trilogy yet, there are much better works in King’s oeuvre.

In the late 19th century, as the United States fully consolidated itself and its territory (through war and ethnic cleansing), its elites began to realize openly imperial ambitions. These ambitions reached a fever pitch in the Spanish-American War, which led to the US establishing control over Puerto Rico, the Philippines, Guam, and (nominally independent) Cuba.

When Smedley Butler, the son of an influential Pennsylvania family, joined the US Marines in 1898, he was caught up in the war fever of the time. But instead of fighting the Spanish, he soon found himself helping to police America’s empire on behalf of its most powerful economic interests.

Decades later, Butler, now a Major General, started to write his own script. In 1933, he alleged that he was invited to take part in a conspiracy among wealthy businessmen to overthrow U.S. President Roosevelt and install a dictator.

It became known as the Business Plot. A congressional committee concluded that “there is no question that these attempts were discussed, were planned, and might have been placed in execution when and if the financial backers deemed it expedient." Nobody was prosecuted.

In his final years, an increasingly radical Butler gave fiery speeches and penned a short book called War is a Racket. It contains the following passage:

I helped make Mexico, especially Tampico, safe for American oil interests in 1914. I helped make Haiti and Cuba a decent place for the National City Bank boys to collect revenues in. I helped in the raping of half a dozen Central American republics for the benefits of Wall Street.

Late in his life, Butler denounced war and empire, and fought for veterans’ rights. (Credit: Bettman/Getty Images. Fair use.)

Legacies of Empire

For American journalist Jonathan Katz, Butler’s life presents a lens through which to view the history of American imperialism, and its modern legacies. In Gangster of Capitalism, Katz traces Butler’s career in the military and his stint as Philadelphia’s “Director of Public Safety”, a role in which he waged a brutal war on crime in the city.

Katz makes it clear that Butler, in spite of his Quaker upbringing, committed truly horrific and violent actions, and often rationalized them through the pervasive racism of the time. As part of the nearly 20-year-long occupation of Haiti by the United States, Butler instituted de facto slavery to build up the country’s infrastructure.

Unlike the opaque Business Plot, the corporate interests that profited from these endeavors and drove US policies are well-documented, from bankers to landowners to oil companies. Franklin Roosevelt himself pursued personal agriculture investments in Haiti while helping direct its occupation as Assistant Secretary of the Navy.

In each chapter, Katz describes the modern legacy of American imperialism, including by quoting Haitians, Filipinos, Chinese, and others he has met. While Americans have forgotten the little they have ever known of this history, the citizens of these countries have not. Katz’s travelogue enriches the book and makes this history tangible.

Past and Prologue

Gangsters of Capitalism is an accessible, informative and engaging book. At no point does Katz turn from facts to polemic. He gives clear-eyed accounts of the brutal regime of Nicaragua’s leftist autocrat Daniel Ortega, and the imperialist ideology of China under Xi Jinping. The book is a critique of empire, not an anti-American screed.

It is also a timely book, as another imperialist power, Russia, wages a war of aggression against neighboring Ukraine. What role should Western powers play today to counter such naked brutality? Can military alliances like NATO protect the peace in the 21st century? What alternatives are there?

The invasion of Ukraine marks a new chapter in world history, and we all benefit from remembering previous chapters—including America’s own brutal imperial history—to navigate the moral landscape now before us.

Dexter war vor Jahren eine meiner Lieblingsserien und das ging bestimmt nicht nur mir so. Innerhalb der ersten vier Staffeln wurde die Handlung um den Serienmörder in Diensten der Polizei spannend und gut inszeniert herübergebracht. Die weiteren vier Staffeln kamen nicht mehr an das Niveau der anderen heran aber trotzdem bleib ich dabei um zu erfahren wie es weitergeht. Und am Ende der achten Staffel war für mich klar, das es nicht mehr weitergehen kann. Der Abgang Dexters hat für mein Empfinden keinen Spielraum für eine Rückkehr gegeben. Tja, was soll ich sagen? Ich habe mich getäuscht.

Die Geschichte startet in einer US-amerikanischen Kleinstadt und ich war von Anfang an wieder im Dexter-Fieber. Vergessen war das seltsame Ende der achten Staffel. Die Stimmung im winterlichen Handlungsort ist gut eingefangen und wird rund um den Hauptdarsteller gut aufgebaut. Auch wenn in der ersten Folge für Neulinge nicht ganz klar wird, was hier eigentlich los ist. Diese Folge wird meiner Meinung nach nur zur Schaffung der Atmosphäre verwendet. So kommen auch Leute, die bisher keinen Kontakt mit Dexter Morgan hatten, in die Dexter-Stimmung.

Anfangs ist unklar wer welche Rolle hat. Wer ist der Böse, wer nicht und wann kommt es zur ersten Dexter-typischen Handlung. Der Reiz und die gut eingefangene Atmosphäre haben mich die komplette Staffel in drei Tagen durchschauen lassen und es war zu keinem Zeitpunkt langweilig. Die Spannung wird gut aufgebaut und es wird langsam aber sicher klar wer welche Rolle spielt und welches Schicksal diese Personen erleiden werden.

Warnung: Der untenstehende Text enthält Spoiler.

Diesmal wird es leider endgültig keine Fortsetzung geben. Aus dem für mich nicht hervorsehbaren Ende kommt selbst Dexter nicht mehr heraus. Aber wer weiß ob sein Sprössling nicht den selben Weg einschlägt und wir in ein paar Jahren eine weitere Staffel zu sehen bekommen. Wir werden es sehen.